Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.13 no.1 Montevideo 2024 Epub 01-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v13i1.3400

Original Articles

Barriers and Facilitators of Health Care in People with Cancer in a Commune in Northern Chile: Qualitative Report

1 Universidad de Atacama, Chile

2 Universidad de Atacama, Chile, maggie.campillay@uda.cl

3 Universidad de Atacama, Chile

Introduction:

Cancer patients constitute a vulnerable group of the population due to the fragility caused by the disease. After consulting the literature, problems in access to health care are described

Objective:

Analyze the access barriers and facilitators that affect people with cancer in a commune in northern Chile

Methodology:

It was approached from the interpretive paradigm, qualitative methodology, and content analysis approach according to Bardin. The sample was intentional and considered four patients with cancer and four family caregivers. In-depth interviews were conducted, and a grid of guiding questions was used. Authorization was obtained from an accredited research ethics committee

Results:

There were identified a) availability, b) accessibility, c) psychosocial and d) bureaucratic barriers, and facilitators in e) support networks and f) prevention strategies

Conclusions:

Availability barriers are especially important for patients since they are associated with a deficit in the supply of timely oncological services. Networks of self-help groups stand out as facilitators of the therapeutic process. The identification of barriers and facilitators contributes to improving action strategies for better care of cancer patients

Keywords: barriers to access of health services; health equity; cancer care facilities

Introducción:

Los pacientes oncológicos constituyen un grupo vulnerable de la población por la fragilidad que les provoca la enfermedad. Consultada la literatura se describen problemas en el acceso a la atención en salud

Objetivo:

Analizar las barreras y facilitadores de acceso que afectan a personas con cáncer en una comunidad del norte de Chile

Metodología:

Se abordó desde el paradigma interpretativo, metodología cualitativa y enfoque análisis de contenido según Bardin. La muestra fue intencionada y consideró cuatro pacientes con cáncer y cuatro familiares cuidadores. Se realizaron entrevistas en profundidad y se utilizó una parrilla de preguntas orientadoras. Se contó con autorización de un comité de ética de investigación acreditado

Resultados:

Se identificaron barreras de a) disponibilidad, b) accesibilidad, c) psicosociales y d) burocráticas, y facilitadores en e) redes de apoyo y f) estrategias de prevención

Conclusiones:

Las barreras de disponibilidad son especialmente importantes para los pacientes, ya que se asocian a un déficit de oferta de servicios oncológicos oportunos. Destacan las redes de grupos de autoayuda como facilitador del proceso terapéutico. La identificación de barreras y facilitadores contribuye a mejorar las estrategias de acción, para una mejor atención de pacientes oncológicos

Palabras clave: barreras de acceso a los servicios de salud; equidad en salud; instituciones oncológicas

Introdução:

Os pacientes oncológicos constituem um grupo vulnerável da população devido à fragilidade causada pela doença. Após consulta à literatura, são descritos problemas no acesso aos cuidados de saúde

Objetivo:

Analisar as barreiras e os facilitadores de acesso que afetam as pessoas com câncer em uma comuna no norte do Chile

Metodologia:

Foi abordado a partir do paradigma interpretativo, metodologia qualitativa enfocada em análise de conteúdo segundo Bardin. A amostra foi intencional e considerou quatro pacientes com câncer e quatro cuidadores familiares. Foram realizadas entrevistas em profundidade e utilizada uma grade de perguntas orientadoras. Foi obtida autorização de um comitê de ética em pesquisa credenciado

Resultados:

Foram identificadas barreiras de a) disponibilidade, b) acessibilidade, c) psicossociais e d) burocráticas, e facilitadores em e) redes de apoio e f) estratégias de prevenção

Conclusões:

As barreiras de disponibilidade são especialmente importantes para os pacientes, uma vez que estão associadas a um déficit na oferta de serviços oncológicos oportunos. As redes de grupos de autoajuda destacam-se como facilitadores do processo terapêutico. A identificação de barreiras e facilitadores contribui para aprimorar estratégias de ação para um melhor atendimento aos pacientes oncológicos

Palavras-chave: barreiras ao acesso a serviços de saúde; equidade em saúde; unidades de tratamento oncológico

Introduction

In Chile and the rest of the regions of the Americas, there are millions of people who cannot access comprehensive health services, preventive programs, and achieve a healthy life. This places the Americas region as one of the most inequitable in the world. 1) In this regard, barriers in health care refer to the obstacles that affect access and use of essential services, so identifying them contributes to the development of strategies to eliminate them.2

Cancer is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality globally and has been associated with the aging of the population, and changes in lifestyles. 3) International studies show that people who suffer from cancer and their families are subjected to high levels of stress related to the care that they must implement quickly, uncertainty due to fear of recurrence after treatment, and/or assuming the economic costs caused by the disease. 4

In Chile, the high prevalence of cancer shows the need to strengthen prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care programs in this group. 3,5 In this context, cancer patients represent a vulnerable population, not only because of their condition. of health and emotional fragility, but also because of the family and social impact that it entails, and because of the predisposition to present complications associated with the disease. 6 Uribe et al. 7 also mention that these patients, once diagnosed, have serious difficulties in obtaining care, since in cancer patients there is an added lack of knowledge about cancer, and problems in organization and limitations. of specialized services. In this sense, this disease is understood not only as a public health problem, but as an important social and economic problem that affects patients, families, communities and the entire society. 3,5 As a global problem, cancer is distributed unevenly in the population, most frequently affecting people with low education and impoverished people, which justifies that the approach to this problem is comprehensive, and with a perspective of social determinants, by the States. 8

