Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Ciencias Psicológicas

Print version ISSN 1688-4094On-line version ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.1 Montevideo 2023 Epub June 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2872

Original Articles

Psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Bullied Questionnaire for Children in Spanish

1 Universidad Argentina de la Empresa, Conicet, Argentina, resettsantiago@gmail.com

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Conicet, Argentina

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Conicet, Argentina

Bullying is an important risk factor for the mental health of children and adolescents, since victims’ present higher levels of emotional problems while those who carry it out show greater behavioural problems. Despite its relevance, few instruments exist for its measurement in school-age children. The present study sought to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in a Spanish-speaking sample, with the particularity of being the first analysis of Spanish-speaking children. A quantitative study was carried out, implementing AFE, AFC, and Spearman's correlations. An intentional sample of 670 Argentinian children, male (48 %) and female (52 %), from 10 to 12 years old (mean age= 10.80; SD = 0.72) answered this test, such as the Friendship Quality Scale and the Kovacs Depression Inventory. The results indicated a factorial structure of two dimensions called victimization and bullying that coincided with those postulated by the author of the questionnaire. Cronbach's and Omega's alphas were satisfactory. The evidence of concurrent validity with the perception of the quality of friendship and depression was confirmed. The results indicated that this questionnaire presented adequate psychometric properties in its adaptation to Argentinian Spanish.

Keywords: bullying; children; psychometric properties; bully; bullied.

El bullying es un importante factor de riesgo para la salud mental de niños y adolescentes, ya que las víctimas presentan mayores niveles de problemas emocionales; mientras que los acosadores muestran mayores problemas de conducta. A pesar de su relevancia, existen pocos instrumentos para su medición en niños de edad escolar. El presente estudio buscó evaluar las propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus en una muestra de habla hispana, con la particularidad de ser el primer análisis de habla hispana en niños. Se realizó un estudio instrumental, implementando AFE, AFC y correlaciones de Pearson. Una muestra intencional de 670 niños argentinos, varones (48 %) y mujeres (52 %), de 10 a 12 años (edad media = 10.80; DE = .72) contestaron el cuestionario, la Escala de Calidad de la Amistad y el Inventario de Depresión de Kovacs. Los resultados indicaron una estructura factorial de dos dimensiones: victimización y bullying, que coincidieron con las postuladas por el autor del cuestionario. Los valores de los coeficientes alfas de Cronbach y de omega de McDonald fueron satisfactorios. Se confirmó la evidencia de validez concurrente con la percepción de la calidad de la amistad y la depresión. El cuestionario presentó adecuadas propiedades psicométricas en su adaptación al español argentino.

Palabras clave: acoso escolar; niños; propiedades psicométricas; bullying; victimización.

O bullying é um importante fator de risco para a saúde mental de crianças e adolescentes, uma vez que as vítimas apresentam maiores níveis de problemas emocionais enquanto aqueles que o praticam apresentam maiores problemas comportamentais. Apesar de sua relevância, existem poucos instrumentos para sua mensuração em crianças em idade escolar. O presente estudo procurou avaliar as propriedades psicométricas do Questionário Revisado de Bullying/ Vitimização de Olweus em uma amostra de língua espanhol, com a particularidade de ser a primeira análise em língua espanhola em crianças. Foi realizado um estudo instrumental, implementando AFE, AFC e correlações de Pearson. Uma amostra intencional de 670 crianças argentinas, meninos (48 %) e meninas (52 %), com idades de 10 a 12 anos (média de idade = 10,80; DP = 0,72) responderam ao questionário, a Escala de Qualidade da Amizade e o Inventário de Depressão de Kovacs. Os resultados indicaram uma estrutura fatorial de duas dimensões denominadas vitimização e bullying, que coincidiram com as postuladas pelo autor do questionário. Os valores dos coeficientes alfas de Cronbach e Omega de McDonald foram satisfatórios. Foi confirmada a evidência de validade concorrente com a qualidade percebida da amizade e a depressão. O questionário apresentou propriedades psicométricas adequadas em sua adaptação ao espanhol argentino.

Palavras-chave: assédio escolar; crianças; propriedades psicométricas; bullying; vitimização.

Bullying by peers is considered an important risk factor for the mental health of children and adolescents (Barbarro et al., 2020; Card & Hodges, 2008; Card et al., 2007; Nansel et al., 2004; Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

Bullying can be carried out in different ways: verbal (calling names, teasing, insults, etc.), physical (hitting, kicking, shoving, etc.), and indirectly, that is, without using direct physical or verbal contact with the victim (Resett, 2021; Rigby et al., 2004): spread rumours or exclude.

