Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.12 no.2 Montevideo 2023 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v12i2.3131

Original Articles

Implications in caring for a sick family member: black women caregivers

1Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil, trielho_camilla@hotmail.com

2Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil

Introduction:

The disadvantages linked to the female gender are viewed in different aspects of life, through patriarchy. It is possible to understand that, in the case of black women, they are disadvantaged in the face of social structures, crossed by class, race and gender conditioning factors. In addition, it is seen that, in several cases, female caregivers, especially black women, do not voluntarily choose this role within the family environment.

Objective:

To identify the implications of care for a sick family member performed by black women caregivers considering their sociocultural conditions.

Methodology:

This work is an integrative review, whose search in the database was carried out in December 2020, where 3 results were found in the Web of Science database, 48 in the PubMed database and 29 in the LILACS database. After reading the abstracts of the 80 articles and applying the exclusion criteria, 7 articles were selected for full reading. Finally, 4 articles were included for analysis.

Results:

Only one study exclusively addressed women, and most were African Americans. Data indicate that, within a quilombola community, health care is passed on from the oldest to the youngest, as a symbol of respect for ancestral knowledge. In addition, it became evident that African-American caregivers of people with dementia need quality information about care and self-care, requiring resources in their community.

Conclusion:

It is possible to notice the inequalities according to the historical, political and cultural constructions caused, in order to differentiate men and women in family care. There is a need for debates that focus on the black population, especially caregivers, aiming at strategies to reduce their burden to care for sick family members.

Keywords: women; african americans; caregivers

Introdução:

As desvantagens ligadas ao gênero feminino são visualizadas em diversos aspectos da vida, mediante ao patriarcado. É possível compreender que, no caso de mulheres negras, estas se encontram desfavorecidas frente as estruturas sociais, atravessadas por condicionantes de classe, raça e gênero. Além disso, é visto que, em diversos casos, as cuidadoras mulheres, sobretudo, mulheres negras, não escolhem de forma voluntária este papel dentro da conjuntura familiar.

Objetivo:

Identificar as implicações do cuidado ao familiar adoecido realizado por mulheres negras cuidadoras considerando suas condições socioculturais.

Metodologia:

Este trabalho é uma revisão integrativa, cuja busca no banco de dados foi realizada em dezembro de 2020, onde 3 resultados foram encontrados na base de dados Web of Science, 48 na base de dados PubMed e 29 na base de dados LILACS. Depois de ler os resumos dos 80 artigos e aplicar os critérios de exclusão, 7 artigos foram selecionados para leitura completa. Finalmente, 4 artigos foram incluídos para análise.

Resultados:

Apenas um estudo abordou exclusivamente mulheres, e a maioria eram afro-americanos. Dados indicam que, dentro de uma comunidade quilombola, o cuidado com a saúde é repassado do mais velho para o mais novo, como símbolo de respeito aos saberes ancestrais. Além disso, ficou evidente que cuidadores afro-americanos de pessoas com demência precisam de informações de qualidade sobre cuidados e autocuidado, necessitando de recursos em sua comunidade.

Conclusão:

É possível notar as desigualdades de acordo com as construções históricas, políticas e culturais causadas, para diferenciar homens e mulheres no cuidado familiar. Havendo uma necessidade de debates que tenham como enfoque a população negra, principalmente as cuidadoras, visando estratégias para reduzir sua sobrecarga para cuidar de familiares em adoecimento.

Palavras-chave: mulheres; afro-americanos; cuidadores

Introducción:

Las desventajas vinculadas al género femenino se visualizan en diversos aspectos de la vida, a través del patriarcado. Es posible entender que, en el caso de las mujeres negras, ellas están en desventaja frente a las estructuras sociales, atravesadas por condiciones de clase, raza y género. Además, se observa que, en varios casos, las cuidadoras, especialmente las mujeres negras, no eligen voluntariamente este rol dentro del contexto familiar.

Objetivo:

Identificar las implicaciones del cuidado a un familiar enfermo realizado por cuidadoras negras considerando sus condiciones socioculturales.

Metodología:

Este trabajo es una revisión integradora, cuya búsqueda en la base de datos tuvo lugar en diciembre de 2020, donde se encontraron 3 resultados en la base de datos Web of Science, 48 en la base de datos PubMed y 29 en la base de datos LILACS. Después de leer los resúmenes de los 80 artículos. y aplicar los criterios de exclusión, se seleccionaron 7 artículos para su lectura íntegra. Finalmente, 4 artículos fueron incluidos para el análisis.

