Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.12 no.1 Montevideo maio 2018

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i1.1603

Original Articles

Repercussions of trauma in childhood in psychopathology of adult life

1Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos. Brasil vitoriawaikamp@hotmail.com fernandaserralta@gmail.com Correspondence: Vitória Waikamp, Rua Henrique Dias, 695. CEP 93214-130. Sapucaia do Sul, RS, Brasil. Fernanda Barcellos Serralta, Rua Alfredo Schuett, 927. CEP 91330-120. Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

Keywords: abuse; negligence; psychopathology; childhood; adulthood

Palavras chave: abuso; negligência; psicopatologia; infância; vida adulta

Palabras clave: abuso; negligencia; psicopatología; infancia; vida adulta

Introduction

For the World Health Organization (WHO, 2016), violence against children includes physical and/or emotional maltreatment, sexual abuse, neglect, commercial exploitation and any kind of neglect/abuse that results in actual or potential harm to health, survival, development or dignity of the child in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. According to data from this entity (WHO, 2016), a quarter of all adult people report having suffered physical abuse as a child. On average, one in five women and one in thirteen men were sexually abused during their childhood.

In Brazil, child abuse has been an increasing concern (Pires & Miyazaki, 2005). Data from the Ministry of Health (2012), for 2011, show that 14,625 notifications of domestic violence in childhood and adolescence were made. The prevalence of neglect (36%) and sexual violence (35%) was found in the 0-9 age group; physical violence (13.3%) and sexual violence (10.5%) between 10 and 14 years of age; and physical (29.3%), psychological (7.6%) and sexual (5.2%) violence between 15 and 19 years of age. In most cases, the perpetrators were identified as the parents or other relatives, as well as friends and neighbors (Ministry of Health, 2012). Intrafamily violence is potentially more detrimental to the victim, as it entails a breach of trust towards care figures, who should provide comfort, safety, and physical and psycho logical well-being (De Antoni & Koller, 2002).

From the psychodynamic point of view, trauma involves events in the individual's life that imply an amount of excitation which surpasses his/her ability to tolerate and elaborate psychically (Laplanche & Pontalis, 1996). As developing beings, children are more susceptible to this type of event (Garland, 2015). Primary care is essential for the psychic structuring and acquisition of affective regulation skills, reflexive ability and autonomy. In contrast, traumatic experiences and serious failures in early relationships can disrupt or alter the course of healthy development, leading to a lack of confidence in objects and a decrease in psychological resources. With diminished ability to symbolically represent their experiences, the pearson becomes more vulnerable to psychological distress (Garland, 2015, Fonagy, Gabbard, & Clarkin, 2013).

Trauma produces diverse consequences. Research suggest that individuals exposed to early trauma present changes in brain structure (Kristensen, Parente, & Kaszniak, 2006; Hoy et al, 2012; AAS et al., 2012), in cognitive functions (Grassi-Oliveira, Ashy, & Stein, 2008; AAS et al., 2012) and deficits in psychological functioning in general (Jonas et al., 2011).

The adverse psychological consequences of trauma permeate the life cycle. There is evidence that children exposed to trauma will be at increased risk for developing diverse clinical conditions in adulthood, such as mood disorders (Zavaschi et al., 2006; Figueiredo, Dell’aglio, Silva, Souza e Argimon, 2013; Li, D'arcy, Meng, 2016), post-traumatic stress disorder (Read, Van, Morrison & Ross, 2005; Catalan et al., 2017; Isvoranu et al., 2017), high-risk and suicidal behaviors (Lu et al., 2008), marital violence and child abuse (Roustit et al., 2009), and personality disorders (Waxman, Fenton, Skodol, Grant, & Hasin, 2014; Conceição, Bello, Kristensen, & Dornelles, 2015).

In Brazil, the Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA) was established to guarantee the rights of children and adolescents (Law 8069, 1990). Its practice, however, is progressive and many advances are needed to ensure a healthier development of the population. It is also known that the consequences of trauma and violence against children and adolescents are not limited to the health of individuals but can also retard the economic and social development of a country (WHO, 2016). The expenditure on hospitalizations of patients with mental disorders in Brazil is quite high and consumes about 32% of the National Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS budget (Mello, Mello, & Kohn, 2007). It is necessary to study the different forms of violence in childhood and also its consequences in adult life in order to know their specificities and to provide subsidies for preventive actions at different levels of health care.

