Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.13 no.1 Montevideo 2024 Epub June 01, 2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v13i1.3640

Original Articles

Self-Help Strategies for Palliative Care Patients and their Families: An Integrative Review

1 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil, enf.rayssa.marques@gmail.com

2 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil

Objective:

To identify the strategies available in the international literature that provide self-help methods for palliative care patients and their family members

Method:

This is an integrative literature review conducted between April and May 2022 in the following online databases and libraries: Medline, Scielo, Scopus, CINAHL and Web of Science. The studies were selected rigorously using different combinations of MESH terms and keywords self-help, groups, palliative care, medicine in literature, literature, health, disease; with the AND Boolean operator. An online review management app was used, Rayyan - Intelligent Systematic Review, performing a double-blind check. A total of 3,250 studies were found in the primary search; after applying the exclusion criteria, 16 articles comprised the analysis corpus.

Keywords: palliative care; help strategies; self-help; grief; relatives

Objetivo:

Identificar as estratégias disponíveis na literatura internacional que forneça métodos de autoajuda para pacientes em cuidados paliativos e seus familiares.

Método:

Trata-se de uma revisão integrativa da literatura, realizada entre abril e maio de 2022, utilizando as bases de dados e bibliotecas online Medline, Scielo, Scopus, CINAHL e Web of Science. Os estudos foram selecionados de forma rigorosa, através da utilização de diferentes combinações dos MESH’s e palavras chaves self-help, groups, palliative care, medicine in literature, literature, health, disease com o operador booleano AND. Foi utilizado um aplicativo online de gerenciamento de revisões, Rayyan - Intelligent Systematic Review, sendo realizada a dupla verificação cega. Na busca primária foram encontrados 3259 estudos, após a aplicação dos critérios de exclusão 16 artigos compuseram o corpus de análise que usou como forma de apreciação a metodologia descritiva.

Resultados:

Obteve-se como principais achados a utilização de grupos de autoajuda como uma importante estratégia para auxiliar pacientes e familiares em situações desafiadoras que cernem o final de vida, outras estratégias foram vislumbradas como o uso de cartilhas, espaços e programas, que tendem a auxiliar nos momentos em que é necessário a comunicação de más notícias ou passar por situações de perda antecipatória e luto. Houve a predominância de estudos de abordagem qualitativa, e em maioria realizados na Suécia.

Conclusão:

Evidenciou-se que a estratégia dominante foi os grupos de autoajuda, que demonstraram ser um espaço de troca de conhecimento e experiências pessoais, entre os indivíduos participantes

Palavras-chave: cuidados paliativos; estratégias de ajuda; autoajuda; luto; familiares

Objetivo:

Identificar las estrategias disponibles en la literatura internacional que brindan métodos de autoayuda para pacientes de cuidados paliativos y sus familias.

Método:

Se trata de una revisión bibliográfica integrativa, realizada entre abril y mayo de 2022, utilizando las bases de datos y bibliotecas en línea Medline, Scielo, Scopus, CINAHL y Web of Science. Los estudios fueron seleccionados rigurosamente, utilizando diferentes combinaciones de MESH y las palabras clave autoayuda, grupos, cuidados paliativos, medicina en la literatura, literatura, salud, enfermedad, con el operador booleano AND. Se utilizó una aplicación en línea de gestión de revisiones. Rayyan - Intelligent Systematic Review, con verificación doble ciego. En la búsqueda primaria se encontraron 3259 estudios; tras aplicar los criterios de exclusión 16 artículos compusieron el corpus de análisis.

Resultados:

Los principales hallazgos fueron el uso de grupos de autoayuda como estrategia importante para asistir a pacientes y familiares en situaciones desafiantes al final de la vida. Se vislumbraron otras estrategias como el uso de cartillas, espacios y programas, que tienden a asistir en momentos en que es necesario comunicar malas noticias o atravesar situaciones de pérdida anticipada y duelo. Hubo un predominio de estudios con enfoque cualitativo, y la mayoría de ellos realizados en Suecia.

Conclusión:

Se evidenció que la estrategia dominante fueron los grupos de autoayuda, que demostraron ser un espacio para el intercambio de información conocimientos y experiencias personales entre las personas participantes.

Palabras clave: cuidados paliativos; estrategias de ayuda; autoayuda; duelo; miembros de la familia

Introduction

Regarding self-help, the first book drafts emerged in the mid-18th century, with self-help literature serving as a self-resolution tool for individuals of that time who sought self-improvement autonomously. 1

End-of-life and grief represent complex experiences that require understanding and the adoption of supportive strategies for patients and their families. The end-of-life is a disease stage in which the death possibility is real and life expectancy is six months. 2 In turn, grief is a natural and expected reaction to loss and to human development, as it is a part of human (non)existence. 3)

In this sense, individuals undergoing end-of-life situations and grief are eligible for a palliative care approach. Palliative care is an approach that involves promoting quality of life for patients with diseases that do not respond to curative treatments and for their family members. 4 Among the palliative care principles are support for patients to live as actively as possible until death and assistance for their families during illness and grief. 5 Such being the case, it is important for health professionals to develop strategies to ensure that these principles are implemented.