Resultados:

Solo un estudio se refería exclusivamente a mujeres, y la mayoría eran afroamericanas. Los datos indican que, en el seno de una comunidad quilombola, los cuidados de salud se transmiten de los más ancianos a los más jóvenes, como símbolo de respeto a los conocimientos ancestrales. Además, se puso de manifiesto que los cuidadores afroamericanos de personas con demencia necesitan información de calidad sobre cuidados y autocuidados y precisan recursos en su comunidad.

Conclusión:

Es posible percibir las desigualdades según las construcciones históricas, políticas y culturales provocadas, para diferenciar hombres y mujeres en el cuidado de la familia. Hay una necesidad de debates que se centren en la población negra, especialmente en las cuidadoras, con miras a elaborar estrategias para reducir su carga para cuidar a los familiares enfermos.

Palabras claves: mujeres; afroamericanos; cuidadores

Introduction

The work presented here was motivated by the discussion around black women family caregivers, which encompasses the dissertation entitled: Black women family caregivers: intersectional reflections for nursing. 1 It was developed from an integrative review conducted in 2020, which points out the implications of caring for the sick family member. It shows an overload in household chores, as well as in the execution of the care routine, being a conditioning factor for women.

Among the implications, there are those linked to the female gender that are visualized from maternity, work and marital relations, which affect financial independence, limiting desires, autonomy and choices in women’s lives. Such a set comprises the patriarchal structure that acts as a reality that comes from male domination, operating in the social layers and in the rights outlined as universal for women and men, promoting inequality between genders. In this sense, the social structure offers the task of caring for women, in which they are devalued, producing harmful feelings such as negativity in the lives of those who adopt this position of caregiver. 2

Accordingly, in several cases, the caregivers do not voluntarily choose this role within the family context. As a result, their options are restricted by limiting factors in the right to personal choice, lacking conditions to reduce the impact on the demand for domestic work, along with the care routine, as they provide care from feeding, hygiene, medications and dressings, among other issues that cover this care, such as affection and attention. 1

Feminist studies such as those by Davis 3 and Collins 4 point out that black women are disadvantaged in relation to white men and women, crossed by social class conditioning, fetishization of their bodies and subservience in their relations.

Gendered racism 5 operates as a tool about black women, exposing the divisions between race, class and gender that hierarchizes and subjugates them in the patriarchal order. Thus, an intersectional look highlights in family caregivers that oppressions should not be viewed separately, or as summative, but rather seen as overlapping. Data substantiate these implications, such as those from the Institute of Applied Economic Research 6 which shows that black women are in sets of jobs with low formal qualifications, precarious conditions, identifying that 57.6 % of domestic workers in the country are black.

Domestic work was performed by men and women in 2018, with an estimated 6.2 million individuals; in paid activities such as nannies, gardeners, day laborers and caregivers -around 5.7 million were women, a total of 92 %; and, of this, a total of 3.9 million were black. 7

Accordingly, it is necessary to identify the implications that lead to burden on the caregiver, as well as depression being linked to the female gender linked to care, analyzing the inequalities that place black women before the patriarchal structure and care in an imposing way. Therefore, carrying out a literature review on the topic of black women caregivers is important for knowledge and description of how the experiences lived by them are given, as well as the factors that imply.

In view of the above, it is understood that the care provided by black women encompasses the family, social, political and economic sphere in the form of subjection, in the face of a patriarchal system that harasses their experiences. Having said that, the objective of the study is to identify the implications of care for the sick family member performed by black female caregivers

Methodology

This is a bibliographic research typified as an integrative review. The six stages of the integrative review proposed by Mendes, Silveira and Galvão (8 were used: to identify the theme, in addition to formulating the guiding question; establish criteria for inclusion and exclusion of articles to integrate the present study, according to the databases that were used; to define the information to be extracted from the selected articles and categorize them, using a table to summarize the information that was found; to evaluate the articles that were included in this study; to interpret and discuss the results found; to elaborate the integrative review and the main results found.

The PICO strategy (Population; Intervention; Comparison and Outcomes) was used. The use of this strategy to formulate the research question in conducting review methods makes it possible to identify keywords, which help in locating relevant primary studies in the databases. 9 It should be noted that, depending on the review method, not all elements of the strategy are used; in this review, the comparison was not used. Thus, the first element of the strategy (P) consists of black women who are family caregivers; the second (I), to observe the implications in the care process; and the fourth element (O), to categorize the information found in scientific productions. The databases used were the Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information (LILACS), the United States National Library of Medicine (PubMed) and the Web of Science.