The aim of this study is to investigate the repercussion of childhood trauma in the psychopathology of adult life. The study of this association is relevant given the potentially destructive impact of mental disorders on individuals' physical, emotional, cognitive and social development (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008). Thus, even if indirectly, the study is expected to contribute to raising awareness of the short-term and long-term consequences of childhood adversity in mental health, emphasizing the need for policies and programs to prevent child abuse in the country. In addition, the study intends to produce knowledge that can assist psychotherapists who treat patients suffering from psychological distress associated with the history of past trauma, not always detected.

Materials and methods

The present study has a quantitative, transversal, correlational and explanatory design (Gil, 2010) and is derived from a broader project that seeks to examine the relationship between traumatic experiences and attachment pattern in childhood with personality dysfunctions in adult life, as well as to investigate the effect of these variables on the process and on the results of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. The data collection was performed in an outpatient clinic of a training center in psychoanalytic psychotherapy located in a state capital of southern Brazil. The treatments offered are adequate to the patients' income, mostly from the lower middle-class population.

Population and Sample

The sample included all adult patients who sought care between April 2015 and October 2016. The present study included 201 patients (69.2% female and 30.8% male) from the database of the larger study to which it is linked. The mean age of participants was 32 years (SD = 12.35). The sample is distributed among different levels of education in the following proportions: Elementary education (1%); High school completed (16.5%) and incomplete (6.2%); Higher education completed (33.5%) and incomplete (35.6%); technical level (2.1%) and Postgraduate (5.2%).

Instruments

A sociodemographic questionnaire and two self-report psychometric instruments were used to collect data: Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein & Fink, 1998) and Brief Symptom Inventory - BSI (Derogatis, 1983).

The CTQ is composed of 28 questions that assess the presence of traumatic events (neglect and abuse) in childhood and adolescence. Each dimension of the instrument is composed of 5 questions with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always): emotional abuse (EA), physical abuse (PA), sexual abuse (SA), emotional neglect (EN) and physical neglect (PN). The remaining three questions form the scale of the reliability control of the responses. Reliability and validity studies attest to the good psychometric properties of the original instrument (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). In the present study, the Portuguese version was used (Grassi-Oliveira et al., 2006), which in the present sample presented reliability, evaluated with Cronbach's alpha coefficient, of 0.93 for the total scale and between 0.66 and 0.94 for the subscales.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) is an abbreviation of SCL-90 (Symptom Checklist - 90), an instrument widely used in several countries to assess symptoms of mental disorders and psychological distress (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). The BSI, like the SCL-90, can be used as a measure of therapeutic progress, as well as for clinical evaluation. It is an instrument composed of 53 items in a 5-point Likert scale that evaluate nine dimensions of symptomatology (anxiety, phobic anxiety, depression, hostility, paranoid ideation, obsessive-compulsive, psychoticism, interpersonal sensitivity and somatization) and produces general psychopathology indexes: the general symptom severity index (GSI), the total of positive symptoms and the index of positive symptoms. The GSI is the most used and reliable indicator and is considered a general measure of distress or psychological suffering derived from the symptoms. The Brazilian Portuguese version was adapted by a team of the research group headed by the second author, based on the Portuguese version of Canavarro (1999). In the present sample, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.96 for the GSI and ranged from 0.76 (psychoticism) to 0.88 (depression) in the symptom dimensions.

Data Collection Procedures

The data collection took place in the context of the major research to which this study is linked. The explanation of the research and the invitation for voluntary participation in it was made before the 1st treatment session (during the screening) by a research fellow. After signing the informed consent form, the patients answered a questionnaire to access their general symptomatology and some other sociodemographic and clinical data. At the 4th treatment session, patients and their respective therapists received a sealed envelope containing a series of self-report instruments (among them, the CTQ and the BSI specifically analyzed in this study). The instruction was that they be answered at the place of their choice and returned at the next session. Some cases were included in which the participants did not return the instruments at the 5th session and, having spontaneously expressed their intention to bring them to the next session (6th session), they did so. The remaining cases were excluded and treated as sample loss.

