Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

Print version ISSN 1688-8375On-line version ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.9 no.2 Montevideo Dec. 2020 Epub Dec 01, 2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v9i2.2288

Original articles

Male partner participation in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: health team members´ perceptions in Bogota

1 Universidad El Bosque. Colombia

2 Subred Integrada de Salud Norte, Bogotá.Colombia

Introduction: Partner accompaniment on perinatal health obeys the principles of humanized childbirth. Objective: Describe the health team members perception on the male partner participation in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum. Method: Qualitative study based on three focus groups, a deliberative forum and six in depth interviews. Participated 49 members of the health team (medicine doctors, nurses, medical interns and nursing assistants). A thematic analysis was carried out with the support of Atlas ti 8 software. Results: There is a positive perception of the male partner participation in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum especially as an emotional support for the pregnant woman. As limitations, cultural barriers associated with traditional gender roles in which men are excluded from reproductive processes, some institutional access barriers related to infrastructure and protocols are relevant. Women often face pregnancy and childbirth alone; men fear and feel that being part of the process is not appropriate to their role; there is reluctance in some health professionals. The following alternatives are proposed: generating cultural and institutional changes to include men in reproductive health, adapting spaces and resources, strengthening awareness processes for health personnel and improving information and training for users. Conclusions: It is required openness to new masculinities in the reproductive field, eliminate access barriers and design innovative strategies for welcoming and educating men based on their particular needs.

Keywords: maternal health; pregnancy; humanized delivery; masculinity; health personnel; qualitative research

Introducción: El acompañamiento de la pareja a la gestante obedece a los principios del parto humanizado. Objetivo: Describir la percepción del equipo de salud sobre la participación de la pareja masculina en el embarazo, parto y postparto. Metodología: Estudio cualitativo basado en tres grupos focales, un conversatorio y seis entrevistas a profundidad. Participaron 49 miembros del equipo de salud (médicos, enfermeras, internos de medicina y auxiliares de enfermería). Se realizó un análisis temático con apoyo del software Atlas ti 8. Resultados: Hay una percepción positiva sobre la inclusión de la pareja en el proceso reproductivo, especialmente como apoyo emocional a la gestante. Como limitaciones se destacan barreras culturales asociadas al género en que los hombres son excluidos de los procesos reproductivos y barreras de acceso relacionadas con la infraestructura y ciertos protocolos institucionales. Las mujeres con frecuencia asumen a solas la gestación y parto; los hombres no se sienten apropiados de su papel y temen hacer parte del proceso; hay reticencia en algunos profesionales de salud. Como alternativas se propone: generar cambios culturales e institucionales que incluyan a los hombres en la salud reproductiva, adecuar espacios y recursos, fortalecer procesos de sensibilización al personal de salud y mejorar la información y preparación de los usuarios. Conclusiones: Se requiere una apertura a las nuevas masculinidades en los ámbitos reproductivos, eliminar barreras de acceso que persisten y diseñar estrategias innovadoras de acogida y educación a los hombres basadas en sus necesidades particulares.

Palabras claves: salud materna; embarazo; parto humanizado; masculinidad; personal de salud; investigación cualitativa

Introdução: O acompanhamento do casal à gestante obedece aos princípios do parto humanizado. Objetivo: Descrever a perspectiva dos profissionais de saúde sobre a participação do parceiro masculino na gravidez, parto e pós-parto. Método: Estudo qualitativo baseado em três grupos focais, um grupo de conversação e seis entrevistas em profundidade. Participaram 49 membros da equipe de saúde (médicos, enfermeiros, estagiários e auxiliares de enfermagem). A análise temática foi realizada com o apoio do software Atlas ti 8. Resultados: Existe uma percepção positiva da inclusão do parceiro no processo reprodutivo, especialmente como suporte emocional à gestante. Como limitações, destacam-se as barreiras culturais associadas ao gênero, nas quais os homens são excluídos dos processos reprodutivos e algunsas barreiras institucionais de acesso à infraestrutura e alguns protocolos. As mulheres geralmente assumem a gravidez e o parto sozinhos; os homens não se sentem adequados ao seu papel e temem fazer parte do processo; há relutância em alguns profissionais de saúde. As seguintes alternativas são propostas: gerar mudanças culturais e institucionais que incluam homens em saúde reprodutiva, fortalecer processos de conscientização do pessoal de saúde, adaptar espaços e recursos e melhorar as informações e o treinamento dos usuários. Conclusões: É necessária uma abertura a novas masculinidades nos campos reprodutivos, removendo barreiras institucionais de acesso e projectar estratégias inovadoras para acolher e educar homens com base em suas necessidades particulares.

Palavras-chave: saúde materna; gravidez; parto humanizado; masculinidade; pessoal de saúde; pesquisa qualitativa

Introduction

The importance of gender equality, responsible and committed male participation in sexuality and reproduction as well as the equal sharing of responsibilities between women and men in family care has been clearly stated at Cairo 1 and Beijing 2 international conferences. The National Policy on Sexuality, Sexual Rights and Reproductive Rights 3 has retaken this commitment in Colombia.

Evidence indicates that the partner active involvement in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum (PCP) reduces maternal risk and influences mother-child well-being 4. Permanent emotional support can reduce the pain of women during childbirth, encourages natural childbirth and makes more comfortable the whole experience 5. During pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum women desire to count on their partners’ involvement and support 6. In humanized childbirth, the father´s role acquires special prominence 7). Despite the fact that men are increasingly interested in becoming part of the pregnant women care, they encounter cultural and institutional barriers that create limitations and keep them away from reproductive processes 8. Aspects related to the health system hamper those who are willing to support their partners in childbirth 9. Health personnel play a crucial role in changing this situation 10. The transformation of hospital policies can facilitate male integration into maternal care by providing men tools to assume their role in this context 11.