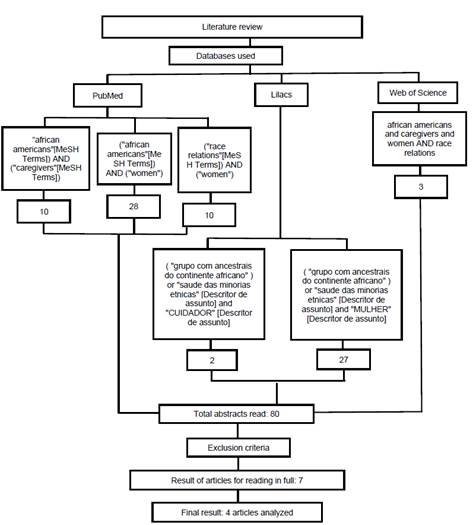

As displayed in Figure 1, the search took place in September 2020, using the following strategies: in PUBMED “african americans” (MeSH Terms)) AND (“caregivers” (MeSH Terms)), with 10 abstracts; (“african americans” (MeSH Terms)) AND (“women”), with 28 abstracts; (“race relations” (MeSH Terms)) AND (“women”), with 10 abstracts. In LILACS, they were: (“grupo com ancestrais do continente africano”) or “saude das minorias etnicas” (Subject descriptor) and “CUIDADOR” (Subject descriptor), resulting in two abstracts; (“group with ancestors from the African continent”) or “saude das minorias etnicas” (Subject descriptor) and “WOMAN” (Subject descriptor), resulting in 27 abstracts. On the Web of Science, the search was carried out in December 2020, with the following strategy: “african americans and caregivers and women AND race relations”, resulting in three abstracts.

Studies that addressed black female family caregivers in Portuguese and English were included. On the other hand, studies that only addressed care or health and did not mention the black female caregiver were excluded.

The 80 abstracts found were submitted to a primary selection by reading the titles and abstracts. The exclusion criteria were fully applied in the step that covered the analysis of titles and abstracts. Therefore, only seven met the needs of the study, but one was not found available or accessible via the Capes Periodicals Portal.

The six articles were read in full, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, resulting in four articles to compose the analysis corpus of this study. No temporal demarcation was used so that a greater number of results could be found. The four studies that were read in full in an attentive, investigative and in-depth way. The data were then categorized and organized using the Microsoft Excel program.

Regarding the contents, some categories were elaborated, namely: Complete reference, Year, Journal, Area of knowledge, Country where the research was developed, Country of the authors, Research design (quanti; quali; quanti-quali), Purpose of the study ; Research participants, Data collection techniques, Forms of analysis (descriptive, analytical, thematic, content and textual), Theoretical Framework (not necessarily a thinker, but concepts), Main results, in addition to: age of participants, gender, income , occupation, education, ethnicity/race, bond between caregiver and patient, care practices, preparation for care (experience), ancestry, historical aspects, organization for care, if you take care of other people, social support from whom, main results, propositions, relations with the house, conditions of possibility (violence, oppression, submission and subservience).

Therefore, we intended to collect all this information, but the articles had limitations regarding the desired information, based on the available results, they were examined for the synthesis of the contents according to Bardin's proposal, 10 which has as its primary function the critical unveiling. In these studies, the processes defined by Bardin were employed: Pre-analysis, material exploration and Treatment of results. 10

Content analysis is an empirical method, which consists of a set of instruments used to study opinions, attitudes, values and beliefs. In view of this, it is considered one of the main references for data analysis in qualitative research, being used in the analysis of texts and productions from different institutions, that is, evaluating results of techniques used in the collection of qualitative data. 11

