Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.2 Montevideo dez. 2023 Epub 01-Dez-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2844

Articles

Family conflict and parental engagement: perceptions of teenage children

1 Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brazil, clarissepm@unisinos.br

2 Centro de Estudos da Família e do Indivíduo, Brazil

3 Núcleo de Apoio ao Superendividado do PROCON, Brazil

4 Centro de Estudos da Família e do Indivíduo, Brazil

Family conflicts and low parental involvement can have repercussions on children's development. For this reason, the aim of this study was to investigate teenage members of nuclear and separated families' perceptions of parental involvement and family conflicts, as well as their possible repercussions on internalizing and externalizing symptoms. This is a qualitative study carried out in three public schools, through focus groups and involving nineteen adolescents who also answered a sociodemographic questionnaire and the Youth Self-Report. Descriptive statistical analysis showed that part of the sample had clinical symptoms. The conversations in the focus groups were subjected to content analysis and gave rise to the following categories: family conflicts, parental involvement, internalizing symptoms, and externalizing symptoms. The results made it possible to understand how family interrelationships are perceived by children and impact their way of thinking, feeling, and acting, suggesting the need for spaces to welcome and listen to young people.

Keywords: parent-child relationships; adolescence; family conflict; psychological symptoms.

Os conflitos familiares e o baixo envolvimento parental podem ter repercussões no desenvolvimento dos filhos. Por isso, o objetivo deste estudo foi investigar as percepções de adolescentes, membros de famílias nucleares e separadas sobre o envolvimento parental e os conflitos familiares, assim como suas possíveis repercussões em sintomas internalizantes e externalizantes. Trata-se de uma pesquisa qualitativa realizada em três escolas públicas, através de grupos focais e que envolveu dezenove adolescentes que responderam também um questionário sociodemográfico e o Youth Self-Report. Através de análises estatísticas descritivas verificou-se que parte da amostra apresentou sintomas clínicos. As conversações nos grupos focais foram submetidas à análise de conteúdo e originaram as categorias: conflitos familiares, envolvimento parental, sintomas internalizantes e sintomas externalizantes. Os resultados possibilitaram compreender como as interrelações familiares são percebidas pelos filhos e impactam sua forma de pensar, sentir e agir sugerindo a necessidade de espaços de acolhimento e escuta aos jovens.

Palavras-chave: relações pais e filhos; adolescência; conflito familiar; sintomas psicológicos.

Los conflictos familiares y el escaso involucramiento de los padres pueden tener un impacto en el desarrollo de los niños. El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar las percepciones de los adolescentes, miembros de familias nucleares y separadas, sobre el involucramiento de los padres y los conflictos familiares, así como sus posibles repercusiones en los síntomas internalizantes y externalizantes. Se trata de una investigación cualitativa realizada en tres escuelas públicas a través de grupos focales, que involucró a diecinueve adolescentes, quienes también respondieron un cuestionario sociodemográfico y el Youth Self-Report. Mediante análisis estadístico descriptivo se encontró que una parte de la muestra presentaba síntomas clínicos. Las conversaciones en los grupos focales fueron sometidas a análisis de contenido y originaron las categorías: conflicto familiar, participación de los padres, síntomas internalizantes y síntomas externalizantes. Los resultados permiten comprender cómo las interrelaciones familiares son percibidas por los adolescentes e impactan en su forma de pensar, sentir y actuar, y sugieren la necesidad de espacios de acogida y escucha de los jóvenes.

Palabras clave: relaciones entre padres e hijos; adolescencia; conflicto familiar; síntomas psicológicos.

The eminent increase in emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents and the negative socio-educational impact they cause at this stage of development has aroused concern among health professionals (Borba & Marin, 2017; Mosmann et al., 2017; Zou & Wu, 2020). A worldwide survey carried out more than a decade ago by Patel et al. (2007) concluded that one in five adolescents has some symptomatology characteristic of a psychiatric disorder, and it is estimated that this number is even higher today.

A systematic review of the national scientific literature carried out in 2014 analyzed 27 studies to survey the prevalence of mental disorders in childhood and adolescence and possible associated factors. The study found that the most common disorders in children and adolescents were anxiety, depression, conduct, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and drug abuse. Family configuration and marital conflicts were the main factors associated with symptoms in children and adolescents. Children of divorced parents who witnessed marital fights, for example, could be more at risk of developing psychopathologies (Thiengo et al., 2014).

The model for classifying child and adolescent symptoms suggests dividing them into two groups: internalizing and externalizing. According to the definition proposed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013), internalizing symptoms involve introspective expressions such as anxiety, isolation, sadness, low self-esteem, and depression. Externalizing symptoms are characterized by being more easily observable, expressing themselves through hostility, physical or verbal aggression, and hyperactivity (Achenbach et al., 2014; Lopes et al., 2016).

There is a consensus among researchers in the field that internalizing and externalizing symptoms cause social and developmental damage to adolescents, as they interfere with school performance, friendship, and family relationships (Borba & Marin, 2017; Mosmann et al., 2017; Zou & Wu, 2020). In addition, studies point to the relationship between parental and co-parental problems, marital conflicts, and the triggering of psychopathological symptoms in offspring (Goulart et al., 2016; Mosmann et al., 2017; Mosmann et al., 2018; Rosencrans & McIntyre, 2020). Thus, the interdependence between family subsystems can cause marital conflicts to have a negative impact on children's mental health.

