Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.11 no.2 Montevideo Dec. 2022 Epub Dec 01, 2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v11i2.2901

Dossier: Qualitative methods for social transformation | Original Articles

Feelings and Emotions Present in the Experiences of Pregnant Women and Donors with Chagas Disease in Chile

1 Universidad de Tarapacá, Chile, ngarrido@academicos.uta.cl

2 Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Chile

Objective:

This article describes the feelings related to the experience of Chagas disease in the Chilean regions of Tarapacá, Atacama and Metropolitan. The study focused on feelings and emotions as subjective experiences of pregnant women and blood donors in relation to the Chagas health problem, aspects that underlie their interaction with the social and health system.

Method:

A qualitative methodology was employed and techniques such as in-depth interview, semi-structured interview and focus groups were used. A total of 176 nationals and migrants participated.

Results:

The relevance of fear and guilt, mainly experienced by women, was observed. Lack of knowledge and misinformation in the process of diagnosis and treatment and the meanings attributed to the disease are determinants of care.

Conclusions:

For the understanding of health processes and improvements in the health system, feelings and emotions around this problematic must be known. Considering subjectivities allows humanizing the strategies for approaching Chagas disease.

Keywords: Chagas disease; feelings; qualitative research; pregnant women and donors.

Objetivo:

Este artículo describe los sentimientos relativos a la experiencia de la enfermedad de Chagas en las regiones chilenas de Tarapacá, Atacama y Metropolitana. El estudio se enfocó en los sentimientos y emociones como experiencias subjetivas de mujeres gestantes y donantes de sangre en relación con la problemática de salud de Chagas, aspectos que subyacen en su interacción con el sistema social y sanitario.

Método:

Se empleó una metodología cualitativa y se utilizaron técnicas como entrevista en profundidad, entrevista semiestructurada y grupos focales. Participaron 176 personas nacionales y migrantes.

Resultados:

Se observa la relevancia del temor y la culpa, experimentada principalmente por las mujeres. El desconocimiento, desinformación, en el proceso de diagnóstico y tratamiento y los significados atribuidos a la enfermedad son determinantes de la atención.

Conclusiones:

Para la comprensión de los procesos de salud y las mejoras en el sistema de salud, se deben conocer los sentimientos y emociones en torno a esta problemática. Considerar las subjetividades permiten humanizar las estrategias de abordaje del Chagas.

Palabras claves: enfermedad de Chagas; sentimientos; investigación cualitativa; mujeres gestantes y donantes.

Objetivo:

Este artigo descreve os sentimentos relacionados com a experiência da doença de Chagas nas regiões chilenas de Tarapacá, Atacama e Metropolitana. Os sentimentos e emoções como experiências subjetivas de mulheres grávidas e doadores de sangue em relação ao problema de saúde da doença de Chagas, aspectos que fundamentam sua interação com o sistema social e de saúde.

Método:

Uma metodologia qualitativa foi utilizada e técnicas como entrevistas em profundidade, entrevistas semi-estruturadas e grupos de foco foram utilizadas. Um total de 176 nacionais e migrantes participaram.

Resultados:

Observamos a relevância do medo e da culpa, principalmente experimentada pelas mulheres. Falta de conhecimento, desinformação, no processo de diagnóstico e tratamento e os significados atribuídos à doença são determinantes para o cuidado.

Conclusões:

Para a compreensão dos processos de saúde e melhorias no sistema de saúde, os sentimentos e emoções em torno deste problema devem ser conhecidos. Considerando as subjetividades, é possível humanizar as estratégias para lidar com a doença de Chagas.

Palavras-chave: doença de Chagas; sentimentos; investigação qualitativa; mulheres grávidas e dadores.

Introduction

Chagas disease is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite that can be transmitted through several ways. One of them is through hematophagous insects that inhabit the American continent from the United States to the southern cone. Another is through the transfer of the parasite by means of the contaminated feces of the vector known as vinchuca, bedbug, kissing bug, barbeiro or pito 1 through the skin and, orally, through food and liquids contaminated with the depositions of these insect vectors.2 It is also transmitted through the placenta during pregnancy, or due to uncontrolled blood transfusion or organ transplantation. Complications caused by the parasite are mainly associated with cardiovascular, digestive and, in some cases, neurological problems. However, it is estimated that only 30 % of infected persons will develop any complications. Undoubtedly, timely diagnosis and treatment are key for the prevention of vertical transmission (mother-child) and for a satisfactory quality of life for people living with this condition. 3,4

Much progress has been made in reducing the number of infections; proof of this is that Chagas disease has gone from a worldwide prevalence of more than 17 million people in the 80's of last century to 6 to 7 million people today. 5 Today, this health problem is considered to be of a global nature due to urbanization, climate change and human mobility, which have changed the profile of American trypanosomiasis; however, in the past it was considered endemic to the American and rural continent. 2,6 - 10

In Chile, progress has been made in vector control, universal screening for transplants and in creating the conditions for universal screening of pregnant women in public or private health care facilities; however, progress still needs to be made to achieve screening of all pregnant women in health care. Although diagnosis and treatment are universal and guaranteed by the health system, it is estimated that more than 120,000 people are carriers of the disease in the country, and progress still needs to be made in identifying those affected by Chagas disease. 11 To better address the problem, the Plan for the Control and Prevention of Chagas Disease was created in Chile in 2014 by the National Ministry of Health (MINSAL). In this context, the technical standard number 162-2014 set as a goal for the year 2017 the screening of 100 % of pregnant women, however, this figure only reaches 64 % of the target population by the year 2020, at the national level, with a lower percentage in the southern part of the country. 12 The latter is especially worrisome because the most efficient way to avoid vertical transmission of Chagas disease is to identify the parasite in women of childbearing age and treat them before future pregnancies, which effectively reduces transmission through the infected placenta. 1 This, together with the 1.2 % prevalence of the disease, constitute the most important problems related to Chagas disease in Chile. 13