Results

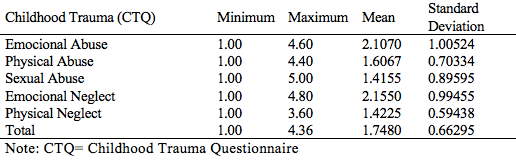

Traumatic events during childhood were examined in 201 adult patients who were initiating psychoanalytic psychotherapy at a psychotherapist training institution of this approach. From the total sample, it was verified that only 5% reported never having experienced any traumatic experience in childhood (score 1 in the Total CTQ). Emotional abuse and emotional neglect were reported by 88% of patients, while physical abuse, physical neglect and sexual abuse, respectively by 77.8%, 65% and 46% of these. No statistically significant associations were found between trauma (total CTQ and scales) and demographic variables (sex and age). The Table 1 shows the means of the traumatic events in the sample.

According to data from Table 1, the most frequent occurrences in the sample were emotional neglect (mean = 2.15, SD = 0.99) and emotional abuse (mean = 2.10, SD = 1.00), followed by physical abuse (mean = 1.60, SD = 0.70), physical neglect (mean = 1.42, SD = 0.59) and sexual abuse (mean = 1.41, SD = 0.89).

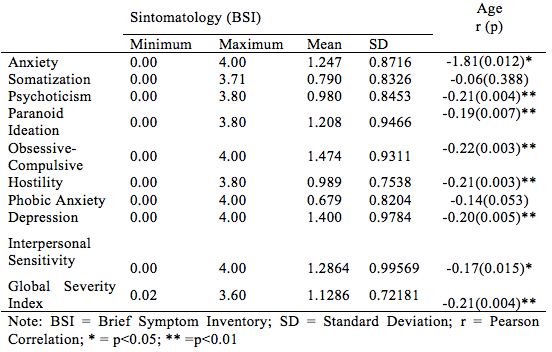

As shown in Table 2, in relation to the occurrence of psychopathological symptoms, the sample had more obsessions-compulsions (mean = 1.47, SD = 0.93) and depression (mean = 1.40, SD = 0.97). Symptoms of interpersonal sensitivity (mean = 1.28, SD = 0.99) and anxiety (mean = 1.24, SD = 0.87) were also prominent. The General Symptom Index (GSI) had an average of 1.12 (SD = 0.72).

There were no significant differences in the means of men and women in the GSI and in the symptom dimensions, except for somatization, which was higher in women (t = 2,088, p = 0.038). Age presented a significant negative correlation with several groups of symptoms and GSI.

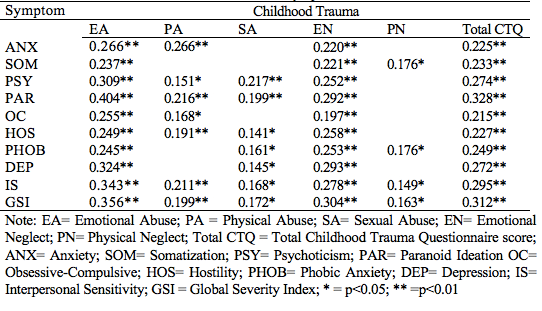

The results of the correlations between childhood traumas (evaluated by CTQ) and adult symptomatology (evaluated by BSI) show that there is a positive and significant relationship between different traumas and a wide variety of psychopathological symptoms, including general psychological distress (GSI of BSI), as in Table 3.

It is observed in Table 3 that the total trauma index presented positive and significant correlations with all symptom dimensions (between r = 0.328 (paranoia) and = 0.274 (psychoticism)) and with GSI (r = 0.312, p = 0.01). Considering each type of trauma, the strongest correlations were: sexual abuse with psychoticism (r = 0.217, p = 0.01) and with paranoid ideation (r = 0.199; p = 0.01); physical abuse with paranoid ideation (r = 0.216, p = 0.01) and interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.211, p = 0.01); emotional abuse with paranoid ideation (r = 0.404, p = 0.01), interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.343, p = 0.001), depression (r = 0.324, p = 0.01) and psychoticism (r= 0,309; p= 0.01); emotional neglect with depression (r= 0,293; p= 0,01) and paranoid ideation (r = 0.292, p = 0.01) and physical neglect with phobic anxiety (r= 0.176, p = 0.01) and somatization (r= 0,176; p= 0,01).

