1. Introduction

In October 2022, nearly 156 million Brazilian went twice to the polls to elect candidates for several legislative and executive offices, at state and federal levels nationwide. A runoff race was held for the presidential office and for governors in almost half of Brazilian states, where no candidate had exceeded 50 % of the votes in the first competition.

This presidential race was intensely fierce and very distinct from all the previous elections since redemocratization. Polarization, violence, fake news, conspiracy theories and dissemination of hate speech took an unprecedented proportion among citizens and candidates. Political scientists engaged in a vigorous debate about the strength or weakness of political institutions and their actual capacity to protect Brazilian democracy (Melo, 2023). The military and the judicial branch were at the center of a controversy over the voting system. The president and their supporters publicly advanced their anti-establishment campaign2 (Meléndez, 2022) while the attorney general kept inert. The legislative branch and most political parties remained as if it was not their business. Electoral governance institutions, in their turn, managed to keep the electoral cycle on track, exactly as they have done for decades.

This article shortly describes the last Brazilian general election in its process, its results, and its implications for Brazilian democracy. The next section briefly presents Brazilian electoral institutions: the electoral system and the electoral governance. The article follows describing the main political actors and their strategies during the electoral process. The second to last part summarizes the results of the electoral process in terms of offices and power distribution and in terms of electoral integrity. Finally, the concluding remarks point out some implications of all that process for the future of Brazilian democracy.

2. Electoral institutions in Brazil

Electoral institutions comprise the rules which turn votes into offices (the electoral system institutions) and those rules on electoral management and adjudication (the electoral governance institutions). The institutions from the first group have been recurrently blamed for the broader set of political problems in Brazil. The second ones, however, were widely taken for granted, since redemocratization until very recently, as stable and trustworthy.

Debates on the Brazilian electoral system usually concern its combination with the government system. Being an emblematic case of coalitional presidentialism (Chaisty, Cheeseman et al., 2018), Brazil is, since the regime transition in the early ’80s, at the center of the scholarly controversies on the (in)adequacy of its political institutions. Its electoral system based on open-list proportional representation (olpr) allows for a highly fragmented party system (Nicolau, 2022). Its combination with a presidential system would explain the lack of governability and would be responsible for hampering the Brazilian party system's institutionalization (Mainwaring & Shugart, 1997; Ames & Power, 2007).

Another problem with Brazilian political institutions would be the instability in competition rules. The Brazilian electoral system has been now and then the target of many failed proposals for constitutional reform. Despite keeping the main features of the electoral system, legislators have, since redemocratization, changed several minor rules (such as financial regulation of campaigns, for example) which yet affect electoral competition (Fisch & Mesquita, 2022). Furthermore, the judiciary has given new interpretations of old rules that work in practice as new rules of the game (Marchetti, 2022).

Despite some disagreement in the literature on the functionality of the Brazilian political system (Figueiredo & Limongi, 1999; Ames, 2003; Mauerberg Junior, Pereira et al., 2015; Alves & Paiva, 2017), there was an unambiguous process of bipolarization at the presidential level (Limongi & Cortez, 2010; Melo & Camara, 2012). For many years, the two major political parties mastered the presidential competition with somewhat disparate political agendas (Arretche, Marques et al., 2019). The Workers Party (pt) and the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (psdb) disputed presidential elections from 1994 to 2014. They were surprised in 2018 by the winning of Bolsonaro, a former military backbencher from a then irrelevant political party. The stable electoral system did not avoid the huge change in the Brazilian party system from 2018 on, when the usual right pole (psdb) was replaced by an extreme-right one (the bolsonarism).3

Beyond the electoral system, electoral governance institutions are also crucial for democracy because they rule the electoral process itself. The Brazilian electoral governance body is the tse (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral)4 which is imbued with both management and adjudication functions. That is, at the management level it organizes and conducts the elections; at the adjudication level it judges electoral litigations and resolves disputes concerning the electoral competition. This institutional design is called non-specialized (Mozaffar & Schedler, 2002) and is also at work in Costa Rica, Panama, and Uruguay.

tse has a highly professional and qualified bureaucracy and a higher council composed mainly of judges from other courts, who alternate each up to four years.5 Like most electoral management bodies (embs) in Latin America, tse is independent of the executive branch. On the other hand, it distinguishes itself from several counterparts in Latin America because it does not have any partisan representative in its higher council, being autonomous also from political parties.

