Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.1 Montevideo 2023 Epub 01-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2841

Original Articles

Multilevel schools in an indigenous context: strengths, limitations and challenges from the perspective of teachers in La Araucanía

1 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile, karias@uct.cl

2 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

3 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

4 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

The article presents the main strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, from the voices of teachers in La Araucanía, Chile. The methodology is qualitative and involved six semi-structured interviews with teachers. The technique for analyzing the information is content analysis in conjunction with grounded theory. The results reveal the persistence of prejudices towards indigenous families, the teachers’ lack of knowledge about local ways of knowing and the lack of competencies to develop education in an intercultural perspective. We conclude that there is a need for engagement and dialogue between the school, family and community, which would enable a revitalization of the socio-cultural identity in the teaching and learning processes.

Keywords: indigenous culture; school education; teaching and learning; indigenous and tribal people; intercultural education

El artículo expone las principales fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena, desde las voces de los profesores en La Araucanía (Chile). La metodología es cualitativa, se aplicaron seis entrevistas semiestructuradas a profesores; la técnica de análisis de la información es el análisis de contenido en complementariedad con la teoría fundamentada. Los resultados revelan la persistencia de prejuicios hacia la familia indígena, el desconocimiento de los profesores sobre los saberes locales y la carencia de competencias para desarrollar una educación en perspectiva intercultural. Se concluye la necesidad de vinculación y diálogo entre escuela-familia-comunidad, lo que permita la revitalización de la identidad sociocultural en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: cultura indígena; educación escolar; enseñanza y aprendizaje; pueblos indígenas y tribales; educación intercultural.

O artigo expõe as principais fortalezas, limitações e desafios da escola multinível em um contexto indígena, a partir das vozes de professores em La Araucanía, Chile. A metodologia é qualitativa, foram aplicadas seis entrevistas semiestruturadas, a técnica de análise da informação é a análise de conteúdo em complementaridade com a teoria fundamentada. Os resultados revelam a persistência de preconceitos em relação à família indígena, o desconhecimento dos professores sobre os saberes locais e a carência de competências para desenvolver uma educação com perspectiva intercultural. Concluímos sobre a necessidade de articulação e diálogo entre escola-família-comunidade, que permita a revitalização da identidade sociocultural nos processos de ensino e aprendizagem.

Palavras-chave: cultura indígena; educação escolar; ensino e aprendizagem; povos indígenas e tribais; educação intercultural.

The school is conceived of as an institution recognized by the State for the transmission of Chile’s socio-cultural heritage to new generations, from the logic of the dominant society (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022). In indigenous educational contexts, the school should respond to and address the social, cultural and linguistic diversity of the students present in the teaching and learning processes. This would result in a school education with social, cultural, linguistic and territorial relevance, contributing to the cultural and psychosocial development of ethnic groups in their formal schooling process (Sabzalian, 2019).

In an indigenous context, the school is characterized as multilevel, which means that a single elementary school teacher teaches all students from first through sixth grade in a single classroom (Arias-Ortega, 2020). Historically, this type of school was installed in indigenous territory, mainly to push forward the evangelization process of indigenous children and, in the case of La Araucanía, of Mapuche children and youth. However, over the years, multilevel schools became deep-rooted in colonized indigenous territory and today are characterized by an inadequate structure that fails to offer a teaching and learning process that ensures the schooling and educational success of indigenous children (Matengu et al., 2019). Likewise, these schools historically have low scores in standardized tests on a national level (Arias-Ortega & Quintriqueo, 2021). Furthermore, these schools are notable as being home to rural and indigenous populations with territorial contexts that include the highest rates of social vulnerability in the country.

The purpose of the article is to provide an account of the strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, as told by teachers in La Araucanía, Chile.

