Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.11 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v11i2.2917

Original Articles

Self-Care of the Informal Caregiver of the Elderly in Some Latin American Countries: Descriptive Review

1 Universidad Central del Ecuador, Ecuador

2 Universidad de Concepción, Chile, smendoza@udec.cl

Introduction:

The family is responsible for the care of the elderly, giving rise to the informal caregiver.

Objective:

To describe the self-care of the informal caregiver of the elderly in some Latin American countries.

Methodology:

Descriptive review, on the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, Web of Science, Redalyc and Dialnet; analyzing full-text scientific articles of the last 13 years (2009-2022) in Spanish, English and Portuguese. Complementary documents related to the subject were searched on Web pages of national institutions of Latin American countries.

Results:

The analysis of the 25 scientific articles and 4 selected documents allowed to identify 4 axes: concepts of care, caregiver and types of caregivers; health of the informal caregiver of the elderly; theoretical basis of self-care and implementation of programs to care for the caregiver in some Latin American countries.

Conclusions:

It is evident that the self-care of caregivers of older people is decreased, directly affecting the health of this. Several Latin American countries support the informal caregiver, however, there is still much to be done for caregivers.

Keywords: self-care; aged; caregivers.

Introducción:

La familia es la responsable del cuidado a la persona mayor, lo que da origen al cuidador informal.

Objetivo:

Describir el autocuidado del cuidador informal de personas mayores en algunos países de Latinoamérica.

Metodología:

Revisión descriptiva en las bases de datos PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, Web of Science, Redalyc y Dialnet, de artículos científicos a texto completo de los últimos 13 años (2009-2022) en idioma español, inglés y portugués; complementariamente se buscaron documentos referentes al tema en páginas web de instituciones nacionales de países latinoamericanos.

Resultados:

El análisis de los 25 artículos científicos y 4 documentos seleccionados permitieron identificar 4 ejes: conceptos de cuidado, cuidador y tipos de cuidadores; salud del cuidador informal de la persona mayor; base teórica del autocuidado, e implementación de programas para cuidar al cuidador en algunos países latinoamericanos.

Conclusiones:

Se evidencia que el autocuidado de los cuidadores de personas mayores está disminuido, lo que afecta directamente la salud de este. Varios países de Latinoamérica apoyan al cuidador informal, sin embargo, todavía hay mucho por hacer por las personas que cumplen la labor del cuidado.

Palabras clave: autocuidado; persona mayor; cuidadores.

Objetivo:

Descrever o autocuidado do cuidador informal de idosos em alguns países da América Latina.

Metodologia:

Revisão descritiva nas bases de dados PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, Web of Science, Redalyc e Dialnet; artigos científicos em texto completo dos últimos 13 anos (2009-2022) em espanhol, inglês e português; foram pesquisados documentos complementares referentes ao assunto em páginas da Web de instituições nacionais de países da América Latina.

Resultados:

A análise dos 25 artigos científicos e 4 documentos selecionados permitiu identificar 4 eixos: conceitos de cuidado, cuidador e tipos de cuidadores; saúde do cuidador informal do idoso; base teórica do autocuidado e implementação de programas de cuidado ao cuidador em alguns países da América Latina.

Conclusões:

É evidente que o autocuidado dos cuidadores de idosos está diminuído, afetando diretamente sua saúde. Vários países da América Latina apoiam o cuidador informal, porém, ainda há muito a ser feito pelas pessoas que realizam o trabalho de cuidar.

Palavras-chave: autocuidado; idoso; cuidadores.

Introduction

The life expectancy of the world population is accelerating rapidly and it is reported that if in 2010 it was 70.6 years, already by 2017 it increased to 72.2 years,1 and it is forecast that by 2025 the growth of the number of people aged 60 and over will correspond to 10 % of the total population, 2 it will double to 22 % by 2050 and triple by 2100. 3 This increase in life expectancy brings with it a series of situations that affect the health of the elderly person, which manifest themselves in loss of functional, cognitive skills, roles and the ability to perform socially defined tasks, originating, to a greater or lesser degree, dependence on the elderly person. 4 This dependency demands prolonged care, which overwhelms the care capacity of public and private health services, forcing families themselves to assume the responsibility and cost of care, making it clear that the world's health systems will continue to depend, to a large extent, on family and friends to provide unpaid care, that in the midst of this context, they become essential people to cover this care. 2,3,5

In this sense, informal care is defined as all those activities of non-professional help, this work falling on the informal main caregiver (family caregiver, primary caregiver or main caregiver). The primary caregiver is responsible and responsible for providing help and care that satisfies the basic and instrumental activities of daily living of the dependent older person. 6 In this sense, it is assuming a role for which it is not technically qualified and, generally, it is a forced and invisible activity that does not have an economic remuneration or adequate social recognition. (7, 8) This work of care and attention to the elderly produces a negative impact on the health of the caregiver, which, from the physical point of view, causes fatigue, health problems and comorbidities. In the psychological field and by having less free time, it presents a set of manifestations such as stress, feeling of anguish, irritability, sleep deterioration, sedentary lifestyle, insomnia, which can cause depression, feelings of guilt and/or frustration and impotence due to restrictions on their personal development. As a consequence of minimizing leisure and leisure activities, their family dynamics and structure is affected, because their work involves commitment and effort for which they are not prepared. 9,10 In this context, the person who provides care to others is recognized as a caregiver who, under the circumstances described, forgets about self-care. Without realizing it, this self-care deteriorates and the caregiver becomes a secondary patient and a new public health problem. 11-13