Another variable identified in the literature as relevant to children's mental health is parental involvement. This can occur directly, when there is interaction between parents and children through play and shared free time, or indirectly, through the responsibilities and well-being of the offspring provided by the parents, such as involvement with school, health, and subsistence (Grzybowski & Wagner, 2010). Studies indicate that parental involvement in childhood is associated with better school performance (Ma et al., 2016; Warmuth et al., 2019), and a lower risk of developing depressive symptoms in young adults (Cong et al., 2020).

In addition, parental involvement is a protective factor concerning increased risk behaviors in adolescence, such as engaging in unprotected sexual practices, and drug use, among other behaviors (Savioja et al., 2017). It is also an important factor in the treatment of children and adolescents with different symptoms (Dardas et al., 2018; Iniesta-Sepúlveda et al., 2017; Kreuze et al., 2018).

A study carried out in 2019 explored aspects of the daily lives of three female adolescents about parental separation and the experiences of shared custody concerning parental involvement. The study found that mothers take on the care of their children mainly about school, health, and decision-making, while fathers take on these roles only if mothers cannot be present and mainly concerning financial matters. According to the adolescents, the separation of their parents did not lead to them becoming distant from them, but involvement began to take place based on the roles that each one plays, in other words, based on the gender roles that are traditionally attributed to fathers and mothers (Kostulski et al., 2019).

In Portugal, a survey of thirteen families investigated through focus groups analyzed the perception of parents and children about their conceptions of adolescence, difficulties, challenges, concerns, and strategies for managing difficulties. The participants said that adolescence is a period of experimentation and affirmation and of challenges in the relationship between parents and children, which mainly involve the processes of independence and gender roles - conceptions that girls are fragile and sensitive, but mature, and boys are free to go out with their peers and with fewer demands on their behavior and their first love and sexual experiences. The strategies most often cited by parents and children in the face of dilemmas were promoting autonomy, respecting individuality, discussing limits and rules, parent-child closeness based on trust, dialog, openness and warnings, protection, dedication, attention, and monitoring by parents (Santos, 2013).

In addition to the parental subsystem, specifically the characteristics of the involvement between parents and children, the relational dynamics in the marital subsystem are considered important for understanding what happens to the offspring, since the quality of the marital relationship has an impact on parenting (Costa et al., 2015; Mosmann et al., 2018). Marital conflict is a phenomenon that is often expressed in dyadic love relationships and is related to other factors such as satisfaction, cohesion, intimacy, and marital stability (Costa et al., 2016).

In the face of frequent, intense, and destructively managed conflicts between couples, children tend to be negatively impacted (Mosmann et al., 2017; Mosmann et al., 2018). This impact can be direct if the children become involved in the conflict and are led to position themselves in favor of one parent against the other, or indirect, if the children witness and/or observe the conflicts from a relative distance (Margolin et al., 2001; Minuchin et al., 2009; Rosencrans & McIntyre, 2020; Thiengo et al., 2014). The process by which conflicts in one family subsystem reverberate in other subsystems is called spillover (Erel & Burman, 1995; Hameister et al., 2015).

According to a Brazilian study of 149 couples, children are one of the main reasons for conflict between the couple (Mosmann & Falcke, 2011). For this reason, the authors state that the phenomenon can be bidirectional and interdependent between the marital and parental subsystems. Machado and Mosmann (2020) also point out that adolescents who perceive tension in the family environment tend to have difficulties regulating their emotions, reactive behaviors, lack of impulse control, aggressiveness, and defensive reactions, which contributes to the triggering of externalizing symptoms, especially if parents demand that their children take a stand in the face of conflict.

As explained above, analyzing symptoms in adolescents and the possible triggering factors is a challenge for the research field since the incidence of psychopathologies in this age group is high and involves multiple biological, psychological, contextual/environmental factors, among others (Papália & Feldman, 2013; Thiengo et al., 2014). There is a consensus among studies that the presence of parental involvement and constructive management of family conflicts are considered protective factors as they reduce the risks of developing internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children (Cong et al., 2020; Thiengo et al., 2014; Warmuth et al., 2019). However, most of the studies address the phenomenon from the perspective of parents, other caregivers, and teachers (Cong et al., 2020; Mosmann et al., 2017; Rosencrans & McIntyre, 2020). For this reason, the present study investigated the perception of adolescents, members of nuclear and separated families, about parental involvement and family conflicts, as well as their possible repercussions on internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Participants