Cancer in Chile replaced cardiovascular diseases (CVD) as the main cause of death and ranks second in deaths caused by cancer in Latin America. 4

Since 2005, the Explicit Health Guarantees system (GES, by its Spanish acronym) has been in operation in Chile, which includes 14 conditions associated with cancer. The guarantee contemplates access, opportunity, financial protection and quality of care in the defined times for each pathology. The GES considers the coverage of care from suspicion, diagnosis, treatment and/or follow-up. The services must be provided in the network of providers established by the health insurance to which the patient belongs and respecting the deadlines for each case. 9,10

The National Cancer Plan in Chile includes “international recommendations that adequately represent the local reality from a focus on intersectionality and social determinants, based on theoretical-practical development and geographical and cultural relevance”. 9, p. 99) In addition, Chile has developed a public oncology network that considers the entire national territory based on six macro-regions, and whose purpose is to improve access and opportunity to care for patients. However, critical knots have been identified in the accessibility they consider, concentration and heterogeneity in the offer, and low cultural relevance. In this context, the northern macro region includes four Health Services: Arica, Iquique, Antofagasta, and Atacama. Where the greatest resolution is found in Antofagasta, which contains almost all the most complex treatment lines, and others of less complexity are located in the other Health Services. 10 Therefore, the plan contemplates reinforcing the five current centers by 2028, creating other complex and low complexity centers with a more equitable distribution throughout the country. 10

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the health system suffered drastic modifications to its operation, and there was a sharp drop in access to general care. 11 Being particularly serious for people who suffer from chronic or catastrophic diseases such as cancer, heart attacks or strokes that require specialized care. 12 This phenomenon occurred for several reasons, among them, the reorganization of the health system, users who did not consult for fear of contagion, the saturation of health centers for COVID patients which reduced the availability of hours for other diseases, the increase in care tasks for families due to the closing of schools, among many other factors. 13

Under this framework, the following research aims to analyze the barriers to health care in people diagnosed with cancer in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, in a commune in the Atacama region, Chile. To do this, it is approached from the interpretive paradigm, to collect the experiences of the people with cancer themselves and their caregivers. It is intended to be the beginning of a line of research that makes visible the reality of patients from areas far from large urban centers, which concentrate specialized care in Chile.

Methodology

The study was approached from the interpretive paradigm, qualitative methodology and content analysis. For Bardin 14 content analysis is a “set of communication analysis techniques aimed at obtaining indicators through systematic and objective procedures for describing the content of messages, allowing the inference of knowledge related to the conditions of production/reception. of these messages.” So, it allowed us to answer the question; What are the barriers to access to health care for people diagnosed with cancer in the commune of Vallenar, Atacama region? An individual in-depth interview was used given the sensitivity of the topic, the health status of the patients, and the difficulty in coordinating time slots that coincided with the informants. With a grid of guiding questions about their therapeutic trajectory in health services, since they were diagnosed, and progress in the treatment process. This is to identify the most significant access gaps that they have experienced in the care process.

The sample was intentional given the limited access to people undergoing cancer treatment; therefore, four patients with cancer of any type were considered, and their four caregivers, who in this case are key observers. The recruitment strategy consisted of them being contacted by a health official who acted as a liaison, and who facilitated contact with the main researcher to inform about the study and obtain informed consent from the participants. In this sense, eight of the 12 patients contacted refused to participate in the study, mostly due to being in fragile conditions, and because they distrusted scientific studies. The interviews were carried out in the homes of the informants, so a familiar and less threatening atmosphere was generated for them. As inclusion criteria, only adults were considered, and they were in stable emotional conditions. As an exclusion criterion, the participation of people in the terminal phase of the disease and/or palliative care was excluded. In the case of caregivers, the inclusion criterion is related to carrying out tasks of accompanying and caring for the person with cancer.

As criteria of rigor, the reliability of the data was ensured by recording the interviews in their entirety, a reliable transcription was made, the stories were anonymized using a code to identify the participants. The triangulation of the sample, as a dialectical cross-section of information, sought significant comparative relationships between patients and caregivers. On the other hand, the triangulation between researchers sought these significant relationships as suggested by Bardin, 14 through a first quick round or pre-analysis in which a large number of categories are identified, a second phase of projection of the analysis, in which A thematic line of interest is found and the categories are refined, and a third phase, in which the data is exploited in a logical and inductive way to meet the objectives of the study. The treatment and interpretation of the data was carried out collaboratively, between the main researcher, the secondary researcher, and a collaborating researcher. To this end, analysis meetings were held during the research, which allowed the work to be guided towards the proposed objectives. The initial interviews with the informants were complemented with new interviews, until the data were saturated, and no new information was identified. The findings were shared with the informants, who gave validity and credibility to what was stated. As a result, some aspects were reinforced, such as not having support during the therapeutic process. Finally, although the results are not transferable to other contexts due to the situated nature of the study, they expose a reality full of critical nodes that can be improved.