As any emb, the Brazilian electoral justice shares with the legislature some electoral regulatory responsibilities by issuing guidelines (called resoluções), which are operational, infra-legal rules needed to organize and conduct the electoral process. Rulemaking is a definitional component of electoral governance (Mozaffar & Schedler, 2002). Still, as the Brazilian emb is a tribunal inserted in the judicial branch structure, these electoral regulations are sometimes seen either as judicial activism or judicialization of politics (Kerche, 2023; Marona, 2023).

3. Political actors and the 2022 electoral process

Analyses of any electoral process should cover the period called the electoral cycle. However, the 2022 electoral race in Brazil indeed started far before that, as several actions were taken toward the electoral competition as early as the Bolsonaro government began in 2019.

Despite not having any position at the electoral management, the executive branch played a decisive role in the 2022 election. Being a candidate for reelection, the president and their supporters acted to spread distrust in the voting system and the judiciary as a whole. Military, who had been granted many civil offices in the government (Couto, 2021; Passos, 2021), repeatedly confronted electoral authorities criticizing their work, demanding superfluous justifications, raising mistaken questions, requesting sudden meetings, and claiming for extra-legal roles in the certification of electoral procedures.

Several political parties and politicians supported a (failed) proposal for constitutional reform to add vote printers to the electronic voting machines, pleading that they were unreliable, and engaged in misinformation campaigns.6 Other political parties and politicians engaged in intense judicial agenda, suing each perpetrator of each electoral malpractice and petitioning the judicial branch for punishment.

The tse gave two kinds of answers to these demands, according to each of its two functions: the management of elections and the adjudication of election conflicts, granting judicial decisions in legal cases between stakeholders. At the adjudication level, answers were slow, with several cases still pending. Because of its nature of a judicial court, tse can only act after the facts for depending on a filed lawsuit.

At the electoral management level, however, the action was assertive and quick. Regarding the reliability of the voting and counting process, tse launched extensive media and internet informative campaigns and created an electoral transparency committee (Comissão de Transparência das Eleições) to which many representatives of social organizations and academies were invited.7 Regarding the recurring complaints from the military, tse issued public documents describing and explaining every procedure and security resources and stressing their own legitimacy and constitutional prerogatives to make electoral management decisions.

The 2022 electoral campaign saw more misinformation than ever before. Government supporters falsely claimed fraud and manipulation by the tse members and had their stories quickly spread through social media and message apps. At the management level, tse fought electoral misinformation through agreements with the press, fact-checking organizations, internet service providers, and political parties (Osorio, Alvim et al., 2022) and through informative campaigns in social media.8 At the adjudication level, tse received and processed countless demands to withdraw content from internet channels.

For many years, Brazilian elections have deployed several electronic technologies at every step of the process: voters are identified through biometrics (fingerprint scan), voting machines collect and record votes electronically, votes are tallied electronically, and all of this without involving internet connection, so the process is not vulnerable to external attacks. These technologies assure the secrecy of the vote and transparency and auditability of everything else. For many years, they have prevented fraud and deserved comprehensive trust from Brazilian society until a few years ago.

The dissemination of distrust in the voting process was part of some political actors’ (the president and his supporters) electoral strategy to grow defiant voters, undermine credibility on tse, and build a kind of alibi in case of electoral defeat. The primary evidence of that is the selectivity of the criticisms: electronic voting records for several other offices (deputies, for example) on the same election day, using the same voting machines, were not put under suspicion.

Political violence also increased, reaching in the electoral periods of 2020 and 2022 its higher levels since it began to be measured (giel, 2022). Beyond attacks against politicians, violence also affected ordinary citizens with or without political alignment. Curses and verbal aggressions overflowed from the candidates’ contest to everyday life, probably related to the «strategic extremism as a campaign to cultivate insurgents during the whole mandate» (kalil, 2022). The press reported 15 murders and 23 attempted homicides related to political competition during the electoral campaign period (Anjos, Paes et al., 2022).

4. The results of 2022: political power and electoral integrity

The political system that emerged from the 2022 general election is deeply distinct from the recent Brazilian political history. Increased polarization in the presidential competition and decreased trust in the electoral management make a disturbing scenario for the future.

