Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.11 no.2 Montevideo Dec. 2022 Epub Dec 01, 2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v11i2.2900

Dossier: Qualitative methods for social transformation | Original Articles

What is the Story Behind the Images? Biography and Illustration in the Background of a Trajectory Study

1 Universidad de Chile, Chile, grubilar@uchile.cl

Objective:

To analyze the links between biographical approach and illustration, from an interpretative paradigm and following the theoretical-methodological guidelines of the biographical-narrative approach.

Methodology:

It includes the interpretation of narratives constructed by the researchers, which are captured in an image or graphic illustration that is offered to those who participate in the study for their approval, followed by a theoretical discussion of the place of the image in the current context. The article describes the methodological process of producing these images, including an analysis of two experiences.

Result:

The analyzed experiences serve as background for the final product of this research, which reconstructs research trajectories and transitions of exponents of a discipline. The methodological process of production of these images is discussed, hence, this proposal of biographical illustrations is subsequently translated into a book-album that includes sixteen testimonies of social workers.

Conclusion:

It is highlighted the importance of developing a reflexive process on qualitative research practices and backroom analysis of research results, including science dissemination activities in non-academic formats.

Keywords: trajectories; personal narratives; biographical approach; information dissemination; knowledge transfer

Objetivo:

Analizar los vínculos entre enfoque biográfico e ilustración, desde un paradigma interpretativo y siguiendo las directrices teórico-metodológicas del enfoque biográfico-narrativo.

Metodología:

Se incluye la interpretación de narrativas construidas por las y los investigadores, que se plasman en una imagen o ilustración gráfica que es ofrecida a quienes participan del estudio para su aprobación, seguido de una discusión teórica del lugar de la imagen en el contexto actual. El artículo describe el proceso metodológico de producción de estas imágenes, incluyendo un análisis de dos experiencias.

Resultado:

Las experiencias analizadas sirven de antecedente para el producto final de esta investigación, que reconstruye trayectorias y transiciones investigativas de exponentes de una disciplina. Se discute el proceso metodológico de producción de estas imágenes, de allí que esta propuesta de ilustraciones biográficas se plasme posteriormente en un libro-álbum que incluye dieciséis testimonios de trabajadores sociales.

Conclusión:

Se destaca la importancia de desarrollar un proceso reflexivo sobre las prácticas de investigación cualitativa y análisis de trastienda de los resultados de las investigaciones, incluyendo actividades de divulgación de la ciencia en formatos no académicos.

Palabras claves: trayectorias; narrativas personales; enfoque biográfico; divulgación de información; transferencia de conocimiento

Objetivo:

Analisar as ligações entre a abordagem biográfica e a ilustração, a partir de um paradigma interpretativo e seguindo as diretrizes teórico-metodológicas da abordagem biógico-narrativa.

Metodologia:

Inclui a interpretação de narrativas construídas pelos pesquisadores, que são capturadas em uma imagem ou ilustração gráfica que é oferecida àqueles que participam do estudo para sua aprovação, seguida de uma discussão teórica sobre o lugar da imagem no contexto atual. O artigo descreve o processo metodológico de produção dessas imagens, incluindo uma análise de duas experiências.

Resultado:

As experiências analisadas servem de base para o produto final desta pesquisa, que reconstrói trajetórias de pesquisa e transições de expoentes de uma disciplina. O processo metodológico de produção destas imagens é discutido, razão pela qual esta proposta de ilustrações biográficas é posteriormente traduzida em um livro-álbum que inclui dezesseis testemunhos de assistentes sociais.

Conclusão:

Destaca-se a importância de desenvolver um processo reflexivo de práticas de pesquisa qualitativa e análise dos resultados da pesquisa nos bastidores, incluindo atividades de divulgação científica em formatos não acadêmicos.

Palavras-chave: trajetórias; narrativas pessoais; abordagem biográfica; disseminação da ciência; transferência de conhecimento.

