Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.11 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v11i2.2792

Original Articles

Surviving Cancer: Narratives of a Group of People’s Experiences

1 Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Colombia

2 Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Colombia, jhon.osorio@upb.edu.co

Objective:

Our aim was to understand cancer survivors’ meanings of life after their cancer experience.

Method:

This was a biographical and qualitative study carried out from a naturalistic approach. We conducted in-depth interviews with five cancer survivors and analyzed the resulting content.

Results:

We found four categories: the stigma of cancer in survivorship; survivorship support networks; self-care in survivorship; and transcendence. The results gave us a greater understanding of survivors’ needs and how they are being addressed by healthcare providers in Colombia.

Conclusions:

Cancer survivors shift towards a more holistic view of their health and transform the meaning of their life based on reflection and belief in God. Therefore, the nursing practice should focus on assisting them in these changes since healing.

Keywords: survivors; neoplasms; social stigma; social support

Objetivo:

Comprender los significados que las personas que sobreviven al cáncer le dan a su vida después de este suceso.

Método:

Estudio realizado desde el paradigma naturalista con enfoque cualitativo; se aplicó el método biográfico de historia de vida, mediante entrevistas en profundidad a cinco sobrevivientes al cáncer. Se realizó análisis de contenido.

Resultados:

Emergieron cuatro categorías: el estigma del cáncer en la sobrevida; redes de apoyo para la sobrevida; cuidado de sí en la sobrevida, y trascendencia. Los datos permitieron alcanzar un mayor nivel de comprensión de sus necesidades y cómo están siendo atendidas por los prestadores de servicios de salud en Colombia.

Conclusiones:

Los sobrevivientes transforman sus cuidados hacia una perspectiva más integral y reinterpretan su nueva vida a partir de la reflexión y la creencia en Dios. En enfermería, los cuidados son orientados a acompañar los principales cambios en el continuo de la sobrevida que se dan desde el momento de la curación.

Palabras clave: sobrevivientes; neoplasias; estigma social; apoyo social.

Objetivo:

Entender os significados que as pessoas que sobrevivem ao câncer dão às suas vidas após esse evento.

Método:

Um estudo baseado no paradigma naturalista com uma abordagem qualitativa, o método de história de vida biográfica foi aplicado através de entrevistas em profundidade com cinco sobreviventes de câncer. Foi realizada uma análise de conteúdo.

Resultados:

Quatro categorias emergiram: o estigma do câncer sobre a sobrevivência; redes de apoio à sobrevivência; autocuidado sobre a sobrevivência; e transcendência. Os dados permitiram um maior nível de compreensão de suas necessidades e de como eles estão sendo tratados pelos prestadores de serviços de saúde na Colômbia.

Conclusões:

Os sobreviventes transformam seus cuidados em uma perspectiva mais holística e reinterpretam sua nova vida com base na reflexão e na crença em Deus. Na enfermagem, o cuidado é orientado para acompanhar as principais mudanças na continuidade da sobrevivência que ocorrem a partir do momento da cura.

Palavras-chave: sobreviventes; neoplasmas; estigma social; apoio social

Introduction

Cancer is a growing global health concern, 1 with over 18 million new cases reported in 2018 and a high incidence of lung cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer. 2 Additionally, mortality rates are high, despite signs that they may be declining for some cancers that are amenable to early detection or with advancements in treatment, which has increased the survival of patients with this disease. 2,3

According to the United States National Cancer Institute, survival is defined as the time from treatment completion until death. In addition, it includes the physical, psychological, social, and economic factors associated with the disease, as well as patients’ access to healthcare and follow-up care, including drug therapy for some types of cancer, management of the late effects of a treatment or a potential second cancer, and quality of life improvement. 4

Several studies have demonstrated that when people are diagnosed with cancer, they begin to reorganize their daily life, experience uncertainty, and use various coping strategies.5,6 Additionally, symptoms such as sleep disorders, fatigue, and pain, as well as feelings such as social isolation, hopelessness, frustration, and powerlessness start to appear. These symptoms and feelings, which are thought to be side effects of cancer or its treatment, disrupt their daily lives and lead them to quit their jobs or feel that their performance falls short of expectations, whether at work, in school, or in their role as a family member. These factors, indeed, affect their quality of life and cause changes in their self-image, which persist even into survivorship. 7,8

A growing number of cancer patients have completed their treatments and are now living with a disease that has been successfully treated but in a condition that still needs changes and adjustments. 9 This phenomenon, which health professionals are still unaware of, should be investigated to understand how these people are affected physically, psychologically, and socially over time. 10 Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to comprehend how cancer survivors see life after their cancer experience. Our specific objectives are to understand changes in their everyday life, relational dynamics, and health practices.