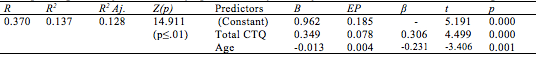

Then, a linear regression (Backward method) was performed to verify the effect of the traumas (independent variable: total CTQ) on the severity of global psychopathology (dependent variable: GSI). As the age variable was associated with symptoms, this was included as a possible predictor. Only one model was generated, indicating that, together, childhood traumas and age explain 13% of the variance of the overall symptom severity, as presented in Table 4.

Discussion

This study was carried out with 201 patients, with a mean age of 32 years and with different levels of education, attended in an outpatient of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. In general, total trauma (total CTQ) and general symptom severity (GSI) indicators had stronger positive correlations than those found between types of trauma and symptom-specific groups. These findings suggest that the psychological distress derived from the current symptomatology of these patients is positively associated with the occurrence of childhood traumas. In addition, the findings indicate that all the traumatic dimensions experienced by patients in their child's life (emotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, and sexual abuse) have significantly influenced the level of their current psychological distress.

The results are in agreement with the post-Freudian psychoanalytic literature which highlights the importance of a safe and healthy primary environment provided by empathic, protective and non-invasive caregivers for the subsequent satisfactory psychic development (Winnicott, 1987/2012; Kohut, 1984; Fonagy et al, 2013; Fonagy, 2004). The associations found also corroborate the findings of many studies that found positive relationship between traumatic events in childhood and various clinical conditions and psychopathological symptoms in the adult (Roustit et al., 2009; Figueiredo et al. 2013; Breslau et al., 2014; Waxman et al., 2014; Isvoranu et al., 2017).

It is also worth noting the consistent relationship between childhood traumas and supposedly more serious psychopathological symptoms such as psychoticism, interpersonal sensitivity, paranoid ideation and depression, which is consistent with research findings of the association between early traumas and personality disorders (Waxman et al., 2014) and psychoses (Catalan et al., 2017; Isvoranu et al., 2017).

According to Siegel (2005), when studying more serious psychopathologies Heinz Kohut found that when someone is deprived of internalized object relations, is more predisposed to the formation of psychotic symptoms. These symptoms would be the individual's attempt to recover contact with lost objects. To Fonagy (2004), the typical symptoms of patients with severe personality disorders arise from the activation of their insecure attachment system, which, in turn, results from adverse experiences in childhood.

Considering the different syndromes evaluated by the BSI, the results indicate that obsessions-compulsions and depression were the most prominent symptoms. These symptoms are most characteristically found in neurotic personality structures (McWilliams, 2014), consistent with what would be expected in a general psychoanalytic psychotherapy outpatient clinic. Although Freudian theory (1905/1996) indicates that neurotic patients may distort (by fantasy) events of their former life, especially those related to oedipal desires and anxieties, the results of this study suggest that the occurrence and effect of childhood traumas should not be neglected in the life of these patients. Although the retrospective evaluation of trauma is an important limitation of this study, the associations between early trauma and psychopathological symptoms in adults are consistent and are in the same direction as the current literature on the subject.

It is noteworthy that most patients reported to some degree traumatic experiences in childhood. Emotional neglect was the most reported situation, followed by emotional abuse. These experiences refer to what Bowlby (1981) characterized as "mother deprivation" and Winnicott (1983), as the absence of a "good enough environment", that is, the inability of the environment to promote affection, safety and protection of the child. There is evidence that this type of violence is the most frequent (Koller & Habigzang, 2012) and the one that produces the most negative effects regarding psychopathology (Nurius, Logan-Greene, & Sara Green, 2012). However, the lack of physical evidence favors that the psychological violence is not immediately identified by the professionals, being thus underestimated in demographic surveys (Koller & Habigzang, 2012). Findings from this study suggest that health care professionals should pay attention to the sometimes silent presence of the history of neglect and psychological abuse of their patients.

