Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versão impressa ISSN 1688-8375versão On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.9 no.1 Montevideo 2020 Epub 01-Jun-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v9i1.2147

Original Articles

Mapuche mothers 'lives during the hospitalization of their children, in a high complexity hospital in southern Chile

1 Departamento de Enfermería, Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile

2 Hospital Hernán Henríquez Aravena. Temuco, Chile edith.rivas@ufrontera.cl

Keywords: transcultural nursing; indigenous population; mothers; hospitalization

Palabras clave: enfermería transcultural; población indígena; madres; hospitalización

Palavras chave: enfermagem transcultural; população indígena; mães; hospitalização

Introduction

Nursing is a discipline characterized by important ethics training, social commitment and its holistic nature. As such, it has a duty to generate knowledge in the area of intercultural health, which contributes to developing and strengthening the work in accordance with the Ministry of Health’s strategies. The Ministry of Health (MINSAL) prioritizes reducing inequality gaps in indigenous health through the participatory building of health strategies at the level of health services and regional ministerial secretariats (Seremi) 1. Thus, diversity is recognized, the complementarity between medical systems is promoted and adequate health services are provided that respond to the needs, rights and epidemiological profiles of this population 1-3.

At present in Chile, the Special Health and Indigenous Peoples Program operates within the Health Services of almost the entire country with emphasis on places with the highest concentration of indigenous populations. The participation of indigenous peoples in the design, implementation and evaluation has been a key strategy, and is grouped into three components: (a) equity, (b) interculturality and (c) participation. Equity seeks to contribute to reducing the existing gaps in access to prompt, quality health care by improving the accessibility, quality and cultural relevance of the services provided through intercultural facilitators and cultural advisers in the service network, intercultural offices and intercultural signage mounted in health care centers to orient indigenous users. The intercultural health approach incentivizes the training and development of health care teams that can respect, understand and respond appropriately to the proposals and needs of indigenous communities and organizations related to the topic of health. The third component of the program seeks to promote the participation of indigenous peoples in the planning, implementation and assessment of strategies designed to improve their state of health 4-5. The theoretical referent for this study is Madeleine Leininger’s Theory of Cultural Care, Diversity and Universality 6.

The social significance of the study is related to the strategic objective of the inequities among indigenous peoples 3; therefore, it is relevant and necessary for nurses to know the experience of the indigenous peoples, considering the implemented policies. Therefore, a qualitative study is proposed with an ethnographic approach, with the question: What is the experience of Mapuche mothers during the hospitalization of their children in pediatric services in a hospital in southern Chile? The purpose is to contribute to nursing knowledge in the area of intercultural care.

General objective

To reveal experiences of Mapuche mothers during the hospitalization of their children in a high complexity hospital in southern Chile in 2018.

Materials and methods

A qualitative study was conducted that addresses a focused ethnography. It approaches a phenomenon as a group experiences it in a certain context, examining experiences within a culture in particular surroundings 7-9. This method enables an approach from the participants’ point of view, or from the emic view, but in a very specific sense with respect to certain situations, activities and actions 10.

Unlike the classic ethnography based on experience, focused ethnography is short-range and not continuous, so it can be used to investigate phenomena that involve short-term field visits, as occurs with hospitalized patients. It is characterized by the high level of analysis required, use of technologies, notes, transcriptions and encoding and sequential analysis 10.

The proposed inclusion criteria for this study were: mothers who speak Mapudungun (Mapuche language) with children hospitalized in pediatric services in a high complexity hospital, who agreed to give a recorded interview after signing an informed consent form. The sampling was intentional, considering the cases available according to the inclusion criteria. With this in mind, there were 9 participants. Data were collected by participant observation, in-depth interviews with the respondents during the period of hospitalization of their children and field notes from the observations and interviews. With respect to the interviews, these were recorded and transcribed textually by the investigators themselves. The information collected through the accounts were analyzed immediately until reaching data saturation, i.e., until no new data were obtained and their analysis became redundant. From the information provided, the codes and analysis categories were determined, selecting the significant texts based on the thematic approach, in search of expressions referring to the mothers’ experience during the hospitalization of their children.

Investigator triangulation was used, so that the principal investigator and co-investigators performed the analysis independently and then shared, finding some differences; therefore, a re-reading and a new analysis took place, ultimately reaching consensus. Thus, one metacategory and four intermediate categories emerged.

The rigorous criteria used were Guba and Lincoln’s dependability, credibility, confirmability and transferability 11. Ezekiel Emanuel’s ethical principles in research involving human beings were respected 12.