Both being a victim of bullying and carrying it out are risk factors for developmental psychopathology (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Nansel et al., 2004). Victims generally present higher levels of emotional problems, such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem (Olweus, 2013; Roth et al., 2015) and suicidal ideation (Quintero-Jurado et al., 2021), while those who commit it present a pattern of behaviour problems, such as antisocial behaviour, consumption of toxic substances, among others (Farrington & Ttofi, 2011; Nansel et al., 2004). It could be said that the victims would be prone to internalizing problems, while the aggressors would be prone to externalizing problems (Olweus, 1993, 2013). According to the model of externalizing and internalizing problems, the former affect the internal world of the person, with a maladaptive way of resolving conflicts, this resolution being internal level such as anguish, depression, suicidal ideation, etc. For their part, the latter would affect the external world of the person, with expression of emotional conflicts outwards, with impulsive discharge and externalization of aggression (Achenbach, 2008; Arnett, 2020; Caballero et al., 2018; Luk et al., 2016; Steinberg, 2018) A meta-analysis of 18 studies with schoolchildren detected an association between victimization with emotional, behavioural, and interpersonal problems. On the other hand, an association has been reported between bullying and externalizing problems, interpersonal problems, and poor school performance (Klajakovic & Hunt, 2016).

In general, the victims and perpetrators of bullying have a higher risk of presenting a worse psychosocial adjustment. Previous studies show that levels of friendship quality in children and adolescents are negatively related to being a victim or perpetrator of bullying (Rodriguez et al., 2015; Rodriguez et al, 2021). Since both the victims and those who carry out the bullying present this greater risk, it is vital to develop, use and adapt instruments with solid psychometric benefits to identify them. There are numerous techniques to measure this problem: structured observations, interviews, teacher and student nominations, self-reports, among others (Hartung et al., 2011). Self-reports, like questionnaires, have the advantage that they are techniques that are easy to apply and interpret, with low economic costs, and that can be applied on multiple occasions to see how the phenomenon evolves. Although there are numerous bullying measurement scales, not all of them have an exact definition of it or present its particularities such as power imbalance, repetition, among others (Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2014). The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, (Olweus, 1996) for children and adolescents is one of the instruments used in the world to measure this problem (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010). According to Olweus (1993), the advantages of this questionnaire are: to provide students with a clear definition of what is meant by bullying, to ask about bullying that has occurred in the last few months, and to present a time frequency of responses. The two main dimensions measured by the questionnaire are: bullying and being victimized (Olweus, 1994). This questionnaire has been used in numerous studies in different countries and its psychometric virtues were solidly proven, both with respect to its internal consistency, with very acceptable Cronbach's alphas fluctuating between .80 and .90 in numerous foreign studies both for the victimization dimension as for bullying (Olweus, 2013), as well as in relation to its validity and the property of differentiating between the students involved in the aggression and in being victimized (Solberg & Olweus, 2003). It has been adapted and translated in many countries and languages, such as the Netherlands, Japan, the United States, among others (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010; Gaete et al., 2021; Kyriakides et al., 2006; Lee & Cornell, 2009; Resett, 2018). The studies of the author of the test indicated that it presents adequate reliability and concurrent validity (Olweus, 2013). Regarding its concurrent validity, a linear association of victimization with emotional problems (depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem) and bullying with behavioural problems (antisocial behaviour, aggressiveness, and consumption of toxic substances) was demonstrated (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018).

Although bullying becomes more prevalent in the adolescent years, it is crucially important to identify potential victims and aggressors early, since in adolescence interventions to prevent and reduce bullying are less effective than in childhood (Resett & Mesurado, 2021). Furthermore, although empirical studies are scarcer in childhood than in adolescence, they show similar levels of prevalence of being victimized and bullying in both stages of the life cycle. Globally, it is noted that one in three children suffered from bullying in the last 30 days (Armitage, 2021). A study with children and adolescents in 16 Latin American countries found that Argentina was the country with the highest levels of physical bullying (Román & Murillo, 2011). In Argentina, specifically, 13% of victims, 10% of harassers and 5% of both were found in child samples (Resett, 2021). Research in Spain found 9% victims, 1% bullies, and 1% of both groups in children's shows (Babarro et al., 2020). Although the psychometric properties of said questionnaire were examined in samples of Argentinian adolescents, indicating adequate factorial structure, internal consistency, and concurrent validity (Resett, 2011, 2018), there are no studies in that country, as in Spanish-speaking nations, that have examined its properties in samples of school-age children.

In Argentina, as in many other countries in the region, most of the studies that have been carried out on bullying are of a theoretical nature and there is little scientific-empirical data in this regard and, even less, using instruments of recognized properties. Despite this fact, in recent years, research has been conducted on adolescents (Gaete et al., 2021; Resett, 2011, 2018) and children (Gaete et al., 2021; Resett, 2021).

Thus, it is vitally important to examine in a Latin American country and a cultural tradition different from that of the Nordic nations and North America if the instrument developed by Olweus retains its good psychometric properties. Thus, the strength of this study is that it is the first to evaluate the psychometric properties in a sample of Spanish-speaking children. As the Olweus questionnaire is an instrument widely used worldwide, its adaptation would allow a comparison of the levels of bullying reported internationally and a prompt identification of the problem.

Aims

To explore evidence of the factorial structure of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in children and the internal consistency of this questionnaire.

To examine evidence of concurrent validity regarding depressive symptomatology and friendship quality.