Studies carried out in Cuba, Colombia, Spain and Mexico show that it is a single person who assumes the work of care, a responsibility that is known when it begins, but not when it ends. This situation is exhausting and exposes the caregiver to experience serious health problems,7,8 that warn of the presence of sick caregivers or those at high risk of getting sick. 6 This scenario requires society, family and health personnel to consider the caregiver as a holistic being with their own needs and from this knowledge to deploy strategies, programs and policies that safeguard the health rights of the caregiver. (9,10

In this sense, it was considered necessary to carry out a narrative review as a strategy that facilitates the understanding of the self-care of the caregiver of older people in Latin American countries.

Methodology

A descriptive review was carried out, according to Guirao,14) also called traditional or narrative, on a specific topic, which examines recent or current literature.

The search for scientific evidence was carried out in repositories and journals indexed in the databases: PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, Web of Science, Redalyc and Dialnet; In addition to this recovery, the Web pages of national institutions in Latin American countries related to the subject, such as ministries of health, social welfare, and organizations such as ECLAC, were reviewed. The search strategy considered the descriptors that in the MeSH and DeCS thesauri represented the keywords in Spanish: autocuidado, persona mayor, cuidadores, with their respective translation in English (self care, aged, caregivers). For a selective recovery, the Boolean operator "AND" was included and the following inclusion criteria were applied: full-text articles, qualitative studies, primary quantitative studies, reviews, government documents, published in Spanish, English and Portuguese in the last 13 years. Duplicate articles, letters to the editor, and those unrelated to the topic were excluded.

Initially, 1,094 articles were identified, 91 duplicates were removed and 51 were excluded according to exclusion criteria, 927 articles were discarded by title and summary. Finally, 29 documents (citation 15 to 43), 25 full-text articles and 4 government documents from national and international institutions that were downloadable and/or with text available on the website were included.

The process of searching and selecting studies was simplified through the flowchart recommended by Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis (PRISMA), as shown in Figure 1. The authors, independently, carried out the review and in the analysis and contrasted their conclusions.

