Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.10 no.2 Montevideo 2021 Epub 01-Dic-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v10i2.2422

Original Articles

Meaning of the Mother's Experience of Support during the Breastfeeding Process

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, pceballos@ucm.cl

Introduction:

It has been described that there are experiences in people's lives that have the capacity to modulate the nervous system, which directly influences human development. Timely intervention in early childhood has the potential to have a positive impact on their development. In this logic, breastfeeding takes on special importance, since it increases the probability of survival, provides adequate nutrition and stimulation, favors a safe environment, and is an immense contribution to the strengthening of social ties, among other benefits. The support the mother receives during the process is fundamental for successful breastfeeding.

Objective:

To unveil the meaning of the maternal experience on support during the breastfeeding process.

Methodology:

A phenomenological design study in which an analysis was carried out with secondary data, according to Edmund Husserl's perspective. To ensure the methodological rigor of this research, the criteria of Guba and Lincoln were applied. The ethical aspects of the research were approached from Ezekiel Emanuel's seven ethical requirements.

Results:

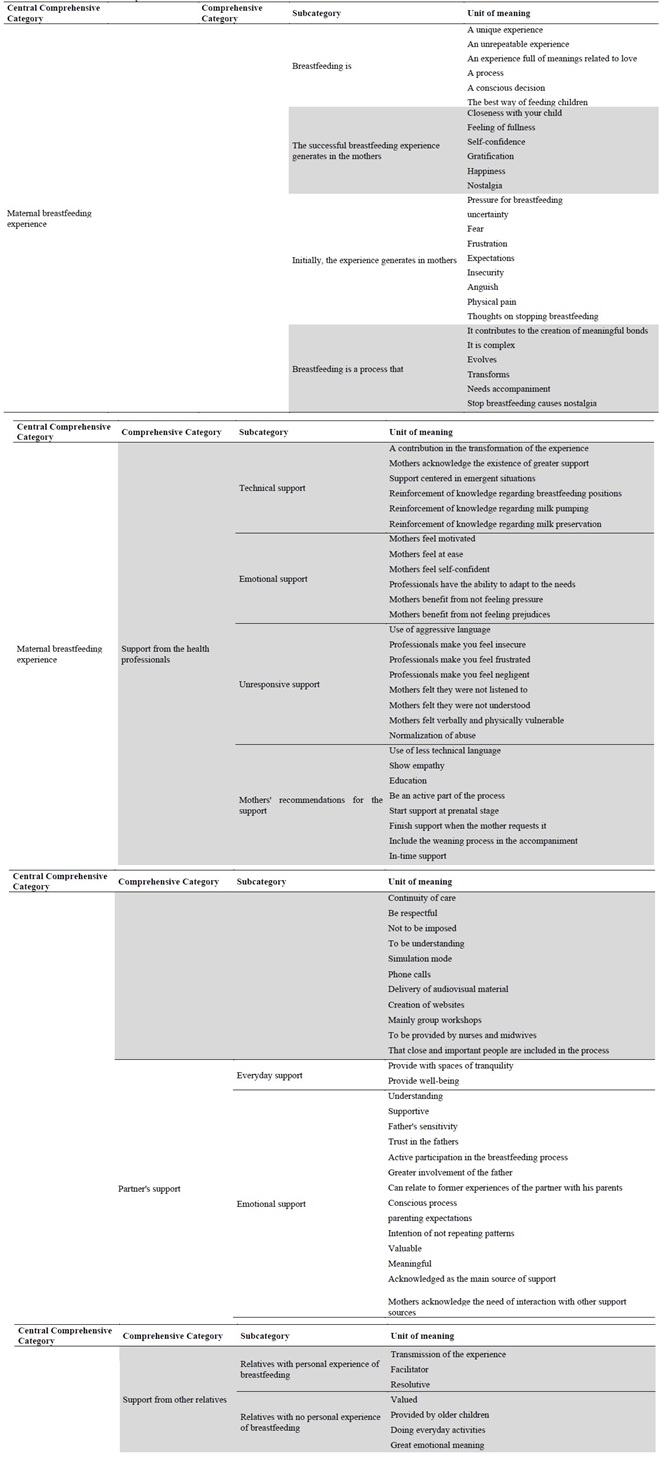

The meaning of the maternal experience of support during the breastfeeding process was unveiled in four comprehensive categories: maternal experience of breastfeeding, experience of support from health professionals, experience of support from partners, and experience of support from other family members.

Conclusions:

The three sources of support identified nurture and modulate the breastfeeding experience in a complementary manner, so that the indivisibility of the influences exerted by them is a constitutive characteristic for the support to be perceived by the mothers as comprehensive and supportive.

Keywords: breastfeeding; life-changing events; qualitative research; nursing care.

Introducción:

Se ha descrito la existencia de experiencias de la vida de las personas que tienen la capacidad de modular el sistema nervioso, lo que influye directamente en el desarrollo humano. Intervenir oportunamente en la primera infancia tiene el potencial de impactar positivamente en su desarrollo. En esta lógica, la lactancia materna cobra especial protagonismo, ya que aumenta la probabilidad de sobrevivir, brinda una nutrición y estimulación adecuada, favorece un entorno seguro, además de ser un inmenso aporte en el fortalecimiento de los lazos sociales, entre otros beneficios. El apoyo que reciba la madre durante el proceso es fundamental para lograr un amamantamiento exitoso.

Objetivo:

Develar el significado de la experiencia materna en torno al apoyo en el proceso de amamantamiento.

Metodología:

Estudio de diseño fenomenológico en el cual se realizó un análisis con datos secundarios, según la perspectiva de Edmund Husserl. Para asegurar el rigor metodológico de esta investigación se aplicaron los criterios de Guba y Lincoln. Los aspectos éticos de la investigación fueron abordados desde los siete requisitos éticos de Ezekiel Emanuel.

Resultados:

El significado de la experiencia materna en torno al apoyo en el proceso de amamantamiento se develó en cuatro categorías comprensivas: la experiencia materna de amamantamiento, experiencia de apoyo de los profesionales de la salud, experiencia de apoyo de la pareja y experiencia de apoyo de otros familiares.

Conclusiones:

Las tres fuentes de apoyo identificadas nutren y modulan la experiencia de amamantamiento de manera complementaria, por lo que la indivisibilidad de las influencias ejercidas por ellas es una característica constitutiva para que el apoyo sea percibido por las madres como comprensivo y contenedor.

Palabras clave: lactancia materna; acontecimientos que cambian la vida; investigación cualitativa; cuidado de enfermería.

Introdução:

Descreveu-se a existência de experiências de vida de pessoas que têm a capacidade de moldar o sistema nervoso, o que influencia diretamente no desenvolvimento humano. Intervir oportunamente na primeira infância tem o potencial de impactar positivamente no seu desenvolvimento. Seguindo esta lógica, o aleitamento materno ganha um protagonismo especial, já que aumenta a probabilidade de sobrevivência, oferece nutrição e estimulacão adequadas, favorece um ambiente seguro, além de ser uma imensa contribuição no fortalecimento de laços sociais, entre outros benefícios. O apoio que a mãe recebe durante o processo é fundamental para conseguir uma amamentação de sucesso.