Method

Participants

670 children selected in a non-probabilistic way participated in this research, males (48 %) and females (52 %), from 10 to 12 years old, with a mean age of 10.80 years (SD = 0.72) of average socioeconomic level. They belonged to 7 private (5 schools) and public (2 schools) primary level schools in the city of Paraná, province of Entre Ríos, Argentina, who were in the fifth and sixth grade of said educational levels. The inclusion criteria were to be between 10 and 12 years old, reside in Paraná, attend private or public primary school, and attend fifth or sixth grade.

Instruments

Bullying and victimization. RevisedOlweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1996). It consists of 38 questions to measure problems related to bullying in children and adolescents. In the first place, this instrument gives students a definition of what is to be understood by bullying, since bullying is a complex phenomenon and can be confused by students with other types of conflict between peers (Phillips & Cornell, 2012). Then comes the global question about whether they were victimized -in another section of the questionnaire they inquire about whether other students were bullied-: “Since classes started, how many times have you been harassed at school?” To make the measurement more precise and sensitive to change, the questionnaire asks about these behaviours in recent months. Next, the students are questioned about the different types of bullying they experienced -or that they carried out in the other part of the questionnaire-, based on nine questions about the frequency of the different forms of bullying: hitting, taking or breaking things, name calling, body teasing, sexual teasing, threats, excluding, lying, SMS or Internet bullying or other forms of being harassed or harassed; that is, physical (two questions), verbal (four), indirect or relational (two) and cyberbullying (one). The nine questions about being victimized and bullying can be added or averaged to make a scale, since they constitute the two large dimensions evaluated by this questionnaire (Kyriakides et al., 2006; Olweus, 1994, 2013). Examples of items are: “I was called ugly names, hit hard, or made fun of” (being victimized).

The Olweus Questionnaire uses the following response alternatives: Never, Once or twice, Two or three times a month, More or less once a week, and Several times a week. Responses are generally coded as 0 (Never) to 4 (Several times a week). In the present study, the Spanish version used by previous studies in Argentinian adolescents was used, which demonstrated good properties, such as construct validity, internal reliability, and concurrent validity (Resett, 2011, 2018). The author of the test points out that the version used in adolescents can be applied to children older than 10 years (Olweus, 1996). The version in Argentinian Spanish and the original are similar with the only difference that the first in the item verbal bullying by race or ethnicity was changed to "skin colour", since in its translation and adaptation process independent judges suggested said change for its ecological validity (Resett, 2018). The novelty of the present study is that the psychometric properties are evaluated in a sample of children, since the remaining studies in that country were in samples of adolescents. In this paper, only the questions of the victimization and bullying scales will be reported, since the remaining items are not part of these scales.

Friendship Quality Scale for children (Resett et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2015), Spanish version of the Friendship qualities Scale version 4.1 from Bukowski et al. (1994). The children must mention the name of their best friend, the gender and if they attend the same course and then answer 33 items that describe qualities of friendship, indicating the degree of agreement with them. This questionnaire comprises six subscales or dimensions of friendship. They are: Fellowship: amount of volunteer time that friends share or spend together; Balance: balance in reciprocity, if in the friendship bond one of the subjects offers more than the other; Conflict: fights or arguments within the friendship relationship, disagreements in it; Help: mutual help and assistance, as well as help in conflict situations that can be experienced with other colleagues; Security: belief that when you need it, the friend is reliable and you can trust him or her (reliable alliance); y Proximity: feelings of affection or feeling special within the bond of friendship with each other, as well as the union of the bond. The questionnaire presents 4 alternatives responses: 1 (Totally disagree) to 4 (Totally agree). Regarding preliminary psychometric studies in Argentina, the Friendship Quality Scale has shown acceptable internal reliability indices for each of its subscales, with the following Cronbach's alpha coefficients: Companionship (.61), Help (.80), Safety (.70), Proximity (.81), Conflict (.80) and Balance (.65). The final version includes 7 items from the proximity dimension, 6 conflict items, 3 balance items, 5 companionship items, 7 help items, and 5 security items, that is, a total of 33 items. It presents good psychometric properties in Spanish, such as internal consistency (Rodriguez, 2015) and concurrent validity with family relationships (Rodriguez et al., 2021). In the present study, Cronbach's alphas were adequate with .82 for Closeness, .68 for Conflict, .61 for Balance, .81 for Help, .65 for Companionship, and .58 for Safety.

Kovacs Depression Inventory for Children (Kovacs, 1992). This questionnaire, one of the most widely used in the world, measures depressive syndrome in children and adolescents from 7 to 17 years of age. It consists of 27 items of three alternatives each. Higher scores imply greater depression. Its psychometric virtues are well established in Argentine samples, as adequate internal consistency, with values around .84 and concurrent validity with interpersonal relationships and behaviour problems (Facio et al., 2006). Cronbach's alpha of said inventory was .83 in the present sample.

Data collection

In the first place, principals of the schools were contacted in order to request authorization. Once the authorization of the directors was obtained, a note was sent in the student's communication notebook in order to request parental authorization. Anonymity, confidentiality and voluntary participation were ensured.