Introduction

This article analyzes and discusses the possibilities afforded by illustration for the dissemination of the results of studies conducted using qualitative approaches. We acknowledge the ambivalent power of images 1-2 while at the same time addressing the possibilities and limitations of their use in academic contexts to generate interpretative frameworks and new ways of seeing knowledge construction in a specific field -in this case, social work. This theoretical-methodological reflection emerged in the context of a set of illustrations produced in the last few years, inspired by materials yielded by qualitative studies. These efforts later resulted in a workshop entitled “Biography and Illustration”, presented at the VI Summer School on Qualitative Methodologies for Social Transformation in the Border Zone. The author of this article took part in this project since its inception 3 and, on this specific occasion, the speakers presented the results of a longitudinal qualitative study consisting in a diachronic analysis of the research conducted thus far, examining its specific features and contributions to social work while also trying out new ways to disseminate and visibilize the work carried out.

Therefore, this study is part of the sociology of science, longitudinal qualitative studies, and trajectory studies, since it sought to generate a longitudinal reconstruction of the research trajectories of people who have helped to create knowledge in a specific discipline. Specifically, the study explores the characteristics and contexts of the research generated, the ways in which it is carried out, and its main contributions to knowledge production.

Longitudinal qualitative studies, especially clinical trajectory studies, have an interesting history in the health care field. 4-5 A brief compilation of this line of research can be found in Tuthill et al., 6 which presents a detailed analysis of other studies with this type of design. In social research, they are used as a device for following up processes and subjects over time 7 especially in life cycle studies and in the tradition of biographically focused trajectory studies. 8-10

Specifically, this article analyzes some qualitative research experiences whose results are partially presented by means of illustrations or images that summarize aspects or fragments of the life histories of the research subjects. Our article emphasizes the methods of production and interpretation of images produced within the context of research dissemination, offering to the public a set of illustrations aimed at summarizing or integrating interviews and research products. These elements are offered to audiences as an opportunity for them to carry out an open interpretation of a life history or fragments of it; for instance, the testimonies included in this study. 11

In this context, our study engages in a conversation with other narrative products such as those developed by Obrist 12) in The Interview Project and autoethnographic creations by visual artists like Voces que cuentan (Voices that Narrate) 13 y Maldita tesis (Damn Thesis),14 two pieces that informed the definitions adopted in a book presenting the results of this research project. In the following sections, we present the theoretical-methodological decisions that guided our work.

Methodology

This study was conducted according to the interpretative paradigm, following the theoretical-methodological guidelines of the biographical-interpretative approach (3, 7, 9) with a longitudinal qualitative design aimed at following up subjects over time 8 through a set of biographical interviews. 15-16 We conducted it similarly to labor trajectory studies in a wide range of fields, including French bakers, 17 Colombian and German factory workers, 18 Argentine YPF workers, 19 polo workers 20 and plastic artists. 11

The author of this article held interviews with Chilean social workers at multiple time periods within the context of different research projects. Therefore, the study was conducted over several years, with the participants being interviewed on more than one occasion. All interviewees signed an ethical consent form to participate in the study, which followed the protocols for research involving human beings.

This study adopted a longitudinal qualitative design comprising interviews repeated every 5-6 years, which made it possible to establish a sequence of over 20 participants with sessions lasting for more than one decade. The participants in this longitudinal study were selected through snowball (purposive) sampling, considering disciplinary relevance, doctoral qualifications, geographical location, and generation (age/year of graduation from their university program). For some people, this interview process started in 2008, which has made it possible to complete up to three meetings, while others have taken part in interview sessions on two occasions, in 2014 and 2019 or 2020. As of this writing, a cycle of repeated interviews is being conducted with subjects who were interviewed in 2012 and re-interviewed in 2022; therefore, their testimonies are not included in this analysis.

The criterion for determining the number of participants in this project followed what Bertaux 8 refers to as “index paradigm”, which is aimed at producing an analysis that reveals irregularities rather than recurrent events. In this regard, we chose to collect several narratives that would enable us to conduct an in-depth study while at the same time making available several experiences that would guarantee some degree of diversity in the trajectories studied.