It is evident that strategies to reduce the number of Chagas disease cases need to transcend the traditional perspectives of biomedical observation of the condition, going from zoonotic and clinical studies 14-16 to dimensions that incorporate the emotions and feelings of people in relation to Chagas disease. 10 In this regard, this study has considered the need for health care with a comprehensive approach where feelings and emotions are raised as fundamental aspects for the health of people. 17 The feelings and emotions of people with Chagas disease with respect to the disease hinder or favor adherence to treatment and interaction with health teams at different levels of health care. (17, 18) Ventura García et al. 19 identify that fear of diagnosis is established as an important barrier to access health services, and this emotionality is also linked to latent risk. 20 In the approach to the problem of Chagas disease and migrant pregnant women, according to Avaria and Gómez, fear and guilt are closely related to the diagnostic processes linked to pregnancy. (21

The lack of information and knowledge about Chagas aggravates the negative emotions of those who suspect they have the disease. 3 Fear, sadness and feeling bad, according to the reports of possible carriers, are negatively affected by the discrimination that people diagnosed with T.cruzi have reported suffering 22 discomfort and the experience of a low quality of life and depression emerge especially in chronic cases and people who develop cardiac involvement. 6,23 The barriers faced by people, especially migrants, are related to the difficulties in accessing health care, the side effects of treatments, the need to address the complexities of mental health due to the possibility of developing depression and the barriers related to the lack of knowledge of health teams. 24 Research shows the violation of rights experienced by people with Chagas as workers, students, etc., and alarmingly, as users of health systems. 6, 25)

Situations such as the one reported by Van Wijk et al. are of special attention, an interviewee shared the experience of being told by a health worker when he went to donate blood: “your blood is useless, we are going to burn it, and you are going to die of Chagas disease, go to the doctor”. (3 This type of cases observed in the Colombian context and in others, show prejudices, tensions and asymmetries in which the concerns, feelings and emotions of the people are not incorporated in the strategies for dealing with Chagas disease.26 The role of health technicians and professionals is fundamental in the diagnosis and treatment process. In these critical stages, people require emotional support and place great value on the communication they establish with technicians and professionals, especially with members of the health care team. An example of this was reported by Jimeno et al. in the testimony collected by them: “At each check-up, the doctor carefully explained to me how I should take the pills, how Chagas disease comes and how I should take care of myself, now I am healthy, now I am calm”. (6 This global health problem is a challenge that should actively involve health teams and the people affected through social organization.27,28

In this scenario, health workers can contribute to detection and adherence to treatment, incorporating family and community approaches in order to connect with people. Uncertainty and lack of knowledge about Chagas disease decrease when the family and community environment is used to intervene with people. (21) The data show the relevance of health teams working not only with the affected person directly, but also, and this is significant, with their family environment, friends, and community referents. Jimeno et al. add that the family has a great psychosocial-emotional impact on living with, resolving or eradicating the disease. (6 Their research group detected, for example, that for women with Chagas disease, it was fundamental to keep themselves in good health conditions to take better care of their children and family. Mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, friends, and other relatives are an integral part of the stories of support and emotional accompaniment that, according to the people observed, have helped them to be diagnosed and treated. 28 In this sense, successful experiences in dealing with Chagas disease are linked to the individualization of people, i.e., the consideration of their family and social identity crossed by subjectivities and emotions,21 especially, but not exclusively, in migration contexts. Sociocultural understanding is relevant, as well as the articulation of people through the community approach, empowered peers or through associativity. 21,25,26,28

On the other hand, regarding Chagas disease, the evidence indicates that the social components of the problem are scarcely considered, with the biomedical approach being the most predominant. There is little or no incorporation of interpretative perspectives that consider the experience of affected persons in the design of intervention strategies in Chile. 2 Although the guidelines of the National Plan for the Prevention and Control of Chagas Disease through technical standard n.° 162 of 2014 and its consequent operationalization in the Procedural Manual for the Care of Patients with Chagas disease 29 consider the family context of the person with Chagas disease, this link is established from the active search for the detection of T.cruzi. However, it is necessary to broaden the understanding of Chagas disease, considering the subjective components that determine access and diagnosis, and people's adherence to treatment.

The general objective of the research project was to analyze the experiences and meanings of Chagas disease in national and foreign women and men and in health care teams. Considering the current diagnosis, care and follow-up of Chagas disease in the regions of Tarapacá, Atacama, and Metropolitan. Thus, improving people's health through the implementation of the Technical Standard.

With all the above, we intend to justify, through this paper, the need to investigate the aspects that involve the feelings and emotions of the people who experience the phenomenon of Chagas disease in Chile in its various contexts, to know the personal and family experiences of people with Chagas disease in the country. All this to build and analyze a corpus of experiences that allow to advance towards humanizing strategies that favor the diagnosis, timely and permanent treatment of affected people. The description of experiences related to Chagas disease has the potential to obtain recommendations to bring health services closer to more people, but with a personal, family and community emphasis that can progressively lead to better living conditions and social and health outcomes that will bring about improvements and benefits for those affected and their environment.

