1. Introduction

The Middle-Late Permian continental fossil record is best documented in South America from the Brazilian Rio do Rasto Formation (Guadalupian-Lopingian boundary, Paraná Basin), where an association of continental tetrapods, including archegosaurid temnospondyls, pareiasaurs, and basal therapsids were described from the Morro Pelado Upper Member1)(2.

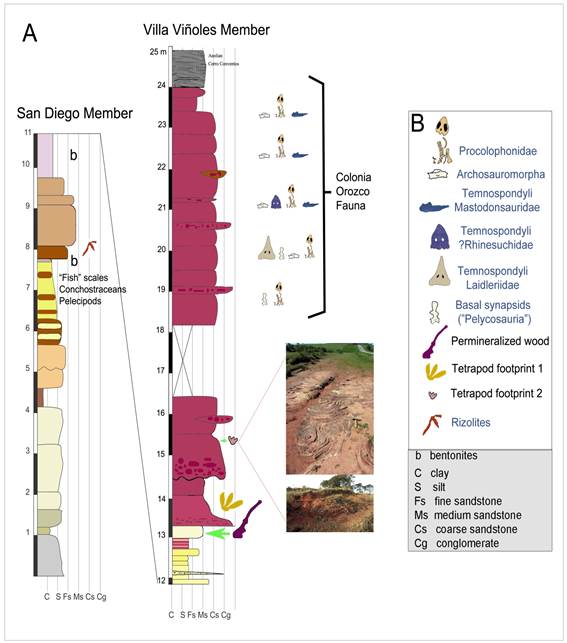

The Yaguarí Formation of Uruguay (sensu Ferrando & Andreis, 1986) has been historically considered as the stratigraphic equivalent of the Rio do Rasto Formation3)(4, but due to the absence of fossil tetrapods in the former, this correlation has been mainly based on lithological similarities rather than on biostratigraphic evidences. Until now, fossils of tetrapods were absent in the Yaguarí deposits, in contrast with the abundance of tetrapod skeletons discovered in the upper Morro Pelado Member of the Rio do Rasto Formation (for example Langer and others1, Dias and Barbena5, Malabarba and others6, Cisneros and others7, Dias-da-Silva8, Iannuzzi and others9). The only described fossils from the deposits currently assigned to the Yaguarí Formation come from the pelitic lower section, a marginal deltaic sedimentation with influence of the open sea4. A fossil association containing bivalves such as cf. Pyramus cowperesoides10)(11, conchostracans of the species Cyzicus (Euestheria) falconeri12)(13, and isolated scales of actinopterygian, sarcopterygian (coelacanthids) and possible acanthodian affinities has been described for the pelitic facies (mostly limestones and fine-grained sandstones) at the locality denominated as Baeza, situated 6 km NNE to the Melo City, which so far constituted the most fossiliferous site of the lower San Diego Member of the Yaguarí Formation11)(13. However, all these fossils have apparently a scarce or no biostratigraphic value due to their endemic distribution. Other fossils known from the Yaguarí Formation are plant remains, preserved as carbonized compressions and impressions of leaves, mostly representing taxa typical of the Glossopteris Flora14)(15 and well-preserved permineralized wood fragments that are more frequently associated to the sandstone facies16)(17)(18 (Figure 1).