There is relatively little research in male partner participation in maternal health from the point of view of health personnel members although their role is essential for strengthening the male involvement in PPE. Consequently, one of the integrated health subnetwork in Bogotá (made up of three hospitals of the public system), has sought to know, from the health team members perception, the strengths and critical points for the implementation of this strategy as a component of humanized childbirth in which the institution is committed to. The findings obtained from this study will contribute to build paths for strengthening male participation in PCP as a key element in the humanization of childbirth.

Objective

Describe the health team members perception about the male partner participation in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum.

Methodology

The study was conducted from a qualitative epistemology. A constructive-interpretative model that deals with exploring subjectivities 12 leads this type of research. A descriptive phenomenological approach was adopted which aims to describe the meaning of a certain experience from the subject’s point of view 13. For this study focus groups, in-depth interviews and deliberative forum techniques were implemented, including as participants members of the medical staff (physician and medical interns) and nursing staff (professionals and auxiliaries) from three hospitals that belong to a health services subnetwork in Bogota.

The focus group technique is especially sensitive for addressing attitudes and experiences; it facilitates exploring opinions developed and operating in certain cultural context 14. The individual semi-structured interview includes open questions through which participants can express their opinions and clarify their answers 15. This technique is an effective method for obtaining complete and deep information and can be complemented with other techniques depending on the specific nature of the research 16. Discussion or deliberative forum is a participatory research technique. Participatory research involves people sharing same problems in its analysis and searching for solutions 17. The group conversation obeys to a logic of intersubjective connection. The conversation "makes common sense in an alternative way compared to the usual ways in which everyday life is reproduced." In conversations, a relationship with language becomes possible and the autonomy of the subject is developed at the same time that group sense is reinforced. In conversation, “you can talk, but you can also talk about what you hear” 18.

An emergent purposive sampling (or opportunity sampling), as described by Martinez, was considered: the paths emerging during the fieldwork are followed permitting flexibility and allowing taking advantage of the unexpected. In accordance with the author, the number of participants depends on the study purpose and on what is needed to achieve: "what is at stake, what makes it plausible, and ultimately, what is possible” 19. Forty-Nine members of the health team from the three hospitals that make up the subnetwork participated. At first, two focus group sessions with a total of nine nurses, two focus groups sessions in which nine nursing assistants participated and one focus group with four medical interns were carried out; in addition, two in-depth interviews with medical interns and four in-depth interviews with physicians (three obstetrician gynecologists and one general practitioner) were conducted. In a second moment, a group conversation was held with 21 nurses from the three hospitals.

The most important inclusion criteria were that participants had a minimum of six months collaborating in the maternal perinatal area in one of the three hospitals of the subnetwork. The exclusion criteria were as follows: team members who were not interest in participating in the study, who could not attend the call due to lack time, who belonged to other subnetwork and who were not working in the maternal perinatal area at the time of data collection. Participants were previously invited to participate and those who agreed signed an informed consent.

Information was collected in places specially enabled for this in the different hospitals and data collection process was carried out by the main researcher who had no prior relationship with the participants or with the institution, which guaranteed the confidentiality of the process.

The following topics were discussed with the participants, considering the health subnetwork context: 1) Which are their expectations regarding male partner participation in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum, 2) What aspects facilitate male partner participation in PCP, 3) Which are the barriers that limit the participation of the male partner in PCP and 4) Which proposals arise to strengthen the male partner participation in PCP.

The diversity of the strategies used in this study is related to the feasibility of obtaining an approach to the different members of the health team in the fieldwork. In the case of physicians, conducting focus groups was hampered by the permanent commitment of these professionals to care in the delivery room, which limited the possibility of bringing together several of them at the same time. That is why it was decided to conduct in-depth interviews with them. After the first stage of the study, the importance of deepening the institutional barriers to the participation of the male partner in PPE and developing strategies to reduce them was seen. Given the special involvement of nurses in the humanized delivery processes and in the respective care routes, in a second moment they were invited to participate in a deliberative forum, taking advantage of the fact that a good number of them would be gathered at an academic event. Twenty-one nurses from the three hospitals in the subnetwork agreed to participate in the study.

The interviews, focus groups and forum discussion were recorded with the participants’ authorization and were transcribed. A thematic analysis of the data was carried out. In this analysis, thematic units are defined as the product of a selective approach, based on the reading and rereading of the information. This process, described by Mieles et al. 20, starting from the sequence proposed by Braun and Clarke to strengthen scientific rigor in studies of this nature, involves the following stages: 1) Familiarization with the data, 2) Generation of initial codes, 3) Search for topics, 4) Review topics, 5) Definition and naming of topics and 6) Final document production.

Through an inductive process, with the support of the Atlas ti 8® software, the coding and definition of emerging issues was oriented, starting from the five general categories that were described a priori in the objectives and that guided the questions presented above. Those are: a) Health team members’ expectations about the male partner participation in PCP, b) Aspects that facilitate this participation c) Barriers that limit the male partner participation in PCP and d) Proposals for changing situation.

In scientific rigor or credibility field, validity refers to the degree of fidelity with which the results show the phenomenon under investigation. It can be achieved through methods such as triangulation, saturation, and contrast with data obtained by other researchers 21. In this study, validity criteria by triangulation were implemented through the use of three different inquiry techniques and the agreement between the two researchers, and by contrast, by comparing the study findings with the scientific literature. This work was approved, according to ethical and technical evaluation, by the Research and Social Projection Committee of the Faculty of Nursing of El Bosque University in session number 0143 of September 13, 2018. As proposed by the Declaration of Helsinki 2013 22, it was taken into account the importance of safeguarding dignity, integrity and rights of human beings, as well as confidentiality. The informed consent implemented was of the written type and allowed the participants to understand the objectives and other details of the study and the conditions of their participation. Names or hospital institutions are not included in order to preserve the anonymity of the participants.