Methodology

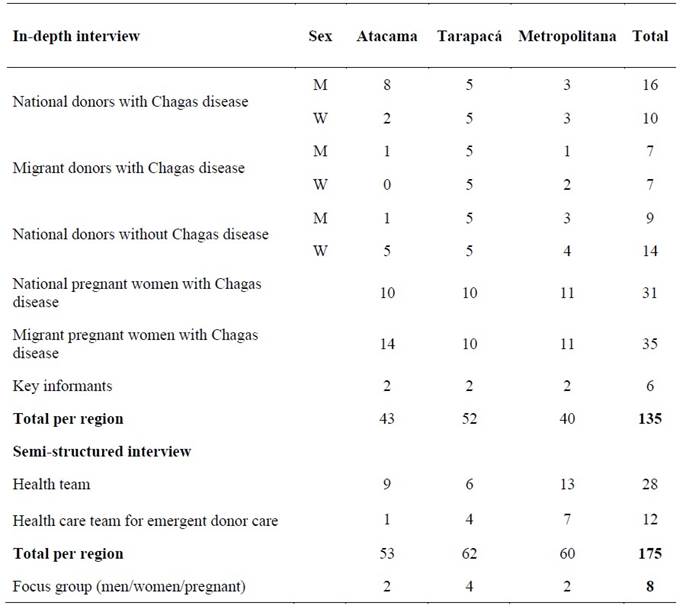

The methodology used in the study is applied qualitative. To analyze the experiences and meanings of Chagas disease in national and foreign women and men and in the treating health teams, which occur in the current diagnosis, care and follow-up of Chagas in the regions of Tarapacá, Atacama, and Metropolitan Chile between the years 2019 and 2021. These geographical areas were selected both for being of historical prevalence for Chagas disease 2 and with an important presence of migrants from endemic areas. A total of 175 people were included, among whom pregnant women were interviewed. This is a key group, since the technical standard indicates that all pregnant women should be screened. Nationals and migrants positive for T.cruzi, diagnosed in blood donations, were selected to receive information and treatment. Interviews were conducted with health teams and with health teams involved in blood donation, the latter having been incorporated, after having noted the low number of migrant donors with Chagas disease detected in each region. Interviews were conducted with key informants. On the other hand, focus groups were conducted considering people without Chagas disease who were treated at primary and secondary health care levels: men, women and pregnant women in each region. For this article, we will only consider the results related to pregnant women and donors (see Table 1).

The techniques used to collect information were in-depth interviews, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups. The first was developed using open-ended questions to identify emerging issues. In the second, a series of questions were used to contrast the responses of the health teams. For the focus groups, a guideline of questions was used, these instances were constituted with pregnant participants attended in primary health care (PHC), also with women and men attended in PHC, in both cases without Chagas. The research was initiated pre-pandemic and closed during the pandemic, being this process particularly complex. The result of the application of the techniques allowed the creation of an abundant textual corpus from the transcriptions of the interviews and groups.

The fieldwork was carried out by a methodological manager for each region, initially in person and then telematically. The management of contacts was facilitated by the treating health teams. Field work was managed in each region. A team of assistants was trained and supervised to support the interview work, and they were responsible for transcribing the material. The initial contact with the people affected was made by the health teams treating them, in order to contextualize and invite them to participate in the study. Then, the project research team framed the study, explained, and gave informed consent to the participants. It should be noted that not all the people contacted by the health teams agreed to join the process.

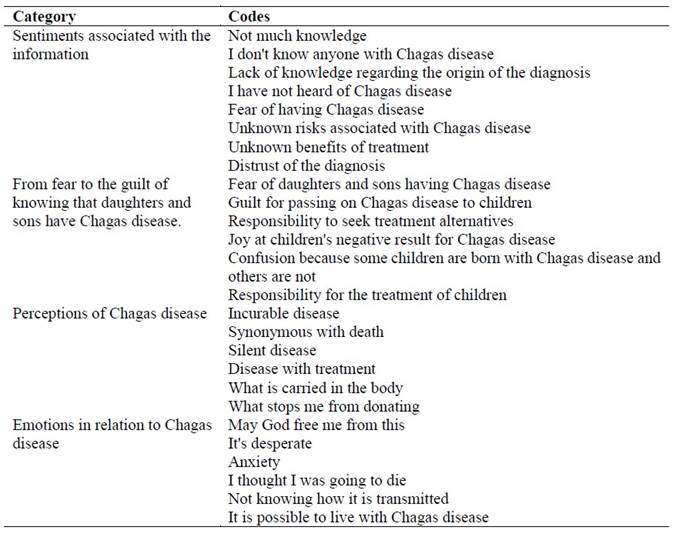

The analysis of the focal and global information was guided by the proposal of constant comparison within the framework of Grounded Social Theory (GST). 30,31 In this context, it was initially coded and analyzed in an open way, which was derived, in successive and recursive stages, towards axial coding through a series of relationships between codes (Table 2).

The analytical coding process was initially developed in parallel by the research team, based on the construction of codes associated with the specific objectives and their categories, on a selection of interviews, after which they proceeded to identify emerging codes, i.e. those that were not previously considered and that became evident in the process. The coding was subjected to discussion, and the codes and their meanings were unified to create a codebook. The code book was used to be applied to all the interviews and focus groups conducted, organizing this analysis in relation to the subjects: pregnant women, donors, health teams. A process of open coding (in vivo) of the interviews was carried out, the number of codes was expanded and adjusted, and they were grouped, based on more complex interpretations that allowed unifying the codes, establishing relationships and configuring categories related to the specific objectives.