1.1. Geological, stratigraphic, and paleoenvironmental background

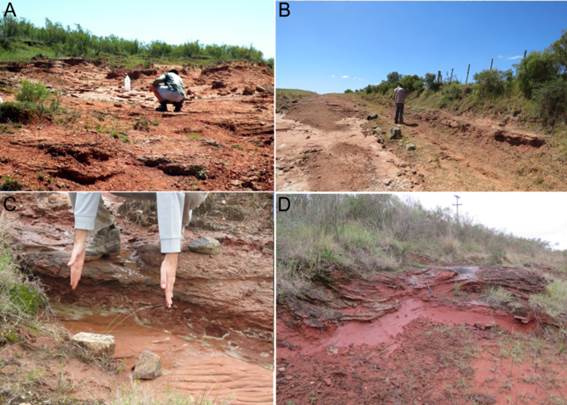

The Cerro Largo Group4)(20) in the Norte Basin represents a Late Carboniferous to Middle/Late Permian sequence that documents the gradual passage from estuarine and fluvioglacial to periglacial deposits of the San Gregorio and Tres Islas formations, to the establishment of a continental sedimentation including deltaic, fluvial, and eolian facies of the Yaguarí Formation (YF). Earlier researches have regarded these strata of the YF as formed by two members: the lower San Diego and the upper Villa Viñoles21. The lower San Diego Member is characterized by the presence of mudstones and siltstones of variegated colors (white, green and brownish), while the upper section (Villa Viñoles Member) is dominated by reddish fine-to medium-grained sandstones that represent continental fluvial, lacustrine and eolian paleoenvironments4. The uppermost part of the Villa Viñoles Member has been considered by Falconer16 as a distinct stratigraphic unit denominated Buena Vista Formation (BVF). This characterization of the BVF was based on the presence of several levels of pebbly intraformational conglomerates intercalated between the red sandstones22. This proposal has been later followed by most authors (for example, Bossi and Navarro4, Goso and others23, De Santa Ana and others24). Nevertheless, having studied the complete sequence, we considered the lithostratigraphic proposal of Elizalde and others21 as the best supported for these deposits, mainly because among other features, the intraformational conglomerates have been lost by mechanical destruction during highway constructions and concomitant rapid erosion, as it is currently observed. This issue has increased the difficulties to distinguish in the field the deposits previously identified as the BVF from those corresponding to the uppermost section of the Villa Viñoles Member of the Yaguarí Formation (Figure 2).

Taking into account some lithological similarities between the Yaguarí and the Rio do Rasto formations, as well as between the BVF and the Sanga do Cabral Formation (SCF), the lithostratigraphic correlation of these units has been supported by previous authors, despite the absence in Uruguay of the Lower Triassic index fossils found in the SCF of Brazil (see Dias-da-Silva and others25). According to this lithostratigraphic scenario, the Yaguarí Formation would be representative of the Late Permian, and the BVF would correspond to the Early Triassic4)(26. Therefore, although tetrapod index fossils were then absent in Uruguay, the limit between these units was considered a chronostratigraphic boundary (see Piñeiro11). More recently, the intraformational conglomerates of the BVF resulted to be the most fossiliferous levels of the overall sequence, but their fossil content is not equivalent to that reported for the Sanga do Cabral Formation of Brazil11)(13)(27)(28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34 (Figure 1). Moreover, based on paleomagnetic and absolute dating a Late Guadalupian-Early Lopingian age (Middle-Late Permian) for the YF and the BVF has been proposed19, which is also supported by the fossil content throughout the sequence.

In this contribution, we describe an enigmatic fossil wood stem recently found in light colored sandy and partially calcareous levels from the base of the upper Villa Viñoles Member of the YF (sensu Elizalde et al., 1970). We also include a preliminary study of several footprints that constitute the first evidence of the presence of vertebrates in these continental strata, found below the fossiliferous intra-conglomerates of the BVF. These new fossils will potentially contribute to a better calibration of the age and paleoenvironmental interpretation of the sequence.

Figure 1: Simplified stratigraphic profile of the Middle-Late Permian Yaguarí Formation sensu Elizalde et al., 1970, showing the relative position of the fossils yielded by these deposits (San Diego and Villa Viñoles members), including that of the permineralized wood and the tetrapod footprints described herein. Photographs show the convolute sedimentary structures present in the site where the first small footprint was found. From Ernesto and others19, modified.

Figure 2: Intraformational conglomerates of the Yaguarí-Buena Vista sequence (Middle-Late Permian, Uruguay). A. A typical outcrop of the Buena Vista Formation preserving fossiliferous intra-conglomerates. B. The same site shown in A after the loss of conglomerates by mechanical destruction using caterpillars. C and D represent outcrops assigned to the upper Villa Viñoles Member of the Yaguarí Formation with unfossiliferous conglomerate levels and absence of them, respectively

2. Materials and results

The plant material described herein consists of a three-dimensionally preserved siliceous permineralized branch, 55-cm-long (Figure 3), which is stored at the novel Paleontological Collection, associated with the School of Agronomy herbarium, in Montevideo, Uruguay (Fagro). It was collected from a fine-grained sandstone bed with intercalated siltstones and calcareous levels in the middle section of the Yaguarí Formation (Figure 1). These levels are lithologically similar and possible contemporaneous to deposits in a neighbor locality where a purple colored bentonitic layer was found, suggesting a volcaniclastic influence in the siliceous preservation of the fossil in a lacustrine paleoenvironment (see Trümper and others35).