Results

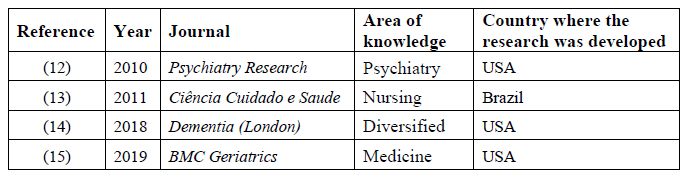

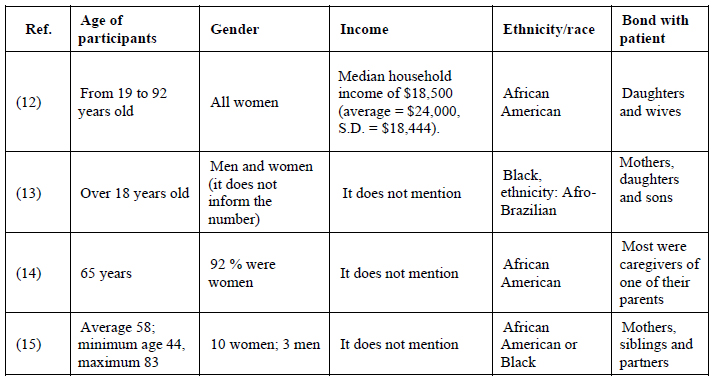

It was possible to observe that there is not a more frequent year, where studies are diverse in this regard, one being 2010, 12 one from 2011, 13 one from 2018, 14 and the most recent one from 2019. 15 Regarding the most recurrent countries in publication journals, the United States of America stands out. 12,14,15 Table 1 contains information about the characterization of the studies.

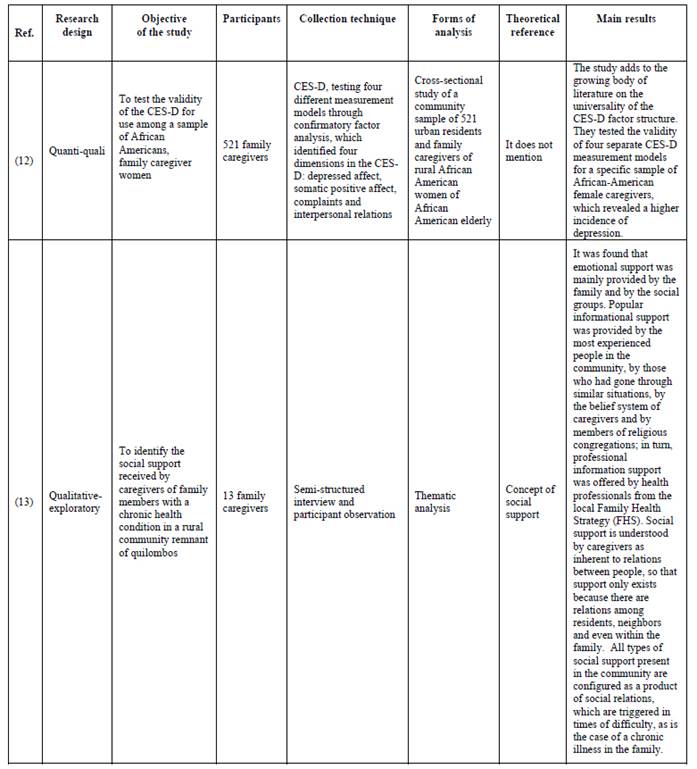

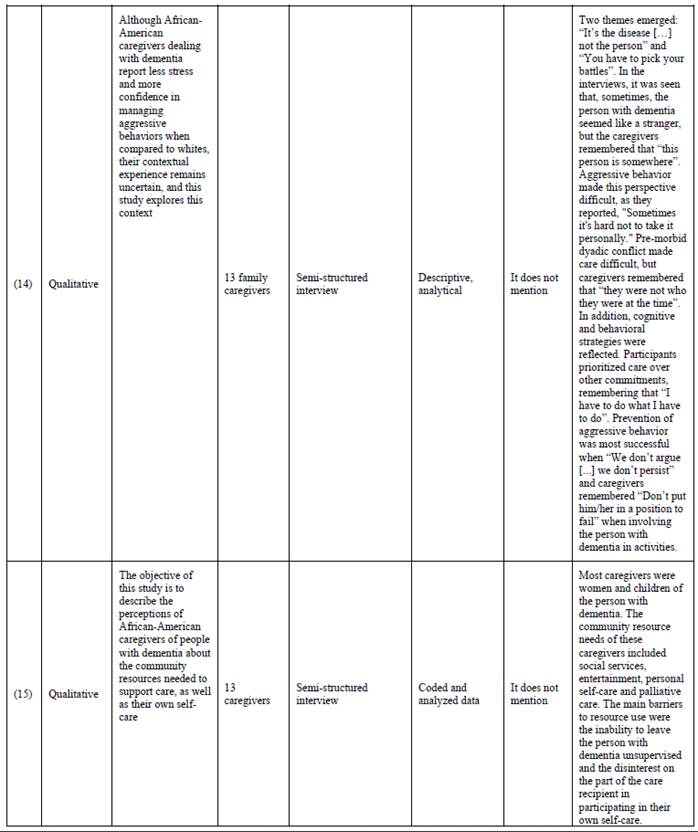

Regarding the methodological aspects, as shown in Table 2. As for the methodological characterization, the studies were mostly qualitative, totaling three studies,13-15 one of which was a quantiqualitative study. 12) Regarding the number of participants, most of them had 13 caregivers. 13-15) The most frequent technique used for data collection was the semi-structured interview. 13-15 Concerning the theoretical framework, most do not mention it. 12,14,15)t3 t4