Results

The results were obtained by collecting the data through participant observation, field notes and in-depth interviews with 9 key informants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study after signing the informed consent. 18 interviews were conducted with an average of 60 minutes each.

All the participants lived in the Region of La Araucanía, Chile, aged between 32 and 36 years, 5 of whom had an incomplete elementary education, 3 complete secondary education and 1 complete higher education.

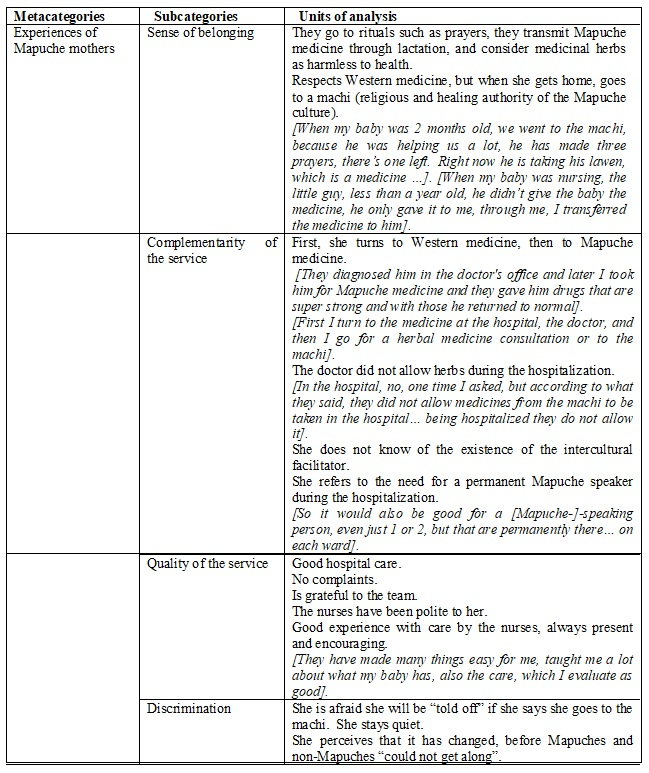

After the analysis, the metacategory emerged - experiences of Mapuche mothers - and the following subcategories were identified: sense of belonging to their culture; complementarity of care, quality of care and discrimination. (Table 1)

Discussion

The experience of Mapuche mothers is permeated by a strong connection the culture of origin, and it is noted that they turn to Western medicine, but adherence to it is not followed in the participants’ accounts, which could show a certain distrust of Western medicine. Although complementarity emerges in the experience from both types of health care, the participants require the attention of Mapuche medicine to satisfy their health needs. In the experience “quality of care”, although absolute approval of the care is noted, this can be masked by the posture that participants adopt when faced with Western medicine. Finally, the experience “discrimination” is expressed as the fear of valuing their culture, maintaining a passive position.

With respect to sense of belonging, the participants recognize that they turn to the prayers and rituals of the Mapuche culture. They indicate respect for Western medicine, turning to it first and then resorting to Mapuche medicine, which on many occasions gives them greater confidence, while at the same time they consider natural medicinal herbs to be harmless to human health. What stands out is that they go to Mapuche medicine not only to address their personal health problems, but also for their children, passing on Mapuche medicine through lactation. These results agree with another Chilean study proposed by Ochoa et al. 13 that addresses the perceptions of urban indigenous users of the public health care system, describing the participants as turning to health services first, although with less confidence in the healing results and only to rule out a serious disease. Greater confidence is manifest in the effect of herbs, which are perceived as less invasive for the body. Indigenous users, although they recognize the work of Western medicine, have a sense of distrust towards it 14-15 and also consider that the practice of Mapuche medicine acts to their benefit in a comprehensive way, since they link people’s physical and spiritual well-being, and its practice in urban contexts enables the ethnic identity to be maintained as well as being the core of cultural transmission 13. In this vein, a Colombian study presents the high attendance of users, the confidence of the patients, the easy accessibility and affordability, the human quality, the reduction of costs and the satisfactory control of diseases as achievements of indigenous traditional medicine 16.