Data collection was carried out during class hours, within the classrooms and at the group level, with self-reports presented in paper format. During the sessions, two researchers from the project were always present to help the children in the event that there was any difficulty in understanding the instructions. The project was approved by a committee at the university that funded the research.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed in the SPSS version 23 Statistical Package for the Social Sciences program to obtain descriptive statistics (percentages, means, deviations, etc.) and inferential statistics (Cronbach's alphas, Spearman correlations, etc.). Parametric analyzes were performed because the bullying scale values had a relatively normal distribution: asymmetry ranged from 1.71 to 4.75 and kurtosis ranged from 2.08 to 7.18, since values greater than 3 for the former and greater than 8 for the latter are considered extreme (Boomsma & Hoogland, 2001), while other authors postulate values of 10 or more as extreme (Kline, 2015; Weston & Gore, 2006). Although the response format is ordinal, as in many other psychological tests, its distribution warrants that the data be treated continuously as indicated by other investigations (Schmidt et al., 2008) and as was done in adolescent samples with said instrument (Resett, 2011, 2018). For the remaining variables the values were .08 and 2.45 and .05 and 6.00, respectively.

First, the sample was randomly divided into two groups of 300 and 370, respectively. An exploratory factorial analysis (calibration study) was carried out with the first group using the maximum likelihood method, asking for eigenvalues greater than 1 and with Oblimin rotation -for related factors-, because principal component analysis is currently not recommended (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). To determine factor retention, the classical implementation method of Horn (1965) was used. For retention, empirical eigenvalues were compared with random eigenvalues (means), then those above the random mean were selected (O'Connor, 2000). A number of replications equal to 100 and percentile representation of simulations equal to .95 were used.

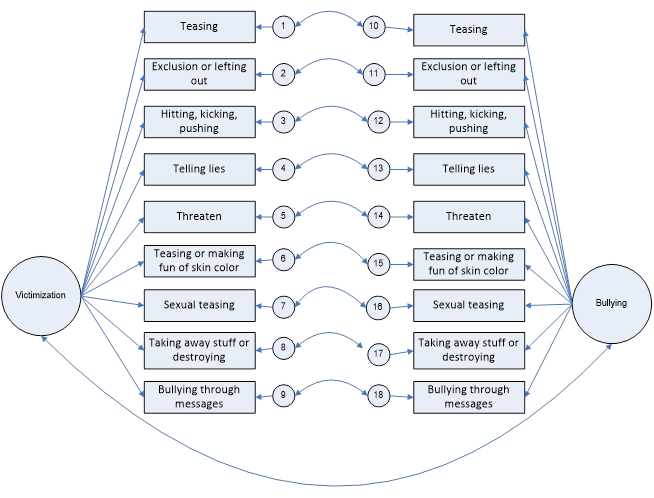

With the second sample, a confirmatory factor analysis (replication study) was carried out with the MPLUS version 6 program to test the two-factor model postulated by the author of the test (Olweus, 2013; Solberg & Olweus, 2003) and also verified in studies of the questionnaire in adolescents (Resett, 2018), as shown in Figure 1. This approach was chosen based on the data -first an exploratory analysis and then a confirmatory one- because it is known that the factorial structures of an instrument may vary from one study to another or when a test is being adapted (Fehm & Hoyer, 2004; Wells & Davies, 1994). If a different model emerged from the factor analysis, this would also be tested to compare its fit. One of two independent or unrelated factors was also tested. Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (WLSMV) because the responses to the items were ordinal with five response options, as suggested (Brown, 2006, Li, 2016; Lloret -Segura et al., 2014).

To consider whether the model was acceptable, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the average of the squared standardized residuals (RMSEA) were taken into account, since (2 statistic is very sensitive to sample size (Byrne, 2010, 2012). CFI and TLI values above .90 and RMSEA below .10 are considered adequate (Bentler, 1992; Byrne, 2010). There are also more demanding criteria with more than .95 and less than .05, respectively (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

For the analysis of internal consistency, in addition to Cronbach's alpha, the Omega was used due to the categorical nature of the alternatives that was extracted with the Jamovi 2.2.5 program.

Results

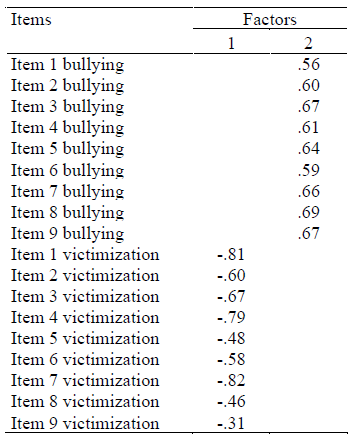

In order to evaluate the factor structure of the Olweus Questionnaire in children, an exploratory factor analysis was first carried out with the victimization and bullying items. The KMO index = .88, (2 (153) = 4046.04 p < .001 indicated that it was adequate to carry it out. Table 1 presents the results of the analysis. As shown in this table, two factors emerged: one is called victimization and the other bullying. When comparing the empirical eigenvalues with the random eigenvalues (means), the analysis indicated that it was appropriate to retain two that scored above the random eigenvalues, since the first two empirical values were 5.83 2.04 and the random ones scored 1.29 and 1.23, with the remaining values of the empirical analysis being below. All items loaded in their respective dimension with no cross-loads greater than .30.