We then proceeded to integrate the categories and their properties, to establish relationships that could be of an explanatory relational nature of causality, results, significance, relating each incident (axial coding) and subsequently relating previous analytical evidence to configure an explanatory model (substantive analysis).

For this article, we evidenced the open coding, and its relationships and preliminary groupings, only accounting for categories associated with the axes related to feelings and emotions. This analytical process was accompanied by the advice of an external team of expert researchers in GST, which favored a process of researcher triangulation. This support made possible a series of interpretative adjustments and the improvement of the analytical process.

Table 2: Selection of categories and codes where feelings and emotions related to Chagas disease are evidenced

Source: Own elaboration (2022)

A grouping of codes was constructed that favored the configuration of categories, based on the axes of gender, national origin, territory, and between the experiences of the participants in relation to gestation and donation and Chagas (explicit in the specific objectives). It should be noted that for the purposes of feelings and emotions the gender axes are more especially sensitive if we consider the condition of gestation, however, for the purposes of the differentiations of donation and territory these are coincidental.

Both the Nuremberg Code and the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association, and local provisions that regulate the conditions of access to research funds for access to people in care processes, placed the ethical considerations. The voluntary disposition and confidentiality of the participants' personal information (fictitious identities were assigned) was obtained by means of an informed consent, signed by the individuals.

The project, protocols and instruments were verified by the Ethics Committee of the Servicio Metropolitano Occidente de Salud de Santiago de Chile, and the project adaptations were ratified due to the pandemic context. The research team has access to the documents and transcripts through password.

Results

In this article we highlight the emotions associated with Chagas health care processes, mainly: Feelings related to information, fear, guilt, among others, perceptions and emotions around Chagas.

Sentiments associated with the information

The first family, Feelings associated with information, was made up of codes that show the participants' previous knowledge about Chagas disease, the means they had to obtain information and the evaluation of the quality of the information. These codes show that people received little information about the disease.

The results of this first category made it possible to observe that most people indicated that they had not previously heard about Chagas disease and had no information prior to diagnosis. A Chilean woman in a highly endemic area reported a lack of information and the need for it:

Yes, because of the concern, because obviously one starts with a disease that there is not much knowledge, what is a little bit within reach is the internet. And on the internet obviously you know you can find everything, and if you don't know how to channel that information well it can be a bit overwhelming (Chilean woman with Chagas disease, Atacama).

The accounts also refer to the formats and means through which it is necessary to receive information. For the people interviewed, the knowledge of peers and the relationship with peers on the issue is highly valued, as well as clear communication. In the words of a Chilean man:

With monitors, with people who go out to inform the parties, where this disease occurs, I think they should be aware of having trained people who have to do this work (Chilean man with Chagas disease, Tarapacá).

It is especially relevant that T.cruzi carriers indicated that they did not know anyone else with the disease. A code linked to the handling of information was "fear due to lack of information", the evidence of fear due to lack of information on Chagas disease was especially noticeable in the discourse of the people interviewed from the Metropolitan Region and mainly Chilean and Argentinean.

I have no idea, of course, for example, I can continue my normal life, but I do not know what risks I am taking, but (...), if I were in a treatment, I would like to know what benefits I will have, will I get rid of this disease or will I live until I die, maybe I will die from this disease and because I did not do a treatment I did not prolong my life any longer (Chilean man with Chagas disease, Metropolitan Region).

From the above words, not only fear is evident, but also the guilt associated with the actions and their consequences.

In this line, blood donors agree in indicating that the diagnosis of Chagas disease is associated with anguish, strangeness, concern and fear, among other feelings, which is produced because this diagnosis is communicated in a context in which people are informed of an infection that they do not know they have. People coincide in showing surprise at the diagnosis and also state that they are suspicious of it, because they feel healthy and not sick. In the following account, the explanations about the manifestation of the disease contrast with what the interviewee experiences, which makes her doubt the veracity of the diagnosis:

I always thought that maybe they had made a mistake in the result, I would like to take that test again to see if I really have it. I have a kind of doubt. I don't know (...), because (...) I don't know, because of what I have been told, that I could have intestinal problems, which I don't have, and when swallowing it also seems that it was something like that, of the esophagus, I don't have either, only if I suddenly have a pain here in the chest, yes, because when I force the muscles go “crac”, I always get it (Chilean woman donor with Chagas disease, Metropolitan Region).

Knowing that daughters and sons have Chagas disease: guilt and fear

This second category mainly considered the statements that testify to the relationship between Chagas disease and the diagnosis of the children. The reports coincide in affirming that the children “do not have the disease”. However, it is significant that the people interviewed agree in indicating their willingness to undergo treatment, especially those who have children. Among the emotions described especially by the women, guilt stands out, associated with the possibility that their offspring would have been diagnosed positive for the parasite. In this sense, having a child with a negative diagnosis is a relief:

It was already, it already happened, that is, for my happiness, because my daughter was negative, but there began the issue of anxiety to start treatment, because (I) was asymptomatic, then better before, because that decreases the risk of the manifestation of the disease (Chilean woman with Chagas, Atacama).

For women, guilt is related to the possibility of passing on T.cruzi to their children, as the following accounts illustrate:

I would have felt, well, actually, a little bad, because, well, even if it was not my fault, wasn't it, that I would have had Chagas, and spread it to them, but still I would have felt a little (...) I would have felt bad (Bolivian woman with Chagas disease).

It complicated me a lot, how I was going to tell my parents, not because it was something totally serious. Well, now I also know that I am a mother, any illness of the children is like it throws you off balance (Chilean woman with Chagas disease, Atacama).

