Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.11 no.1 Montevideo June 2022 Epub June 01, 2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v11i1.2615

Original articles

Representations and perspectives of primary caregivers of children with chronic kidney disease

1 Clínica Alemana Temuco, Chile

2 Universidad de La Frontera, Chile

3 Universidad Santo Tomás, Chile

Introduction:

Pediatric chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a serious health problem that affects the life of the adults and generates psychosocial impact on the family network.

Objective:

To reveal the representations and perspectives of primary caregivers of children with chronic kidney disease.

Methodology:

Study with phenomenological design administered in 9 informants, collection of information through in-depth interviews, category analysis, triangulation by researcher, safeguarding the rigorous criteria of Guba and Lincoln, and respect for the ethical principles of Ezekiel Emanuel.

Results:

The meta categories “living the disease”, “highly demanding disease” and “support networks present” emerged.

Discussion:

Coping with the disease is threatened by physical fatigue, uncertainty, and alteration of support within and outside the family structure. A similar result is found in the base study. The management of the child is carried out by the mother in almost all the activities associated with its treatment.

Conclusions:

Women provide care invisibly and continuously. It is necessary to make it visible as a social problem, to establish policies with a gender perspective that determine corrections of inequities that cultural stereotypes provide, as well as to make visible the need for greater nursing intervention as support for informal care.

Keywords: child care; chronic kidney failure; parents; gender identity

Introducción:

La enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) pediátrica es un problema de salud grave, que repercute en la vida de adulto y genera impacto psicosocial en la red familiar.

Objetivo:

Develar las representaciones y perspectivas de los cuidadores principales de hijos con enfermedad renal crónica.

Metodología:

Estudio con diseño fenomenológico administrado en 9 informantes, recolección de la información a través de entrevistas en profundidad, análisis de categorías, triangulación por investigador, resguardo de criterios de rigor de Guba y Lincoln, y respeto de los principios éticos de Ezekiel Emanuel.

Resultados:

Emergieron las metacategorías “viviendo la enfermedad”, “enfermedad altamente demandante” y “redes de apoyo presentes”.

Discusión:

El afrontamiento hacia la enfermedad se ve amenazado por el cansancio físico, incertidumbre y alteración del apoyo dentro y fuera de la estructura familiar; similar resultado se encuentra en el estudio base. El manejo del niño lo realiza la madre en casi la totalidad de las actividades asociadas al tratamiento.

Conclusiones:

La mujer proporciona cuidados en forma invisible y continua. Es necesario que se visibilice como problemática social, se establezcan políticas con enfoque de género que determinen correcciones de inequidades que proporcionan los estereotipos culturales, al igual que se visibilice la necesidad de una mayor intervención de enfermería como apoyo al cuidado informal.

Palabras clave: cuidado del niño; insuficiencia renal crónica; padres; identidad de género.

Introdução:

A doença renal crônica infantil (DRC) é um grave problema de saúde que afeta a vida adulta e gera impacto psicossocial na rede familiar.

Objetivo:

Desvelar as representações e perspectivas de cuidadores primários de filhos com doença renal crônica.

Metodologia:

Estudo com desenho fenomenológico aplicado em 9 informantes, coleta de informações por meio de entrevistas em profundidade, análise de categorias, triangulação por pesquisador, resguardando os rigorosos critérios de Guba e Lincoln, e respeito aos princípios éticos de Ezekiel Emanuel.

Resultados:

Emergiram as metacategorias “vivendo a doença”, “doença muito exigente” e “redes de apoio presentes”.

Discussão:

O enfrentamento da doença é ameaçado pelo cansaço físico, incerteza e alteração do suporte dentro e fora da estrutura familiar, resultado semelhante é encontrado no estudo de base. O manejo da criança é realizado pela mãe em quase as atividades associadas ao tratamento desta

Conclusões:

As mulheres prestam cuidados de forma invisível e contínua. É necessário torná-la visível como problema social, estabelecer políticas com perspectiva de gênero que determinem correções das iniquidades que os estereótipos culturais proporcionam, bem como tornar visível a necessidade de maior intervenção da enfermagem como suporte para o cuidado informal.