Results

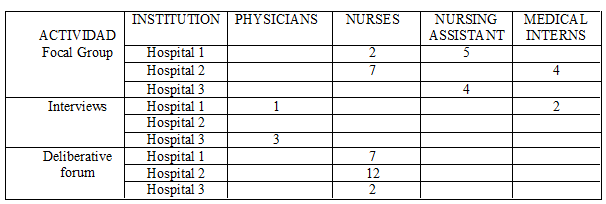

The integrated health subnetwork, where the study was carried out, is made up of three public hospitals with highly complex obstetric services. Table 1 shows the distribution of the participants according to the activity in which they participated and the hospital to which they are linked.

From Hospital 1, 15 members of the health team participated; from Hospital 2, 23 participated, and from Hospital 3, nine participated. In total, 29 nurses (all female), 9 nursing assistants (all female), 6 medical interns (3 male and 3 female) and 4 physicians participated in the study (2 female and 3 male) of whom one is general practitioner in the Emergency Department and three are obstetrician gynecologists. Of the 49 participants, 43 are women and six are men.

The most relevant results obtained throughout the process in meeting the objectives of the study are presented below, organized under the general categories defined in the objectives and the emerging themes derived from the analysis process.

Expectations regarding male partner participation in PCP

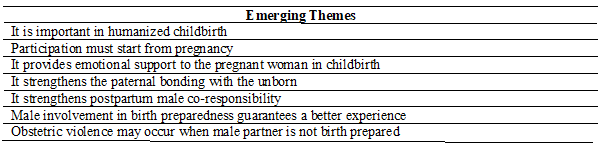

The participants were initially asked about how they see the male partner involvement in PCP. This question was due to the interest of revealing the expectations generated in them by the implementation of this strategy. This is how points of view in favor and some critical observations were known to be considered in its implementation. Table No. 2 summarizes the most prominent issues that emerged in this regard.

The findings show that there is acceptance of male partner participation in PCP by the health team members and recognition of its relevance within humanized childbirth, although for having acceptability this strategy must be continuous and mediated by prior education for men. One of the Obstetrician gynecologists interviewed in the study presents her vision in this way:

Everyone knows that this hospital is known by humanized delivery care. From the point of view of our work, one of the norms that we have here is humanized delivery, which helps male partners to participate (…) I would tell you that 80% of the women come to the ultrasound control with her husband. In childbirth, there is a stress factor, so one helps men: do you feel well? Do you want to go into labor? We are doing that feedback, assessment by assessment. (H3G1)

A reiterative issue, when the participants refer to male partner inclusion in PCP, refers to the importance of his accompaniment being present throughout the entire process, from the beginning of the pregnancy. It strengthen father-child bonding and male co-responsibility in the newborn care. Let us look at the point of view of a nursing assistant:

Accompanying is important from the moment you find out you are pregnant until the day of delivery. This serves as support and as father-child bonding. In addition, it can facilitate a pleasant childbirth experience. Finally, men could become more involved at home by helping to bathe and dress the baby. (H2A1)

The different specialty groups agreed that the male partner participation provides emotional support to the pregnant woman during childbirth, as explained by one of the medical interns:

In fact, it´s called humanized childbirth (...) It is something important because women, above all, feel intensely their partner support. We, the doctors, are usually pending to attend the birth and what their partner does is giving emotional support. (H2I1)

In the postpartum period, the partner's support for the woman is also considered important, given her vulnerable conditions, as stated by one of the medical interns:

In the postpartum, the woman comes out delicate, weak. If she is alone it is more risky for her and the baby, it is already more difficult to take care of herself and the baby at the same time. (H1I1)

Male involvement in birth preparedness guarantees a better experience, according to several of the participants. This is how one interviewed general practitioner expresses it:

The one who arrives having participated in preparation course for maternity and paternity, comes with everything clear, knows very well that we are going to take two hours, that he has to help in labor with all the techniques that have been taught, whether spontaneous or induced. So obviously, that makes it more beautiful. (H2M1)

While recognizing the importance of including men in PCP, two of the participating obstetric gynecologists describe situations that may involve obstetric violence to pregnant women by their partners during childbirth. They see this situation associated, not only with naturalized women violence in the contexts from which they come, but above all to the lack of prior preparation of men to participate as companions during birth. This was told by one of them:

We are facing many patients who are victims of social violence. Many extrinsic factors and emotional factors lead women to become a victim of obstetric violence within the childbirth process. If the man is not prepared, he can experience shifting from living something emotionally pleasant to becoming something emotionally pleasant to becoming in something that leaves a bad memory and that in certain moment becomes an emotional factor that instead being positive could be against his couple. (H1G1)

In an interview with one of her colleagues, this professional point out the following:

They have little tolerance to see their partners stressed, in pain or screaming (…) Many times, we had to take them out. They scold them; they slapped them in front of us. As many are older than they are, they are adolescents, sometimes they yelled them (…) you have to educate them, having a talk, showing a video, explain what is going to happen because they do not know. (H3G2)

Strategies to facilitate male participation in PCP

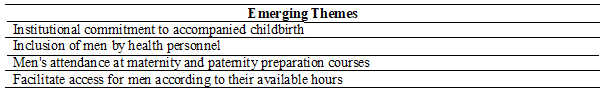

Health team members were asked about those strategies that could facilitate the involvement of men in PCP. The received responses are organized according to emerging themes in Table No. 3:

A first thing that stands out in the participants’ contributions is related to the subnetwork regulations establishing the humanized childbirth strategy, which strengthens male partner participation in PCP. The institutional commitment in accompaniment to pregnant woman during childbirth turns out to be one of the key aspects for facilitating male involvement un PCP, as reflected in the point of view of this general practitioner:

Here, the accompaniment during delivery is a plus factor. Ideally, the program is designed so that the first person who is the companion is the patient male partner (…) we have seen a good response from the men, from the patient partners, in being involved in the childbirth. (H2M1)

The attendance of men in maternity and paternity preparation courses is seen by the participants as an essential opportunity to clear up doubts and fears and to strengthen the emotional father-child bonding which brings them closer to the PCP process, as expressed by one of the nursing assistants:

Men ask many questions in the workshops; they say that they lack the necessary education; they say that the course has created in them not only awareness of the financial support but also emotional love for the child. (H2A3)

Not in all cases, men who wish to do so can be part of the childbirth preparation processes due to their work commitments and the teaching timetable. Facilitate them the access to educational processes taking into account their schedules is another aspect that the participants frequently mention. These are the words of a nurse:

I think there should be special sessions maybe on Saturdays because from Monday to Friday they are working. Therefore, if it could be done for example on Saturday it would be good. (H1E1)

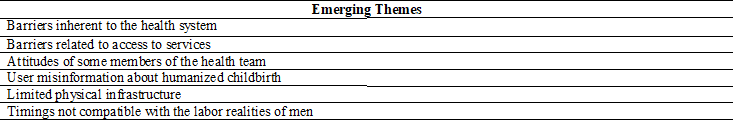

Barriers to male partner participation in PCP

When analyzing the barriers exposed by the participants, it was observed that these correspond particularly to two categories: cultural barriers and institutional barriers, which are described below.

Cultural barriers

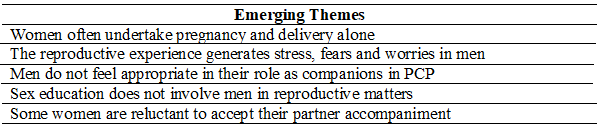

Table No. 4 shows the emerging themes related to the cultural barriers that make it difficult for male partner to participate in PCP.

A good part of the cultural barriers described is framed by gender differences and inequalities. The participants in the study mentioned in the first place that men are often absent in the reproductive processes, which are assumed by women alone, as explained by one of the interns:

It is sad because usually the patients we serve are low-income or migrant, and it is common to see that there is not the father in the entire process of pregnancy or delivery, either, I think it is extremely important because it is emotional support for woman. (H2I1)

It also happens, according to the information obtained, that men show fear of getting involved in reproductive care and do not feel appropriate to the role of companions of their partners, as related by one of the nursing professionals:

It scares them; they don´t really know that in the preparation courses they get all the information. They are afraid to enter an entity, the woman asks more than the man does; they do not talk much. (H1E2)

The emotional condition observed in men before the imminence of labor is described in this way by a nursing assistant:

It is very complicated for them to enter, they become nervous, they do not know what to do, and they are waiting. (H1A1)

Often men's fear of the experience limits their integration into the reproductive process, as one of the nurses put it: They fear to see their wives suffering. What would help is that they know that this is normal, that they know what can occur that is part of a process during labor. (H1E1)

One of the medical interns interviewed describes the situation that can be created in the pregnant woman due to her partner's reluctance to accompany her during childbirth:

Sometimes the mother wants the father to go into the delivery room, so that they can live the experience together, but when but when asked the father his for his signature to enter, he did not want to, he said he did not want to enter. Then the mother began to feel emotionally affected. (H1I2)

Excluding male from educational processes and sexual and reproductive health care limits their empowerment to participate in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum according to several of the study participants. This is how one of the nurses expresses it:

Men have been neglected in sexual and reproductive health programs; everything is aimed at women. In addition, I told the Secretary of Health: "We must strengthen male child growth and development, young men consultation, because from there we begin to improve." (CE1)

Accompaniment is a right of the pregnant woman and she may prefer a different companion than their partner in the childbirth process, as another of the nurses explains:

The whole issue of humanization is very important and it is not only that the couple enters, but that the woman decides if she wants him to enter. Because if she is not happy with her partner and feels safer with another person, her mother, for example, so let the person decide with whom she feels better for her support, not just the partner. (CE2)

It is also described that some women feel ashamed of being seen by their partners during childbirth, as explained by one of the nursing assistants:

There are women who say that they do not want their husbands to see them because they feel embarrass. They prefer a woman to enter with them; a woman gives them more confidence. (H3A1)

Institutional barriers

The most relevant emerging issues that are related to institutional barriers that limit male partner participation in PCP are presented in Table No. 5.

The healthcare system does not usually include men in reproductive care; there is a centrality in women, as stated by the nurses. Let us see one of the opinions:

I do not even see that in those clinical management guides men interact with care, I do not hear that they are included. Everything is the pregnant woman, the pregnant woman, the pregnant woman and all the guides and services are directed as if she were an individual patient and she has no one else. (CE1)

Certain barriers to access to services are mentioned among the male partner limitations in PCP participation, as highlighted by a nurse:

Sometimes the promises made in the childbirth preparation course are not kept. They do not allow the male couple attend their child's delivery and this person transmits the voice to voice, which makes the process difficult. (H2E2)

Although progresses are recognized, there is still a lack of will from some medical professionals, resulting as a limitation described by another of the participating nurses:

The biggest obstacle were the medical doctors; it was very difficult that they allowed fathers to enter. Although little by little they became more open, not everyone agreed. (CE3)

An aspect frequently mentioned by the nurses is related to misinformation to users. Sometimes information lacks, so men do not know that the humanized birth model is implemented in institutions, as one of them points out:

Many of the fathers when we do the postpartum follow-up say that they had no idea that it was a humanized birth institution because nobody informed them. (CE4)