Results

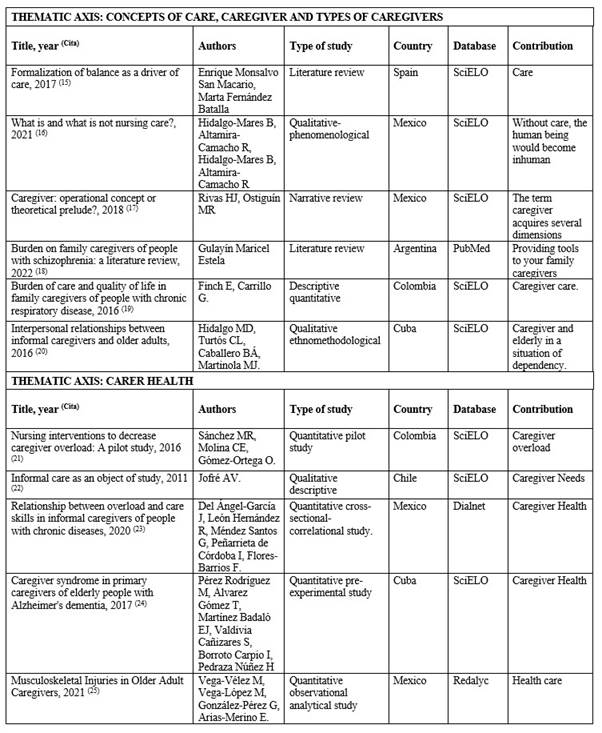

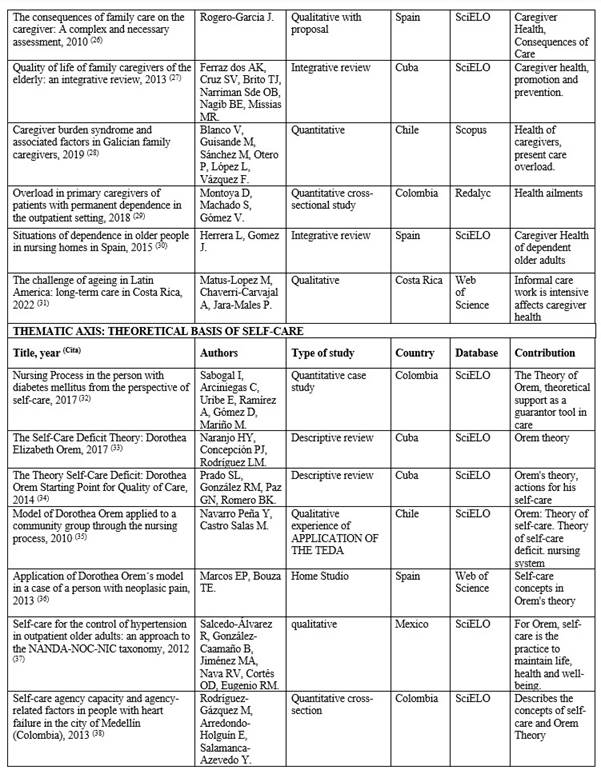

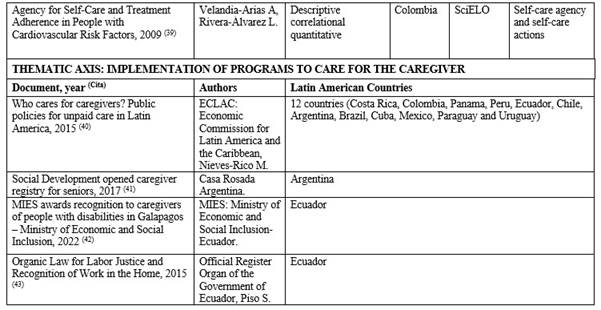

The 29 documents reviewed provided 4 thematic axis: 1) Concepts of care, caregiver and types of caregivers (6 articles); 2) the health of the informal caregiver (11 articles); 3) theoretical principles of self-care (8 articles) and 4) implementation of programs, projects and specific legislation to care for the caregiver in 12 Latin American countries (4 documents). The characteristics of the articles are presented in Table 1 T1a T1b.

Concepts of care, caregiver and types of caregivers

The word care originates from the Latin cura which, in its oldest form, was written coera and was a term used in a context of love relationship and friendship. The definition made by Collière, quoted by Monsalvo,15 points out that care is the “act of maintaining life ensuring the satisfaction of a set of indispensable needs, but which are diverse in their manifestation. The different possibilities of responding to these vital needs create and establish life habits specific to each group or person”.

The concept of care has philosophical and pragmatic implications, and evolves alongside life, culture and society. Hidalgo and Altamira,16 refer to “care is essential to the human being”, enabling human existence.

On the other hand, a caregiver is defined as the person who assists or cares for another who is affected by any type of disability, disability or disability, which prevents him from developing normally vital activities and/or social relationships, taking charge, on his own or on request, of caring for this person with a degree of dependence. Therefore, the caregiver is considered the resource, instrument and means by which specific and specialized care is provided in order to meet the needs of the person cared for, acquiring the commitment to preserve the life of the other. 17

Specifically, four types of caregivers are identified, depending on the time and training they have. Depending on the time spent on caregiving, there are two types of caregivers, the primary and the secondary. The primary caregiver is responsible for most of the care of the person, usually lives in the same home or very close to it and has a very close family relationship; the secondary caregiver leaves the least part of the time in charge of the patient, providing care for small periods. 18 According to specialized training, the informal and formal caregiver are distinguished: The informal caregiver is a person who is part of the family environment and collaborates to a greater or lesser extent in the care, but does not have specialized training; the formal Caregiver has specialized or academic training to care for the patient, being financially recognized for it. 19

According to the above, it is known as an informal primary caregiver to the person who daily, without having specialized training, is responsible for helping in the basic and instrumental activities of the person who, for any health reason, cannot perform them by himself. (19,20 They have certain common characteristics: to provide care necessary for many years and in long daily hours, in order to guarantee a better quality of life for the person cared for, in addition, in many cases, it also performs tasks of maintenance of the home, so it is mostly associated with women, culturally linked to domestic chores. (19

These informal primary caregivers do not receive financial remuneration for the help they offer, nor do they have training for care, however, they have a strong commitment to do it, due to the degree of affection or kinship they have with the person cared for. This implies that they themselves consider carrying out the care with great rigor and without limit of schedules, being then an informal, kind and free support of relatives and/or relatives, even though other agents or people from networks that do not belong to the family can also play this role. 18

Informal caregiver health

In the exercise of care, needs arise that the caregiver must satisfy from the interaction with the physical, social and cultural environment that surrounds him, in a continuous process of assimilation and adaptation to maintain his own health. It also presents the need to obtain adequate economic and social resources or to plan care, adapt the environment to ensure the success of the work, facilitate care tasks,21 all issues that, if resolved, also favor the integral maintenance of their own health.

Because of their varied functions, the caregiver should perform physical exercise and rest, maintain a correct diet, express their emotions, be supported by the family, receive information and guidance, continue their own life project, have moments of recreation and leisure, receive specialized psychological care and financial help. Consequently, it is essential that the caregiver adopts and maintains self-care practices to solve these needs and ensure their well-being and adequate quality of life. 21

The provision of care to the other is still a subject of debate, devoid of precepts that warn how far informal main care goes, being difficult to frame, because the caregiver self-imposes schedules and demands that are the result of the degree of affection and self-denial towards the person cared for. In this way, reports of morbidity and mortality of caregivers are related to the conditions under which they provide care. 22

Likewise, it can be said that this work falls especially on women, daughters, middle-aged married, with an average schooling, dedicated to the role of care for more than 6 years, provides care 7 days a week with dedication of long daily hours and in addition to care they work mostly as housewives. Caregivers report having health problems and report a regular or poor perception of their health. 23 They present health problems reporting mostly two comorbidities, the most frequent being arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Among the socioeconomic problems mention family conflicts, seeking support, loss of social relationships, lack of free time and among the psychological problems identified are anguish, irritability and fear. (24,25