The conversations held in each meeting followed a flexible script, typical of reflective interviews, which encourages the interviewee to engage in a critical analysis of their own research experience and the framework that provides it with meaning.(21, 22)

Our analysis of research trajectories belongs to a line of research that pays close attention to researchers’ reflections on their own work. 23 Therefore, it is essential to return part of the materials produced to their protagonists. Initially 24 this restitution was conducted individually, by means of a written product entitled “testimony”: a first-person text that integrated the contents of each meeting (interview) and their transitions over time. This prompted the first interpretation of the participants' trajectories through a written testimony.9

The materials of the biographical testimonies were compiled over time, resulting in text files written in the first person and covering thematic axes that reflect several watershed moments in the participants' trajectory. This material, considered a research byproduct, is not of a public nature; rather, it is given back to the participants as part of the research process and offered in return for the time that they devoted through their involvement. It is an aesthetic product with hyperlinks to various points of their digital biography, assembled so that their conversations over time are merged into a single piece that combines into one paragraph a set of temporalities and views on the careers of the protagonists of this study.

Results

How to disseminate the results of biographical research? Two prior trials before reaching the definitions used in this study

How to present the material produced in biographical studies to a larger audience? What aspects of the participant's career/history should be highlighted? These were some of the questions that we have addressed in our debates and the subsequent methodological choices made in this study, whose results we also set out to disseminate across networks and events that promote research practices and contribute to disciplinary development.

Such events include not only scientific dissemination seminars, talks, and conferences, but also books, which are defined or offered as the products of a study and enable us to answer the question “what do we do with our research”, beyond writing articles for academic journals. 24

Our team has the practice of participating in science outreach seminars, initiatives aimed at a wider audience and not limited to academic spaces, where the audience is usually composed of young people and adolescents in school or the public in general interested in the research work in social sciences. We also accept invitations to give workshops or methodological seminars, or to comment on or present the research work of other teams, as in the VI Summer School on Qualitative Methodologies for Social Transformation in the Border Zone.

In this context, in November 2020 dos, two researchers invited us to present a book compiling the stories of Social Work undergraduates and professional social workers who had been detained and then made to disappear during the dictatorship. 25 This book contains 16 micro biographies produced by holding interviews with relatives, friends, and colleagues of 7 Social Work undergraduates and 9 professional social workers.26 It is worth noting that, from a methodological point of view, this study posed a challenge that enabled us to trial and put into practice -on the day of this book launch- an initial dissemination method that articulated biography and illustration.

On that occasion, we chose to represent and illustrate two narratives produced by social workers from different generations: a professional social worker and an undergraduate. To generate the illustrations, we pre-selected some fragments of their micro biographies which an illustrator interpreted to produce three depictions of their lives. Seeking to answer the question “what would they be doing today?”, we tried to articulate the biographical narration of these historiographies with the performative exercise of bringing their past lives into the present, two key elements of the biographical approach. 9

After presenting the main guidelines of the book, we read out loud the pre-selected fragments using a tone and timber that would match the contents of the text narrated; thus, we used two voices to differentiate the biographical representation of the professional from that of the young undergraduate. Book launch attendees included family members and friends of the people represented. For the sister of one of them, this performance was a highly valued political gesture of acknowledgment, which enabled others in the audience to understand the scope of their lives and the connection between the micro biography constructed by the book's authors and the illustration, offered as a second examination of this research effort.

Looking back, we can say that this was certainly a risky choice, since at that point we lacked adequate theoretical or conceptual examinations of this format that marries biography with illustration. Therefore, the conversations that followed this book launch, plus a later exercise, enabled us to cement this bond and make it meaningful, since the aesthetic experience was somehow captured in this initial opening act.

Below, we present one of the pre-selected fragments and the illustration generated upon the basis of this narrative (Figure 1).