The unsuitable scenarios due to the inappropriate infrastructure represent another difficulty for men to participate in childbirth in hospitals, as highlighted by one of the obstetrician gynecologists:

I think that here we lack privacy; we have a collective delivery room where the only thing that separates one patient from another is a curtain and there really is not space available and suitable for the family member where he can be. (H1G1)

The need of larger spaces allowing better access possibilities is exposed by one of the nurses:

The delivery rooms are required to be larger because at times there is no space (...) it would be ideal to have an area where it is marked "this is for humanized delivery." (CE5)

Institutional schedules that are not compatible with the realities of men as workers make their access difficult at different times in the process. For example, these limit their participation in the preparatory courses for maternity and paternity required in one of the hospitals to access delivery, as highlighted by another of the nurses:

The (obstacle is the) schedule regarding attendance at the maternity preparation course because this is a requirement for the father to enter the delivery. Therefore, the schedule makes it difficult. (CE2)

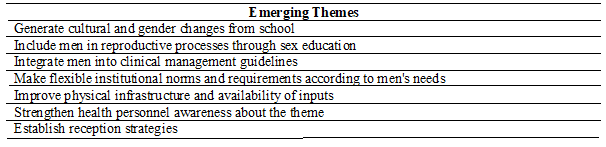

Proposals for change

In order to improve the situation and strengthen the male partner participation in PCP, the health team members present several proposals that are collected as emergent themes in Table No. 6.

The need to create structural changes through culture and through sexual education so that men take ownership of reproductive health is an aspect that is mentioned among several of the participants as expressed by one of the nurses:

Changes in culture since adolescence. Sexual health was left to the teachers and I think that this is wrongly focused; it should have been left to the health professionals. Then it must start from the time the teen boy begins birth control. (CE1)

Along the same lines and focused on school education is the contribution of an intern:

With children from the eighth grade onwards, when they have reached the use of reason, as well as we talk on contraception, we could talk about childbirth accompaniment. (H2I3)

As seen previously, some participants have shown that male partners are not included in the clinical guidelines for maternal health management. Including them is one of the options proposed by another of the medical interns:

The PCP clinic management guides do not talk much about male participation, it would be (useful) to integrate them so that there will not be excuses to avoid it, seriously showing and evidencing that comprehensive management can being done. (H2I4)

Strengthening awareness and training processes to medical and nursing professionals for the humanized childbirth management appears as one of the relevant options for improving the male partner participation in PCP. This is how one of the nurses expressed:

Despite the fact that in 2018 the humanized birth process came out, we see that there are professionals who still fall short, they do not know what it means, how they do it, we also see that it depends on the professional on duty. There are some nurses who are sensitive to humanization, who fight with everyone to get the family member to have these humanizing moments, but there are others whose workload does not allow them to carry out the entire humanization process. (H2E5)

This is the point of view of one of the medical interns, who insists that professionals have to motivate men to be part of the PCP:

We need to know the importance of that and we need to know how remarking it at the time of our consultations or at the childbirth. That is something super important because in a certain way we have an influence on the patient. (H2I4)

Having supplies that can facilitate the entry of men, such as gowns and masks, could help to include them in childbirth and immediate puerperium, as highlighted by a nurse:

Gowns are very important supplies; surgical dress so that they can enter; because when we make them buy these dresses, many dads cannot afford them and have not a way to participate (…) the institution must strengthen this process at the administrative level. (H2E5)

Always comply with the institution's commitment to the men who have carried out the process, to avoid the lack of credibility in humanized delivery, is also part of the proposals. This is how one of the nurses explains it:

In one course, a man said "no, they won't let us in" and of course there were all the few that accompany pregnant women (...) It is a very complex scenario, very difficult, but it would be necessary to look at how to meet that 5% who are committed because they are very few. (CE7)

Timely involving and educating men to be part of the process is another aspect that is mentioned among the alternatives, as one of the obstetrician gynecologists does during the interview:

We need to be able to face this situation when man wants to enter and his right must be respected, but also prepare him to do in the way it should be. A man who participates in this process has to be involved in a timely manner, within the pregnancy, in the prenatal control, and not to come to an unexpected context where he will not be prepared for certain stress and emotional factors. (H1G1)

This same professional suggests preparing men as a particular group:

If the man is prepared to face the process, even in scenarios different from where pregnant women are prepared, he enters with a very different profile and with a very mature perspective. (H1G1)

It is proposed to eliminate barriers at the level of the subnetwork institutions and, as one of the key aspects, to generate adjustments such as having more affordable schedules allowing men to participate and go to services. This is how one of the nurses expresses it:

Having more affordable scheduling for courses, consultations and visits. Little by little, we are maturing that idea and the goal is that the patient has support all the time. (CE7)

Another aspect mentioned is the preparation of men to assume an active role in the postpartum period, as suggested by one of the medical interns:

In the activities, teaching to fathers how to hold a baby, how to take care of it, how to change a diaper, how to make a simple feeding bottle because they do not know how to do that. (H2I4)

Using communication strategies to offer information to couples on humanized childbirth is another of the proposals made, as this nurse did:

Information channels should be stronger. From the moment they arrive let men know this: “Here you can have humanizing moments.” (H2E6)

Implementing technology to strengthen information and communication with users is an aspect in which the different approached groups coincide, as expressed by this nursing assistant:

The subnetwork must use its technological resources for transmitting the information.