Several studies indicate that caregivers present an increase in the number of medical, nursing and polypharmacy consultations, due to the presence of overload and Burnout syndrome,(26, 27) also noting that those who dedicate a lower percentage of hours to self-care present intense overload, which, together with the failure in self-care, causes them physical damage, emotional and decreased quality of life. Caregivers recognize that they do not have enough time for themselves because of the time they spend caring for the family member.28,29

A typical example of this overload is the care of the elderly, which presents significant functional losses in the performance of basic and instrumental activities of daily living, with low or no hope of recovery, being able to say, that the more activities the caregiver supplies, the greater the dependence of the elderly person.30 It is a group of people who must be provided with long-term care, so they need essential informal primary caregivers to cover this care. 31

Theoretical bases of self-care: deficit, requirements and agency

Self-care is a concept based on the Nursing Theory of Self-Care Deficit (TEDA), developed by Dorothea Orem in 1969. It has been used as a theoretical and philosophical basis to promote self-care practices for the benefit of one's own health and well-being, being considered a learned activity, which has the clear objective of adopting a behavior in specific situations of life, directed by people about themselves, towards others or towards the environment, in order to control the factors that affect the development and functioning in favor of the well-being of health and life. 32

The externally oriented self-care actions are four: 1) sequence of action for the search for knowledge; 2) sequence of action seeking help and resources; 3) interpersonal expressive actions; and 4) sequence of action to control external factors. Similarly, internally oriented self-care actions are twofold: 1) sequence of action of resource use to control internal factors; and 2) sequence of action for self-control (thoughts, feelings, orientation) that allows us to regulate internal factors and external orientations of oneself.

The understanding of the concept of self-care in nursing refers to a voluntary and intentional action with internal and external orientations that facilitates the professional to acquire, develop and perfect the skills to ensure valid and reliable information of the self-care learning systems of people. At the same time it allows them to analyze the descriptive information of this and make judgments of how they can be helped, in this case caregivers, in the learning of therapeutic self-care. 33

However, based on this theory, self-care is currently defined as the set of voluntary and intentional actions that people carry out to control internal and external factors, translating into a behavior that they must assume responsibly, putting into practice activities of promotion and conservation, which are carried out with the aim of maintaining the functioning, personal development and well-being, where the nursing professional plays an important role when, when conducting health education,34 he emphasizes the value of self-care.

Important in this theory are the requirements of self-care and refer to the necessary actions that every human being must perform for the control of the functional and developmental aspects in his life, either continuously or in specific contexts and conditions; represent the formalized goals of self-care and desired outcomes. Three types of requirements are identified: universal, developmental and health deviation. 35

Universal requirements are associated with the process of life and human functioning, common in all people, namely: 1) the entry of air; 2) the intake of water and food; 3) urinary and intestinal elimination; 4) the balance of activity and rest; 5) the balance between loneliness and social interaction; 6) the prevention of risks to life and the promotion of human functioning and interaction in groups. 35

The development requirements are internal specialized expressions, associated with the process and the specific conditions of the states of development of people, promote the necessary conditions for life and maturation and, in turn, prevent the appearance of adverse conditions, eliminating the effects of these at any time of the process of growth and development of the human being.36 They are subdivided into three: 1) provision of conditions that encourage development; 2) involvement in self-development; 3) prevention or overcoming of the negative effects that living conditions and situations may have on human development.

It is important to emphasize that among the universal requirements and those of development are the “basic conditioning factors”, which are internal and external demands, whose foundation is in the nature of human beings, as they are, considering age, sex, state of development, state of health, sociocultural factors, factors of the health care system, family system, pattern of life, environment and available resources.37 They represent a fundamental axis of nursing, because it tries to identify the gap or deficit between the potential capacity for self-care and these demands, in such a way that universal and developmental requirements are met, thus limiting deviations in health. 33

Finally, there are the requirements of deviation from health, linked to the health states associated with those disturbed functions, which is reflected when the sick person suffers an injury or has disabilities, which forces him to seek help. In case of being exposed to factors that determine a pathological state and is aware of the effects and consequences of this state, he must accept himself and learn to live with it, under diagnostic and therapeutic measures that lead to a lifestyle that promotes personal development. 37 Once this deviation occurs, the person has a "therapeutic demand for self-care" that merits the support provided by the nursing staff, in order to cover or satisfy the requirements of self-care, in relation to the conditions and circumstances themselves. 34

The self-care agency represents the set of knowledge, skills, abilities and motivation that people must possess to exercise care for themselves, therefore, people who have a developed self-care agency know how to meet their own health needs. 33 This self-care agency is a complex structure, composed of three hierarchical levels: 1) foundational capacities and dispositions; 2) power components and 3) self-care operations.