In complementarity of care, the participants state that the first consultation is with Western medicine, and then they turn to Mapuche medicine in a complementary way; however, during hospitalization this is not expressed due to the social pressure exerted by institutional regulations. Ignorance of the existence of intercultural facilitators exacerbates the situation, which is why the complementarity of the two health systems cannot be visualized in the care offered to patients during their hospitalization despite the policies implemented to promote interculturalism in health centers 2. Also, in the training of health professionals in Chile, only one university has incorporated the topic of intercultural health in its curriculum and only for the nursing program. Other institutions of higher learning include this approach in the objectives of their programs, although its development as a concept and a practice is insufficient 17. This situation is troubling because the development of an intercultural health approach supposes, among other things, the training and development of health care teams capable of respecting, understanding and responding to the proposals and needs of indigenous communities and organizations on the subject of health 18-19. In this respect, Ochoa et al. 13 reports that the coexistence and dialogue between the two types of medicine is currently recognized, but at the same time the health team and civil servants are unable to incorporate the demands of the indigenous patient in the process and public care spaces or to understand and legitimize the cultural diversity, knowledge, beliefs and practices of the indigenous world in Chile.

Another aspect of the experience is quality of care, which has been described as positive, so that the participants express their gratitude and value the work of the health team in the care of their children, as well as the education interventions offered by the nurses, with whom they established a supportive relationship. Considering that interculturalism in health is a tool to improve access and quality of care 14, Chile has launched several strategies for the incorporation of the intercultural approach in health programs, suggesting the improvement in quality of care through the treatment of user, schedule adjustment and cultural relevance in health care through the equity component 1. However, despite these policies, in this study it is observed that the public health model shows deficiencies in serving the current demands and reality of the indigenous population in hospital centers in the Region of La Araucanía, and it is worth highlighting that this is not expressed in the experience of quality of care, an aspect that can be masked by the attitude the participants adopt when dealing with Western medicine. On the other hand, deficiencies in the quality of care have been reported in other studies. In a Bolivian study it was concluded that indigenous women who rejected institutional childbirth were motivated by the deficient quality of care in the health centers, because they were victims of derogatory and degrading expressions about themselves and their native health practices 20.

In close relation to this, the experience also involves discrimination, an aspect that is demonstrated with the manifestations of fear of expressing and recognizing that they turn to Mapuche medicine, since some type of negative feedback from Western medicine is perceived that makes them afraid. The participants’ fear of expressing the knowledge and practice of Mapuche medicine doubtlessly reflects once again the inability of the public health model to incorporate the demands of the indigenous patient, as expressed by Ochoa et al. 13, who also show that the indigenous population undergoes negative experiences in health care, including poor treatment, discrimination practices, scarce access to medical appointments and treatments, bureaucratic obstacles, deficient user/professional relationships, and others. This situation is also expressed in international studies, which describe the existence of poor treatment and discrimination of the indigenous population exercised by the health personnel, who should ensure patients’ physical, psychological and spiritual well-being 16. As a result, these practices produce fear and distrust towards health workers, who with their acts create a barrier that makes it difficult for the indigenous population to seek the care they need in the health system 21.

Accordingly, it is necessary for the health team to achieve greater understanding of the diversity, cultural and social dynamics in which indigenous users are embedded, even more those health professionals who work in areas with a high concentration of native population, sectors where a team is required that can respect, understand and respond to the proposals and needs of indigenous communities and organizations in order to offer culturally consistent care 21-22. Far from this reality, today “cultural blindness” is spoken of in health professionals, where there is a lack of cultural knowledge and unawareness of it, which prevents nursing practice from offering care with “cultural coherence” 23-24. However, in recent decades nurses have increased their interest in including culture in health services, also influenced by migratory trends, which is why today they are more aware of the need to acquire cultural competence, which helps them establish therapeutic relationships through understanding of the culture, thereby strengthening health care practice 25-27. It should be noted that cultural competence is an ability that is developed gradually and seeks to offer safe and quality health care to users of different cultural origins, with definitive attributes being cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, cultural knowledge and cultural skill 26-28.

From the theoretical point of view, Madeleine Leininger’s Theory of Cultural Care, Diversity and Universality supports the results from the mothers’ concepts of culture and values (beliefs about health, disease and behavioral model). The consistency of culturally pertinent (beneficial and effective) care is revealed and the transcultural knowledge in the mothers’ decisions and actions is explained. Finally, this study endeavors to highlight cultural care as a holistic theory, which considers human life in its fullness as well as the factors of the social structure, cultural trajectory, context of the surroundings and linguistic expressions 6.

Conclusions

An ambiguous experience is noted in the mothers, and one of its key elements are the developmental patterns that respond to a logic of cultural, spiritual and social knowledge. Also, complementarity is a challenge that requires an understanding of the intercultural contact around dialogue and respect for diversity. Another element is the intercultural pattern referenced from the culture of both worlds.

Descriptively, a certain vagueness can be seen in the sense of belonging to Mapuche and Western medicine due to greater confidence, high level of attendance, accessibility, affordability, good human quality and lower costs initial costs of Mapuche medicine 16.