When comparing the regional geographic distribution of the participants, i.e., when considering the axis of the territory, it is interesting to note the absence of significant differences in the feeling of guilt. However, it is possible to point out that guilt is mentioned and, in the face of a positive diagnosis, the possibility of seeking means to treat the disease. These narratives gain more strength among migrant women of Bolivian nationality, with sons and daughters, the responsibility for treatment is reinforced:

I have to be cured, I am young, I am not old, if or if I have to get cured. My daughters will also miss me one day, they will tell me: “my mother is not alive”, “I need my mother”, they will also ask their father: “Where is my mother, why didn't you cure her, now we need my mother”, they will tell him too (Bolivian woman with Chagas disease).

I would feel guilty, because if, I don't know, maybe if I had known before, I would do a treatment, if I wanted to have a child, so I wouldn't transmit the disease or something like that (Bolivian woman with Chagas disease).

Perceptions of the disease

The third grouping of codes was called Perceptions of Chagas disease. In this, a series of codes are linked to significant associations linked to the belief that “Chagas is an incurable disease, synonymous with death”, then, that it is “a silent disease that has treatment”, that it is “asymptomatic” and that it is “from the north of Chile”. This category is subgrouped between codes, on the one hand, that express negative and alarming associations, such as Chagas incurable, very dangerous, synonymous with death and, on the other hand, as a silent disease, asymptomatic, “but not so serious”. In this last subgroup are the participants who refer that it is a “treatable” disease, “that does not prevent having children”, “that can be carried in the body”, “that allows one to live peacefully”, “that cannot be seen”. Interestingly, a third subgroup of codes was identified in the family Chagas disease as (...), which shows a “positive perspective on the disease”, in which there is evidence of a view of Chagas disease as a “treatable disease” and “that does not disturb sleep”, especially when compared with other diseases.

For those who have discovered Chagas through donation, this diagnosis constitutes an impediment to continue donating blood, which results in a feeling of frustration because it implies a limitation that also extends to the family. As observed in the words of a male donor, he states the surprise of the diagnosis, has an impact on the family:

I came out (positive) with Chagas, I told my brothers, they took the test and they both came out positive, so they cannot donate blood (Chilean male donor with Chagas, Atacama).

Emotions in relation to Chagas disease

The last category recognizes the most significant emotions associated with the disease. In this category, mainly concern, grief, depression, fear, surprise, anger, anxiety about the diagnosis and treatment were identified. These emotions constitute responses to the lack of information, to the reproduction of barriers.

Discomfort also translates into emotions such as hopelessness. In the words of a Chilean woman, a divine solution is expected, real possibilities are left out. The consequences of Chagas disease are experienced as complex:

I think I would start asking God to get rid of that bug, I don't know how(...), because for me it is something desperate, just the same (...) I think about tomorrow (...), if one of my siblings, because we are 11 siblings and most of my siblings suffer from the guatita (digestive system), one has already died (...), he died very young, at the age of 47 and now one of my siblings has had heart surgery, they put a pacemaker, a little machine (Chilean woman with Chagas disease, Atacama).

In the words of another woman, the relationship between the lack of information, the representation of Chagas associated with death, and emotions such as anxiety, anger, product of the lack of prevention related to transmission routes is evident.

Then he contacted me, the technologist, contacted me with the doctor and I talked to her on the phone and, she kind of lowered my anxiety a little, as well as I thought I was going to die and that I was going to almost have an infarction or that I was going to start with arrhythmia at that very minute and they told me already, it was another Friday on top of that. On Monday we have to prick (blood tests) your (older) daughter, we have to prick your mother and depending on her results we will see what to do, if your daughter is positive we have to treat her, for me that was the worst thing, the worst, the worst, the worst. To think that I have something that I don't know how old it is, that I don't know how it is, that I don't know how it is transmitted, not even through sexual relations that you can say like HIV, that I got it because I didn't take care of myself, because I didn't use a condom, no, here it was like it never depended on me, so it was like a rage, a shame, but more than anything a rage that you don't know who to feel it against because finally with the other question if you didn't take care of yourself you feel rage against yourself (Chilean woman with Chagas disease, Metropolitan Region).

In this set of experiences of the subgroup of codes that denote fear of death, fear of contagion of sons or daughters and uncertainty and concern about the possibility that the disease could affect relatives, stand out in this set of experiences. It is worth noting in these accounts the naturalization of the diagnosis. This is evidenced in statements such as "you have to die of something", which can be interpreted as the need to accept the diagnosis and accept the consequences of this. The diagnosis is dissociated from consequences or physical discomfort. In this sense, not having symptoms related to the disease has an impact on the perception of a lower risk of the disease.

Not having evident consequences of the development of a disease is experienced with less anguish. It is a relief, it does not affect daily life, as it happens with other diagnoses.

Let a doctor explain it to you, I think, but yes, afterwards I would talk, 'well, be calm', if it is that, and it is not cancer, or AIDS, which is terrible, or some terrible disease; for me Chagas is something super (...), calm (...), it is just there, my children came out well, it was not activated, as far as I know, it was not activated and that's fine, if that is all it is (Chilean woman with Chagas disease, Tarapacá).

Living with Chagas is the same as living without Chagas, I think, because it does not affect me in any way, your daily life, yes, I think that hypothyroidism affects me more, when I am unbalanced, dead sleepy, tired, but Chagas until today, and I am very grateful for it, for me it does not have any difficulty, that is, we associate it with constipation problems in my family, which can be, that the colon feels (...), besides, we are all a bit nervous, we are all a bit nervous, we are all very nervous, we are all a bit nervous. ), besides, we are all nervous people, so it is like (...), we do not know if it is a nervous colon or Chagas colon (laughs) (Chilean woman with Chagas, Tarapacá).