The school in an indigenous context: a global and local perspective

A global and local look at countries such as Canada, New Zealand, Mexico, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile reveals similar experiences in schools in indigenous contexts: 1) the existence of assimilationist educational policies, used to educate indigenous people in keeping with the logic of the dominant society. Historically, indigenous children in school education have been humiliated and forced to endure psychological violence, punishment, and sexual and physical abuse, promoting “cultural genocide” (Commission de Vérité et Réconciliation du Canada, 2015; Dillon et al., 2022); 2) the teaching of educational content that minimizes and erases their own history, transmitting educational content that prevents indigenous students from identifying with the history of their people (Harcourt, 2020; Manning & Harrison, 2018); 3) strained educational relationships between teachers and indigenous students, as a consequence of the lack of knowledge of local and cultural history and the principles behind indigenous education. This limits their learning and in turn generates monocultural disciplinary knowledge and increases prejudice by assuming that indigenous people are cognitively lacking (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022; EagleWoman, 2022); 4) pedagogical practices are based on degrading thinking towards their students, generating negative relationships and interactions, frustration and anger among those involved. In this setting, the indigenous person is assumed to be incapable of moving forward at the same pace of learning as the non-indigenous person, a consequence of the lack of cultural capital (Sukhbaatar & Tarkó, 2022); 5) the school has failed to respond to the educational, social, cultural and linguistic needs of the population it serves, offering decontextualized teaching and learning processes that do not adjust to the socio-cultural and territorial needs of the family and community in which it is located (Milne & Wotherspoon, 2022); 6) the indigenous population and in particular indigenous language-speaking students fall significantly behind non-indigenous students (Manning & Harrison, 2018; Matengu et al., 2019); 7) the alienation of the school from the reality of the indigenous communities shows a low value placed on indigenous people, a lack of respect for traditional authorities, a silencing and negation of the language in the classroom, and the authoritarianism of teachers (Barrios, 2019; Meghan, 2022); 8) the school perpetuates a symbolic and cultural domination of the indigenous population that strips students of their own social, cultural and spiritual frameworks (Arias-Ortega & Quintriqueo, 2021; Delprato, 2019); and 9) the existence of high rates of social and economic vulnerability, accompanied by the social stigma generated by the low value placed on cultural differences (Mallick et al., 2022).

In relation to the above, the question that emerges is: What are the main strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in a Mapuche context from the voices of teachers in La Araucanía, Chile?

Method

The methodology is qualitative, which makes it possible to understand educational and social phenomena, to transform the socio-educational scenarios and practices of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, from the meanings, perceptions, intentions and actions attributed by teachers in La Araucanía, Chile. This enables a twofold process of interpretation. The first involves the researcher-participant relationship because it involves the way in which participants interpret the reality that they socially construct. The second involves the way in which social researchers understand how participants socially construct their realities (Archibald et al., 2019).

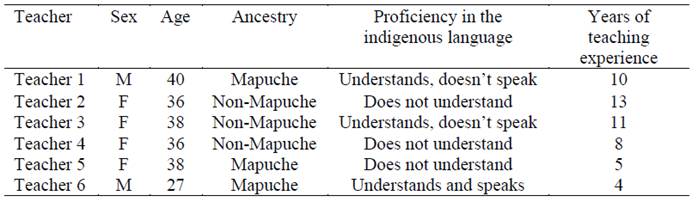

The study context is La Araucanía, Chile, specifically multilevel schools located in the rural Mapuche communities of Padre Las Casas (Arias-Ortega, 2020). The study participants are six teachers, who are described in Table 1.

Inclusion criteria are: 1) municipal and/or private subsidized schools with multilevel classrooms and an enrollment of students with Mapuche and non-Mapuche ancestry; 2) schools located in rural Mapuche communities with more than 20 years of existence in the territory; 3) Mapuche and non-Mapuche teachers with at least 3 years of experience working in the school education system. The participant selection technique is intentional and non-probabilistic, where subjects are selected as typical cases, based on criteria of age, ethnicity, gender, schooling and territorial identity (Arias-Ortega, 2020).

The data collection instrument is the semi-directed interview, which inquired about: 1) the meaning of school and school education; 2) the schooling experience and how this affects the construction of the meaning of school and school education in an indigenous context; and 3) recurrent patterns in the installation of school and school education in a Mapuche context (Arias-Ortega, 2020).

The data analysis technique is content analysis in conjunction with grounded theory (Denzin et al., 2008). Content analysis makes it possible to formulate inferences systematically and objectively, based on specific characteristics of the text (Archibald et al., 2019). Grounded theory allows for the discovery of theories and proposals in direct relationship with the data, through open and axial coding (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

Open coding involved generating codes that emerge from the analysis of the teachers’ testimony based on the subjectivity of the researcher, according to the expressions and language of the participants found in the literal sentences they used during the interview (Archibald et al., 2019). The axial coding involved a comparison of the codes, an active and systematic search for the relationship between the data, which was triangulated with the data emerging from content analysis until reaching theoretical saturation.

The following nomenclature is used to understand the direct quotes from the interviews: “(P8-MI(8:33))” where P is the teacher, 8 is the number assigned to the interview document, M if male or F if female, I identifies if the teacher is indigenous and the numbers in brackets correspond to the line in which the mentioned quote is located in the hermeneutic unit of Atlas Ti.