2.1. The controversial study for the identification of Fagro 0001

At first look, this specimen seemed to be the first tetrapod bone found in the Yaguarí Formation. Its color and general structure (e.g., its dorso-ventrally compressed section, the aspect of its surface, etc.) suggested that it might have been a tetrapod rib.

Nevertheless, after the complete extraction from the sedimentary matrix, the specimen looked similar to a sphenacodontid vertebra with a long dorsal spine, although we noted that the supposed “vertebral body” was not as symmetric as expected (even if asymmetries are commonly observed in some Dimetrodon vertebrae). Alternatively, we also hypothesized that it could have been a fossil stem. Thus, we compared this specimen with images of dorsal vertebrae of different Dimetrodon species kindly provided by Dr. Frederik Spindler, but the shape and diagnostic structures appeared to be ambiguous (Figure 4).

Therefore, we started to analyze the microanatomy of the specimen to know more about its nature. Petrographic transversal thin sections were analyzed using a binocular microscope OLYMPUS SZ 61 TR, as well as an AXIO Imager 2, light microscope and several photographs were obtained using a ZEISS Axio digital camera. However, since the resulting information was not as clear as we expected, we decided to study the specimen with SEM to obtain additional data. SEM images and analyses of the chemical composition (e.g., spectroscopic analyses; EDS) were performed. Finally, we sent all the collected information to specialists in microanatomy, including two paleobotanists, asking for their help to find diagnostic characters that would assure a precise identification of this enigmatic fossil.

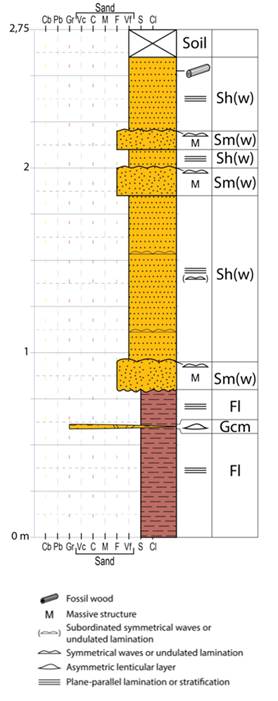

2.2. Description of the stratigraphic section that yielded the specimen Fagro 0001

The outcrop is a 2-m-deep and 6-m-wide gullet at the side of an unpaved road (Figure 5). Its stratigraphic description is as follows (see Figure 6):

Fl. Weakly laminated red to greenish grey mudstone.

Gcm. Red intraformational conglomerate with mud clasts, massive. Occurs in ripple-shaped lenses.

Sm(w). Greenish grey to beige fine-grained sandstone, with massive internal structure, and symmetrical waves at the top. Cementation by calcium carbonate.

Sh(w). Reddish to beige very fine-grained micaceous sandstone, with plane-parallel lamination. Millimetric, dispersed and discontinuous levels of fine-grained sand with symmetrical wave ripple lamination. Incipient unidirectional current ripple lamination is also present.

Facies Fl indicates deposition by sediment fallout from suspension, under mainly oxidant conditions36. Occasionally, relatively stronger currents occurred that could erode unconsolidated mud, forming ripple-shaped lenses of facies Gcm. The mudstone is erosively overlain by facies Sm(w), which has internal massive structure, indicating gravity or hyperpycnal flows37)(38, or lack of grain-size contrast. However, the symmetrical wave forms at the top are evidence of oscillatory current action. Beds of the Sm(w) facies are usually thinner and alternate with the thicker beds of the Sh(w) facies. The Sh(w) facies is dominated by deposition by fallout of very fine-grained sand from suspension, however, oscillatory and unidirectional flows were also registered.