For example, one of the options is to incorporate booklets, videos, infographics and leaflets in pain assessment and control. Booklets are used as an important strategy to address doubts through clear and objective information, leading to an understanding of the health-disease process, clinical conditions and self-care practices. 6 Additionally, they can use videos, booklets, groups, phone calls, websites and consultation-based guidelines to carry out health education actions that can enhance communication about procedures, understanding and acceptance of palliative care, thereby qualifying them. 7 Furthermore, another strategy is to operationalize self-help services in institutions for care in the face of grief. 8

Regarding approaches to the patients and their family members, conducting self-help supporting groups seems to be relevant. However, at certain illness stages, it may be more challenging to organize such groups due to disease limitations or the psychological impact of facing the loss. Despite this, a study has shown that individuals with diseases no longer responsive to curative treatments or their bereaved family members use social media as a support and coping strategy, sharing experiences and stories about death, dying and grief. Thus, viewers who are moved by or identify with the posts come together, even if virtually, creating a large virtual self-help group, providing a sense of support and reducing feelings of loneliness. 9 Supporting this, a study 10 indicates that sharing details about one’s own disease is part of a person’s process of recognizing themselves as ill and relating to others, sharing stories and connecting realities.

In light of the above, this study aims at identifying self-help strategies for palliative care patients and their family members in the international literature, with the aim of assisting patients and/or family members in coping with the end-of-life process. Therefore, the research contributes to a larger investigation that aims at analyzing how self-help books assist individuals in facing the end of life in contemporary times.

Methodology

This is an integrative literature review that followed six stages: 11 1) Define and formulate the question that will be the review object; 2) Conduct the search and selection of studies; 3) Extract the data from the primary studies; 4) Critically assess the studies included in the review; 5) Synthesize the findings; and 6) Present the results.

In the first stage, the research question was defined as follows: Which self-help strategies (groups, books, videos, films) are found in the national and international literature for palliative care patients and their family members? The research question was based on the PICO strategy, with: P - Participants: patients and family members, I - Intervention: self-help strategies, C - Comparison: not applicable, and O - Outcomes: effects of the strategies for patients and family members.

In the second stage, studies were identified between April and May 2022 using indexed descriptors such as Medical Subject Headings (MESH) in electronic databases, including the Medical Literature and Retrieval System Online (Medline) via PubMed, Scientific Electronic Library Online (Scielo), SciVerse Scopus owned by Elsevier, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) from EBSCO and, finally, Web of Science from Clarivate Analytics. Access to and retrieval of the documents from restricted-access databases were through the Journals Portal of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Ensino Superior, CAPES), via the Federated Academic Community (Comunidade Acadêmica Federada, CAFe).

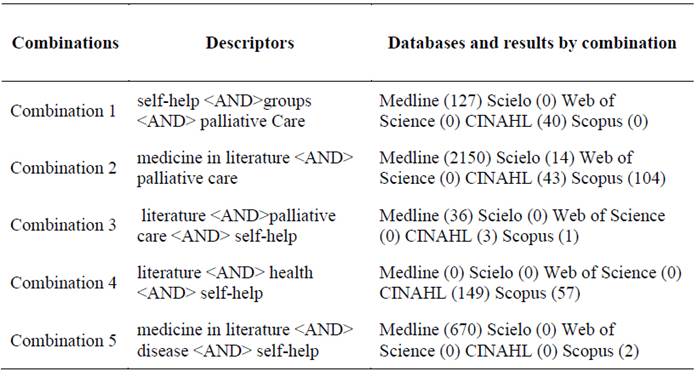

The inclusion criteria were as follows: original articles involving palliative care adults and/or bereaved family members, published with open access in English, Portuguese, Spanish and French. In turn, the exclusion criteria corresponded to reflection articles, children in end-of-life care, and closed access. In order to obtain more studies, no time delimitation was established. After associating the descriptors, 3,259 documents were identified through the use of different combinations of MESH terms, as presented in Table 1.

After due identification, the files were downloaded and added to the Rayyan - Intelligent Systematic Review free online app for reading titles and abstracts. The reading was conducted using the double-blind verification method. Subsequently, working in pairs, both authors of this manuscript discussed any discrepancies to finalize the number of findings.

Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 36 articles were identified for full-text reading, of which 16 comprised the corpus for the review analysis. The data were then entered into the PRISMA program to generate the flowchart of the database. Figure 1 represents the diagram corresponding to the search and selection of articles.

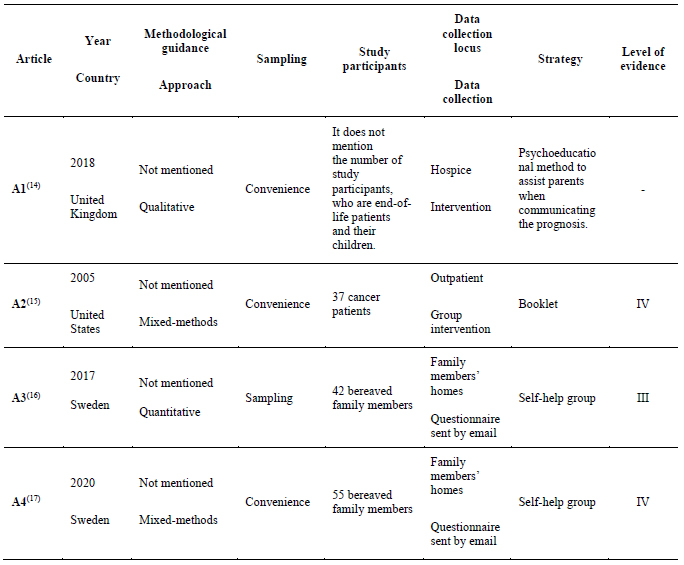

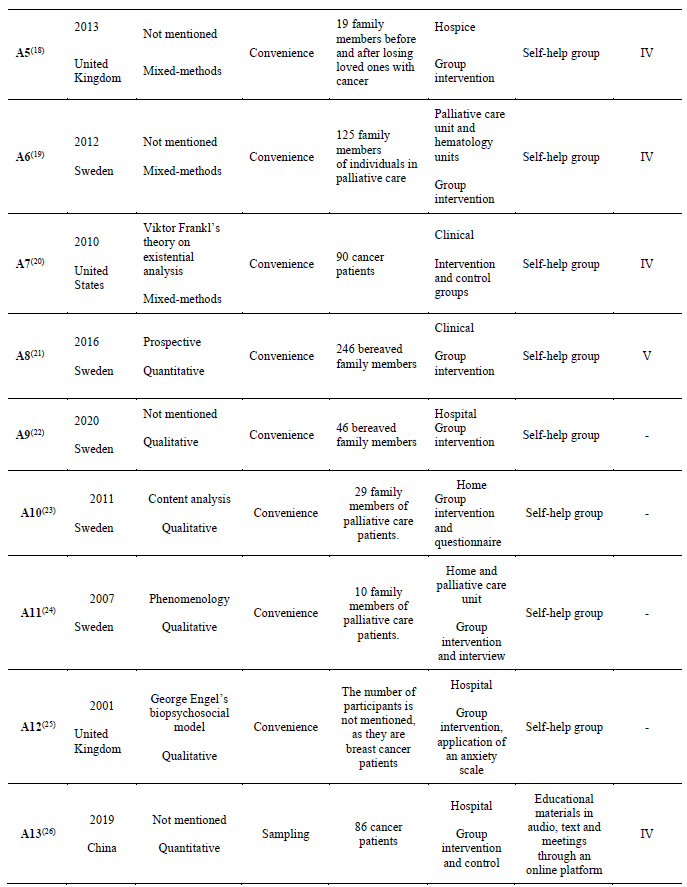

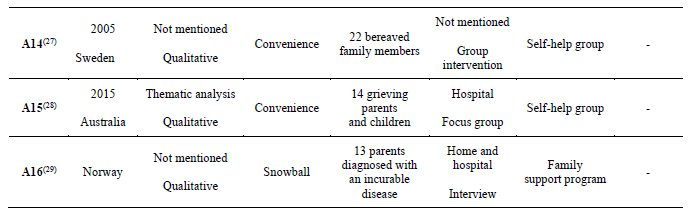

In the third stage, the data were extracted into a form built in the Google research management app, divided into sections. The first section included the following: title, author, year, country, participants, study approach, and level of evidence concerning the methodological design. The second section comprised methodological design and theory, sampling, selection of the participants, approach method, number and participants’ refusal. Finally, the third section contained data related to the article’s results, such as the central topic, main results and limitations. Subsequently, in the third and fourth stages, the quality of the quantitative studies was assessed by the level of evidence 12 and that of the qualitative studies through a checklist adapted from the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guide. 13 In the fifth stage, the data were analyzed descriptively and the results were organized through a synthesis of the strategies, using thematic similarity as the main factor for creating the analysis categories. The sixth stage, Presentation of the results, is described below. Table 2 T2a T2b presents the characterization of the 16 articles that comprised the empirical material of the review.

Results

Based on Table 2, there is predominance of studies conducted in Sweden, especially with a qualitative approach. Furthermore, the self-help group strategy was the main focus highlighted in this review, dividing it into groups for patients and groups for family members.

Self-help support groups for people in Palliative Care

The materials found on self-help groups for patients in palliative care will be presented in this category. The countries where the studies were conducted were the United States of America, 20 United Kingdom 25 and China. 26 All had their data collection carried out in intervention groups, 19,24,25 and the strategies used were self-help support groups 20,25 and educational materials in audio, text and online meetings. All studies were positive in relation to their objectives proposed.

In the United States, the study main objective was to create and evaluate a group to help patients with advanced cancer sustain or increase their sense of meaning, peace and purpose in life, even as they approached the end of life. Two groups were analyzed: one that performed interventions to assist in psychospiritual well-being and a sense of meaning, and another group was just a support group. In addition to improving spiritual well-being and an enhanced sense of meaning, the first group appeared to present a reduction in psychological distress. Modest improvements were identified in hopelessness, desire for death and anxiety, and these treatment effects increased over the two-month follow-up period when compared to the support group. 20

In the United Kingdom, meetings of a psychoeducational group for young women with cancer were evaluated. The need for the group arose from the observation that these women needed better life quality for the time they still had to live. The group meetings were varied and took on aspects such as dinners, seminars and cognitive therapies. The female participants were all under 55 years old and all underwent an initial assessment, with depression levels observed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) after they were introduced to the group. The environment was designed in a private but informal room, providing a favorable space for meetings -spacious, well-ventilated rooms with lounge chairs, and provision of drinks to break the hostile atmosphere. The assessments of the group’s functioning were conducted informally through questionnaires, but the data found in the questionnaires suggest an improvement in the anxiety and depression levels, aiding in the reduction of these symptoms in breast cancer patients, whether with a curative outcome or with palliative care. 25

Another quantitative research study evaluated two groups: 42 participants in a control group and 44 in the experimental group. The patients in the experimental group were trained to use a platform called WEB LRP within a WeChat app, which provided video calls to reassess life. Through the creation of a family tree and reliving feelings throughout life, the platform offered asynchronous audio and text materials 24 hours a day, along with weekly meetings for six weeks. The life review meetings lasted between 40 and 60 minutes and, when a patient experienced negative emotions, they could be accompanied by psychologists. After this process, a questionnaire was administered to assess different domains. Although the study caused a painful process by making people relive certain feelings and moments in their life, it was possible to evaluate that the “space and mind” module allowed the patients to express their feelings more clearly through words. The “memory prompts” module allowed reliving family-related feelings, arousing positive emotions. However, it was not possible to assess whether there were significant differences in sense of life and hope between both groups. 26

Self-help support groups with family members of individuals in Palliative Care or with bereaved people

Materials were found addressing self-help groups for families of individuals in palliative care or experiencing the grieving phase. Six were conducted in Sweden,(17, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27) one in the United States, 15 one in Australia 28 and another one in the United Kingdom. 18 Five had their data collection conducted solely in group interventions, (15, 18, 21, 22, 27) one only through an online questionnaire, 17 the others resorted to group intervention and a questionnaire 23 or to interviews, 24 and one with a focus group.28

Participation in support groups was assessed as very beneficial by 22 out of the 40 participants. The following were among the benefits highlighted from participating in support groups: the opportunity to talk about one’s own feelings without burdening those close; discovering that one is not alone in parental grief; and experiencing companionship with other young people in similar circumstances. 15

A support group for bereaved family members had the primary objective of providing a space for sharing grief experiences, receiving support and supporting those in similar situations. Seven biweekly meetings were held, and the activity was coordinated by professionals such as nurses, social workers, chaplains and deacons. The topics covered in the meetings included the following: who had died and how; changes in the family, for example: grief feelings and experiences and existential thoughts; what they found as support; memories and ongoing bonds; and moving forward. There was little difference in the well-being-related data between the first and last meeting. The low psychosocial well-being and little improvement during the study period indicate the potential need for bereavement support, not only temporarily. 17

Another group strategy with family members separated them into two groups, recognizing that people are in different moments and processes: one group consisted of individuals experiencing the phase before death, and the other group was for support to the bereaved. Thus, the family members started in the pre-death group and. after their family member’s death, they began participating in the support group for the bereaved. The patients were not allowed to participate in the meetings. The meetings were further subcategorized by age, and the families involved indicated that attending the group helped them accept and communicate their feelings more effectively, as well as get to know other families in the same situation, providing comfort and support. In the age group of 10 to 16 years old it was identified that, with the limited time of 90 minutes, they did not feel comfortable expressing themselves. Therefore, game nights were organized, with activities such as pizza and bowling, in order to try to bring them closer and assist them. 18

The support group program addressed different types of family members’ needs, as mentioned in the previous study and this earlier research, with another two studies emerging from the database. The participants felt that the topics presented in the support group reflected their everyday life and focused on significant situations for their lives with seriously-ill people. They mentioned that the program structure with weekly meetings, free time for group conversations and contributions from health care professionals offered an opportunity to establish relationships. An important aspect about the support group program was that the group leaders and invited professionals were members of the team caring for the sick person. The participants could get to know members from all professions, which was seen as advantageous. They felt invited and encouraged to contact them; some participants reached out to various team members for consultation and help after the meetings. This gave them confidence that the sick person was receiving good nursing care in their daily lives. 23,24

Some participants found the program stressful and felt insecure the first time they met in a group. These feelings were tempered by the welcoming atmosphere in the meetings from the beginning. The group leaders were seen as companions who shared feelings and thoughts, provided advice and support while guiding the group in relaxed conversations. Within the group, they felt comfortable crying and talking about how tired they were; the support group became a place where they could let go of what they hid from themselves, the sick person and other family members or supporting network. Moreover, in the group, they talked about anger and annoyance with the sick person and with the disease itself. 23,24

The support group program mentioned in the three previous studies generated additional results shown in this research. Data from a larger study are presented, which was subdivided into family members of end-of-life patients monitored in specialized palliative care services and in a hematology unit; the group meetings took place between January and December 2009. The family members that participated in the support group program significantly increased their perceptions about preparedness, competence and reward in caregiving. The intervention seemed to impact the participants’ perceptions regarding caregiving performance, and they felt more prepared and competent in their role. There were no significant changes in hope, anxiety, depression symptoms or health.

A study conducted with bereaved family members in Sweden adopted participation in a support group, without specifying the approaches developed. It showed that grief is quite severe for people who lose very close relatives but tends to decrease and even cease within a year after the loss. Participation in the group did not result in improvements in grief, anxiety or depression during a year of intervention and. after this period, 49 % of the participants indicated that they did not find participation necessary and that they managed to cope with grief on their own. 21

Another study identified some factors that could not be addressed in the previously mentioned study on the support group for family members and showed positive impacts for the participants in the groups, such as on self-image. For example, some participants mentioned feeling visibility and self-determination and the need to reclaim their role as protagonists, as well as social relationships, living and talking with other people. The study could not determine the long-term beneficial effects of the groups because it is an ongoing randomized study. However, in the short term, positive aspects identified by the participants can be evaluated. 22

In Sweden, a group gathered the participants to express their feelings, reliving the moment when the family member received the disease diagnosis. All meetings started with an open circle, providing ample space for dialogue and, over time, the facilitators began to identify certain taboo topics such as caregiving, which oftentimes became a point of discussion between the family member, the dying person and other relatives. The concept of transition emerged in the conversations, with family members transitioning from assuming a role to becoming a caregiver. The absence of the deceased person left them without a sense of purpose in life. The family members felt that the space was necessary for identifying new ways to support themselves and recover. However, conclusion of the group made it challenging to provide longer-term follow-up for these people. 27

Another approach found was a support group that met at the same location where the loved one passed away. Three topics were identified: the personal grief experience; revisiting the hospital; and experiences of caring for grief. The participants discussed the personal nature and challenges of grief, their experiences and needs. Regarding revisiting the hospital after the death of a loved one, for some participants the hospital held significant meaning for the family, and returning to it was a source of comfort. For others, it was very difficult to go back to the hospital for any reason after the death of a loved one. The participants reported that the most important elements of the care provided were practical information, the opportunity to stay overnight with their loved ones, and overall support from the staff. Although the hospital had this characteristic, the support for the bereaved individuals was not religious, and the service was provided by the Pastoral Care department. The support groups for grieving individuals provided an opportunity for interaction with others experiencing grief and loss, especially if the focus group was held in the hospital, where some participants found comfort due to familiarity with the location and health professionals.28

Other self-help strategies: spaces, booklets and programs

Other self-help strategies also emerged in the materials found, offering alternatives both for patients and for family members with the objective of improving coping with end-of-life situations.

In a support service within a Hospice, they aided parents with a serious disease in communicating with their children about end-of-life and loss, assisting the children in the grieving process. This involved using psychoeducational methodologies. The hospice team created a space called Cantinho do Silêncio (Quiet Little Place), which had a structure prepared to deal with children and young people. The environment included non-fiction books that encouraged them to talk about their feelings, as well as assisting adults in using appropriate language to understand and address moments marked by emotional intensity. 16

In another study, the patients received quarterly mailings containing material resembling a self-help booklet with strategies aimed at understanding and reducing anxiety and depression, improving spirituality, and accepting death. The study involved two groups: the intervention group and the control group, with 37 participants receiving the intervention. Regarding anxiety, depression and spirituality, there was no significant improvement after the interventions. However, there was a small improvement in death acceptance when compared to the control group. 14

For parents diagnosed with cancer without a response to modifying treatments, they described how the Family Support Program assisted and supported them in talking to their children about the diagnosis. In the program, they gained better understanding about their children’s thoughts and reactions and how the situation affected their everyday lives. The parents were grateful when the project workers asked the ‘difficult questions’, believing that this was important for family unity, serving as mediators. They reported that conflicts were reduced, allowing for more open discussion about the family situation and how to support their children’s coping, as well as planning for the future. The parents valued and appreciated this service, reporting many benefits related to family functioning, communication and openness. 29

Discussion

Certain characteristics, such as accepting death as part of the natural process, are discussed in post-modern societies. Different societies are moving towards identifying factors that can aid in improving the dying process.

Sweden emerged as the predominant country in the studies identified in this research, and some factors can justify this finding. The country has been discussing political narratives of Palliative Care since the 1970s and has established proposals in recent years focusing on the universalization of this type of care. 30

Considering that Sweden has a public health system, recent discussions have revolved around quality indicators. A study 31 published in 2015 and assessing the quality of death in 80 countries ranked Sweden sixteenth. The assessment was aimed at evaluating countries regarding the availability of palliative care, health environments, human and professional resources, care quality and community participation. 30 However, some narratives focus on issues such as medicalization, routinization and bureaucratization, which oppose the palliative care philosophy. It is possible to assess that these narratives are not linear and change according to the needs found by the populations.

Through 13 indicators, research study that evaluated end-of-life care in 81 countries sought to understand some aspects, including how the team helps patients deal with emotional issues, how professionals assist individuals in maintaining contact with friends and family members, and whether health professionals help patients deal with non-medical concerns. The assessment evaluated qualitative and quantitative aspects and managed to make a ranking based on the classification of indicators and economic aspects. Sweden ranks 17th, receiving a B grade, whereas Brazil occupies the 79th position and received an F grade. The study assessed the high correlation between income and the performance of each country’s health systems. An important aspect addressed in the study is the need to evaluate and classify the experiences of patients and caregivers using services, as the efforts should be directed towards improving services for this target population. 32

The most frequently identified self-help strategy was support groups, both for patients and for family members. Diverse evidence found in a research study conducted with women affected by breast cancer who participated in a support group showed that participation was beneficial. It helped them share experiences with others facing the same situation, thus understanding, supporting and encouraging coping with the disease, improving self-esteem and providing social support. 33

Through leaders of self-help groups for cancer patients, a survey conducted in Germany evaluated the points they consider favorable or not in the implementation of such services. It was possible to identify that the availability of service professionals, as well as the interest in maintaining an updated multidisciplinary team attentive to the demands, was pointed out as an essential factor for the implementation. On the other hand, lack of availability for physical structure and human resources, lack of knowledge and underestimation of the self-help effectiveness were identified as negative and important factors for the failure of the groups. 34

Another study conducted support groups for people in the grieving process, holding meetings with a mean duration of 45 minutes aimed at promoting demystification of taboos, prejudices and stereotypes, as well as relaxation activities to reduce anxiety and tension. It was identified that there were many complaints about the theme during the initial meetings; the participants found it unnecessary to talk about death. However, as the meetings progressed, the exchange of experiences became intense and they began to understand the need to make the topic a regular part of their discussions. 35

Another study aimed at providing theoretical support to encourage the use of reflection groups for those in mourning. The research identified that using conditioned questions reproduced from one participant to another proves beneficial as a trigger for discussions, along with the practice of mutual aid that expresses learning through sharing and exchanging social experiences. 36

When a potentially incurable disease is discovered, determinants are established both for the affected individuals and for those around them. A research study conducted to demonstrate support for the family that is with a patient in palliative care expresses that some aspects should be analyzed and worked on during the illness process, namely: integrating the family into the care process; mediating conflicts among family members; supporting and encouraging different forms of communication for those who have difficulty expressing their feelings; and preventing situations of social isolation and loneliness; as well as identifying risk situations for complicated grief. 37

Another survey investigates the types of mourning experienced by relatives of people with a disease without any possibility of curative therapy. The type that showed the greatest need for further exploration was anticipatory grief, which occurs from the moment of diagnosis. The study showed that some participants were affected by a late diagnosis when the disease was already in an advanced stage, causing grief to set in immediately. To address this, health teams that monitor these family members should work to make the process less painful. 38

Over the past three years, the world has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has required the use of different resources to maintain continuity of various services, leading to the widespread use of technologies. As a result, a study conducted with people who lost a family member due to COVID-19 and participated in an online support group highlighted that, due to the increase in socially vulnerable individuals with low financial resources, the opportunity for free and online psychological support was extremely relevant. The group was shown to provide an environment for mutual exchange, redefinition of loss, and social and emotional support. 39

The study also revealed that communicating bad news, especially related to the end of life, can be a challenge, considering that the younger the target audience, the more challenging it becomes. According to the study, 39 the parents’ perception tends to underestimate the children’s cognitive and emotional capacity to deal with certain situations, leading to the concealment of truths and hindering open conversations about the death of a parent. 40 Another study examining how to communicate the death of a family member to children identified that some elements are used to tailor information according to the children’s age group. These include metaphors, helping the child maintain the image of the deceased through narratives, photographs or videos, or involving the child in rituals. 41

The use of booklets has become an important method for disseminating different contents in a more accessible way that can be consumed by various people at any moment. A study focused on developing and sharing booklets to spread knowledge about anxiety disorders among adolescents in schools found that this type of material can assist in the social role and quality of information, encouraging people who identify certain symptoms to seek specialized help. 42

Another relevant study involves creating and disseminating educational materials for family caregivers of individuals in palliative care. This booklet allowed them to refer to the content whenever they had doubts about care, service hours and the differences between certain treatments. It promoted positive changes in supporting the adaptation process to the incurable condition of the family member. 43

Regarding the environment, informality showed a positive aspect in a study. 44 The research conducted with patients, family members and professionals sought to evaluate the relationship that the environment fosters in these interactions from different perspectives. It revealed that a space outside the clinical setting provides freedom to discuss various themes, fostering a genuine connection with people and improving aspects such as exchange of experiences, knowledge, confidence and meaning.

The current research presented limitations such as language restrictions and access to articles with open availability or via specific platforms, resulting in a low number of studies. The fact that no Brazilian studies were found shows the need to delve into the subject matter in the country, both in terms of research approaches and in the development of group strategies to enhance the experiences of palliative care patients and their family members.

Conclusions

This article allowed identifying self-help strategies for palliative care patients and their family members in the international literature, as the results show that no national studies meeting the research criteria were identified. Qualitative research approaches predominated among the studies, with Sweden standing out the most in productions on the theme.

As identified, some factors influence Sweden’s prominent position. The inclusion of public policies for the expansion of this type of care implies ensuring access and financial, material and human resources. In contrast to this, we can assess that the lack of national studies on the topic can be related to the absence of public policies focused on palliative care.

Self-help groups foster an exchange of experiences among individuals undergoing similar situations. Just as this final process is permeated with fears, insecurities and difficulties, services that offer support in communicating bad news are favorable, understanding that each target audience and age group requires a unique approach. It is emphasized that participation in groups did not show improvement evidence in terms of the meaning of life or hope, nor in relation to reducing stress, depression and anxiety.

The research findings allow for an assessment of the gaps identified and the expansion of studies to deepen strategies that were not identified in the survey, providing support sources for individuals in the final life stages and/or to bereaved family members.

REFERENCES

1. Rudiger F. Literatura de auto-ajuda e individualismo: contribuição do estudo de uma categoria da cultura de massa contemporânea. São Paulo: Editora Da Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul; 1996. [ Links ]

2. Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaniya N, Dev R, De La Cruz M, Kim SH, et al. Concepts and definitions for “actively dying,” “end of life,” “terminally ill,” “terminal care,” and “transition of care”: a systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (Internet). 2014 (citado 2023 jul 14);47(1):77-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.021 [ Links ]

3. Cavalcanti AKS, Samczuk ML, Bonfim TE. O conceito psicanalítico do luto: uma perspectiva a partir de Freud e Klein. Psicol inf (Internet). 2013 (citado 2023 jul 05);17(17):87-105. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1415-88092013000200007&lng=pt&nrm=iso [ Links ]

4. World Health Organization. Palliative Care (Internet). Geneva: WHO; 2020 (citado 2023 jul 12). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care [ Links ]

5. International Association for Hospice & Palliative Care . Palliative Care Definition (Internet). Houston: IAHPC; 2019 (citado 2023 jul 12). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care/definition/ [ Links ]

6. Costa, GL, Andrade, ES, Guilherme, FJA, Ferreira, RKR. A criação de uma cartilha educativa para estimular a adesão ao tratamento do portador de diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Revista Rede de Cuidados em Saúde (Internet). 2014 (citado 2023 jul 05);8(2):01-04. [ Links ]

7. Cordeiro, FR, Marques R dos, S, Silva K de, O, Martins, MC, Zillmer, JGV, Sant'AnaTristão, F. Educação em saúde e final de vida no hospital. Av Enferm (Internet). 2022 (citado 2023 jul 12);40(1):113-133. doi: 10.15446/av.enferm.v40n1.86942 [ Links ]

8. Aciole GG, Bergamo DC. Cuidado à família enlutada: uma ação pública necessária. Saúde em Debate (Internet). 2019 (citado 2023 jul 05);43(122):805-818. doi: 10.1590/0103-1104201912212 [ Links ]

9. Cordeiro FR, Blumentritt JB, Silveira JM, Mourão DP, Corrêa IM, Silva NK da. A morte é “pop”: análise de perfis sobre fim de vida e cuidados paliativos no Instagram. Revista M (Internet). 2023 (citado 2023 jul 14);8(16):e11469. doi: 10.9789/2525-3050.2023.v8n16.e11469 [ Links ]

10. Bozz A, Gomes SH. Conectar e compartilhar: a biossociabilidade de pacientes com câncer. Interface (Botucatu) (Internet). 2023 (citado 2023 jul 14);27:e220008. doi: 10.1590/interface.220008 [ Links ]

11. Mendes KDS, Silveira RCCP, Galvão CM. Use of the bibliographic reference manager in the selection of primary studies in integrative reviews. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem (Internet). 2019 (citado 2023 jul 12);28:e20170204. doi: 10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2017-0204 [ Links ]

12. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Gallagher-Ford L, Stillwell SB. Sustaining Evidence-Based Practice Through Organizational Policies and an Innovative Model: The team adopts the Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration model. American Journal of Nursing (Internet). 2011 (citado 2023 jul 16);111(09):57-60. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000405063.97774.0e. [ Links ]

13. Souza VR dos S, Marziale MHP, Silva GTR, Nascimento PL. Tradução e validação para a língua portuguesa e avaliação do guia COREQ. Acta paul enferm (Internet). 2021 (citado 2023 jul 12);34:eAPE02631. doi: 10.37689/acta-ape/2021AO02631 [ Links ]

14. Macpherson C. Supporting parents and children prior to parental death in an NHS setting. Taylor & Francis online (Internet). 2018 (citado 2023 jul 12);37(2):67-73. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2018.1493639 [ Links ]

15. Miller DK, Chibnall JT, Videen SD, Duckro PN. Supportive-affective group experience for persons with life-threatening illness: reducing spiritual, psychological, and death-related distress in dying patients. J Palliat Med (Internet). 2005 (citado 2023 jul 12);8(2):333-43. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.333 [ Links ]

16. Olsson M, Lundberg T, Fürst CJ, Öhlén J, Forinder U. Psychosocial Well-Being of Young People Who Participated in a Support Group Following the Loss of a Parent to Cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care (Internet). 2017 (citado 2023 jul 12);13(1):44-60. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2016.1261755 [ Links ]

17. Lundberg T, Forinder U, Olsson M, Fürst CJ, Årestedt K, Alvariza A. Poor Psychosocial Well-Being in the First Year-and-a-Half After Losing a Parent to Cancer - A Longitudinal Study Among Young Adults Participating in Support Groups. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care (Internet). 2020 (citado 2023 jul 12);16(4):330-345. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2020.1826386 [ Links ]

18. Popplestone-Helm SV, Helm DP. Setting up a support group for children and their well carers who have a significant adult with a life-threatening illness. Int J Palliat Nurs (Internet). 2009 (citado 2023 jul 12);15(5):214-21. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.5.42346 [ Links ]

19. Henriksson A, Årestedt K, Benzein E, Ternestedt B-M, Andershed B. Effects of a support group programme for patients with life-threatening illness during ongoing palliative care. Palliat Med (Internet). 2013 (citado 2023 jul 12);27(3):257-64. doi: 10.1177/0269216312446103 [ Links ]

20. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, Pessin H, Poppito S, Nelson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology (Internet). 2010 (citado 2023 jul 12);19(1):21-8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556 [ Links ]

21. Näppä U, Lundgren A-B, Axelsson B. The effect of bereavement groups on grief, anxiety, and depression - a controlled, prospective intervention study. BMC Palliat Care (Internet). 2016 (citado 2023 jul 12);15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0129-0 [ Links ]

22. Näppä U, Björkman-Randström K. Experiences of participation in bereavement groups from significant others’ perspectives; a qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care (Internet). 2020 (citado 2023 jul 12);19:124. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00632-y [ Links ]

23. Henriksson A, Benzein E, Ternestedt B-M, Andershed B. Meeting needs of family members of persons with life-threatening illness: a support group program during ongoing palliative care. Palliat Support Care (Internet). 2011 (citado 2023 jul 12);9(3):263-71. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000216 [ Links ]

24. Henriksson A, Andershed B. A support group programme for relatives during the late palliative phase. Int J Palliat Nurs (Internet). 2007 (citado 2023 jul 12);13(4):175-83. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.4.23484 [ Links ]

25. Smeardon K. Fighting Spirit: a psychoeducational group for younger women with breast cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs (Internet). 2001 (citado 2023 jul 12);7(3):120-8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.3.8910 [ Links ]

26. Zhang X, Xiao H, Chen Y. Evaluation of a WeChat-based life review programme for cancer patients: A quasi-experimental study. J Adv Nurs (Internet). 2019 (citado 2023 jul 12);75(7):1563-1574. doi: 10.1111/jan.14018 [ Links ]

27. Milberg A, Rydstrand K, Helander L, Friedrichsen M. Participants’ experiences of a support group intervention for family members during ongoing palliative home care. J Palliat Care (Internet). 2005 (citado 2023 jul 12);21(4):277-84. PMID: 16483097 Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16483097/ [ Links ]

28. Brown J, Gardner J. Qualitative evaluation of a hospital bereavement service: the perspective of grieving adults. Taylor & Francis online (Internet). 2015 (citado 2023 jul 12);34(2):69-75. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2015.1064582 [ Links ]

29. Bugge KE, Helseth S, Darbyshire P. Parents' experiences of a Family Support Program when a parent has incurable cancer. J Clin Nurs (Internet). 2009 (citado 2023 jul 12);18(24):3480-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02871.x. [ Links ]

30. Ågren A, Krevers B, Cedersund E, Nedlund A-C. Policy Narratives on Palliative Care in Sweden 1974-2018. Health Care Analysis (Internet). 2023 (citado 2023 jul 16);31:99-113. doi: 10.1007/s10728-022-00449-1 [ Links ]

31. The Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking palliative care across the world. Lien foundation: The Economist Intelligence Unit; 2015 (citado 2023 jul 2016). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.lienfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2015%20Quality%20of%20Death%20Report.pdf [ Links ]

32. Finkelstein EA, Bhadelia A, Goh C, Baid D, Singh R, Bhatnagar S, et al. Cross Country Comparison of Expert Assessments of the Quality of Death and Dying 2021. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (Internet). 2022 (citado 2023 ago 01);63(4):e419-e429. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.015 [ Links ]

33. Martins ARB, Ouro TA do, Neri M. Compartilhando vivências: contribuição de um grupo de Apoio para mulheres com câncer de mama. Rev. SBPH (Internet). 2015 (citado 2023 jul 12);18(1):131-151. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-08582015000100007&lng=pt. [ Links ]

34. Ziegler E, Nickel S, Trojan A, Klein J, Kofahl C. Self-help friendliness in cancer care: A cross-sectional study among self-help group leaders in Germany. Wiley Online Library (Internet). 2022 (citado 2023 jul 16);25:3005-3016. doi: 10.1111/hex.13608 [ Links ]

35. Luz LP da. O Grupo de apoio como estratégia metodológica para trabalhar o luto. Revista de Iniciação Científica (Internet). 2007 (citado 2023 jul 12):5(1). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.periodicos.unesc.net/ojs/index.php/iniciacaocientifica/article/view/171 [ Links ]

36. Luna IJ. Uma proposta teórico-metodológica para subsidiar a facilitação de grupos reflexivos e de apoio ao luto. Nova Perspectiva Sistêmica (Internet). 2020 (citado 2023 jul 12);29(68):46-60. doi: 10.38034/nps.v29i68.585 [ Links ]

37. Reigada C, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Novellas A, Pereira JL. O Suporte à Família em Cuidados Paliativos/Family Support inPalliative Care. Textos & Contextos (Porto Alegre) (Internet). 2014 (citado 2023 jul 12);13(1):159-169. doi: 10.15448/1677-9509.2014.1.16478 [ Links ]

38. Magalhães SB de, Daltro MR, Reis TS dos. Recognized death: anticipatory grief experience of relatives of patients at the end of life (Internet). SciELO Preprints (Internet). 2023 (citado 2023 jun 05). doi: 10.1590/SciELOPreprints.5548 [ Links ]

39. Reis LB, Gonçalves ALM, da Silva M, Fiorese AR de M, Lambert CB, Silva KC da, et al. Acolhe(dor): Relato de Experiência de Grupo de Apoio On-line a Enlutados pela Covid-19. GUARA (Internet). 2023 (citado 2023 jun 05);1(15). doi: 10.30712/guara.v1i15.38424 [ Links ]

40. Emer M, Moreira MC, Haas SA. A criança e a iminência de morte do progenitor: o desafio dos pais na comunicação das más notícias. Rev. SBPH (Internet). 2016 (citado 2023 jul 12);19(1). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/rsbph/v19n1/v19n1a03.pdf [ Links ]

41. Lima VR de, Kovács MJ. Morte na família: um estudo exploratório acerca da comunicação à criança. Psicol cienc prof (Internet). 2011(citado 2023 jul 12);31(2):390-405. doi: 10.1590/S1414-98932011000200014 [ Links ]

42. Noronha EC, Gomes AMP, De Lima Yamaguchi KK. Cartilha sobre o distúrbio de ansiedade e a dificuldade no aprendizado. Scientia Naturalis (Internet). 2022 (citado 2023 jul 16);4(2). doi: 10.29327/269504.4.2-18 [ Links ]

43. Varela AIS, Rosa LM da, Radünz V, Salum NC, Souza AIJ de. Cartilha educativa para pacientes em cuidados paliativos e seus familiares: estratégias de construção. Rev enferm UFPE (Internet). 2017 (citado 2023 jul 16);11(Supl.7):2955-62. doi: 10.5205/reuol.11007-98133-3-SM.1107sup201717 [ Links ]

44. Grant MP, Philip JAM, Deliens L, Komesaroff PA. ‘It’s communication between people who are going through the same thing’: experiences of informal interactions in hospital cancer treatment settings. Supportive Care in Cancer (Internet). 2023 (citado 2023 jul 16);31(440). doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07900-6 [ Links ]

How to cite: Marques R dos S, Blumentritt JB, Cordeiro FR. Self-Help Strategies for Palliative Care Patients and their Families: An Integrative Review. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2024;13(1):e3640. doi: 10.22235/ech.v13i1.3640

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. R. D. S. M. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14; J. B. B. in 2, 3, 5, 13; F. R. C. in 1, 6, 10, 11, 14.

Received: August 17, 2023; Accepted: January 19, 2024

text in

text in