The scientific rigor criteria considered are: 1) dependability, which ensures that the results represent something true and unambiguous, in which the participants’ responses are independent from the circumstances of the research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018); 2) the credibility that connects the findings based on the interpretations given by the participants to the study object; and 3) reliability, which alludes to the possibility of finding similar results in the event that the research methodology is replicated in similar educational contexts (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). The results obtained are also triangulated with the theoretical background, which enables us to ensure its validity. The ethical safeguards considered informed consent, which stipulates that research participants are participating voluntarily.

Results

The results are organized around a main category called school in an indigenous context and three subcategories associated with the strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context.

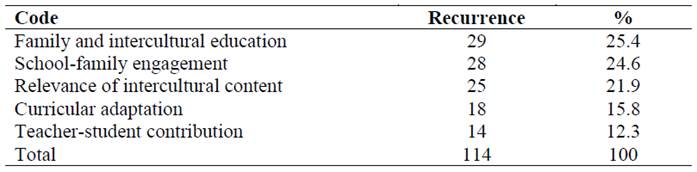

Strengths of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

The strengths of the school in an indigenous context subcategory refers to the positive characteristics that are developed in the educational context and that benefit the teaching and learning processes in the context of schools located in Mapuche communities in La Araucanía. This subcategory has a frequency of 57% of a total of 200 recurrences and is composed of five codes (Table 2).

The family and intercultural education code refers to the contribution of Mapuche families and communities to the incorporation of indigenous knowledge in the pedagogical practices of teachers, with the aim of promoting intercultural education for all children attending school, regardless of whether or not they are indigenous.

One strength of the multilevel school is the possibility of incorporating local and Mapuche knowledge that is present in the social memory of the family and community into the school’s educational processes with the direct involvement of the family. This makes it possible to contextualize and offer teaching and learning processes that respond to the needs of the territory, such as the revitalization of the Mapuche sociocultural identity among new generations, which does not necessarily occur in urban schools. The majority of these schools prioritize hegemonic and monocultural teaching that overlooks specific local knowledge as relevant elements to offer meaningful and culturally relevant learning. Likewise, these schools are notable for the low involvement of the Mapuche family and community, considered a factor that sometimes has a negative impact on the educational processes, due to their low level of schooling. The teachers recognize that it is a strength that in their multilevel schools there is an openness to intercultural teaching. This is reflected in the incorporation of a tutor of traditions in the classroom, who teaches knowledge of socio-religious practices to students, which enables them to go beyond academics and incorporate the spiritual aspect of indigenous children.

One testimony indicates “The school works with the machi (Mapuche spiritual authority), he teaches his culture (in the classroom) to the children, which has made it possible to integrate the community (in the school, the machi celebrates), ceremonies and prayers (in which the family participates)” (P6-MI(6:35)). The testimony shows how the multilevel school promotes involvement with the Mapuche family and community through the incorporation of indigenous epistemic practices into the educational space as a form of progressive decolonization of the ways of knowing accepted in the school environment. This thereby creates spaces to develop teaching and learning processes with local relevance, which grant epistemic validity to Mapuche knowledge in school education.

From the indigenous teacher’s point of view, the incorporation of members of the Mapuche community, who are proficient in their own ways of knowing and knowledge, facilitates the incorporation of Mapuche content into the teaching and learning processes. Likewise, it places value on indigenous aspects in the classroom, which was historically denied in schools and rejected in several urban sectors of the population, as it was assumed that this knowledge is only necessary for the Mapuche person. Incorporating this knowledge together with the family and community in multilevel schools is an opportunity and a strength, since this type of school not only serves indigenous children, but also rural children and children who move from the urban sector. Thus, pedagogical practices in the multilevel school can lead to a greater sensitization of indigenous and non-indigenous people in school education to form intercultural citizens who are respectful of the diversity that characterizes a globalized world, but with social, cultural and territorial relevance.