At the same time, setbacks, disappointments and complications are noted in legitimizing social and cultural diversity, which impedes the success of the cultural coherence strategies in health as discriminatory features emerge. The comprehensive nature of the indigenous world is manifest in the people through the expression of their cultural values. Likewise, it is observed that the public health model is anachronistic in serving the current demands and reality of the indigenous population, since it perpetuates a relationship with a lack of communication between Mapuche user-health care teams.

Suggestions: The deficit in training for health care teams in terms of intercultural health is a concern given that the success of this practice requires professionals and technicians able to respect, understand and respond appropriately to the proposals and needs of the indigenous population. The inability of the health care team to incorporate the demands of the indigenous patient has an impact on legitimizing cultural diversity, cultural competence, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, cultural knowledge and cultural ability for safe, quality health care. In this aspect, nursing must lead and position itself in the cultural care approach to achieve greater understanding of diversity as a human phenomenon, where care must be expressed with openness, kindness and generosity, which are key elements for safety, confidence, acceptance and collaboration in health care.

REFERENCES

1. Cheuquepán, S, Henríquez, J, Bustos, B. Orientaciones Técnicas Programa Especial de Salud y Pueblos Indígenas. Guía Metodológica para la Gestión del Programa. (Internet). Chile: Ministerio de Salud; 2016 (acceso 17 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en:Disponible en:http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/030.OT-y-Guia-Pueblos-indigenas.pdf [ Links ]

2. Ministerio de Salud. Norma General Administrativa N° 16, Interculturalidad en los Servicios de Salud. (Internet). Chile: Ministerio de Salud ; 2006 (acceso 17 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.minsal.cl/sites/default/files/files/Norma%2016%20Interculturalidad.pdf [ Links ]

3. Gobierno de Chile. Estrategia nacional de salud para el cumplimiento de los Objetivos Sanitarios de la Década 2011-2020. (Internet). Chile: Ministerio de Salud ; 2010 (acceso 12 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/c4034eddbc96ca6de0400101640159b8.pdf [ Links ]

4. Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales. Informe de Descripción de Programas Sociales. Programa Especial de Salud y Pueblos Indígenas. (Internet). Chile: Ministerio de Salud ; 2016 (acceso 12 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.programassociales.cl/pdf/2017/PRG2017_3_59209_2.pdf [ Links ]

5. Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales. Programa Especial de Salud y Pueblos Indígenas. (Internet). Chile: Ministerio de Salud ; 2013 (acceso 12 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.araucanianorte.cl/images/PDF-WORD/Resol.Ex-N-20-del-17.01.2013-Programa-PESPI.pdf [ Links ]

6. Leininger, MM. Teoría de la diversidad y de la universalidad de los cuidados culturales. En Raile, M, Marriner, A. Modelos y teorías en Enfermería. 7a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2011. p. 454-479. [ Links ]

7. Boyle, JS. Estilos de etnografía. En: Morse, JM, compilador. Asuntos críticos en los métodos de investigación cualitativa. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia; 2003. p.185-214. [ Links ]

8. Fariñas, G. Acerca del concepto vivencia en el enfoque histórico cultural. Revista Cubana de Psicología. 2005; 16 (3): 62-66. [ Links ]

9. Figueredo, N. Investigación cualitativa en ciencias de la salud. Contribuciones desde la etnografía. Cuidados Humanizados (Internet). 2017 (acceso 17 de junio de 2019); 6(Núm. Especial): 14-19. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v6iEspecial.1445 [ Links ]

10. Knoblauch, H. Etnografía enfocada. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research (en línea). 2005 (acceso 17 de junio de 2019); 6(3). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.20 [ Links ]

11. Hernández, R, Fernández, C, Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación. 5a ed. México: McGraw-Hill; 2010. p. 471-478. [ Links ]

12. Lolas, F, Quezada, A. ¿Qué hace que la investigación clínica sea ética? Siete requisitos éticos. Pautas éticas de investigación en sujetos humanos: nuevas perspectivas. (Internet) 2003 (acceso 18 de diciembre de 2018); 84-95. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.libros.uchile.cl/files/presses/1/monographs/258/submission/proof/files/assets/basic-html/page2.html [ Links ]

13. Ochoa, G, Inalef, R, Valenzuela, A. Percepción de salud - enfermedad de usuarios indígenas urbanos adscritos al sistema público de salud. (Internet). Chile: Ministerio de Salud ; 2012 (acceso 12 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://germina.cl/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/estudio_percepcion_salud_enfermedad.pdf [ Links ]

