Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.10 no.2 Montevideo 2021 Epub Dec 01, 2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v10i2.2410

Original articles

Transcend the Death of Child with Cancer: Professional Health Experiences

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, pvegav@uc.cl

2 Universidad Andrés Bello, Chile

3 Complejo Asistencial Dr. Sotero del Río, Chile

4 Complejo Asistencial Dr. Sotero del Río, Chile

5 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

6 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

Objective:

To reveal the perception of grief support of professionals in pediatric oncology units, after the death of the patients.

Method:

Qualitative phenomenological study. 22 in-depth interviews were conducted with professionals from 5 pediatric oncology units of public hospitals in Santiago. Once the narratives were transcribed, the comprehensive analysis and subsequent triangulation of the data was performed, achieving saturation.

Results:

Professionals perceive themselves supported in their grief by being able to experience the losses in a protected environment and feeling supported by their surroundings. They recognized the existence of external and internal factors that facilitated the process of grief. However, this support is perceived as insufficient, as there is a lack of formal support from the institution, as well as a protected grief period, or support from mental health professionals to the teams. All death experiences allow professionals to transcend their pain based on lifelong learning and to give meaning to their work.

Conclusion:

Grief support felt by the professionals is generated from their own initiatives of re-encounter within the teams, which is insufficient. Therefore, training in coping with death is necessary from undergraduate level, which would allow greater cohesiveness in coping and greater self-care within the teams.

Keywords: social support; grief; health professionals; oncology; child.

Objetivo:

Develar la percepción del apoyo en duelo de los profesionales de las unidades de oncología pediátrica, tras el fallecimiento de los pacientes.

Método:

Estudio fenomenológico cualitativo. Se realizaron 22 entrevistas en profundidad a profesionales de 5 unidades de oncología pediátrica de hospitales públicos de Santiago de Chile. Una vez transcritas las narraciones, se realizó el análisis comprensivo y posteriormente la triangulación de los datos, hasta lograr su saturación.

Resultados:

Los profesionales se perciben apoyados en su duelo al poder experimentar las pérdidas en un ambiente protegido y sentirse apoyados por su entorno. Reconocen la existencia de factores externos e internos que facilitan el proceso de duelo. Sin embargo, este apoyo se percibe como insuficiente, ya que falta un apoyo formal por parte de la institución, así como un periodo de duelo protegido, o el apoyo de los profesionales de la salud mental a los equipos. Todas las experiencias de muerte permiten a los profesionales trascender su dolor a partir del aprendizaje permanente y dar sentido a su trabajo.

Conclusión:

El apoyo en duelo que sienten los profesionales se genera a partir de sus propias iniciativas de reencuentro dentro de los equipos, lo cual es insuficiente. Por ello, es necesaria la formación en el afrontamiento de la muerte desde el pregrado, lo que permitiría una mayor cohesión en el afrontamiento y un mayor autocuidado dentro de los equipos.

Palabras clave: apoyo social; duelo; profesionales de la salud; oncología; niño.

Objetivo:

Desvelar a percepção do apoio ao luto dos profissionais das unidades de oncologia pediátrica, após o óbito dos pacientes.

Método:

Estudo fenomenológico qualitativo. Foram realizadas vinte e duas entrevistas aprofundadas com profissionais de cinco unidades de oncologia pediátrica de hospitais públicos de Santiago. Uma vez transcritas as narrativas, realizou-se à análise compreensiva e posteriormente à triangulação dos dados, alcançando a saturação destes.

Resultados:

Os profissionais percebem-se amparados em seu luto, pois podem vivenciar perdas em um ambiente protegido e sentir-se amparados por seu ambiente. Eles reconhecem a existência de fatores externos e internos que facilitam o processo de luto. Contudo, este apoio é percebido como insuficiente, visto que falta um apoio formal da instituição, bem como um período de luto protegido, ou o apoio dos profissionais de saúde mental para as equipes. Todas as experiências de morte permitem aos profissionais transcender sua dor por meio da aprendizagem ao longo da vida e dar sentido ao seu trabalho.

Conclusão:

O apoio no luto, sentido pelos profissionais, é gerado a partir das suas próprias iniciativas de reencontro com as equipes, o que é insuficiente. Portanto, o treinamento no enfrentamento da morte desde a graduação faz-se necessário, o que possibilitaria maior coesão no enfrentamento e maior autocuidado dentro das equipes.

Palavras-chave: apoio social; luto; profissionais de saúde; oncologia; criança

Introduction

Since the 20th century, modern medicine has experienced great technological advances that have allowed a paradigm shift in relation to the ultimate goal of this discipline; curing diseases and prolonging life, which has led to a focus on the number of years of life rather than the quality of life during those years. 1 From this, a progressive increase in the distancing of health professionals with death has been observed in the West, giving it a negative connotation and transforming it into a “taboo” subject. 2 This situation occurs especially in pediatric teams, who show difficulty in addressing, understanding, and accepting the death of a patient. 3

Cancer in children under 14 years of age accounts for 1.06 % of all cancers diagnosed worldwide. According to figures provided by the World Health Organisation (WHO), more than 27,000 cases of cancer are diagnosed annually in children under 14 years of age in the Americas, and of these, approximately 45% die, making cancer the second leading cause of death in this age group. In Chile, the incidence of cancer in children under 15 is 12.5 per 100,000 children, with approximately 540 new cases diagnosed each year, and a mortality rate of 2.5 per 100,000. 4,5

Death is therefore a reality that is faced by teams caring for children with cancer, so it is a situation that can be conceived as a failure in the workplace or as the loss of someone significant. 3,6 It is this sense of loss and the perception of delivery of less-effective care or attention, which can generate impotence, suffering, anger, sadness, and insecurity, 7 leading the professional to greater emotional exhaustion. 8,9 This adds to the appearance of physical health problems such as headaches, excessive nervousness, abdominal disorders, and disturbances in sleep, which translates into a decrease in the quality of care, job dissatisfaction and greater absenteeism.9 For some participants, this problem responds both to a lack of professional training in the areas of palliative care and grief support (11,12 as well as to the inadequate support that exists from the health institutions themselves, to the health teams in the process of coping with the loss of patients. 12,13

In the case of pediatric oncology care, it should be taken into account that the treatments are prolonged and have many side effects for patients, requiring a growing demand for care, to which organizational factors are added such as fatigue due to lack of personnel, communication deficit, surrogate decision making, role conflicts and insufficient vacation time. 11

In contrast to the above, some nursing studies have revealed that the death of a patient can also generate positive attitudes, which are related to the satisfaction generated by providing quality care to people at the end of life, which is considered rewarding and a learning situation, reducing the risk of emotional fatigue and with it, Burnout Syndrome. 14,15 Following what has been described, several studies have indicated that social support to health professionals can be an important mediator in facing the death of patients, especially in the area of child healthcare. 16,17) However, this support should not only be mediated by the recognition of the emotional tie to the patient, but by the possibility of expressing the pain of the loss and feeling real support that responds to expectations and needs.18

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to reveal what it means for health professionals working in a pediatric oncology unit to feel supported in grief after the death of a patient and to identify the favoring and hindering factors in the grief process.

Method

This research was conducted under the constructivist paradigm, based on Husserl's descriptive phenomenology. 19 This emphasizes describing the experience that becomes conscious through the subject's discourse, and thus reaching the essence of the experiences in the most original way possible.20,21 In the case of this research, the perception of feeling supported in professional grief.

Participants

The study sample was by convenience. University and technical professionals working in pediatric oncology units of five public hospitals in Santiago, Chile, were invited to participate. These were contacted between the months of May and September 2017. Among the inclusion criteria were: Having worked for more than a year in the unit, having witnessed the death of patients, to acknowledge having had professional grief and, having expressed their participation voluntarily. All workers with recent personal grief were excluded.

Procedures

The professionals were invited by email, and those who agreed to participate were contacted by the researchers to attend the interview and take informed consent. The technique used to generate and analyze the data was according to the ten stages described by Helen Streubert, 22 based on Husserl’ philosophy.

This began with the bracketing of each of the project researchers. Each interviewer met with one of the participants in a private place. Prior to starting the interview, a consent was read and signed.

Measure/script/data gathering technique

The data was collected through in-depth audio recorded interviews, carried out by 4 of the researchers trained for this purpose, who shared a unified script whose pinnacle question was: How have you experienced the grief support received, after the death of patients in your unit? On average, the interviews lasted 45 minutes, and field notes were taken during these meetings. All the narratives were transcribed literally.

Data analysis

The comprehensive analysis process was carried out through several readings of the narratives that allowed to “dwell with the data”.24 Subsequently, meetings were held between the researchers to triangulate the data revealed and thus reach consensus on the basis of similar units of meaning, considering the same environment and period. The essence of the phenomenon was structured once data saturation was reached. To confirm the findings, these were shared with the participants, who stated that they felt recognized with the units of meaning. During the process, compliance with the methodological rigor proposed by Guba & Lincoln was ensured,23)in terms of credibility, confirmability, dependability and transferability.

During the research, compliance with ethical requirements was ensured according to Emanuel.24 Additionally, it was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee, MEDUC (N° 16-329) and funded by the National Health Research Fund (FONIS-SA16 I0189).

Results

Participant characteristics

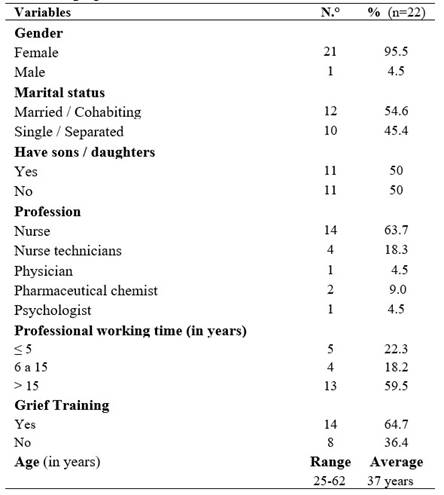

In the present study 22 professionals and health technicians participated, who through their narratives shared their experiences. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Findings

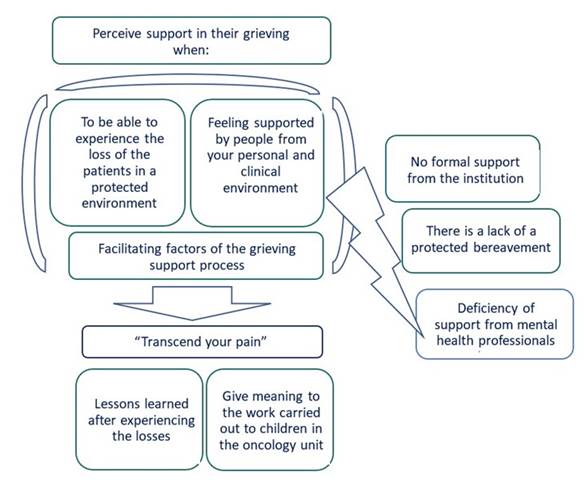

Based on the accounts provided by the participants, it was revealed that the pediatric oncology professionals and technicians perceive support in their grieving when they are able to experience the loss of patients in a protected environment and feel supported by people around them. In turn, they recognize that there are external and internal factors that facilitate the process of dealing with grief within the teams. However, this support is perceived as insufficient, given that there is no formal support from the institution; there is a lack of a protected grief period and deficiency of support from mental health professionals to the teams.

All the experiences described above, help professionals to transcend their pain based on lifelong learning and achieve to give meaning to their daily work.

Next, each of the units of meaning revealed will be analyzed (Figure 1).

To be able to experience the loss of the patients in a protected environment

The professionals who work in pediatric oncology, express that they can experience their grief, due to the death of their patients, thanks to the fact that they felt free to create their own parting rites and had the possibility of participating in funerals, which favors closure in the loss process.

Actually, all in the team recognize our grief… In the unit, when a child dies, we get together with the people on the team who were there at that minute; speak what they thought… We have the opportunity to express and say what we feel outwardly and… It doesn't matter if he is a doctor, if he is whoever he is! In that part, it's like a horizontal thing. We are all the same in that minute! (Nurse, 43 years)

When the girl died, I had the need to do a ritual and invited the rest of the team, because it was also the need for all the team, and there I took a little plant and said, "Let's plant this little plant that our patient represents." And they all came! So, it was an individual need that became a team need. ... And the one that was a ritual not only personal, but as a team, it contains a lot of me and the team... it´s like closing a cycle. (Psychologist, 30 years)

Feeling supported by people from your personal and clinical environment

Participants consider that they have received support within their own team, and support from their family and friends, which has allowed them to share their experiences of loss. The possibility of speaking and expressing their emotions makes them feel understood and recognized in their relationship with the patients, thus being able to freely express their sorrow.

We support each other. During my shift (a child) dies ... Therefore, we are all there, supporting each other while attending. Because of the sadness, one starts to cry. So, like we feel supported…. the conversation between us is absolutely spontaneous, it comes naturally from within. (Nurse, 52 years)

I feel that my friends, my family, are a super empathic environment and that I can discuss these issues with them. With my partner, especially. I think that for me this has been fundamental. It bothers me a little if I transfer this from work to home, but I feel that I am a nurse, but I am also a person. In the end, even if you deny it, it still affects your daily life. And when I have shared it, for me it has been more relieved than saving it. (Nurse, 25 years)

Facilitating factors of the grieving support process

Professionals recognize that there are external and internal factors that facilitate the grieving process. Among the externals is having a cohesive team, good communication between colleagues, preparation for death, activities as a team outside the workplace and support from a mentor.

It is they (the team) who help you live the loss of patients. For me, without a team I would not work here ... I´m very sensitive, so if a colleague is able to hug, to look at you, to say, "How are you?". That is more than enough for me! Therefore, this gives me the confidence to show my vulnerability... Something has happened with the team that has matured a lot, and now when one is not able to attend… they don't. Now “I can't” is not frowned upon. (Psycho-oncologist, 30 years)

All the strategies have helped me to feel supported by the rest of the team: the times we have to talk, to take care of each other, the walks, the dinners, the affection, the self-care evenings. I think that everything as a whole has helped me to cope well… At the beginning, I received support from my boss and also from my colleagues... from who we were at the time. That's why I try, with the newer girls, to be there if they need anything. Because these are difficult moments, whether one has a close bond or not, it is difficult... to manage the family or whatever has to be done at that moment, one does not have experience in the usual way of being there. (Nurse, 36 years)

In turn, the internal factors experienced by professionals is self-care in the face of grief and the search for spiritual support.

Because when one comes out into reality that is something else, it is a materialistic world ... So, those of us who live here and know that children are struggling to live… I believe that this has helped me to grow spiritually. To empathize, to look where the rest do not. And being the person that I´m, I believe that… thanks to this I´m the person that I’m. (Nursing technician, 37 years)

Support in professional grief is perceived as insufficient

Although oncology professionals feel supported in their grief, they say that this support could be of better quality and timelier, especially when it comes from the institution's authorities. In addition, they experience lack of a protected grief period to develop closure rituals with all patients and, lack of formal psychological interventions to the team, which allows for the development of adequate emotional accompaniment.

That management come and ask, how are we? … No, never! I've never felt it, I don't know if it touched me… let it be talked about! Let the supervising nurse ask us ... "how was it, what happened and ..." ¡No, never! They are more practical things, but not in relation to how one feels. (Nurse, 33 years)

I have felt supported, not many times… independently that there is a psychologist here, but they are for the children… So, sometimes I feel that there should be more support, such as a psychologist to guide us on how to deal with that situation. But I still feel, I need to vent with whom? ... because I feel that sometimes we feel the same: we feel sorry, the suffering, the loss, the way it left ... “why they (children) suffer so much? why do they have to suffer so much, why so much pain, why the wait so long?” Things that remain ... and we do not have a psychologist to support us. (Nursing technician, 52 years)

Transcend your pain

All the experiences described above, allow professionals to transcend their pain in facing loss of a patient that was significant to them, based on lifelong learning and they achieve to give meaning to the work done on a daily basis, both to their patients and to the families; even providing support to their own colleagues within the health team.

I feel that… I feel that deep down over the years, it´s not that you end up harder but that it costs you a bit... It costs you a little to connect with the problems, as well as the basic ones of others ... Deep down, with everything that you are learning, as I feel that in your life you become much less serious ... You learn to live a much happier life because you will realize that your life has no problems ... And unfortunately, you learn it through the death of child. (Nurse, 23 years)

Then over time you learn… and I have learned… Every day here you are learning something… the value of life. I do a lot of things here and I try to help in whatever I can… I work for the children! And… yes, I try to give as much as I can. (Nursing Technician, 52 years)

Lessons learned after experiencing the losses

The experiences surrounding the death of children in the unit are considered by professionals as an education that allows them to improve professional care based on the experiences of loss and in turn, understand that death is part of life.

I have also learned love. The love to one of these patients, leads you to continue functioning. Because one might have lost a patient, because they died ... but there are another thirty who are there, who are still smiling. So those same smiles, those same children, help you overcome your sorrows. So, I think that love… that is the motivation, and it is what helps the most to overcome it. (Nurse, 34 years)

There are children who die, and it makes you feel more sadness, and then there are others whose death give relief, in the sense that they have now gone to rest. It is like one care more about the child ... in giving him care with dignity, that he is clean ... if he is bleeding, stop the bleeding and try to help him. (Nurse, 33 years)

Give meaning to the work carried out to children in the oncology unit

For the participants, the grieving process within the team allows them to give meaning to the work done for the children in the oncology unit, through the assessment of their own devotion to duty and being able to see life from another perspective.

I am captivated by what I do. When you love something, you commit ... I really like what I do and I think it gives me a lot back. I think it is a privilege, and that is what we try to convey to our children too ... that gives me a sense of transcendence through what I give! I think that through the lives of those children that we save. (Hematologist-oncologist, 52 years)

But the truth is that… you did your job the best you could… and I am very much at peace because I do my job at 100% and I give 120%... the place where I have had more satisfaction, both personal and professional, in spite of how painful it can be, is oncology. (Nurse specialist, 42 years)

Discussion

This study revealed that the professionals of pediatric oncology units agree and express that they experience grief with the death of patients, experiencing feelings of regret and loss. The place where the participants say to find the support to transcend and work through the grief process, is in their same unit of work. In this, they share rituals of closure in a protected environment and with people who are meaningful to them. In this regard, several studies indicate that the development of this type of ritual inside the teams is a revealing instance, which allows professionals to feel involved and contained in their grief.25,26 Rituals would be activities that favor satisfaction within a positive work environment, encouraging the perception of a collective effort and, recognition of the work done. 27 These closures or farewells allow for coping with feelings of disappointment, grief, anguish, and failure after a death,28,29 especially when the professional prepares for this.2 Some of these aspects are part of the stories expressed by the participants.

It is relevant that the support of significant persons in the environment is considered, in several investigations, as one of the main strategies used by health professionals, as a protective factor against emotional burnout,26,30 generating greater satisfaction for compassion. 25 As in the present study, Forster 31 and Papadotau,7 revealed that peer support provides a positive validation within spaces of reflection in their practice, improving self-confidence and job satisfaction. Also, the family of the professional can fulfil an important role of containment of the suffering; a partner being the one who usually provides the most support, 31,32 and help in the face of work stress. 33

Regarding the factors considered as facilitators of professional grief, this study revealed that effective communication, monitoring of the team and co-participation in decision making, provides the foundations for teamwork where the emotional expression of the loss is facilitated, as other investigations refer to.18,34,35However, these elements within the teams must be motivated and framed in a joint venture with the authorities of the institutions, 12,30 situation perceived by the participants of this study as one of the weaknesses of the process.

On the other hand, self-care and active work on the losses experienced in the workplace and personal environments, promotes self-reflection and acceptance in the professionals and thus recognize death as something natural, 36) which was narrated by some of the participants. In this sense, the accompaniment of a mentor, who guides and supports those who have less experience in the area, generates confidence, security, and emotional containment, which is key in the first experiences of death. 27,28

Another of the facilitating factors mentioned by the participants is spiritual support, which allows them to reconsider the experiences of loss, reassess the assumptions about the world, the purpose of life and develop compassion,18,30,31 and with it, be able to more effectively deal with end-of-life patient care. 26,37

Despite all the above, grief support within some teams is perceived as insufficient, given the low perception in recognition of professional losses by the institution's authorities, and with it, the perception of minor support in situations of loss,38,39as stated also by professionals in this study. Therefore, they expect from the authorities the creation of formal interventions to strengthen and develop coping strategies, as well as specialized psychological care in relation to grief.18,31,38 To this is added the lack of protected periods to develop end-of-life care, which is hindered by obstacles in the work environment and organizational aspects that threaten the possibility of facilitating a dignified death for patients and families.36In addition, the lack of greater communication between the different levels worsens collaborative work, given by vertical dynamics and where nurses assume a passive role in decision-making.34,40

It is important to note that the experiences described by the study participants, allowed them to recognize that what they lived helped them transcend their pain and transform it into a life learning experience, which favored becoming aware of the relevance of getting involved with a substantial other,26,34 through a greater commitment and compassionate relationship in their work,9 which for some oncology nurses would be "loving care-giving". 14 For some researchers, the coping with death generates a deep existential reflection in professionals, which helps to find meaning in the face of their experiences of loss, cultivating their spirituality based on their values and belief.28,31

Clinical implications

The grief support received by pediatric oncology unit professionals is generated from their own initiatives of re-encounter within the teams, especially those that count with the creation and development of rites of closure within the unit, which are described as "Sacred Pause". 25 This has allowed for a significant parting to be had with both the patient and the family. This re-encounter necessitates the formation of cohesive and close teams, with respectful, inclusive, effective and trustworthy communication, where the vulnerable professional feels protected and free to express their emotions and opinions.

It should not be forgotten that professionals of pediatric oncology units demand the spaces and times to provide patient-centered care, from a compassionate, comprehensive and humanized approach, especially when in an end-of-life process. To respond to these demands, the active participation of the authorities of the institutions is required, who must provide psychological support and continuous training in this type of thematic, in particular to teams that are exposed to loss of patients.

This study revealed that the confrontation of the duel is being carried out within the teams, without adequate supervision of the institutions. It should be they and the authorities who must ensure the creation of policies within the units, where accompaniment and mental health support programs should be developed for workers, which would help in their self-care and thus prevent compassion fatigue or early detection of personnel who are at risk of burnout.

On the other hand, this research, together with the studies found, showed that this issue has not yet been fully addressed. There are many gaps between what the teams experience and the understanding of how they face it personally and collectively, which should be developed in future research to know what the long-term effects are against the perception of loss by professionals, and what the consequences may be in the care and attention provided.

Study limitations

The authors acknowledge that a limitation of this research was that a limited group of 22 professionals in the pediatric area belonging to 5 hospitals in the capital of Chile, which do not represent all the hospitals in the country. However, it corresponded to half of the centers dedicated to childhood oncology and the data saturation criterion was met.

Furthermore, another limitation was the low participation of men and physicians that could have affected the findings, which has been observed in other research about death.

Conclusion

This study describes the experience lives in depth by the professionals of pediatric oncology units, for those feel supported by their grief allows them to transcend the loss and give meaning to their work, favoring job satisfaction and self-perception.

For this reason, the incorporation of this thematic in the training of new professionals becomes relevant, integrating it in the curriculum of the different disciplines, and subsequently in continuous training. These strategies will allow early work on the theme of death; accept the right to mourning and acquire tools to deliver timely and high-quality care to patients and families in an end-of-life situation.

REFERENCES

1. Coca C, Arranaz P, Diéz-Asper H. Burn-out in the healthcare staff who care for children at the end of their lives and their families. In: Gómez Sancho M, editores. Palliative care in the child. Spain: Lerko/GAFOS;2007. [ Links ]

2. Chen C, Chow A, Tang S. Bereavement process of professional caregivers after deaths of their patients: A meta-ethnographic synthesis of qualitative studies and an integrated model. INT J NURS STUD. (Internet). 2018 (citado 2019 May 6);88:104-113. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.010 [ Links ]

3. Crowe S, Sullivant S, Miller-Smith L, Lantos J. Grief and Burnout in the PICU. Pediatrics. (Internet). 2017 (citado 2019 Jul 2019);139(5):e20164041. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-4041 [ Links ]

4. Internacional Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer today (Internet). France: World Health Organization. C2020-2021. (citado 2021 May 25). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://gco.iarc.fr/today [ Links ]

5. Vallebuona C. Primer informe del Registro Nacional de Cáncer Infantil de Chile (menores de 15 años), RENSI. (Internet). Santiago, MINSAL;2018. Disponible en: http://www.ipsuss.cl/ipsuss/site/artic/20180117/asocfile/20180117150429/informe_renci_2007_2011registro_nacional_c__ncer_infantildepto_epidemiolog__aminsal2018.pdf [ Links ]

6. Ferreira A, Becker H, da Graça Corso M, Zanchi D. Palliative care in paediatric oncology: perceptions, expertise and practices from the perspective of the multidisciplinary team. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. (Internet). 2015 (citado 2019 May 6);36(2):56-62. DOI: 10.1590/1983-1447.2015.02.46299 [ Links ]

7. Papadatou D, Bellali T, Papazoglou I, Petraki D. Greek nurse and physician grief as a result of caring for children dying of cancer. Pediatric Nursing. (Internet). 2002 (citado 2018 Nov 15);28(4):345-353. PMID: 12226956. [ Links ]

8. Chew Y, Ang S, Shorey S. Experiences of new nurses dealing with death in a paediatric setting: A descriptive qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. (Internet). 2021 (citado 2021 May 22); (77): 343-354. DOI: 10.1111/jan.14602 [ Links ]

9. Vega P, González R, Santibáñez N, Ferrada C, Spicto J, Sateler A, Bustos J. Supporting in grief and burnout of the nursing team from pediatric units in Chilean hospitals. Rev Esc Enferm. USP (Internet) 2018 (citado 2019 May 6);51(2):1-6. DOI: 10.1590/s1980-220x2017004303289. [ Links ]

10. Laor-Maayany R, Goldzweig G, Hasson-Ohayon I, Bar-Sela G, Engler-Gross A, Braun M. Compassion fatigue among oncologists: the role of grief, sense of failure, and exposure to suffering and death. Supportive Care in Cancer. (Internet) 2020 (citado 2021 May 22);1528:2025-2031. DOI: 10.1007/s00520-019-05009-3 [ Links ]

11. Santos A, Santos M. Stress and Burnout at Work in Pediatric Oncology: Integrative Literature Review. Psicol. cienc. prof. (Internet). 2015 (citado 2018 Nov 15);35(2):437-456. DOI: 10.1590/1982-370300462014 [ Links ]

12. Vega P, González R, López ME, Abarca E, Carrasco P, Rojo L, González X. Perception of support in professional’s and technician’s grief of pediatric intensive care units in public hospitals. Rev Chil Pediatr. (Internet). 2019 (citado 2020 May 9);90(4):429-436. DOI: 10.32641/rchped.v90i4.1010 [ Links ]

13. Medland J, Howard-Ruben J, Whitaker E. Fostering psychosocial wellness in oncology nurses: addressing burnout and social support in the workplace. Oncol Nurs Forum. (Internet). 2004 (citado 2018 Nov 15);31(1):47-54. DOI: 10.1188/04.ONF.47-54. PMID: 14722587. [ Links ]

14. Vega P, González R, Palma C, Oyarzun C, Ahumada E, Mandiola J, Rivera M. Revealing the meaning of the grieving process in pediatric nurses who face the death of a patient due to cancer. AQUICHAN. (Internet). 2013 (citado 2018 Nov 15);13(1):81-91. DOI: 10.4067/S0370-41062017000500007 [ Links ]

15. Fernández M, García M, Pérez M, Cruz F. Experiences, and obstacles of psychologists in the accompaniment of processes at the end of life. Annals of Psychology. (Internet). 2013 (citado 2018 Nov 15);16(1):1-8. DOI: 10.6018/analesps.29.1.139121 [ Links ]

16. Betriana F, Kongsuwan W. Nurses’ Grief in Caring for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Literature Review. Songklanagarind J Nurs. (Internet). 2019 (citado 2020 Jul 16);39(1):138-4. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/nur-psu/article/view/181323 [ Links ]

17. Anderson K, Ewen H, Miles E. The Grief support in Healthcare Scale. Nursing Research. (Internet) 2010 (citado 2018 Nov 16);59(6):372-379. DOI: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181fca9de [ Links ]

18. Wenzel J, Shaha M, Klimmek R, Krumm S. Working through grief and loss: oncology nurses' perspectives on professional bereavement. Oncol Nurs Forum. (Internet). 2011(citado 2018 Nov 16); 38(4): 272-282. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E272-E282 [ Links ]

19. Husserl E. Ideas related to pure phenomenology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. México: Fondo Cultural de Economía; 1947. [ Links ]

20. Barbera N, Iniciarte A. Fenomenología y Hermenéutica: dos perspectivas para estudiar las ciencias sociales y humanas. Multiciencias. 2012;12(2):199-205. Disponible en https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/904/90424216010.pdf [ Links ]

21. Waldenfels B. Fenomenología de la experiencia en Edmund Husserl. ÁRETE Revista de Filosofía. (Internet) 2017. (citado 2021 May 30);29(2):409-426. DOI: 10.18800/arete.201702.008 [ Links ]

22. Streubert H, Carpenter D. Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. 4a.ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2007. [ Links ]

23. Johnson S, Rasulova S. Qualitative research and the evaluation of development impact: incorporating authenticity into the assessment of rigour. J Dev Effect. (Internet). 2017 (citado 2021 May 30);9(2):263-76. DOI: 10.1080/19439342.2017.1306577 [ Links ]

24. Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. (Internet). 2000 (citado 2021 May 30);283(20):2701-2711. DOI: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. PMID: 10819955 [ Links ]

25. Kapoor S, Morgan CK, Siddique MA, Guntupalli KK. "Sacred Pause" in the ICU: Evaluation of a Ritual and Intervention to Lower Distress and Burnout. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (Internet). 2018 (citado 2020 May 3);35(10):1337-1341. DOI:10.1177/1049909118768247 [ Links ]

26. Montross-Thomas LP, Scheiber C, Meier EA, Irwin SA. Personally Meaningful Rituals: A Way to Increase Compassion and Decrease Burnout among Hospice Staff and Volunteers. J Palliat Med. (Internet). 2016 (citado 2020 May 3);19(10):1043-1050. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0294. PMID: 27337055 [ Links ]

27. Gerow L, Conejo P, Alonzo A, Davis N, Rodgers S, Domian EW. Creating a curtain of protection: nurses' experiences of grief following patient death. J Nurs Scholarsh. (Internet) 2010 (citado 2018 Nov 16);42(2):122-129. DOI:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01343.x [ Links ]

28. Arribas S, Jaureguizar J, Bernarás E. Satisfacción y fatiga por compasión en personal de enfermería de oncología: estudio descriptivo y correlacional. Enfermería Global. (Internet) 2020 (citado 2020 Dec 3);19,4:120-144. DOI: 10.6018/eglobal.417261. [ Links ]

29. Wentzel D, Brysiewicz P. Integrative review of facility interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. (Internet). 2017 (citado 2019 Jun 13);44(3):E124-E140. DOI: 10.1188/17.ONF.E124-E140. PMID: 28635987. [ Links ]

30. Granek L, Ariad S, Shapira S, Bar- Sela G, Ben-David M. Barriers and facilitators in coping with patient death in clinical oncology. Support Care Cancer. (Internet). 2016 (citado 2019 May 12);24(10):4219-4227. DOI: 10.1007/s00520-016-3249-4. [ Links ]

31. Forster E, Hafiz A. Pediatric death and dying: exploring coping strategies of health professionals and perceptions of support provision. Int J Palliat Nurs. (Internet) 2015 (citado 2018 May 22);21(6):294-301. DOI: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.6.294. PMID: 26126678. [ Links ]

32. Macedo A, Mercês NNA, Silva LAGP, et al. Nurses’ Coping Strategies in Pediatric Oncology: An Integrative Review. Rev Fund Care Online. (Internet). 2019 (citado 2020 May 22);11(3):718-724. DOI: 10.9789/2175-5361.2019.v11i3.718-724 [ Links ]

33. Sullivan CE, King AR, Holdiness J, Durrell J, Roberts KK, Spencer C, et al. Reducing Compassion Fatigue in Inpatient Pediatric Oncology Nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. (Internet). 2019 (citado 2020 May 22);46(3):338-347. DOI: 10.1188/19.ONF.338-347. PMID: 31007264. [ Links ]

34. Robson K, Williams C. Dealing with the death of a long-term patient; ¿what is the impact and how do podiatrists cope? Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. (Internet) 2017 (citado 2018 May 22);10:36. DOI: 10.1186/s13047-017-0219-0 [ Links ]

35. Zheng R, Lee SF, Bloomer MJ. How nurses cope with patient death: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs. (Internet) 2018 (citado 2019 Jul 2);27(1-2):e39-e49. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.13975. [ Links ]

36. González M, Gallego F, Vargas L, del Águila Hidalgo B, Alameda G, Luque C. The end of life in the Intensive Care Unit from the nurse perspective: a phenomenological study. Enfermería Intensiva. (Internet) 2011 (citado 2018 May 22);22(1):13-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.enfi.2010.11.003 [ Links ]

37. Peters L, Cant R, Payne S, O'Connor M, McDermott F, Hood K, Morphet J, Shimoinaba K. How death anxiety impacts nurses' caring for patients at the end of life: a review of literature. Open Nurs J. (Internet). 2013(citado 2018 May 22);7:14-21. DOI: 10.2174/1874434601307010014. [ Links ]

38. Kellogg MB, Barker M, McCune N. The lived experience of pediatric burn nurses following patient death. Pediatr Nurs. (Internet) 2014 Nov-Dec (citado 2018 May 22);40(6):297-301. PMID: 25929125. [ Links ]

39. Scaratti M, Oliveira DR, Rós ACR, et al. From Diagnosis to Terminal Illness: the Multiprofessional Team Endeavior in Pediatric Oncology. Rev Fund Care Online. (Internet) 2019 (citado 2018 May 22);11(n. esp):311-316. DOI: 10.9789/2175-5361.2019.v11i2.311-316 [ Links ]

40. Carnevale F, Farrell C, Cremer R, Canoui P, Séguret S, Gaudreault J, de Bérail B, Lacroix J, Leclerc F, Hubert P. Struggling to do what is right for the child: Pediatric life-support decisions among physicians and nurses in France and Quebec. Journal of Child Health Care. (Internet). 2012 (citado 2018 May 22);16(2):109-123. DOI: 10.1177/1367493511420184 [ Links ]

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank each of the health professionals in the area of childhood oncology who kindly shared their experiences.

How to cite: Vega Vega P, Carrasco Aldunate P, Rojo Suárez L, López Encina ME, González Rodríguez R, González Briones X. Transcend the Death of Child with Cancer: Professional Health Experiences. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2021;10(2):73-88. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v10i2.2410

Contribution of the authors: a) Study conception and design, b) Data acquisition, c) Data analysis and interpretation, d) Writing of the manuscript, e) Critical review of the manuscript. P. V. V has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; P. C. A. in b, c, d, e; L. R. S. in a, b, c, d, e; M. E. L. E. in a, b, c, d, e; R. G. R. in a, b, c, d; X. G. B. in b, c, d.

Received: December 22, 2020; Accepted: June 22, 2021

text in

text in