Figure 3: Fagro 0001. Photograph of the permineralized siliceous branch found in situ at the base of the upper member of the Yaguarí Formation (Middle-Late Permian) of Uruguay after preparation

Figure 4: Comparative studies of the specimen Fagro 0001 with vertebral centra and ribs of Dimetrodon (squared at the lower right corner of the figure)

The facies succession is here interpreted as representing a lake, followed by the emplacement of a small or distal delta37. Lake deposition was subject to occasional relatively stronger currents, as evidenced by facies Gcm. Ripping up of clasts might have been facilitated by subaerial exposure39, however, desiccation cracks were not observed. Deposition of facies Sm(w) would represent moments of greater sediment discharge, generating hyperpycnal flows37. After the hyperpycnal plume settled, the top of the sediment was reworked by the oscillatory waves of the lake surface. This more “episodic” deposition alternated with the more “ordinary” deposition of the Sh(w) facies, which had a more continuous subordinate influence of oscillatory waves, and also more subordinately, weak unidirectional currents. The fossil wood was found within the Sh(w) facies, indicating that it probably sunk after floating downstream and reaching the delta. An alternate interpretation might be that of a floodplain, followed by a succession of crevasse splays. However, characteristic structures such as climbing ripples were not observed.

These settings are consistent with previous paleoenvironmental interpretations of the Yaguarí Formation24, and also with the inferred paleoenvironments of its Brazilian counterpart, the Rio do Rasto Formation, and, more specifically, the upper Morro Pelado Member40)(41.

Contrary to most of the described fossil wood from the Yaguarí Formation sensu Elizalde et al., 1970, the specimen Fagro 0001 was found within the strata and thus the level of its provenance can be determined with certainty (Figures 5-6).

Figure 5: A and B. Panoramic views of the outcrop where the permineralized stem was found (head arrow in B points to the specific level). C. Detailed view of the specimen Fagro 0001 described herein

Figure 6: Columnar section describing lithologies of the outcrop where the fossil wood was found. Facies code follow the recommendations of Miall36, modified. Refer to the text for facies description

2.3. The first tetrapod footprints found in the Villa Viñoles Member

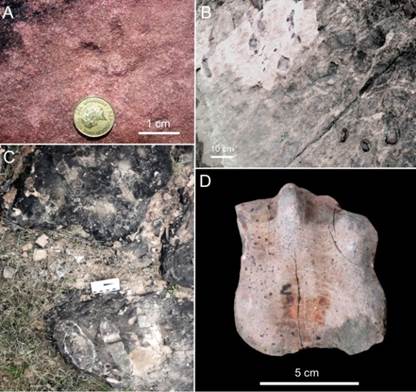

Several years ago, a small footprint was found in fine-to-medium grained red sandstones outcropping along the National Route N° 44. Fluvial-eolian interaction paleoenvironments are suggested for the deposition of these facies, where tabular sheets of the eolian sandstones can be seen intertongued with flood surfaces and overbank‐interdunes. Convolute sedimentary structures, interpreted as possible sismites (2016 conversation with César Goso; unreferenced), were also observed in the print bearing site (Figure 7A-B), being these lithologies consistent with those referred by the lower-middle section of the Villa Viñoles Member of the Yaguarí Formation4)(21)(24. The isolated footprint (Figures 1, 8A), about 1-cm-long and 1.5-cm-wide, is preserved in concave epirelief.

Only the three lateral digits III-V are clearly impressed, whereas the digit II impression is very shallow and that of digit I is not preserved. Digit proportions are II<V≤III≤IV. The digits imprints are thick and end in rounded terminations. Digit V is preserved as a rounded tip. The palm/sole impression is short, wider than long and incompletely impressed. The digit divarication is relatively high, especially between digit III-V impressions. The median-lateral part of the track is more deeply impressed than the medial part. All these features are consistent with the ichnogenus Capitosauroides Haubold, as revised by Buchwitz and others42. Because of the fragmentary nature of the material, we assign this track to cf. Capitosauroides isp. This ichnogenus has been recently attributed to therocephalian therapsid producers43.