Eliminate barriers, reporting in different ways and taking advantage of resources. (H1A3)

Finally, one of the nurses calls for the flexibility of the health professionals of the subnetwork to facilitate humanization and male partner inclusion in the reproductive process in different ways:

It may be that the man does not enter at the time of delivery, but enters the neonatal adaptation, or enters at the time of labor or simply the man works, he cannot come during the day and arrives at 10 at night because of is the only time he has to visit his wife who is in labor. We must allow him to enter. (CE7)

Discussion

The inquiry process carried out allows us to offer important inputs for strengthening the male partner participation in PCP within the context of humanized delivery in the three hospitals that belong to the health subnetwork where this study was carried out and in other institutions with similar conditions. Contrary to what has been found in the literature, which reports little receptivity from health personnel towards male partner participation in PPE (6, 9), the different members of the health team consider this strategy in a favorable way, which speaks of a resolute work for the consolidation of humanized childbirth in the analyzed institutional context. However, there are critical aspects to be resolved and necessary adjustments in the strategy implementation to fulfill its mission, guaranteeing accessibility, acceptability and opportunity as required and helping to generate transformations in the experiences of men as partners and as parents, considering the importance of strengthening the gender equality. As a strength, the commitment of the hospitals in the subnetwork to humanized childbirth is observed which is consolidated in a normative way, being considered central by the participants for the proper course of the male partner inclusion in the reproductive processes. As stated by Mullany and his colleagues 11, the favorable attitude of staff and users towards the inclusion of the male partner in PCP may depend on institutional will.

Among the positive aspects of the male partner participation in PCP, the different actors linked to the study especially remark its favorable impact on the emotional situation of the pregnant woman. Some studies have reported this evidence. Ramirez Pelaez et al. 23, in a review study, found that male partner participation reduces worries, improves feelings of self-control, and minimizes rates of postpartum depression in pregnant women. At birth, partner with prior training accompanying reduces the anxiety of the pregnant woman, so it is recommended to consider this intervention 24.

Cultural and institutional barriers associated with the exclusion of the male gender from reproductive processes appear in the analyzed narratives: sexual education does not empower male to be part of these processes and the health system itself makes them invisible. Several of the obstacles and limitations for men to participate in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum are structural, given the social regulations that have naturalized and delimited the roles and responsibilities for men and women (10, 24, 25). In reproductive context, there are frequently cultural barriers associated with gender that reflect a structural inequality distancing men and women in the world of care, regarded as feminine 10.

According to some participants, cannot be observed the inclusion of the male partner in the clinical guidelines derived from national maternal health policies since those are focused on pregnant women. In Colombia, studies do not show that health systems take into account men access or consider the male perspective in sexual and reproductive health 26. Health policies and services tend to focus on the needs of women, which limits the participation and identification of men's needs 27.

The lack of male accompaniment to the pregnant women in the pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care is mentioned among the participants as a reality that is often observed. In addition to aspects associated with working life that can exclude men from these processes 11 and their unfamiliarity with PCP 9, it should be remembered that in Colombia the number of women head of household exceeds 35%, according to the latest National Household Survey of the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) 28. In front of pregnancy, evasion of male responsibility is still frequent. In this reality, unwanted pregnancy and adolescent pregnancy carry an important weight 29.

Among the institutional barriers, those related to infrastructure are a priority for the participants in the study, to which is added the lack of will of some members of the health team. Caceres and Nieves 34 state that sometimes health personnel members propose actions to achieve humanized care during childbirth, but they encounter difficulties such as infrastructure deficiencies, work overload, weaknesses in institutional organization, and lack of interest in some members of the health team. Given the importance of continuing to generate a paradigm shift at the institutional level, it is necessary to make awareness among members of the health team a permanent process. Determined work to strengthen the required physical infrastructure is necessary in the subnetwork.

As highlighted by several participants in the study, Maroto and colleagues 32 found access problems due to incompatibilities between the schedules of services offered during pregnancy and men's working timetable. Figueroa 33 reports that this barrier is a reality that men often face when they want to be involved in PCP processes. Given the limitations related to the available time of men to access the preparation courses for maternity and paternity and the maternal services, repeatedly mentioned throughout the study, it is important to analyze this circumstance. In addition, looking for solutions is necessary because an institutional barrier like this can undermine the different efforts that can be made to include men in PCP. It is necessary to open the way and make the necessary adjustments to enable the male partner participation in an active, conscious and informed way throughout the gestational process and to build viable and high-impact strategies that prepare them to live with awareness a process that is significant for them and for their partners and children lives. As already stated, the lack of preparation for this experience limits the possibility of a positive participation in the PCP for them.

Several of the interventions refer to men's interest in participating and the need to inform them more efficiently about existing options. It is important to recognize that communication and information are the gateway to participatory processes for users, and that at this point it is important not only to inform but also to recruit. Men interviewed in Granada, Spain, see the role of health services as important in strengthening their interest in participating and not excluding those who want to be there. They consider it the responsibility of the services to bring them closer and help them to be linked to the processes. In the humanized childbirth, communication acquires a social and therapeutic value. To be successful in this model, efficient communication is required 32).

A sensitive aspect that appears in the study is related to the lack of conditions of some men to participate in childbirth, associated with the abuse of women that is naturalized in their contexts and with their lack of preparation to understand the particularities of childbirth. These circumstances can even lead to obstetric violence situations, so the importance of men preparation to participate in PCP is stressed. It is noted that gestation allows educational processes toward men that can go beyond preparing them for their role in childbirth. These processes need to be designed considering masculinity perspective, to generate changes in men as highlighted by Figueroa 33 who observes that fatherhood represents an important turning point in the construction of new masculinities, leaving behind negative ways of building as men. This, in line with the World Health Organization 7, which considers that the intervention of the couple in the reproductive processes is desirable as long as it corresponds to the autonomous consent of the pregnant woman, is aimed at offering support and is mediated by processes of men preparing for birth support based on gender equity.

Finally, it is important to highlight the importance of the health team members being trained to implement gender-sensitive strategies. It has to be centered in a critical perspective towards the construction of hegemonic masculinities, leaving behind the idea that the central role of men in PCP processes is of an economic nature and calling for new forms of relationship between men and their partners and their children. The breakdown of the hegemonic model of masculinity occurs precisely where men are involved in caring processes. Health personnel is called upon to break the mold, leaving behind stereotypes and prejudices, for which it is necessary for the team members having training process that allows them to assume positions that contribute to the construction of new masculinities, considering that the reproductive processes are an important setting for this purpose.

Research limitations

Being a qualitative study, the findings obtained in this research cannot be generalized except to the human group that was approached or to groups with similar conditions. Reading the results requires contemplating the weight of the social and cultural context in which the participants operate. The limited time of the medical staff did not allow for a greater number of obstetrician gynecologists in the study, which would have enriched it.

Conclusions

At the structural level, education and health institutions have the important task of training for new masculinities and of advancing inclusive educational processes with men and empowering them in front of sexual and reproductive health, creating cultural and gender changes. It will encourage them to assume with greater ownership their role in the PCP and make transformations in the way of constructing themselves as men. For a paradigm shift favorable to their participation in PCP care services, it is necessary to eliminate access barriers of a cultural and institutional nature at the different levels of the health system.

In the three hospitals that constitute the subnetwork, there is a favorable context for male inclusion in PCP, which derives from the institutional commitment to humanized delivery. For greater achievements, it is necessary to adapt the infrastructure, minimize access barriers for male partners in the preparation and accompaniment processes in PCP, and continue working on sensitizing the health team. It is suggested to design innovative strategies for the recruitment, reception and education of men by implementing a gender perspective focused on masculinities. These strategies require contemplating their specific realities and needs and preparing them for a positive experience of parenthood and in the care of their partners and children, from the beginning of pregnancy, causing changes in gender equality. All this in harmony with women´s autonomy to decide and with their rights, which is the spirit of humanized childbirth.

REFERENCES

1.Organización de las Naciones Unidas. Conferencia Internacional sobre Población y Desarrollo, El Cairo: ONU; 1994. [ Links ]

2.Organización de las Naciones Unidas. IV Conferencia de la Mujer. Beijín: ONU; 1995. [ Links ]

3.República de Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (En línea). Política nacional de Sexualidad, derechos sexuales y derechos reproductivos. Bogotá, 2010. Disponible en: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/LIBRO%20POLITICA%20SEXUAL%20SEPT%2010.pdf [ Links ]

4.Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JECH (Revista en línea) 2015 (acceso sept. 03 de 2019). 69:604-612. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204784 [ Links ]

5.Aborigo AR, Reidpath DD, Oduro RA, Allotey P. Male involvement in maternal health: perspectives of opinion leaders. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (Revista en línea)2018 (acceso sept. 08 de 2019);18 (3): 1-10. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1641-9 [ Links ]

6.Lafaurie MM, Valbuena Y. La pareja masculina en el embarazo: perspectiva de gestantes atendidas en la Subred Integrada de Servicios de Salud Norte, Bogotá. Rev. Colomb. Enferm. (En línea)2018 (acceso 11 abril de 2020). (17): 46-55. https://doi.org/10.18270/rce.v17i13.2432 [ Links ]

7.Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la Organización Mundial de la Salud sobre intervenciones de promoción de la salud para la salud materna y neonatal. Ginebra: OMS; 2015 [ Links ]

8.Castrillo B. Análisis de la atención médica de embarazos y partos: aportes conceptuales. La Plata: Memorias II Jornadas de Género y Diversidad Sexual (En línea). 2016 (acceso oct.02 de 2019). Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/trab_eventos/ev.8180/ev.8180.pdf [ Links ]

9.Kaye DK, Kakaire O, Nakimuli A, Osinde MO, Mbalinda SN, Kakande N. Male involvement during pregnancy and childbirth: men’s perceptions, practices and experiences during the care for women who developed childbirth complications in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth(Revista en línea). 2014(acceso oct.02 de 2019); 14:54. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2393-14-54 [ Links ]

10.Laguado T, Lafaurie MM, Vargas LM. Experiencias de participación de los hombres en el cuidado a su pareja gestante. Duazary (Revista en línea) 2019 (acceso oct.02 de 2019); 16 (1): 78-92. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.21676/2389783X.2532 [ Links ]

11.Mullany B. Barriers to and attitudes towards promoting husbands’ involvement in maternal health in Katmandu, Nepal. Social Science & Medicine (Revista en línea) 2006 (acceso sept. 06 de 2019)62, (11): 2798-2809.Disponible en: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953605006052 [ Links ]

12.Hamui A, Varela M. La técnica de grupos focales. Inv Ed Med. (Revista en línea) 2013 (acceso sept. 06 de 2019); 2 (5):55-60. Disponible en: http://riem.facmed.unam.mx/sites/all/archivos/V2Num01/09_MI_HAMUI.PDF [ Links ]

13.De la Cuesta C. Estrategias cualitativas más usadas en el campo de la salud. Nure Inv. (Revista en línea) 2006 (acceso sept. 23 de 2019) 25. Disponible en: https://www.nureinvestigacion.es//OJS/index.php/nure/article/view/313 [ Links ]

14.Amezcua M. La entrevista en grupo. Características, tipos y utilidades en investigación cualitativa. Enfermería clínica (Revista en línea) 2003(acceso sept. 24 de 2019); 13 (2): 112-117. Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1130862103737917 [ Links ]

15.Troncoso-Pantoja C, Amaya-Placencia A. Entrevista: guía práctica para la recolección de datos cualitativos en investigación de salud. Rev. Fac. Med (Revista en línea). 2017(acceso nov. 05 de 2019);65: 329-32. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v65n2.60235 [ Links ]

