Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.10 no.1 Montevideo June 2021 Epub June 01, 2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v10i1.2412

Original Articles

Communication between the user critically ill adult and the nursing professional: an integrative review

3 Universidad Católica del Maule. Chile pceballos@ucm.cl

Keywords: health communication; nursing; critical care; patients.

Palabras clave: comunicación en salud; enfermería; cuidados críticos; pacientes.

Palavras-chave: comunicação em saúde; enfermagem; cuidados críticos; pacientes.

Introduction

The term communication comes from the Latin comunicare, which means to share. Communication is understood as the complex process that involves the exchange of information, data, ideas, opinions, experiences, attitudes and feelings between two or more people, playing an important role in the development of any human interaction. (1) For nurses, interaction is essential, and one of its essential tools is communication. (2) To achieve interaction, several types of communication are known; the most used is verbal communication, since it allows immediate feedback. However, it is also important that the communication not only consists of words or tone of voice, but also body language, known as nonverbal communication, which corresponds to approximately 70 % of the language used; and it is there where the observation capacity of the nursing professional acquires a prominent role. It is made explicit that health care in critical units does not only consist of observing signs and symptoms caused by a given health alteration, but is also based on recognizing the response to the different actions performed by the health team, (3-4) by means of both verbal and nonverbal communication.

Thus, nurses working in such units face very difficult situations in their health care work, such as the delivery of care in patients whose life is at risk, contact with patients who died, and suffering of family members and loved ones of the patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), among others. (5)

This highlights the importance of communication which improves the effectiveness and safety of health care, in which nursing professionals should communicate adequately, in order to assertively and safely work during their workday. (6) The nursing professional provides continuous care to patients and assists their needs of biological, technical, psychological, social and spiritual nature considering the needs of the patient and family. The complication that exists with critical patients is that, in most cases, they are with some degree of alteration of their state of consciousness, either pathophysiological or induced, so that their communication is limited, making the nurse-patient interaction difficult. (7)

For this reason, an integrative literature review was carried out with the purpose of analyzing how communication between critically ill adult patients and nursing professionals is carried out in the scientific literature that was reviewed.

Materials and Methods

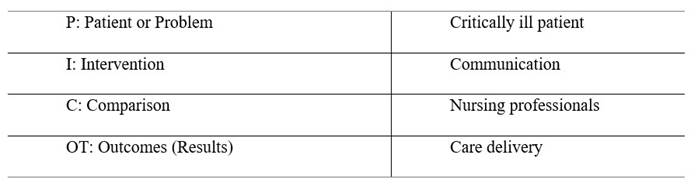

An integrative review was conducted, using the structure proposed by Souza (2010), which proposes six phases: a) research question, b) literature search, c) information gathering, d) critical assessments, e) discussion of results, and f) presentation of the integrative review (8). The guiding question of this review was: How do critically ill patients communicate with nursing professionals for the delivery of care? This question emerged using an adaptation of the PICOT structure (9), which is explained in the table. Table 1