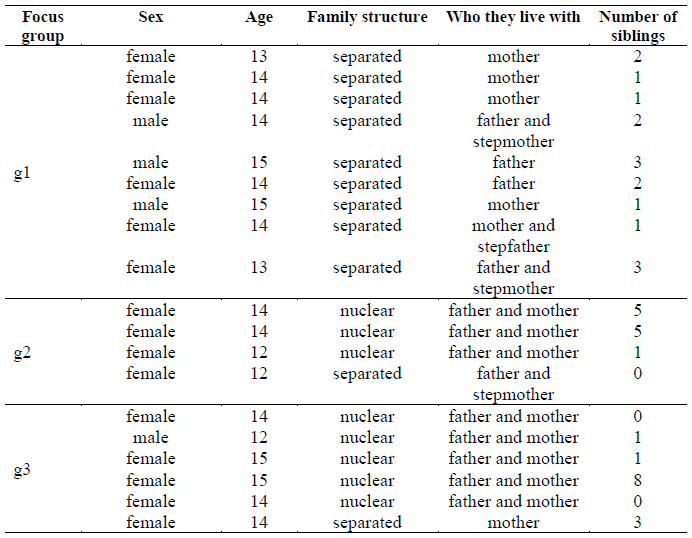

The participants in the study were nineteen adolescents, fifteen girls and four boys, who made up three mixed focus groups - female and male participants from three cities in the inner state of Rio Grande do Sul. All the participants were attending elementary school in public schools, ten were members of first-marriage families, and nine of families with separated parents. Nine adolescents took part in the first group, four in the second, and six in the third. The participants' minimum age was 12 and their maximum age was 15 (M = 13.79; SD = 0.97). Table 1 shows the information described in detail.

The inclusion criteria for taking part in the study were being in the adolescence stage, being the child of parents from first-marriage families, or being separated parents whose parents remained involved in the care and responsibilities related to the adolescent taking part in the study. Participants had to be referred by a school professional, psychologist, teacher, or educator, as they were in care or on a waiting list for psychological care at school or another mental health care center for presenting symptomatic behaviors characterized as internalizing and/or externalizing. Adolescents whose stepfather or stepmother participated in their care as a substitute for the parent who was absent from their parental role, individuals under the age of twelve or over the age of eighteen and without clinical symptoms could not take part in the study, a criterion observed through a referral from the school and verified at the time of the research using specific instruments.

Instruments

A socio-demographic questionnaire, made up of questions about sex, age, schooling, city of residence, number and age of siblings, and family configuration, the latter checking whether co-parenting in separated dyads was actually practiced by the parents.

A focus group, is a technique in which a debate takes place between participants who have something in common. They are generally small and homogeneous and take place in a non-directive environment where topics related to the research objectives are discussed (Minayo et al., 2008). The technique makes it possible to analyze the interactions that take place within the group and the mutual influence between the participants, which spontaneously encourages them to take part in the conversation because they identify with the subject of the debate, allowing individual and collective issues to emerge (Flick, 2009; Minayo et al., 2008). As for conducting the focus group, a main moderator is appointed to introduce, close, and make the transition from one topic to another and encourage participants to express their opinions and an assistant moderator observes and records the main issues, assisting the main moderator (Flick, 2009).

The focus groups in this study were structured as follows: (a) Welcoming: the participants were welcomed by the moderators and research assistants; (b) Opening: the moderators were introduced, the research instrument was filled in, general information was given about the objectives of the meeting, expectations and how it would take place; (c) Warming up: the participants and the research team were introduced; (d) Thematic discussions on five aspects of co-parenting based on provocative theses, i.e. stimuli to start the discussion in the group. The themes and provocative theses are described below.

(1) Joint Coparenting-stimulus: “Maria, a 15-year-old teenager, was invited to go camping with her friends at the weekend, but in order to go, she needed to talk to her parents. Thinking about this situation, what would it be like in your family?”.

(2) Paternal Coparenting Practice-encouragement: “In Vinícius' family, his father is responsible for taking him to school, and taking part in parents' meetings, but prefers not to get involved in important demands or decisions. These are the duties of Vinícius' father, how does this happen in your family?”.

(3) Maternal Coparenting-encouragement: “Vinicius' mother is responsible for making decisions about household chores, authorizing Vinicius to go out, and monitoring/enforcing his grades at school. These are Vinicius' mother's duties, how does this happen in your family?”.

(4) Adolescents' Perceptions of Their Involvement in Coparental Conflict-stimulus: “Pedro, a 14-year-old adolescent, has been invited to spend vacations at his paternal grandparents' house. His mother, however, doesn't agree to the trip and the parents end up arguing. In situations like this, Pedro is confused about who to support. How does this work in your family?”.

(5) Adolescents' Feelings as a Result of Involvement in Coparental Conflict-stimulus: “In all the stories we tell, the characters have some kind of feeling about what happens to them and their parents. How do you feel in these situations?”.

The Youth Self-Report, YSR, was developed by Achenbach et al. (2001) and validated for use in Brazil by Bordin et al. (2013). It is a self-assessment inventory for young people aged between 11 and 18 consisting of 112 items with a response scale ranging from 0 (Not True) to 2 (Very True), and eight dimensions of behavioral problems. In this study, the classification of problems was made considering two main categories: internalizing problems, which include the dimensions of Anxiety/Depression (for example: “I am fearful or anxious”), Withdrawal (for example: “I cry a lot”), and Somatic Complaints (for example: “I have physical symptoms with no biological cause”), and externalizing problems, made up of the dimensions of Social problems (e.g.: “I prefer to be alone than in the company of others”), Delinquent behavior (e.g.: “I steal things at home”), and Aggressive behavior (e.g.: “I get into a lot of fights”). The thinking problems and attention problems scales were not considered for this study (Achenbach, 2001).