The electoral cycle started with party conventions in July and finished with the certification of elected candidates in December. The electoral campaign began after registration of candidacies in August and lasted until election day eve. In order to face campaign spendings, political parties counted on public funds, free broadcasting time on tv networks, and donations from citizens.9

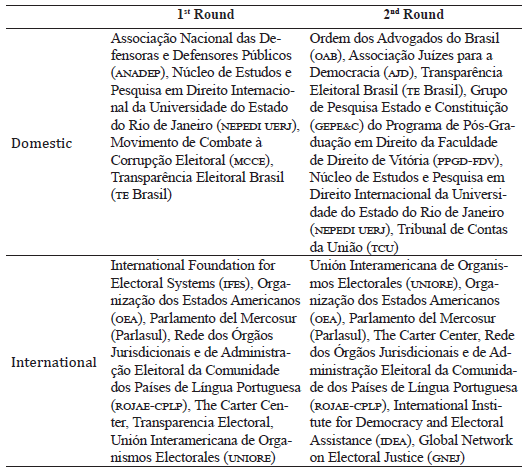

The voting and tallying processes in both rounds were observed by several domestic and international missions listed in table 1.

Table 1 Reports issued by Electoral Observation Missions

Source: tse (https://www.tse.jus.br/eleicoes/eleicoes-2022/ missoes-de-observacao-eleitoral)

The reports from observers coincided in that the election was fairly conducted. However, Brazilian political scientists pointed out several electoral malpractices committed by the government as evidence of unfair competition. For example, during the campaign, President Bolsonaro distributed provisional financial benefits, employed public resources in travels and motorcycle rallies nationwide, and spread fake news and conspiracy theories through the internet. He also handled federal institutions like the highway police and a state public bank to get electoral advantage.

The results of the election were announced a few hours after polling stations were closed, bringing remarkable changes to the Brazilian party system. The main transformations were the brand-new power distribution among political parties, a raised suspicion about electoral governance institutions, and a generalized hatred dividing the society.

The narrow victory of former president Lula over Bolsonaro yielded a hostile environment between supporters of each side. Crowds took to the streets celebrating the election while truck drivers protested against it blocking roads across the country. The president’s party (pl, Partido Liberal) alleged irregularities in the voting machines of specific poll stations where its candidate has lost. Bolsonaro took two days to publicly recognize his defeat and flew to the us before the inauguration to avoid the swearing ceremony.

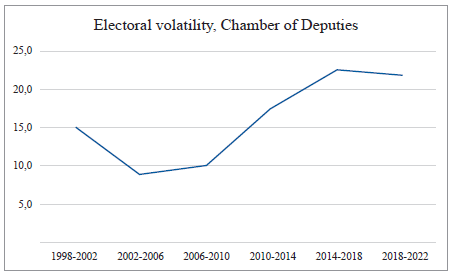

Regarding the legislative election, right-wing parties won a bigger share of the seats. Traditional parties such as psdb shrunk considerably while pl, Bolsonaro’s party, which always had an insignificant caucus, became the biggest one in the Chamber of Deputies. Electoral volatility (Pedersen, 1980) kept high in 202210 after having sharply increased in 2018, as graph 1 shows. Between 2018 and 2022, electoral volatility in Brazil reached the figure of 21.8, smaller than the average found by Mainwaring and Torcal (2005) for the 1978-2002 period.

High electoral volatility is the classic indicator of low institutionalization of party systems (Mainwaring & Scully, 1995; Mainwaring & Torcal 2005). Brazil had a disruptive election in 2018, with a small party (psl) turning into a big one through the coattail effect of its presidential candidate over the legislative candidates. In 2022, the same presidential candidate changed to another party (pl) to which he carried his massive voters also in the legislative competition.

In the past, Brazilian political scientists argued that electoral volatility was not so high (Mainwaring, Power et al., 2018) and that it has declined since the democratic transition, especially when measured at the subnational level (Bohn & Paiva, 2009). Volatility in the young Brazilian democracy would reflect the supply side variation, allowing accountability and vitality to the politics (Peres, 2013). Furthermore, the fluctuation in electoral support did not reach the main political parties (Tarouco, 2010). The 2022 election may have put Brazil back on the list of unstable, inchoate party systems, where a party’s electoral performance in an election is not a good predictor of its performance at the next one.

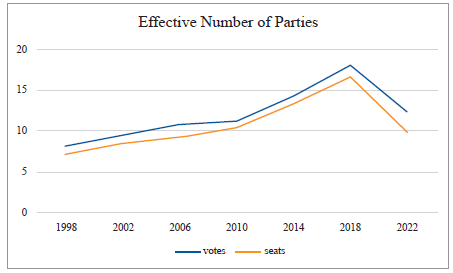

Beyond changing hands, political power also became a little bit less diffuse. Measured in terms of seat’s distribution at the Chamber of Deputies, party fragmentation decreased, in contrast with its former ascendant trajectory, as graph 2 shows.11 Two recent reforms explain such shrinkage as compared with the last general election: parties coalitions became forbidden in proportional representation competitions and parties must reach the threshold of 1.5 % of national votes in order to be entitled to public funds. Despite that, 23 political parties got seats in the chamber of deputies (32 have votes).

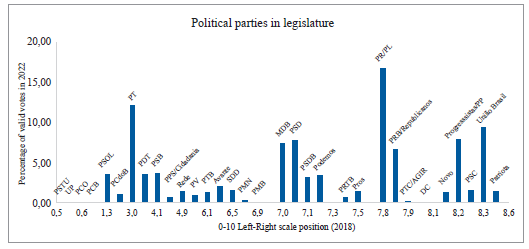

However, the overt polarization of the presidential competition did not echoed in legislative seats. Despite parties spread from left to right,12 the high fragmentation of the system kept their electoral performance low enough to limit polarization at the Chamber of Deputies, as graph 3 shows.

Computed according to Dalton’s (2008) formula, the polarization index of the Brazilian party system that emerged from the 2022 election is as low as 4.2, very close to Switzerland in 2003, 2007, and 2011 and Netherlands in 2010 (Dalton, 2017).13

Women's presence remained very disproportional in the 2022 legislative election, although it has increased from 15 % in 2018 to 18 % in 2022. Brazil has a legal quota of 30 % for women in the lists of candidates. Still, political parties usually bypass it by nominating fake candidates (candidaturas laranja) or refusing party resources or support for the women candidates to be able to do their campaigns.

5. Concluding remarks: Implications

The 2022 election was a challenging test for the young Brazilian democracy. As the populist wave is being pointed as risky in many countries, Brazil has been added to the roll of worrisome cases on backsliding track.

The precedent analysis showed that the Brazilian 2022 election brought along the spread of distrust, violence, high electoral volatility, high party fragmentation, and low presence of women. None of these features allows for a good forecast for democracy.

Sinister prognostics in Brazil are often based on criticisms of its institutions, which would be weak and ineffective. On the other hand, strong institutions would be those with high stability and high enforcement power (Brinks, Levitsky et al., 2020). Moreover, they would make a difference because they affect actors’ expectations about the behavior of others, constraining choices and reducing uncertainty.

Despite the well-known weakness of several Brazilian institutions, the electoral governance one (the tse) fits the stability and enforcement criteria of strong institutions. They have worked for decades assuring electoral rights, fighting and avoiding fraud, and warranting electoral democracy. Public expectations about stability and enforcement of electoral governance institutions used to be high enough to give tse strength to keep the electoral process on track, but not without losses and damages to its public image.

As institutions have not changed since the last election, maybe we should blame the political actors and their strategies for the harm infringed in 2022 on the legitimacy of the Brazilian electoral process. That means that electoral integrity -not to mention the people’s perception of it- does not depend only on the quality of electoral management institutions, as our neo-institutional scholarship would make us expect. Good institutions are not enough for good elections, and institutional reforms are not a panacea.

Malpractices that damage electoral integrity may come from multiple actors outside the electoral institutions (Birch, 2011). In 2022 in Brazil, that was the case. Despite having been fought by the emb, malpractices perpetrated by the government and their supporters downgraded the perception of electoral integrity. Capacity and autonomy of the emb are not enough for election legitimacy.

Preemptively casting doubt on the Brazilian voting system and actively blemishing the perceptions of freedom and fairness of Brazilian elections was a strategy to justify eventual defiance and gather public support for refusing the results. The protests in front of military headquarters demanding intervention and the violence which followed the president’s defeat show how that strategy has indeed been effective in fueling a crowd of antidemocratic citizens.

As this article is being written, the post-election days already saw more than one clue that a coup was being (poorly) prepared. A document was written to step in the emb; the police and military have neglected turmoil and conspiracies against democracy. Besiege, riots, and break into presidential offices, Congress, and Supreme Court buildings at the Three Powers Plaza in Brasília were planned through social media and performed with reluctant reactions from the security forces.

It is symptomatic that the sharp alternation from a right-wing government to a left-wing one and the policy implications expected from that did not deserve the focus of this article. It is hard to predict how this election will change Brazilian democracy from now on.