Cecilia10 was “a very good student (…) she was brilliant, especially in the Sociology subject. As a third-year student, she became a methodology and research assistant. After she graduated, she continued to work in the research field”. 25

We followed the same procedure to generate the illustration of María Teresa Bustillos’11 micro biography, and to explore how the interviewees would visualize her today Figure 2:

“she'd be involved in some of the hot button issues nowadays, the problems of women, (…) in Sename12, (…) due to her profession, she'd be closely involved in these things”. (…) María Teresa would have liked to get involved in today's social movements, she'd go to demonstrations with us, like the No + AFP marches or those demanding quality education… 25

Later, we were asked to contribute to the methodological discussion process of a study involving biographical interviews with sexually dissident older adults in Argentina. On this occasion, the process comprised three training sessions that included an individual analysis of the interviews, a comparative analysis of the biographical materials produced, and the decisions made regarding the dissemination of their results. Some issues surrounding authorship and its ethical dilemmas are discussed in a recent article, 24 and thus not covered in this study; rather, we focus on how the products of this study were communicated and how the narratives included in the publication of this process were utilized. 27

The researchers co-produced a book that presents a first-person narrative of the stories of older adults who advocated for human rights, women's rights, and sexual dissidence. Again, two stories were selected for the book launch. They were constructed using interviews and some paragraphs were chosen to illustrate them, as a way of strengthening the hermeneutic nature of the analysis of the fragments.

The results of this second performative exercise were like those of the previous book launch, but with one major difference: some of their protagonists were in the same space-time that their images depicted. This meant that it was possible to get a first-hand impression of their views or the impact of this re-interpretative act, which was also actualizing to some extent as the illustration was either received or rejected by the author. Three illustrations per narrative were constructed, but only two are presented for illustrative purposes.

The following excerpt from María Belén Correa’s13 testimony was the inspiration for the illustration (Figure 3):

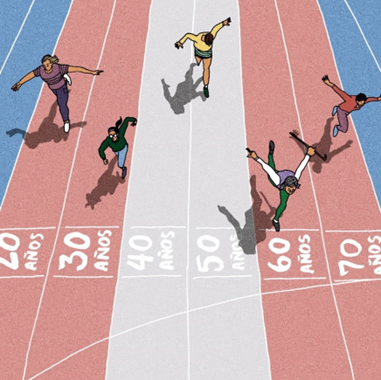

The killings and disappearances of trans people happened between 1984 and 1986, it was a social cleansing. And it was socially, culturally approved (…). This is the context where we must talk about trans old age, since for a long time, until the Gender Identity Law was passed, none of us could see ourselves as old people. We all believed we'd die young and beautiful in the casket, that was what we expected from life, because we knew we'd die young. Last year, our life expectancy was 40.7 years (…) Therefore, “our greatest revenge will be to grow old”, because when we're old we'll be able to speak and share our stories. It's like a race, the last one to arrive will be able to tell everything that happened before. That's the meaning of this emblematic motto for the trans community. 27

Meanwhile, the narrative of Ricardo Carreras14 tells a story of questioning, interpellations, indiscipline, and group construction against discrimination. Figure 4

But it also has a pejorative connotation, and it's connected to this idea, like “poor thing, he's a homosexual”, which is something people have said to me many times, “Ricardo, what a shame, such a smart, handsome man, and you're gay or homosexual". So, I prefer to say I'm an old faggot (viejo puto) (…) but it's a category to be old, it's not an issue for me, what troubles me is that people discriminate against me because I'm old, that disturbs me, it angers me, comments like “it's great you're still taking courses at your age”. And what's the issue with me taking courses at my age? (…) Personally, I prefer old man, gay old man, old faggot, but I'm old anyway, I don't fear that word much. But being called “grandpa” really gets on my nerves, because I'm not a grandfather yet, and second, I've already told my daughters that when I have grandchildren, they should call me “Ricky”, “Richard”, or “Ricardito”. 27

The protagonist of this biographical illustration was somewhat surprised and glad to receive the images, understanding point of this reinterpretation, which was used not only to promote a book, but to visibilize the stories and biographies of people who have actively fought for the recognition of their rights and gender identities.