Methodology

This study was conducted using a naturalistic (or interpretive) approach, in which reality is constructed based on intersubjectivity to comprehend the world through individuals’ appropriation of it. This approach uses experiences to understand the world and recognize subjectivities, as well as the impact of historical, cultural, and social aspects on it.11 In line with this approach, we followed a qualitative methodology and particularly selected the biographical method, through which experiences can be identified in narratives centered on a specific period of a person’s life or on a particular aspect of it. 12 The study population consisted of cancer patients who had completed their treatment and had survived for four years or longer.

Participants

The sample size was determined by theoretical saturation. Data saturation occurs when no additional information is provided by new participants and data already collected are repeated. 13 To avoid this, special emphasis was placed on choosing individuals who had undergone a cancer experience and were willing to share it in depth. Our goal was to understand their evolution and the changes they experienced in their daily lives, in their health practices, and in their relationships with others, as well as the circumstances under which these changes took place.

Participants were selected using criterion and snowball sampling. 14 These two techniques allowed us to identify cases of interest from individuals who met the eligibility criteria and were referred by others to participate. We -the authors of this paper-and participants had never met before. The five participants were referred by people we know and were gradually contacted as the analysis continued until theoretical saturation was reached. Inclusion criteria were the following: 1) being aged 18 or older, 2) having survived cancer without recurrence for four years or longer, and 3) having sound cognitive functions to participate in the interviews.

Once participants were selected, we informed them of the study’s objectives, how they would participate, and why it is important for us, as researchers, to learn about their cancer survivorship experience, which we would attempt to reconstruct with them. We also explained to them what the interviews and meetings were about, as well as how long they would be and where they would take place. Seven people were contacted via phone, but two of them declined to take part in the study because they could not find the time to attend the meetings.

Data collection

Data were collected via in-depth interviewing. Each participant was required to attend two meetings: in the first meeting, they were asked how their life had changed after being informed that they were cancer-free, and, in the second meeting, we further explored thematic areas of interest identified in the narratives of the first interview. Each meeting’s location and time were agreed upon with each participant (often at their home) and lasted up to two hours. For the interviews, we applied three principles: non-directive interviewing, rapport, and reflexivity. 15

All interviews were recorded in their entirety using a digital voice recorder with a 32-GB storage capacity and transcribed verbatim down to the smallest details such as language slips, hesitations, idioms, and silences or pauses. A notepad was also employed to take detailed notes on the participants’ facial expressions and body language throughout the interviews. Participants’ names were changed to protect their identities.

Data análisis

After transcribing the content of the interviews, it was analyzed considering the following three stages: pre-analysis, exploration, and data processing. 16 In pre-analysis, we were able to select the theoretical elements to be used. In exploration, the elements chosen in the first stage were thoroughly examined to define units of analysis and possible codes. In data processing, data were categorized according to the theoretical concepts and semantic criteria and grouped and regrouped based on common characteristics. During categorization and analysis, objectivity, validity, and reliability were assured by documenting the entire research process in analytical memos, which contained thoughts, theoretical issues, and questions.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana and it adhered to the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice. In addition, it was classified as minimal-risk research, in accordance with Ruling 8430 of 1993 by Colombia’s Ministry of Health. All participants signed the informed consent form after receiving information about the study and its procedures, advantages, and potential risks.

Rigor criterio

The rigor criteria applied in this study were credibility, through evidence on the survivorship experience as described by the participants in their narratives; transferability, through data on the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the subjects who participated in the study; confirmability, through comparisons between our findings and the existing literature and authors’ reflexivity and neutrality regarding the phenomenon under study; and auditability, through the different reviews made to the study (from the approval by the ethics committee to the various peer reviews along the publication process). 17