The foundational capacities and dispositions are grouped into two levels: the first, considers the sensation (proprioceptive and exteroceptive), learning, exercise and work, regulation of the position and movements of the body and its parts; while the second, considers attention, perception and memory. 38

Regarding the components of power, these are 10 specific capacities related to the ability of the person to commit to self-care: 1) ability to remain attentive and vigilant in relation to the self as an agent of self-care, as well as to the internal, external conditions and significant factors for self-care; 2) controlled use of available and necessary physical energy to initiate and continue self-care operations; 3) ability to control the position of the body and its parts in executing the movements required to initiate and complete self-care operations; 4) ability to reason within a self-care frame of reference; 5) motivations to goals oriented to self-care, consistent with life, health and well-being; 6) skills to make decisions about self-care and carry out actions; 7) ability to acquire technical knowledge about self-care, to retain it and to operationalize it from authorized sources; 8) possession of a repertoire of cognitive, perceptual, manual, communicational and interpersonal skills, appropriate to carry out self-care operations; 9) ability to separately order self-care actions in previous and subsequent systems of action to achieve the regulatory goals of care; 10) ability to carry out self-care operations in a consistent manner, integrating with relevant aspects of personal, family and community life. 38

In the case of self-care operations, these are subdivided into three types: estimates, where the conditions and individual and environmental factors of importance for self-care are evaluated; the transitional ones, in which decisions are made about what should and can be done to improve it and, finally, the productive ones, where the measures are executed to satisfy the requirements of self-care. 38

All the above shows that the self-care agency implies a dynamic and participatory process on the part of people, through which they discern about the factors that must be controlled to contribute to self-regulation itself and where it decides what it can and should do regarding the latter. This also implies reflecting on specific capacities and responsibility in the care of one's own health, in order to satisfy the requirements of self-care over time to maintain and/or improve health. 39

Thus, the self-care agent is the person who possesses these skills, but when self-care actions must be performed by another person it is called the dependent care agent, that is, people responsible for doing everything for dependent individuals, mainly infants and older adults with motor, sensory and cognitive limitations. (39 Consequently, the informal primary caregiver is essentially a dependent self-care agent when providing care to the dependent older adult.

Implementation of caregiver care programs in Latin America

In Latin America and the Caribbean, countries such as Costa Rica, Colombia, Panama and Peru have specific legislation that grants rights to caregivers. 40

Likewise, several countries have strategies, plans and programs: in Ecuador the informal primary caregiver of people with disabilities receives the Joaquín Gallegos Lara Bonus (USD 240 per month). In Chile, the Home Care Program for people with severe disabilities received (USD 35 per month) was implemented. Costa Rica provides benefits for caregivers of terminally ill people. Uruguay has a national care system project, a pilot project for partial support for caregivers of dependent people. In turn, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico and Paraguay have training programs for caregivers. 40

In addition, Argentina, through the Ministry of Social Development of the Nation, has developed a National Registry Program for Home Caregivers, with the aim of knowing the people who carry out this activity and, at the same time, providing gerontological training that ensures effective care for the elderly. 41

Ecuador, in 2011, through the Ministry of Public Health (MSP), delivered the Manual for caregivers of the dependent Older Adult, whose central axis is to educate the caregiver to develop this work. In its content there are some important elements that point to the care of the caregiver, since together with the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion (MIES), it works on projects and training programs for informal primary caregivers,42 and has achieved the recognition of home work that includes every person who performs the work of caring for the other and recognizes the right to social security to every person who perform unpaid domestic work, including caring for an immediate family member. 43

Discussion and conclusions

In the articles reviewed it is observed that the concepts of care, caregiver and types of care allow us to understand that care is essential for human existence, evolves with life, culture and society. Caregivers have intense overload that causes them physical and emotional damage and decreased quality of life; recognize that they do not have enough time for themselves, due to the time they devote to the care of the family member.44 A clear example of this is the physical effort and emotional burden to which caregivers of older people are exposed. (9, 10) In this context, it is necessary to strengthen in caregivers their self-care agency that represents the set of knowledge, skills, abilities and motivations to exercise self-care, and thus promote practices aimed at maintaining their well-being, their health and their own life.

From the above statements, it is important to emphasize that health personnel have clear guidelines to delineate self-care strategies towards the informal caregiver, provided by the Nursing Theory of Self-Care Deficit (TEDA), which allows to understand that self-care is a human skill that develops during life, through a learning process that varies according to the conditions of everyone. At the same time, it allows us to understand the significant relationship between the overload of the dependent care agent, that is, the caregiver, and the level of functional dependence of people who need him. (45 Self-care, today is a transcendental issue in the educational work that health personnel must develop, its knowledge allows to promote the promotion of health and prevention of diseases through strategies to achieve the practice of self-care in the caregiver, maintaining and / or improving their health. (45 This is where the nursing professional has an important educational role, because he must make visible the requirements of self-care and attend to the self-care needs of the informal caregiver of the dependent 39 who is not able to perceive them.

Being the self-care of the caregiver an issue of great importance, it is relevant to recognize the work of various Latin American countries that have legislation and programs that support the caregiver. However, the International Labour Organization warns that there is still a deficit in the coverage of care policies that affect both the person who needs care and the person who provides it, affecting, in this case, the health of the caregiver-elderly day. In addition, the caregiver must face the work of care without remuneration, one more problem, which affects the quality of life of the same. 46

The methodology used made it possible to reveal the situation of self-care of informal caregivers of older people in Latin American countries. The findings reveal the vulnerability of caregivers in multiple aspects, which are neglected by the characteristics of the care task. The invisible care of those who do not receive economic remuneration constitutes a public health problem that should be addressed by the policies of Latin American countries. While some countries have moved towards systems of care, training caregivers and promoting their self-care, efforts are still insufficient.