Table 1: Factor Loadings for Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Revised Olweus Questionnaire in Children

Note: Only loads greater than .30 are presented.

As shown in Table 1, these two factors emerged, explaining a variance of 23 % and 19 %, respectively.

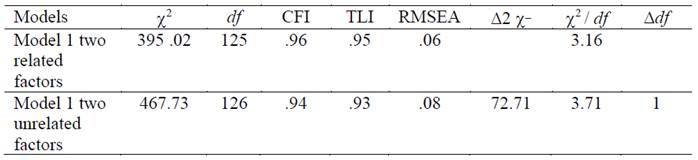

Confirmatory factor analysis was then carried out. A two-unrelated-factor model was also tested.

Regarding the confirmatory factor analysis, Table 2 shows the results of the analysis. As shown in that table, the two-associated-factor model yielded a better fit than the two-unrelated-factor model, as indicated by higher CFI, lower TLI, and RMSEA values, respectively.

Table 2: Fit Indices of the Revised Olweus Questionnaire Models in Children

Notes:df: degrees of freedom; CFI: Comparative Fixed Index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA: root mean square residual; (2/df value of (2 divided by the degrees of freedom; ∆(2 difference of (2 between the models; ∆df difference between the degrees of freedom of the models.

The factor loadings of the two related factors model were all significant and ranged from .41-.94. The correlation between both dimensions was .43, p < .001

When calculating Cronbach's alpha, it was .74 for the scale of being victimized and .81 for the bullying scale. The Omega coefficient was .75 and .83, respectively.

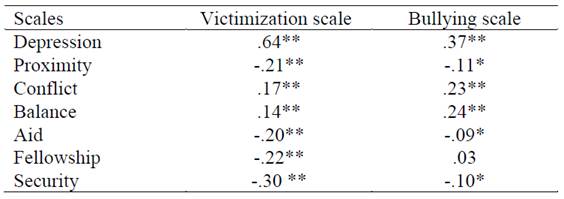

To observe the concurrent validity of the victimization and bullying scale, Spearman correlations were carried out between them and the Kovacs depression scale and the friendship scales of Bukowski et al. Table 3 shows the results of this analysis.

Table 3: Correlations between Olweus Victimization and Bullying Scales and Depression Scale and Friendship Scales

* p < .05 ** p < .01

As shown in Table 3, both the victimization and bullying scales correlated significantly with depression scores; the victimization scale was negatively correlated with proximity, help, companionship, and safety, and positively correlated with conflict and balance. The bullying scale was positively associated with conflict and balance scores, while it was negatively associated with proximity, helpfulness, and safety.

Discussion

The importance of this research lay in evaluating for the first time the factorial structure of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in a sample of children from Argentina to measure a highly topical phenomenon of notable psychological relevance, such as bullying. The psychometric properties of this test were evaluated in adolescents from that country, but not in children, for this reason the research was of great relevance.

Regarding the exploratory factorial analysis, the results yielded a model of two related factors that could be called victimization and bullying, without cross-loading and loading all in their respective factor. These two dimensions are those postulated by the author of the test (Olweus, 1996, 2013) and the two factors measured by the test. These results also coincide with studies on adolescents in Argentina (Resett, 2011, 2018). The two aforementioned dimensions have been shown to be associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in numerous studies (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018).

Regarding confirmatory factor analysis, the two-factor measurement model related -being victimized and bullying- also showed an adequate fit. For the fit to be acceptable, the CFI must be greater than .90 and the RMSEA less than .08 simultaneously (Bentler, 1992), which was the case for the present analysis. The adjustment was also close to the statistical criteria of CFI and RMSEA greater than .95 and less than .05, respectively (Hu & Blentler, 1999). Thus, the fit presented by the model was satisfactory. Such a model was much more suitable than a two-factor model with the two not associated dimensions. In this way, the results would suggest that also in Argentina, for school children, this instrument has a factorial structure similar to that detected in Anglo-Saxon and European countries: a dimension of victimization and another of carrying out bullying (Olweus, 1994, 1996). Foreign studies (Hartung et al., 2011; Kyriakides et al., 2006) reached the same conclusions, which provides some evidence of the psychometric robustness of the instrument by maintaining its factorial structure in samples from different cultures. Mainly taking into account that Argentina is a Latin nation, with less social and economic development and culturally different from that of the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic nations.

Regarding internal consistencies, these were with Cronbach's alpha of .74 for victimization and .81 for bullying. Omega's coefficient was almost similar at .75 and .83, respectively. An index between .70 and .80 is considered an adequate estimate of internal consistency (DeVellis, 2012; Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2006). These results were similar to those provided by different studies from different countries in Europe and the United States (Hartung et al., 2011; Kyriakides et al., 2006), which found, with Cronbach's alphas or item response theories, coefficients between .80-.90. Similarly, recent studies by Olweus in large Norwegian samples of almost 50,000 students found similar values (Breivik & Olweus, 2012).