Results

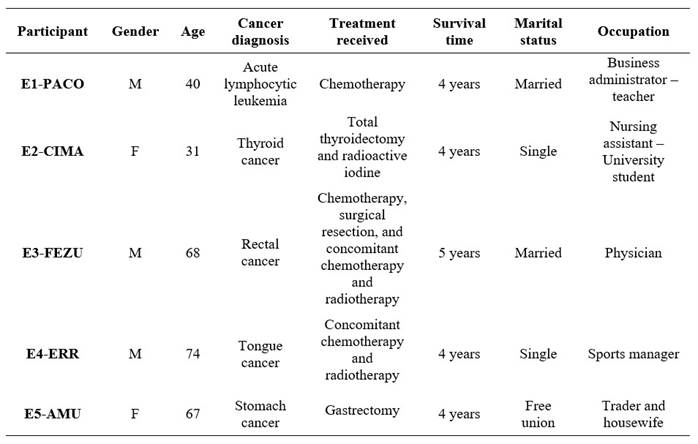

Five participants were interviewed. Their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants

Source: Own elaboration (2020)

After analyzing the content of the interviews, we defined the following four categories: 1) the stigma of cancer in survivorship, with two subcategories: the mark left by cancer and others label us; 2) survivorship support networks, with two subcategories: family support and other support networks; 3) self-care in survivorship, with three subcategories: changes in lifestyle, health services, and practices that enhance emotional well-being; and 4) transcendence, with four subcategories: faith in God as a mediator of survival, survivorship as an introspective experience, new values in survivorship, and changes in the perception of life. These categories, along with their corresponding subcategories, are described below.

The stigma of cancer in survivorship

A cancer experience affects not only those who suffered it, but also their immediate family and social circle. It reminds them of what they went through and identifies them as cancer survivors in society, which is not always viewed positively because it ends up becoming a stigma. This stigma results from other people’s appreciation of the collective imaginaries about cancer, which participants must inevitably deal with in survivorship, making them feel singled out for having experienced a condition for which they were not prepared.

This stigma should be not seen as harmful because the idea behind it is not to reject or discriminate cancer survivors. People do not intend to stigmatize; rather, they wish to support those who have or had cancer. This stigmatization, however, causes problems for cancer survivors because it limits them and makes them feel that they cannot do certain activities. Moreover, it is a constant reminder of the disease and the possibility of metastasis or recurrence.

The mark left by cancer

Participants used the words “mark” and “scar” to describe how cancer had profound effects on their bodies, emotions, and thoughts. Physical scars refer to the physical and physiological changes brought on by the disease and its treatments. Emotional scars are caused by the pain and suffering that come with having a disease of such a social and medical significance. Having their body underwent various treatments that caused it changes affects their self-image and, in turn, becomes a source of discomfort, nonconformity, and sadness.

Even I, a doctor, became fooled into thinking that once the treatment was over, I could finally close that chapter and return to my work and previous life. But NO, it’s not like that at all. Cancer leaves a huge mark on us (E3-FEZU).

Everyone who has cancer goes through the same process (silence). Every time they mention cancer to you, you know that you’re going to die or that even if you survive, there will be many limitations because life will never be the same again. Even if you’re the same person you used to be, there is a scar… (E2-CIMA).

Others label us

Participants recounted how certain family members, coworkers, acquaintances, neighbors, and the health professionals who look after them singled them out for having had cancer. Physical changes like a visible scar, being skinny, needing treatment for cancer, or just having a history of the disease are all factors that lead to this stigmatization. In other words, what has been a mark for cancer survivors is seen as a reason to label them as sick: others believe that they cannot exert themselves physically or expose themselves to harmful situations like stress, changes in weather, prolonged or physical work, and nights out.

And, well, family shows a lot of consideration, but one must know how to handle it. You have to start saying things like ‘No (silence). I can do it...’ You have to take the first step (E1- PACO).

So, we were able to move out in December. We had to go somewhere else in search of that… in search of a little bit of anonymity... Even though we moved to a place not far from where we used to live, no one recognized us. So, it was great! I like anonymity because no one knows your story (silence), which is somehow intense… (E1-PACO).

Survivorship support networks

A support network is key to recover from the cancer experience and live through the negative effects and stigma. Support networks are made up of family members, friends, coworkers, and other acquaintances. They have a small number of members because they call for strong bonds that already existed or that were forged through hardship and that can withstand the course of the disease, the effects of treatment, and any changes in the patient’s mood.

These networks provide emotional and financial support to deal with unique circumstances such as changes in health, emotional ups and downs, introspection, economic issues, return to work or changing roles, and difficulties in accessing health services.

Family support

The primary source of support for cancer survivors is family, which includes partners, parents, siblings, and children, or at least some of them. These individuals already had a bond with cancer survivors before they were diagnosed and remained by their side throughout the course of their disease and treatment. To provide the necessary support, those in this network must reorganize their job activities to have enough time to accompany the survivor to leisure activities, doctor appointments, or health-related errands.

and with a family that always supported me and that never, never abandoned me, never stopped caring for me, and always put up with me (E4-ERR).

People try, but at the end there is no one. Only three people remained by my side: my mother, my sister, and my wife (E1-PACO).

Other support networks

Friends, coworkers, and other acquaintances make up other support networks that are necessary for cancer survivors. These networks have a small number of members because, during the course of the disease, social relationships deteriorate, survivors are pickier about building new relationships, and they only talk about their cancer experience and survivorship with a limited number of people.

Participants explained that the network of friends offers emotional support through listening, encouragement for introspection, self-esteem improvement, and company in social activities, whereas the network of coworkers provides support to deal with their return to work and changing roles.

So, when I returned to work, there was clearly a lot of consideration, but I had a great team. They are more like friends than coworkers (…) It’s not about finding someone who wants something other than to be with you... Sharing work experiences is a form of support (E1-PACO).

But then they changed my position... My boss told me that I couldn’t... when I had the cortisol problem and stuff… that I couldn’t be under a lot of pressure. So, they transferred me to a different position. It was hard for me; I didn’t want a different position… My coworkers supported me… but I didn’t fully understand things until I started leaving earlier. I couldn’t believe that I left work at five in the afternoon (...) I was able to see how beneficial that support was to me (E2-CIMA).

Self-care in survivorship

Self-care refers to cancer survivors’ responsible and conscious decision to engage in activities that are beneficial to their health and well-being. This is understood from their new perspective of health, which gives it the highest value. Under the premise of taking care of themselves, cancer survivors adopt healthy habits concerning nutrition, physical activity, and giving up substances that are harmful to their health. Additionally, they realize the importance of receiving healthcare to deal with the effects of cancer and follow-up care in survivorship.

Changes in lifestyle

Participants reported having changed their health practices in order to live a healthy life, improve their well-being, manage and cope with the effects of cancer or its treatments, and maintain an optimal quality of life. For cancer survivors, adopting healthy habits is crucial because after recovery, their perception of health changes, and keeping healthy becomes very important to them.

The disease requires a great deal of attention; you need a very special diet, for instance. You begin to understand that eliminating fats, as well as carbohydrates and others, from your diet is necessary for improving your quality of life (E1-PACO).

I always bring a lunch box with me because I don’t know how food is prepared in other places, and I use olive oil, which was the one the nutritionist recommended. That’s why I better bring my lunch box (E5-AMU).

Health services

Participants reported having formed deep bonds with the healthcare institutions they attended because they constantly require follow-up care, specialized medical attention, and medications. They see these services as crucial to their self-care and to deal with the effects of the disease, which is why they attend all medical check-ups and strictly follow any therapy advice. They, however, have also encountered a variety of problems in accessing health services, such as difficulties in scheduling appointments, drug delivery delays, and not receiving follow-up care. They sometimes have turned to legal action to receive the necessary medical care.

Every month-the monthly tour (laugh)-I have to go there to request authorization for the medications that are not covered by the health plan. Besides, I have to visit the hepatologist (E3-FEZU).

I never make decisions about dental procedures or other relevant matters without first asking my oncologist. I underwent radiotherapy and chemotherapy, which almost left me without a jaw. I also have to take care of myself (E4-ERR).

The nutritionist recommends me foods that I should consider incorporating into my diet. She says: ‘Try this and let me know how it goes (E5-AMU).

Practices that enhance emotional well-being

Survivorship calls for time to “heal” emotionally because, during the course of the disease, some issues remained unsolved. Additionally, cancer survivors need emotional fortitude to deal with the agony and uncertainty that come with returning to work, dealing with changes at the workplace, rearranging their everyday life, and going to medical check-ups with the fear of recurrence. Hence, they try to improve their emotional health through practices that encourage them to express their feelings and manage stress.

I believe that we need … to be serene and calm, not agitated because that overwhelms us and makes us sick (E5-AMU).

One needs time to heal because although the physiological process is now over, the internal, mental aspect needs to recover (E2-CIMA).

I’m the secretary of a magic group (laugh), and I read. I always bring a book with me (E3-FEZU).

Transcendence

Transcendence emerges as a result of the experience lived by cancer survivors after feeling vulnerable and facing the impending threat of death. This encounter causes them to change the way they perceive themselves and their surroundings.