More recently, larger footprints were found on very fine-to-middle grained fluvial white and pink to reddish sandstones, 7 m in thickness, with ripple mark stratification (Figure 7C). Five tabular centimetric sand sheets are inclined 15° and 35° N and 30° E by an inverse failure of N55W direction. Each sheet is composed by fine-to-very fine grained sandstones with fine ondulating stratification at the base, which grade to fine-to-medium grained layers with symmetrical to asymmetrical ripple marks at the top, where the footprints were preserved. These structures suggest a marginal paleoenvironment with weak currents or normal wave oscillation, and asymmetrical ripples that could indicate periods of floods and paleocurrents or stronger wind action.

The large footprints, including the natural cast of a footprint of a medium-sized animal, are preserved in a slightly lower stratigraphic position compared to the first finding (Figures 1, 8B-D). The largest observed footprints are more than 20-cm-long and 30-cm-wide, and are preserved in concave epirelief. Only digit impressions or tips can be recognized. The digit impressions are long and can be distally curved medially, sometimes only the digit tips are preserved. The digit divarication is relatively high, and the tracks seem to be ectaxonic, with the impression of digit IV being the longest. The morphology and size of these footprints match the characteristics of the ichnogenus Karoopes Marchetti et al. Because of the poorly-preserved and incomplete material, we assign these footprints to cf. Karoopes isp. This ichnogenus has been attributed to gorgonopsian therapsid producers43. The isolated track preserved in convex hyporelief is a 7-cm-long and 5-cm-wide footprint with a broad sole and tightly-packed digit imprints, of which only the rounded distal part is visible. The digit length markedly increases between digit I-III impressions. The digit IV impression is probably broken distally, and the digit V impression is not visible. Nevertheless, the observed morphological features match those of a right pes of Pachypes Leonardi et al. (Valentini and others44, Marchetti and others45). Due to the poor preservation of the specimen, we assign this footprint to cf. Pachypes isp. This ichnogenus has been attributed to pareiasauromorph parareptiles46. Most the footprints could not be collected and thus they were left in the field, where unfortunately, the outcrop bearing the small footprint was very damaged by caterpillar machines.

3. Discussion

3.1. Preliminary brief description of the gymnosperm wood

The performed primary anatomical and microanatomical studies through the thin sections revealed that Fagro 0001 is a light colored monoxilic and picnoxilic gymnosperm silicified wood, with tracheids very small in diameter (10 µm or less), uni- to biseriated rays and well-developed secondary xylem with scarce and poorly marked growing rings (Figure 9).

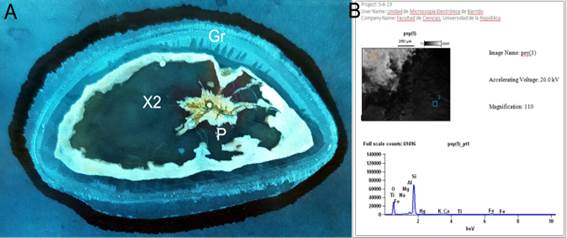

The stem has an oval cross section, possibly due to compression (Figures 4, 10A). The small pith and the primary xylem might be preserved (Figure 9 A). The cell walls are thin and their different size, although always small, and morphology of the tracheids in the secondary xylem (Figure 9 C) turn the structure a little sloppy. True growth lines are sparse and very poorly marked and false rings can be observed (Figures 9 B-D). SEM (EDS) analyses availed the silicified nature of the studied wood, although it is possible that a small part of the original components still remains (Figure 10B).

The small size of the tracheids and their distorted arrangement (shear zones, see Figure 7C) initially hampered the identification of this specimen as a plant (2019, conversation with Jean Broutin and Ronny Rößler; unreferenced). However, from an exhaustive revision of the available related bibliography, we could find in our material microanatomical similarities very close to those described for the taxa associated to the “Dadoxylon-Araucarioxylon” complex47)(48)(49)(50)(51.

Figure 7: A. General view of the outcrop where the small footprints were found. Convolute stratification, probably suggesting seismic activities, can be seen at the left of the 35-cm-long hammer. B. Detail of the footprint bearing sandstone surface (orange arrow). C. General view of the outcrop that yielded the big footprints (pink arrows point to the fossiliferous levels)

Figure 8: Tetrapod footprints from the lower Villa Viñoles Member. A. cf. Capitosauroides isp. Isolated right footprint, concave epirelief. B-C. cf. Karoopes isp. Isolated and incomplete tracks, concave epirelief. D. cf. Pachypes isp. Isolated right pes footprint, convex hyporelief

Figure 9: Microanatomical structure of transversal thin sections of the studied permineralized wood (Fagro 0001) from the Yaguarí Formation (Middle-Late Permian of Uruguay). A. Pith (P), possible primary xylem (X1) and secondary xylem (X2). B. False rings (Fr) and growing rings (Gr). C. The variable morphology and small size of the tracheids can be observed from the image as well as through the uniseriate rays (white arrows). D. A growth ring (Gr) showing possible shear zones and a false ring in the earlywood

Figure 10: A. Transversal view of the stem in the performed thin section. B. SEM EDS to show the chemical composition of the permineralized wood (Fagro 0001), where silicification is proved to have been the taphonomic process that preserved this specimen. Abbreviations: P, Pith; Gr, Growth ring; X2, Secondary xylem

3.2. Stratigraphic characterization for the Yaguarí and Buena Vista formations and the resulting biostratigraphic relationships

The results obtained by the paleomagnetic analyses by Ernesto and others19, along with recently performed detailed sedimentological and stratigraphic studies made in the YF (sensu Elizalde et al., 1970) within the framework of two researching project grants (see the Acknowledgements section), allowed the revision of previous biostratigraphic hypotheses proposed for these strata and their correlatives in Brazil.

The Rio do Rasto Formation, considered as deposited in a deltaic paleoenvironment with lacustrine and fluvial influences, crops up in the Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul states, grading upwards to eolian deposits of the Pirambóia Formation40. An identical stratigraphic arrangement is observed in Uruguay, where the eolian deposits of the Cerro Conventos Member (upper member of the BVF according to De Santa Ana and others24 and De Santa Ana52) cover the upper part of the Villa Viñoles Member. Therefore, the uppermost red sandstones of the YF with the intercalated intraformational conglomerates (representing the BVF sensu Ferrando & Andreis, 1986) should not be correlated with the Lower Triassic SCF, which crops in the Rio Grande do Sul state overlying the eolian deposits of the Pirambóia Formation.

3.3. A new representative of the Dadoxylon-Araucarioxylon complex in the Permian of Uruguay

Progymnosperm (ferns and lignophytes) floristic diversification started during the Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous and it has been described through records from North America and Europe. However, the continuity of such floras during the Late Carboniferous and the Permian period is poorly known. Recently, several discoveries of permineralized ferns and lignophytes have been reported for the Missisipian Dukabrook Formation of Central Queensland, Australia, associated to a freshwater fauna that includes fish remains and tetrapods51)(53. The most striking controversy around these discoveries was the possible taxonomic affinities of the new Australian silicified wood to genera such as Pitus and Dadoxylon, which were conspicuous taxa in Mississipian floras from Europe and North America. Something similar can be occurring with the herein described enigmatic wood from the upper member of the Yaguarí Formation, whose microanatomical structuration is very similar to those of silicified woods recently found in the Carboniferous of Australia. Indeed, Crisafulli18 already mentioned the presence of silicified woods with affinities to the Dadoxylon-Araucarioxylon complex in the Yaguarí Formation, but following the opinion of Maheshwari54, she assigned them to Araucarioxylon roxoi (=Dadoxylon roxoi, cited for the Estrada Nova Formation of Brazil) with well marked growing rings55, probably suggesting that this taxon was widely extended in the region. Other specimens described to come from the upper member of the Yaguarí Formation were even assigned to Bageopitys, a genus previously cited for the underlying Melo Group56 and the Irati Formation of Brazil57. Intriguingly, this genus apparently shows poorly marked growing rings, a condition that can depend on environmental factors, and not represent an anatomical diagnostic character. The gymnosperm that we describe herein preserves a low amount of true and thin growing rings, and some false rings as well. The presence of the latter can be an environmental proxy that suggests occasionally dry and arid periods58. Other features, such as the nature of the rays (uniseriate-biseriate) could also be variable within a single individual, and its variability within a taxon is often measured in just a single specimen.