Political will is needed to make visible a job that should enjoy the same rights as other workers. It is necessary to advance in policies that ensure, on the one hand, the financing of this work and on the other, the training and opportunities to carry out self-care practices of the informal caregiver.

This work could prompt other researchers to generate research on this problem. Among the limitations of this article, it is considered that including gender as a descriptor could have yielded stronger results in terms of the reality of self-care of informal caregivers.

REFERENCES

1. Grupo Banco Mundial. Esperanza de vida al nacer, total (años) (Internet). 2017 (citado 9 abr 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN [ Links ]

2. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Organización Mundial de la Salud. La cantidad de personas mayores de 60 años se duplicará para 2050; se requieren importantes cambios sociales (Internet). 2015 (citado 5 jul 2021). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=articl%20e&id=11302%3Aworld-population-over-60-to-double-%202050&Itemid=1926&lang=es [ Links ]

3. Organización de las Naciones Unidas. Envejecimiento (Internet). 2019 (citado 7 ene 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.un.org/es/global-issues/ageing#:~:text=Seg%C3%BAn%20datos%20del%20informe%20%22Perspectivas,tener%2065%20a%C3%B1os%20o%20m%C3%A1s . [ Links ]

4. Loredo-Figueroa M, Gallegos-Torres R, Xeque-Morales AS, Palomé-Vega G, Juárez-Lira A. Nivel de dependencia, autocuidado y calidad de vida del adulto mayor. Enfermería Universitaria. 2016;13(3):159-165. DOI: 10.1016/j.reu.2016.05.002 [ Links ]

5. Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas América Latina y el Caribe. Una Mirada sobre el Envejecimiento (Internet). 2017 (citado 12 feb 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://lac.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Una%20mirada%20sobre%20el%20envejecimiento%20FINAL21junB.pdf [ Links ]

6. Cordero CM, Ferro GB, García VM, Domínguez ÁJ, et al. Cuidado informal al adulto mayor encamado en un área de salud. Ciencias Médicas (Internet). 2019 (citado 11 feb 2022);(2):195-203. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://revcmpinar.sld.cu/index.php/publicaciones/article/view/3786 [ Links ]

7. Carreño MS, Chaparro DL. Adopción del rol del cuidador familiar del paciente crónico: Una herramienta para valorar la transición. Investig andin (Internet). 2018 (citado 11 feb 2022);20(36):39-54. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/2390/239059788004/ [ Links ]

8. Camargo-Sánchez A, Pachón-Rodríguez H, Azevedo D, Parra-Chico W, Niño-Cardozo C. El tiempo en el cuidador del paciente con cáncer, un abordaje cualitativo. Rev cienc cuidad (Internet). 2018 (citado 22 oct 2021);15(1):123-34. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6249183 [ Links ]

9. Flores N, Jenaro C, Moro L, Tomsa R. Salud y calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares y profesionales de personas mayores dependientes: estudio comparativo. Eur. J investig. health psychol educa (Internet). 2015 (citado 2 jun 2021);4(2):79-88. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.readcube.com/articles/10.30552/ejihpe.v4i2.73 [ Links ]

10. Díaz AH, Lemus FN, Gonzáles CW, Licort MO, Gort CO. Repercusión ética del cuidador agotado en la calidad de vida de los ancianos. Rev Ciencias Médicas (Internet). 2015 (citado 18 mar 2021);19(3):478-90. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1561-31942015000300011&lng=es . [ Links ]

11. DePasquale N, Bangerter L, Williams J, Almeida D. Certified Nursing Assistants Balancing Family Caregiving Roles: Health Care Utilization Among Double- and Triple-Duty Caregivers. The Gerontologist (Internet). 2016 (citado 5 ago 2021);56(6):1114-23. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/56/6/1114/2952883 [ Links ]

12. Metzelthin S, Verbakel E, Veenstra M, Exel J, Ambergen A, Kempen G. Positive and negative outcomes of informal caregiving at home and in institutionalised long-term care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr (Internet). 2017 (citado 10 dic 2021);17(1):232. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12877-017-0620-3.pdf [ Links ]

13. Fradua I, Marañón U, Prieto R, Cabrera M. Cuidado, valores y género: la distribución de roles familiares en el imaginario colectivo de la sociedad española. Inguruak (Internet). 2019 (citado 20 dic 2021);(65):90-108. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://inguruak.eus/index.php/inguruak/article/view/133 [ Links ]

14. Guirao G. Utilidad y tipos de revisión de literatura. Ene (Internet). 2015 (citado 27 jun 2022);9(2). DOI: 10.4321/S1988-348X2015000200002 [ Links ]

15. Monsalvo SM, Fernández BM. Formalización del equilibrio como motor del cuidado (Internet). 2017 (citado 22 dic 2021);11(3):737. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1988-348X2017000300004&lng=es.%20%20Epub%2023-Nov-2017 [ Links ]

16. Hidalgo-Mares B, Altamira-Camacho R, Hidalgo-Mares B, Altamira-Camacho R. ¿Qué es y qué no es el cuidado de enfermería? Enfermería Actual de Costa Rica (Internet). 2021 (citado 6 may 2022);(40). DOI: 10.15517/revenf.v0i39.40788 [ Links ]

17. Rivas HJ, Ostiguín MR. Cuidador: ¿concepto operativo o preludio teórico? Enferm univ (Internet). 2018 (citado 6 sep 2021);8(1). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://revista-enfermeria.unam.mx:80/ojs/index.php/enfermeriauniversitaria/article/view/273 [ Links ]

18. Gulayín ME. Carga en cuidadores familiares de personas con esquizofrenia: una revisión bibliográfica. Arg Psiquiatr (Internet). 2022 (citado 3 may 2022);33(155):50-65. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revistavertex.com.ar/ojs/index.php/vertex/article/view/135/86 [ Links ]

19. Pinzón E, Carrillo G. Carga del cuidado y calidad de vida en cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad respiratoria crónica. Rev Fac Nac Salud Pública (Internet). 2016 (citado 6 sep 2021);34(2):9. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-386X2016000200008 [ Links ]

20. Hidalgo MD, Turtós CL, Caballero BÁ, Martinola MJ. Relaciones interpersonales entre cuidadores informales y adultos mayores. Rev Nov Pob (Internet). 2016 (citado 14 sep 2021);12(24):77-83. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1817-40782016000200006 [ Links ]

21. Sánchez MR, Molina CE, Gómez-Ortega O. Intervenciones de enfermería para disminuir la sobrecarga en cuidadores: Un estudio piloto. Rev Cuid (Internet). 2016 (citado 18 jul 2021);7(1). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S2216-09732016000100005&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es [ Links ]

22. Jofré AV. El cuidado informal como objeto de estudio. Cienc Enferm (Internet). 2011 (citado 12 mar 2022);17(2):7-8. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-95532011000200001 [ Links ]

23. Del Ángel-García J, León Hernández R, Méndez Santos G, Peñarrieta de Córdoba I, Flores-Barrios F. Relación entre sobrecarga y competencias del cuidar en cuidadores informales de personas con enfermedades crónicas. MedUNAB. (Internet). 2020 (citado 22 mar 2022);23(2):233-41. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revistas.unab.edu.co/index.php/medunab/article/view/3878/3282 [ Links ]

24. Pérez Rodríguez M, Álvarez Gómez T, Martínez Badaló EJ, Valdivia Cañizares S, Borroto Carpio I, Pedraza Núñez H. El síndrome del cuidador en cuidadores principales de ancianos con demencia Alzhéimer. Gac Médica Espirituana. (Internet). 2017 (citado 22 mar 2022);19(1):38-50. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1608-89212017000100007 [ Links ]

25. Vega-Vélez M, Vega-López M, González-Pérez G, Arias-Merino E. Lesiones musculoesqueléticas en cuidadores adultos mayores. Rev Médica Inst Mex Seguro Soc (Internet). 2021 (citado 22 may 2022);59(4). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/4577/457769668009/html/ [ Links ]

26. Rogero-García J. Las consecuencias del cuidado familiar sobre el cuidador: Una valoración compleja y necesaria. Index de Enfermería (Internet). 2010 (citado 12 feb 2022);19(1):47-50. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962010000100010 [ Links ]

27. Ferraz dos Anjos Karla, Cruz Santos Vanessa, Brito Teixeira Jules Ramon, Narriman Silva de Oliveira Boery Rita, Nagib Boery Eduardo, Missias Moreira Ramon. Calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares de ancianos: una revisión integradora. Rev Cubana Enfermer (Internet). 2013 (citado 15 may 2022);29(4). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03192013000400004&lng=es . [ Links ]

28. Blanco V, Guisande M, Sánchez M, Otero P, López L, Vázquez F. Síndrome de carga del cuidador y factores asociados en cuidadores familiares gallegos. Esp Geriatr Gerontol (Internet). 2019 (citado 15 feb 2022);54(1):19-26. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-espanola-geriatria-gerontologia-124-pdf-S0211139X18305547 [ Links ]

29. Montoya D, Machado S, Gómez V. Sobrecarga en los cuidadores principales de pacientes con dependencia permanente en el ámbito ambulatorio. Medicina UPB (Internet). 2018 (citado 17 feb 2022);7(2):89-96. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/1590/159056349001/html/ [ Links ]

30. Herrera L, Gómez J. Situaciones de dependencia en personas mayores en las residencias de ancianos en España. Ene (Internet). 2015 (citado 10 sep 2021);9(2). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.ene-enfermeria.org/ojs/index.php/ENE/article/view/546 [ Links ]

31. Matus-Lopez M, Chaverri-Carvajal A, Jara-Males P. The challenge of ageing in Latin America: long-term care in Costa Rica. Saúde E Soc (Internet). 2022 (citado 10 may 2022);31(1):e201078. DOI: 10.1590/S0104-12902021201078 [ Links ]