Palavras-chave: cuidado da criança; insuficiência renal crônica; pais; identidade de gênero

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health issue due to its epidemic nature and devastating complications. (1) There is little information about CKD in children, and its incidence may be underestimated due to difficulty in diagnosing it in the early stages of life. In Europe the pediatric incidence is around 11-12 per million population (ppmp) and for stages 3-5 the prevalence is 55-60 ppmp. (2-4 Other authors report a prevalence between 59-74 per million population and the Spanish Pediatric Registry of non-terminal CKD (REPIR II) reveals a prevalence greater than 128 per million population. 5,6 This significant increase is due to the improvement in treatments. 7 Also, it stands out that the disease is more frequent in boys 5,6) and that new medical therapies and dialysis have enabled better management and prognosis; however, preventing delayed growth, anemia, changes in mineral metabolism, and other issues have not yet been achieved, maintaining unacceptable rates of morbimortality. 8

More than 500 million people have chronic renal insufficiency, and approximately 10 % are over 20 years and 5 % are below that age. 9,10 CKD is one of the main causes of death in the industrialized world, (2,11 including the child population. The mortality rate in the pediatric population with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is from one to three per million.12-15

In addition, specialists recommend substitute treatment as the most suitable and kidney transplant from a living donor as the best therapeutic option, avoiding dialysis and providing a good quality of life. (6 If the transplant from a living donor cannot be done, peritoneal dialysis is the alternative. In Spain, it is the most common initial treatment in children under 6 years and a third of all minors under 18. 6

On the other hand, in medical treatment, gene therapy combined with recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO) of short, medium and prolonged half-life, VitD or calcitriol, intestinal phosphate binders, calcimimetics, and growth hormone (GH), is considered highly favorable during the period on dialysis. 16

For children with kidney disease, advances in purifying techniques and kidney transplant have increased survival; in this respect, it is recommended that nurses who provide care to pediatric kidney patients must be permanently updated on knowledge about renal replacement therapy. 17

In this life context, parents must add new tasks for managing the child, since CKD is a continuum of severity, 18 causing dependency on the parents or caregivers and health care team.

The decision was made to conduct this study given the paucity of publications on children with CKD. Most studies have been conducted on adolescents or adult patients who began with the disease in childhood; thus, the research question arises: What are the representations and perspectives of parents with children with stages IV and V chronic kidney disease in two hospitals of high complexity? And the objective of the study: To reveal the representations and perspectives of parents with children with chronic kidney disease in two hospitals of high complexity (Metropolitan and South Araucanía Regions) of Chile.

Methodology

Study with a phenomenological design that endeavors to understand the meaning of the experience and to generate knowledge of the social processes. As a philosophical methodological reference, social theory is used in the interpretative and comprehensive perspective of the everyday world of the parents and caregivers. 19 The inclusion criteria for the minors were: being to one of the two health institutions; being between 8 and 12 years old, to have a minimum of 6 months of evolution from the diagnosis of chronic renal disease in stage IV and V, and for the parents or caregivers: agree to grant a recorded interview, after signing informed consent. Three informants fulfilled the criteria in the hospital in Santiago, and 6 fulfilled the criteria and participated in the hospital in La Araucanía, totaling 9 informants.

The data collection was formalized through in-depth interviews, which were recorded and transcribed textually by the researchers themselves and the information was analyzed immediately, until reaching saturation, i.e., until no new data was collected, since, in the analysis of these data, redundancy was evident. From the information provided, the analysis codes and categories were determined, selecting the significant texts based on a thematic criterion, in search of expressions referring to the parents’ representations and expectations. There were no fathers in the interviews.

Triangulation by investigator was also developed, so that the principal investigator and both coinvestigators performed the analysis independently, later sharing the results. Differences were found, and a re-reading and new analysis were performed to finally reach a consensus. Thus, metacategories and intermediate categories emerge.

The analysis was supported by the ATLAS.ti version 9. Authorization was obtained from the Research and Teaching Unit of both hospitals, authorization from the Ethics Committee of the Araucanía Sur Health Service and informed consent from the adult. The seven ethical requirements of Ezekiel Emanuel (20, 21) were considered, as were the aspects included in the CIOMS 2002: value; scientific validity; fair participant selection; favorable risk-benefit ratio; independent review; informed consent; and respect for participants. The strict criteria included Guba and Lincoln’s dependency, credibility, auditability, and transferability. 22

Results

Biosociodemographic profile

The age of the mothers or caregivers ranged between 33 and 56 years, with 41±7.94 years. As a family group, nuclear families were made up of 3 to 7 members, with a mean and SD of 4 ±1.14. Family income was $330,000 ±232,501.

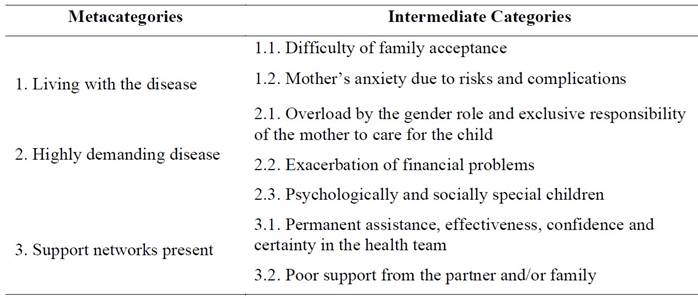

From the interviews with the children’s main caregivers, the following metacategories and intermediate categories emerged (Table 1).

Table 1: Representations and perspectives of mothers of children (8-12 years) with CKD

Source: Own elaboration (2019)

In the metacategory living with the disease, the intermediate categories difficulty of acceptance and mother’s anxiety due to complications emerged. In the first, the mothers indicate their concern and fear due to risks and complications of the disease of their child at the beginning, then they learn to live with it.

It was very difficult; he went from the respirator to being in bed and the doctor said that he had to be hooked up to dialysis. (E2) It was hard for me to accept it, it was difficult, but over time I learned that she had to go ahead with it and to try to help her as much as possible. (E4) When she started on dialysis it made the times difficult for me in the house, to dedicate to her, to see to her treatment and her medicines on time. (E5)

In the intermediate category mother’s anxiety due to risks and complications, the mothers indicate daily fear in relation to the severity or acquisition of some other acute ailment, which means decompensation of their basic disease and hospitalization for management and stabilization, which has repercussions for the family socially and economically.

It’s complicated, like a crossroads, if this month he’s going to pass from III to IV (in relation to creatinine and renal function)… that has been very depressing, he’s gaining weight!, he’s losing weight!, it has been distressing. (E1) I have been on medical leave for two years due to my son’s health problems. (E9) I believe in God, I have been struggling, until he gives me my son back, because I still have faith, but it’s been very difficult… (E6) I cannot go to training because what if something happens to my daughter? and with everything we’ve been through, one little thing means hospitalization, time off work, uh!! (E7)

In the metacategory highly demanding disease, these intermediate categories arose: overload by the gender role and exclusive responsibility of the mother for the care of the child, exacerbation of economic problems and psychologically and socially special children.

Overload by the gender role and exclusive responsibility of the mother for the care of the child refers to the social construction that attributes men and women with different characteristics according to their biological sex. In this case, the role is described that women assume according to social mandates. The accounts expose how the woman is allocated the role of protective mother, being the person in charge of the child’s care, their therapies, and delegating the father to the role of family provider. Consequently, an erosion of the gender role is observed, in its identity and femininity, abandoning the role of wife/partner to be the working mother, administrator and emotional support of the home.

My life revolves around him, all day, I am always with him, at night, I hook him up and everything, I don’t dare leave him alone. (E8) Dad is the provider. (E2) I say, nothing is going to happen to me because I’m strong, but I suddenly feel overwhelmed. (E1) I don’t go out with friends, my husband does, I practically have no time for anything! (E9) He supports me, but it’s different, for example, we had an appointment with the speech therapist yesterday and he didn’t take him, I did, even though I’m running late, I go. (E1) My life revolves around him, all day, in the morning disconnecting, school, I worry about my stuff, the house, then I go to pick him up from school. Suddenly they call me that he doesn’t feel well, and I run to pick him up from school to see what’s wrong and take him to emergency. (E4)

With respect to the exclusive responsibility of the mother, they state that the child’s life and that of the main caregiver revolves around the disease, in their treatment, activities and routines, with restrictions in the caregiver’s personal and social activities (going out with friends, sharing with the family, and even not being concerned about their own health), to prioritize the child’s care, causing frustration and social isolation. The child is always the priority, even leaving other children, partner, friends and family aside.

Moreover, they are afraid to delegate or to give another person the responsibility of the child’s care due to the risks, possible complications, and treatment errors. They feel essential to the child’s treatment and care, which implies overload and family isolation.

Suddenly I get tired, I get exhausted, I have tendonitis in my arm. (…) My other daughter is a little delayed. (E4) I don’t trust my husband, that’s the truth, I feel like, if I’m not there, things aren’t going to work well, so, to have it right, I prefer to be there, I don’t know until when! (E3) It scares me to delegate because we have our routine. (E9) Now I had to go to training, but I didn’t go, who gives him medications, who hooks him up, I have help, but the trust isn’t there. (E5)

In exacerbation of economic problems, the main caregiver stops working, causing the family financial hardship and less purchasing power, with the greatest economic impact being at the time of the diagnosis. In some cases, the child accompanies the main caregiver to sporadic jobs, so that the family can generate financial support.

The bank didn’t wait for us to pay them and foreclosed on the house, these have been difficult processes, nobody understands the other side. (E8) We have stopped working, because to travel to the hospital every day, we were traveling from Melipilla to see him here in the ICU. (E4) In the summer, I work, I take her to work and look after her at the same time. (E5)

In psychologically and socially special children, the main caregivers describe the children as mature for their age and state that they are responsible for their therapy. They are limited in the social and recreational activities for their age, such as sharing with other children, playing outside, doing sports, and sharing foods at school.

It is worth noting that the mother backs down in terms of the responsibilities the child must fulfill according to their process of development and growth, such as helping in chores around the house, school attendance, doing homework, and others, deemed measures of protection for the child. They reiterate admiration for the children, for the behavior toward their condition, at the same time some mothers consider them more life companions rather than a child.

He didn’t have a childhood, he matured very fast, he doesn’t have a life like the other kids, he cries and suffers because at 6 or 7 in the evening I have to hook him up and take him to the hospital and all the other kids are playing outside and he’s inside, especially when it’s hot. (…) When he goes to a party at school, I make him what can eat and don’t ask for anything else, he is very responsible, if he is ill, he takes his medication, respects his diet without salt, low in potassium, he doesn’t eat more cookies than what I tell him, he doesn’t take more without asking. (E1) There are no obligations for the girl, sometimes she gets hooked up a little bit later, she stays in, I go early, I am there waiting for my kids, like I’m the principal, then I leave my kids working and I go quietly to get her, take her to school, we live close, if she needs anything (…) They are different children, and they start off so small, it’s part of their routine…, it is more difficult for one that is older (…) She’s been always a good classmate (in everything) yes. (E5)

The metacategory support networks present contains the categories permanent assistance, effectiveness, confidence, and certainty in the health team; and poor support from the partner and/or family. In the first, the mothers refer to the mutual understanding fostered with the health team in talking about family topics and feeling supported and guided, since they also refer to the certainty that they generate in caring for the child.

At first, we clashed with the nurse, but now no, I learned that they are helping me, that if it weren’t for them my daughter would not be how she is, they guided me about what I had to do. (E4)

The mothers recount that, in the face of the difficulties with the treatment, the health team help them in finding a solution and always responding, at any time, which is strongly related to the confidence and certainty they feel in them. In addition, they train them in the therapy they must continue at home with their children, with the mothers feeling competent to do this in their home, as well as other activities or techniques complementary to the treatment.

When the power goes out, I immediately call the nurse and she explain to me what I have to do… They have helped me a lot… (E3) I have learned to give injections, to give him hormones even epo (erythropoietin). (E4) The nurse has taught to us well; we’ve had good teacher! (E2)

In the intermediate category support of the partner/family, despite there being families who refer to not feeling supported by their partner and/or family, the mothers recount feeling supported by their partner and their closest relatives, which is not necessarily associated with their understanding and the support the caregivers refer to needing.

They’ve supported me in everything so far. (E3) Yes, he always supports me. Always. (E2) Always together even when we weren’t getting along, we are even separated (yes, but only recently), yes, just two years, and we carry on regardless. (E7)

Discussion

The metacategory living with the disease contains the intermediate categories difficulty of family acceptance and maternal anxiety due to risks and complications. First, it is important to say that coping with the disease generates in the parents the need for training on the management of the child, but over time it is observed that only the mother performs almost all the activities associated with the treatment of this disease. 23

In risks and complications, the evidence shows that the survival of children with CKD has increased remarkably, due to new treatments and technology even though the first years after diagnosis pose a serious problem due to the difficulties of maintaining good biological control, affecting the emotional, cognitive, physical, and social areas, which alters their quality of life throughout their growth and development. 17 All these factors affect the family, a result like the baseline study.

In the metacategory highly demanding disease and the intermediate categories it is the woman in the gender role, who assumes a role of protective mother of the child and person in charge of the care, with a great erosion of the identity role of woman and in her relationship as a couple. This generates a feeling of loneliness, loss of affection, communication, and support with their partner. 24 In our study similarities in gender roles are reported.

Another responsibility of the mother is their children’s learning process. It has been demonstrated in this respect that children on hemodialysis have low learning and school attendance due to the long hours of treatment sessions. In the learning process, a strongly affected domain is physical activity, affecting their quality of life. One study shows that 54 % of patients on hemodialysis perceive their quality of life as good compared to 53 % of patients with peritoneal dialysis. 25

Altogether, in the first school years, children with CKD seem to feel a greater social acceptance, recommending, for optimal care, a quality-of-life assessment to help promote the pediatric patient’s health. 26

Although they are special children, one study, (27 showed academic performance below 34% and found no relation with the medical variables of CKD. Mathematics had the lowest distribution of performance scores. In univariate models, the low performance was significantly related to the days of school absence (p = 0.006) and the presence of an individualized education plan (p <0.0001). 27

Economically, the asymmetry between the productive and reproductive economy, the distribution of responsibilities in the home, the woman’s responsibility in ensuring the family’s health, and the man contributing economically to the household is known, and it stands out that it is the mother who assumes all the care of the child.

In support networks present and intermediate categories, on the topic of social support, the parents do not participate in ecclesiastical, governmental or community organizations, among others, but they stress the ongoing support of the health team, especially responding to the child’s physiological, social, psychological, and pedagogical needs, emphasizing the trust in the child and their family, the different times of health-disease.

Another aspect to consider is that the mothers recount feeling competent and trained by the health personnel in the treatment of their child, receiving training from the beginning of the disease in the pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of their child, which reaffirms the certainty, but at the same time a high demand in terms of therapy and organization of daily routines.

Finally, recovering the value aspect of the nurse’s role as a guarantor of rights employed in protecting the rights of the children, and the professionals who work with vulnerable populations. On the matter of nursing, the legal framework must be discussed to assess the principles of human rights, and the legal framework of protections in pediatric health. They are suggested to monitor the rights, concentrate on development indicators and on the objectives of sustainable development, considering the auditing of rights as a tool to increase the fulfillment of children’s rights and their quality of life. 28

Conclusions

In representations and perspectives, this study is a contribution, as there are no national studies that show the reality of mothers with children with CKD aged 8 to 12 years, and that show the reality of a hospital in a capital city and one in a region.

A distinguishing element is gender role, since it is the woman who provides care invisibly and continuously. This transfer of responsibilities of health care from the state to the family requires changes; it must be highlighted as a social problem, so gender-focused policies can be established that determine corrections in the inequities, that provide cultural stereotypes, and make the need for greater nursing intervention visible as a support for informal care.

The results denote the need for public policies that generate programs, strategies and actions that offer greater support to families, such as social, psychological, economic support, and that consist of therapists and social services consulting. Thus, the children and their families would be supported not only in their process of growth and development, but also in improvements in their life expectancies.

The authors consider the development of such strategies fundamental, prioritizing health care, such as having a nurse specializing in dialysis, that will have to perform on the three levels of care, in the follow-up and continuous assessment of these children, and who will encourage the children to enroll in Primary Care for their check-ups.

Another aspect is participation in the organization of the network: the children must be active in the network, assigned to primary care, and in continuous follow-up. Primary health care is very useful, as it provides support in clinical decision-making and could contribute to improving the health team-patient relationship by making participation in the choice of the most beneficial option possible. This way, the necessary tools are provided so the patient can enjoy adulthood with a satisfactory quality of life and the promotion of their skills is supported to achieve their maximum potential biologically, psychologically, and socially in such a way that they can prolong their active and productive life to the full.

Pediatric nephrologists must be part of the support network, aware that the complications in pediatric CKD will have consequences in adulthood. And they must understand the unique characteristics that CKD presents in children to significantly improve patient care, in short, to tend toward developing a comprehensive view of their patients.

From nursing and the care of the mother and family, work must be done to broaden the knowledge and skills of the parents and/or caregivers to confront and strengthen the process, strategies for relaxation and continuous psychological support must be recommended for managing stress, organizing time, and protection support.

One limitation is the paucity of publications about representations of the parents of children with CKD, especially in Latin America since most of the studies describe the situation of adult patients. Another limitation was the ability to access a hospital in the capital that concentrates children with the diagnoses in this study, which is why the investigator had to make several trips from the south of Chile, incurring greater time involvement.

REFERENCES

1. Flores JC, Alvo M, Borja H, Morales J, Vega J, Zúñiga C, et al. Enfermedad renal crónica: Clasificación, identificación, manejo y complicaciones. Rev. méd. Chile (Internet). 2009 Ene (citado 2021 Dic 07);137(1):137-177. DOI: 10.4067/S0034-98872009000100026 [ Links ]

2. Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012 Mar;27(3):363-73. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-011-1939-1. [ Links ]

3. ESPN/ERA Registry (Internet). European Registry for Children on Renal Replacement Therapy; 2021. Disponible en www.espn-reg.org/index.jsp [ Links ]

4. Wong CJ, Moxey-Mims M, Jerry-Fluker J, Warady BA, Furth SL. CKiD (CKD in children) prospective cohort study: a review of current findings. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(6):1002-11. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.018 [ Links ]

5. Wedekin M, Ehrich JH, Offner G, Pape L. Renal replacement therapy in infants with chronic renal failure in the first year of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:18-23. [ Links ]

6. Asociación Española de Pediatría (Internet). Protocolos diagnósticos y terapéuticos en Nefrología Pediátrica Asociación Española de Nefrología Pediátrica; 2014. Disponible en https://www.aeped.es/protocolos/ [ Links ]

7. Baum M. Overview of chronic kidney disease in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(2):158-60. DOI: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833695cb [ Links ]

8. Cano Sch F, Rojo LA, Ceballos OML. Enfermedad renal crónica en pediatría y nuevos marcadores moleculares. Rev. chil. Pediatra. 2012 Abr (citado 2021 Dic 07); 83(2):117-127. DOI: 10.4067/S0370-41062012000200002 [ Links ]

9. López MM. Enfermedad renal crónica pediátrica (Internet). Slideshare.net. (citado el 30 de julio de 2021). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://es.slideshare.net/MML93/enfermedad-renal-crnica-pediatrica [ Links ]

10. Martínez-Castelao A, Górriz-Teruel J, Bover-Sanjuán J, Segura-de la Morena J, Cebollada J, Escalada J, et al. Documento de consenso para la detección y manejo de la enfermedad renal crónica. Nefrología. 2014 (citado el 30 de julio de 2021);34(2):0-272. DOI:10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2014.Feb.12455 [ Links ]

11. Montell Hernández OA, Vidal Tallet A, Sánchez Hernández C, Méndez Dayout A, Delgado Fernández M del R, Bolaños Drake FM. Enfermedad renal crónica no terminal en los pacientes en edad pediátrica ingresados y seguidos en consulta de Nefrología. Rev médica electrón. 2013;35(1):1-10. [ Links ]

12. Song R, Yosypiv IV. Genetics of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26(3):353-64. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-010-1629-4. [ Links ]

13. García Ramírez M, García Martínez E. Afectación renal en las enfermedades sistémicas. Protoc Diagn Per Pediatr. 2014;(1):333-53. [ Links ]

14. Saura Hernández M del C, Brito Machado E, Duménigo Lugo D, Viera Pérez I, González Ojeda GR. Malformaciones renales y del tracto urinario con daño renal en Pediatría. Rev. Cubana Pediatr. 2015;87(1):40-9. [ Links ]

15. Asociación Española de Nefrología Pediátrica. Nefrología pediátrica: manual práctico. Madrid: Médica Panamericana; 2011. [ Links ]

16. Rees L, Mak R. Nutrition and growth in children with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:615-23. [ Links ]

17. Andreu Periz D, Sarria JA. Actualidad del Tratamiento Renal Sustitutivo Pediátrico. Enferm Nefrol (Internet). 2017 Jun (citado 2021 Dic 08); 20(2):179-183. DOI: 10.4321/s2254-288420170000200011. [ Links ]

18. KDIGO. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Supl. 2012;2:139-274 [ Links ]

19. Schütz, A. Estudios sobre teoría social. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu; 1974. [ Links ]

20. Emanuel E. ¿Qué hace que la investigación clínica sea ética? Siete requisitos éticos. En Lolas F, Quezada A, editores. Pautas éticas de investigación en sujetos humanos: nuevas perspectivas Santiago de Chile: Programa Regional de Bioética OPS/OMS; 2003, p. 83-96. [ Links ]

21. Rodríguez Yunta E. Comités DE evaluación ética y científica para la investigación en Seres humanos y Las pautas CIOMS 2002. Acta Bioeth. 2004;10(1):37-48. [ Links ]

22. Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research. En Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editores. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks:Sage; 1994, p. 105-117. [ Links ]

23. Uribe Meneses A. Características familiares en situación de enfermedad crónica. Respuestas. 2014;19(1):6-12. [ Links ]

24. Arias Flores E. La rabia de siete a ocho: Un acercamiento semiótico a La familia de Nuni Sarmiento. Logos. 2018;28(2):337-45. Disponible en: https://www.readcube.com/articles/10.15443%2Frl2825 [ Links ]

25. Crasborn A. Calidad de vida en niños y adolescentes con enfermedad renal crónica terminal. Fundación para el niño enfermo renal (Fundanier) , Guatemala, julio 2018 (Tesis de grado). Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar; 2018. Disponible en: http://recursosbiblio.url.edu.gt/tesiseortiz/2018/09/18/Crasborn-Andrea.pdf [ Links ]

26. Dotis, J, Pavlaki, A, Printza, N, Stabouli, S, Antoniou, S, Gkogka, C, et al. Quality of life in children with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(12):2309-16. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-016-3457-7 [ Links ]

27. Harshman, LA, Johnson, RJ, Matheson, MB, Kogon, AJ, Shinnar, S, Gerson, AC, et al. Academic achievement in children with chronic kidney disease: a report from the CKiD cohort. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(4):689-96. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-018-4144-7 [ Links ]

28. O’Hare, BA-M, Devakumar, D, Allen, S. Using international human rights law to improve child health in low-income countries: a framework for healthcare professionals. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16(1):11. DOI: 10.1186/s12914-016-0083-1 [ Links ]

Nota: Publication generated in the Master Program in Public Health, Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile. Research conducted without financial support

2How to cite: Lagos Antonietti K, Rivas Riveros E, Sepúlveda Rivas C. Representations and perspectives of primary caregivers of children with chronic kidney disease. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2022;11(1), e2615. DOI: 10.22235/ech.v11i1.2615

Contribution of the authors: a) Study conception and design, b) Data acquisition, c) Data analysis and interpretation, d) Writing of the manuscript, e) Critical review of the manuscript. K. L. A. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; E. R. R. in c, d, e; C. S. R. in c, d, e.

Received: June 25, 2021; Accepted: March 28, 2022

text in

text in