Data collection

The first contact for the focus groups was made in schools in three cities in inner-state Rio Grande do Sul. The schools that agreed to take part in the study were selected on the basis of demand, i.e. whether they had students who met the criteria to take part in the study. After the first meeting, a visit was made to the site to present the research materials, namely the research instrument, the Free and Informed Consent Term (FICT) which should be taken by the adolescents for their parents to read and sign if they agreed to their child's participation in the research, and the Term of Assent (TA) for the adolescents themselves to read and sign, informing them that they agreed to take part.

About a week after the visit, the school was contacted again to check that the forms had been returned (FICT and TA) and to schedule the focus groups, which would take place during class time in the space provided by the educational institution. On the day and time scheduled at each school, four members of the research group were present, two moderators and two research assistants, roles that remained the same throughout the three groups. The participants were welcomed by the team, and given a badge to facilitate personal treatment and a clipboard with the survey instrument to be filled in. Once they had filled it in, and with the adolescents positioned in a semicircle with the moderators at the front, a tape recorder in the center of the semicircle, and a camera behind the moderators, the conversations began, according to the structure described in the focus group description. Each meeting lasted approximately 1 hour and 30 minutes, taking into account the completion of the instrument and the discussion.

Data analysis

Initially, descriptive analyses were carried out to obtain a descriptive profile of the participants, calculating means and standard deviations. Descriptive analyses were also used to assess the adolescents' symptoms. The conversations in the focus groups were transcribed in full and subjected to the content analysis procedure by the same members of the research team. The content analysis process involved the stages proposed by Bauer (2008), which are: a) Reading the transcribed material in order to achieve familiarity and satisfactory appropriation of the text; b) Identifying units of meaning capable of forming recognizable patterns; c) Organizing the units of meaning by grouping them into categories; d) Selecting the content manifested within each category that could be representative for discussion.

Ethical issues

The study complied with the guidelines and regulatory standards for research involving human beings, in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos, opinion no. 3.452.422, CAAE no. 88282318.3.0000.5344. The FICT and the TA, read and signed by the parents and the teenagers themselves respectively, informed about the audio and video recording of the focus group and the preservation of the participants' identities. The risks arising from the research, although minimal, involved possible emotional commotion when talking and recalling difficult situations experienced in the family. In these cases, a referral would be made for psychological care at the school clinic of the institution responsible for the research.

Results and Discussion

The descriptive analysis for assessing symptomatology in adolescents used the classification in the Achenbach et al. manual (2014). According to the criteria, a percentage above 90 indicates a clinical profile, a percentage between 84 and 90 indicates a borderline profile and a percentage below 84 indicates a normal profile. For internalizing symptoms, fourteen adolescents scored normal, four scored borderline and one scored clinical. For externalizing symptoms, seventeen adolescents scored normal and two scored borderline. This result is noteworthy because the school only considered students waiting on a waiting list or undergoing psychological counseling. Therefore, this data raises questions about the assessment made by the educational institution that justifies referring a particular student for psychotherapy or psycho-pedagogical follow-up, even if this referral is a way of preventing the worsening of a particular behavior identified by a teacher. One hypothesis that can be raised is that teachers don't have the time to monitor adolescents more closely due to the overload of work in the classroom, leading to referrals to manage issues that are typical of the teenage phase, such as low tolerance for frustration, shame, aggression, among other behaviors.

The content analysis of the conversations between the adolescents in the focus groups formed four categories and built a posteriori. The first refers to the adolescents' perception of conflicts between their parents. It is called family conflict and is divided into the subcategories interparental conflict and marital conflict. The reports on whether or not parents participate in caregiving activities, and the division of tasks and responsibilities form the category favorable and unfavorable aspects of parental involvement. The third category, called internalizing symptoms, presents reports on physical symptoms, such as headaches and body aches, and psychological symptoms, such as fear, sadness, and anxiety. Finally, the fourth category refers to the behavioral problems that characterize externalizing symptoms.

Family conflict

The adolescents' perception of conflicts between their parents was very evident in the focus group discussions and characterized two different types of conflicts: those over interparental issues, i.e. conflicts related to the payment of alimony and the parents' management of the adolescent themselves, and those involving marital issues. In the first subcategory, about interparental conflicts, the participants revealed that “I usually watch and ignore their arguments. I think 'I'm not going to get involved', I'm going to stay quiet in my own place because if I don't it's all on me” (Carla); “But I don't remember doing anything wrong or ‘oh, they're fighting about me’” (Olívia).

Most of the time, they (father and mother) go to their room, then they stay there and start talking louder. Then I realize they're fighting. (...) I think the ideal thing would be for them to call me. Because since they're talking about me, I'd like to know too. Especially because whatever they decide will affect me (Quiara).