Concerning the characterization of the participants, Table 3 highlights that the age ranged from 18 and 92 years. 12,13,14,15 There was only one study exclusively with women. 12) With respect to income, occupation, education, most do not mention them. Regarding ethnicity, most were African-American, 12,14,15) due to most studies being from the USA.

One of the implications of black female caregivers, according to a specific sample of African-American female caregivers, showed a higher incidence of depression. In another study, the implication was social support, through members of religious congregations, beliefs and professional information that were offered by health professionals from the local FHS.

In this quilombo, social support is understood as strengthening this experience from the exchange with caregivers who had gone through similar situations, residents, neighbors and even the family. Accordingly, the social support present in the community is configured as a product of social relations, which are triggered in times of difficulty, as is the case of a chronic illness in the family. Therefore, emotional and social support becomes a positive implication and is mainly provided by the family and local coexistence groups.

With regard to care practices, it is presented in the study 13 carried out in a community remnant of quilombos, in which science and health care are passed on from the oldest to the youngest, as a symbol of respect for knowledge ancestors that encompassed both the cause of disease and its treatment. The Afro-Brazilian communities existing in Brazil since enslavement, called quilombos, as a result of a series of implications, were not assured by the State in relation to supplies for good living conditions, including health services, and popular knowledge regarding the treatment of diseases is essential, as it is inserted as a relevant popular information support in this territory.

The organization of families for care is demonstrated by the fact that caregivers can participate in coexistence groups, as another family member assumes the care and activities developed in these groups, which provides caregivers with welcoming and appreciation, despite the stress related to the care of the sick family member, with a decrease in burden.13

In the study carried out in this rural community remnant of quilombos, it was noted that the emotional support received by the other components of the community 13 is in line with what historian Beatriz Nascimento stated in the documentary Ôrí, from 1989. She pointed out that “quilombo” is not an idea located in the past, but a cultural continuum of agglutination, understanding quilombo in its ideological sense, in the sense of aggregation, community and resistance for the recognition of humanity and preservation of the cultural symbols of black people. Caregivers reported that belonging to a geographic space in which they found the characteristics that culturally identified them produced a feeling of confidence, along with social support from health professionals, the community and family members. In the other studies, the forms of organization for care and social support were not mentioned.

In this study 13 it was also found that caregivers were unanimous in stating that it was always the family that they turned to in case of need for help, making clear the idea that responsibilities were shared. This way of understanding care as a family commitment is important, as it does not leave the responsibility of caring for only to the primary caregiver, giving him/her the opportunity to rest and not be burdened by solitary care. Regardless of the type of support provided, the family plays an essential role in caring for a sick family member, since, when care is shared by family members, the caregiver feels supported and can continue with his/her life, at the same time who cares for a sick family member.

Another study 15 highlighted that African-American caregivers of people with dementia needed quality information about care and self-care resources in their community. The idea of allowing volunteering among people living with family members with dementia arose from caregivers, who showed concern about leaving the person with dementia unsupervised, having discussed a support network through social networks, entertainment and personal self-care services and activities, which may include both the caregiver and the family member and provide rest. For this, it required engagement and awareness among owners in sectors other than human and social services, such as beauty salons and barbershops, among others prevalent in Chicago, where the study took place, involving the community and achieving success with health promotion and improvement in hypertension and cancer screening rates, especially in African Americans, thus suggesting the possibility that these businesses could be contracted to support people with dementia and their caregivers.

The results of the study, 15 because they are local, must be considered in the light of certain limitations. The findings may not generalize to other populations, including African American caregivers who live with higher or more diverse incomes or in rural communities. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the study was carried out in a clinic specialized in geriatric care and, even so, caregivers indicated a wide range of unmet needs. Although the sample size was small, it was diverse in terms of age, intensity of care and the relation of the caregiver with the person with dementia, showing similar information and resource needs from various caregivers and perspectives.