Living with Chagas, without feeling sick, is a challenge for people and for health teams.

Discussion

The results of the study allow us to highlight emotions related to fear, sadness, and hopelessness, which are closely associated to the information given to people. These feelings are linked to the experiences of illness or death of family members. Guilt, anger, and responsibility are observed especially in women, because of the possibility of passing on the parasite to offspring. Emotions such as joy and gratitude emerge in the face of negative T.cruzi results.

This study coincides with Ventura García et al., 19 Ventura García, 20 and Sanmartino et al., 22 especially in the link established between the lack of information about Chagas disease and the feeling of fear of diagnosis by people, especially blood donors and pregnant women. Sadness and feeling bad are recurrent feelings in the testimonies of women and men who received little information during diagnosis. Feelings and emotions such as anguish, surprise, strangeness and worry, and depressive symptomatology, 24 are observed in donors who are unaware of the routes of transmission of the infection.

It is important to emphasize that negative emotions and feelings are also present in the experiences related to children. Coincidentally with Sanmartino, 22 the research identified that guilt is a significant concept for women diagnosed during pregnancy. Joy, as a feeling, emerges when observing a negative result in the children, which differs from guilt and fear in cases in which the result is positive. However, the lack of or little information is again positioned as a relevant aspect in the testimonies of the participants who suspect they have the disease, whether they are blood donors or pregnant women or women of childbearing age; the latter is also observed by Van et al. 3

Most of the feelings and emotions with a negative effect on people are related to the positive diagnosis in pregnant women and blood donors in Chile, due to the lack of information, or to the perceptions of Chagas disease, which translate into emotions such as fear, sadness and guilt predominant in the stories. It should be noted that the lack of knowledge and scarce information regarding the forms of contagion is linked to the fear of death, the belief that this is a disease with no solution or treatment, which coincides with other studies. 21,25

Clearly, feelings about Chagas disease have a negative impact on timely care and adherence to treatment. Pregnant women in particular feel sad, discouraged and fearful as Chagas disease is seen as a disease without a cure and is directly related to death.

Addressing people's feelings and emotions during diagnosis has an impact on the success of the implementation of Chagas disease prevention and care policies in Chile. 24 It is important to note that feelings such as fear and silence go hand in hand with experiences of stigmatization, as pointed out by Castaldo et al. 27

Timely and clear information to reduce feelings and emotions that hinder adherence to treatment and health follow-up, as Acosta-Romo et al. 32 agree, is essential to humanize care and health care.

Final considerations

The study reaffirms the findings of predecessors research conducted in various countries. There is coincidence in underlining the relevance of making visible the feelings of the people affected by the disease and of the population in general. The feelings expressed speak of the impact of the positive diagnosis and its significance. They show, through their expressions, the discomfort it produces and the complex relationships that occur within families, and in the interaction with the teams and with societies in general. It highlights the place of information and communication about Chagas disease, its significant weight in processes of humanization of health care. Focusing on emotions and feelings helps to ponder the gaps or lack of information that affects people.

Understanding the family, social and community context of people with Chagas disease is fundamental in the development of humanizing strategies, appropriate to the particularities of the population. Communication between the system and people is a determining factor in health processes.

Similarly, it is recommended that these contents be included in the improvement of the implementation of Technical Standard N.º 162, and in its revision. And actions to increase information, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up processes. Likewise, education and training strategies for health personnel would increase feelings of proximity. Empathy is closely related to good practices in health and in Chagas disease.

Understanding the origin of feelings related to diagnosis, information, and significance of this problem, and undoubtedly, the improvement of indicators associated with screening, adherence to treatment and follow-up, not only in the Chilean context, are necessary.

The results and their analysis show the importance of considering the interpretations and intersubjective scopes in a complex health problem such as Chagas disease, advancing in the comprehensive description of feelings, favors illuminating the implementation of the national plan and the technical standard in relation to this specific population. Undoubtedly, improving strategies to inform about the disease, communicating the results of the diagnosis, and about the alternatives associated with health controls and treatment, are fundamental aspects, and contribute to reduce fears, fears of death, feelings related to the implications of the disease, considering feelings as indicators that favor feelings for the positive impact of screening and its universalization.

Direct contact, containment based on active listening and the development of empathy on the part of the health teams are fundamental to stimulate a dignified treatment, based on the axis of health rights. It is essential to advance in social organization, associativism, which also allows to contain, accompany, and legitimize needs in the context of a highly unknown infection and with an important stigma that is reproduced based on ignorance.

Transforming feelings of sadness, disappointment, strangeness, discomfort, concern, guilt, among others, is the task of the health teams, sectoral technicians, and health policy guidelines; we should consider these feelings as evidence of the deficit in the implementation of the policy. Clearly, the enunciation of feelings of tranquility, trust, empathy, respect, will be signs of efficient and effective progress in information, communication, and education about Chagas disease.

Undoubtedly, the transformation of the feeling about Chagas disease must summon the whole community and validate the support of informed and organized peers. Clear, inclusive information will favor interactions without stigmas or mistaken preconceptions. The opportunity that the research opens for us through the understanding of people's feelings allows us to advance in the recognition of others, their needs, differences, social, cultural and territorial contexts. It allows us to build a dialogic, empathic relationship, from an ethics of recognition, of dignified and humanizing treatment, on the recognition of health as a right.