In addition, participant Inês explains how conflicts between separated parents occur and how she is involved by the caregivers in the situation:

Oh, because, like, it's not that my parents argue all the time, but now things are calmer, until the beginning of the year they were snapping at each other over the phone. Because my mother always says ‘Oh like, if your father steps in front of my gate I'm going to smash his face in’ (laughs). My father kept saying to my mother, “Like, when are you going to pay your alimony?”. Then sometimes she gets angry with him and says she'll pay it when she feels like it, but then he gets angry and then he comes to me and says ‘You have to tell your mother that she has to pay the alimony’. Then I get overwhelmed about it and most of the time I end up, like, getting angry with him, and then he swears at me, my opinion doesn't count (Inês).

The literature shows that children and adolescents subjected to contexts of high tension as a result of family conflicts are more likely to trigger externalizing symptoms, among other problems, such as low school performance, problems with social skills and interpersonal relationships (Goulart et al., 2016; Thiengo et al., 2014). What was reported by the participants Carla, Olívia and Quiara also demonstrates how the spillover effect occurs in which persistent disagreements and difficulties between the parental dyad spill over into other domains - subsystems - of family life, directly or indirectly impacting the offspring (Goulart et al., 2016).

As for the second subcategory, which addresses marital conflicts, the participants Paula and Quiara said: “Because one day or another they will stop fighting. My father once fought with my mother, you know? Really fighting, leaving the house, because he came home late” (Paula).

I've always been much more afraid of him (father) than my mother, so I hardly ever get involved in their arguments, because I know I'll end up being grounded if I give my opinion. They'll end up fighting, so I always keep it to myself (Quiara).

The reports corroborate relatively consolidated evidence in the scientific literature that interparental and marital conflicts can extrapolate to other subsystems, such as parenting, negatively interfering in the parent-child relationship and mainly impacting the offspring (Costa et al., 2015; Mosmann & Falcke, 2011; Mosmann et al., 2018). The negative impact on parenting can occur through the tightening of rules, excessive supervision and control, harsh punishments (Goulart et al., 2016), and/or the distancing of the adolescent from one or both parents. In the latter case, triangulation can also occur (Margolin et al., 2001; Mosmann et al., 2018), a phenomenon in which a child is induced by the parents to establish an alliance with one parent against the other, leading to a so-called coalition that causes significantly deleterious effects on the offspring (Minuchin et al., 2009).

Favorable and unfavorable aspects of parental involvement

Concerning the favorable and unfavorable characteristics of parental involvement, the adolescents' perceptions show interactions between parents and children that are sometimes positive and sometimes negative. Participants Inês, Rita, and Quiara reported: “My father doesn't take me to school, I walk and he doesn't come to meetings either” (Inês).

My father has always been very absent, you know, so I think it's good. I think my father is making a lot of effort, but my mother is fine, you know? Because she's not making much of an effort, I hardly see her, she doesn't talk to me much (Rita).

And my father doesn't really raise his voice to my mother, he's never raised a hand, he's never wanted to hit her, he's never shouted at her like that. As for me, yes, he's raised his hand, he's shouted, he's more aggressive towards me (Quiara).

In addition, the participants revealed characteristics of the interaction with their parents that indicate low parental involvement, an aspect that is evident when parents are permissive and/or negligent in caring for their children. Participant Eliana revealed that she missed her parents' emotional support:

Emotionally, it's always been me. I have to cope with everything on my own. There was a time when my mother helped me get help from a psychologist because she saw that the situation was getting more difficult, but, like, she herself didn't (seek help from a psychologist). She doesn't even have time, because she works and then she provides for the house, so she doesn't have time to take care of our emotional life or hers, you know (Eliana).

In a similar direction, participant Beatriz said: “So, I end up doing almost everything, I take my sister, I come to school on my own and so on” (Beatriz).

The conversations that formed this category confirm the scientific evidence that weaknesses in parental involvement can contribute to triggering symptoms in children (Dardas et al., 2018; Iniesta-Sepúlveda et al., 2017; Kostulski et al., 2019; Kreuze et al., 2018; Savioja et al., 2017). Adolescence is undoubtedly a challenging phase for parents who need to relax certain rules so that adolescents develop autonomy to make decisions, acquire relative independence, and take on more responsibility (Papália & Feldman, 2013). At this stage, children also need close monitoring from their parents, who will provide support in times of crisis and, above all, a safe reference with whom they can "clash" in order to strengthen the process of individualization.

Therefore, the results indicate that adolescents perceive and name the absences and failures in paternal and maternal parental involvement and, consequently, have developed dysfunctional strategies to deal with their problems, such as resignation, self-sufficiency, and isolation. In addition, the perception of a family environment affected by conflicts, whether marital and/or co-parental and by low parental involvement can have repercussions in terms of feelings of guilt and sadness in some adolescents and aggressive behavior in others.

Internalizing symptoms

In the focus groups with the adolescents, reports emerged that characterized physical symptoms and symptoms called internalizing (Achenbach et al., 2001; Achenbach et al., 2014), that is, psychological symptoms such as anxiety, sadness, depression, and psychological states such as low self-esteem and isolation, as also described in the APA (2013). Adolescents report, for example, that:

It's very difficult (referring to talking to parents at the same time), because I'm afraid of my mother's response, I feel trapped. I used to think: 'I wonder what they're talking about? I'm also afraid of my father, because he's already very aggressive (Olívia).