The two experiences discussed above were conducted over the course of a year marked by the pandemic and the predominance of online communications (October 2020 to October 2021). During this period, images have been actively incorporated into research processes, becoming meaningful core elements. This has led to the preeminence of a visual culture (11 that encourages us to regard it as part of the research process and not just as an aesthetic element used in its dissemination.

Even though we had some experience in the use of images and photographs with a more illustrative intent, 1 in this study the illustration production process became as relevant as biographical production. Thus, we coined the term “biographical illustration” and part of those efforts guided our publication and design choices for the book used to communicate the results of the study analyzed in this article.

This book compiles the research testimonies of the participants in this study, using selected fragments to illustrate the process whereby one becomes a researcher, specifically in the field of Social Work. Simultaneously, the book covers the research trajectories of its protagonists and analyzes the transitions of those who experienced other transformations in the process, such as maternity and growing older. It also covers how they reassembled themselves after a watershed moment that wholly shattered their plans and their path thus far, after which they became leaders or activists in areas that they are passionate about. Most of all, the book is about lives and careers that deserve to be told, known, and visibilized.

We selected the album-book format so that readers could access these biographies in any order they wished. Ultimately, we illustrated 16 testimonies shared by 20 social workers that we expect will be especially attractive to young people who are developing an interest in science or who want to know more about one of its domains.

The illustrators participated in the production of the book from the moment the testimonies and their most relevant fragments were selected. The fragments had already been validated or approved by the interviewees; therefore, the involvement of the illustrators and their pieces took place during the middle stage of the book's production.

To show this hermeneutic link between biography and illustration, the fragments of the testimonies illustrated are complemented with the voices of the two illustrators whose work contributed to the construction of the images included in this science communication book.

Regarding this, in the testimony of one of the protagonists of the book she points out Figure 5:

Naukas15 is a science communication event and they invited me because they had issues with gender parity guidelines. So, over time, more women started appearing (…) It was really tough, because NAUKAS is very different to the social world. Second, they also wanted to expand to things that weren't necessarily scientific, I mean, they already had some people talking about science and art, and some social topics had gradually started to emerge. I began participating in 2018 and I must say it's been fantastic, because it trained me to think, it helped me to improve, to write. I joined NAUKAS because there were some winds of change already, they have 200 communicators in a single event (…) more than 40 talks lasting 10 minutes each over two days. They have a huge amount of publicity, it's a really good platform (Gabriela Jorquera16, personal communication, 2019).

The artist made the following comments regarding the production of the illustration that complements the full testimony:

I had never stopped to think about my workflow (…) The first thing I did was read the document, once or twice one day, then I read it again and highlighted what I think stands out in the testimony, what caught my attention, what I think can be illustrated. What makes sense to me, what I can use in my work. Then I checked out her talks on Naukas to find out more about her work. Well, this showed me what she looked like, it was so interesting, I found out that she uses lots of conceptual graphics in her presentations, I remember she had some tape measures, rulers, so she was familiar with conceptual graphics. In her testimony, the topic of science communication is her key word, it's what she does, it's her strength, so, based on that word (…) I spent some days thinking how I could represent the concept of scientific communication, we discussed it (…) and we finally found this element, this flower, this dandelion that has a beautiful flower that ultimately disseminates and communicates its seeds, and we thought, specifically I felt this was something female… that seeds can go anywhere thanks to the wind… (Javiera Donoso, personal communication, 2022).