The ethical aspects of the research were evaluated and approved by a Research Ethics Committee (REC) accredited and resolved in CEI Nº26/2022, respecting the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on the integrity of the research.

Results

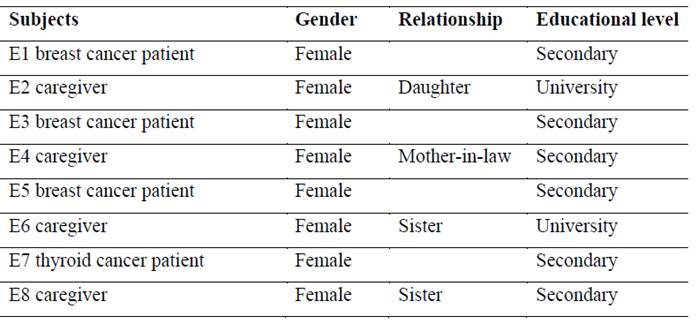

The sample considered eight subjects: four patients undergoing cancer treatment, and four caregivers. Table 1 shows that the informants are all female patients with secondary education, and whose caregivers have secondary and university education. The kinship relationships between the caregiver and the patient show that this role is fulfilled by direct or close family members; Two are her sisters, one is the mother-in-law (in-law), and one is the daughter. Finally, 3 out of 4 of the patients interviewed are being treated for breast cancer, while 1 out of 4 are being treated for thyroid cancer.

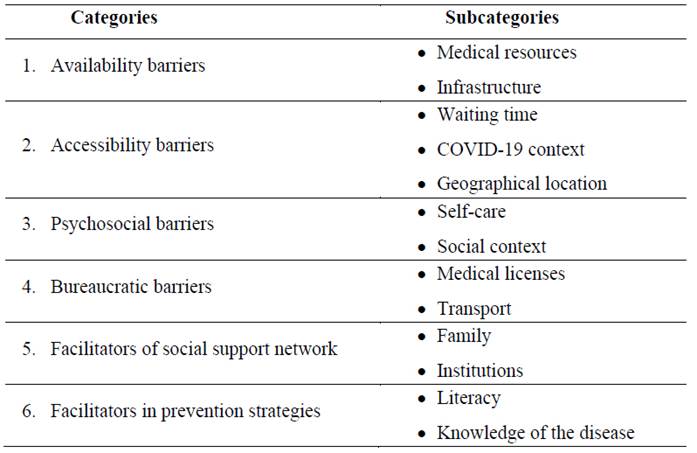

As a result of the interpretation of the data, six main categories and 13 secondary categories were established (Table 2)

Discussion

Availability barriers

Availability refers to the health services that patients who request them can effectively access, which involves the existence of the infrastructure, equipment, supplies, information, and human resources capable of producing the service.15,16 In In this sense, the informants express a permanent concern towards the health system, since the commune to which they belong does not have services available to be diagnosed and treated for cancer in a comprehensive manner. For this reason, people are referred to reference centers at the regional and national level, in order to comply with the GES, and with deadlines that vary for each type of cancer. 9 This aspect of the health system, is described by patients and their caregivers as a structural barrier, and they mainly emphasize the lack of human resources specialized in oncological care at the Vallenar provincial hospital:

Here in the commune, unfortunately We do not have the treatment service, here the most that can be done is diagnostic confirmation and beyond that, referrals to the programs that are, either in Copiapó, which is our referral network (E6).

Over the last few decades, Chile has been strengthening its public network of oncology providers, improving its infrastructure, and contributing to the development of specialized care centers, a strategy that at an international level has been considered relevant compared to the countries of the Organization for Cancer. Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In addition, it has sought to make resources more efficient, and formed this care network to facilitate coordination between professionals specializing in oncology. 17 However, it is still insufficient in infrastructure and specialized equipment, to which is added the deficit of doctors and radiotherapists when contrasting with other countries in Latin America and the world. 18 Added to this, inequality in the distribution of resources is observed in the concentration of specialists in the large urban regions of the country, leaving more extreme regions with low availability of oncological services. 9,10

Another aspect mentioned as a barrier to availability points to geographical inequity (place and space), 19 because in the place where the informants live, they do not have specialized oncological services, compared to other areas of the country. This situation is very important for patients, especially due to the deteriorated physical condition and fragility, which occurs as a side effect of chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment:

Here in Vallenar itself there should be a place where people can be treated, and not have to go out. To be able to go for an exam, because when you come out of your chemo you don't look well (E5).