In addition to Olivia, another participant describes fear and guilt as feelings arising from certain interactions with parents:

There's also a knot here, like a feeling of guilt. Feeling guilty because they're fighting over us. (...) I was afraid it was something I'd done wrong, but I couldn't think of anything I'd done wrong (Quiara).

In addition, one teenager reported how she felt when she was prevented from taking part in a debate between her parents, despite her attempts to put forward her ideas. Rita says the following:

I got scared, and angry (when her parents fought). I didn't like it at all, because they didn't even let me speak, they just left me there listening to what they were saying, but I couldn't say anything. Every time I tried to speak, they interrupted me and wouldn't let me speak, saying that it was their business, and that children shouldn't interfere (Rita).

Participant Paula also reports that she “felt physical pain” when she witnessed her parents fighting, especially if she suspected it was because of her. Similarly, Quiara said she felt headaches after arguing with her parents:

Yeah, then I went for a walk because it helped a lot, you know, I already had a headache and I couldn't listen anymore. I was already tired. Then I went for a walk, so I went to my friend's house and got it off my chest (Quiara).

Olivia's and Quiara's accounts of the fear and guilt associated with them committing some inappropriate behavior, Rita's accounts of fear, anger, and frustration, and Paula's and Quiara's accounts of physical symptoms, show how much their children are impacted by what they observe in the family relationship dynamic. In some cases, it involves the adolescents' concern that they are responsible for what happens in their parents' relationship, and in others, the attempt to help the adults resolve problems and conflicts. These findings corroborate the literature on the reverberations that dysfunctional family dynamics have on children (Costa et al., 2015; Mosmann et al., 2017; Mosmann et al., 2018; Rosencrans & McIntyre, 2020; Thiengo et al., 2014), clarifying the nature of the phenomenon and how it occurs in family interrelationships.

In addition to not preserving their children from conflict situations, the reports may show that parents are unaware of what happens to their offspring in these circumstances. In cases where there is a fixed conflictual interaction pattern between parents, adolescents may isolate themselves even more and move away from the family context in order to preserve their own identity. This can be a risk factor for drug use, involvement in problematic interpersonal relationships in adulthood, and unruly behavior that can be mistaken for typical adolescent behavior, diverting attention from the source of the problems.

Externalizing symptoms

During the discussions that took place in the focus groups, a number of stories show descriptions that characterize externalizing symptoms, which are more easily observed as they are expressed through hostility, physical or verbal aggression, and hyperactivity (Achenbach et al., 2014). Olivia's narrative elucidates the externalizing symptomatology:

Mom, I had a fight with someone at school, I'm angry, and one day I'm going to hit them and that's it. So I used to go to the health center on Thursdays, I think I went once, not just three times, to talk to the psychologist and I went twice to the guardianship council to talk to the psychologist there too, to find out why I had a lot of problems at school. I still have problems today, but I don't have the same problems as before when I used to fight a lot. And my parents already thought that I was very angry, these kind of things (Olívia).

Furthermore, in Paula's story, the fighting behavior seems to be a strategy to get her parents to listen to her or even a learned way of dealing with situations. The participant reveals:

I really agree with this, that they should have more trust in us and not buy into the chatter of anyone passing by on the street. Like, coming home and saying, 'oh, so-and-so said that about you, is it true?' Then, I don't know why, I start arguing with my mother. Then they don't even ask, they start fighting too (Paula).

Finally, when her parents prevent her from doing something, like seeing her boyfriend, Olivia does what she calls a "whine":

I think you can achieve anything with drama, right? And so I whined to my mother to let me go and then she saw that I really wanted to go, it had been a long time since we'd been dating and stuff. So I grumbled and huffed at her, but I tried to swallow the air, to keep quiet, you know? To prevent me from saying anything, because otherwise I'd end up arguing with my mother (Olívia).

When she realized that her parents hadn't reached a consensus on a decision about her, Olivia also added: "Then, I usually end up fighting when the situation ends up being that one parent says yes and the other doesn't. In the end, I don't go".

Externalizing symptoms tend to attract more attention from parents and school since they interfere with interpersonal relationships as well as have a negative impact on the individual themselves (Lopes et al., 2016), according to Olivia's description of problems at school, referrals for psychological care and her parents' perception that she was "rebellious". In addition, the report shows how challenging it is to differentiate behaviors characteristic of adolescence from those that are a reflection of a dysfunctional family context (Dardas et al., 2018; Iniesta-Sepúlveda et al., 2017; Kreuze et al., 2018). In the latter case, adolescents can learn destructive ways of solving problems and regulating emotions in situations of conflict, tension, and stress (Machado & Mosmann, 2020), issues that are added to the transitions that occur during adolescence (Thiengo et al., 2014).

Final considerations

The aim of this study was to investigate the perception of adolescents, members of nuclear and separated families, about parental involvement and family conflicts, as well as their possible repercussions on internalizing and externalizing symptoms. With regard to symptoms, the results suggest that focus groups are an effective method of collecting data even if the participants are heterogeneous groups, in this case, adolescents with and without clinical symptoms. It should also be noted that the participants who were most involved in the discussions were those who scored externalizing and internalizing symptoms, which indicates a tendency in these participants to express how they feel.