Regarding the concurrent validity of both scales, it was detected that both the victimization and bullying scales correlated significantly with depression scores. It is well established that victims of bullying have more depression and this symptomatology is one of the most associated with this problem (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018). Some studies indicate that those who carry out bullying may also suffer more depression (Luk et al., 2016). One possible mechanism is that their behavioural or externalizing problems could, over time, lead them to also have internalizing problems through a “cascade” effect, that is, failure in a developmental task (healthy peer relationships) can lead to another difficulty (internalizing problems), as suggested by many scholars (e.g., Masten & Cicchetti , 2010).

On the other hand, the victimization scale correlated negatively with proximity, help, companionship, and security, and positively with conflict and balance regarding the quality of friendship. The bullying scale was positively associated with the conflict and balance scores. It is well established that both bullies and victims have greater difficulty with peers and lack social skills (Olweus, 1996). The social competence of the victims is affected by being shy or inhibited subjects, while that of the aggressors is impaired by their externalizing, dominant and aggressive pattern. However, the social competence in the friendly area of the victims was worse than those who performed it, which coincides with other studies that indicated that the psychosocial correlates of the victims are worse than that of the aggressors (Book et al., 2012). It is established that those who carry out bullying are not solitary subjects, but may have friends and affiliate with antisocial peers who, in turn, reinforce their aggression (Olweus, 1993). Some studies even indicate that those who do bullying evaluate their quality of intimate friendship as satisfactorily as that of students not involved in bullying and higher than that of those who are victimized (Resett et al., 2014).

In Argentina, studies of aggressive behaviour have been carried out, evaluating its relationship with social skills in adolescents, which have shown a significant relationship between aggressive behaviour and deficits in social skills. Negative correlations between aggressiveness and consideration of others were evaluated, as well as negative correlations between self-control and withdrawal (Caballero et al., 2018). Taking into account that bullying is a specific aggressive behaviour, and that social skills are essential for peer relationships (Contini, 2015) and specifically for friendship relationships, these mentioned findings could provide a way to understand negative correlations; significant correlations found between bullying and the positive dimensions of friendship (closeness, help and security) and the significant positive correlations found between bullying and the negative dimensions of friendship (conflict and balance).

These results on its concurrent validity are in line with findings that show friendship in childhood and adolescence as a protective factor in socialization (Rodriguez et al., 2021). Said protective factor was negatively associated with being bullied or bullying in previous studies in Argentine children (Rodriguez et al., 2015b). It should be noted that the associations detected are medium and small, according to Cohen (1988), with the exception of the association between victimization and depressive symptoms, where it was large, which is not striking since one of the most significant correlates of victimization is with respect to said symptomatology. This result was found 20 years ago in meta-analytic reviews (Hawker & Boulton, 2000, 2003), as well as in national studies (Resett, 2018). However, these effect sizes are the ones normally found in psychology because the phenomena are multi-causal. On the other hand, only in the companionship dimension, no correlation was detected with respect to bullying, which should be the subject of future studies.

For all that has been said, these findings would suggest that in the present sample this instrument would also maintain its psychometric goodness in a sample of Argentinian school children.

This research represents a contribution to the study and diagnosis of bullying in children, within the framework of the worrying increase in manifestations of aggressiveness in children and adolescents as a social emergent that must be addressed from a multifactorial perspective of aggressiveness, taking into account personal, family, educational and social factors in interaction (see Contini, 2015).

Among the limitations of this study, we can mention that it has only evaluated the variables with self-report measures, which leaves out an external view of the phenomenon, such as the view of the teacher, parents, etc., mainly on a subject such as bullying, in which information can be hidden to give socially desirable responses. On the other hand, evaluating all the variables with the same data collection technique increases the correlation of the variables by the shared variance (Richardson et al., 2009). Another limitation includes the origin of the sample, which is from a single city in Argentina and selected in a non-random way, which can bias the representativeness for the generalization of the results. On the other hand, it has been proven that the factorial structure of a test can be affected by the demographic composition of the sample and its heterogeneity in this regard (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Although a structure similar to the one reported by the authors of the instrument was detected here, future studies should randomly take samples from various areas of the country in order to generalize the results and, additionally, measure the remaining variables with other techniques, as well to self-report. On the other hand, future lines of research could work on a key variable in the interaction between bullying and peer relationships and friendship, such as social skills. Progress should also be made in the prevention of the problem, considering the quality of friendship as a protective factor in this regard, especially taking into account that friendship can be a protective factor against victimization as well as against its negative emotional correlates (Bernasco et al., 2022).