REFERENCES

1. Echeverría L, Marcus R, Novick G, Sosa-Estani S, Ralston K, Zaidel E, et al. WHF IASC Roadmap on Chagas Disease. Global Heart (Internet). 2020 (citado Feb 2022);15(1):26. DOI: 10.5334/gh.484 [ Links ]

2. Avaria A, Ventura L, Sanmartino M, Van der C. Population movements, borders, and Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2022 Jul 8;117:e210151. [ Links ]

3. Van Wijk R, Van Selm L, Barbosa MC, Van Brakel WH, Waltz M, Philipp Ruchner K. Psychosocial burden of neglected tropical diseases in eastern Colombia: an explorative qualitative study in persons affected by leprosy, cutaneous leishmaniasis and Chagas disease. Global Mental Health (Internet). 2021 (Citado Feb 2022);8:e21. DOI: 10.1017/gmh.2021.18 [ Links ]

4. Dibene B, Ceccarelli S, Marti G, Sanmartino M. Chagas y comunicación en salud. Experiencias con foco en la participación comunitaria y el desafío de superar estereotipos y discursos hegemónicos. Actas de Periodismo y Comunicación (Internet). 2020 (citado Feb 2022);6(2). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/124116 [ Links ]

5. Organización Mundial de la Salud. La enfermedad de Chagas (tripanosomiasis americana) (Internet). 2021 (citado Mar 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis)#:~:text=Se%20calcula%20que%20en%20el,tiempo%20de%20produc irse%20la%20infecci%C3%B3n [ Links ]

6. Jimeno I, Mendoza N, Zapana F, De la Torre L, Torrico F, Lozano D. Social determinants in the access to health care for Chagas disease: A qualitative research on family life in the “Valle Alto” of Cochabamba. PLoS ONE (Internet). 2021 (citado Mar 2022);16(8): e0255226. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255226 [ Links ]

7. Rey-León J. La justicia social en salud y su relación con la enfermedad de Chagas. Rev Cubana Salud Pública (Internet). 2020 (citado Mar 2022);46(4):e1264. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.revsaludpublica.sld.cu/index.php/spu/article/view/1264 [ Links ]

8. Gorla D, Xiao Z, Diotaiuti L, Thi Khoa P, Waleck E, Cássia R, et al. Different profiles and epidemiological scenarios: past, present and future. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz (Internet). 2021 (citado Mar 2022);117. DOI: 10.1590/0074-02760200409 [ Links ]

9. Galáz C, Avaria A, Silva C. Avances y Limitaciones en la Investigación sobre Factores Sociales Relativos a la Migración y Chagas. Humanidades Med. (Internet). 2021 (citado Feb 2022);21(2):597-614. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://humanidadesmedicas.sld.cu/index.php/hm/article/view/1835 [ Links ]

10. Sanmartino M, Forsyth CJ, Avaria A, Velarde-Rodriguez M, Gómez i Prat J, Albajar-Viñas P. The Multidimensional comprehension of Chagas disease. Contributions, approaches, challenges and opportunities from and beyond the Information, Education and Communication field. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2021;116:e200460. DOI: 10.1590/0074-02760200460 [ Links ]

11. Subsecretaría de Salud Pública de Chile. Minuta por Conmemoración del Día Internacional de las Personas Afectadas por Enfermedad de Chagas. (Internet). 2021 (citado Abr 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Minuta-Dia-Mundial-de-Enfermedad-de-Chagas.pdf [ Links ]

12. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Informe de Vigilancia Integrada Anual Enfermedad de Chagas (Internet). 2022 (citado Abr 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2022.03.14_INFORME-ENFERMEDAD-DE-CHAGAS.pdf [ Links ]

13. Subsecretaría de Salud Pública de Chile. Informe Encuesta Nacional de Salud. (Internet). 2016-2017 (citado Abr 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://epi.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2022.01.03_Informe-Enfermedad-de-Chagas.pdf [ Links ]

14. Ayala S, Alvarado S, Cáceres D, Zulantay I, Canals M. Estimando el efecto del cambio climático sobre el riesgo de la enfermedad de Chagas en Chile por medio del número reproductivo. Rev. méd. Chile (Internet). 2019 (citado Abr 2022);147(6):683-692. DOI: 10.4067/S0034-98872019000600683 [ Links ]

15. Reyes R, Yohannessen K, Ayala S, Canals M. Estimaciones de la distribución espacial del riesgo relativo de mortalidad por las principales zoonosis en Chile: enfermedad de Chagas, hidatidosis, síndrome cardiopulmonar por hantavirus y leptospirosis. Rev. chil. infectol. (Internet). 2019 (citado Abr 2022);36(5):599-606. DOI: 10.4067/S0716-10182019000500599 [ Links ]

16. Denegri M, Oyarce A, Larraguibel P, Ramírez I, Rivas E, Arellano G. Cribado y transmisión congénita de la enfermedad de Chagas en población usuaria del Hospital Dr. Félix Bulnes Cerda y Atención Primaria de Salud del Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Occidente de Santiago, Chile. Rev. chil. infectol. (Internet). 2020 (citado Mar 2022); 37(2):129-137. DOI: 10.4067/s0716-10182020000200129 [ Links ]

17. Papiol G, Norell M, Abades M. Análisis del concepto de serenidad en relación con el apoyo psicológico y emocional del paciente crónico. Gerokomos (Internet). 2020 (citado Jul 2022);31(2):86-91. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1134-928X2020000200006&lng=es [ Links ]

18. Carcausto W, Morales J, Calisaya-Valles D. Abordaje fenomenológico social acerca de la vida cotidiana de las personas con tuberculosis. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral (Internet). 2020 (citado Jul 2022);36(4). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.revmgi.sld.cu/index.php/mgi/article/view/1126 [ Links ]