Although the existence of symptoms and participation in debates may be due to other aspects, the results make it possible to reflect on the family dynamics of these young people who are more "used" to dealing with conflict situations in the family environment and low parental involvement. From this perspective, it may be the case that the symptom-free adolescents remained in the groups as observers, since the "provocative theses" and the conversation did not prompt the need to present their points of view and experiences.

In addition, it was possible to observe that many teenagers, feeling represented by the experience/speech of the other group member, only made affirmative gestures with their heads or laughed when they identified the similarities in the experience reported by the other group member. Therefore, the fact that the focus groups were conducted by two moderators was essential to ensure that one was attentive to the debate and the other to the non-verbal communication that was taking place in parallel. This reflection can also be extended to the lack of verbal participation by the boys, a result that caught the attention of the study's authors. On the other hand, this aspect may indicate that male adolescents find it more difficult to express ideas and feelings, specifically those related to family dynamics, when compared to girls. This result may point to issues related to traditional gender roles, a reflection of family, social and cultural functioning, and structures in which boys are still encouraged to be strong, courageous, and powerful and discouraged from being sensitive to relationships and expressing feelings such as empathy, unlike girls.

Finally, this study has shown how family relationships are perceived by adolescent children and, above all, how they impact their way of thinking, feeling, and acting. This result suggests that individual and/or collective listening and welcoming spaces are opportune resources for identifying symptoms and making the necessary referrals. Misconceptions that adolescents tend to express themselves less may indicate management problems for parents, teachers, and professionals and therefore need to be overcome.

Furthermore, as this was an exploratory study with very heterogeneous groups, i.e. adolescents from nuclear and separated families, with and without clinical symptoms, male and female, the debates may have reduced the possibility of communications and expressions that were richer in detail and other content. Another possibility is that some teenagers adopt a characteristic posture of social desirability, obstructing more sincere communications and expressions that are representative of what happens in the family context due to the fact that they are in a research/evaluation space and are afraid of being labeled and judged.

It is also essential that other studies investigate the teenage population more specifically, since scientific studies with individuals at this stage of the vital/developmental cycle are scarce, especially in Brazil. Further research, with clinical and non-clinical samples of adolescents, could help to build up a robust body of scientific evidence from the Brazilian context and provide indications for better management with adolescents and their parents and with educational institutions, whether from a perspective of prevention, health prmotion and/or intervention.

REFERENCES

Achenbach, T. M. (2001). Manual for ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families. [ Links ]

Achenbach, T. M., Dumenci, L., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Ratings of relations between DSM-IV diagnostic categories and items of the CBCL/6-18, TRF, and YSR. University of Vermont. [ Links ]

Achenbach, T. M., Rescorla, L. A., Dias, P., Ramalho, V., Lima, V. S., Machado, B. C., & Gonçalves, M. (2014). Manual do sistema de avaliação empiricamente validado (ASEBA) para o período pré-escolar e escolar: um sistema integrado de avaliação com múltiplos informadores. Psiquilíbrios. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association. [ Links ]

Bauer, M. W. (2008). Análise de conteúdo clássica: Uma revisão. Em M. W. Bauer, & G. Gaskell, Pesquisa qualitativa com texto, imagem e som: Um manual prático (P. A. Guareschi, trad., 7ª ed., pp. 189-217). Vozes. [ Links ]

Borba, B. M. R., & Marin, A. H. (2017). Contribuição dos indicadores de problemas emocionais e de comportamento para o rendimento escolar. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 26(2), 283-294. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v26n2.59813 [ Links ]

Bordin, I. A., Rocha, M. M., Paula, C. S., Teixeira, M. C. T. V, Achenbach, T. M., Rescorla, L. A., & Silvares, E. F. M. (2013). Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher’s Report Form (TRF): An overview of the development of the original and Brazilian versions. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 29(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2013000500004 [ Links ]

Cong, X., Hosler, A. S., Tracy, M., & Appleton, A. A. (2020). The relationship between parental involvement in childhood and depression in early adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 173-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.108 [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., Cenci, C. B., & Mosmann, C. P. (2016). Conflitos conjugais e estratégias de resolução: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Temas em Psicologia, 24(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.1-22 [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., Falcke, D., & Mosmann, C. P. (2015). Marital conflicts in long-term marriages: Motives and feelings. Psicologia em Estudo, 20(3), 411-423. https://doi.org/10.4025/psicolestud.v20i3.27817 [ Links ]

Dardas, L. A., van de Water, B., & Simmons, L. A. (2018). Parental involvement in adolescent depression interventions: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. International journal of mental health nursing, 27(2), 555-570. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12429 [ Links ]

Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108-132. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108 [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009). Introdução à pesquisa qualitativa (3ª ed.). Artmed. [ Links ]

Goulart, V. R., Wagner, A., Barbosa, P. V., & Mosmann, C. P. (2016). Repercussões do conflito conjugal para o ajustamento de crianças e adolescentes: Um estudo teórico. Interação em Psicologia, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.5380/psi.v19i1.35713 [ Links ]

Grzybowski, L. S., & Wagner, A. (2010). Casa do pai, casa da mãe: A coparentalidade após o divórcio. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26(1), 77-87. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722010000100010 [ Links ]