Regarding the school-family engagement code, teachers indicate that parents participate in the schools, because they have generated and insisted on the need for parents to be involved in the teaching and learning processes of their children, advice that is constantly transmitted to them in parent-teacher meetings. A Mapuche teacher says, “The school and family are getting closer and closer. Parents have even brought up issues with management, the school is becoming more and more familiar with the family” (P1-MI(8:33)). The testimony of the indigenous teacher shows that a school-family engagement helps to draw attention to children’s learning results. It is assumed that the engagement with the family, even if only for complaints, constitutes progress and an opportunity to tear down the mistrust and low involvement of parents in the educational processes. The teachers explain that this is a strength since parents are gradually beginning to come to the school to express their discomfort or concern about their children’s teaching and learning process. However, we note that this conception of school-family engagement comes from a functionalist viewpoint from the school and is based on more administrative aspects in the logic of accountability. We maintain that this functionalist form of engagement is recurrent in urban contexts, but it increases in rural contexts, as a result of the fear and ethnic shame expressed by parents who have low educational levels, which makes them feel that they do not have the authority to support their children’s schooling processes, mainly associated with monocultural educational content. From this perspective, by not considering external and internal factors and needs (for example, low schooling and self-esteem) that may be affecting the collaborative work between both institutions, the school-family engagement could have a negative impact on children’s learning on both an academic and emotional level. This form of engagement would therefore indicate a lack of school-family involvement in the educational act beyond mere academics, in which aspects such as spiritual, emotional, physical and cognitive development are not necessarily being addressed. This raises the urgency of generating joint efforts to integrally achieve school and educational success in the formation of children and youth. School-family engagement ends up taking on a passive role in the conception of their children’s education with respect to the norms, values and contents they receive in their schooling process.

In relation to the relevance of intercultural content code, this refers to the importance given by multilevel schools to indigenous content during the teaching and learning process. The teachers stress the importance of incorporating indigenous content into the classroom as a way of revitalizing the sociocultural identity of the students, to form emotionally strong subjects, with respect and appreciation for their origin, which will allow them to develop in a way that is pertinent to both their own sociocultural context and the hegemonic context. In this regard, a teacher says, “The importance lies in knowing their origins. It is important to know one’s culture, it makes us more involved (...) immersing ourselves in our culture makes us value what we have more and also helps us to project ourselves into the future” (P4-F(4:34)).

The testimony of both indigenous and non-indigenous teachers recognizes that in multilevel schools, developing and strengthening the sociocultural identity of Mapuche students is relevant in developing a sense of belonging to their culture. This assumes an epistemic commitment to both their roots and customs and a further look into their issues to become a relevant actor committed to the needs of the Mapuche family and community. The multilevel school teachers note that this reality of commitment is not necessarily expressed in urban contexts, due to the large number of people in the educational communities, resulting in more depersonalized educational processes. Whereas in multilevel schools, teaching and learning take place in more of a community setting with fewer children. This makes it possible to customize the school education with a socioculturally relevant approach, which contributes to the emotional development of children and young people, favoring their incorporation into global society.

In relation to the curricular adaptation code, this refers to how in their teaching and learning processes, teachers articulate indigenous and school contents in pedagogical practices to respond to the educational needs of students, from a logic of social, cultural and territorial relevance. One testimony says that “the Mapudungun language is integrated as a subject and the Ministry contemplates several hours of its instruction” (P4-F(4:66)). The testimony shows that the articulation of indigenous and school knowledge is mainly associated with the teaching of Mapuche language and culture in the classroom, which is mandatory by the Chilean Ministry of Education. Thus, in the multilevel school in an indigenous context, the incorporation and recognition of Mapuche knowledge in the teaching and learning processes is a strength, because it enables teaching and learning processes that value and consider the ways of knowing and knowledge that students bring with them, in order to offer an education that is contextualized for the territory.

The teacher-student contribution code refers to the engagement between both actors in the educational context. It implies the teachers’ role in both the educational contribution and socioemotional mentoring of their students based on their professional vocation. A teacher says, “We have a lot of conversations in class. Sometimes we stray away from the content and get more into what is under the surface. Conversations about how they are (...), how they feel, they start feeling more comfortable and confident with you” (P5-FI(5:43)). The testimony shows that given the smaller number of students attending multilevel schools, it is possible to generate networks with greater attachment and more tailored work with students and their families, which is expressed in a horizontal treatment, through socioemotional mentoring. This aspect of the teacher-student relationship enables a healthy school coexistence and decreases the dropout rate of indigenous students.

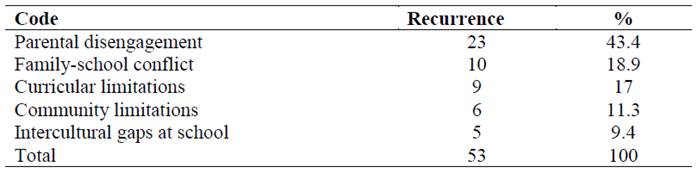

Limitations of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

The limitations of the multilevel school in an indigenous context subcategory refers to obstacles that interfere with the development of teaching and learning processes. This subcategory has a frequency of 26.5% of a total of 200 recurrences and is composed of five codes (Table 3).