16.Díaz-Bravo L, Torruco-García U, Martínez-Hernández M, Varela-Ruiz M. La entrevista, recurso flexible y dinámico. Investigación en educación médica. 2013; 2 (7), 162-167. [ Links ]

17.Paredes A, Castillo MT. Caminante no hay (un solo) camino al andar. Investigación acción participativa y sus repercusiones. Rev Colomb Soc. 2018; 41 (1): 31-50. [ Links ]

18.Canales M. Conversaciones para el entendimiento. En: Durston J, Miranda F. Experiencias y metodología de la investigación participativa. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL, 2002. [ Links ]

19.Martínez-Salgado C. El muestreo en investigación cualitativa. Principios básicos y algunas controversias. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva(Revista en línea); 2012(acceso oct.11 de 2019); 17 (3):613-619. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232012000300006 [ Links ]

20.Mieles BMD, Tonon MG, Alvarado SV. Investigación cualitativa: el análisis temático para el tratamiento de la información desde el enfoque de la fenomenología social. Universitas humanística. 2012; 74: 195-225. [ Links ]

21.Noreña AL, Alcaraz-Moreno N, Rojas JG, Rebolledo-Malpica N. Aplicabilidad de los criterios de rigor y éticos en la investigación cualitativa. Aquichan (Revista en línea).2012 (acceso jul. 05 de 2019); 12 (3): 263-274. Disponible en: https://aquichan.unisabana.edu.co/index.php/aquichan/article/view/1824/2936 [ Links ]

22.World Medical Association (WMA) (En línea). WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Fortaleza: 64th WMA General Assembly; 2013 (acceso mar.12 de 2019). Disponible en: https://bit.ly/2rJdF3M. [ Links ]

23.Ramírez Peláez H, Rodríguez Gallego I. Beneficios del acompañamiento a la mujer por parte de su pareja durante el embarazo, el parto y el puerperio en relación con el vínculo paternofilial. Revisión bibliográfica. Matronas profesión. (En línea) 2014 (acceso jul. 19 de 2019) Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5527090 [ Links ]

24.Salehi A, Fahami F, Beigi M. The effect of presence of trained husbands beside their wives during childbirth on women's anxiety. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. (Revista en línea) 2016 (acceso sept. 08 de 2019);21: 611-615. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/1735-9066.197672 [ Links ]

25.Aliabedian, A, Agajani, M, Khan, A. Iranian men’s attendance in pregnancy. Caspian J Reprod Med (En línea) 2015( acceso 02 abril 2020); 1 (3): 12-17. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289460834_Iranian_men's_attendance_in_pregnancy [ Links ]

26.Pinilla E, Forero C, Valdivieso MC. Servicios salud sexual y reproductiva según los adolescentes varones (Bucaramanga, Colombia). Rev Fac Nac Salud Pública (Revista en línea). 2009 (acceso 26 septiembre de 2019); 27 (2): 164-168. Disponible en: http://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/fnsp/article/view/327 [ Links ]

27.Ochoa-Marín S, Vásquez-Salazar E. Salud sexual y reproductiva en hombres Rev. salud pública (En línea). 2012 (acceso marzo 07 de 2020);14 (1): 15-27. Disponible en: https://www.scielosp.org/pdf/rsap/2012.v14n1/15-27 [ Links ]

28.DANE ―Departamento Nacional de Estadística―. Encuesta Nacional de Calidad de Vida -ECV 2015. Boletín técnico (En línea) 2015(acceso 11 abril de 2020). Disponible en: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/condiciones_vida/calidad_vida/Boletin_Tecnico_ECV_2015.pdf [ Links ]

29.Lafaurie MM. Violencia de la pareja íntima en relatos de gestantes atendidas en el Hospital de Usaquén (Bogotá, Colombia). Rev Colomb Enferm. (En línea) 2015( acceso 11 abril de 2020).; 11 (10): 45-56. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.18270/rce.v11i10.738 [ Links ]

30.Hildingsson I, Haines H, Johansson M, Rubertsson C, Fenwick J. Childbirth fear in Swedish fathers is associated with parental stress as well as poor physical and mental health. Midwifery (Revista en línea) 2014(acceso 11 abril de 2020); 30: 248-254. Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0266613813003598 [ Links ]

31.Philpott Ll, Fitzgerald S, Leahy-Warren P, Savage E. Stress in fathers in the perinatal period: A systematic review. Midwifery. (Revista en línea) 2017(acceso 11 abril de 2020); (55): 113-127. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.09.016 [ Links ]

32.Maroto Navarro G, López E, Calvente M, Ruzzante N, Rodríguez I. Paternidad y servicios de salud: Estudio cualitativo de las experiencias y expectativas de los hombres hacia la atención sanitaria del embarazo, parto y posparto de sus parejas. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica (En línea). 2009 (acceso 12 septiembre 2019); 83 (2): 267-278. Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272009000200010&lng=es [ Links ]

33.Figueroa JG. Algunas Reflexiones Metodológicas al Abordar Experiencias Reproductivas de los Varones desde las Políticas Públicas. Masculinities and Social Change, 2016. vol. 5, no. 2, p. 136-155. [ Links ]

34.Cáceres-Manrique FM, Nieves-Cuervo FM. Atención humanizada del parto. Diferencial según condición clínica y social de la materna. Rev Col Obstet Ginecol. (Revista en línea) 2017 (acceso 07 abril 2020); 68 (2): 128-134. DOI: Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.18597/rcog.3022 [ Links ]

How to cite: Lafaurie-Villamil,M.M., Valbuena-Mojica, Y. Male partner participation in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: health team members´ perceptions in Bogota. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2020; 9 (2): 129-148. Doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v9i2.2288

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M.M.L.V. has contributed in a,b,c,d; Y.V.M. in b,c,e.

Received: May 19, 2020; Accepted: August 26, 2020

text in

text in