INTRODUCTION

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is a non-homogeneous form of oral leukoplakia (OL). It is characterized by multifocal, slow-growing white plaques that are refractory to therapeutic procedures and have high rates of recurrence and malignancy (1-3) ranging from 70 to 100% of all cases (4-7).

In the early stages, it may present clinicopathological aspects similar to oral lichen planus (OLP) (3,8) which is an immunologically mediated mucocutaneous disease with a malignant transformation rate of approximately 1.4% (9). Clinically, both can present as multifocal white plaques or striae, bilaterally affecting the buccal mucosa and the alveolar ridge, attached gingiva, tongue, and lips (10,11). The verrucous conformation formed by surface keratin is an important clinical finding that contributes to the distinction between PVL and OLP (12-14). Both affect predominantly women in their 60s who do not use tobacco or alcohol (15,16). Given the overlapping clinical and epidemiological characteristics of PVL and OLP, relying solely on these factors for diagnosis is insufficient. Therefore, microscopic evaluation becomes imperative (11,17).

Microscopic findings of OLP can closely resemble those observed in PVL, but PVL can present dysplasia ranging from mild to severe, or, in some instances, reveal a squamous cell carcinoma (5). However, PVL lacks uniformity, thus tissues from the same patient and different anatomical locations may differ from each other (12,18). Areas affected by PVL might exhibit a banded lymphocytic infiltrate, and by combining the clinical and microscopic features, a misdiagnosis of OLP may be established, especially in early cases where there is no epithelial dysplasia (13,18-20).

This report presents the clinical and microscopic aspects observed in a case of PVL mimicking OLP and discusses the protein expression of CD20 and CD138 for the identification of B cells in the subepithelial inflammatory infiltrate of the lesions. The literature on reported cases of PVL mimicking OLP is also reviewed, in order to outline a clinical and epidemiological profile of these patients, as well as the average time of change from diagnosis to PVL and the average time of malignant transformation.

CASE REPORT

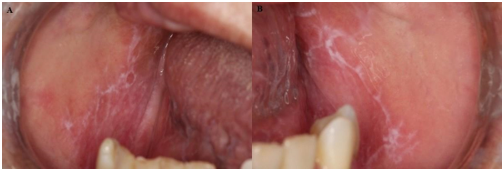

A 66-year-old Latin-American woman presented to the Stomatology Clinic of Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (ICT-UNESP) reporting white patches in her mouth and a burning sensation. During the anamnesis, she denied addictions such as smoking or alcohol consumption. She also reported being hypertensive and the daily use of Losartan® 25 mg orally. On general physical examination, purplish patches were noted in the tibiofemoral joint region. On intraoral physical examination, white striae were bilaterally observed on the buccal mucosa (Figures 1A and B).

Figure 1: Photos of initial clinical manifestations, white striae on the buccal mucosa. A. Right buccal mucosa. B. Left buccal mucosa.

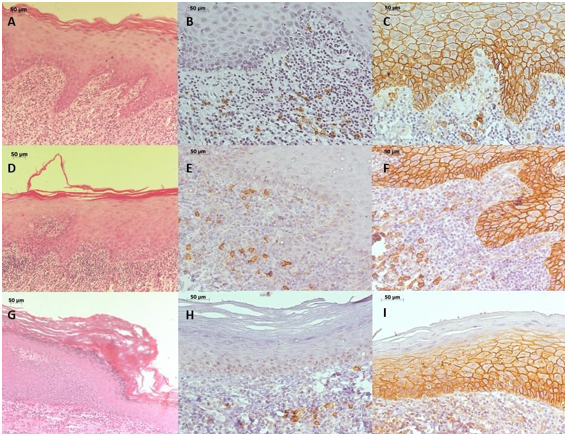

Given the clinical suspicion of OLP and lichenoid reaction (LR), an incisional biopsy was performed on the right buccal mucosa. Microscopic examination revealed a mucosal fragment covered by stratified squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, sawtooth-shaped epithelial ridges, exocytosis towards the lower epithelial portion, and a band of inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate in the lamina propria beneath the epithelium (Figure 2A).

To rule out the clinical hypothesis of LR to Losartan®, the physician was asked to replace the antihypertensive drug, which improved the clinical condition, and the diagnosis of OLP was established. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the patient returned for a follow-up visit three years after the initial diagnosis of OLP. White striae were noticed on the lower lip and tongue edge, multiple white plaques with a leathery surface that had a 5 mm diameter maximum located on the buccal floor, attached gingiva, and alveolar ridge of the mandible on the left and right sides that extended to the buccal mucosa, non-homogeneous and with areas of verrucous appearance (Figures 3A-D).