REFERENCES

Achenbach, T. (2008). Assessment, diagnosis, nosology, and taxonomy of child and adolescent psychopathology. En M. Hersen & A. Gross (Eds.), Handbook of clinical psychology (pp. 429-457). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [ Links ]

Armitage, R. (2021). Bullying in children: impact on child health. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 5, e000939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000939 [ Links ]

Arnett, J. J. (2020). Adolescencia y adultez emergente. Un enfoque cultural. Pearson. [ Links ]

Babarro, I., Andiarena, A., Fano, E., Lertxundi, N., Vrijheid, M., Julvez, J., Barreto, FB, Fossati, S. & Ibarluzea, J. (2020). Risk and protective factors for bullying at 11 years of age in a Spanish birth cohort study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(12), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124428 [ Links ]

Bentler, P. (1992). On the fit of models to covariances and methodology. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 400-404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.400 [ Links ]

Bernasco, E. L., van der Graaff, J., Meeus, W. H. J., & Branje, S. (2022). Peer victimization, internalizing problems, and the buffering role of friendship quality: disaggregating between- and within-person associations. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 51, 1653-1666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01619-z [ Links ]

Book, A.S., Volk, A. A. & Hosker, A. (2012). Adolescent bullying and personality: An adaptive approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 218-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.028 [ Links ]

Boomsma, A. & Hoogland, J. J. (2001). The robustness of LISREL modeling revisited. En R. Cudeck, S. du Toit & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation models: present and future. A festschrift in honor of Karl Jöreskog (pp. 139-168). Scientific Software International. [ Links ]

Breivik, K. & Olweus, D. (2012). An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Olweus Bullying Scale. Universidad de Bergen. [ Links ]

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometrics of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 471-485. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (2012). Structural equation modeling with MPLUS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [ Links ]

Caballero, S. V., Contini de González, N., Lacunza, A. B., Mejail, S., & Coronel, P. (2018). Habilidades sociales, comportamiento agresivo y contexto socioeconómico: Un estudio comparativo con adolescentes de Tucumán (Argentina). Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, (53), 183-203. [ Links ]

Card, N. A. & Hodges, E. V. (2008) Peer victimization among school children: correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 451-461. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012769 [ Links ]

Card, N. A., Isaacs, J. & Hodges, E. (2007). Correlates of school victimization: Recommendations for prevention and intervention. En J. E. Zins, M. J. Elias & C. A. Maher (Eds.), Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: A handbook of prevention and intervention (pp. 339-366). Haworth Press. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2a ed.). Academic Press. [ Links ]

Contini, E. N. (2015). Agresividad y habilidades sociales en la adolescencia. Una aproximación conceptual. Psicodebate, 15(2), 31-54. https://doi.org/10.18682/pd.v15i2.533 [ Links ]

Cornell, D. G. & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2010). The assessment of bullying. En S. Jimerson, S. Swearer & D. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective (pp. 265- 276). Routledge. [ Links ]

DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications. SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Espelage, D. & Swearer, S. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32, 365-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2003.12086206 [ Links ]

Facio, A., Resett, S., Mistrorigo, C., & Micocci, F. (2006). Los adolescentes argentinos. Cómo piensan y sienten. Lugar. [ Links ]

Farrington, D. P. & Ttofi, M. M. (2011). Bullying as a predictor of offending, violence and later life outcomes. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21, 90-98. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cbm.801 [ Links ]

Fehm, L. & Hoyer, J. (2004). Measuring thought control strategies: The thought control questionnaire and a look beyond. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(1), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000016933.41653.dc [ Links ]

Gaete, J., Valenzuela, D., Godoy, M.I., Rojas-Barahona, C.A., Salmivalli, C. & Araya, R. (2021). Validation of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ-R) Among Adolescents in Chile. Frontires in Psychology, 12, 578-661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.578661 [ Links ]

Hartung, C., Little, C., S., Allen, E., K., & Page, M. (2011). A psychometric comparison of two self-report measures of bullying and victimization: Differences by sex and grade. School Mental Health, 3, 44-57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000222 [ Links ]

Hawker, D. S. J. & Boulton, M. J. (2000) Twenty Years’ Research on Peer Victimization and Psychosocial Maladjustment: A Meta-Analytic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41, 441-455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629 [ Links ]

Hawker, D. S. J. & Boulton, M. J. (2003). Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. En M. E. Hertzig & E. A. Farber (Eds.), Annual progress in child psychiatry and child development: 2000-2001 (pp. 505-534). Brunner-Routledge. [ Links ]

Horn, J. L. (1965). A Rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179-185. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02289447 [ Links ]

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 [ Links ]

Kaplan, R. M. & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2006). Pruebas psicológicas: principios, aplicaciones y temas (6a ed). International Thomson. [ Links ]

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4a ed.). Guilford. [ Links ]

Kljakovic, M. & Hunt, C. (2016). A meta-analysis of predictors of bullying and victimization in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 134-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.002 [ Links ]

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Multi-Health Systems. [ Links ]

Kyriakides, L., Kaloyirou, C. & Lindsay, G. (2006). An analysis of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire using the Rasch measurement model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 781-801. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X53499 [ Links ]

Lee, T. & Cornell, D. (2009). Concurrent validity of the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Journal of School Violence, 9(1), 56-73. 10.1080/15388220903185613 [ Links ]

Li, C. H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behaviour Research Method, 48, 936-949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7 [ Links ]

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A. & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361 [ Links ]

Luk, J. W., Patock-Peckham, J. A., Medina, M., Terrell, N., Belton, D. & King, K. M. (2016). Bullying perpetration and victimization as externalizing and internalizing pathways: a retrospective study linking parenting styles and self-esteem to depression, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. Substance use and misuse, 51(1), 113-125. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.1090453 [ Links ]

Masten, A. S. & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 491-495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000222 [ Links ]