Hameister, B. D. R., Barbosa, P. V., & Wagner, A. (2015). Conjugalidade e parentalidade: Uma revisão sistemática do efeito spillover. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 67(2), 140-155. [ Links ]

Iniesta-Sepúlveda, M., Rosa-Alcázar, A. I., Sánchez-Meca, J., Parada-Navas, J. L., & Rosa-Alcázar, Á. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral high parental involvement treatments for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 49, 53-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.03.010 [ Links ]

Kostulski, C. A., Arpini, D. M., & Goetz, E. R. (2019). Novas experiências no exercício da parentalidade: O relato de filhas adolescentes em vivência de guarda compartilhada. Contextos Clínicos, 12(3), 949-975. https://doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2019.123.12 [ Links ]

Kreuze, L. J., Pijnenborg, G. H. M., de Jonge, Y. B., & Nauta, M. H. (2018). Cognitive-behavior therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of secondary outcomes. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 60, 43-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.10.005 [ Links ]

Lopes, C. S., Abreu, G. D. A., Santos, D. F. D., Menezes, P. R., Carvalho, K. M. B. D., Cunha, C. D. F., & Szklo, M. (2016). ERICA: Prevalência de transtornos mentais comuns em adolescentes brasileiros. Revista de Saúde Pública, 50, 14s. https://doi.org/10.1590/S01518-8787.2016050006690 [ Links ]

Ma, X., Shen, J., Krenn, H. Y., Hu, S., & Yuan, J. (2016). A meta-analysis of the relationship between learning outcomes and parental involvement during early childhood education and early elementary education. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 771-801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9351-1 [ Links ]

Machado, M. R., & Mosmann, C. P. (2020). Coparental conflict and triangulation, emotion regulation, and externalizing problems in adolescents: Direct and indirect relationships. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 30. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4327e3004 [ Links ]

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3 [ Links ]

Minayo, M. C. S., Souza, E. R., Constantino, P., & Santos, N. C. (2008). Métodos, técnicas e relações em triangulação. Em M. C. S. Minayo, S. G. Assis, & E. R. Souza (Orgs.), Avaliação por triangulação de métodos: abordagem de programas sociais (pp. 71-103). Fiocruz. [ Links ]

Minuchin, S., Nichols, M. P., & Lee, W. Y. (2009). Famílias e casais: Do sintoma ao sistema. Artmed. [ Links ]

Mosmann, C. P., Costa, C. B., Einsfeld, P., Silva, A. G. M., & Koch, C. (2017). Conjugalidade, parentalidade e coparentalidade: Associações com sintomas externalizantes e internalizantes em crianças e adolescentes. Estudos de Psicologia, 34(4), 487-498. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752017000400005 [ Links ]

Mosmann, C. P., Costa, C. B., Silva, A. G. M., & Luz, S. K. (2018). Children with clinical psychological symptoms: The discriminant role of conjugality, coparenting and parenting. Temas em Psicologia, 26(1), 429-442. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.1-17Pt [ Links ]

Mosmann, C., & Falcke, D. (2011). Conflitos conjugais: Motivos e frequência. Revista da SPAGESP, 12(2), 5-16. [ Links ]

Papália, D. E., & Feldman, R. D. (2013). Desenvolvimento Humano (12ª ed.). Artmed. [ Links ]

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & Mcgorry, P. (2007). Series Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369, 1302-1313. [ Links ]

Rosencrans, M., & McIntyre, L. L. (2020). Coparenting and child outcomes in families of children previously identified with developmental delay. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 125(2), 109-124. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-125.2.109 [ Links ]

Santos, S. R. R. (2013). A adolescência e a relação entre pais e filhos no século XXI: Um estudo qualitativo de visões sobre visões (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Portucalense. [ Links ]

Savioja, H., Helminen, M., Fröjd, S., Marttunen, M., & Kaltiala-Heino, R. (2017) Parental involvement, depression, and sexual experiences across adolescence: A cross-sectional survey among adolescents of different ages. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 5(1), 258-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2017.1322908 [ Links ]

Thiengo, D. L., Cavalcante, M. T., & Lovisi, G. M. (2014). Prevalência de transtornos mentais entre crianças e adolescentes e fatores associados: Uma revisão sistemática. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 63(4), 360-372. https://doi.org/10.1590/0047-2085000000046 [ Links ]

Warmuth, K. A., Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2019). Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 301-311 https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000599 [ Links ]

Zou, S., & Wu, X. (2020). Coparenting conflict behavior, parent-adolescent attachment, and social competence with peers: An investigation of developmental differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(1), 267-282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01131-x [ Links ]

Funding: Research funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), call no. 12/2017.

How to cite: Mosmann, C. P., Costa, C. B., Schaefer, J. R., & Peloso, F. C. (2023). Family conflict and parental engagement: perceptions of teenage children. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-2844. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2844

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. C. P. M. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; C. B. C. in a, b, c, d, e; J. R. S. in a, b, c, d; F. C. P. in a, b, c, d.

Received: January 31, 2022; Accepted: October 10, 2023

texto em

texto em