Figure 3 Photos of clinical manifestations before the second biopsy revealing white striae. A. Lower lip. B. Tongue border. Non-homogeneous and verrucous appearance of white plaque C. Buccal mucosa. D. Lower right alveolar ridge.

Incisional biopsies were performed on the right buccal mucosa and lower anterior gingiva, under the hypothesis of PVL. Microscopically, fragments of the buccal mucosa exhibited ortho-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, with areas of evident granular layer, atrophy, spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis. In the lamina propria, a band of inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate was observed in the subepithelial region (Figure 2. D), and the histopathological diagnosis was compatible with OLP. Examination of the lower anterior attached gingiva showed keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, with an evident granular layer and abrupt change in the keratinization pattern, an area of intense atrophy, rectification of the basal layer and some mitoses not restricted to this layer. The lamina propria showed moderate diffuse chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and the histopathological diagnosis was hyperkeratosis with moderate epithelial dysplasia (Figure 2G). Based on the clinical features of the lesions and the histopathological characteristics, the final diagnosis of PVL was made. The patient is currently under follow-up.

Immunohistochemistry reactions were performed for CD20 and CD138 proteins (Table 1). CD20 and CD138 were diffusely labeled on the inflammatory cells of the connective tissue of all biopsies performed. Epithelial intercellular junctions were positive for CD138 (Figures 2. B, C, E, F, H, and I).

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Pubmed database was used to search for reported cases of PVL with initial presentation as LR or OLP, until April 2023. The MesH terms used for the search were “proliferative verrucous leukoplakia” AND “oral lichen planus” and “proliferative verrucous leukoplakia” AND “lichenoid”. The search yielded 59 and 22 results, respectively. Of these, only case and series reports were studied, resulting in 5 articles. As an inclusion criterion, the articles should be published in English and the patients should have the final diagnosis of PVL but preceded by a diagnosis or clinical appearance of LR or OLP. Of the 5 articles only 3 met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Information collected was: gender, age at initial diagnosis, tobacco and alcohol use, initial diagnosis, the mean time interval from diagnosis of LR/OLP to PVL, a clinical or histopathological final diagnosis of PVL, histological findings, information on verrucous areas or not, whether there was malignant transformation, and how long after the diagnosis of PVL. The epidemiological data of the cases (n=22) is summarized in Table 2. The prevalence was reported in women (n=19), who at the time of diagnosis did not consume tobacco (n=22) or alcohol (n=12), with an initial manifestation of lichenoid areas around 59 years of median age.

Table 2: Data extracted from the cases included in the literature review.

| Lopes et al., 2015 | Garcia-Pola et al., 2016 | McCarthy et al., 2022 | |

| Number of cases | 1 (100%) | 14 (100%) | 7 (100%) |

| Female | 1 (100%) | 11 (78,57%) | 7 (100%) |

| Non/ex-smoker | 1/0 (100/0%) | 11/3 (78,58/21,42%) | 5/2 (71,42/28,57%) |

| Alcohol consumption | 0 (0%) | 3 (21,42%) | NR |

| Average age at initial diagnosis (years) | 64 | 56 | 57 |

| Initial diagnosis | clinical | clinical/histological | clinical/histological |

| PVL diagnosis | clinical/histological | clinical/histological | clinical/histological |

| Mean time interval of diagnosis from OLP/LR to PVL (years) | NR | 4 | 8 |

| Histological findings | mild/moderate epithelial dysplasia | hyperkeratosis and verrucous hyperplasia | verrucous hyperplasia and severe epithelial dysplasia |

| Verrucous areas | 0 | 14 (100%) | 7 (100%) |

| Oral cancer diagnosis - number of cases | 1 (100%) | 4 (28,57%) | 3 (42,85%) |

| Oral cancer diagnosis - how long after PVL diagnosis | 15 months | average of 9 years | average of 11 months |

NR- non reported.

In 21 cases, the initial diagnosis of LR or OLP was confirmed by biopsy, and the average time of diagnosis change from LR or OLP to PVL was 6 years. The diagnosis of PVL was made clinically and histologically and only one case did not have a verrucous aspect. 8 of 22 cases progressed to squamous cell carcinoma, with a median of 3.7 years after the initial diagnosis of PVL (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study reports the case of a patient who initially presented clinical and microscopic characteristics similar to LR and OLP, as she presented white striae on the buccal mucosa and was using antihypertensive medication (21,22). The antihypertensive medication was replaced by the physician and there was no change in her lesions, ruling out the diagnosis of LR (21). After 4 years of follow-up, there was a change in the clinical scenario and the hypothesis of PVL was formulated, since it has an epidemiology similar to that described in OLP (15,16). PVL is characterized by multifocal white plaques, which may or may not have a verrucous surface (8,15). Plus, in the early stages, it may present a striated pattern as in OLP (23).