Being a migrant due to cancer implies having to move from their places of origin to a place that receives them, under the condition of accessing diagnosis, treatment and/or follow-up. In most cases, treatment is associated with pain conditions, physical changes, and severe stress, which contributes to patients considering cancer as a complex and terrifying experience, above all, difficult to cope with away from their customs. and significant places.20

In the context of the pandemic, the deficit of health professionals, especially doctors and nurses, reached critical levels, especially in remote regions and areas, which adds to the lack of specialists and subspecialists, already mentioned. The global literature agrees that remote areas have limitations in the care of patients diagnosed with cancer, and that the existence of low-complexity oncology facilities in these areas does not necessarily solve universal coverage. This is because these facilities may be geographically accessible, but they do not have the capacity to deliver all oncological services and meet people's expectations. That is, it is possible to resolve geographical restrictions with low complexity centers, but cancer patients will always have to resort to higher complexity centers. 21-23

Accessibility barriers

Accessibility is associated with physical aspects such as distance, connectivity, and transportation time; organizational/administrative, related to administrative requirements for care, and with the modality to obtain hours and schedules of care, and financial; related to transportation costs, out-of-pocket expenses and loss of earnings at work. 15,16

The informants considered that the waiting times to obtain test results and obtain care hours in the suspicion phase are too long, which can delay the start of treatment. This negative perception is associated with the urgency of confirming or not, the diagnosis of cancer, which is why most patients opt for the private system to quickly escape the uncertainty that this causes:

Patients see themselves in the need to access private care, especially so that the results of examinations are more immediate, and thus begin treatment as soon as possible. Likewise, they mention that waiting times are still long, mammography results more or less at least a month, and biopsy as was still takes, much more than 10 days for the biopsy in Antofagasta (E1).

This sense of urgency described by the informants is related in the literature to the negative representation of cancer as a severe disease, in which people associate it with death, pain, the impact of the treatment on the body, and suffering. In addition, to the experiences of having known, or lived with people who became ill and died from cancer. 24

During the pandemic, the informants indicated a feeling of abandonment by the health system due to the difficulty of continuing with their usual treatment:

I took almost two months for care, when I was having my chemo every 21 days, there My “whole system was late (E5). My mother had a COVID test to enter the operation, and that test showed that she was positive for COVID, therefore her operation was delayed, and we had to wait for them to call her again when her quarantine ended (E2).

According to Cuadrado, “the pandemic overloaded the Chilean health system, and decreased access to oncological services”. 25, p.8) This coincides with the global literature that describes that health services during the COVID-19 pandemic fell abruptly and precipitously, especially in chronic and severe diseases. Despite efforts to seek alternatives, such as prioritization protocols or telemedicine services, difficulties in accessing care still occurred. Based on this, the pandemic favored the inequality that already existed in access to cancer diagnosis and treatment. Problem that is mainly related to the availability of a base in health services, for the delivery of services to this type of patients, 26 and the deficit of promotional and preventive actions to educate the community about healthy lifestyles and preventive examinations. 27

Psychosocial barriers

According to Vicente and López-Guillén, “psychosocial factors are personal conditions, the relational environment and the work environment, which act on the patient's motivation and attitude as conditioning factors in health and illness”. 28, p.55)

In relation to this point, there is a coincidence among the informants in their low level of self-care, since the majority do not have health self-care routines, and they go to the doctor only when they present symptoms or signs in their body. This described by them as; the appearance of “a little bean” or “a little ball.” In this regard, the role of the family in seeking specialized help has been fundamental:

I felt a small bean on my breast, and that alerted me, and I went for a mammogram (E1). My mother told us that she felt like a ball in her left breast, and we told her that it was better to have a mammogram, because she had not had one in 2020 (E2). When she had an illness, she was already about to die, she had just gone to the doctor, well like everyone else (E8).

This is consistent with Coutinho et al. 29) who describe that the motivation for the first consultation of cancer patients was to present a symptom. It also mentions that low adherence to preventive examinations is directly related to low educational levels, and to people without a family history of cancer. Low health literacy does not allow people to assimilate the severity or importance of undergoing routine examinations, a condition that influences high mortality rates from the disease in these groups. 29,30

The importance of access to preventive programs is one of the most effective public health measures to reduce mortality rates. However, a first step is to educate and raise awareness among the population to adopt self-care measures, and thus avoid the economic and social burden that cancer treatment means for families and the health system. 31,32

Bureaucratic barriers

Bureaucratic barriers in the health system correspond, according to Rodríguez et al., “to the set of technical-administrative strategies that are interposed to deny, delay or not provide services to its members”. 33, p.1948) In the health system These can generate delays in diagnosis, affect adherence to treatment and patient recovery. The informants describe situations such as the processing to obtain medical licenses, difficulties in obtaining medical appointments, and obtaining tickets to travel outside the commune:

We had some problems getting those licenses because we are patients of Vallenar, and we are treated at Copiapó. (…) sometimes the terms of my license did not coincide with a checkup with the oncologist, so I had to look for a doctor here so he could give me my license (E1).

Bureaucratic barriers have been described in other studies on cancer patients and are usually associated with problems in the design of care processes, poor administrative practices, lack of knowledge on the part of officials about the current regulatory framework, and lack of knowledge of users about the functioning of the health system. The latter is a critical point, considering that it prevents people from exercising their legitimate right to health. 34,35

Cancer is a disease that involves the possibility of anxious and depressive states, which reduces the ability of patients to adequately cope with the long process of diagnosis and treatment. 36 Patients face the physical and emotional burden that the disease entails, so the management of health processes must be efficient and comprehensive to promote timely care and recovery.

According to Arrivilla et al., 37 the health system is associated with bureaucratic itineraries in which care is not determined by people's needs and medical assessment, but by compliance with administrative and financial control regulations. Co-payments, moderation fees, delays in assigning appointments, authorizations for treatments and surgeries, among other procedures, become bureaucratic barriers that affect the opportunity, quality, and comprehensiveness of care. Consequently, it generates feelings of dissatisfaction and abandonment in the patient, while for doctors, these administrative problems are obstacles imposed by the system, in which bureaucratic issues prevail over the technical criteria of specialists. 38

Facilitators of social support networks

Support networks are understood as a protective factor in health, in this sense, social support emphasizes the conservation of the social relationships you have in your network. The network contributes with emotional support (affection), instrumental support (having direct help), and informational support (providing advice or guidance for solving problems)39 In this sense, the relatives of the informants mention that have actively participated in the decision to seek medical help for suspected cancer:

In the case of the little bean on her breast, we alerted her, and told her to go (E2).

On the other hand, the institutional oncological care network is a fundamental part of support for the entire family; however, the informants consider that psychological support has been late:

Psychological help should be at the time of receiving the diagnosis, when they tell you, that's where you're having trouble, imagine if you have a weak mind and my grandchildren and husband were affected, then it should be included in the family environment (E4).

According to Forgiony et al., the diagnosis of cancer begins a family crisis, in which routines, jobs, relationships, and roles are altered, which requires an adaptation process that will vary depending on the abilities and family skills. In this sense, for the patient; “The family can be both a generator of fear and uncertainty in the face of forecasts, and a source of support that accompanies and strengthens these changes” 40, p. 488) This exposes the need for specialized psychological intervention throughout the therapeutic trajectory. Which should include development of skills to cope with stress, family education and management of spirituality. 41

The reviewed literature highlights the dimension of patient support and care, considering it essential to develop skills for hospital staff to recognize and be sensitive to the patients' feelings and emotional needs. Along with this, provide immediate care to meet their physical and psychological needs, while the medical staff has a calming attitude regarding what the patient feels. 42

Another important social support network is the relationship and communication that is generated between the patients themselves, because they group and organize to solve problems related to coverage, and gaps in healthcare functioning:

We did the group with the girls, we are in communication, hey did this reach you? How long did it take you? We ourselves began to move on that side, so there I think it was faster, because if someone said call that number, because there they are going to give you information, one would call that number (E3).

Self-help groups fulfill fundamental functions in emotional, instrumental, and informational support 39 given that by being connected with other cancer patients, bureaucratic nodes are better resolved.

In relation to the loss of social roles due to the disease, the informants mention their concern about stopping working and their productive role:

An important problem is not being able to work, although I worked independently, that has affected me calmly ( a lot) emotionally, not having sustenance. My son was still at university, finishing his semester of medicine and that still affected me, because he required expenses for rent, transportation, although he had all his scholarships, but still. That really affected me a lot, not being able to contribute to him, apart from the conditions I was in, so I couldn't go out to work, so that's what affected me the most (E5).

Having a support network throughout life for any person is essential; it contributes to the satisfaction of human needs in the psychosocial sphere. This becomes more important when people cannot satisfy some needs in the biological or psychosocial sphere by themselves. Therefore, patients place great value on the support they receive from their families, friends, and community. 40

Facilitators in prevention strategies

Promotion is the strategy that provides communities with the necessary means to improve their health, and exercise greater control over it, which involves promoting healthy lifestyles and reducing the precursors of disease. In this sense, what health promotion seeks is to reduce the problems that favor the development of the disease through integrative proposals for health promotion and disease prevention. 43

Regarding the above, prevention strategies oversee primary health and are aimed at communities, promoting healthy lifestyles and with the aim of preventing people from getting sick. At this point, the informants mention that there is weak awareness regarding the prevention of the disease, and that it is necessary to strengthen education and information actions that contribute to reducing the incidence of this pathology:

I believe that, although they strongly promote getting a mammogram, but it is on the date that the disease is commemorated, I feel that there should also be more information regarding women who have cancer with their family members, with their offspring, because these people or in my case, me and my sisters and cousins are more likely to acquire this disease. Therefore, I feel that the age at which the examination is performed should be lower, in order to avoid future cancer diseases (E2).

Rodríguez et al. 44) describe a high rate of abstention from mammography and Pap smear exams in Chile, for detection of breast and uterine cancer respectively. In this aspect, primary care plays a fundamental role in the healthy health practices of patients, since, through health education, greater awareness of healthy behaviors such as maintaining physical activity and healthy eating is generated. In addition to reducing alcohol and tobacco consumption, considered essential to reduce the incidence of cancer. 45 In this regard, informed communities generate greater preventive awareness, so they are more likely to access treatment on time, given that for some, pain is the only symptom that motivates seeking help. 46,47

Conclusion

According to the purpose of the study, it was possible to identify the main barriers that the interviewed cancer patients experience as obstacles in care, in addition to identifying the facilitators. In order of importance, the availability barrier has been described as fundamental for cancer patients, as they have experienced resource deficits in care, especially the lack of oncology specialists. This limits the offer of services and access to care according to their needs and expectations. On the other hand, bureaucratic barriers explain the need to review the administrative processes associated with the care of these patients, since they lengthen waiting times and add greater stress to their fragile condition. Psychosocial barriers are interesting to highlight, to the extent that they are related to a low perception of self-care on the part of the informants themselves.

As facilitators, support networks have been described, with special emphasis on self-help groups, which, using WhatsApp as a means of communication, manage to resolve doubts, facilitate referrals, and guide themselves, forming virtuous collaboration groups that go beyond what is offered by the institutionality.

On the other hand, prevention programs for the active search for cancer in the initial stages are perceived as facilitating experiences, but they are unaware of the available offer. In this aspect, primary care plays an essential role in maintaining a supply of preventive and educational services, with universal coverage for the population.

Finally, the study also shows that in the geographical areas furthest from large urban centers, there are still great challenges in relation to the right to health and access to specialized care.

The study results constitute an important thematic and conceptual basis to delve deeper into the availability and accessibility of oncological care in remote or extreme regions of Chile. This can contribute to the development of strategies that improve the experience and the care system for patients and their families, considering differentiating aspects with large cities in our country.

REFERENCES

1. Hasell, J, Morelli, S, Roser, M. Recent trends in income inequality. En Vaccarella, S, Lortet-Tieulent, J, Saracci, R, Conway, DI, Straif, K, Wild, CP, editores. Reducing social inequalities in cancer: evidence and priorities for research. Lyon, FR: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566199/ [ Links ]

2. Houghton, N, Báscolo, E, Jara, L, Cuellar, C, Coitiño, A, Del Riego, A, Ventura, E. Barreras de acceso a los servicios de salud para mujeres, niños y niñas en América Latina. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022;46:e94. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2022.94 [ Links ]

3. Parra, SS, Petermann, FR, Martínez, MS, Leiva, AO, Troncoso, CP, Ulloa, N, et al. Cancer in Chile and worldwide: an overview of the current and future epidemiological context. Rev. Méd. Chile (Internet). 2020 (citado 2022 mar 23);148(10):1489-1495. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872020001001489 [ Links ]

4. Palma, SR, Lucchini, CR, Márquez, FD. Experiencia de vivir el proceso de enfermar de cáncer y recibir quimioterapia, siendo acompañado por una Enfermera de Enlace. Rev. méd. Chile (Internet). 2022 (citado 2023 oct 09);150(6):774-781. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872022000600774 [ Links ]

5. Martínez, MS, Leiva, AO, Petermann, FR, Celis, CM. How has the epidemiological profile in Chile changed in the last 10 years?. Rev. méd. Chile(Internet). 2021(cited 2022 jul 12);149(1):149-152. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872021000100149 [ Links ]

6. Bermúdez, YN, Osorio, JC. Sobrevivir al cáncer: Narrativas de un grupo de personas a partir de sus experiencias. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados (Internet). 2022(citado 2022 ago 03);11(2):e2792. doi: 10.22235/ech.v11i2.2792 [ Links ]

7. Uribe, C, Amado, A, Rueda, A, Mantilla, L. Cuidado paliativo en cáncer gástrico: barreras de acceso en Santander, Colombia. En Costa, AP, Ribeiro, J, Synthia, E, Faria, BM, editores. 7º Congresso Ibero-Americano em Investigação Qualitativa. Atas Investigação Qualitativa em Saúde. Vol. 2;2018, p. 1348-1353. Disponible en: https://ludomedia.org/publicacoes/livro-de-atas-ciaiq2018-vol-2-saude/ [ Links ]

8. Marmot, M. Social inequalities, global public health, and cancer. En Vaccarella, S, Lortet-Tieulent, J, Saracci, R, Conway, DI, Straif, K, Wild, CP, editores. Reducing social inequalities in cancer: evidence and priorities for research . Lyon, FR: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566199/ [ Links ]

9. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Plan nacional del cáncer 2018-2028. Chile: MINSAL; 2018. Disponible en: https://www.minsal.cl/wp- content/uploads/2019/01/2019.01.23_PLAN-NACIONAL-DE- CANCER_web.pdf [ Links ]

10. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Modelo de Gestión para el Funcionamiento de la Red Oncológica de Chile. Chile: MINSAL Biblioteca Digital Gobierno de Chile; 2018. Disponible en: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Modelo-de-Gestión-de-la-Red-Oncológica.pdf [ Links ]

11. Rojas, MP, Peñaloza, B, Soto, M, Téllez, A, Fábrega, R. Atención primaria en tiempo de COVID-19: desafíos y oportunidades. Temas de la Agenda Pública. 2022;17(154):1-19. Disponible en: https://politicaspublicas.uc.cl/publicacion/atencion-primaria-en-tiempos-de-covid-19-desafios-y-oportunidades/ [ Links ]

12. Pacheco, J, Crispi, F, Alfaro, T, Martínez, MS, Cuadrado, C. Gender disparities in access to care for time-sensitive conditions during COVID-19 pandemic in Chile. BMC Public Health (Internet). 2021(citado 2022 sept 10);21(1802):1-9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11838-x [ Links ]

13. Ministerio de Salud. Informe del impacto de la pandemia COVID-19 en las enfermedades no transmisibles en Chile; 2020. Disponible en: https://redcronicas.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022.03.07_INFORME-IMPACTO-COVID-EN-LAS-ENT-FINAL-1.pdf [ Links ]

14. Bardin, L. Análisis de contenido. 2da ed. España: AKAL Universitaria; 1996. [ Links ]

15. Levesque, JF, Harris, MF, Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health (Internet). 2013(citado 2023 mar 20);12(18). doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [ Links ]

16. Hirmas, MA, Poffald, LA, Jasmen, AS, Aguilera, XS, Delgado, IB, Vega, JM. Barreras y facilitadores de acceso a la atención de salud: una revisión sistemática cualitativa. Rev Panam Salud Publica (Internet). 2013(citado 2023 ene 15);33(3):223-229. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielosp.org/pdf/rpsp/2013.v33n3/223-229/es [ Links ]

17. Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. Estudios de la OCDE sobre salud pública en Chile, hacia un futuro más sano. Evaluación y recomendaciones. Chile: OCDE/MINSAL; 2019. Disponible en: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Revisión-OCDE-de-Salud-Pública-Chile-Evaluación-y-recomendaciones.pdf [ Links ]

18. Instituto de Salud Previsional de Chile-Estudio AICH. Atención y tratamiento del cáncer en Chile. Chile: ISAPRES; 2017. Disponible en: http://www.isapre.cl/PDF/Informe%20Cancer2017.pdf [ Links ]

19. Arcaya, MC, Arcaya, AL, Subramanian, SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action (Internet). 2015(citado 2023 ene 20);8(27106). doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27106 [ Links ]

20. Lostaunau, V, Torrejón, C, Cassaretto, M. Estrés, afrontamiento y calidad de vida relacionada a la salud en mujeres con cáncer de mama. Act. Psi (Internet). 2017(citado 2023 ene 22);31(122):75-90. doi: 10.15517/ap.v31i122.25345 [ Links ]

21. Liddell, JL, Burnette, CE, Roh, S, Lee, YS. Healthcare barriers and supports for American Indian women with cancer. Soc Work Health Care (Internet). 2018(citado 2023 ene 22);57(8):656-673. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2018.1474837 [ Links ]

22. Young, SG, Ayers, M, Malak, SF. Mapping mammography in Arkansas: Locating areas with poor spatial access to breast cancer screening using optimization models and geographic information systems. J Clin Transl Sci (Internet). 2020(citado 2023 ene 25);4(5):437-442. doi: 10.1017/cts.2020.28 [ Links ]

23. Faruqui, N, Bernays, S, Martiniuk, A, Abimbola, S, Arora, R, Lowe, J, et al. Access to care for childhood cancers in India: perspectives of health care providers and the implications for universal health coverage. BMC Public Health(Internet). 2020(citado 2023 mar 15);3;20(1):1641. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09758-3 [ Links ]

24. Palacios, XE, Gonzalez, M y Zani, B. Las representaciones sociales del cáncer y de la quimioterapia en la familia del paciente oncológico. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. (Internet). 2015(citado 2023 mar 15);33(3):497-515. doi: 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.3287 [ Links ]

25. Cuadrado, C, Vidal, F, Pacheco, J, Flores, SA. Acceso a la atención del cáncer en los grupos vulnerables de la población de Chile durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev Panam Salud Publica (Internet). 2022(citado 2023 ene 08);46:e77. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2022.77 [ Links ]

26. Graboyes, E, Cramer, J, Balakrishnan, K, Cognetti, DM, López-Cevallos, D, de Almeida, JR, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and health care disparities in head and neck cancer: Scanning the horizon. Head Neck (Internet). 2020(citado 2022 oct 25);42(7):1555-1559. doi: 10.1002/hed.26345 [ Links ]

27. Hasanpour, AD. Self-care Concept Analysis in Cancer Patients: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Indian J Palliat Care (Internet). 2016(citado 2022 sep 05);22(4):388-394. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.191753 [ Links ]

28. Vicente, JP, López-Guillén, AG. Los factores psicosociales como predictores pronósticos de difícil retorno laboral tras incapacidad. Med. segur. Trab (Internet). 2018(citado 2023 abr 13);64(250):50-74. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0465-546X2018000100050&lng=es . [ Links ]

29. Coutinho Medeiros, G, Santos Thuler, LC, Bergmann, A. Factors influencing delay in symptomatic presentation of breast cancer in Brazilian women. Health Soc Care Community (Internet). 2019(citado 2022 oct 20);27:1525-1533. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12823 [ Links ]

30. Rocha, SB, Andrade, L, Nihei, OK, Brischiliari, A, Hortelan, MD, Carvalho, MD, et al. Spatial distribution of breast cancer mortality: Socioeconomic disparities and access to treatment in the state of Parana, Brazil. PLoS One (Internet). 2018(citado 2022 oct 09);13(10):e0205253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205253 [ Links ]

31. Johnson, NL, Head, KJ, Scott, SF, Zimet, GD. Persistent Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake: Knowledge and Sociodemographic Determinants of Papanicolaou and Human Papillomavirus Testing Among Women in the United States. Public Health Rep (Internet). 2020(citado 2023 ene 08);135(4):483-491. doi: 10.1177/0033354920925094 [ Links ]

32. Maganty, A, Sabik, LM, Sun, Z, Eom, KY, Li, J, Davies, BJ, et al. Under Treatment of Prostate Cancer in Rural Locations. J Urol (Internet). 2020(citado 2023 ene 14);203(1):108-114. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000500 [ Links ]

33. Corrales, SM, Solórzano, SH. La importancia del consejo genético en el cáncer de mama. Med. leg. Costa Rica (Internet). 2020(citado 2022 oct 18);37(1):93-100. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1409-00152020000100093&lng=en . [ Links ]

34. Rodríguez, JH, Rodríguez, DR, Corrales, JB. Barreras de acceso administrativo a los servicios de salud en población Colombiana. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva (Internet). 2015(citado 2022 nov 12);20(6):1947-1958. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015206.12122014 [ Links ]

35. Lebaron, V, Beck, SL, Maurer, M, Black, F, Palat, G. An ethnographic study of barriers to cancer pain management and opioid availability in India. Oncologist (Internet). 2014(citado 2023 nov 20);19(5):515-22. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0435 [ Links ]

36. Villoria, LE, Salcedo, R. Frequency of depression and anxiety in a group of 623 patients with cancer. Rev. méd. Chile (Internet). 2021(citado 2022 oct 19);149(5):708-715. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0034-98872021000500708&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es [ Links ]

37. Arrivillaga, M, Malfi, DR, Medina, M. Atención en salud de mujeres con lesiones precursoras de cáncer de cuello uterino: evidencia cualitativa de la fragmentación del sistema de salud en Colombia. Gerencia y Políticas de Salud (Internet). 2019(citado 2023 ene 15);18(37):1-20. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.rgps18-37.asml [ Links ]

38. Uribe, CP, Amado, AN, Rueda, AP, Mantilla, LV. Barreras para la atención en salud del cáncer gástrico, Santander, Colombia. Etapa exploratoria. Rev Col Gastroenterol (Internet). 2019(citado 2023 mar 12);34(1):17-22. doi: 10.22516/25007440.353. [ Links ]

39. Granero, M, Volij, C. Influencia de los lazos sociales en la salud de las personas. Evid actual pract ambul (Internet). 2018(citado 2023 ene 20);21(1). doi: 10.51987/evidencia.v21i1.6797 [ Links ]

40. Forgiony, JS, Bonilla, NC, Moncada, AG, García, AC, Ardila, R, Kelly, F, et al. Desafíos terapéuticos y funciones de las redes de apoyo en los esquemas de intervención del cáncer. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacología y Terapéutica (Internet). 2019(citado 2023 ene 14);38(5):653-660. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=55962867021 [ Links ]

41. Ayala de Calvo, L, Sepúlveda, GC. Necesidades de cuidado de pacientes con cáncer en tratamiento ambulatorio. Enferm. Glob (Internet). 2017(citado 2023 ene 21);16(45):353-383. doi: 10.6018/eglobal.16.1.231681. [ Links ]

42. Calvo, JG, Narváez, PP. Experiencia de mujeres que reciben diagnóstico de Cáncer de Mamas. Index Enferm (Internet). 2008(citado 2023 ene 17);17(1):30-33. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S11 2-12962008000100007&lng=es . [ Links ]

43. Martínez, LS, Hernández, JS, Jaramillo, LJ, Villegas, JA, Álvarez, LH, Roldán, MT, et al. La educación en salud como una importante estrategia de promoción y prevención. Archivos de Medicina (Col) (Internet). 2020(citado 2023 mar 13);20(2):490-504. doi: 10.30554/archmed.20.2.3487.2020 [ Links ]

44. Rodríguez, CG, Espinosa, DV, Padilla, GF. Cáncer y acción preventiva en Chile: perfilando la abstención a la mamografía y papanicolaou. Rev. méd. Chile(Internet). 2021(citado 2023 mar 14);149(8):1150-1156. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872021000801150 [ Links ]

45. Olson, J, Cawthra, T, Beyer, K, Frazer, D, Ignace, L, Maurana, C, et al. Community and Research Perspectives on Cancer Disparities in Wisconsin. Prev Chronic Dis (Internet). 2020(citado 2023 ene 21);17:E122. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200183 [ Links ]

46. Condon, L, Curejova, J, Leeanne Morgan, D, Fenlon, D. Cancer diagnosis, treatment and care: A qualitative study of the experiences and health service use of Roma, Gypsies and Travellers. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) (Internet). 2021(citado 2023 mar 18);30(5):e13439. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13439 [ Links ]

47. Faruqui, N, Bernays, S, Martiniuk, A, Abimbola, S, Arora, R, Lowe, J, et al. Access to care for childhood cancers in India: perspectives of health care providers and the implications for universal health coverage. BMC Public Health (Internet). 2020(citado 2023 mar 22);20(1):1641. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09758-3 [ Links ]

How to cite: Torres Saavedra C, Campillay Campillay M, Dubó Araya P. Barriers and Facilitators of Health Care in People with Cancer in a Commune in Northern Chile: Qualitative Report. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2024;13(1):e3400. doi: 10.22235/ech.v13i1.3400

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. C. T. S. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14; M. C. C. in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 12, 13, 14; P. D. A. in 1, 2, 3, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Received: June 08, 2023; Accepted: November 12, 2023

texto en

texto en