The parental disengagement code refers to the lack of parental commitment and concern for their children’s school education. In the teachers’ words, this is expressed in the responsibility parents attribute to the faculty as solely responsible for the education of students. In this regard, one testimony stated that “teaching is supposed to be (...) fifty (percent) at school, fifty at home, but children only study at school. At home parents often don’t even check their backpacks” (P5-FI(5:33)). In multilevel school contexts, this perception of abandonment of parental responsibilities could be explained by the fact that parents assume that they are incapable of collaborating with their children’s school process, mainly due to their lack of knowledge of the school content. This generates discomfort among teachers, who then feel that they are the only ones responsible for this task, which they recognize is not the case, since family engagement should go beyond academics. Likewise, teachers perceive that parents delegate other activities and responsibilities to students (e.g., animal care), which interferes with their teaching and learning process at school. One testimony indicates, “Children help, (...) they are given other responsibilities, anything but homework, homework is the last priority. Many children go to school with the same clothes they wore the day before” (P4-F(5:35)) The limitations of the multilevel school also notably include the teachers’ prejudice towards indigenous children and their families, by mentioning that students attend classes with the same clothes from the previous day. They do not stop to ask whether this could be the result of the family’s economic needs and not specifically the parents’ lack of concern for the care of their children. This raises the need for multilevel schools to be aware of the population they serve, since historically these types of schools are characterized by the economic and social vulnerability of the children who attend them, as these are the sectors with the highest poverty rates in the country. It challenges them to be strategic in approaching the learning contents, promoting a comprehensive formation in which the learning acquired at home is linked to pedagogical contents, thus favoring family-school engagement.

The family-school conflict code refers to problematic situations and/or tension between both educational actors. One testimony indicates, “There are families that don’t interfere one way or another, I don’t want to generalize (...) there are parents who (...) instead of making it easier for their children to do their homework, they do it for them so that (...) the teacher can see that «my child did their homework»” (P4-F(4:42)). The testimony shows the conflicts and unease that the parents’ attitude generates in the teachers in terms of collaboration in their children’s education, wherein rather than getting involved in the learning activities, the parents find it faster to just do the activity themselves. This prevents students from acquiring and developing skills and knowledge, since they have no awareness of the knowledge they are learning. Likewise, this testimony reveals the power relations and prejudices that exist towards the family, where the teacher’s perception is to unidirectionally assume without evidence that parents do their children’s homework. This is further exacerbated if we consider the low educational levels of parents in indigenous territories, who recognize that their involvement in teaching is limited by their lack of knowledge of school content. Therefore, there is an implicit assumption that indigenous children ‘would not be able’ to undertake the activities on their own, which in multilevel schools would increase power relations and prejudices towards the Mapuche people.

The curricular limitations code refers to the scarce incorporation of indigenous content in the different teaching subjects, which does not promote an adequate contextualization of school contents with the Mapuche culture on both a national and regional level. This problem is further exacerbated in multilevel schools that must also struggle with multigrade teaching, where children of different ages share a classroom. Although there are general limitations on a national level, the curricular limitations are even greater in multilevel schools that have to overcome economic shortages, multigrade teaching, poor infrastructure, lack of teaching staff, among others. In addition, these limitations of the monocultural curriculum are combined with a lack of knowledge among teachers regarding indigenous knowledge as a result of their western Eurocentric pre-service teacher education, which denies the epistemic validity of indigenous knowledge. One testimony indicates “change the curriculum, focus more on cultures (...). For example, how are you going to integrate an Aymara, Mapuche or Rapa Nui child, if the child speaks their language and you don’t... you don’t know anything about their culture” (P5-FI(6:68)). From this account we can infer that there is little teacher training with respect to the indigenous contents of the area in which they develop educational practices, which limits the ability to provide a relevant and contextualized education. Likewise, the rigidity of the school curriculum hinders the mainstreaming of indigenous knowledge in other disciplinary areas in the classroom.

The community limitations code refers to resistance from Mapuche communities that hinders relations between the school and the community. From the teachers’ testimony, this is manifested in the parents’ mistrust of the school, which is expressed in the refusal of Mapuche families and communities to contribute their own cultural knowledge, practices and customs to enrich the teaching and learning processes. A teacher says, “(Jealous) I mean that they want to keep their learning, their culture, their customs to themselves and leave it in that core, they don’t want them to mix with the wigka” (P1-F(8:56)). According to this account, there is mistrust on the part of the Mapuche communities regarding the transmission of cultural customs and traditions. This translates into a limitation in the development of intercultural learning, both on the part of students and the educational community as a whole. This could also be explained from the perspective of parents, who have historically had a relationship of mistrust with the school, as a result of the history of this institution in indigenous territory. This has left its mark on parents and indigenous elders who experienced practices of physical punishment, discrimination and racism from educational actors who sought a cultural genocide of indigenous ways of knowing in their spaces. These community limitations highlight the reciprocal resistance between the two institutions to establish a true intercultural dialogue that would achieve schooling and educational success for all students.

The intercultural gaps at school code refers to the limitations of trained personnel for the implementation of intercultural education. One testimony says “we lack culture in general and the only one in charge of teaching that culture is the Mapudungun teacher or the Mapudungun-speaking teacher” (P2-F(4:33)). This account identifies the lack of professionals with intercultural competencies, such as proficiency in the Mapuche language, which is an obstacle to the teaching and preservation of cultural frameworks at school. This affects the education of new generations, impacting the psychological well-being of indigenous students and influencing the construction of their sociocultural identity. This problem must be urgently addressed in multilevel schools, since they have the opportunity to involve the family and indigenous elders in teaching practices, as they are part of Mapuche communities where the indigenous way of knowing is still alive. Therefore, the family and the community needs to become a living laboratory of epistemic ways of knowing and knowledge in order to decolonize school education from the bottom up, i.e., starting with the family and the community and permeating the school system.

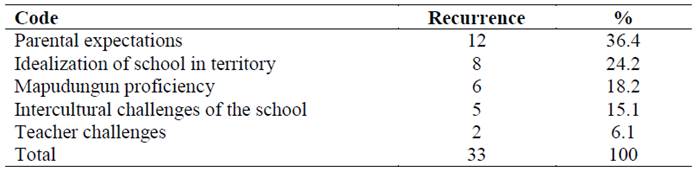

Challenges of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

This subcategory refers to aspects that need to be improved in the teaching and learning processes. It obtained a frequency of 16.5% of a total of 200 recurrences and is composed of five codes (Table 4).

The parental expectations code is associated with the future projection that parents have regarding their children’s school education. A teacher says, “Some (parents) want their children to go to university (...). Many dream of their children becoming professionals because there are none (professionals) in their families” (P5-FI(4:25)). The testimony shows that parents are interested in their children’s education and the continuity of their studies, hoping that their children can achieve an educational level that they themselves did not reach. In other cases, teachers point out that “they are satisfied that their children know how to read and write so that they can help them with their jobs” (P4-F(4:26)). From this account we can infer that in indigenous contexts there are aspects that condition parents’ expectations for the continuity of their children’s studies, for example, the economic aspect or the literacy level of the family. They may be satisfied that their children learn to read and write, because it will help them to make an immediate contribution to the household economy, and they may fail to see the possibilities that the continuity of studies and the acquisition of a professional degree could bring for them and their family.

The idealization of school in indigenous territory code refers to the ideal school from the teachers’ perspective. It incorporates cross-cultural characteristics such as cultural symbols and a school curriculum that responds to the needs of the Mapuche communities. One testimony indicates that “the school should have aspects such as two flags, the national flag and the Mapuche flag, because they are part of the Mapuche culture. It should focus on their traditions, on the celebration of their traditions” (P5-FI(5:40)). This indicates that multilevel schools in the indigenous territory should incorporate symbols and celebrations associated with Mapuche culture that promote a sense of belonging so that students, families and communities can identify with the school and their territory. Another testimony adds that “the school curriculum should be intercultural, focused on various cultures, not just the traditional curriculum that we have now” (P6-MI(6:66)). We can infer the challenge of incorporating a relevant intercultural school curriculum that connects with the real needs of the area in which the school is immersed in order to provide a quality education with cultural relevance.

The Mapudungun proficiency code refers to proficiency in the vernacular language by teachers working in an indigenous context. A testimony mentions “I am unfamiliar with it because I never had Mapudungun classes, so I don’t know how to pronounce a lot of things (...) I can tell you a couple of words, but I don’t use them in context or in everyday life” (P3-F(4:31)). It is evident that there is low proficiency in Mapudungun, which becomes a barrier to the preservation of the indigenous language and an obstacle to understanding the worldview of the students’ culture. It also constitutes an obstacle in their relationship with family members and the community, since they won’t be able to achieve a communication where the message transmitted is truly understood.

The intercultural challenges of the school code refers to proposals made by the educational community to improve intercultural education, both in terms of school content and the inclusion of new subjects. A teacher says that “language also has to do with spirituality and care for the environment. The indigenous culture takes special care of its environment” (P6-MI(6:27)). The testimony shows the importance of considering elements of the Mapuche worldview, such as the relevance of the environment. Teachers find it challenging to get involved with the Mapuche culture, since they generally are not from the territory and have a limited understanding of cultural elements. This poses a challenge for the relationship with students, families and the community.

Finally, the teacher challenges code refers to the teachers’ commitment to improve their professional competencies in order to provide a quality, up-to-date education to students. In relation to this code, one testimony indicates that “as a teacher I am always learning, always taking more courses, always learning. I think that you never stop learning until the day you die” (P1-MI(1:93)). Teachers are committed to their own lifelong learning and training for their professional development, and to acquiring the tools that respond to the needs of the educational and cultural reality of the territory in which the school is located, to provide an education with an intercultural perspective.

Discussion and conclusions

The research results allow us to confirm that schools in general, and the multilevel school in particular, located in an indigenous context, have not been able to establish a real connection with the Mapuche family and community. This relationship is relegated to administrative aspects rather than an involvement in the teaching and learning process of indigenous and school content. This reality is consistent with the difficulties of engagement that occur in other indigenous territories, such as New Zealand, Mexico and Colombia, where it is reported that there is a distant and even hostile relationship between the family and the school in an indigenous context (Archibald et al., 2019; Delprato, 2019; Harcourt, 2020). This could be explained by the mistrust that families have towards the multilevel school, which is the same school system that they underwent in their territories, which has left them with psychological traumas as a result of the systemic racism towards the indigenous community. In general, multilevel schools installed in indigenous territories, from colonial times to the present, have not abandoned this logic of standardization of children, making assumptions from a paternalistic approach that they lack cognitive capacity, and wielding an implicit power that their professional education has attributed to them over families and indigenous communities.

Even when teachers express good intentions and a willingness to foster trust-based relationships with parents to ensure students’ success in school and education, this does not come through in teaching and learning practices. For example, prejudices towards indigenous people are recurrent in the discourse of non-indigenous teachers, who maintain that there is a lack of interest on the part of the Mapuche family in the education of their children, and that there are practices of personal neglect of indigenous children. This prejudiced view contradicts the position of the indigenous teacher, who affirms that families try to get involved in the educational processes of their children, recognizing that factors such as poverty or low schooling could have an impact on an adequate educational relationship. Some testimonies even justify that this family-school engagement may be strained by the marks left by the school on parents and grandparents from when they underwent their formal schooling process.

From the voices of indigenous and non-indigenous teachers, it is of vital importance that the Mapuche family and community be involved in the processes of intercultural teaching and learning in school education. The school should incorporate indigenous knowledge and skills in articulation with the school curriculum in order to offer a socially and culturally relevant school education. This would make it possible to reverse the historical characteristics of the school in indigenous territory that has systematically erased indigenous ways of knowing and knowledge from the teaching and learning processes (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022; Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Dillon et al., 2022). According to Meghan (2022), the school in an indigenous context should contribute to an intercultural coexistence between people and communities that recognize their differences in a dialogue without prejudice or exclusion in order to co-construct an educational space with meaning for the family and community. This makes it possible to reverse the visible prejudice of teachers towards indigenous families and communities, attributing them with a sense of detachment and responsibility for the teaching and learning process of their children.

In this sense, the multilevel school in indigenous territory has the possibility and opportunity to strengthen the sociocultural identity of Mapuche children, due to its location in the territory that maintains their own worldview and cosmogony. This would mark the first steps towards an intercultural education for the formation of new generations of indigenous and non-indigenous children (Mallick et al., 2022). However, this is not an easy pedagogical process, since the traditional school curriculum is based on a legal framework that excludes intercultural content with local relevance. However, in multilevel schools it is more feasible to contextualize teaching, due to the living laboratories of indigenous ways of knowing and knowledge in the territory, unlike the situation in urban contexts. We argue that the teachers’ lack of knowledge of indigenous ways of knowing limits their incorporation in the classroom, affecting the relationship with the family and community environment, as a result of the disconnect between the educational needs and purposes of the school and the family (Arias-Ortega, 2020). The multilevel school in a Mapuche context should provide spaces to achieve greater engagement with family and community actors in order to strengthen the incorporation of indigenous knowledge in school processes. In addition, this family-school-community engagement would allow the formation of emotionally strong individuals with a high degree of sociocultural belonging, which also contributes to the development of the individual and collective well-being of the Mapuche family and community. From this perspective, the school in an indigenous context should favor instances that allow for a healthy relationship and coexistence between the community, the family and the school in order to reduce the mistrust between the three groups. This reality raises the need and urgency to generate spaces for engagement and dialogue between actors from the school, the family and the community of the students who attend it. Likewise, it is urgent for the school to make a commitment to revitalizing the sociocultural identity of indigenous and non-indigenous students in the teaching and learning processes in order to form emotionally strong subjects with a high self-worth, favoring their school and educational success in their formal schooling process. This would make it possible to promote the development of a school curriculum that adapts to the needs of the school located in a Mapuche context in order to offer teaching and learning processes with territorial and cultural adaptation that are meaningful for students and their families, and to improve the intercultural competencies of teachers to attend to the diversity of indigenous and non-indigenous students.

REFERENCES

Archibald, J., Lee-Morga, J. B. J., & De Santolo, J. (Eds.). (2019). Decolonizing Research Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. Zed Books. [ Links ]

Arias-Ortega, K. & Ortiz, E. (2022). Intervenciones educativas interculturales en contextos indígenas: aportes a la descolonización de la educación escolar. Revista Meta: Avaliação, 14(42), 193-217. [ Links ]

Arias-Ortega, K. & Quintriqueo, S. (2021). Relación educativa entre profesor y educador tradicional en la Educación Intercultural Bilingüe. Revista electrónica de investigación educativa, 23, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2021.23.e05.2847 [ Links ]

Arias-Ortega, K. (2020). Sentido de la escuela y la educación escolar en contexto indígena. Bases para una relación educativa intercultural. Proyecto Fondecyt de Iniciación 2020-2023. [ Links ]

Barrios, B. (2019). Educación intercultural: ¿Un espacio de encuentro o un campo de luchas? Revista Nuestra América, 7(14), 102-127. [ Links ]

Commission de Vérité et Réconciliation du Canada. (2015). Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir: Sommaire du rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP. [ Links ]

Delprato, M. (2019). Parental education expectations and achievement for Indigenous students in Latin America: Evidence from TERCE learning survey. International Journal of Educational Development, 65, 10-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.12.004 [ Links ]

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2018). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. SAGE. [ Links ]

Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., & Smith, L. (2008). Handbook of critical indigenous methodologies. SAGE. [ Links ]

Dillon, A., Craven, R., Guo, J., Yeung, A., Mooney, J., Franklin, A., & Brockman, R. (2022). Boarding schools: A longitudinal examination of Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous boarders’ and non-boarders’ wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal, 48(4), 751-770. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3792 [ Links ]

EagleWoman, A., Terry, D. J., Petrulo, L., Clarkson, G., Levasseur, A., Sixkiller, L. R., & Rice, J. (2022). Storytelling and Truth-Telling: Personal Reflections on the Native American Experience in Law Schools. Mitchell Hamline Law Review, 48(3), 1-9. [ Links ]

Harcourt, M. (2020). Teaching and learning New Zealand's difficult history of colonisation in secondary school contexts (Tesis de doctoral, Victoria University of Wellington). http://hdl.handle.net/10063/9109 [ Links ]

Mallick, B., Popy, F. B., & Yesmin, F. (2022). Awareness of Tribal Parents for Enrolling Their Children in Primary Education: Chittagong Hill Tracks. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 9(3), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.93.11905 [ Links ]

Manning, R. & Harrison, N. (2018). Narrativas de lugar y tierra: enseñanza de historias indígenas en la formación de profesores de Australia y Nueva Zelanda. Revista Australiana de Formación del Profesorado, 43(9). http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n9.4 [ Links ]

Matengu, M., Korkeamäki, R., & Cleghorn, A. (2019). Conceptualizing meaningful education: The voices of indigenous parents of young children. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 22, 100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.05.007 [ Links ]

Meghan, S. (2022) Deficit discourses and teachers’ work: the case of an early career teacher in a remote Indigenous school. Critical Studies in Education, 63(1), 64-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1650383 [ Links ]

Milne, E. & Wotherspoon, T. (2022). Student, parent, and teacher perspectives on reconciliation-related school reforms. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 17(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2022.2042803 [ Links ]

Sabzalian, L. (2019). Indigenous Children´s Survivance in Public Schoools. Routledge. [ Links ]

Sukhbaatar, B. & Tarkó, K. (2022). Teachers’ experiences in communicating with pastoralist parents in rural Mongolia: implications for teacher education and school policy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 50(1), 34-50, https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2020.1818056 [ Links ]

Funding: This research was possible thanks to the Fondecyt de Iniciación project No. 11200306, financed by the Chilean National Research and Development Agency.

How to cite: Arias-Ortega, K., Díaz Alvarado, N., Catrimilla Castillo, D., & Saldías Soto, M. J. (2023). Multilevel schools in an indigenous context: strengths, limitations and challenges from the perspective of teachers in La Araucanía. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2841. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2841

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. K. A.-O. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; N. D. A. in a, b, c, d; D. C. C. in a, b, c, d; M. J. S. S. in a, b, c, d.

Received: March 01, 2022; Accepted: March 02, 2023

texto em

texto em