Finally, we present a fragment and illustration of a narrative by another researcher whose testimony appears in the book. In this fragment, the protagonist describes her fieldwork for a doctoral thesis on topics associated with irregular immigration. In this regard, she notes:

I did my thesis on the integration processes of Latin American immigrants, that is, about the Latin community in Germany. I wanted to analyze three groups, the regular, irregular, and regularized immigrants, who as a population are very hard to find in Germany (…) So, it was a very delicate thesis, due to the issue of irregular immigration, so it was hard to arrange interviews and the whole process of getting closer to the community. But Germany's migratory policy changed midway through and the group I worked with was deported. When I defended my thesis, none of the immigrants I had worked with were still there, they had all been deported or had returned, because the legislation or the practices had changed (Claudia Silva17, personal communication, 2014).

The author of Figure 6 says the following about the production process of this illustration:

I thought it was interesting that she, as part of her thesis, tried to get closer to migrant people, maybe she thought it would be easier to do so, but they were living in the country irregularly, hiding, and so they felt a lot of mistrust and fear of being deported. I came up with the idea that they don't open the doors to their homes or the places where they're staying, erasing physical traits that are recognizable or easy to identify, because they wished to stay anonymous. That's why I depicted them initially looking at her with mistrust due to her work (Carla Salas, personal communication, 2022).

As pointed out in the introduction to this article, the illustration and testimony generation process was conducted in an online workshop held with the attendees of the VI Summer School on Qualitative Methodologies for Social Transformation in the Border Zone.

On that occasion, we highlighted the process followed to construct a biographical illustration, which in the experience of illustrators and biography producers comprises two stages: 1) research using fragments or narratives: reading and imbibing the content to be illustrated, identifying key concepts, and conceptualizing and searching for reference points; 2) image production: sketching, selecting a chromatic palette, and defining illustration/painting style.

To produce the illustrated book of research testimonies, we added a third stage of correction and adjustment which involved the interviewees or the protagonists of the biographies. They were able to influence design aspects of the two stages mentioned above, since fragment selection is occasionally conducted in accordance with the interviewees or at their suggestion.

Discussion

Science, Art, and Image

Based on the results presented and the background information considered, we discuss the concept of image and analyze its links to other related concepts such as dual interpretation and performance, within the framework of actions aimed at disseminating the knowledge produced through qualitative studies.

Studies on image 2,28,29) and the interpretations of them issued by their followers, 11 enable us to assert that images are currently faced with a contradictory situation. For some, there are no images capable of capturing reality anymore, which is the origin of the transformations of the aesthetic experience and its ambivalent power. For Soto-Calderón 2 we are dealing a shift from the question “What are images?” to their ways of doing, their performativity.

This performative nature is one of the aspects that we wish to cover in this discussion, which analyzes the fusion of illustration and the testimonies constructed upon the basis of biographical interviews. This approach acknowledges the fact that research is not only an intellectual trade, but also an artisanal and aesthetic one; thus, in this context, images become relevant since they make it possible to construct new perspectives on what we study and not merely new ways of naming things. The multidisciplinary nature of this approach yields other elements that enable us to see the world not as a reflection of itself, in the more autobiographical sense of the word, but as an interpretation of it.

Thus, imagining other people's lives, acknowledging their trajectories, illustrating their narratives becomes a double-entry interpretative task as proposed by Gadamer 29 for whom the art of explanation means that quotidian concepts which have been desacralized to some extent, like images, can have a bidirectional relationship with concepts from the social sciences. This is the case of research conducted from a biographical perspective, hence the link between interpretation and knowledge generation. Illustration operates as a double-entry mediator, translating research contents and results into graphical elements that broader audiences can understand -all audiences, regardless of their experience, with translations and bridges that include not only illustration, but also design aspects, the organization of materials, and the arrangement of concepts in a way that enables people who subscribe to a range of interpretative traditions to understand.

The above prompts us to think about artistic creations from the point of view of science and consider the role that images, or illustrations can play by connecting both fields. This is exemplified by the work of the science communicator Débora García Bello18 who seeks to build bridges between science and contemporary art.