PVL and OLP also share similar microscopic characteristics, as PVL can present a banded lymphocytic infiltrate, favoring a misdiagnosis of LR or OLP(5,10,11,13,17,19,24-26). What contributed to the differentiation between LR, OLP, and PVL is the presence of epithelial dysplasia and a papillary/verrucous surface that are absent in LR and OLP. However, these findings may not be present in early cases of PVL (14,21,27,28). The incisional biopsies of the buccal mucosa in this case met the microscopic criteria for OLP. However, one of the fragments from the second biopsy revealed the presence of epithelial dysplasia and an abrupt change in the keratinization pattern, favoring the diagnosis of PVL.

Although there are no biomarkers to differentiate between PVL and OLP, some proteins, such as CD20 and CD138, can contribute to the prognosis. CD138 is useful to reveal the cohesion between epithelial cells: the greater the degree of dysplasia, the lower the CD138 staining at epithelial intercellular junctions (24). In this report, there was immunopositivity for CD138 among epithelial cells, as there was moderate dysplasia. Its hypoexpression indicates dysregulation of cell adhesion, increasing the spread of neoplasm cells due to lower adherence and resistance to apoptosis, associated with a worse prognosis (30-32). CD138 expression was also noted in the inflammatory cells present in the lamina propria, revealing the presence of B lymphocytes or plasma cells that are not normally seen in OLP (33), contrasting with the findings of Mahdavi et al. (34), who reported B cells in the inflammatory infiltrate of OLP through protein expression of CD20. In this report, CD20 expression was observed in the subepithelial inflammatory infiltrate. Characterization of the cells present in the inflammatory infiltrate, using CD20 and CD138 antibodies, was not useful to distinguish OLP from PVL, but analysis of CD138 expression is valid for assessing the cohesion between epithelial cells.

The question as to whether OLP turned into PVL or PVL initially presented with characteristics of OLP has been discussed. Lopes et al. (13), reported a case of a woman who presented white striae with atrophic areas in the buccal mucosa bilaterally with the hypothesis of LR excluded after metal restorations were replaced without resolution. Incisional biopsies revealed hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with mild epithelial dysplasia, suggesting the diagnosis of PVL, similar to the present report. However, after 15 months another biopsy revealed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. Our patient has been followed up for 48 months, with no signs of malignant transformation.

In our report, the transition time from OLP to PVL was similar to Garcia-Pola et al.’s (26) findings, since they reported that 4 years was the average time for the development of multifocal, plaque-like verrucous lesions. In some cases, there was also malignant transformation during the follow-up period(11,26,35).

Malignant transformation of OLP is a subject of great discussion and it occurs in 1.4% of cases (9). Thus, the case series described above could be cases of PVL misdiagnosed as OLP, since PVL may initially present as white spots with lichenoid characteristics, which later evolves into the classic clinical features. It should be included in the differential diagnosis of lesions with lichenoid changes, both clinically and microscopically (27,35).

There is no consensus on whether PVL evolves from OLP, whether its initial presentation mimics OLP, or whether the two lesions can occur simultaneously in the same patient. That being said, the last hypothesis is not supported by any reports published in the current English literature. The hypothesis that PVL mimics OLP is the most plausible for this report, since the biopsy performed during the follow-up period showed clinical and microscopic characteristics similar to OLP and the other to PVL.

CONCLUSIONS

Lesions that appear whitish and are consistent with RL or LPO must be investigated and distinguished from LVP. It's crucial to closely monitor patients diagnosed with whitish lesions, as clinical changes may manifest, and consequently, the diagnosis, which is essential in cases of LVP given its unfavorable prognosis and high rates of malignant transformation.

Additionally, we conclude that the reported cases of LVP mimicking OLP were more prevalent among women who were non-smokers and non-alcohol consumers. The onset of lichenoid areas typically occurs around the age of 59, and the diagnosis of LVP is established, on average, six years later. The malignant transformation occurred in 8 out of the 22 reported cases, with an average of 3.7 years following the final diagnosis of LVP.

texto em

texto em

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI