Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.1 Montevideo 2023 Epub 01-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2583

Original Articles

Coparenting as a mediator between mothers’ emotion dysregulation and the perception of adolescents’ emotion regulation

1 Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brasil, luiza.dce@gmail.com

2 Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brasil

Research on the development of emotion regulation in childhood and adolescence suggests that the etiology of the phenomenon is multifactorial and that it is necessary to investigate the broader contextual aspects. Coparenting is a contextual variable that has been associated with outcomes in children and may be related to emotional regulation. The aim of this study was to test a structural model of direct and indirect relationship between mothers' emotional dysregulation and the perception of their adolescent children’s emotional regulation, evaluating the mediating role of coparenting. This is a quantitative, cross-sectional and explanatory study conducted with 210 mothers of adolescents (M = 15.59, SD = 1.39 years old). The sociodemographic questionnaire, the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC) and the Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA) were administered online. Descriptive analyses, correlational analysis and structural modeling equations were conducted. The interactional model points to the partial mediating effect of coparenting in this relationship, as well as the indirect effect of the mothers' emotion dysregulation on the emotional regulation of the adolescents. The results also pointed out that the mothers' emotional dysregulation seems to have a detrimental impact on coparental cooperation. These results are important factors to be considered in the clinical context when working with adolescence and their families.

Keywords: emotional regulation; emotional dysregulation; coparenting; adolescents; mothers

Pesquisas na área do desenvolvimento da regulação emocional sobre a infância e adolescência sugerem que a etiologia do fenômeno é multifatorial e que é necessário investigar aspectos contextuais relacionados. A coparentalidade é uma variável contextual que vem sendo associada a desfechos nos filhos, podendo ter relação com a regulação emocional. O objetivo desse estudo foi testar um modelo estrutural de relação direta e indireta entre desregulação emocional de mães e a percepção da regulação emocional de seus filhos adolescentes, avaliando o papel mediador da coparentalidade. Trata-se de um estudo quantitativo, transversal e explicativo realizado com 210 mães de adolescentes (M = 15,59, DP = 1,39 anos). Para isso foram utilizados o questionário sociodemográfico, o Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), o Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC) e o Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA) com aplicação online. Foram realizadas análises descritivas, análise correlacional e modelagem de equações estruturais. O modelo interacional aponta para o efeito mediador parcial da coparentalidade nessa relação, bem como efeito indireto da desregulação das mães para a regulação emocional dos adolescentes. Os resultados ainda apontaram que a desregulação emocional das mães parece ter um impacto prejudicial na cooperação coparental. Esses resultados indicam importantes fatores a serem considerados no âmbito clínico nas intervenções com adolescentes e suas famílias.

Palavras-chave: regulação emocional; desregulação emocional; coparentalidade; adolescentes; mães

La investigación sobre el desarrollo de la regulación emocional en la infancia y la adolescencia sugiere que la etiología del fenómeno es multifactorial y que es necesario investigar aspectos contextuales relacionados. La crianza conjunta es una variable contextual que se ha asociado con los resultados en los niños y puede estar relacionada con la regulación emocional. El objetivo de este estudio fue probar un modelo estructural de relación directa e indirecta entre la desregulación emocional de las madres y la percepción de la regulación emocional de sus hijos adolescentes, evaluando el papel mediador de la coparentalidad. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo, transversal y explicativo realizado con 210 madres de adolescentes (M = 15.59, DE = 1.39 años). Para ello se utilizó un cuestionario sociodemográfico, la Escala de Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional (DERS), la Lista de Verificación de Regulación Emocional (ERC) y el Inventario Coparental de Padres y Adolescentes (CI-PA) con aplicación en línea. Se realizaron análisis descriptivos, análisis correlacionales y modelado de ecuaciones estructurales. El modelo interaccional apunta al efecto mediador parcial de la coparentalidad en esta relación, así como el efecto indirecto de la desregulación de las madres para la regulación emocional de los adolescentes. Los resultados también señalaron que la desregulación emocional de las madres parece tener un impacto perjudicial en la cooperación coparental. Estos resultados indican factores importantes a considerar a nivel clínico en intervenciones con adolescentes y sus familias.

Palabras clave: regulación emocional; desregulación emocional; coparentalidad; adolescentes; madres

In the last two decades, the interest in understanding adolescence as a critical period for the development of emotion regulation has increased (Crandall et al., 2016; Machado & Mosmann, 2019). Regulating emotions is an essential human development skill for maintaining successful relationships with peers (Blair et al., 2016) and family (Reindl et al., 2018), academic functioning (Kwon et al., 2017), well-being (Williams et al., 2018) and mental health (Inwood & Ferrari, 2018).

Emotional regulation involves having strategies to maintain, increase or decrease one or more components of the emotional response. It is a process of modulation, occurrence, duration, and intensity of internal states (positive and negative) and physiological processes related to emotion (Morris et al., 2017). The ability to regulate emotions implies influencing the emotional experience, according to the situation, timing, and emotional valence (McRae & Gross, 2020), in order to achieve the desired affective states and achieve adaptive results to deal with everyday situations.

On the other hand, the difficulty in emotion regulation (deficits in emotion regulation or emotional dysregulation) occurs through a dynamic process (D'Agostino et al., 2017) of interaction between difficulty in awareness, comprehension, or modulation of emotion (Bjureberg et al., 2016) and learning history of dysfunctional strategies to manage emotions (Bariola et al., 2011) throughout development (D'Agostino et al., 2017). In this sense, difficulties in emotion regulation are related to manifestations of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Machado & Mosmann, 2019), various mental disorders (D'Agostino et al., 2017) and personality disorders (D'Agostino et al., 2017).

Because it is a relational variable, research on the development of emotional regulation from childhood to adolescence suggests that the etiology of the phenomenon is multifactorial. The main focus of research is related to the regulation of one’s own emotions (intrinsic regulation), but there has been a growing interest towards the regulation of other people and the context in which people are located (extrinsic regulation) (McRae & Gross, 2020).

Context, as extrinsic regulation, has gained strong empirical support as a contributor to the development of emotion regulation (Li et al., 2019). Studies about social factors suggested that interactions with mothers (Perry et al., 2020), fathers (Li et al., 2019), teachers (Pallini et al., 2019) and peers (Cui et al., 2020) were related to the development of emotional regulation in children.

Although the emotional regulation of both parents is crucial in the development of children's emotions, many studies have focused their attention on the mother's role and its impact on adolescents (Cheung et al., 2020; Crandall et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2020). There is a vast literature connecting mothers' difficulty in emotion regulation with symptomatic outcomes in children, such as internalizing symptoms in adolescent children (Cheung et al., 2020), dissociation in children (Lewis et al., 2020) and difficulty in emotion regulation (Cheung et al., 2020). Thus, mothers with emotional regulation difficulties have an important impact on the emotional regulation of their adolescent children. A longitudinal study (Cheung et al., 2020) that investigated the emotion regulation difficulties experienced by 386 Hong Kong families including mothers, fathers and adolescents in two stages (over 12 months) discovered that only the mothers' emotion regulation difficulties were a predictor of difficulties in emotion regulation in the children, and even in the parents longitudinally, while the difficulty in emotion regulation of the parents had no influence on the emotions of the mothers or children in this study.

It is already a consensus in the literature that children tend to imitate or internalize the ways in which their mothers struggle with regulating emotions via modeling or social learning mechanisms (Bariola et al., 2011) throughout development. However, when analyzing studies about the development of emotion regulation, we find other aspects that contribute to regulation or difficulty in regulating children's emotions, such as parental socialization (Szkody et al., 2020), family climate (Morris et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2007), conjugality (Morris et al., 2007) and parental support (Karaer & Akdemir, 2019).

Although studies on emotional regulation of children and family relationships have advanced in recent years, authors in the field suggest that researchers explore interrelationships between family systems and subsystems (Gallegos et al., 2017; Thomassin et al., 2017). Thus, family and relational variables need to be investigated as mediating factors between the mothers' difficulty in emotional regulation and the development of emotional regulation in their adolescent children. A construct that is associated with relational aspects such as parenting, family climate and conjugality is coparenting (Mosmann & Wagner, 2008; Mosmann et al., 2018).

Coparenting is theoretically conceived as the intervening subsystem between the marital relationship and the relationships between parents and children (Mosmann et al., 2017), since the level of collaboration between the parental couple can influence the way how they interact with the children and perform their parental tasks. A scope review that discusses 20 years of research on coparenting indicates that this construct is related to the interaction in which the coparenting pair coordinates each one's parenting. The main findings of this review indicate that the characteristics of each of the coparenting duo, the state of the relationship (romantic), the context in which the family lives and the characteristics of the child interfere with the coparenting quality. On the other hand, the review also indicates that positive coparenting is related to better marital relationships and positive development of children (Mosmann et al., 2017).

A theoretical model (Margolin et al., 2001) proposes that coparenting has three dimensions: cooperation, conflict, and triangulation. The cooperation dimension (positive dimension) is related to support, validation, respect and understanding that the other caregiver is emotionally capable of exercising parental functions, the conflict dimension (negative dimension) refers to the amount, frequency and severity of disagreements or discussions about the children's education, and the triangulation (negative dimension) is related to a distortion of the limits between the coparental and father/mother-child subsystems, in which one of the caregivers establishes a coalition with the child, excluding or weakening the other figure parental.

A systematic review from 2017 (Costa et al., 2017), with the objective of analyzing the methodological characteristics, objectives and results of empirical studies on coparenting, investigated 29 studies from 2007 to 2016 in English, Spanish and Portuguese. In this study, it was possible to verify that the scientific literature has focused on identifying possible associations between characteristics of the children's behavior and the exercise of coparenting, as well as the impact of coparenting on the family climate. This indicates that coparenting may function as a link between parenting and outcomes for children's emotional and behavioral problems.

Many studies on coparenting have associated this phenomenon with outcomes in children. For example, the negative dimensions (conflict and triangulation) have been associated with internalizing and externalizing disorders (Mosmann et al., 2018), social anxiety behaviors (Riina et al., 2020) and mild antisocial behaviors (Koch et al., 2020). On the other hand, cooperation has been linked to children's social competence (Barnett et al., 2011) and better self-esteem (Macie & Stolberg, 2003).

Some studies that evaluate coparenting and emotional regulation indicate the importance of the association. The first study (Machado & Mosmann, 2019) evaluated the emotional regulation of 229 Brazilian adolescents (11 to 18 years old) as a mediator between the negative dimensions of coparenting and internalizing symptoms from their perception. The results revealed that emotional regulation plays a decisive role in the development of internalizing symptoms in the context of coparenting difficulties. Another study (Thomassin et al., 2017), carried out in the United States, sought to examine the role of coparental affection in children's emotional regulation difficulties in 51 mother-father-child triads (children aged between 7 and 12 years). The study also investigated whether this association mediated the link between parental depressive symptoms and children's emotional regulation. The triads were recorded talking about sad and happy situations. This study verified that the congruence of positive affect from the parents during the discussion about the emotion of sadness predicted emotional dysregulation in the children, both due to the negative affect of the child and the punitive reactions from the parents. Another study (Qian et al., 2020) that carried out a mediation model focusing on family functioning and marital satisfaction to understand the relationship between coparenting and emotional regulation of children indicated that the coparenting relationship is positively associated with emotional regulation of children. However, these studies do not identify the relationships between mothers' emotional regulation and the role of coparenting as part of the development of emotional regulation in children, so the nature of these connections has not yet been fully elucidated.

In this sense, studies indicate as a limitation the need to understand how individual variables contribute to coparenting (Campbell, 2022; Mosmann et al., 2018). Although there is some evidence of the relationship between coparenting and symptomatic outcomes in children, there is a gap in understanding in regards to the dynamics of mothers' difficulty in emotional regulation, the dimensions of coparenting (contextual variable) and emotional regulation of children. It is possible to measure this interaction through interactional models such as Structural Equation Modeling. Therefore, this study aimed to test a structural model of direct and indirect relationship between emotional dysregulation of mothers and the perception of the emotional regulation of their children, evaluating the mediating role of coparenting (triangulation, conflict, and cooperation).

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a quantitative, cross-sectional, and explanatory study (Creswell, 2010). Quantitative approaches aim at the numerical presentation of data, with the goal of describing, explaining and/or predicting a phenomenon (Sabadini et al., 2009). The explanatory character aims to deepen the knowledge of reality in order to explain factors that contribute to the occurrence of a certain phenomenon (Gil, 2010).

Sample

The study included 210 mothers of adolescents, aged between 30 and 58 years (M = 43.19 and SD = 6.93). Inclusion criteria were being mothers of adolescents aged between 14 and 18 years (M = 15.59 and SD = 1.39) and being in a coparental dyad, in which caregivers did not necessarily need to be parents or married, but two people exercising parental care. The number of participants was determined according to the sample calculation proposed by Hair et al. (2010), in which 200 is the minimum number of participants for the calculation of structural equation modeling.

Among the participants, the highest concentration of the sample (28.1 %) reported that they had completed postgraduate studies (n = 59), followed by 23.3 % (n = 49) who had completed higher education, 18.1 % (n = 38) who had completed high school, 13.3 % (n = 28) with incomplete higher education, 5.2% (n = 11) with incomplete high school education, 3.3 % (n = 7) with incomplete graduate school education, 3.3 % (n = 7) with technical education, 3.3 % (n = 7) with incomplete primary education, and 1.9 % (n = 4) with complete elementary education. As for the income of the participants, 51 % (n = 107) received from 1 to 4 minimum wages, 21.4 % (n = 45) received from 4 to 6 minimum wages, 13.3 % (n = 28) reported not having a personal income, 7.1 % (n = 15) earned from 7 to 9 minimum wages, 5.2 % (n = 11) earned from 10 to 15 minimum wages and 1.9 % (n = 4) of sample earned 16 or more minimum wages.

Of this sample, 17.1 % of the participants reported being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. Anxiety disorders (Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Panic Disorder) and mood disorders (Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder) were mentioned. Regarding the person who coparents with the mother, most participants (82.9 %) mentioned the father or partner (n = 174), while 12.9 % reported grandparents (n = 27), 1.9 % mentioned children (n = 4), 1.9 % mentioned other relatives (n = 4), and 0.5 % mentioned friends (n = 1) as the co-parenting dyad.

Instruments

Sociodemographic questionnaire. Constructed for this study, it has 15 questions, seeking to obtain information such as: gender, age, education, number of children, age of children, etc.

Difficulty of emotional regulation of Mothers. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The DERS is a 36-item self-report scale that measures difficulties in emotion regulation. The present study used the short version (Bjureberg et al., 2016) in which the instrument consists of 16 items on a 5-point Likert scale, (1: almost never applies to me and 5: almost always applies to me). The scale assesses emotion regulation difficulties through the following dimensions: non-acceptance of negative emotions (3 items), inability to engage in goal-directed behavior when experiencing negative emotions (3 items), problems controlling impulsive behavior when experiencing negative emotions (3 items), limited access to emotion regulation strategies (5 items) and lack of emotional clarity (2 items). DERS-16 already has evidence of validity for the adult public in Brazil (Miguel et al., 2017), as it presented good rates of psychometric properties, with Cronbach's alpha values > .080 and Confirmatory Factor Analysis rates were RMSEA .096, NNFI .96, CFI .97 and SRMR .054.

Emotional regulation of adolescents. The emotional regulation variable of adolescent children was measured by adapting the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1995). The original version seeks to investigate emotional regulation of children (designed for children aged 3 to 12 years), based on the perception of parents. It consists of 24 items on a four-point Likert scale according to the frequency of the behavior (1: never to 4: almost always). The items are distributed in two scales: Emotional Regulation (ER) and Emotional Lability/Negativity (L/N). The Brazilian adaptation (Reis et al., 2016) of the original scale, which presented assumptions for exploratory factor analysis were adequate and the bifactorial solution (RE and L/N) was indicated, explaining 57 % of the variance (L/N α = .77 and RE α = .73). Lability/Negativity scores must be reversed for correction.

For this study, an adaptation was proposed for adolescents, involving several steps to analyze the validity and reliability of the instrument. These steps included: I) scale adaptation; II) content analysis; III) exploratory factor analysis; and IV) confirmatory factor analysis. The Content Validity Coefficient (CVCt), which involved content analysis performed by three expert judges in the field, yielded a value of 0.936921 for the scale, indicating an acceptable level of agreement among the judges regarding the clarity of language and practical relevance of the scale. The Cronbach's Alpha coefficient for the scale in the exploratory factor analysis was .85. The indices for the confirmatory factor analysis were as follows: CMIN/DF 1.53, CFI .90, RMSEA .05, and SRMR .04.

Dimensions of coparenting. The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents CI-PA. The parent version (Teubert & Pinquart, 2011) consists of two parts, each of which assesses three subscales: cooperation, conflict, and triangulation. In the first part, caregivers report on coparenting at the dyadic level (dyad assessment), for example, “My partner and I agreed to fulfill our child's wishes and demands”. The second part evaluates the caregiver's perception of their partner's contribution to coparenting (evaluation of the other caregiver), for example, “My partner informs me about important events related to our child”. In this study, only the first part was used, reporting coparenting at a dyadic level. Each CI-PA item is rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (completely true) to 4 (not true at all). The Brazilian version (manuscript in preparation) showed good rates of psychometric properties, with the Cronbach's alpha values for Coparental Cooperation (α = .89), Coparental Conflict (α = .76) and Coparental Triangulation (α = .79). Confirmatory factor analysis of this scale showed RMSEA indices of .60, SRMR .50 and CFI .96 for the part that evaluates the dyad.

Ethical and data collection procedures

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos. The participants were selected by convenience criteria, with the Snowball method (Flick, 2009), through social networks such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram. The application was carried out online, through Google Forms. All participants agreed to participate in the study by indicating yes on the Free and Informed Consent Form of the online questionnaire. Confidentiality and autonomy were ensured in case they no longer wanted to take part in the research.

Data analysis

The collected data were entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 22.0 software (IBM SPSS) and the significance level adopted was p ≤ 0.05. Descriptive analyses were carried out in order to know the behavior of the study variables and correlation analysis using the Spearman Coefficient, to verify the existence of a correlation between the sociodemographic variables, the dimensions of coparenting and the emotional dysregulation of mothers and the emotional regulation of the teenage children.

To test the proposed interaction model, data were entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Analysis of Moment Structures 2.0 software (IBM SPSS AMOS). Structural equation modeling was carried out to analyze the explanatory relationships and the predictive value of emotional dysregulation of mothers and the mediating role of the dimensions of coparenting simultaneously, analyzing the direct and indirect relationships with the emotional regulation of adolescent children, with estimation through the Maximum Likelihood method. For the evaluation of model fit, the following indices were used: absolute measures (chi-square/degrees of freedom (χ²/df), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)) and incremental fit measure (Comparative Fit Index (CFI)). Indicators of good model fit refer to χ²/df values below 5, RMSEA values smaller than .10 and CFI values greater than .90 (Hair et al., 2010).

Results

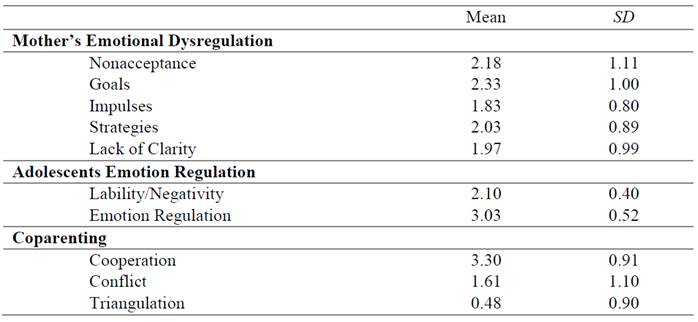

Descriptive analysis and correlation between factors

Descriptive statistics were performed with the variables examined in this study, emotional dysregulation of mothers with the following dimensions: non-acceptance of negative emotions (Non Acceptance), inability to engage in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing negative emotions (Goals), problems in controlling behavior impulsive when experiencing negative emotions (Impulses), limited access to emotion regulation strategies (Strategies) and lack of emotional clarity (Clarity) (exogenous variable), emotional regulation of adolescent children: dimensions lability/negativity and emotional regulation (endogenous variable) and coparenting: cooperation, conflict and triangulation dimensions (mediating variable). The description of the mean and standard deviation analyses is found in Table 1.

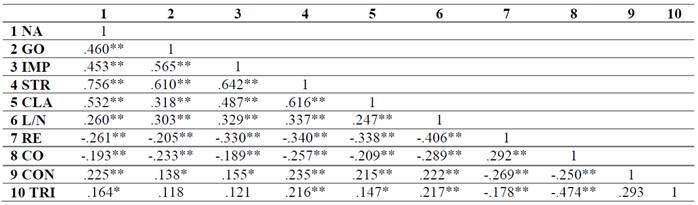

The experiences of emotional dysregulation of mothers measured by the DERS indicated that these are related to the mediation and outcome variables. After verifying that it was a non-normal sample, Spearman's correlation analysis was performed to assess the internal relationships between the dimensions. Many moderate and high correlations were observed, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Correlation between variables

Notes: 1 NA: nonacceptance; 2 GO: goals; 3 IMP: impulse; 4 STR: strategy; 5 CLA: clarity; 6 L/N: lability/negativity; 7 RE: emotion regulation; 8 CO: mother’s cooperation; 9 CON: mother’s conflict; 10 TRI: mother’s triangulation. ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2 extremity) * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2 extremity)

Structural Model

Structural equation modeling is a technique that allows separating relationships for each set of dependent variables, providing the appropriate and most efficient estimation technique for a series of separate multiple regression equations estimated simultaneously. In this sense, observing this model allows us to verify the paths of the independent variables (emotional dysregulation of mothers) with the dependent ones (emotional regulation of children) and the mediator (coparenting).

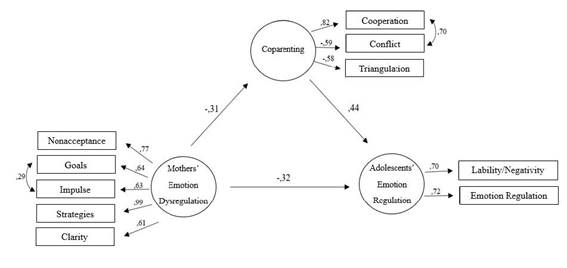

Initially, the model showed adequate data adjustment: CFI = .93, CMIN/DF = 2.40 and RMSEA = .08. However, adjusting the existing covariance between goals and impulses in the mothers' emotional dysregulation and in the cooperation and conflict of coparenting, the result showed an excellent adjustment of data: CFI = .97, CMIN/DF = 1.52 and RMSEA = .05.

As for the model's standardized regression coefficients, the directions already indicated that the dimensions of the mothers' emotional dysregulation negatively affect the perceived emotional regulation of adolescent children, as well as negatively in the mediating variable coparenting (showing a negative relationship with cooperation, and a positive relationship with conflict and triangulation). It has been identified that the prediction of the dimensions of emotional dysregulation of mothers for coparenting (β = 0.31) and for emotional regulation of adolescents (β = -0.32) showed moderate indices.

The standardized regression coefficients of the model indicate that the dimensions of emotional dysregulation presented high and moderate indices, with β = 0.99 for strategies, β = 0.77 for non-acceptance, β = 0.64 objectives, β = 0.63 impulses and β = 0.61 clarity. The coefficients of the coparenting latent variable showed high rates, with β = 0.82 for cooperation, β = -0.59 for conflict and β = -0.58 for triangulation. The coefficients of the dimensions of the emotional regulation variable of the adolescent children showed indices β = 0.70 for lability and β = 0.72 for emotional regulation, considered high indices.

In the case of the mediating variable, it is considered that the mothers' emotional dysregulation is reduced when we add the coparenting variable as an additional predictor (β = 0.44), therefore the mediation is sustained (partial). It is also identified that the magnitude of prediction of the cooperation dimension of the latent variable is high, which in turn has a strong impact on the emotional regulation of adolescent children. Figure 1 depicts the final model.

Discussion and Conclusions

The objective of this study was to verify the role of emotional dysregulation in mothers, as well as the possible mediation of coparenting in the emotional regulation of adolescent children from the perspective of mothers. Emotion regulation skills in adolescents are being linked with mental health protective factors (Antunes et al., 2018) if they are adaptive and with anxiety (Young et al., 2019), depression (Young et al., 2019) and suicidal ideation (Miller et al., 2018), in cases of emotional regulation deficits in adolescents. Given such magnitude, the results of this study demonstrate the importance of the family in the development of adolescent children, reinforcing what has been pointed out in research on coparenting and reverberation in children (Machado & Mosmann, 2019; Mosmann et al., 2018).

When evaluating the composition of the latent variables of the interaction model, corroborated with the averages and correlation indices, the data reflect a sample with levels of emotional dysregulation of mothers, indicating difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing negative emotions (β = 0.64), problems accepting negative emotions (β = 0.77) and limited access to emotion regulation strategies (β = 0.99), such as the dimensions with the highest means building the latent variable emotional dysregulation of mothers. These emotional dysregulation indices may be related to the mothers' overload of domestic and parental tasks. In 2017, a study by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) pointed out that mothers dedicate twice as much time as men to household chores and caring for people. In this sense, the overload of activities and the feeling of disproportionate responsibility for managing the household and the children are associated with the lack of emotional well-being of mothers (Ciciolla & Luthar, 2019).

However, a significant percentage of the sample reported diagnosis of mental disorders, such as anxiety disorders and mood disorders. These groups of disorders are associated with difficulties in emotion regulation. In the context of psychopathology, deficits in emotion regulation have negative relationships with the subject's well-being (Kraiss et al., 2020), so this is a sample of mothers with significant rates of mental disorder and consequently with difficulties in emotion regulation.

The composition of the coparenting variable was primarily composed of coparental cooperation (β = 0.82). Descriptive analyses show mothers with high levels of dysregulation, but who perceive themselves as having high levels of cooperation when referring to coparenting. This apparent contradiction could suggest that mothers who recognize their difficulties in emotional regulation may adopt a cooperative posture in their coparenting relationship, perhaps as a compensatory behavior. Aware of their individual difficulties, they seek support from the coparental pair.

In addition, it is known that caregivers tend to respond to studies about their parental performance more positively, giving socially desirable responses (Almiro, 2017). This bias is still one of the biggest challenges in evaluating psychological phenomena. It is possible that the high levels of cooperation are expressing a positive self-evaluation of these mothers in their coparenting posture.

These particularities contributed to the formation of specific aspects of this sample. However, in addition to the characteristics of this group, the relationships between the constructs emotional dysregulation of mothers and emotional regulation of children and coparenting were investigated, both in terms of relationships and correlations, as well as in terms of interactions in the proposed model, supporting the scientific literature in the field and advancing the understanding in some areas.

Based on these considerations, this study yielded two main results. The first result is related to the mediating role of coparenting between the emotional dysregulation of mothers and the emotional regulation of adolescent children. In the case of children's emotional regulation, the Interactional Model pointed out that three observable variables were highly influential and proved to be strongly explanatory for this construct: the dimension lack of strategies and non-acceptance of the mother's emotions (in the latent variable emotional dysregulation of mothers) and coparenting cooperation (in the latent variable coparenting). These observable variables were significant in explaining the model, highlighting that the dimensions of coparenting cooperation (.82) (positively impacting) and lack of strategies to regulate the mother's emotions (.99) (negatively impacting) were substantially greater than the other variables.

In this sense, by inserting the latent variable coparenting in the structural equation, the strength of the impact of the emotional dysregulation variable of mothers on the emotional regulation of their children was reduced (Hair et al., 2010), showing partial mediation of coparenting between them. This means that, in addition to what has already been foreseen about learning emotional regulation through social learning and modeling (Morris et al. 2007; Reindl et al., 2018), observed in the direct relationship the coparenting subsystem, the way in which the parental couple performs their functions in the family (Costa et al., 2017; Margolin et al., 2001) is part of this relationship.

These findings show the potential of cooperation in coparenting, indicating that the positive relationship between caregivers can reverberate in the quality of the children's mental health. Most research on coparenting has focused on its negative dimensions, as it has been noted in previous studies (Margolin et al., 2001). However, theorists who study this topic point out that the quality of coparenting in the family seems to be more important for the child's functioning than other aspects of the couple (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2001). This finding provides more substantial evidence in support of existing research indicating that coparental cooperation is related to the socio-emotional adjustment of children (Choi et al., 2019), as it is the dimension that most positively impacts the emotional regulation of adolescent children.

It should also be noted that the emotional dysregulation of mothers had an indirect effect on the emotional regulation of adolescent children. This result can be better explained by the fact that the emotional dysregulation of the mothers affects the emotional regulation of the children if it is directed towards the adolescent and not acting only on an individual level. This finding is consistent with some studies that examined the emotional dysregulation of mothers, suggesting that this variable was related to consequences in the offspring (Giordano et al., 2021), which were not limited to direct effects on the emotional regulation of the children.

In this sense, the second main result of this study is related to the emotional dysregulation of mothers having a negative effect on coparental cooperation and a positive effect on conflict and coparental triangulation. Although the mothers in this sample declared themselves cooperative, the negative path of the latent variable mothers' emotional dysregulation to coparenting indicates that the mothers' emotional dysregulation reported in the DERS could predict a lower ability to cooperate with the coparenting partner. This result may be related to the fact that mothers need to have emotional regulation skills to cooperate with their coparental partner. This was also observed in the correlations in which the negative direction corresponds to mothers who were more dysregulated having lower levels of coparental cooperation. Consequently, this low cooperation can impact on lower emotional regulation of children.

This data contributes to the existing research on coparenting by building on previous findings regarding personal variables that influence the quality of the coparenting relationship. Factors such as marital quality before the birth of the child (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007), stress (Kang et al., 2022), and the ability to solve problems (Majdandžić et al., 2012) are necessarily permeated by emotional regulation (McRae & Gross, 2020) of parents in a coparenting relationship.

Overall, the present study suggests that the quality of coparenting, specifically coparenting cooperation, is associated with the emotional regulation of adolescent children, and that the emotional dysregulation of mothers seems to have a detrimental impact on coparenting cooperation. Given the importance of coparenting for children and the well-being of the family (Costa et al., 2017; Mosmann et al., 2018), these results indicate, in the clinical context, that taking a preventative approach with parents, through interventions that provide emotional regulation support for the development of skills in the exercise of the coparenting subsystem, are essential for the adaptive development of children (Frizzo et al., 2005).

Some limitations of this study need to be discussed. First, this study was applied during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, while fathers, mothers, other caregivers and children were confined, which consequently increases stress levels (Freisthler et al., 2021). The pandemic situation may have had an impact on the results of emotional dysregulation reported by mothers. Another important limitation is related to the cross-sectional design method. Longitudinal research could test temporal relationships between constructs and the chronological order of variables. Another important consideration is that the research adopts only the perspective of mothers. It is possible that if we added the perspectives of parents and adolescents about coparenting and emotional regulation, the results could be different. Finally, regarding future directions of research on emotional regulation of parents and adolescents and the role of coparenting, there could be an investigation about which emotional regulation strategies are related to the dimensions of coparenting, in addition to investigating the variables from the perceptions of the father, the mother and the child, which may provide answers about the dynamics of dyadic and triadic interactions that occur in coparenting.

REFERENCES

Almiro, P. A. (2017). Uma nota sobre a desejabilidade social e o enviesamento de respostas. Revista Avaliação Psicológica, 16(03). https://doi.org/10.15689/ap.2017.1603.ed [ Links ]

Antunes, J., Matos, A. P., & Costa, J. J. (2018). Regulação emocional e qualidade do relacionamento com os pais como preditoras de sintomatologia depressiva em adolescentes. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental, Especial, 6, 52-58. https://doi.org/10.19131/rpesm.0213 [ Links ]

Bariola, E., Gullone, E., & Hughes, E. K. (2011). Child and adolescent emotion regulation: the role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(2), 198-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5 [ Links ]

Barnett, M. A., Scaramella, L. V., McGoron, L., & Callahan, K. (2011). Coparenting cooperation and child adjustment in low-income mother-grandmother and mother-father families. Family Science, 2(3), 159-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2011.642479 [ Links ]

Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., Lundh, L. G., Bjärehed, J., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., Hellner Gumpert, I., & Gratz, K. L. (2016). Development and validation of a Brief Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 284-296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x [ Links ]

Blair, B. L., Gangle, M. R., Perry, N. B., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & Shanahan, L. (2016). Indirect effects of emotion regulation on peer acceptance and rejection: the roles of positive and negative social behaviors. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 62(4), 415-439. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.62.4.0415 [ Links ]

Campbell, C. G. (2022). Two decades of coparenting research: a scoping review. Marriage & Family Review, 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2022.2152520 [ Links ]

Cheung, R. Y. M., Chan, L. Y., & Chung, K. K. H. (2020). Emotion dysregulation between mothers, fathers, and adolescents: Implications for adolescents’ internalizing problems. Journal of Adolescence, 83(January), 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.07.001 [ Links ]

Choi, J. K., Parra, G., & Jiang, Q. (2019). The longitudinal and bidirectional relationships between cooperative coparenting and child behavioral problems in low-income, unmarried families. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(2), 203-214. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000498 [ Links ]

Ciciolla, L. & Luthar, S. S. (2019). Invisible household labor and ramifications for adjustment: mothers as captains of households. Sex Roles, 81(7-8), 467-486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-1001-x [ Links ]

Costa, C., Machado, M., Schneider, M., Mosmann, C. (2017). Subsistema coparental: revisão sistemática de estudos empíricos. Psico, 48(4), 339-351. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2017.4.25386 [ Links ]

Crandall, A. A., Ghazarian, S. R., Day, R. D., & Riley, A. W. (2016). Maternal emotion regulation and adolescent behaviors: The mediating role of family functioning and parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(11), 2321-2335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0400-3 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2010). Projeto de pesquisa: métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto (2nd ed.). Bookman. [ Links ]

Cui, L., Criss, M. M., Ratliff, E., Wu, Z., Houltberg, B. J., Silk, J. S., & Morris, A. S. (2020). Longitudinal links between maternal and peer emotion socialization and adolescent girls’ socioemotional adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 595-607. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000861 [ Links ]

D’Agostino, A., Covanti, S., Rossi Monti, M., & Starcevic, V. (2017). Reconsidering emotion dysregulation. Psychiatric Quarterly, 88(4), 807-825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9499-6 [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009). Uma introdução à pesquisa qualitativa (3rd ed.). Artmed/Bookman. [ Links ]

Freisthler, B., Gruenewald, P. J., Tebben, E., McCarthy, K. S., & Price Wolf, J. (2021). Understanding at-the-moment stress for parents during COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions. Social Science & Medicine, 279, 114025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114025 [ Links ]

Frizzo, G. B., Kreutz, C. M., Schmidt, C., Piccinini, C. A., & Bosa, C. (2005). O conceito de coparentalidade e suas implicações para a pesquisa e para a clínica: implication for research and clinical practice. Journal of Human Growth and Development, 15(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.19774 [ Links ]

Gallegos, M. I., Murphy, S. E., Benner, A. D., Jacobvitz, D. B., & Hazen, N. L. (2017). Marital, parental, and whole-family predictors of toddlers’ emotion regulation: The role of parental emotional withdrawal. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(3), 294-303. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000245 [ Links ]

Gil, A. (2010). Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa (5th ed.). Atlas. [ Links ]

Giordano, C., Lo Coco, G., Salerno, L., & Di Blasi, M. (2021). The role of emotion dysregulation in adolescents’ problematic smartphone use: A study on adolescent/parents triads. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 106632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106632 [ Links ]

Gratz, K. L. & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41-54. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94 [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [ Links ]

Inwood, E. & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: a systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(2), 215-235. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12127 [ Links ]

Kang, S. K., Choi, H. J., & Chung, M. R. (2022). Coparenting and parenting stress of middle-class mothers during the first year: bidirectional and unidirectional effects. Journal of Family Studies, 28(2), 551-568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2020.1744472 [ Links ]

Karaer, Y. & Akdemir, D. (2019). Parenting styles, perceived social support and emotion regulation in adolescents with internet addiction. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 92, 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.03.003 [ Links ]

Koch, C., Schaefer, J. R., Schneider, M., & Mosmann, C. (2020). Coparentalidade e conflito pais-filhos em adolescentes envolvidos em práticas restaurativas. Psico-USF, 25(2), 343-355. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712020250212 [ Links ]

Kraiss, J. T., ten Klooster, P. M., Moskowitz, J. T., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The relationship between emotion regulation and well-being in patients with mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102, 152189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152189 [ Links ]

Kwon, K., Hanrahan, A. R., & Kupzyk, K. A. (2017). Emotional expressivity and emotion regulation: Relation to academic functioning among elementary school children. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 75-88. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000166 [ Links ]

Lewis, J., Binion, G., Rogers, M., & Zalewski, M. (2020). The associations of maternal emotion dysregulation and early child dissociative behaviors. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 21(2), 203-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1678211 [ Links ]

Li, D., Li, D., Wu, N., & Wang, Z. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of emotion regulation through parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: tests of unique, actor, partner, and mediating effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 101(December 2018), 113-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.038 [ Links ]

Machado, M. R. & Mosmann, C. P. (2019). Dimensões negativas da coparentalidade e sintomas internalizantes: a regulação emocional como mediadora. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 35(Spec. Iss.), e35nspe12. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e35nspe12 [ Links ]

Macie, K. M. & Stolberg, A. L. (2003). Assessing Parenting After Divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 39(1-2), 89-107. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v39n01_06 [ Links ]

Majdandžić, M., de Vente, W., Feinberg, M. E., Aktar, E., & Bögels, S. M. (2012). Bidirectional associations between coparenting relations and family member anxiety: a review and conceptual model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(1), 28-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0103-6 [ Links ]

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: a link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3 [ Links ]

McRae, K. & Gross, J. J. (2020). Emotion regulation. Emotion, 20(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000703 [ Links ]

Miguel, F. K., Giromini, L., Colombarolli, M. S., Zuanazzi, A. C., & Zennaro, A. (2017). A Brazilian investigation of the 36- and 16-item Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scales. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(9), 1146-1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22404 [ Links ]

Miller, A. B., McLaughlin, K. A., Busso, D. S., Brueck, S., Peverill, M., & Sheridan, M. A. (2018). Neural correlates of emotion regulation and adolescent suicidal ideation. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.08.008 [ Links ]

Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Silk, J. S., & Houltberg, B. J. (2017). The Impact of Parenting on Emotion Regulation During Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 233-238. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12238 [ Links ]

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361-388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x [ Links ]

Mosmann, C. & Wagner, A. (2008). Dimensiones de la conyugalidad y de la parentalidad: un modelo correlacional. Revista Intercontinental de Psicología y Educación, 10(2), 79-103. [ Links ]

Mosmann, C. P., Costa, C. B., Einsfeld, P., Silva, A. G. M., & Koch, C. (2017). Conjugalidade, parentalidade e coparentalidade: associações com sintomas externalizantes e internalizantes em crianças e adolescentes. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas ), 34, 487-498. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752017000400005 [ Links ]

Mosmann, C., Costa, C., Silva, A. & Luz, S. K. (2018). Filhos com sintomas psicológicos clínicos: papel discriminante da conjugalidade, coparentalidade e parentalidade. Temas em Psicologia, 26(51), 429-442. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.1-17Pt [ Links ]

Pallini, S., Vecchio, G. M., Baiocco, R., Schneider, B. H., & Laghi, F. (2019). Student-teacher relationships and attention problems in school-aged children: the mediating role of emotion regulation. School Mental Health, 11(2), 309-320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9286-z [ Links ]

Perry, N. B., Dollar, J. M., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & Shanahan, L. (2020). Maternal socialization of child emotion and adolescent adjustment: Indirect effects through emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 541-552. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000815 [ Links ]

Qian, Y., Chen, F., & Yuan, C. (2020). The effect of co-parenting on children’s emotion regulation under fathers’ perception: a moderated mediation model of family functioning and marital satisfaction. Children and Youth Services Review, 119(October), 105501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105501 [ Links ]

Reindl, V., Gerloff, C., Scharke, W., & Konrad, K. (2018). Brain-to-brain synchrony in parent-child dyads and the relationship with emotion regulation revealed by fNIRS-based hyperscanning. NeuroImage, 178(May), 493-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.060 [ Links ]

Reis, A. H., Silva De Oliveira, S. E., Bandeira, D. R., Andrade, N. C., Abreu, N., & Sperb, T. M. (2016). Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC): estudos preliminares da adaptação e validação para a cultura Brasileira. Temas Em Psicologia, 24(1), 77-96. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.1-06 [ Links ]

Riina, E. M., Lee, J.-K., & Feinberg, M. E. (2020). Bidirectional associations between youth adjustment and mothers’ and Fathers’ coparenting conflict. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(8), 1617-1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01262-6 [ Links ]

Sabadini, A; Sampaio, M., & Koller, S. (2009). Publicar em Psicologia: um enfoque para a revista científica. Associação Brasileira de Editores Científicos de Psicologia. [ Links ]

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Frosch, C. A. (2001). Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers’ externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(3), 526-545. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.3.526 [ Links ]

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Brown, G. L., & Szewczyk Sokolowski, M. (2007). Goodness-of-fit in family context: Infant temperament, marital quality, and early coparenting behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 30(1), 82-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.008 [ Links ]

Shields, A. M. & Cicchetti, D. (1995). The development of an emotion regulation assessment battery: Reliability and validity among at-risk grade-school children (Apresentação da conferência). Society for Research on Child Development, Indianapolis, Estados Unidos. [ Links ]

Szkody, E., Steele, E. H., & McKinney, C. (2020). Links between parental socialization of coping on affect: Mediation by emotion regulation and social exclusion. Journal of Adolescence, 80(June 2019), 60-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.02.004 [ Links ]

Teubert, D. & Pinquart, M. (2011). The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA) reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 206-215. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000068 [ Links ]

Thomassin, K., Suveg, C., Davis, M., Lavner, J. A., & Beach, S. R. H. (2017). Coparental affect, children’s emotion dysregulation, and parent and child depressive symptoms. Family Process, 56(1), 126-140. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12184 [ Links ]

Williams, W. C., Morelli, S. A., Ong, D. C., & Zaki, J. (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115, 224-254. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000132 [ Links ]

Young, K. S., Sandman, C. F., & Craske, M. G. (2019). Positive and negative emotion regulation in adolescence: links to anxiety and depression. Brain Sciences, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9040076 [ Links ]

How to cite: Dalla Corte Euzebio, L. & Pereira Mosmann, C. (2023). Coparenting as a mediator between mothers’ emotion dysregulation and the perception of adolescents’ emotion regulation. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2583. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2583

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. L. D. C. E. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; C. P. M. in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: May 26, 2021; Accepted: May 04, 2023

texto em

texto em

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI