Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.12 no.2 Montevideo 2023 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v12i2.3273

Original Articles

Social Representations of Women in the Pregnancy-Puerperal Cycle on Obstetric Violence

1 Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Brasil, mamoreira@uesc.br

2 Hospital Deraldo Guimarães, Brasil

Objectives:

To trace the biopsychosocial characteristics of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle and to analyze the social representations of these women on obstetric violence

Methodology:

Descriptive study, qualitative approach, guided by the Theory of Social Representations conducted in the period from September 2021 to April 2022, with 40 women assisted in a maternity hospital in Minas Gerais, Brazil. The data was collected through a script of semi-structured interview and the technique of free association of words. The characterization was analyzed by simple descriptive statistics, the semi-structured interview by the thematic content technique proposed by Bardin and the free word association technique by Iramuteq software

Results:

82.5 % of the participants had a range of 18 and 29 years, 77.5% self-identified as pardas (mixed race), 25 % had completed high school and 65 % reported income from 1 to 3 minimum wages. Regarding obstetric history, 52,0% had gestational age between 37 and 41 weeks, 70.0% had not planned pregnancy, 42.5% had been admitted for labor and 87.5% were monitored. Obstetric violence is represented by women in a superficial way with a focus on the physical and emotional dimension, being in some moments naturalized

Conclusion:

Obstetric violence is a serious problem experienced by the female public and the lack of knowledge can lead to naturalization, leaving them in a position of broad vulnerability

Keywords: pregnancy; postpartum period; obstetric violence; health care; nursing

Objetivos:

Traçar as características biopsicossociais das mulheres no ciclo grávido-puerperal e analisar as representações sociais dessas mulheres sobre a violência obstétrica

Metodologia:

Estudo descritivo, de abordagem qualitativa, norteado pela Teoria das Representações Sociais, realizado no período de setembro de 2021 a abril de 2022, com 40 mulheres atendidas em uma maternidade de Minas Gerais, no Brasil. Os dados foram coletados por meio de um roteiro de entrevista semiestruturada e da técnica de associação livre de palavras. A caracterização foi analisada pela estatística descritiva simples, a entrevista semiestruturada pela técnica de conteúdo temática proposta por Bardin e a técnica de associação livre de palavras pelo software Iramuteq

Resultados:

82,5 % das participantes possuíam faixa de 18 e 29 anos, 77,5 % intitularam-se pardas, 25 % tinham ensino médio completo e 65 % referiram renda de 1 a 3 salários-mínimos. Quanto à história obstétrica, 52 % possuíam idade gestacional entre 37 e 41 semanas, 70 % não haviam planejado a gravidez, 42,5 % haviam sido admitidas em trabalho de parto e 87,5 % estavam acompanhadas. A violência obstétrica é representada pelas mulheres de maneira superficial com enfoque na dimensão física e emocional, sendo em alguns momentos naturalizada

Conclusão:

A violência obstétrica é uma grave problemática vivenciada pelo público feminino e a falta de conhecimento pode levar à naturalização, deixando-as em posição de ampla vulnerabilidade

Palavras-chave: gravidez; período pós-parto; violência obstétrica; assistência à saúde; enfermagem

Objetivos:

Trazar las características biopsicosociales de mujeres en el ciclo gravídico-puerperal y analizar las representaciones sociales de estas mujeres sobre violencia obstétrica

Metodología:

Estudio descriptivo, de abordaje cualitativo, guiado por la teoría de las representaciones sociales, realizado en el período de septiembre de 2021 a abril de 2022, con 40 mujeres atendidas en una maternidad de Minas Gerais, en Brasil. Los datos fueron recogidos a través de un guion de entrevista semiestructurada y de la técnica de asociación libre de palabras. La caracterización fue analizada por la estadística descriptiva simple, la entrevista semiestructurada por la técnica de contenido temático propuesta por Bardin, y la técnica de asociación libre de palabras por el software Iramuteq

Resultados:

82.5 % de las participantes poseían rango de 18 y 29 años, 77.5 % se identificaron como pardas, 25 % poseían enseñanza media completa y 65 % refirieron renta de 1 a 3 salarios mínimos. En cuanto a la historia obstétrica, 52 % poseían edad gestacional entre 37 y 41 semanas, 70 % no habían planeado el embarazo, 42.5 % habían sido admitidas en trabajo de parto y 87.5 % estaban acompañadas. La violencia obstétrica es representada por las mujeres de manera superficial, con enfoque en la dimensión física y emocional, a veces naturalizada

Conclusión:

La violencia obstétrica es una grave problemática vivida por el público femenino y la falta de conocimiento puede llevar a la naturalización, dejándolas en posición de amplia vulnerabilidad

Palabras clave: embarazo; período posparto; violencia obstétrica; atención de salud; enfermería

Introduction

The social phenomenon called obstetric violence refers to the appropriation or invasion of the body and the reproductive processes of women. Represented by the pathologization and medicalization of natural events, it can occur at all stages of the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, as well as in situations of abortion, and most of the time, it may result in the loss of autonomy of the female population in relation to their bodies and sexuality. 1,2,3

It is known that violent obstetric practices can be influenced by several factors, namely the precarious training of professionals and structural difficulties and disorders in services. Driven by the desire to contribute to the proper development of their children, these women can be subjected to inappropriate conduct of health professionals involved in the process, expanding subjugation and low protagonism in pregnancy, delivery and puerperium, causing obstetric violence. 2

It is understood that obstetric violence is anchored in historical and political events of care for women, which was once performed exclusively in the household and by women of the community and, specifically, from the twentieth century, it changes to hospital obstetric care with great technological advancement and permeated by numerous interventionist practices that implied and still imply directly in the process of humanization of gestation, giving birth and birth, often resulting in obstetric violence. 3

Although considered to be a problem of great magnitude, obstetric violence remains unknown by women, who, when entering health services, are subjected to disrespectful and humiliating practices, with curtailment of their sexual and reproductive rights, information provided by health professionals, which leads them to submit to hierarchies of power and knowledge by the trust placed in the team and, often, to naturalize the violence suffered during care. 4,5

In this context, a study conducted with 276 women pointed out that 12.5 % of women recognized having suffered disrespectful practices during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, however, the authors call attention to the fact that violations of women’s rights during the analysis of the questionnaires were identified, but were not characterized as obstetric violence by the participants. In addition, research conducted with women in the postpartum period identified that most interviewees did not know how to define obstetric violence and that many had not previously heard the term. This fact points to women’s lack of knowledge about the problem as well as their sexual and reproductive rights. 6

Thus, obstetric violence becomes increasingly institutionalized, naturalized and invisible, in order to expand the multiple vulnerabilities to women who experience the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, in addition to developing feelings of incapacity, inferiority and devaluation, which will interfere in the form of gestation, giving birth and birth. 7,8 In this sense, this social phenomenon as an urgent issue, which affects many women worldwide, should be considered as a potent indicator of unequal and negative results during maternal-child care, fulfilled by dehumanization, disrespect, abuse and mistreatment in the fields of sexual and reproductive health and human rights. 9

Moreover, such violence occurs due to economic, social, cultural and generational reasons, leading to increased vulnerabilities and reduction in the rights guaranteed by law to women, making them reproductive bodies, which can be dominated, controlled and abused.5

In this line of thought, the following guiding question was defined: What are the social representations of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle assisted in a philanthropic maternity hospital on obstetric violence?

The study becomes relevant because it allows the understanding of the Social Representations of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle about obstetric violence and for contributing to the development of strategies capable of mitigating the current problem, present in the obstetric scenario. Thus, the objective of the research was to trace the biopsychosocial characteristics of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle and to analyze the social representations of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle on obstetric violence.

Method

This is a descriptive study, with a qualitative approach, guided by the Theory of Social Representations (TSR) that allows the understanding of the set of conceptions of the subject, group or society on a particular theme, subject, event, and representative conducts within their daily lives. 10

The research had the participation of 40 women, including 29 pregnant women and 11 postpartum women, assisted in a philanthropic maternity hospital located in Minas Gerais, in Brazil. The inclusion criteria for pregnant women were: being older than 18 years and having had prenatal consultations. Pregnant women with mental disorder and/or some cognitive impairment that hindered the understanding of the research and women in abortion situations were excluded.

With regard to the postpartum women, those who were older than 18 years old and those who did not have complications in the immediate postpartum period were selected and as exclusion criteria: postpartum women with pathological postpartum, those who had stillbirth or fetal loss, those who gave birth at home or on public roads and those who had a mental disorder and/or some cognitive deficit that hindered the understanding of the research.

The techniques used for data collection were a semi-structured interview script, involving open questions related to the theme researched and the technique of free association of words (TFAW) that allowed the individuals surveyed to provide information related to mental processes, through the explanation of words originated by two stimuli, respectively: “assistance received from health professionals during their pregnancy” and “assistance received from health professionals during their delivery”.

After approval by the Research Ethics Committee (REC), all study information was approximated and provided to the participants linked to the institution and accepted by signing the Informed Consent Form (ICF), with data collection between the months of September 2021 and April 2022, in a classroom, until there was theoretical saturation of the data. The criterion of simple sample was used for the definition of the quantitative of the participants.

All interviews were recorded on a digital device, with an average duration of 15 minutes. It should be noted that the participants received the option of research in the remote format, through the platforms Google Meet, Skype or Zoom, however, none of them opted for this mode. The transcription was made in the Microsoft Word, being analyzed by the thematic content technique proposed by Bardin, which describes the content of the messages and the indicators collected, through the observation of the communications. 11)

To perform the TFAW, the participants were guided about the maximum time for the response as two minutes for each stimulus and not answering elaborate verbal constructions. In total, 171 evocations referring to the first stimulus and 136 evocations resulting from the second stimulus were obtained.

The processing and analysis of the data were done through the software Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (Iramuteq), which aims to analyze terms spontaneously evoked to the head from an inducing stimulus and, when processed, allows the researcher to identify co-occurrences and connectivity between words. It is noteworthy that the use of the software in this study resulted in the construction of two similarity trees. 12

To maintain the anonymity of the participants, a list was presented with the name of flowers, allowing them to choose one that represented them, according to ethical precepts of resolutions No. 466/2012 and n. 510/2016. 13,14

Results

The study included 40 women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle. Regarding the biopsychosocial characterization, the analysis was processed by simple descriptive statistics. Of the participants, 17 (42.5 %) were in the reproductive period, from 24 to 29 years, considered young adults, and 31 (77.5 %) self-identified as of mixed race (pardas) and 26 (65 %) Catholic. Regarding the marital status, 25 (62.5 %) women were in a stable or married union. Regarding the level of schooling, it is noteworthy that only 10 (25 %) had high school, thus an important portion of this group is below high school; in addition, the family income of women remains low, in which 26 (65 %) reported receiving 1 to 3 minimum wages, the majority -13 (32.5 %)- occupying the role of housekeeper.

Regarding obstetric history, 15 (52 %) had gestational age between 37 and 41 weeks, 28 (70 %) had not planned pregnancy, 17 (42.5 %) had been admitted in labor, 35 (87.5 %) were monitored and 7 (17.5 %) had a history of mental illness before pregnancy, childbirth and/or protection.

Given the biopsychosocial characterization presented, obstetric violence can reach women differently, when related to issues of age, color/ethnicity, social class, marital status, level of education, presence of companion and obstetric history. Therefore, young, black, unmarried, low socio-economic women with low schooling are more likely to experience abuse, disrespect and abuse in health care services.

After the construction of the biopsychosocial characterization, there was the analysis of the interviews that allowed the construction of two categories: “(Lack of) knowledge of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle about obstetric violence” and “Naturalization of obstetric violence among women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle”.

It is understood that the little knowledge of women about their sexual and reproductive rights, combined with social issues, corroborates the imposition and acceptance of norms and values assigned by health professionals during care practices, which results in so-called obstetric violence, which can be represented as acts of a sexual, verbal and abandonment nature, unveiled through gross and unpleasant treatment, reprimands, cries, threats and humiliations, as described below:

Doctors that abuse, do things with patient (Aster).

I understand that it is when the nurses are rude to us (Almond flower).

Provide no assistance, help (Hortensia).

Obstetric violence is when the patient asks for help and the professional doesn’t help her when she needs it. (Begonia).

Moreover, obstetric violence is represented by women by practices based on purely personal decisions of health professionals and without any scientific evidence, such as episiotomy, Kristeller’s maneuver, repetitive vaginal touches and the use of oxytocin to speed up labor and actions not consented by users as follows:

Obstetric violence in my case and from what I understand, it's when you're in labor, the nurse comes to force the baby out. Wanting to take the baby out early (Dahlia).

I've heard that they apply the serum without informing the person to stimulate contractions (Creeping buttercup).

Cutting, pushing the baby a lot at the time of delivery. What I’ve already read was more or less this (Clove pink).

I’ve been touched several times (Lavender).

I've been touched 5-6 times since I got here (Calla çily).

Ignoring consent for certain things (...). There’s no consent from you and people do it, in this case the “obstetrician” does it (Waterliliy).

Passing through procedures not authorized by you (Lily).

The speeches refer to a disrespectful and violent care that reduces female protagonism and deconstructs the expectation of women for quality care, which can be extended to those who are completely unaware of the phenomenon, as pointed out below:

I’ve never heard of it (Touch-me-not)

I’ve no idea of what it is (False Christmas cactus).

Knowing what it is... definitely not! There are several types of violence, but I don't know how to define obstetric violence (Hibiscus).

I’ve heard through television, not where I live (Aster).

As can be seen, the lack of knowledge or low knowledge of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle about obstetric violence can affect their representations about this object, making them often naturalize them, especially when faced with procedures at the time of pregnancy and delivery, as shown below:

I wasn’t guided and didn’t know how it would be (Bush lily).

From here at the hospital no one guided me, but at home my mother had already told me how it would be and how it would happen (Iris).

I realize that some professionals are not interested in saying if we don't ask (Globe amaranth).

Doctors just evaluate and leave (Blanket flower).

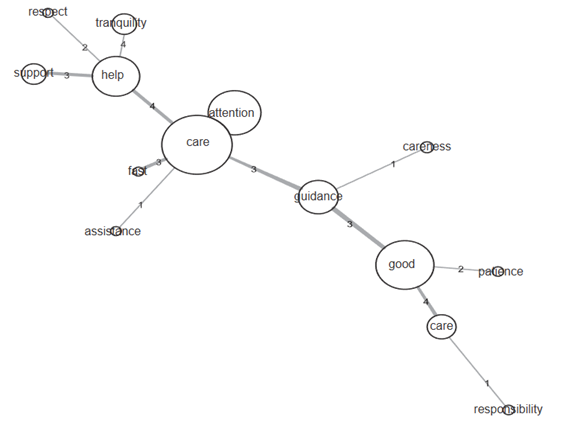

These social representations demonstrate the importance of working with good practices in childbirth care, with the permanent education of health professionals, with the knowledge of sexual and reproductive rights by women, in order to provide an opportunity for new symbologies to emerge during the experiences of the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, mitigating the phenomenon of obstetric violence, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Stimulus similitude tree “assistance received from health professionals during your pregnancy(ies)”. Minas Gerais (MG), Brazil, 2021-2022.

The terms most evoked “good”, “attention”, “care”, “help” and “guidance” demonstrate, on the other hand, positive care practices, which leads to believe in the need for professional training, from the entry of the pregnant woman in the health service to her discharge, extending qualification and humanization to the home environment.

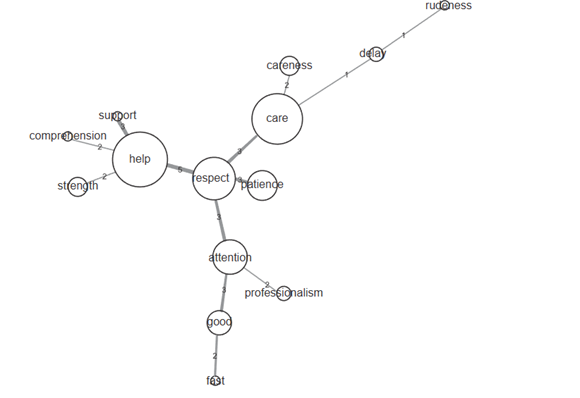

In addition, the evocations “respect” and “patience”, represented in Figure 2, reveal essential components of humanization in care during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, fundamental for the mitigation of any violent act against women. “Respect” permeates any relationship, especially the health professional relationship with the user and “patience” denotes the importance of a careful, respectful care, focused on the real needs of each woman who experiences the pregnancy cycle, important elements during the development of actions focused on good practices in the attention to gestation, give birth and birth.

Figure 2: Stimulus similitude tree “assistance received from health professionals during your delivery(ies)”. Minas Gerais (MG), Brazil, 2021-2022.

Despite the existence of reports of medicalized, interventionist and uncomfortable practices, women positively evaluate the care received. This is because, although obstetric violence is an old and recurring problem, violent conduct is seen as common, commonplace and should be performed during care. Thus, although they face obstetric violence practices, they are seen as secondary, necessary and inherent to care.

In this sense, it is noticed that women during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, although with little knowledge and naturalizing some typical care actions of obstetric violence, gradually unveil the symbologies about the phenomenon, denoting health education as a way to empower them, make them citizens of rights and with the power of choice.

Therefore, it is emphasized that violent obstetric practices are often difficult to be identified by the women involved, because they are understood and legitimized as indispensable, contributing to the naturalization of obstetric violence.

Discussion

The results of this study show the social representations of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle about obstetric violence, demonstrating that insufficient knowledge, on the part of some women, about this phenomenon increases female vulnerabilities, usurps the sexual and reproductive rights guaranteed by law and guaranteed through feminist movements and contributes to the occurrence of violence that affect the physical, emotional, social and inter-relational aspects of users.

In this sense, the performance of care practices in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle without scientific support are not identified and defined by women as disrespectful conduct. Studies show that the cultural conception of the gestation and delivery process is permeated by pain and interventions, practices that are not classified as obstetric violence by most women. 15

Moreover, young women, with low schooling, precarious family income situation and brown color, tend to be the most affected by violent care practices due to existing inequalities, demonstrating the importance of mitigating this type of violence in all scenarios of assistance to women, especially those in which there is difficulty in access and quality in health care. 16,17

In this sense, obstetric violence is related to gender issues, social inequality and care models that value unnecessary and disrespectful interventions with separation in the relationship between professional and woman to be cared for. Similarly, the naturalization of violent care behaviors is associated with the moral, conservative and myth dimensions of maternal love, worshipped by different religions, especially those linked to Catholicism, when women were compared to the Virgin Mary and therefore should be subjected to suffering for the benefit of their children, something questionable today. 18

Regarding the marital situation, this study show that most women remain in a stable or married union. It is known that the presence and active participation of a partnership during pregnancy and childbirth can be considered as a positive factor to curb violent practices and reduce the insecurity of women, which should be constantly stimulated by health professionals. 8 In addition, compliance with the Federal Law n. 11,108 of 2005, known as the Companion Law is also an essential element to curb obstetric violence within health services. 10

Concerning the biological profile, most women have full-term unplanned pregnancy. This datum points to the need of health services, especially primary care, to identify risk factors that can increase vulnerability situations, such as unsafe abortion, mental illness and obstetric violence. (15, 16, 17, 18, 19) Importantly, among the factors that result in hospitalization, there was a predominance of labor as the main cause, moment represented by great emotional and physical discharge by some women and considered a phase of greater propensity to practices characterized as obstetric violence. 15

Considering the psychological dimension, women did not report mental disorders or illness before pregnancy, childbirth and/or protection. Even with the findings, it is understood that the pregnancy-puerperal period represents a moment of emotional fragility, because, in addition to the biopsychosocial changes, the moment demands adaptations to the new life, being able to place women in mental vulnerability and in situations of obstetric violence, even in the face of positive previous experiences in pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium. 10

In this context, studies indicate that the greater the vulnerability of women, the more aggressive, violent and humiliating the care offered to them tends to be, in addition, the non-recognition and naturalization of obstetric violence by the female public are a problem of great complexity that demands immediate intervention. 20,21

Research conducted in Pakistan revealed that obstetric violence was manifested through ineffective communication, lack of supportive care, loss of autonomy, lack of resources, physical, verbal abuse and discrimination, being the primiparous and the poor the most mistreated by health services. It also evidenced that the lack of education on preparation for childbirth and postnatal care and lack of emotional support by the family network contributed to the expansion of obstetric violence. 22

Studies carried out in Latin America and Northern Europe also revealed the occurrence of obstetric violence practices, often demarcated by conducts, such as: limiting movement and choosing the position to give birth; keeping the parturients under prolonged fasting; performing episiotomy and maneuver of Kristeller, both proscribed; not allowing privacy and verbally disqualifying the power and autonomy of women. 23,24

With regard to the African continent, obstetric violence has high rates due to instrumental births performed in hospitals with disrespect and abuse of women, demonstrating that this phenomenon is global and affects the physical and mental health of these users within the health system. 25

Therefore, the problem has been recurrent worldwide in health care for women during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, being represented by verbal violence, through embarassing, offensive and humiliating comments by health professionals; by physical violence, such as the performance of episiotomy, Kristeller’s maneuver and the use of forceps for the withdrawal of the baby; and psychological violence, manifested by neglect, abandonment, blackmail and threats. 19,20

It is noticed that, in some situations, there is a naturalization of disrespectful conduct performed by health professionals due to women’s lack of knowledge about their rights and ways of coping with obstetric violence. 26 The lack of information and the fear of speaking and/or opposing violent practices, combined with the lack of recognition of their individuality and potential, makes women vulnerable to inhumane procedures, perpetuating obstetric violence. 8,16,17,26

Therefore, it is evident that obstetric violence is intricately related to gender violence and women’s lack of knowledge about their sexual and reproductive rights that make them naturalize and accept the violent practices received. Thus, to have a humanized assistance, it is essential to train and improve the professional through the inclusion of practices based on scientific evidence and that consider the sexual and reproductive rights of women. 21,22,23,24,25,26,27

Moreover, prenatal care performed by professionals who adopt humanized conducts, based on actions directed to the individuality of each woman, bringing information and independence, corroborates the decrease and even the extinction of obstetric violence. In addition, health education becomes indispensable for the population, since information is a powerful tool in combating violent practices. 16

Conclusions

The biopsychosocial characterization of those surveyed was mostly represented by women, aged 24 to 29 years, self-identified as of mixed race, Catholic, in a stable or married union, housekeeper, with low education level and family income between 1 and 3 minimum wages. As for obstetric systems, those with planned term pregnancy, admitted in labor, accompanied and with low history of mental illness before pregnancy, childbirth and/ or protection stood out.

The study showed that the social representations of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle on obstetric violence translate into neglect, reprimands, rudeness, threats, humiliations and abuse of power, anchored in gender issues, in the socioeconomic context in which women are inserted, resulting in a decrease in their autonomy, empowerment and protagonism.

In this context, the theme is little recognized and often naturalized in health services, and strategies for its mitigation are important, through health education, expanding the knowledge of women and especially the fulfilment of their sexual and reproductive rights. In addition, understanding the social representations on the subject from the users of the service is an important tool that will help in the development of practices that empower them and make them recognize their legal rights, resulting in improved health care.

Thus, the study is expected to encourage the adoption of practices that promote the appreciation of women as an active subject of the pregnancy-puerperal cycle through the acquisition of knowledge on the subject as well as the recognition of obstetric violence practices and that challenge professionals to perform a respectful care that returns the female protagonism.

Finally, a limitation of this study concerns the difficulty of understanding the TFAW by women with less education, although there were exercises with other stimuli not belonging to the research to understand the technique. However, this did not prevent achieving the proposed objectives due to the excellence of the data in the interviews.

REFERENCES

1. Sturza, JM, Nielsson, JG, Andrade, EP. Violência Obstétrica: uma negação aos Direitos Humanos e a saúde sexual e reprodutiva da mulher. Revista Juris Poiesis. 2020;23(32):380-407. Disponível em: http://periodicos.estacio.br/index.php/jurispoiesis/article/view/8643/47967016 [ Links ]

2. Galiano, JMM, Vazquez, SM, Almagro, JR, Martinez, AH. The magnitude of the problem of obstetric violence and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Women and birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2021;34(5):526-536. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.10.002 [ Links ]

3. Albuquerque, A, Oliveira, LGSM. Violência obstétrica e direitos humanos dos pacientes. Revista CEJ. 2018;(75):36-50 Disponível em: https://bdjur.stj.jus.br/jspui/handle/2011/126638 [ Links ]

4. Rodrigues, FAC, Lira, SVG, Magalhães, PH, Freitas, ALV, Mitros, VMS, Almeida, PC. Violência obstétrica no processo de parturição em maternidades vinculadas à Rede Cegonha. Reprodução & Climatério. 2017;32(2):78-84. doi: 10.1016/j.recli.2016.12.001 [ Links ]

5. Oliveira, LLF, Trindade, RFC, Santos, AAP, Araújo, BRO, Pinto, LMTR, Silva, LKB. Violência obstétrica em serviços de saúde: constatação de atitudes caracterizadas pela desumanização do cuidado. Rev. enferm. UERJ. 2019;(27):1-8. doi: 10.12957/reuerj.2019.38575 [ Links ]

6. Martins, ACM, Giugliani, ERJ, Nunes, LN, Bizon, AMBL, Senna, AFK, Paiz, JC, et al. Factors associated with a positive childbirth experience in Brazilian women: A cross-sectional study. Women and Birth. 2021;34(4):e337-e345. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.06.003 PMID: 32653397 [ Links ]

7. Oliveira, TR, Costa, REOL, Monte, NL, Veras, JMMF, Sá, MIMR. Percepção das mulheres sobre violência obstétrica. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line. 2017;11(1):40-46. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/revistaenfermagem/article/view/118767 [ Links ]

8. Ribeiro, DO, Gomes, GC, Oliveria, AMN, Avarez, SQ, Gonçalves, BG, Acosta, DF. The Epistemic Injustice of Obstetric Violence. Rev. Estud. Fem. 2020;28(2):1-12. doi: 10.1590/1806-9584-2020v28n260012 [ Links ]

9. Paula, E, Alves, VH, Rodrigues, DP, Felicio, FC, Araújo, RCB, Chamilco, RASI. Obstetric violence and the current obstetric model, in the perception of health managers. Texto & contexto enferm. 2020;(29):1-14. doi: 10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2019-0248 [ Links ]

10. Santos, ALM, Bckes, MTS, Smeha, LN, Freitas, HMB, Souza, MHT. Violência obstétrica: percepção dos profissionais de enfermagem acerca do cuidado. Disciplinarum Scientia. 2018;19(2):301-309. doi: 10.37777/2514 [ Links ]

11. Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo. São Paulo (SP): Edições 70; 2016. [ Links ]

12. Sousa, YSO. O uso do Software Iramuteq: Fundamentos de Lexicometria para pesquisas qualitativas. Estud. pesqui. psicol. 2021;21(4):1542-1560. doi: 10.12957/epp.2021.64034 [ Links ]

13. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Resolução n.º 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprovar as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Brasília: MS; 2012. Disponível em: https://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2012/Reso466.pdf [ Links ]

14. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução nº 510, de 7 de abril de 2016. Trata sobre as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisa em ciências humanas e sociais. Brasília: MS; 2016. Disponível em: https://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2016/Reso510.pdf [ Links ]

15. Palmarella, VP. Conhecimentos e experiências de violência obstétrica em mulheres que vivenciaram a experiência do parto. Enfermería Actual de Costa Rica. 2019;(37):66-79. doi: 10.15517/revenf.v0ino.37.35264 [ Links ]

16. Assis, JF. Interseccionalidade, racismo institucional e direitos humanos: compreensões à violência obstétrica. Serv. Soc. Soc. 2018;(133):547-565. doi: 10.1590/0101-6628.159 [ Links ]

17. Melo, BLPL, Moreira, FTLS, Alencar, RM, Magalhães, BC, Cavalcante, EGR. Violência obstétrica à luz da Teoria da diversidade e Universalidade do Cuidado Cultural. Rev. Cuid. 2018;13(1):1-16. doi: 10.15649/cuidarte.1536 [ Links ]

18. Palma, CC, Donelli, TMS. Violência Obstétrica em mulheres brasileiras. Rev. Psicol. 2017;48(3):216-230. doi: 10.15448/1980-8623.2017.3.25161 [ Links ]

19. Martins, FL, Silva, BO, Carvalho, FLO, Costa, DM, Paris, LRP, Junior, LRG, et al. Violência Obstétrica: Uma expressão nova para um problema histórico. Saúde Foco. 2019;(11):413-423. Disponível em: https://portal.unisepe.com.br/unifia/wp-content/uploads/sites/10001/2019/03/034_VIOL%C3%8ANCIA-OBST%C3%89TRICA-Uma-express%C3%A3o-nova-para-um-problema-hist%C3%B3rico.pdf [ Links ]

20. Madeira, DFP, Queiroz, MLS, Toleto, RL. Violência Obstétrica: a relação entre violação do direito à assistência obstétrica humanizada e o patriarcado. Saúde, Gênero e Direito. 2020;9(4):1-41. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpb.br/index.php/ged/article/view/51799 [ Links ]

21. Silva, SES, Gasperin, HG, Pontes, FS. A violência obstétrica e o despacho do Ministério da Saúde. Tensões Mundiais. 2021;17(33):205-228. Disponível em: https://revistas.uece.br/index.php/tensoesmundiais/article/view/3076/4476 [ Links ]

22. Nascimento, FC, Silva, MP, Viana, MRP. Assistência de enfermagem no parto humanizado. Rev. Prev. Infecç. e Saúde. 2018;4:6887. doi: 10.26694/repis.v4i0.6821 [ Links ]

23. Hameed, W, Uddin, M, Avan, BI. São mulheres desprivilegiadas e menos empoderadas privadas de cuidados de maternidade respeitosos: desigualdades nas experiências de parto em unidades de saúde pública no Paquistão. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249874 PMID: 33858009 [ Links ]

24. Swahnberg, K, Schei, B, Hilden, M, Halmesmaki, E, Sidenius, K, Steingrims-Dottir, T, Wijma, B. Patients experiences os abuse in health care: a Nordic study on prevalence and associated factors in gynecological patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(3):349-356. doi: 10.1080/00016340601185368 [ Links ]

25. Flores, YYR, Ibarra, LEH, Ledezma, AGM, Acevedo, CLG. Social construction of obstetric violence of Tenek and Nahuatl women in Mexico. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. 2019;53(9):1-7. doi: 10.1590/s1980-220x2018028603464 [ Links ]

26. Gebeyehu, NA, Adella, GA, Tegegne, KD. Desrespeito e abuso de mulheres durante o parto em unidades de saúde na África Oriental: revisão sistemática e meta-análise. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1117116. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1117116 PMID: 37153101 [ Links ]

27. Nunes, GFO, Melo, DEB, Espínola, MMM, Matos, KKC, Viana, LSS. Violência obstétrica na visão de mulheres no parto e puerpério. Perspectivas Online: Biológicas & Saúde. 2020;10(35):12-29. doi: 10.25242/8868103520202086 [ Links ]

How to cite: Moreira MAM, Souza MX de. Social Representations of Women in the Pregnancy-Puerperal Cycle on Obstetric Violence. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2023;12(2):e3237. doi: 10.22235/ech.v12i2.3237

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M. A. M. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; M. X. D. S. in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: February 27, 2023; Accepted: August 15, 2023

texto en

texto en