32. Sabogal I, Arciniegas C, Uribe E, Ramírez A, Gómez D, Mariño M. Proceso de Enfermería en la persona con diabetes mellitus desde la perspectiva del autocuidado. Rev Cubana Enfermer (Internet). 2017 (citado 8 may 2021);33(2). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://revenfermeria.sld.cu/index.php/enf/article/view/1174 [ Links ]

33. Naranjo HY, Concepción PJ, Rodríguez LM. La teoría Déficit de autocuidado: Dorothea Elizabeth Orem. Gac Méd Espirit (Internet). 2017 (citado 26 jul 2021);19(3):89-100. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1608-89212017000300009 [ Links ]

34. Prado SL, González RM, Paz GN, Romero BK. La teoría Déficit de autocuidado: Dorothea Orem punto de partida para calidad en la atención. Rev Med Electron (Internet). 2014 (citado 20 feb 2022);36(6):835-45. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1684-18242014000600004&lng=es . [ Links ]

35. Navarro Peña Y, Castro Salas M. Modelo de Dorothea Orem aplicado a un grupo comunitario a través del proceso de enfermería. Enferm glob (Internet). 2010 (citado 10 sep 2022);(19). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412010000200004&lng=es . [ Links ]

36. Marcos EP, Bouza TE. Rincón científico Application of Dorothea Orem´s model in a case of a person with neoplasic pain. Gerokomos (Internet). 2013 (citado 10 dic 2022);24(4):168-77. DOI: 10.4321/S1134-928X2013000400005. [ Links ]

37. Salcedo-Álvarez R, González-Caamaño B, Jiménez MA, Nava RV, Cortés OD, Eugenio RM. Autocuidado para el control de la hipertensión arterial en adultos mayores ambulatorios: una aproximación a la taxonomía NANDA-NOC-NIC. Enferm univ (Internet). 2012 (citado 2 may 2022);9(3):25-43. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-70632012000300004&lng=es . [ Links ]

38. Rodríguez-Gázquez M, Arredondo-Holguín E, Salamanca-Azevedo Y. Capacidad de agencia de autocuidado y factores relacionados con la agencia en personas con insuficiencia cardíaca de la ciudad de Medellín (Colombia) Enferm glob (Internet). 2013 (citado 2 ago 2021);12(2). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412013000200009 [ Links ]

39. Velandia-Arias A, Rivera-Álvarez L. Agencia de Autocuidado y Adherencia al Tratamiento en Personas con Factores de Riesgo Cardiovascular. Rev salud pública (Internet). 2009 (citado 10 feb 2022);11(4):538-548. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0124-00642009000400005&lng=en . [ Links ]

40. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, Nieves-Rico M. ¿Quién cuida a las cuidadoras? Políticas públicas para el cuidado no remunerado en América Latina (Internet). 2015 (citado 26 abr 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/events/files/nieves_rico.pdf [ Links ]

41. Casa Rosada Argentina. Desarrollo Social abrió registro de cuidadores para personas mayores (Internet). 2017 (citado 2 may 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.casarosada.gob.ar/informacion/actividad-oficial/9-noticias/38814-desarrollo-social-abrio-registro-de-cuidadores-para-personas-mayores [ Links ]

42. Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social-Ecuador. MIES entrega reconocimiento a cuidadoras y cuidadores de personas con discapacidad en Galápagos - Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social (Internet). 2018 (citado 6 may 2022). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.inclusion.gob.ec/mies-entrega-reconocimiento-a-cuidadoras-y-cuidadores-de-personas-con-discapacidad-en-galapagos/ [ Links ]

43. Registro Oficial Órgano del Gobierno del Ecuador, Piso S. Ley Orgánica para la Justicia Laboral y Reconocimiento del Trabajo en el Hogar. (Internet) 2015 (citado 6 may 2022);16. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/ecuador_-_ley_org._para_la_justicia_labora_y_reconocimiento_del_trabajo_en_el_hogar.pdf [ Links ]

44. Flores G Elizabeth, Rivas R Edith, Seguel P Fredy. Nivel de sobrecarga en el desempeño del rol del cuidador Familiar de adulto mayor con dependencia severa. Cienc. enfermo (Internet). 2012 (citado 20 ago 2022);18(1):29-41. DOI: 10.4067/S0717-95532012000100004. [ Links ]

45. Martínez-Rueda Rosmary, Dallos Santander Diana Carolina, Gutiérrez Galvis Adriana Rocío, Mantilla Pastrana María Inés. Conocimientos y prácticas de autocuidado en jugadores de rugby. Rev Cubana Invest Bioméd (Internet). 2020 Jun (citado 20 ago 2022);39(2):e360. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03002020000200018&lng=es. Epub 01-Jun-2020 [ Links ]

46. Organización Internacional del Trabajo. El trabajo de cuidados y los trabajadores del cuidado para un futuro con trabajo decente (Internet). 2019 (citado 12 abr 22). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_737394.pdf [ Links ]

Cómo citar: Guato-Torres P, Mendoza-Parra S. Self-care of the informal caregiver of the elderly in some Latin American countries: Descriptive review. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2022;11(2):e2917. DOI: 10.22235/ech.v11i2.2917

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. P. G. T. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; S. M. P. in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: June 01, 2022; Accepted: September 27, 2022

texto en

texto en