Objetivo:

Revelar o significado da experiência materna ao redor do apoio no processo do aleitamento materno.

Metodologia:

Estudo do desenho fenomenológico, para o qual se realizou a análise com dados secundários, conforme a perspectiva de Edmund Husserl. Para garantir o rigor metodológico desta investigação foram aplicados os critérios de Guba e Lincoln. Os aspectos éticos da investigação foram abordados desde os sete requisitos éticos de Ezekiel Emanuel.

Resultados:

O significado da experiência materna ao redor do apoio no processo da amamentação foi dividido em quatro categorias compreensivas: a experiência materna do aleitamento, a experiência do apoio dos profissionais da saúde, a experiência do apoio do parceiro e a experiência do apoio de outros familiares.

Conclusões:

As três fontes de apoio identificadas nutrem e moldam a experiência do aleitamento de forma complementária. Por tanto, a indivisibilidade das influências que cada um destes atores exercem é uma característica constitutiva para que o apoio seja percebido pelas mães como compreensivo e acolhedor.

Palavras-chave: aleitamento materno; acontecimentos que causam mudanças de vida; investigação qualitativa; cuidado de enfermagem.

Introduction

The existence of experiences in people's lives has been described, that have the capacity to modulate the nervous system, allowing it to be more receptive and present great plasticity, such as nutrition, education and environments that provide responsible and loving care, which directly influence human development. 1,2

Human development is understood as a social process that involves biological, psychological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of life, aspects that make the interaction of people with society and the environment possible. Therefore, to intervene in human development, it is necessary to consider all the aspects involved in it. 1,2

Accordingly, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) points out that timely intervention in early childhood has the potential to offer children more opportunities in terms of access to education, quality of learning, growth, and health. Hence, interventions focused on childhood, especially in the early years of this stage, provide greater opportunities to reduce inequalities in human development. 3

It is in this logic that breastfeeding takes on special importance, since the evidence supports its impact on human development, pointing out that it increases the probability of survival, provides adequate nutrition and stimulation, favors a safe environment, and contributes to the strengthening of social ties, among other benefits. 4

The aforementioned is supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF that currently recommend that children should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, ideally from the first hour of life, and that complementary feeding should be continued for up to two years of age or beyond if the family so decides. 3

Considering this recommendation, WHO undertook to support countries in the implementation and follow-up of the "Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition", approved by member states in May 2002. The plan has six targets, one of which is to increase exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of age to at least 50 % by 2025. In 2018, WHO estimated that 33 countries met this target. However, it was estimated that 68 countries still have exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of life rates below 50 %. 5,6

Chile has joined this initiative by adopting policies that provide comprehensive protection for the development of children. Consequently, different strategies have been implemented to promote breastfeeding, including the "Mother and Child Friendly Hospital" initiative, the "Comprehensive Protection System for Early Childhood, Chile Grows with You", and the extension of parental postnatal leave from 12 to 24 weeks. Likewise, the initiative of breast milk banks was resumed, having currently one in the country. 7,8)

These strategies have been an effective support for breastfeeding, since according to the last national survey on breastfeeding in primary care (ENALMA by its Spanish acronym) carried out in 2013, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of life remained steady at 56.3 %. 9

Notwithstanding the compliance with the goal proposed by the WHO, it is worrisome that in 2016, the Chilean Department of Health Statistics and Information states that 73.5% of children on health control, receive exclusive breastfeeding at one month of life, which is the lowest figure since 1993. This highlights the importance of having comprehensive support in this period when breastfeeding is established, making clear the need for more research to deepen the characteristics of this support so that it is meaningful for mothers experiencing this process. 8-10

There are studies that conclude that when support is offered to breastfeeding women, the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding increases, as well as mentioning that this support can be provided by trained professionals during prenatal and postnatal care or it can be offered by non-professionals, including peers or a combination of both. Other studies are more categorical and point out that the support received by the mother during the process is fundamental to achieve successful breastfeeding. 11,12

Considering the background information presented, the objective of this research was to unveil the meaning of the maternal experience on support during the breastfeeding process and thus contribute to the optimization of nursing care in this process.

Methodology

The meaning of the maternal experience on professional support during the breastfeeding process was explored by means of a phenomenological design to understand the experience lived from the perspective of the mothers themselves. 13) Spiegelberg in 1975 pointed out that descriptive phenomenology stimulates the perception of the lived experience and implies the direct exploration, analysis, and description of the phenomena, as free as possible from presuppositions, with the aim that they purely represent the lived experience of the subject of study. (14

Regarding the theoretical-philosophical reference framework, this research was approached according to the perspective of Edmund Husserl, founder of phenomenology. This choice was based on the need to focus on the phenomenon itself and on the relevance of transmitting the experience lived by the participants, as it was perceived by them, which allowed access to the essence of the phenomenon. (13, 14)

This study was conducted with secondary data from the research "Perceptions of mothers and health professionals regarding the organization and care related to breastfeeding: context strengths and challenges at the primary level of care" (2017), which had the approval of the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, the Ethics Committee of the Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Sur Oriente de Santiago de Chile and the approval of the Medical Directors of the participating Family Health Centers (CESFAM by its Spanish acronym).

In the aforementioned study, the participants were women over 18 years of age, users of two CESFAMs in the southeastern sector of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, Chile, which correspond to the public health system of the country and who were experiencing breastfeeding during the first year of life of their child, primigravid or multiparous. In the case of multiparous women, women with or without previous breastfeeding experience were included. The exclusion criteria for this study were: maternal contraindication to breastfeeding or having had pre-term children, or with pathologies that interfere with the physiological establishment of BF, so it was a purposive sampling. 13,14

For the construction of the phenomenon of this research, we used the verbatim transcripts of ten interviews conducted in the primary study, which were recorded with the consent of the participants, and then transcribed and anonymized. The interviews conducted by the main researcher of the primary study and one of the co-researchers of the study provided the opportunity to describe in depth their experience and the meanings they attributed to it, in the light of the northern question: What has been your experience with support during your breastfeeding process? Subsequently, to deepen their understanding, they had a protocol of open questions, based on the evidence related to the support received in the breastfeeding process. 14

In the current research, the saturation of the units of meaning, which is the point where they began to repeat themselves, was reached with eight of the ten transcripts available for analysis. Likewise, the ten existing transcriptions were analyzed through Colaizzi's method. 14