The amplitude and intensity of the infantile traumas found in this sample reinforce the hypothesis of the relation between the primary failures in emotional care and the psychological distress of the adult. They also point out that, although sexual abuse and physical abuse may not be a rule among patients seeking psychotherapy, they are also not exceptions, since most patients report having a history of physical abuse and nearly half, of sexual abuse. These indices exceed WHO estimates (2016) in the overall general population, suggesting that among the clinical population rates of child abuse and violence are even higher.

As a result of simple linear regression, childhood traumas, along with age, account for 13% of the overall severity variance of psychopathology, indicating that the greater perceived intensity of adverse childhood experiences and less age account for the level of psychological distress derived from symptoms of the adult patient. This finding confirms the initial hypothesis of the research that infant traumas would be predictive of psychopathology in the adult individual. The effect of interaction with age deserves further investigation in other studies and suggests that maturity contributes to the reduction of adverse effects of early negative experiences.

This study verified the adverse effect of infantile traumatic experiences on psychological distress and psychopathology in adult life of patients who were initiating psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Their results point to the relevance of childhood traumatic experiences in individuals' mental health. Thus, in addition to contributing to alert psychotherapists to significant levels of past traumatic situations in their patients, the study may contribute to elicit greater reflection on the need for preventive actions in childhood and adolescence.

Despite these contributions, the study has many limitations. It is a cross-sectional, naturalistic study in a heterogeneous sample of patients. The approach was correlational and the explanatory analysis was exploratory, and other variables that may interfere with the relationships found, such as mentalization capacity (reflective function), which in other studies moderated both the relation between the combination of different traumas in childhood and personality disorders as among these adversities and psychological distress in adult psychiatric patients (Chiesa & Fonagy, 2014). In addition, the present study used self-report measures, which may favor a bias of contamination in the reporting of maltreatment experiences, due to memory and/or mental health problems of the participants (Hardt & Rutter, 2004).

Conclusion

A considerable number of patients seek psychological care in adult life for current problems that may have a direct or indirect causal relationship with traumas of the past. The findings of the present study, conducted with patients who were initiating psychoanalytic psychotherapy, are in line with the literature that affirms the importance of past events in further psychological development and with research that consistently indicates the relationship between trauma in childhood and different psychopathological disorders in adult life.

Based on the findings of this study, it is suggested that psychotherapists and other mental health professionals examine the investigation of the past life of their patients and pay attention to the identification of past traumatic events that may be related to the current psychological suffering. In addition, it is hoped that the research will stimulate other studies that together contribute to the development of effective preventive and intervention strategies that favor the mental health of children, adolescents and adults.

How to cite this article:

Waikamp, V., & Serralta, F. B. (2018). Repercussões do trauma na infância na psicopatologia da vida adulta.Ciencias Psicológicas,12(1), 137-144. doi: 10.22235/cp.v12i1.1603

Referências

Aas, M., Steen, N. E., Aminoff, S.R., Lorentzen, S., Sundet, K., Andreassen, O. A., & Melle, I. (2012). Is cognitive impairment following early life stress in severe mental disorders based on specific or general cognitive functioning? Psychiatry Research,198(3), 495-500. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.045 [ Links ]

Bernstein, D., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire: a retrospective self-report manual Manual. San Antonio, TX. [ Links ]

Bowlby, J. (1981). Cuidados maternos e saúde mental (1a ed.). São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Breslau, N., Koenen, K. C., Luo, Z., Agnew-Blais, J., Swanson, S., Houts, R. M.,... & Moffitt, T. E. (2014). Childhood maltreatment, juvenile disorders and adult post-traumatic stress disorder: a prospective investigation.Psychological medicine,44(9), 1937-1945. [ Links ]