Transcendence is mediated by how cancer patients approach religious beliefs and faith in God as a support to keep hope during the course of the disease and that is then maintained in survivorship to deal with uncertainty and the difficulties of restructuring life. Moreover, they undergo introspective processes that heighten self-awareness, elevate the value of life and health, and change their perceptions of life by emphasizing its value.

Faith in God as a mediator of survival

Some participants described their cancer experience as being the pivotal and crucial factor that made them appreciate life and feel the approaching death. For this reason, they turned to God for support and gave their life to Him so that He could determine the outcome. Hence, as survivors, participants believe that their faith in God enabled them to defeat the disease and strengthened their confidence in the treatments and their hope for a full recovery.

Disease teaches you that you are closer to death than life and causes big changes in you (E1-PACO).

And accept this; leave everything in God’s hands. In the end, He is the one who decides our fate (E4-ERR).

The Lord gave me the patience to wait for healing. Only He knows when my story ends (E5-AMU).

Survivorship as an introspective experience

Despite achieving a certain level of stability during survivorship, participants continue to reflect on their experience and recognize that the way they see various life situations has changed. They have thought about cancer and what caused it, trying to accept and understand the past rather than seeking explanations for what happened. This leads cancer survivors to reflect on themselves and how their perspectives have changed as a result of strengthening their spiritual and emotional foundations, understanding human vulnerability, and placing family and themselves above other aspects.

Well then, one wonders: Who am I? Why am I here? What is life? (E3- FEZU).

I realized that I’m not the only one who’s right, that I’m not the most important person, and that there are others (E3-FEZU).

At this point, I believe that there is much to say that has not yet been said because most of us who have something to say are not here anymore, as only 5% of cancer patients survive with a fair quality of life (E1-PACO).

New values in survivorship

The transformation of thinking described by the participants showed that confronting the disease and the possibility of not having more time to enjoy life and family led them to reflect on the value of tangible and intangible things. As a result, during survivorship, they reorganized their priorities and gave greater value to life, health, and time to share with family and loved ones, as they felt that their loss would leave them without anything. In short, they started to consider the whole, the most valuable, the really important things.

You learn to appreciate life, what you have, to take care of yourself (E2-CIMA).

My thoughts have changed. I appreciate everything more, not material things; now my health, life, and family are more important to me (E3-FEZU).

If you lose your job, you can get another one; if your boyfriend breaks up with you, you get another one; but if you get sick, then it’s more (silence) .... Those are the really important things in life (E2-CIMA).

Changes in the perception of life

The survivors experienced changes in their perception of life due to having suffered a disease that made them feel the fragility of the body and the probability of near death. This experience led them to recognize that the most valuable thing they possess is life. Having survived cancer gave them the possibility of a second birth, an opportunity to make changes and improve aspects that they consider negative or inadequate for survivorship.

I had the opportunity to be reborn. I am a reborn person, and when you are reborn, you change; you cannot continue being the same; it would be absurd. You change! You change the way you see life ... Being a patient was very hard for me. My condition got worse. I didn’t see the light, but I did see flashes. However, thanks to God, my wife, my optimism, my faith, and my colleagues, the treatment I received was successful in spite of all those ups and downs, and I made it through. Your life changes, but you also start to see it differently (E3-FEZU).

I went through all this to reach this point in which I feel a little recovered and at peace (E5-AMU).

Discussion

Surviving cancer implies that some time has passed since the stage of diagnosis and oncological treatment, that patients are in remission, and that they are considered free of the disease. Furthermore, it entails transformations that go beyond the physical or psychological sequelae that the cancer experience may cause. Surviving cancer is not synonymous with a life free of problems; on the contrary, there are multiple concerns related to the changes and effects generated by the disease and the treatment received. (18

The stigma of cancer in survivorship

This study shows how stigma was shaped through the physical and emotional marks left by the disease and treatment, as well as the labels assigned by people close to the patient, which reflect stigmatizing feelings and practices that are difficult to eliminate. Stigma has been studied mainly in the cancer experience associated with changes in physical appearance resulting from the disease itself and the side effects of treatment. 19-21 Regarding stigma in survivorship, in their study with adolescent cancer survivors, Ander et al. (6 indicate that this disease leaves its mark, but also remains hidden. They state that participants recognize that they are medically free of cancer, but they do not perceive themselves cancer-free; on the contrary, they express frustration at not being able to escape or erase the impact of cancer in their lives.

The participants in this study reported that one of their coping mechanisms for dealing with stigma was to begin the process of removing their marks by having others recognize that they still have abilities despite having had cancer. Other studies 22-24 mention the following coping strategies: avoiding talking about the experience, refusing to accept care from family members, claiming that they are well, trying to maintain a normal life, and avoiding certain people or situations that expose them to the reaction of others.

Survivorship support networks

This category showed how important support networks with family members and significant others are in terms of what they can provide to survivors and their influence on adaptation processes and the quality of life of cancer survivors. 25 Cancer survivors face different stressors and use available or newly developed resources to cope with stress; thus, social support is an interpersonal resource associated with improved psychological response.26

Participants’ accounts in this research allowed us to define two types of support: emotional and economic. Emotional support has been identified as a facilitator for the expression of feelings and fears, a means of overcoming anxiety and increasing confidence and self-esteem. It is also efficient in coping with stressful situations during survivorship. 27

Financial support includes the provision of monetary resources and elements required by survivors. This has been described as material or financial support. It is essential to reduce the economic burden experienced after the disease due to debts incurred during treatment, job loss, or anticipation of retirement, among other economic needs. 28

Self-care in survivorship

A responsible and conscious attitude of survivors favors their health and well-being through healthy behaviors related to nutrition, physical activity, and the avoidance of harmful substances. Patients become interested in following healthy habits during the treatment phase in order to ensure survival beyond cancer. As cancer survivors, they wish to maintain these healthy behaviors; however, they encounter some difficulties, for example, in maintaining the recommended physical activity because of the physical consequences of the disease itself or the treatments they have received. 29,30

Self-care also includes practices that favor emotional health such as self-forgiveness, self-healing, using free time for oneself, and maintaining an optimistic attitude. The latter has also been described as an intrapersonal resource necessary to maintain mental health. (31

Transcendence

Transcendence emerged as the final category of cancer survivorship. It is described as the result of the personal experience lived in the face of a disease that led patients to feel vulnerable and close to the possibility of losing their lives, thus making them recognize that life is the most valuable thing that human beings possess. Regarding the vulnerability experienced by survivors, cancer implies living with the mantle of death. Inevitably, this generates existential reflections that transform the person who experiences them. 32 In addition, this state of vulnerability gives rise to a transformation process based on a renewed value of life due to the confrontation of finitude and natural fragility with the assigned appreciation. 33

The nursing theory of self-transcendence proposes that facing a state of vulnerability develops the capacity to expand one’s limits in relation to others, to oneself, and to a spiritual and temporal dimension. All these aspects are compatible with the transformations described by the participants in this study. 34

Similarly, survivorship allows patients to reflect on what they have experienced and learned, which leads them to place greater value on life and health. As a result, they reorganize their activities, appreciate family spaces that were previously unnoticed, and dedicate more time to self-care. 35) This subsequent assessment is part of the coping process and leads to gains. Drury et al. 29 consider that the identity of individuals transcends that of patients, and thus they give it a unique meaning which is attributed only by them and for them.

The disease brought them moments of deep relationship with God and hope in Him and in His action so that everything will be all right in the end. 36 This research showed that participants also found strength in their beliefs during the disease and chose to maintain them during survivorship to face new challenges and find the desired balance in their lives.

Moreover, it is necessary to mention that participants describe that their reflections as survivors allow them to take stock of the influence of this experience in their lives, recognizing both negative and positive aspects. As mentioned in the description of categories, the positive aspects are perceived as beneficial because they contributed to their personal growth. This aspect in cancer survivorship generates post-traumatic growth as a way of finding positive elements in different aspects of life, even in the midst of adversity and vulnerability of the human being. This process has been associated with the search for meaning for oneself from the events of the past, the success of coping, and the encounter with transcendence. 32,37

Conclusions

Surviving cancer involves dealing with stigma not only because of the diagnosis itself, but also because of the fact of being a survivor. Coping with this situation requires building support networks both within the family and with significant others. Cancer survivors shift their health care towards a more holistic perspective, including the emotional dimension, as it represents another form of well-being and connection with their body and the cancer experience. Reinterpreting the new life based on reflection and belief in God is an inherent task in the story of survival, since nothing is ever the same again and everything becomes more meaningful and essential.

For the nursing practice, the results of this research allowed us to identify different needs that underlie cancer survivorship and that are currently unmet. Moreover, these results support the creation of chronicity-based survivorship programs that can accompany survivors for the rest of their life and respond to needs derived from the consequences of cancer and its treatments and to the specific challenges of survivorship. Finally, these results contribute to the conceptualization and understanding of cancer survivorship from the individuals’ own experience, by revealing the characteristics of their situation, the changes in different spheres, and the meanings they give to their life after this event.

The lack of more studies on survivorship conducted in Latin America and Colombia to better understand it in this context is a limitation of this research. Likewise, our reduced experience in the care of cancer survivors is considered a limitation, which could have influenced the interpretation of the participants’ accounts.

REFERENCES

1. Torre L, Siegel R, Ward E, Jemal A. Global Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends-An Update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):16-27. Available from: https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/25/1/16/157144/Global-Cancer-Incidence-and-Mortality-Rates-and [ Links ]

2. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Estimation and provision of global cancer indicators descriptive epidemiological cancer research. World Health Organization, IARC; 2020. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/ [ Links ]

3. Siegel R, Miller K, Fuchs H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;(1):7-33. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21708 [ Links ]

4. Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, Rowland JH. Going Beyond Being Lost in Transition: A Decade of Progress in Cancer Survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1978-1981. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1373 [ Links ]

5. Shin H, Bartlett R, De Gagne JC. Health-Related Quality of Life Among Survivors of Cancer in Adolescence: An Integrative Literature Review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;44:97-106. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.11.009 [ Links ]

6. Ander M, Cederberg JT, Von Essen L, Hovén E. Exploration of psychological distress experienced by survivors of adolescent cancer reporting a need for psychological support. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):1-17. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195899 [ Links ]

7. Davis C, Tami P, Ramsay D, Melanson L, MacLean L, Nersesian S, et al. Body image in older breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2020;29:823-832. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195899 [ Links ]

8. Milgrom Z, Severance T, Scanlon C, Carson A, Janota A, Vik T, et al. A evaluation of an extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) intervention in cancer prevention and survivorship care. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2022;22:135. DOI: 10.1186/s12911-022-01874-x [ Links ]

9. Valle C, Padilla N, Gellin M, Manning M, Reuland D, Rios P, et al. ¿Ahora qué?: Cultural adaptation of a cancer survivorship intervention for Latino/a cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28:1854-1861. DOI: 10.1002/pon.5164 [ Links ]

10. Zhao Y, Brettle A, Qiu L. The effectiveness of shared care in cancer survivor-A systematic review. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(4):1-17. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.3954 [ Links ]

11. Miranda S, Ortiz J. Los paradigmas de la investigación: un acercamiento teórico para reflexionar desde el campo de la investigación educativa. Ride. 2020;11(21):1-18. DOI: 10.23913/ride.v11i21.717 [ Links ]

12. Landín M, Sánchez S. El método biográfico narrativo. Una herramienta para la investigación educativa. Educación. 2019;28(54):227-242. DOI: 10.18800/educacion.201901.011 [ Links ]

13. Ortega J. ¿Cómo saturamos los datos? Una propuesta analítica “desde” y “para” la investigación cualitativa. Interciencia. 2020;45(6). Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/339/33963459007/html/ [ Links ]

14. Parra J. El arte del muestreo cualitativo y su importancia para la evaluación y la investigación de políticas públicas: una aproximación realista. Opera. 2019;25:119-136. DOI: 10.18601/16578651.n25.07 [ Links ]

15. De la Cuesta C. La reflexividad: un asunto crítico en la investigación cualitativa. Enfermería clínica. 2011;21(3):163-167. DOI: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2011.02.005 [ Links ]

16. Tinto J. El análisis de contenido como herramienta de utilidad para la realización de una investigación descriptiva. Un ejemplo de aplicación práctica utilizado para conocer las investigaciones realizadas sobre la imagen de marca de España y el efecto país de origen. Provincia. 2013;29:135-173. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/555/55530465007.pdf [ Links ]

17. Cancio I, Soares J. Criterios e estrategias de qualidade e rigor na pesquisa qualitativa. Ciencia y enfermería. 2020;26:28. DOI: 10.29393/CE26-22CEIS20022 [ Links ]

18. Chan R, Andi O, Yates P, Emery J, Jefford M, Koczwara B, et al. Outcomes of cancer survivorship education and training for primary care providers: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16:279-302. DOI: 10.1007/s11764-021-01018-6 [ Links ]

19. Adams RN, Mosher CE, Cohee AA, Stump TE, Monahan PO, Sledge GW, et al. Avoidant coping and self-efficacy mediate relationships between perceived social constraints and symptoms among long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2017;26(7):982-90. DOI: 10.1002/pon.4119 [ Links ]

20. Drury A, Payne S, Brady AM. Cancer survivorship: Advancing the concept in the context of colorectal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;29:135-47. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.06.006 [ Links ]

21. Hebdon M, Foli K, McComb S. Survivor in the cancer context: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(8):1774-86. DOI: 10.1111/jan.12646 [ Links ]

22. Gupta A, Dhillon PK, Govil J, Bumb D, Dey S, Krishnan S. Multiple stakeholder perspectives on cancer stigma in North India. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(14):6141-7. DOI: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.14.6141 [ Links ]

23. Ernst J, Mehnert A, Dietz A, Hornemann B, Esser P. Perceived stigmatization and its impact on quality of life - results from a large register-based study including breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):1-8. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-017-3742-2 [ Links ]

24. Oystacher T, Blasco D, He E, Huang D, Schear R, McGoldrick D, et al. Understanding stigma as a barrier to accessing cancer treatment in South Africa: Implications for public health campaigns. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;29:1-12. DOI: 10.11604/pamj.2018.29.73.14399 [ Links ]

25. Valeta M, Maza L, Bula J, Becerra E, Díaz S. Abrazando mi historia de vida: la experiencia de vivir con cáncer siendo adolescente. Revista Avances en Salud. 2018;2(2):12-20. DOI: 10.21897/25394622.145 [ Links ]

26. Garland E, Thielking P, Thomas E, Coombs M, White S, Lombardi J, et al. Linking dispositional mindfulness and positive psychological processes in cancer survivorship: a multivariate path analytic test of the mindfulness-to-meaning theory. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26:686-692. DOI: 10.21897/25394622.145 [ Links ]

27. Kamen C, Mustian KM, Heckler C, Janelsins MC, Peppone LJ, Mohile S, et al. The association between partner support and psychological distress among prostate cancer survivors in a nationwide study. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(3):492-9. DOI: 10.1007/s11764-015-0425-3 [ Links ]

28. Lopes M, Nascimento LC, Fontão Zago MM. Paradox of life among survivors of bladder cancer and treatments. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2016;50(2):222-229. DOI: 10.1590/S0080-623420160000200007 [ Links ]

29. Drury A, Payne S, Brady A. Cancer survivorship: Advancing the concept in the context of colorectal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;29:135-147. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.06.006 [ Links ]

30. Ochoa E, Carrillo GM, Sanabria D. Finding myself as a cervical cancer survivor: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;41:143-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.06.008 [ Links ]

31. Sira N, Lamson A, Foster CL. Relational and Spiritual Coping Among Emerging and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J Holist Nurs. 2020;38(1):52-67. DOI: 10.1177/0898010119874983 [ Links ]

32. Nadia C, Sharp J, Stafford L, Schofield P. Posttraumatic growth as a buffer and a vulnerability for psychological distress in mothers who are breast cancer survivor. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;275:31-37. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.013 [ Links ]

33. Santos J, Fontao M. Masculinities of prostate cancer survivors : a qualitative metasynthesis. Rev Bras Enferm. 2019;72(1):231-40. DOI: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0730 [ Links ]

34. Díaz L, Rodríguez L. Análisis y evaluación de la Teoría de Auto-trascendencia. Index Enferm. 2021;30(1-2). Available from: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962021000100017 [ Links ]

35. Chung M, Lin H. Fear of cancer recurrence, supportive care needs, and the utilization of psychosocial services in cancer survivors: A cross-sectional survey in Hong Kong. Psycho-Oncology. 2021;30:602-613. DOI: 10.1002/pon.5609 [ Links ]

36. Knaul F, Doubova S, González M, Durstine A, Pages G, Casanova F, et al. Self-identity, lived experiences, and challenges of breast, cervical, and prostate cancer survivorship in Mexico: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:577. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-020-07076-w [ Links ]

37. Liu Z, Doege D, Thong M, Arndt V. The relationship between posttraumatic growth and health-related quality of life in adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;276(1):159-168. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.044 [ Links ]

How to cite: Bermúdez Niño Y, Osorio Castaño JH. Surviving Cancer: Narratives of a Group of People’s Experiences. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2022;11(2):e2792. DOI: 10.22235/ech.v11i2.2792

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. Y. B. N. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; J. H. O. C. in a, c, d, e.

Received: January 18, 2022; Accepted: August 22, 2022

texto en

texto en