19. Ventura-Garcia L, Muela-Ribera J, Martínez-Hernáez A. Chagas, Risk and Health Seeking among Bolivian Women in Catalonia. Medical Anthropology: Cross Cultural Studies in Health and Illness (Internet). 2021 (citado Abr 2022);40(6):541-556. DOI: 10.1080/01459740.2020.1718125 [ Links ]

20. Ventura-Garcia L. “Tú me dirás: yo, ¿de cuáles soy?”: la práctica clínica del Chagas como riesgo latente. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva (Internet). 2022 (citado Abr 2022);27(3)871-879. DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232022273.33482020 [ Links ]

21. Avaria A, Goméz J. “Si tengo Chagas es mejor que me muera”. El desafío de incorporar una aproximación sociocultural a la atención de personas afectadas por enfermedad de Chagas. Rev Enf Emerg. 2008;10(1):40-5. [ Links ]

22. Sanmartino M, Avaria A, Gómez Prat J, Parada MC, Albajar-Viñas P. Do not be afraid of us: Chagas disease as explained by people affected by it. Interface: Communication, Health, Education (Internet). 2015 (citado Feb 2022);19(55). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://repositorio.uautonoma.cl/handle/20.500.12728/6186 [ Links ]

23. Ozaki Y, Guariento M, De Almeida E. Quality of life and depressive symptoms in Chagas disease patients. Qual Life Res 20 (Internet). 2011 (citado Sep 2022);20(1):133-138. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-010-9726-1 PMID: 21046258 [ Links ]

24. Forsyth C, Hernandez S, Flores C, Roman M, Nieto J, Marquez G, et al. (2021). You Don't Have a Normal Life: Coping with Chagas Disease in Los Angeles, California. Medical Anthropology (Internet). 2021;40(6):525-540. DOI: 10.1080/01459740.2021.1894559 [ Links ]

25. Asociación Civil Hablemos de Chagas. Comunicación y Chagas, bases para un diálogo urgente (Internet). 2021 (citado Abr 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://libros.unlp.edu.ar/index.php/unlp/catalog/book/1756 [ Links ]

26. Alves de Oliveira W, Gómez J, Albajar-Viñas P, Carrazzone C, Petraglia S, Dehousse A, et al. How people affected by Chagas disease have struggled with their negligence: history, associative movement and World Chagas Disease Day. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz (Internet). 2022 (citado Abr 2022);117. DOI: 10.1590/0074-02760220066 [ Links ]

27. Castaldo M, Cavani A, Segneri MC, Costanzo G, Mirisola C, Marrone R. Anthropological study on Chagas Disease: Sociocultural construction of illness and embodiment of health barriers in Bolivian migrants in Rome, Italy. PLoS One (Internet). 2020 (citado Sep 2022). PMID: 33064748 PMCID: PMC7567347 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240831 [ Links ]

28. Gómez J., Peremiquel-Trillas P., Claveria I., Caro J., Choque E., De Los Santos JJ., Sulleiro E., Ouaarab H., Albajar P., Ascaso C. Comparative evaluation of community interventions for the immigrant population of Latin American origin at risk for Chagas disease in the city of Barcelona. PLoS One (Internet). 2020. (Citado Sep 2022); 15(10):e024083. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32663211/ [ Links ]

29. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Manual de procedimiento para la atención de pacientes con enfermedad de Chagas (Internet). 2017 (citado Mar 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wrdprss_minsal/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2018.01.18_ENFERMEDAD-DE-CHAGAS-2017.pdf [ Links ]

30. Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [ Links ]

31. Strauss A, Corbin J. Bases de la investigación científica. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Colombia: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia; 2002. [ Links ]

32. Acosta-Romo MF, Cabrera-Bravo N, Basante-Castro Y, Jurado D. Sentimientos que experimentan los padres en el difícil camino de la hospitalización de sus hijos prematuros. Un aporte al cuidado humanizado. Rev Univ. Salud. 2017;19(1):17-25. [ Links ]

Funding and acknowledgements: This article was sponsored by the Fondo Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo en Salud, FONIS SA18I0056 "Chagas challenges for today's Chile: diversity, migration, territory and access to rights. A qualitative approach to the dynamics of attention to Chagas disease in the Tarapacá, Atacama and Metropolitan Regions", project executed through the Universidad Autónoma de Chile, under the direction of Dr. Andrea Avaria. We thank the research team and assistants who made the success of the project possible. We thank the National Responsible for Chagas Disease Prevention and Control. Jorge Valdebenito, of the Department of Communicable Diseases, Division of Disease Prevention and Control, Ministry of Health, we thank the regional health teams and the women and men with Chagas disease who were interviewed.

Note: This article is part of the dossier "Qualitative methods for social transformation, interculturality and resilience", which brings together papers produced in the context of the VI Summer School on Qualitative Methodologies for Social Transformation in the Border Zone, held on January 13 and 14, 2022 and coordinated by the Escuela de Psicología y Filosofía in conjunction with the Departamento de Ciencias Sociales de Universidad de Tarapacá, Sede Iquique, Chile.

How to cite: Garrido Cabezas N, Avaria A. Feelings and Emotions Present in the Experiences of Pregnant Women and Donors with Chagas Disease in Chile. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2022;11(2):e2901. DOI: 10.22235/ech.v11i2.2901

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. N. G. C. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; A. A. ha contribuido in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: May 11, 2022; Accepted: October 03, 2022

text in

text in