Nansel, T., Craig, W., Overbeck, M., Saluja, G., & Ruan, W. (2004). Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviours and psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 730-736. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730 [ Links ]

O'Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS Programs for Determining the Number of Components Using Parallel Analysis and Velicer's MAP Test. Behavior Research Methods, Instrumentation, and Computers, 32, 396-402. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03200807 [ Links ]

Olweus D. (1996). The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. HEMIL, Universidad de Bergen. [ Links ]

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell. [ Links ]

Olweus, D. (1994). Annotation: Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 35, 1171-1190. [ Links ]

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751-780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516 [ Links ]

Phillips, V. & Cornell, D. (2012). Identifying victims of bullying: Use of counselor interviews to confirm peer nominations. Professional School Counseling, 15, 123-131. https://doi.org/10.5330/PSC.n.2012-15.123 [ Links ]

Quintero-Jurado, J., Moratto-Vásquez, N., Caicedo-Velasquez, B., Cárdenas-Zuluaga, N. & Espelage, D. L. (2021). Association Between School Bullying, Suicidal Ideation, and Eating Disorders Among School-Aged Children from Antioquia, Colombia. Trends in Psychology, 1, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00101-2 [ Links ]

Resett, S. (2018). Análisis psicométrico del Cuestionario de Agresores/Víctimas de Olweus en español. Revista de Psicología de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 36(2), 576-602. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.201802.007 [ Links ]

Resett, S. (2021). ¿Aulas peligrosas? Qué es el bullying, el cyberbullying y qué podemos hacer. Logos. [ Links ]

Resett, S., & Mesurado, B. (2021). Bullying and cyberbullying in adolescents: a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of interventions. En P. A. Gargiulo (Ed.), Psychiatry and Neuroscience (vol. 32; pp. 445-458). Springer. [ Links ]

Resett, S., Oñate, M. E., Hillairet, A., Furlán, M., & Jacobo, C. (2014). Victimización, agresión y autoconcepto en adolescentes de escuelas medias. Investigaciones en Psicología, 19(2), 103-118. [ Links ]

Resett, S., Rodriguez, L., & Moreno, J. E. (2013). Evaluación de la calidad de la amistad en niños argentinos. Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de la América Latina, 59(2), 94-102. [ Links ]

Resett, S. (2011). Aplicación del cuestionario de agresores/víctimas de Olweus a una muestra de adolescentes argentinos. Revista de Psicología de la Universidad Católica Argentina, 13(7), 27-44. [ Links ]

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762-800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109332834 [ Links ]

Rigby, K., Smith, P., & Pepler, D. (2004). Working to prevent school bullying: Key issues. En P. Smith, D. Pepler & K. Rigby (Eds.), Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be? (pp. 1-12). Cambridge. [ Links ]

Rodriguez, L., Moreno, J. E., & Mesurado, B. (2021). Friendship Relationships in Children and Adolescents: Positive Development and Prevention of Mental Health Problems. En P. A. Gargiulo (Ed.), Psychiatry and Neuroscience (vol. 32; pp. 433-443). Springer. [ Links ]

Rodriguez, L., Resett, S., Grinóvero, M., & Moreno, J. E. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Calidad de la Amistad para niños en español. Anuario de Psicología, 45(2), 219-234. [ Links ]

Roh, B. R., Yoon, Y., Kwon, A., Oh, S., Lee, S. I., Ha, K., Shin, Y., Song, J., Park, E., Yoo, H., & Hong, H. (2015). The structure of co-occurring bullying experiences and associations with suicidal behaviors in Korean adolescents. PloS one, 10, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143517 [ Links ]

Román, M. & Murillo, J. (2011). América Latina: violencia entre estudiantes y desempeño escolar. Revista CEPAL, 104, 37-54. https://doi.org/10.18356/8d74b985-es [ Links ]

Schmidt, R. E., Gay, P., d’Acremont, M., & Van der Linden, M. (2008). A German adaptation of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Psychometric properties and factor structure. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 67(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.67.2.10 [ Links ]

Solberg, M. & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239-268. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047 [ Links ]

Steinberg, L. (2018). Adolescence. Mc Graw-Hill. [ Links ]

Swearer, S. & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the Psychology of Bullying: moving toward a social-ecological diathesis stress model. American Psychologist, 70, 344-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0038929 [ Links ]

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6a ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Martell, B. N., Holland, K. M., & Westby, R. (2014). A systematic review and content analysis of bullying and cyberbullying measurement strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(4), 423-434. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.06.008 [ Links ]

Wells, A. & Davies, M. I. (1994). The Thought Control Questionnaire: a measure of individual differences in the control of unwanted thoughts. Behavior Research and Therapy, 32(8), 871-878. https://doi. org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)90168-6 [ Links ]

Weston, R. & Gore Jr, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 719-751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345 [ Links ]

How to cite: Resett, S., Rodríguez, L. M., & Moreno, J. E. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Bullied Questionnaire for Children in Spanish. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2872. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2872

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. S. R. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; L. M. R. in a, b, c, d, e; J. E. M. in a, d, e.

Received: May 04, 2022; Accepted: March 24, 2023

text in

text in