Imagining biographies, lived lives, and bringing these lives closer to other people has thus become an intellectual challenge that we have taken on as part of our science communication duties and our wish to disseminate our findings, first through discrete exercises such as book launches, 25,27 and then more comprehensively through 16 illustrated testimonies compiled in a book to be published shortly.

In this regard, and again echoing Soto Calderón, 2 the act of interpretation demands more than merely creating narratives; it is necessary to construct images and illustrations that make it possible to actualize these narratives and thus establish a key link between subject and structure, a core element of biographical studies. 8- 9,21 Images touch the real, and when they are returned 30, they open the door to imagination, which strengthens initial interpretations and promotes other approaches, since the illustration offered does not seek totality; rather, it seeks to actualize and open.

Conclusions

This article analyzes the links between the biographical approach and the graphical representations that can be produced upon the basis of a life history, or the narratives derived from it. Using three research experiences as reference points, we explored the connections between biography and illustration, evaluating how this approach could operate as an interpretative framework in studies that employ interviews and the personal narrative genre as the main elements of their work.

We present some illustrations constructed upon the basis of biographical interviews, describing the image production process: a purposive collaboration between study participants and illustrators, who interpret fragments or narratives taken from a larger story. Creating images to give meaning to narratives and allow broader audiences to access them was one of the guiding principles of this study, which proposes a number of steps for generating science communication materials and products aimed at disseminating research findings in various fields, targeting the general public and specialists across several disciplines, including the social sciences and health care.

The images presented in this article make it possible to understand the bridges that connect biography and illustration while also shedding light on their interpretative possibilities in qualitative studies and trajectory studies.

REFERENCES

1. Rubilar, G. Imágenes de Alteridad. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica; 2013. [ Links ]

2. Soto-Calderón, A. La performatividad de las imágenes. Santiago de Chile: Metales pesados; 2020. [ Links ]

3. Rubilar, G. Narrativas y enfoque biográfico. Usos, alcances y desafíos para la investigación interdisciplinaria. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2017;6(especial):69-73. DOI: 0000-0002-4635-9380 [ Links ]

4. Balmer, D, Richards, B. Longitudinal qualitative research in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 2017;6(5):306-310. DOI: 10.1007/s40037-017-0374-9 [ Links ]

5. Calman, L, Brunton, L, Molassiotis, A. Developing longitudinal qualitative designs: Lessons learned and recommendations for health services research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013;13(14):1-10. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-14 [ Links ]

6. Tuthill, E, Maltby, A, DiClemente, K, Pellowski, J. Longitudinal Qualitative Methods in Health Behavior and Nursing Research: Assumptions, Design, Analysis and Lessons Learned, International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2020;19:1-2. DOI: 10.1177/1609406920965799 [ Links ]

7. Caïs, J, Folguera, L, Formoso, C. Investigación Cualitativa Longitudinal. Cuaderno Metodológico 52. Madrid: CIS; 2014. [ Links ]

8. Bertaux, D. Los relatos de vida. Perspectiva etnosociológica. Barcelona: Bellaterra; 2005. [ Links ]

9. Rubilar, G. Prácticas de memoria y construcción de testimonios de investigación. Reflexiones metodológicas sobre autoentrevista, testimonios y narrativas de investigación de trabajadores sociales. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Internet). 2015 Sep (citado 2022 Ago 11);16(3). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs150339 [ Links ]

10. Muñiz-Terra, L, Rubilar, G. Social Inequalities in Argentina and Chile: A Comparative Analysis of Welfare Models, Labour Policies, and Occupational Trajectories from a Biographical Perspective. Journal of Politics in Latin America (Internet). 2022 (citado 2022 Ago 11);14(2):166-189. DOI: 10.1177/1866802X211073914 [ Links ]

11. Beverley, J. Testimonio, subalternidad y autoridad narrativa. En Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Estrategias de Investigación Cualitativa. Manual de Investigación Cualitativa Vol. III, Buenos Aires: Gedisa; 2013, p. 343-360. [ Links ]