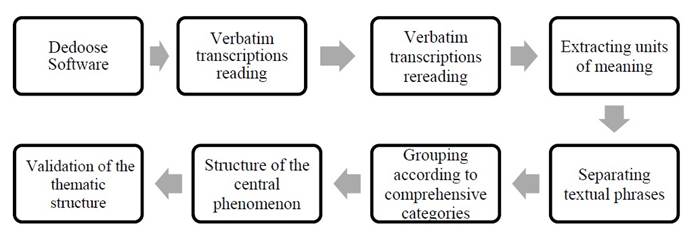

For the analysis of the study conducted by the main researcher, each of the transcripts of the in-depth interviews was read, then reread to extract the units of meaning, separating the textual phrases that contained them. Subsequently, the units of meaning were grouped into comprehensive categories, and then the structure of the central phenomenon was developed accordingly. The organization of the data was carried out with the support of the Dedoose software. Finally, the thematic structure was validated with the researcher who conducted the interviews, who also conducted the current research. (14

The methodological rigor of this research was ensured by applying three of Guba & Lincoln's four criteria, since, being a secondary data analysis, the description of the constructed phenomenon was not returned to the participants. To meet the criterion of confirmability of the study, an effort was made to make explicit the entire research process, which will allow other interested researchers to follow the route of what was done. Regarding fidelity, textual phrases from the mothers' narratives were used to represent the units of meaning that emerged, and the participants and their context were described to safeguard the transferability of the results. 14

The ethical aspects of the research, which was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on August 7, 2018, were addressed from the seven ethical requirements of Ezekiel Emanuel. 15). Figure 1

Results

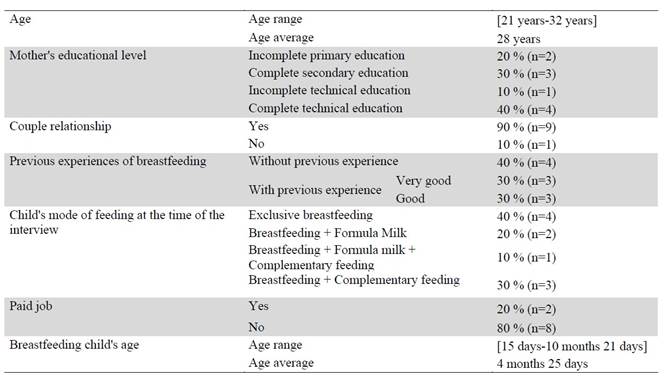

The sociodemographic and health characteristics of the ten participants and their children that were analyzed for this study are presented in Table 1.

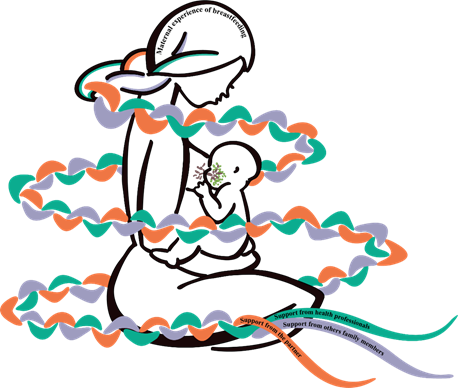

The current research sought to unveil the meaning of the maternal experience of support during the breastfeeding process, a phenomenon whose central comprehensive category was the "maternal breastfeeding experience", which was unveiled in three fundamental pillars of support: "support from health professionals", "support from the partner" and "support from other family members" (Figure 2).

The phenomenon, which appeared dynamic, progressive and transformational, emerged in the light of the interaction between the three sources of support revealed, which, as was graphed with the strands of the mother's braid, together nurtured and modulated the maternal experience of breastfeeding, which turned out to be the comprehensive category in which the influences of the different sources of support converged.

These sources of support began to be present in the prenatal period and as the process progressed, the interaction between them became increasingly close and necessary, since the varied support needs of mothers made visible the importance that the sources and types of support they provide evolved as the breastfeeding process progressed.

Each of the sources was shown to provide complementary support, so that the sources or types of support alternated in response to the mother's needs. These periods of alternating activation allowed the delivery of comprehensive support, which, when delivered constantly throughout the process, provoked in the mothers an enveloping perception of containment, which was considered fundamental for the breastfeeding experience to be gratifying and transforming, both for the mother and the child.

Figure 2: Representation of the phenomenon of the meaning of maternal experience on support during the breastfeeding process

From the above, it follows that the maternal experience of breastfeeding will be unveiled as the central comprehensive category. Thus, the participants stated that they considered it a unique and unrepeatable experience, as expressed by EM8 "I have lived like another experience with her (her daughter)" and as also mentioned by EM3 "it has been all new, a totally new experience", which also evolved as the breastfeeding process progressed, becoming an experience full of meanings related to love and closeness with her child, as was mentioned by EM10 ".... it is as if one loves one's child more... they are moments of intimacy between the child and oneself, it is nice, very nice... we look at each other, I sing to him and kiss his little hands...".

Through this experience, mothers enjoy a feeling of fullness, as EM3 commented "I believe that it is the best thing one can experience as a mother". As well as the feeling of self-confidence, as reported by EM1 "...I feel great, to be able to feed her myself... that it is I who can give her all the nutrients she needs, it makes me feel very good..." and EM3 "that I can feed her without having to give her any other type of milk, that she is being fed and that she is happy when she breastfeeds, for me it is wonderful".

As it has been mentioned, the breastfeeding experience is a process, a transition that culminates in very gratifying feelings. However, initially the participants mentioned having felt emotions that were far from these gratifying feelings, such as feeling pressured to breastfeed, as reported by EM7 "It was as if they were forcing you and you felt pressured". They also commented on the uncertainty and fear of not meeting their breastfeeding goals, as mentioned by MS2 "I didn't know if I would be able to...I was afraid that I wouldn't have enough milk or that my milk would stop before it was time".

There is frustration in the participants' accounts, as a result of the combination of the expectations they had and the feeling of being pressured by some people, including health professionals, as commented by EM7 "I thought it was going to be more relaxed, but it was like they put a knife to your neck and told you that you had to do it, like they were forcing you...". This sense of frustration led the mothers to feel insecure, as seen in the account of EM9 "when he cries and I put him to the breast and nothing, he cries and cries. So that's where I get frustrated and feel like I'm doing something wrong".

Initially, the participants also felt anguish, as mentioned by MS2 "Ahhh, I cried all the time, it was horrible, I sat down to cry". These feelings and perceptions made it difficult for the breastfeeding experience to be pleasant from the beginning, considering, in addition, that the mothers mentioned having felt physical pain caused by breastfeeding, which sometimes led them to think about stopping breastfeeding, as reported by EM4 "Well, at first the truth is that it was not very good because of the pain that one feels.... At those moments one hesitates to continue breastfeeding the baby and thinks about giving him a bottle and not breastfeeding him anymore, because the pain is really horrible, and it was not a situation that I was enjoying...".

According to the narratives, the fact that a mother establishes breastfeeding is related to a conscious decision to breastfeed, a determination based on the recognition of breast milk as the best food for her children and its great contribution to the creation of bonds full of meanings as mentioned by EM2 "...despite the pain we must continue because it is the best...they get sick less, J is a super healthy and super stimulated child...besides we have a different connection, the two of us".