It is possible that the Dadoxylon-Araucarioxylon controversy can be marked for the great plasticity shown in general by plants as a response to changing environmental conditions. On this respect, it is worth to note that as early as 1902, Scott48 described the issue between these two taxa, and disregarding with almost all the succeeding authors, recommended to validate both of them, using Dadoxylon for Paleozoic records and Araucarioxylon for Mesozoic and Tertiary ones. Scott48 based such recommendation in the fact that Paleozoic wood would be more closely related to the Cordaitaleans, while araucarioid features would be more extended from the Mesozoic.

The presence of primitive, cordaitalean-like features, mainly convening to the primary xylem in woods preserving the “Dadoxylon” pattern, suggests a close relation of this ancient taxon to the recent genus Ginkgo, which could have also cordaitaleans affinities48.

As some previously described Permian wood fragments found in the Yaguarí Formation such as Baieroxylon cicatricum59 have been assigned to the Ginkgoales18)(56, it is possible that the herein described material (in a very preliminary form) can result interesting for future evolutionary studies on early gymnosperms.

3.4. A new tetrapod footprint ichnoassociation of possible Permian affinity

The first tetrapod footprints found from the Yaguarí Formation, and in particular from the middle-upper part of the Villa Viñoles Member (below the Buena Vista fossiliferous conglomerates), highlight the possible occurrence of three ichnogenera: cf. Capitosauroides isp., cf. Karoopes isp., and cf. Pachypes isp., which are attributed to therocephalians, gorgonopsids, and pareiasauromorphs, respectively. This would constitute the first South American record of these three ichnotaxa. Also, these footprints would be the first evidence of therapsids, and in particular therocephalians and gorgonopsids, from Uruguay. This tetrapod footprint ichnoassociation can potentially provide clues on the age of the Y-BV-S, and in particular of the upper Villa Viñoles Member (including the BVF). Capitosauroides ranges from the late Guadalupian to the Early Triassic, Karoopes from the late Guadalupian to the Lopingian, and Pachypes from the late Cisuralian to the Lopingian42)(46)(60. Therefore, this ichnoassociation is potentially indicative of a late Guadalupian-Lopingian age, in agreement with the known paleomagnetic data on the YF s. l. and the other relevant fossils of the Colonia Orozco Fauna. Unfortunately, the collected tetrapod footprint material is generally fragmentary and poorly-preserved, so these conclusions must be considered as provisional. Nevertheless, the potential of these localities for further prospection is noteworthy and highly recommended.

4. Conclusions

The prospection of deposits assigned to the middle-upper section of the Villa Viñoles Member (upper Yaguarí Formation s. l.) carried out in recent years has resulted in the finding of relevant fossil materials, which are the subject of the present work.

The fossils found (a permineralized silicified stem and several tetrapod footprints) are here preliminarily described and will be in deep studied in forthcoming papers.

However, the already performed analyzes on the permineralized stem suggest that it is a gymnosperm related to the Dadoxylon-Araucarioxylon complex, which has been already reported to the Yaguarí Formation and to other roughly regional contemporaneous deposits. Even though, given its particular microanatomy, it is very possible that it represents a new taxon.

Concerning the tetrapod footprints, even though they are generally represented by fragmentary and poorly-preserved specimens, they are the first and at the moment only evidence of the presence of tetrapods in the Yaguarí Formation s. l., preserved below the intraformational conglomerates of the top of the Villa Viñoles Member (sensu Elizalde et al., 1970) that have yielded the Colonia Orozco Fauna.

The described footprints suggest the presence of therapsids and particularly therocephalians and gorgonopsids, which were not yet reported for late Paleozoic deposits of South America. Moreover, therapsids are intriguingly absent in the overlying Colonia Orozco Fauna, which makes it interesting to investigate the evolutionary processes that led to these virtual disappearance perhaps related to the proposed Middle Permian mass extinction61. Other suggested ichnotaxon (Pachypes), associated to pareiasauromorphs, could be relevant because despite pareiasaurs are present in the Permian of Brazil, the ichnotaxon per se has never before been registered in South America.

Therefore, these provisional conclusions would enhance the interest for further future prospection of footprints in these localities for the discovering of new and more complete specimens.