12. Obrist, H. Conversaciones con artistas contemporáneos. Santiago: Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales; 2014. [ Links ]

13. Otero, J, Diez, A, Garcia, L, Guerreo, A, Lopez D, Pantsu, A, et al. Voces que cuentan. Madrid: Planeta; 2020. [ Links ]

14. Riviere, T. Maldita tesis. Madrid: Penguin Random House; 2016. [ Links ]

15. Valles, M. Entrevistas Cualitativas. Cuaderno Metodológico 32 Madrid: CIS; 2002 [ Links ]

16. Flick, U. Introducción a la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata; 1998. [ Links ]

17. Betaux, D. Biography and society. The life history approach in the social sciences. London: SAGE; 1981. [ Links ]

18. Dombois, R. Trayectorias laborales en la perspectiva comparativa de obreros en la industria colombiana y la industria alemana. En Lulle T, Vargas P, Zamudio, L. (coord.) Los usos de las historias de vida en las ciencias sociales. Barcelona: Anthopos; 1998, p. 171-212 [ Links ]

19. Castillo, JJ, López, P. Los obreros del Polo: Una cadena de montaje en el territorio. El trabajo recobrado I. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2003. [ Links ]

20. Muñiz-Terra, L. Los (ex)trabajadores de YPF. Trayectorias laborales a 20 años de la privatización. Buenos Aires: Espacio; 2012. [ Links ]

21. Bernasconi, O. Aproximación Narrativa al estudio de fenómenos sociales: principales líneas de desarrollo. Acta Sociológica. 2011;56:9-36. [ Links ]

22. Gubrium, J, Holstein, J. Narrative practice and the coherence of persona stories. The sociological Quarterly. 1998;39(1):163-187. [ Links ]

23. Piovani, JI, Muñis-Terra, L, editores. Condenados a la reflexividad. Apuntes para repensar el proceso de investigación social. Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblos-CLACSO; 2018. [ Links ]

24. Rubilar, G. Investigación crítica en tiempos críticos: actoras, autorías y autoridad en la producción de conocimiento en Trabajo Social. Propuestas Críticas En Trabajo Social. 2022;2(3):156-178. DOI: 10.5354/2735-6620.2022.65601 [ Links ]

25. Morales, P, Aceituno, D. La resistencia de las memorias. Relatos biográficos de vidas truncadas de estudiantes y profesionales de servicio social desaparecidos y detenidos (1973-1990). Santiago de Chile: Ril Editores; 2020. [ Links ]

26. Valenzuela, P. Reseña libro Morales, P, Aceituno, D. La resistencia de las memorias: Relatos biográficos de vidas truncadas de estudiantes y profesionales del servicio social desaparecidos y ejecutados durante la Dictadura en Chile (1973- 1990). Propuestas críticas en Trabajo Social. 2022; 3:199-205. DOI: 10.5354/2735-6620.2022.66447 [ Links ]

27. Manés, R, Chachak, M, Merlo, Y, editores. Vejeces y Género. Memorias de resistencias, luchas y conquistas colectivas. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Buenos Aires; 2021. [ Links ]

28. Alloa, E. editor. Pensar la Imagen. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados; 2010. [ Links ]

29. Gadamer, HG. El giro hermenéutico. Madrid: Cátedra; 2001. [ Links ]

30. Didi-Huberman, G. Devolver una imagen. En Alloa E, editor. Pensar la Imagen. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados; 2010, p. 219-244. [ Links ]

Funding: The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the ANID/CONICYT/FONDECYT Project 1190257.

How to cite: Rubilar Donoso G. What is the Story Behind the Images? Biography and Illustration in the Background of a Trajectory Study. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2022;11(2), e2900. DOI: 10.22235/ech.v11i2.2900

Contribution of the authors: a) Study conception and design, b) Data acquisition, c) Data analysis and interpretation, d) Writing of the manuscript, e) Critical review of the manuscript. G. R. D. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: May 09, 2022; Accepted: August 26, 2022

text in

text in