The experiences narrated by the mothers revealed that breastfeeding is a complex process that evolves and transforms the experience progressively, as EM10 commented: "It has been less and less complicated in time... little by little the pain has gone away, the wounds have healed and of course, she is suckling better and better... It is not so complex anymore, now I just put the breast to her, and she looks for it by herself, drinks and we enjoy it...".

In this evolution, the mothers reported experiencing incomparable feelings of gratification and love, such as those initially reported; feelings that reach the point of triggering such happiness that the mothers feel nostalgic thinking that at some point they will stop living this experience, even though they recognize that it is a natural part of the process they are going through. This is how EM2 shared it: "She breastfeeds from me, we touch each other lovingly… we are both so happy because it is such a beautiful moment, so intimate... These are the things that one experiences when breastfeeding that make me nostalgic, it makes me feel sad to think that she will stop breastfeeding".

The participants mentioned that to have a successful experience as mentioned above, in addition to the desire to breastfeed, it is necessary to have the support of people they identify as meaningful, as EM4 commented: "I think it is due to the desire to breastfeed, the support I received when I came to the breastfeeding clinic and also the support from my husband. Even my eldest son was affectionate with me, he told me to relax, don't cry... it was like that also gave me more encouragement".

Consequently, the experience of support from health professionals emerged as a comprehensive category, and this source of support was acknowledged by the participants as a contribution to the transformation of the maternal breastfeeding experience.

Mothers with previous breastfeeding experience perceived that they received more support from health professionals compared to their own previous experience, as EM5 commented "... yes, now there is more support, before there was a lack of help for mothers... in the consultations there was a lack of integration of breastfeeding, but not now, now there is more than enough".

In the narratives, there was evidence of the existence of professional support focused on the care of emerging situations associated with technical difficulties in breastfeeding, so that the support in these cases was tangible, as reported by EM4 "...I came here to the clinic and they gave me an ointment to heal the wound and the truth is that it worked and that is why I continued breastfeeding".

The participants highlighted the support sessions where they were able to reinforce their knowledge about breastfeeding positions, milk extraction and conservation, as mentioned by EM1 "now they have helped me clarify a lot of things, the issue of pumping milk, that the breasts are not as full as before breastfeeding the baby, that milk can be stored, because I had no idea that milk could be stored".

Within this comprehensive category, emotional support emerges as a type of support provided by professionals, which was appreciated by the mothers, who reported feeling motivated, calm, and self-confident about the breastfeeding process, as mentioned by EM6 "...I was super motivated when I left the breastfeeding clinic, like very different, much calmer... I knew that it was not because I was a bad mother or because I was doing things wrong, but because it is a process...".

The mothers acknowledged the ability of the professionals to adapt the support to their needs and experiences and commented how it helped them not to feel prejudices or pressure to breastfeed, as mentioned by EM6 "the nurses here helped me to breastfeed well, they taught me about the issue of the supplementer to the finger. They didn't see the formula issue as terrible either. They also taught me well how to breastfeed, but if I could not, it was not so terrible that I should rely on formula... so I started to relax...".

On the other hand, the participants also reported having experienced professional support that did not respond to their needs or expectations, as some reported aggressive language and attention from professionals who did not respond to their demands, making them feel frustrated, insecure and even negligent, as reported by EM6 "...the truth is that the midwives and assistants are very rude in the neo (neonatology unit)... they are always scolding you, as if you were doing everything wrong. So, I would tell my partner, as I was crying, I want to get out of here...".

In the stories, the mothers mentioned that they felt little listened to and understood by some professionals, and commented on the need to adapt the language used by them and called for expressing greater empathy for their situation, as EM10 shared "...sometimes they impose a lot on you, ‘you have to breastfeed, no bottle’ and many times the baby cries and cries and you have to resort to the bottle... So many times they get angry, but they are not really in your shoes... and moreover they speak with words that you don't know".

The stories showed how the participants felt vulnerable in different ways, from rough verbal to physical treatment as seen in the previous stories; however, they argued that these actions were intended to benefit their children or as a learning experience for them, as commented by EM2 "... they were nasty; I have nothing to say about how they were with the babies, but with the moms they were rougher, but even so, I am grateful for how they were with me, I think that made me learn a little more...".

Regarding the above, the mothers mentioned the importance of starting professional support from pregnancy until the baby starts complementary feeding for it to be a meaningful professional support, as reported by EM1 "during pregnancy, it could be between the 6 or 7 months, because if you start it before, you may forget it... I think that until the baby starts to eat, at around the time the child is 6 months old". Other mothers recommended the support of professionals until the mother needs it, including the weaning process, as reported by MS2 "It is important, because it is not just saying ‘now, don't breastfeed anymore and that’s it’... it is something very important when you stop breastfeeding... It is something terrible, I think about stopping breastfeeding and it makes me feel very sad...".

The mothers said they wanted to learn and be part of the process in an active way to provide better care for their baby at home, as reported by EM2 "...there was a very unpleasant midwife, she would take my breast and pinch it without telling me anything and then she would send others to form my nipple, and I had to tell her, I need you to teach me how to do this well, I have not had other babies and I do not know about this topic".

Within their narratives, the participants also suggested different ways for professionals to provide support, such as simulation experiences, delivery of audiovisual material, telephone calls and creation of web pages, but they preferably mentioned group workshops as a good way to provide support, as EM6 commented "I imagine that the best way would be to gather the mothers... perhaps the same mothers who have already had children could tell their experiences and then feedback could be given by the professional".

The mothers acknowledged the need to provide continuity of care, as mentioned by EM2 "The bad thing is that in the clinics you are always see by different people and you have to tell everything all over again. There is no one person who is the definitive one and says to you, I am following J’s process from the beginning". They also reinforced the importance of health professionals being able to respond to their care needs in a timely manner, since they referred that in some cases they have to wait weeks to receive care, as MS1 commented "The support is there now, what I think should be improved is the waiting time for an available appointment... the idea is that when you have a problem, they don't tell you to come in three more months or two more months".

Regarding the health professionals who they identified as suitable to provide support, they mentioned midwives and nurses, as MS9 said "...the midwives because they are the ones with the experience and the ones who understand this, and the nurses because they are the main support for the baby here at the clinic". In this regard, MS8 also commented, "I think that it is the nurse, since the midwife is more dedicated to the pregnancy, but it is the nurse the one who helps us with the baby... I feel that in this aspect they are better qualified" and MS1 reinforced the idea by commenting "I think that the same person who would do the monthly checkups of the child and who would know about nutrition, about feeding the children".

It is worth mentioning that the mothers placed great value on the professional support being understanding, not imposing, and stressed the importance of the staff being respectful and empathetic, as recommended by EM10 "Listen to the mothers, the doubts they have, because suddenly there are places where you have a doubt and they get angry or sometimes want to impose... that they help the mothers, advise them, but above all that they understand them, because when you are a new mommy you are sensitive, sleepy, you are dealing with a lot of things...".

The results about the support around health professionals revealed the importance and the role that this support has in the breastfeeding process; so it is crucial, according to the narratives, to consider that depending on how this support is presented, it will act as a facilitator or an interfering factor in obtaining a rewarding breastfeeding experience.

When it comes to obtaining a gratifying breastfeeding experience, the participants mentioned how valuable it would be to include other people in the instances of support, people who are close and important in their process and who accompany them constantly at home. Most of them expressed their interest in having their partners considered in these instances of support, as stated by EM2 "I think that husbands or partners, because my husband is very important, he supported me a lot...".

For this reason, the experience of partner support emerged as a comprehensive category and one to which the participants attached special meaning.

According to the reports, the partner, as in the previous category, provides different types of support. On the one hand, the participants perceived that their partners provided them with spaces for a calmer breastfeeding and gave them greater well-being by sharing the care of the baby in their daily tasks, as commented by EM10 "For example, when I have things to do and he comes home from work, he holds E in his arms and takes her for a walk and then he leaves me there so that I can do the things I need to do or rest for a while.... He also helped me at night, when things got a little out of hand or he watched over her so I could sleep for a while... The greatest support I have had comes from him".

The mothers commented that their partner also gave them emotional support, acknowledging him as understanding and supportive, as mentioned by EM2 "I cried all the time, it was horrible, I would sit down to cry, my husband would arrive and he would tell me ‘Calm down, calm down because this is a new process for you’, and I was much calmer".

From the stories it emerged that the father's sensitivity to the needs of both the mother and the baby reinforced the trust in them as a meaningful source of support, which favored their active participation in breastfeeding moments and thus opened the way to greater involvement of the partners in this process, as expressed by EM1 "With my first child he supported me in every way, he helped me to put him to the breast, to find a better position... He used to burp the baby and now again, he tells me how to put him to the breast or he arranges the cushion so that I am in a better position...".

The mothers related this greater participation of the partner in the breastfeeding process to experiences that their partners lived with their own parents, which led them to carry out a conscious process around their expectations regarding the upbringing of their children, which involved the intention to connect with their child and the sensitivity that he was developing throughout the process, which in many cases responded to the intention of not repeating patterns that they experienced and identified as negative experiences, as shared by EM1 "Well he said he wanted to be the opposite of his dad, because his dad left his side very early, so he did not want the same for his children.... ".

All the stories showed the valuable meaning that the participants gave to the support of the partner in this process, they highlighted their partners as their main source of support, but also recognized as necessary the interaction with other sources of support identified, as EM10 comments: "My partner is the one who has been by my side the most... Well, and my daughter, she also helps me a lot to take care of her".

In relation to the above, the experience of support from other relatives emerged as a comprehensive category, which refers to relatives other than the partner, because even though the partner is also considered a relative, its importance made it emerge as a comprehensive category on its own.

In this category, the mothers reported that when family members had had personal experience with breastfeeding, the support they provided was based on the transmission of their own experience, which allowed them to accompany the mothers in their process, as reported by EM1 "before I started breastfeeding, my mother would tell me how her experience was and my grandmother would do the same, or she would tell me what I had to do, since she had had good breastfeeding...".

The mothers acknowledged that the support provided by their relatives facilitated the resolution of breastfeeding problems, as expressed by EM2 "My mother-in-law helped me a lot, she knew a gynecologist who gave her the name of the medicine for the nipples and with that I was doing quite well... She also helped me with warm cloths to let my milk flow, to calm the pain and to reduce the fever I had".

According to what was reported by the mothers, there are people who, without experiencing the breastfeeding process, provide support that is highly valued by the participants, as in the case of older children, where the support they provide includes carrying out daily life activities, as stated by EM10 "My daughter, she is also the one who helps me during the day, she helps me to take care of her when I have to do something, my room or do anything. She holds her for me for a little while and now that she is on a school break, she helps me a lot".

The mothers also mentioned that the support provided by their older children had a great emotional meaning for them, as EM4 commented: "When I was breastfeeding and I was crying, my older son would come up to me, hug me and tell me ‘Mom, it's going to get better’. It was like he felt the pain I was feeling and that was very moving".

In the narratives, the interaction that took place between the three sources of support was reflected in a transversal manner, which contributed to the transformation of the breastfeeding experience, through the delivery of comprehensive support, as it emerged in the narrative of EM6 ".... N is super supportive, I feel that I can rest on him, besides he accompanies me to the checkups and to the breastfeeding clinic, then he also learns... then he tells me "remember what the nurse told us", so he helps me a lot... and on the other hand there is my mother-in-law, who is not the typical mother-in-law, but someone who takes care for me and supports me a lot... she has been super generous in sharing with both of us everything she knows”. Table 2.

Discussion

This research unveiled how the maternal experience of breastfeeding is lived, which in the presence of promoting factors such as accompaniment, transits until becoming a gratifying experience, full of meanings related to love and ends up becoming a transforming experience for the woman who lives it, which coincides with what has been described by other authors. 10

The maternal breastfeeding experience was revealed as unique and unrepeatable even for the same person. Starting another breastfeeding experience means a new beginning, with new challenges and expectations, which is also described by other research, which adds that previous good experiences are a protective factor for the success of a new process, but it is not possible to ensure it. (16

Consistent with other research, this study revealed that mothers experience positive feelings and sensations in the favorable evolution of the breastfeeding process, such as the feeling of fullness and perception of self-efficacy. 17 This becomes important when considering that the greater the perception of self-efficacy, the greater the security with which the mother lives her breastfeeding process, also reducing the perceived barriers to maintain this health-promoting behavior, as postulated by Nola Pender's model of health promotion. 18

In agreement with other authors, this research reveals that the breastfeeding experience is a complex and dynamic process, which culminates in rewarding feelings. However, initially, feelings such as anguish, frustration, fear, insecurity, and uncertainty are present. In addition, mothers experience painful sensations, which make it more difficult to initiate the process. 19,20

The above can be considered as perceived barriers to action, which, as this research showed, can reduce the mothers’ self-confidence with their breastfeeding process and lead to early abandonment of breastfeeding, which is why other papers emphasize that the first month is a critical period in this process. 21

The conscious decision of mothers to breastfeed their children, even when they perceive barriers such as pain, is based on the mothers' recognition of breastfeeding as the best food for their children, both for its health and emotional benefits and, as other authors point out, for the recognition of its benefits to healthy child development. 10,22

Feelings such as love, satisfaction, happiness, and other emotions generated in the mothers as a result of a successful breastfeeding process create a kind of mutual dependence, which even leads mothers to feel nostalgia for moments that have not yet been lost, making visible the need for support for a respectful weaning. There are several investigations related to weaning; however, no research was found focused on the meanings or emotions that occur in mothers in relation to weaning when breastfeeding has been successful. (12,20,21

It was revealed in this research that the success of breastfeeding is also a result of the existence of people who accompany and provide sympathetic support to breastfeeding mothers, these people identified as meaningful were health professionals, family members and mainly the partner, a result that coincides with another research. 12,20,21,23,24

Regarding the support of health professionals, this research, in agreement with others, reveals that mothers perceive an increase in the instances of professional support related to breastfeeding. In them, support from a technical point of view is recognized, referring to assessment, assistance and educational instances regarding problems related to this process and its implications. 21,25,26

In relation to the above, the management of emergent situations was recognized as the central axis of the instances of accompaniment of health professionals, highlighting their ability to resolve difficulties that arose in the breastfeeding process, as other research has pointed out. 12,21,27

As stated in other studies, this research recognized the ability of health professionals to provide emotional support, highlighting that if it is sympathetic, it can be motivating, reassuring and contributes to the mothers' confidence in the breastfeeding process. (10,12

The sensitivity of the health professionals to the care needs of the mothers was valued, highlighting their ability to adapt the accompaniment instances so that they would be meaningful for those who participated in them, which coincides with what has been stated by other authors. 23

Mothers frequently expressed the feeling of pressure to breastfeed, sometimes exerted by what is socially expected as part of motherhood, but mainly the pressure exerted by health professionals was acknowledged. In this regard, other studies are more categorical and identify health professionals as the main triggers of this feeling, recognized as an important barrier to the success of the breastfeeding process. 21,28

In relation to the support that did not respond to care needs and, on the contrary, had a negative influence on obtaining a good initial experience, both this and other studies described the existence of mothers who experienced verbal, emotional and even physical abuse from care agents, distancing the practice of these professionals from approaches to care such as the humanized care described by Jean Watson. However, it is striking how these practices were normalized by mothers and recognized as learning instances. (11,29,30

In addition to the latter, there was also the mothers' perception that they sometimes felt that they were only spectators of the support provided by the professionals and, as mentioned by other authors, this lack of active participation caused frustration and demotivation in the mothers. 11,27,31) According to what was visualized in this research, it is possible to relate the above mentioned to the characteristics and context of both the caregiver and the recipient, which is supported even by authors in the field of pedagogy such as Paulo Freire. 32

Regarding the context of the mothers in the breastfeeding process, this research, like others, revealed that the support provided by the partners was fundamental to the success of the process and had a special meaning. On the one hand, this source of support participated as a collaborator in daily activities, which contributed to the creation of environments that provided greater tranquility and well-being to the mothers, highlighting, as in other studies, greater participation of the couples with their children in recreational activities. 11,33-35).

In addition, the emotional support provided by the partner was identified, which was valued and acknowledged by the mothers as essential to achieve a feeling of fullness during the process, highlighting that the father's sensitivity to the needs of the child and the mother makes him an understanding and supportive person. This agrees with what has been described by other authors, who add that the level of involvement of the partner and the areas in which they are involved can condition the success and duration of the breastfeeding process. 11,36,37

This and other research support the existence of more active fathers, both in the care of their children and in their role as partners. For this reason, it is important to mention the existence of factors that condition this support, revealing that both good experiences and perceived shortcomings as a child, influence expectations and the exercise of fatherhood.33,38

Just as the support of health professionals and the support of the partner were identified as fundamental parts of the breastfeeding experience, the support provided by other family members was also identified as one of the pillars of this central category. Consistent with what has been presented in other studies, this support varied depending on who provided it, as well as its context, since when the mothers received support from a family member who lived the breastfeeding experience, this translated into the transference of the experience, anticipating the mother, and reducing her anxiety. 17,24,39

In relation to the above, part of this transfer turns out to be a facilitating experience in the resolution of difficulties associated with breastfeeding such as pain, cracked nipples or even support in the identification of more complex pathological processes such as mastitis or depression. (40-43

On the other hand, within the support network, the existence of family members who have not had the experience of breastfeeding was highlighted, who provided valuable and recognized support. This type of support was provided by the older children and ranged from collaboration in daily activities to emotional support, which was revealed as understanding, compassionate and empathetic, managing to motivate and contain the mothers, thus contributing to the establishment and maintenance of breastfeeding of their siblings. Although in this research the older children were included in the comprehensive category of support from other relatives, no studies were found that alluded to the emotional support provided specifically by them or to their characteristics, such as those mentioned in this study and through which the purity of filial love is represented.

Conclusions

Unveiling the meaning of the maternal experience around the support of health professionals in the breastfeeding process brought to light that the three sources of support identified nurture and modulate the breastfeeding experience in a complementary manner, so that the indivisibility of the influences exerted by them is a constitutive characteristic for the support to be perceived by the mothers as supportive and nurturing.

For this reason, making interventions that include meaningful others will strengthen the support network and the accompaniment of mothers, contributing to the success of the breastfeeding process and therefore to the positive perception of this experience by both the mother and her child.

This research reaffirms the importance of sensitizing health professionals to the care needs of people undergoing the breastfeeding process, including the need to receive empathetic, compassionate, respectful, contextualized, and non-imposing care.

Consequently, to respond successfully and contribute to the perception and satisfaction of the mothers regarding the care received in the breastfeeding process, it is imperative to visualize breastfeeding from the perspective of rights and provide care centered on the person. In this way, dignity and humanity will be preserved as a characteristic that should be at the core of the care provided and through which the bonding that will reduce and channel the emotional burden of women who are breastfeeding will be allowed.

The above-mentioned highlights the need for continuing education of professionals, the strengthening of skills such as effective communication, as well as the recognition of the importance of feelings such as compassion and empathy.

This research reinforced the value that mothers place on the accompaniment to begin in the prenatal stage and continue until weaning, highlighting the multiprofessional work by recognizing nursing and midwifery professionals as apt to accompany this process, emphasizing the support of midwives in the prenatal stage, as well as the role of nursing professionals once the breastfeeding process begins.

In relation to weaning, and as a recommendation for future research, it was revealed the need to deepen the knowledge regarding the emotions and meanings that are present in this stage of the process and thus provide truly comprehensive care for mothers going through this difficult stage.

This study also revealed the need for future research to deepen knowledge about the meanings of the support provided by older children, which will make it possible to identify and direct care with greater congruence, enhancing their valuable contribution to the process experienced by their mothers.

Since this research was conducted with anonymous secondary data, it was not possible to return the description of the constructed phenomenon to the participants, nor to go deeper into those aspects that emerged from the analysis, these being the main limitations of this study. However, it contributes to the generation of comprehensive knowledge regarding the maternal experience of support in the breastfeeding process, providing background and foundations that seek to improve the conditions for mothers to experience successful, gratifying, and pleasurable breastfeeding, which promotes and protects breastfeeding, thus contributing to a healthier, sustainable, and more equitable world by offering all children a good starting point. Likewise, the knowledge generated contributes to the strengthening of nursing knowledge as a discipline.

REFERENCES

1. Glejzer C, Ciccarelli A, Chomnalez M, Ricci AG. La incidencia de las emociones sobre los procesos de aprendizaje en niños, niñas y jóvenes en contextos de vulnerabilidad social. Voces la Educ. (Internet) 2019 (consultado 11 de marzo de 2020);113-28. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340088556_La_incidencia_de_las_emociones_sobre_los_procesos_de_aprendizaje_en_ninos_ninas_y_jovenes_en_contextos_de_vulnerabilidad_social [ Links ]

2. Mikkonen J, Raphael D. Social determinants of health: The Canadian facts. (Internet) Toronto. York University School of Health Policy and Management; 2010 (consultado 11 de marzo de 2020). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.thecanadianfacts.org/The_Canadian_Facts.pdf [ Links ]

3. Raineri F, Gregorian M, Barbieri M, Zamorano M, Gorodisch R, Ortiz Z. Determinantes sociales y ambientales para el desarrollo de los niños y niñas desde el período del embarazo hasta los 5 años: bases para un diálogo deliberativo (Internet). Buenos Aires. UNICEF; 2015 (consultado 4 de marzo de 2020);1-90. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://fundacionkaleidos.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Determinantes-sociales-y-ambientales-para-el-desarrollo-de-los-nin%CC%83os-y-nin%CC%83as-desde-el-periodo-del-embarazo-hasta-los-5-an%CC%83os-1.pdf [ Links ]

4. Ospina JM, Jiménez ÁM, Betancourt EV. Influencia de la lactancia materna en la formación del vínculo y en el desarrollo psicomotor. Colección Académica Ciencias Soc. (Internet) 2016 (consultado 11 de marzo de 2020);3(2):1-10. Disponible en: file:///C:/Users/Usuario/Downloads/4481-Texto%20del%20art%C3%ADculo-8199-1-10-20200930.pdf [ Links ]

5. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Nutrición de la madre, el lactante y el niño pequeño (Internet). Organización Mundial de la Salud; 2018 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276443/A71_22-s p.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&ua=1. [ Links ]

6.Sanabria CP, Ravetllat Ballesté I. El enfoque de los derechos de la niñez y la adolescencia en las políticas públicas de salud. Pediatría (Asunción) (Internet) 2017 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);44(1):11-4. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.revistaspp.org/index.php/pediatria/article/view/147/142 [ Links ]

7. Caro P, Guerra X. Tendencia de la lactancia materna exclusiva en Chile antes y después de la implementación de la Ley postnatal parental. Rev Chil pediatría. (Internet) 2018 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);89(2):190-5. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0370-41062018000200190 [ Links ]

8. González-Burboa A, Miranda-Valdebenito N, Vera-Calzaretta A, Arteaga-Herrera O. Implementación de la política pública para el cuidado de la primera infancia en el contexto chileno: Una mirada desde salud al “Chile Crece Contigo”. Rev Salud Publica. (Internet) 2017 (consultado 4 de marzo de 2020);19(5):711-5. Disponible en: chrome-extension://dagcmkpagjlhakfdhnbomgmjdpkdklff/enhanced-reader.html?pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fbrxt.mendeley.com%2Fdocument%2Fcontent%2Faf908562-1e4d-3cd1-b026-7bf8c586ca26 [ Links ]

9. Rosso F, Skarmeta N, Sade A. Informe técnico: Encuesta nacional de la lactancia materna en la atención primaria ENALMA Chile 2013. MINSAL (Internet) 2013 (consultado 11 de marzo de 2020);47. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://web.minsal.cl/sites/default/files/INFORME_FINAL_ENALMA_2013.pdf [ Links ]

10. Lucchini-Raies C, Márquez-Doren F, Rivera-Martínez MS. I want to breastfeed my baby: Unvealing the experiences of women who lived difficulties in their breastfeeding process. Rev Chil Pediatr. (Internet) 2017 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);88(5):622-628. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0370-41062017000500008&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en [ Links ]

11. Mcfadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, Buchanan P, Taylor JL, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (Internet) 2017 (consultado 11 de marzo de 2020);2017(2). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub5/full [ Links ]

12. Becerra-Bulla F, Rocha-Calderón L, Fonseca-Silva DM, Bermúdez-Gordillo LA. The family and social environment of the mother as a factor that promotes or hinders breastfeeding. Rev Fac Med (Internet) 2015 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);63(2):217-27. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rfmun/v63n2/v63n2a06.pdf/#:~:text=El%20%E2%80%9Centorno%20social%20y%20familiar,como%20adecuada%20para%20su%20hijo . [ Links ]

13. Burns N, Grove S. Desarrollo de la práctica enfermera basada en la evidencia. Investigación en Enfermería. Elsevier; 2016. [ Links ]

14. Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing - Advancing the humanistic imperative. Health SA Gesondheid. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [ Links ]

15. Lolas Stepke F, Quezada S. Á. Pautas Éticas de Investigación en Sujetos Humanos: Nuevas Perspectivas. Santiago Chile Programa Reg Bioética OPS/OMS (Internet) 2003 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);1-151. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/chi/dmdocuments/pautas2.pdf [ Links ]

16. Huang Y, Ouyang YQ, Redding SR. Previous breastfeeding experience and its influence on breastfeeding outcomes in subsequent births: A systematic review. Women and Birth. Elsevier B.V. (Internet) 2019 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);32:303-9. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871519218303123?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

17. Ryan K, Team V, Alexander J. The theory of agency and breastfeeding. Psychol Heal. (Internet) 2017 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);32(3):312-29. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08870446.2016.1262369?scroll=top&needAccess=true [ Links ]

18. Hoyos A, Gladis Patricia, Blanco Borjas DM, Sánchez Ramos A, Ostiguín Meléndez RM. The model of health promotion proposed by Nola Pender. A reflection on your understanding. Enfermería Univ (Internet) 2011 (consultado 11 de marzo de 2020);8(4):16-23. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-70632011000400003&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es [ Links ]

19. Powell R, Davis M, Anderson AK. A qualitative look into mother’s breastfeeding experiences. J Neonatal Nurs. (Internet) 2014 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);20(6):259-65. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1355184114000386 [ Links ]

20. Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet (Internet) 2016 (consultado 4 de marzo de 2020);387(10017):491-504. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [ Links ]

21. Burns E, Schmied V. “The right help at the right time”: Positive constructions of peer and professional support for breastfeeding. Women and Birth (Internet) 2017 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);30(5):389-97. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871519216302116?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

22. López de Aberasturi Ibáñez de Garayo A, Santos Ibáñez N, Ramos Castro Y, García Franco M, Artola Gutiérrez C, Arara Vidal I. Prevalencia y determinantes de la lactancia materna: estudio Zorrotzaurre. Nutr hosp. (Internet) 2021(consultado 24 de mayo de 2021);38(1):50-59. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S0212-16112021000100050&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt [ Links ]

23.Hunter LJ, Da Motta G, McCourt C, Wiseman O, Rayment JL, Haora P, et al. Better together: A qualitative exploration of women’s perceptions and experiences of group antenatal care. Women and Birth (Internet) 2019 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);32(4):336-45. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871519218301197?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

24. Peres JF, Carvalho ARS, Viera CS, Linares AM, Christoffel MM, Toso BRG de O. Pregnant relationship quality with the closest people and breastfeeding. Esc Anna Nery. (Internet) 2021 (consultado 24 de mayo de 2021);25(2):1-7. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.scielo.br/j/ean/a/yb4nHhHCnXvNgjnPFzSqzzg/?lang=en&format=pdf [ Links ]

25. Hall H, McLelland G, Gilmour C, Cant R. “It’s those first few weeks”: Women’s views about breastfeeding support in an Australian outer metropolitan region. Women and Birth. (Internet) 2014 (consultado 4 de marzo de 2020);27(4):259-65. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871519214000602?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

26. Moraes BA, Strada JKR, Gasparin VA, Espirito-Santo LC do, Gouveia HG, Gonçalves A de C. Lactancia materna en los primeros seis meses de vida de los bebés atendidos por Consultoría de Lactancia. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. (Internet) 2021 (consultado 24 de mayo de 2021);29. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.scielo.br/j/rlae/a/5CS4DJJb7J8j3mPSQHMMFWR/?format=pdf&lang=es [ Links ]

27. Sutter C, Fiese BH, Lundquist A, Davis EC, McBride BA, Donovan SM. Sources of information and support for breastfeeding: Alignment with centers for disease control and prevention strategies. Breastfeed Med. (Internet) 2018 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);13(9):598-606. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6247975/ [ Links ]

28. de Almeida JM, de Araújo Barros Luz S, da Veiga Ued F. Support of breastfeeding by health professionals: integrative review of the literature. Rev Paul Pediatr English Ed (Internet). 2015 (consultado 5 de marzo de 2020);33(3):355-62. DOI: 10.1016/j.rppede.2015.06.016 [ Links ]

29. Watson J. Caring science and human caring theory: Transforming personal and professional practices of nursing and health care. J Health Hum Serv Adm. (Internet) 2009 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);31(4):466-82. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790743?seq=1 [ Links ]

30. Menon P, Nguyen PH, Saha KK, Khaled A, Kennedy A, Tran LM, et al. Impacts on Breastfeeding Practices of At-Scale Strategies That Combine Intensive Interpersonal Counseling, Mass Media, and Community Mobilization: Results of Cluster-Randomized Program Evaluations in Bangladesh and Viet Nam . PLoS Med. (Internet) 2016 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);13(10):e1002159. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5079648 / [ Links ]

31. Nursan C, Dilek K, Sevin A. A autoeficácia das mães quanto à lactância e os fatores que a afetam . Aquichan (Internet) 2014 (consultado 5 de marzo de 2020);14(3):327-35. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/aqui/v14n3/v14n3a05.pdf [ Links ]

32. Prado CVC, Fabbro MRC, Ferreira GI. Desmame precoce na perspectiva de puérperas: Uma abordagem dialógica. Texto e Context Enferm (Internet). 2016 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);25(2). DOI: 10.1590/0104-07072016001580015 [ Links ]

33. Aguayo F, Barker G, Kimelman E. Editorial: Paternidad y cuidado en América Latina-ausencias, presencias y transformaciones . Masculinities Soc Chang. (Internet) 2016 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);5(2):98-106. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304335775_Paternidad_y_Cuidado_en_America_Latina_Ausencias_Presencias_y_Transformaciones_Editorial [ Links ]

34. James L, Sweet L, Donnellan-Fernandez R. Breastfeeding initiation and support: A literature review of what women value and the impact of early discharge . Women and Birth. (Internet) 2017 (consultado 4 de marzo de 2020);30(2):87-99. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871519216301391?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

35. Márquez F, Lucchini C, Bertolozzi MR, Bustamante C, Strain H, Alcayaga C, et al. Experiencias y significados de ser padre por primera vez: una revisión sistemática cualitativa. Rev Chil Pediatría (Internet) 2019 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);90(1):78-87. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0370-41062019000100078 [ Links ]

36. Ogbo FA, Akombi BJ, Ahmed KY, Rwabilimbo AG, Ogbo AO, Uwaibi NE, et al. Breastfeeding in the community-how can partners/fathers help? A systematic review . Int J Environ Res Public Health (Internet) 2020 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);17(2):413. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7014137/ [ Links ]

37. Rempel LA, Rempel JK, Moore KCJ. Relationships between types of father breastfeeding support and breastfeeding outcomes. Matern Child Nutr (Internet) 2017 (consultado 2 de marzo de 2020);13(3):e12337. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/mcn.12337 [ Links ]

38. Brown A, Davies R. Fathers’ experiences of supporting breastfeeding: Challenges for breastfeeding promotion and education. Matern Child Nutr. (Internet) 2014 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);10(4):510-26. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4282396/ [ Links ]

39. Rodriguez Vazquez R, Losa-Iglesias ME, Corral-Liria I, Jiménez-Fernández R, Becerro-De-Bengoa-Vallejo R. Attitudes and Expectations in the Intergenerational Transmission of Breastfeeding: A Phenomenological Study. J Hum Lact. (Internet) 2017 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);33(3):588-94. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28582630/ [ Links ]

40. Wagner S, Kersuzan C, Gojard S, Tichit C, Nicklaus S, Thierry X, et al. Breastfeeding initiation and duration in France: The importance of intergenerational and previous maternal breastfeeding experiences - results from the nationwide ELFE study. Midwifery (Internet) 2018 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);69:67-75. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0266613818303176?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

41. Rodríguez Vázquez R. Papel de la abuela sobre la vivencia de la madre lactante. estudio fenomenológico. Teseo. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. (Internet) 2016 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/imprimirFicheroTesis.do?idFichero=3vs1kkp%2FrWw%3D [ Links ]

42. Angelo BH de B, Pontes CM, Sette GCS, Leal LP. Conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas de las abuelas en torno a la lactancia materna: una metasíntesis. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. (Internet) 2020 (consultado 10 de marzo de 2020);28. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v28/es_0104-1169-rlae-28-e3214.pdf [ Links ]

43. Pinzón G, Alzate M, Olaya G. Consejería en lactancia como apoyo para el inicio y mantenimiento de la lactancia materna exclusiva hasta los seis meses . Dr Interfacultades en Salud Pública. (Internet) 2015 (consultado 5 de marzo de 2020);1-8. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rfmun/v64n2/v64n2a14.pdf [ Links ]

How to cite: Carrasco Salazar, P., Márquez-Doren, F., y Lucchini-Raies, C. Meaning of the Maternal Experience of Support during the Breastfeeding Process. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2021; 10(2): 03-28. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v10i2.2422

Contribution of the authors: a) Study conception and design, b) Data acquisition, c) Data analysis and interpretation, d) Writing of the manuscript, e) Critical review of the manuscript. P. C. S. contributed in a, c, d, e; F. M. D. in b, e and C. L. R. in b, e.

Received: July 06, 2020; Accepted: June 02, 2021

texto en

texto en