Canavarro, M. C. (1999). Inventário de Sintomas Psicopatológicos - B.S.I.. In M. R. Simões, M. M. Gonçalves, & L. S. Almeida (Orgs.). Testes e provas psicológicas em Portugal (Vol. 2, pp. 95-109). Braga, Portugal: APPORT/SHO. [ Links ]

Catalan, A., Angosto, V., Díaz, A., Valverde, C., de Artaza, M. G., Sesma, E., . . . Gonzales-Torres, M. A. (2017). Relation between psychotic symptoms, parental care and childhood trauma in severe mental disorders. Psychiatry Research, 251, 78-84. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.017 [ Links ]

Chiesa, M., Fonagy, P. (2014). Reflective function as a mediator between childhood adversity, personality disorder and symptom distress. Personality and Mental Health, 8 (1) 52 - 66. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1245. [ Links ]

Conceição, I. K., Bello, J. R., Kristensen, C. H., & Dornelles, V. G. (2015). Sintomas de TEPT e trauma na infância em pacientes com transtorno da personalidade bordeline.Psicologia em Revista, 21(1), 87-107. Recuperado de: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/per/v21n1/v21n1a07.pdf [ Links ]

De Antoni, C. & Koller, S. H. Violência doméstica e comunitária. In M. L. J. Contini et al. (Orgs.). (2002). Adolescência & psicologia: concepções, práticas e reflexões críticas. Conselho Federal de Psicologia, 85-91. [ Links ]

Derogatis, L.R. (1983). SCL-90: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual-I for the Revised Version and other Instruments of the Psychopathology Rating Scale Series. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit. [ Links ]

Derogatis, L.R. , & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595-605. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [ Links ]

Figueiredo, A. L., Dell’aglio, J. C., Silva, T. L., Souza, L. D., & Argimon, I. L. (2013). Trauma infantil e sua associação com transtornos do humor na vida adulta: uma revisão sistemática.Psicologia em Revista, 19(3), 480-496. Recuperado de: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/per/v19n3/v19n3a10.pdf [ Links ]

Fonagy, P. (2004). Early life trauma and the psychogenesis and prevention of violence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036, 181-200. doi: 10.1196/annals.1330.012 [ Links ]

Fonagy, P., Gabbard, G.O., & Clarkin, J.F. (Orgs.). (2013). Psicoterapia psicodinâmica para transtornos da personalidade: um manual clínico. Porto Alegre, Brasil: Artmed. [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1996). Fragmento da análise de um caso de histeria. Edição Standard Brasileira das Obras Psicológicas Completas de Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 19-116). São Paulo, Brasil: Imago. (Obra original publicada em 1905) [ Links ]

Garland, C. (2015). Abordagem psicodinâmica do paciente traumatizado. In C. L. Eizirik, R.W. Aguiar, & S.S. Schestatsky, (Orgs.). Psicoterapia de orientação analítica: fundamentos teóricos e clínicos. (3a. ed.). Porto Alegre, Brasil: Artmed . [ Links ]

Gil, A. C. (2010). Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. (5a. ed.). São Paulo, Brasil: Atlas. [ Links ]

Grassi-Oliveira, R., Stein, L. M., & Pezzi, J. C. (2006). Tradução e validação de conteúdo da versão em português do Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.Revista de Saúde Pública, 40(2), 249-255. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102006000200010 [ Links ]

Grassi-Oliveira, R., Ashy, M., & Stein, L. M. (2008). Psychobiology of childhood maltreatment: effects of allostatic load? Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 30(1), 60-68. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462008000100012 [ Links ]

Hardt, J. & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260-273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [ Links ]

Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature.Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(8), 797-810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [ Links ]

Hoy, K., Barrett, S., Shannon, C., Campbell, C., Watson, D., Rushe, T., . . . Mulholland, C. (2012). Childhood trauma and hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(6), 1162-1169. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr085 [ Links ]

Isvoranu, A., Van Borkulo, C. D., Boyette, L. L., Wigman, J. T., Vinkers, C. H., & Borsboom, D. (2017). A network approach to psychosis: pathways between childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin , 43(1), 187-196. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw055. [ Links ]

Jonas, S., Bebbington, P., McManus, S., Meltzer, H., Jenkins, R., Kuipers, E., ... & Brugha, T. (2011). Sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in England: results from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey.Psychological medicine ,41(4), 709-719 doi:10.1017/S003329171000111X. [ Links ]

Kohut, H. (1984). How does analysis cure? Chicago, Illinois: University Of Chicago Press Paperback. [ Links ]

Koller, S. H., & Habigzang, L. F. (2012). Violência contra crianças e adolescentes: teoria, pesquisa e prática. Porto Alegre, Brasil: Artmed . [ Links ]

Kristensen, C. H., Parente, M. A., & Kaszniak, A. W. (2006). Transtorno de estresse pós-traumático e funções cognitivas. Psico-USF, 11(1), 17-23. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712006000100003. [ Links ]

Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J. B. (1996). Vocabulário da Psicanálise. São Paulo, Brasil: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Lei n. 8069, de 13 de julho de 1990 (2002). Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente (ECA). Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Li, M., D'arcy, C., & Meng, X. (2016). Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions.Psychological medicine ,46(4), 717-730. doi:10.1017/S0033291715002743 [ Links ]

Lu, W., Mueser. K.T., Rosemberg, S. D., & Jankowski M.K. (2008). Correlates of adverse childhood experiences among adults with severe mood disorders. Psychiatric Services, 59(9), 1018-1026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.9.1018. [ Links ]

Mcwilliams, N. (2014). Diagnóstico psicanalítico: entendendo a estrutura da personalidade no processo clínico. (2a. ed.). Porto Alegre, Brasil: Artmed . [ Links ]

Mello, M. F., Mello A. A. , & , Kohn R. (Orgs.). (2007). Epidemiologia da saúde mental no Brasil. Porto Alegre, Brasil: Artmed . [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde. Abuso sexual é o 2º maior tipo de violência. (2012). Recuperado em 10 de Julho, 2017, de Recuperado em 10 de Julho, 2017, de http://www.blog.saude.gov.br/index.php/promocao-da-saude/30223-abuso-sexual-e-o-segundo-maior-tipo-de-violencia . [ Links ]

Nurius, P. S., Logan-Greene, P. L., & Green, S. (2012). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) within a social disadvantage framework: distinguishing unique, cumulative, and moderated contributions to adult mental health. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 40(4), 278-290. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.707443. [ Links ]

Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS). (2016). Maus tratos infantis. Recuperado de: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/ factsheets/fs150/en/ [ Links ]

Pires, A., & Miyazaki, M.(2005). Maus-tratos contra crianças e adolescentes: revisão da literatura para profissionais da saúde. Arquivos de Ciências da Saúde, 12(1), 42-49. [ Links ]

Read, J., Van Os, J., Morrison, A. P., & Ross, C. A. (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 330-350. [ Links ]

Roustit, C., Renahy, E., Guernec, G., Lesieur, S., Parizot, I., & Chauvin, P. (2009). Exposure to interparental violence and psychosocial maladjustment in the adult life course: advocacy for early prevention. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(7), 563-568. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077750. [ Links ]

Siegel, A. (2005). Heinz Kohut e a Psicologia do Self. São Paulo, Brasil: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Waxman, R., Fenton, M. C., Skodol, A. E., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. (2014). Childhood maltreatment and personality disorders in the USA: Specificity of effects and the impact of gender.Personality and Mental Health , 8(1), 30-41. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1239 [ Links ]

Winnicott, D. W. (1983). O ambiente e os processos de maturação: estudos sobre o desenvolvimento emocional. Porto Alegre, Brasil: Artmed . [ Links ]

Winnicott, D.W. (2012). Os bebês e suas mães. (5a. ed.). São Paulo, Brasil: Martins Fontes. (Obra original publicada em 1987) [ Links ]

Zavaschi, M. L., Graeff, M. E., Menegassi, M. T., Mardini, V., Pires, D. W., de Carvalho, R. H., . . . Eizirik, C. L. (2006). Adult mood disorders and childhood psychological trauma. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 28(3), 184-190. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462006000300008 [ Links ]

Received: July 17, 2017; Revised: December 15, 2017; Accepted: March 19, 2018

texto em

texto em