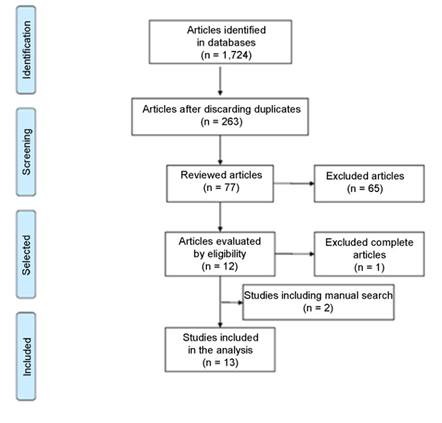

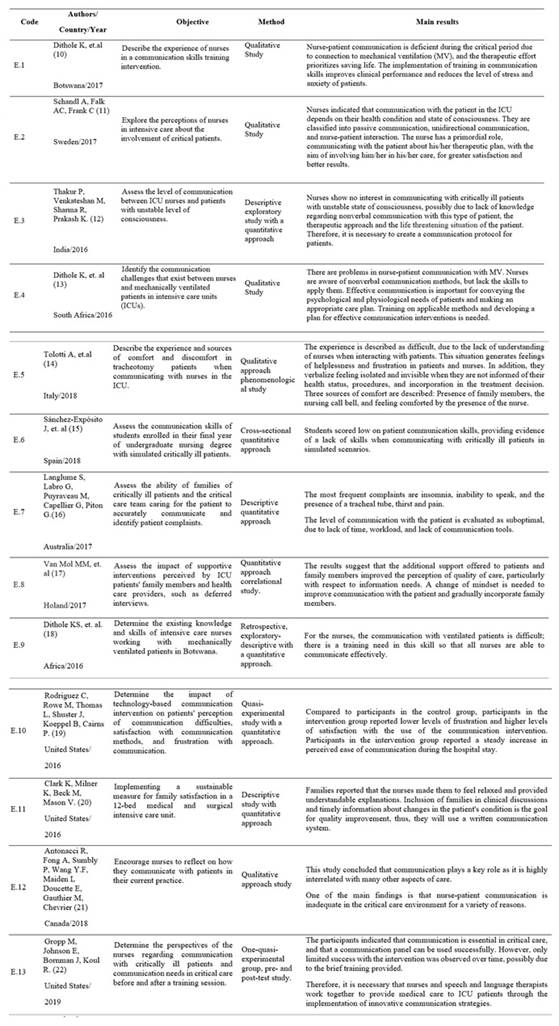

The literature search was performed in several databases such as CINAHL complete and PubMed, using health sciences descriptors (DeCs): nurse communication, patients, critical care, ICU and intensive care, combining them with the help of the Boolean operators AND and OR. A total of 1724 publications were found. Subsequently, the following criteria were used to choose the proper publications that were published in recent years (2016-2019), of full-text articles written in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. After evaluating duplication of articles, those that met inclusion criteria were selected, namely, critically ill adult patient on mechanical ventilation, communication with the adult patient with altered level of consciousness, communication skills of the nursing professional and students; however, studies in pediatric population, non-critical patient-nurse communication, communication with other health professionals, communication, nurse and health team were excluded. For data collection, an instrument prepared by the authors of the document was used, which was comprised by 6 variables, described in Table 2. With the purpose of answering the guiding question of the review, 11 articles were selected and 2 were added by manual search, as shown in Figure 1. It should be noted that for the development of the three categories of arguments, a critical assessment of the evidence found was performed, according to Souza (2010), which is described in Table 3 and discussed in the discussion section of the results.

Results

Of the total number of studies, 53.9 % correspond to the quantitative approach (10, 13, 14 - 17, 21) and a 46.1 % report using the qualitative approach (8-9, 11-12, 18, 22), which shows an homogeneous distribution in the research approach, reflecting levels, experiences, lived experiences, attitudes and needs of the patients and the nursing professionals from an integral point of view. Regarding the place where the studies were performed, 30.8 % were conducted in Europe (9, 12-13, 15), the same percentage of the studies were conducted in North America (11, 12, 21, 22). Latin America is the only continent that does not report studies on this subject. Regarding the communication between the critically ill patient and the nursing professional, the following assessment of the research previously described in Table 2 is obtained, so it is possible to classify the communication between the nurse and the critically ill patient.

Discussion

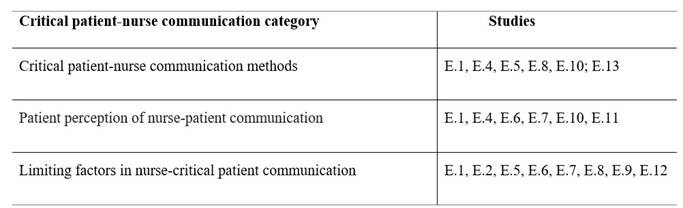

To facilitate the understanding of this section, we developed a table that makes visible the three argument categories (Table 3), which emerged from the critical assessment conducted by the authors of the document, according to Souza (2010).

Table 3: Classification of studies according to the category of critical patient-nurse communication

Source: own development.

Critically patient-nurse communication methods

As the first element of study in this category, we want to highlight the importance of communication between nursing professionals and the critically ill patient, who is unable to communicate verbally either because of his status of gravity, consciousness, sedation, endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation (10, 12-13, 23), or the use of physical restraint measures, for his safety and treatment. Thus, nonverbal communication is the communication methods most used by nursing professionals in these cases. Other articles report the importance of gaining the trust of the patient previous to the communication; then, as main nonverbal communication methods are indicated, namely, eye contact, gestures, sounds, interpretation of lip reading or touch, and verifying all patient responses (24-25), regarding the latter, studies show that some nurses are able to interpret vital signs, such as increased heart rate or blood pressure in response to verbal stimuli. (12 - 14)

Another important aspect that appears when analyzing the articles is how the need for communication changes when the patient is stabilized and comes out of life threatening status. At this moment, the ill person encounters barriers of communication, such as invasive devices, throat discomfort, fear, among others, and it is here when communication deficiencies become more critical. Most studies agree that there is a lack of tools, skills, and training opportunities for the personnel (8 - 10, 16, 22), which will make possible to identify the communication limitations and analyze the most efficient communication method for them in this stage of greater connection with the environment.

Studies not only focus on nonverbal communication, but some of them mention as communication tools or methods the use of chalkboards and alphabet charts (13, 22), nursing call bell and presence of family members. (14) However, these are pilot or individual evidences, and they are not standardized to be replicated in the different ICUs. Therefore, it is necessary to elaborate evidence-based practice guidelines, highlighting the importance of using tools for critical patient-nurse communication, which can be adapted to the local context, achieving greater adherence and acceptance with respect to the communication tools will be visible in clinical practice. (26)

It is indicated that by having nonverbal communication methods, nursing professionals develop more tools to be able to care for patients (19), establishing better communication and including the patient, empowering him/her in the decision making process and in the application of the therapeutic plan. (10)

Patient perception of nurse-patient communication

Patients in the ICU, due to their life threatening situation and pathology, often experience communication difficulties, which are generally associated with mechanical ventilation and the presence of the endotracheal tube, making them unable to speak (16), which is a major limitation when communicating, causing psychological problems such as anxiety, fear and depression. (10)

As for the patients' perception, they report feeling helpless and frustrated for not being able to use their voice; many stated having tried to shout to call the nursing professional, even though they knew they could not, which causes them feelings of frustration. The inability to speak was experienced as “not being able to do anything,” as if the absence of voice blocked other human actions of communication. This continuous frustration produces feelings of resignation, abandonment, invisibility (14), and anger in the patients. (15) Moreover, they express that the intention to make gestures, use eyes and head movements was often a complex consequence of reduced mobility, restraint and sedation. This inability to communicate, in turn, generates feelings of isolation in the patient. Among the potential factors of nurse-patient communication described here, the following are considered: The presence of a family member, the help of the family member who acts as an interpreter between the patient and the nursing professional, the presence of a hand-help bell and a nurse at the bedside. (15, 19-20)

Limiting factors in nurse-critical patient communication

The assessment of the articles found showed the lack of time generated by the workload, according to the nursing professionals (16, 21), associated to the limited participation of the patient in the ICU, due to his health condition, inability to speak, sedation, motor disability, among others (14, 16, 19), and the status of consciousness of the patient (10-11). In addition to this background, in all the contexts reviewed, the main concern for the nursing professional in these units is to maintain the patient's life, therefore, emphasizing clinical parameters and the manifestations of the patient, through hemodynamics, concentrating much of his time on actions resulting from the diagnosis and medical treatment (8), which postpone or minimize the communication with the patient.

Additionally, studies have sugested the need for regular training in communication skills for nurses in the ICU, establishing that patients who are seriously ill generally remember very clearly the communication with the nursing professional, even if they were unconscious most of the time. (11) The lack of communication and skills from the nurses to socialize with mechanically ventilated patients (10 - 12, 18) is often related to lack of knowledge. (15) In this regard, it is possible that nursing professionals have had little training in communication skills at undergraduate level, so it may be necessary to review the training curricula in Latin America, to develop these skills in future professionals, and, also, to prepare training programs to provide support to these professionals (13, 17-18), in addition to the implementation of workshops to improve these skills to apply the use of alternative communication devices and to promote nurse-patient communication and interaction. (10, 22)

Another limitation evidenced in the review is the inclusion of the family throughout the hospitalization process. Although this review is focused on communication between the nursing professional and the patient, the latter cannot be separated from his/her environment. (27) Just as the articles evidenced fear and anxiety, their family members or close acquaintances require contact with the patient's healthcare givers to inform about health care actions. Evidence indicates that the family is the best link for interpretation of the patient's needs, being an ally for a good nurse-critically ill patient communication. (14, 17)

Conclusions

This document allows us to conclude that at the Latin American level there is no published scientific evidence on the communication between nurse and critically ill adult patients, which opens a gap to be researched for this type of professionals. The barriers that exist in the Latin American population, population who has its own idiosyncrasy, are unknown; thus, it is necessary to make more research and publications on the subject.

Moreover, it is evident that nursing professionals in ICU focus almost entirely on actions resulting from the diagnosis and medical treatment, putting on a second plane the aspects of interrelation with the patient and his family. This highlights the importance of the need of training on communication skills to improve the nurse-patient relationship, strengthening the participation of the patient and family in making care decisions, allowing nursing professionals to be active agents of change within the ICU, therefore, enhancing a humanized health care.

Finally, nursing professionals should consider family members or the patient's environment in their health care scheduling, given their importance for the recovery and communication of the critically ill patient.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the Centro de Investigación del Cuidado UC del Maule for their collaboration in the structure and development of this document.

REFERENCES

1. Rivera AB, Rojas LR, Ramírez F, Álvarez de Fernández T. La comunicación como herramienta de gestión organizacional. Negotium. 2005; 1(2): 32-48. Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=78212103 [ Links ]

2. Kourkouta L, Papathanasiou I. Communication in Nursing Practice. Mater Sociomed. 2014; 26(1): 65-7. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2014.26.65-67 [ Links ]

3. Cibanal LJAS, Carballal MCB. Técnicas de comunicación y relación de ayuda en ciencias de la salud. 2° ed. España: Elsevier España; 2010. p. 35-50. [ Links ]

4. Bautista Rodríguez LM, Arias Velandia MF, Carreño Leiva ZO. Percepción de los familiares de pacientes críticos hospitalizados respecto a la comunicación y apoyo emocional. Rev. Cuid. 2016; 7(2): 1297-309. Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=359546229007 [ Links ]

5. Landete L. La comunicación pieza clave en enfermería. Enfermería Dermatológica. 2012; 16(1): 16-9. Disponible en: https://www.anedidic.com/descargas/formacion-dermatologica/16/La-comunicacion-pieza-clave-en-enfermeria.pdf [ Links ]

6. Moreira FTLS, Callou RCM, Albuquerque GA, Oliveira R. Effective communication strategies for managing disruptive behaviors and promoting patient safety. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2019; 40(spe): e20180308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2019.20180308 [ Links ]

7. Ayuso-Murillo D, Colomer-Sánchez A, Herrera-Peco I. Habilidades de comunicación en enfermeras de UCI y de hospitalización de adultos. Enfermería Intensiva. 2017; 28(3): 105-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2016.10.006 [ Links ]

8. Souza M, Silva M, Carvalho R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein. 2010; 2(1): 102-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134 [ Links ]

9. Peña Herrera C, Soria J. Pregunta de investigación y estrategia PICOT. Rev. Med. FCM-UCSG. 2015; 19(1): 66-9. https://doi.org/10.23878/medicina.v19i1.647 [ Links ]

10. Dithole K, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Oluwaseyi A, Moleki M. Communication skills intervention: promoting effective communication between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Nursing. 2017; 16: 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0268-5 [ Links ]

11. Schandl A, Falk AC, Frank C. Patient participation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017; 42: 105-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.006 [ Links ]

12. Thakur P, Venkateshan M, Sharma R, Prakash K. Nurses Communication with Altered Level of Consciousness Patients. International journal of nursing education. 2016; 8(3): 51-56. [ Links ]

13. Dithole K, Sibanda S, Moleki MM, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G. Exploring communication challenges between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients in the Intensive Care Unit: A structured review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016; 13(3): 197-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12146 [ Links ]

14. Tolotti A, Bagnasco A, Catania G, Aleo G, Pagnucci N, Cadorin L, Zanini M, Rocco G, Stievano A, Carnevale FA, Sasso L. The communication experience of tracheostomy patients with nurses in the intensive care unit: A phenomenological study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018; 46: 24-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2018.01.001 [ Links ]

15. Sánchez-Expósito J, Leal Costa C, Díaz Agea JL, Carrillo Izquierdo MD, Jiménez Rodríguez D. Ensuring relational competency in critical care: Importance of nursing students' communication skills. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018; 44:85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.08.010 [ Links ]

16. Langlume S, Labro G, Puyraveau M, Capellier G, Piton G. Estimation of critically ill patients’ complaints by the nurse, the physician and the patient’s family: A prospective comparative study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2017; 43: 55-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.07.002 [ Links ]

17. Van Mol MM, Boeter TG, Verharen L, Kompanje EJ, Bakker J1, Nijkamp MD. Patient- and family-centred care in the intensive care unit: a challenge in the daily practice of healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs. 2017; 26(19-20):3212-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13669 [ Links ]

18. Dithole KS, Sibanda S, Moleki MM, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G. Nurses' communication with patients who are mechanically ventilated in intensive care: the Botswana experience. Int Nurs Rev. 2016; 63(3): 415-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12262 [ Links ]

19. Rodriguez C, Rowe M, Thomas L, Shuster J, Koeppel B, Cairns P. Enhancing the Communication Process of Suddenly Speechless Patients in the Critical Care Setting. Am J Crit Care. 2016; 25(3): e40-e47. https://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2016217 [ Links ]

20. Clark K, Milner K, Beck M, Mason V. Measuring Family Satisfaction with Care Delivered in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2016; 36(6): e8-e14. https://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ccn2016276 [ Links ]

21. Antonacci R, Fong A, Sumbly P, Wang Y.F, Maiden L Doucette E, Gauthier M, Chevrier A. They can gear the silence: Nursing practices on communication with patients. Canadian Journal of Critical Care Nursing, 2018; 29(4): 36-9. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2011433 [ Links ]

22. Gropp M, Johnson E, Bornman J, Koul R. Nurse’s perspectives about communication with patients in an intensive care setting using a communication board: A pilot study. Health SA Gesundheit 2019; 24(0): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v24i0.1162 [ Links ]

23. Baker C, Melby V. An investigation into the attitudes and practices of intensive care nurses towards verbal communication with unconscious patients. J Clin Nurs. 1996; 5(3): 185-92. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.1996.tb00248.x [ Links ]

24. Nilsen ML, Happ MB, Donovan H, Barnato A, Hoffman L, Sereika SM. Adaptation of communication interaction behaviour instrument for use in mechanically ventilated, Nonvocal Older Adults. Nurs. 2014; 63: 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000012 [ Links ]

25. Radtke TV, Tate JA, Happ MB. Nurses perception of communication training in the ICU. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 2012; 28(1): 16-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2011.11.005 [ Links ]

26. Alegría L, Pedrero V, Fuentes I, Sanhueza MA, Toro M, Díaz P et al. Documento de Consenso Una aproximación a la práctica de enfermería basada en la evidencia en unidad de paciente crítico. Rev Chilena Medicina intensiva. 2016; 31(3): 149-61. Disponible en: https://www.medicina-intensiva.cl/reco/mbe_2016.pdf [ Links ]

27. Vílchez-Barboza V, Paravic-Klijn T, Salazar-Molina A. La escuela de pensamiento Humanbecoming: una alternativa para la práctica de la enfermería. Cienc Enferm. 2013; (2): 23-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95532013000200003 [ Links ]

How to cite: Espinoza-Caifil M, Baeza-Daza P, Rivera-Rojas F, Ceballos-Vázquez P. Communication between the user critically ill adult and the nursing professional: an integrative review. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2021; 10(1): 30-43. Doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v10i1.2412

Contribución de los autores: a) Concepción y diseño del trabajo, b) Adquisición de datos, c) Análisis e interpretación de datos, d) Redacción del manuscrito, e) Revisión crítica del manuscrito. M. E-C. has contributed in a, b, c, d; P. B-D. in a, b, c, d; F.R-R. in d, e; P. C-V. in a, c, d, e.

Received: July 02, 2020; Accepted: April 21, 2021

text in

text in