14. Patiño, A, Sandín, M. Diálogo y respeto: bases para la construcción de un sistema de salud intercultural para las comunidades indígenas de Puerto Nariño, Amazonas, Colombia. Salud colect. (en línea). 2014 (acceso 14 de enero de 2019); 10(3): 379-396. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1851-82652014000300008 [ Links ]

15. Caceres, P, Ribas, A, Gaioli, M, Quattrone, F, Macchi, A. The state of the integrative medicine in Latin America: The long road to include complementary, natural, and traditional practices in formal health systems. Eur J Integr Med (en línea). 2015 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 7(1):5-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2014.06.010 [ Links ]

16. Cardona, Jaiberth, Rivera, Y, Carmona, J. Expresión de la interculturalidad en salud en un pueblo emberá-chamí de Colombia. Rev. cub. salud pública (en línea). 2015 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 41(1):77-93. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662015000100008 [ Links ]

17. Painemilla, A., Sanhueza, A., Venegas, J. Abordaje cualitativo sobre la incorporación del enfoque de salud intercultural en la malla curricular de universidades chilenas relacionadas con zonas indígenas. Rev Chil Salud Publica (en línea). 2013 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 17(3): 237-244. doi:10.5354/0719-5281.2013.28607 [ Links ]

18. Fleckman, J, Dal, M, Ramirez, S, Begalieva, M, Johnson, C. Intercultural competency in public health: a call for action to incorporate training into public health. Front Public Health (en línea). 2015 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 2 (210).doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00210 [ Links ]

19. Vargas, S, Berúmen, L, Arias, I, Mejía, Y, Realivázquez, L, Portillo, R. Determinantes sociales de la atención comunitaria: percepciones de la enfermera e indígenas Rarámuris. CULCyT (en línea). 2015 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 57(12). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://erevistas.uacj.mx/ojs/index.php/culcyt/article/viewFile/857/811 [ Links ]

20. Aizenberg, L. Hacia una aproximación crítica a la salud intercultural. Rev. latinoam. poblac. (en línea). 2011 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 9(5): 49-69. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=323827305003 [ Links ]

21. Hasen, F, Interculturalidad en Salud: Competencias en Prácticas de Salud con Población Indígena. Cien. enferm. (en línea). 2012 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 18(3): 17-24. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-95532012000300003 [ Links ]

22. Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales. Orientaciones para la Implementación del Modelo de Atención Integral de Salud Familiar y Comunitaria (en línea). Chile: Ministerio de Salud ; 2013 (acceso 12 de diciembre de 2018). Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/e7b24eef3e5cb5d1e0400101650128e9.pdf [ Links ]

23. Muñiz, N. Cuidados Enfermeros y Coherencia Cultural. Ene (en línea). 2014 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 8(1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1988-348X2014000100004 [ Links ]

24. Duan, Y. A concept analysis of cultural competence. Int J Nurs Sci (en línea). 2016 (acceso 14 de enero de 2019); 3(3): 268-273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.08.002 [ Links ]

25. Castrillón, E. La enfermera transcultural y el desarrollo de la competencia cultural. Cul Cuid (en línea). 2015 (acceso 14 de julio de 2019); 19(42): 128-136. doi:10.14198/cuid.2015.42.11 [ Links ]

26. Castillo, J. El Cuidado Cultural de Enfermería: Necesidad y Relevancia. Rev haban cienc méd (en línea). 2008 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 7(3). Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1729-519X2008000300003 [ Links ]

27. Romero, MN. Investigación, Cuidados enfermeros y Diversidad cultural. Index Enferm (en línea). 2009 (acceso 4 de diciembre de 2018); 18(2): 100-105. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962009000200007 [ Links ]

28. Henderson, S., Barker, M., Mak, A. Strategies used by nurses, academics and students to overcome intercultural communication challenges. Nurse Educ Pract (en línea). 2016 (acceso 14 de enero de 2019); 16(1): 71-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.08.010 [ Links ]

How to cite: Rivas Riveros E., García Silva V., Catalán M. Y. Mapuche mothers 'lives during the hospitalization of their children, in a high complexity hospital in southern Chile. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2020; 9(1): 33-43. Doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v9i1.2147

Contribution of the authors: a) Study conception and design, b) Data acquisition, c) Data analysis and interpretation, d) Writing of the manuscript, e) Critical review of the manuscript. E.R.R. contributed in a,b,c,d,e; V.G.S. in a,b,c,d,e; Y.C.M. in a,b,c,d,e.

Received: March 09, 2019; Accepted: December 03, 2019

texto em

texto em