Another article 12 presents the Center for Epidemiologic Studies (CES-D) depression scale, which has been used extensively in community-based surveys to describe and explain the prevalence of depression in the general population. Moreover, questions have been raised as to its suitability for use among ethnic minorities, because of its factor variation. Employing a cross-gender and race approach, the validity of the CES-D was tested for use in a sample of 521 family caregivers of African-American women, urban and rural. Among the four measurement models tested using Weighted Least Squares estimation, the findings support research that identified four dimensions in the CES-D: depressed affect, positive affect, somatic complaints and interpersonal relations for the sample. In addition, a three-factor model (somatization) and a four-factor model were shown to be equivalent. In order to address issues of gender and race, such as sexism and racism, issues that make the prevalence of clinically relevant depression rates much higher than in other clinical and community-based samples, these difficulties were shown to be determinants in the role developed by family caregivers. The importance of considering the context of the lives of Afro-American women is perceived when thinking about coping with these problematizations, acting in the care process, overload and how caregivers operate in these conditions.

The author 12 also makes statements about the limitations of the study, about the relevance for future research and about considering subsample comparisons using a calculus and run approach. In order to fully examine the CES-D variance or invariance configuration, it would be important to consider other levels of equivalence, that is, variance or invariance in factor loadings, through an analysis of multiple groups as the study sample. Despite its limitations, our CES-D exam illustrates several strengths. First, our CES-D analyses were based a priori on the confirmatory approach as opposed to exploratory analyses. Second, we tested the validity of four separate CES-D measurement models for a specific sample of African-American female caregivers who revealed a higher incidence of depression.

In another publication 14 the perspectives of African-American caregivers on the aggressive behavior of family members with dementia are explored, with the main theme being the difficulty of not taking it personally, which implies analyzing the ability of caregivers to differentiate between the effects of dementia and the person they are caring for. Through this process of differentiation, they were able to cognitively reframe their perspectives and approach to caring for with compassion and patience, despite the substantial challenges they faced. As participants tried to balance priorities, a frequent refrain was “I have to do what I have to do”, which helped them keep care as the most important thing. Participants reported that preventing aggressive behavior was more successful when “We don’t argue”. In that study, they shared very similar techniques for maintaining person-centered care, thus suggesting that including these components could be an important way to support these caregivers.

Still in this, 14 it is noted that there was little diversity with respect to gender and relations. There was only one man and one caregiver who were partners; therefore, it was not possible to compare views between men and women or partners and non-partners. Another potential limitation of this study is that one person conducted both the interviews and the initial data analysis.

It is concluded, then, that these caregivers developed coping strategies well before assuming a caregiver role and, since then, have incorporated these strategies into the role. In the context of this model, the caregiving strategies that emerged from these caregiver interviews may reflect a lifelong approach to social interactions and attention to their own needs, which prepared them well for both caregiving demands. 14

The implications presented in the studies identify the subjectivity of the caregivers and the environment in which they are inserted, with similarities that reflect the conjuncture of their experiences, among them, meeting the social norms faced by many women. Exposure to the aggressiveness of family members who suffer from dementia, lack of information, lack of support to exercise care, depression and imposition in the socialization of the family situation, in which the woman and the man must follow their daily routine, as well as their roles, explicit in the care routine are also implications in this exercise of care. Some points that show this are the lack of information, the lack of public policies around the complexity of care, the understanding of this experience and its place within this context.

For this purpose, awareness is needed, as shown in studies that refer to social support as an implication that adds to the lives of caregivers. Therefore, for the African-American and black Brazilian women shown here, obtaining emotional and financial support and a support network, whether from other family members, the community and/or their partners, favors their experience as family caregivers.

Discussion

The publications intended in this work bring relevant implications for the performance of other research, such as social support in Afro-Brazilian communities. Due to the small number of studies on the topic in these communities that address family caregivers and their specificities. It is worth considering that the issue of black women as caregivers is linked to social and political relations that explain the structure that conditions these caregivers linked to female gender identity.

Caregivers needed community support and information to reduce the burden caused by the care process. Individual interventions helped to reduce psychological symptoms, having been oriented towards the problem of care, focusing on exploring and solving problems. Furthermore, showing social determinants, such as gender and race, implicated in clinically identified depression rates. Depression is currently one of the disorders with the highest incidence, as well as one of the pathologies that affects millions of people, requiring an emergency look by public health, with the burden of caregivers linked to this condition.16 It can be stated that the impairment in the quality of life of caregivers is related to the presence of depressive symptoms. These variables are closely related, the higher the depression indicator, the more affected the quality of life of the caregiver, or the worse the quality of life, the more vulnerable to depression the caregiver will be. 17

Accordingly, support for caregivers reduces the negative implications related to care, in the family structure, so that caregivers find support to carry out their demands and difficulties. In view of this, support provides a basis for family care, especially in times of disease potential, when care is intensified, representing the support network, that is, provided by health professionals, their community and/or family relations, being essential to ease the exhaustive routine of care. 18

The social determinants of health have also been highlighted as innovation and attention by Latin American authors. This is reflected as a political discussion in the face of neoliberal gestures that, in addition to an economic project, affect thinking and ways of life.19

In this sense, it is important to consider the social issues of gender and race in the health agenda. They are particularities that exceed individuality within social experiences. Therefore, black women, at work and in society, perform functions in the field of care that in the colonial period were represented by the production of life in families in colonial Brazil.

Crossed by social inequalities, arising from racism constituted in the period of slavery, this time is reproduced today in the social organization, privileging a portion of the population to the detriment of another that is neglected and undermined, from their sociocultural, socioeconomic and health conditions. 20

In view of this, manifestations of conscious and unconscious actions occur in the subjects, affecting living conditions in an expanded way, where racism is the author of these causes and conditions, annihilating bodies. This fosters patriarchy and regimes of oppression, above all, against racialized, black and indigenous women, determining social inequalities that are identified through social fragmentation, from opportunities, privileges, achievements and treatment in institutions.

Black movements have historically struggled in Brazil for better living conditions, aiming to increase the black population in universities, thus providing work and income. From this perspective, the National Health Policy for the Black Population is a pillar for better health care, discussions that break the hegemonic logic and its supremacist culture. Similarly, feminist studies that discuss equality between men and women and the way we are socialized, providing horizons for thinking about gender and opposing the western origin of feminism that does not contemplate black women, third-worldists, indigenous women, dissident bodies considered “others”. 21 Women’s experiences are multiple, but they follow society’s matrix of oppression, faced by personal, professional and social challenges, and there is a need for operations, discourses and actions that break with this socially structured imposed subalternity.

The implications to which women are subjected call into question male domination and care operating in an authoritarian manner. They aim at the importance of understanding the experiences of family caregivers in this matter, as well as their gaps, arising from the mechanisms of domination, critically analyzing the colonial order that affect black women.

Conclusion

In the context presented in this study about black women caregivers, it is notable that the discussion outlines inequalities in accordance with the historical, political and cultural constructions caused, in order to differentiate men and women in family care, as well as issues linked to gender, such as main markers of this social imbalance. This puts black women in conditions of subservience, conditioning elements of oppression, in the face of colonial matrices, but care, when it happens by choice, follows the path of affection, which is not consistent with that of imposition, socially structured for women.

We problematize this issue from the studies presented here, thinking about the possibility of deconstructing the roles that women should or should not play. This happened by addressing their care routine and the burden of caregivers, which, in addition, is related to social determinants of class, race and gender, in which it produces problems in their mental, physical and psychological health, limiting leisure time, as well as their quality of life.

The small number of articles found in the literature review to support the theme of the article was a limitation found in this study, since only four articles were used for analysis of results. In this sense, future studies in this field of knowledge are needed to provide new reflections in the scope of research and public policies.

In this sense, there are pillars that support ways of caring for based on social conditions, which lack public policies, debates that focus on black women caregivers, strategies to reduce their burden, based on their perspective and experience, generating care for those who care for.

REFERENCES

1. Coelho, CT. Mulheres negras cuidadoras familiares: reflexões interseccionais para a enfermagem (Dissertação de Mestrado). Pelotas: Universidade Federal de Pelotas; 2022. [ Links ]

2. Domingos, SC. Posição desvantajosa das mulheres negras na divisão sexual do trabalho e nos cuidados domésticos no âmbito familiar. Revista Contraponto (Internet). 2022 (cited 2022 oct 20);8(3):173-190. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/contraponto/article/view/117669 [ Links ]

3. Davis, A. Mulheres, raça e classe. 1ª ed. São Paulo: Boitempo; 2016. [ Links ]

4. Collins, PH. Aprendendo com a outsider within: a significação sociológica do pensamento feminista negro. Revista Sociedade e Estado. 2016;31(1):99-127. doi: 10.1590/S0102-69922016000100006 [ Links ]

5. Kilomba, G. Memórias da Plantação: episódios de racismo cotidiano. Editora Cobogó; 2019. [ Links ]

6. IPEA. Atlas da Violência 2013. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA-FBSP; 2013. [ Links ]

7. IPEA. Os desafios do passado no trabalho doméstico do século XXI: reflexões para o caso brasileiro a partir dos dados da PNAD contínua (Internet). Rio de Janeiro: IPEA; 2019 (cited 2023 May 12). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/9538/1/td_2528.pdf [ Links ]

8. Mendes, KDS, Silveira, RCCP, Galvão, CM. Revisão integrativa: método de pesquisa para a incorporação de evidências na saúde e na enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enfermagem. 2008;17(4):758-764. [ Links ]

9. Casarin, ST, Porto, AR, Gabatz, RIB, Bonow, CA, Ribeiro, JP, Mota, MS. Tipos de revisão de literatura: considerações das editoras do Journal of Nursing and Health. Journal of nursing and health. 2020;10(5):e20104031. [ Links ]

10. Bardin, L. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70; 2017. [ Links ]

11. Sampaio, RC, Sanchez, CS, Marioto, DJF, Araujo, BCS, Herédia, LHO, Paz, FS, et al. Muita Bardin, pouca qualidade: uma avaliação sobre as análises de conteúdo qualitativas no Brasil. Revista Pesquisa Qualitativa. 2022;10(25):464-494. [ Links ]

12. Rozario, PA, Menon, N. An examination of the measurement adequacy of the CES-D among African American women family caregivers. Psychiatry Research. 2010;179(1):107-112. [ Links ]

13. Silveira, CL, Budó, MLD, Ressel, LB, Oliveira, SG, Simon, BS. Apoio social como possibilidade de sobrevivência: percepção de cuidadores familiares em uma comunidade remanescente de quilombos. Ciência, Cuidado e Saúde. 2011;10(3):585-592. [ Links ]

14. Hansen, BR, Hodgson, NA, Gitlin, LN. African-American caregivers’ perspectives on aggressive behaviors in dementia. Dementia (London). 2018;18(7-8):3036-305. [ Links ]

15. Abramsohn, ME, Jerome, J, Paradise, K, Kostas, T, Spacht, WA, Lindau, ST. Community resource referral needs among African American dementia caregivers in an urban community: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics. 2019;19(311):1-10. [ Links ]

16. Dourado, DM, Rolim, JA, Ahnerth, NMS, Gonzaga, NM, Batista, EC. Ansiedade e depressão em cuidador familiar de pessoa com transtorno mental. Estudos Contemporâneos da Subjetividade. 2018;8(1). Disponível em: http://www.periodicoshumanas.uff.br/ecos/article/view/2377 [ Links ]

17. Sampaio, LS, Santana, PS, Silva, MV, Sampaio, TSO, Reis, LA. Qualidade de vida e depressão em cuidadores de idosos dependentes. Revista APS. 2018;21(1):112-121. [ Links ]

18. Cardoso, CA, Noguez, PT, Oliveira, SG, Porto, AR, Perboni, JS, Farias, TA. Rede de apoio e sustentação dos cuidadores familiares de pacientes em cuidados paliativos no domicílio. Revista Enferm. Foco. 2019;10(3):70-75. [ Links ]

19. Borghi, CMSO, Oliveira, RM, Sevalho, G. Determinação ou determinantes sociais da saúde: texto e contexto na América Latina. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde. 2018;16(3):869-897. Disponível em: http://revista.cofen.gov.br/index.php/enfermagem/article/view/1792/579 [ Links ]

20. Santos, GSR dos, Paulino, GB, Rocha, FM, Luz, RS da, Santos, GVR dos, Dumas, GB, et al. Política Pública, Saúde E Racismo: Revisão Integrativa Da Literatura. Práticas e Cuidado: Revista de Saúde Coletiva. 2022;3:e14537. Disponível em: https://homologacao.revistas.uneb.br/index.php/saudecoletiva/article/view/14537 [ Links ]

21. Moron, JG, Salomão, JS. Representação Vs. Representatividade: Estudos Feministas No Brasil Na Pós-Graduação. Revista Conjuntura Global. 2022;11(1):41-60. doi: 10.5380/cg.v11i1.82573 [ Links ]

How to cite: Trindade Coelho C, Griebeler Oliveira S, Eisenhardt de Mello, F. Implications in caring for a sick family member: black women caregivers. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2023;12(2):e3131. doi: 10.22235/ech.v12i2.3131

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. C. T. C. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; S. G. O. in a, b, c, d, e; F. E. M. in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: November 16, 2022; Accepted: May 23, 2023

texto en

texto en