Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.9 no.1 Montevideo 2020 Epub 01-Jun-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v9i1.2145

Original Articles

Obstetric violence: manifestations posted on Facebook virtual groups

1 Facultade de Enfermagem e Obstetrícia, Universidad Federal de Pelotas. Brasil. ju_ribeiro1985@hotmail.com

Keywords: violence; violence against women; maternal-child health services; social networking; health personnel

Palavras chave: violência; violência contra a mulher; serviços de saúde materno-infantil; rede social; pessoal de saúde

Palabras clave: violencia; violencia contra la mujer; servicios de salud materno-infantil; red social; personal de salud

Introduction

Obstetric violence refers to violence that occurs at the time of pregnancy, delivery, birth and/or postpartum, including abortion. According to the Ministry of Health (MOH), it can be classified into physical, psychological, verbal, symbolic and/or sexual violence, neglect, discrimination and/or excessive and unnecessary or non-recommended conducts, which are often harmful and not based on scientific evidence 1.

Violent practices submit women to rigid and, in most cases, unnecessary rules and routines, which do not respect their bodies and their natural rhythms and prevent them from exercising their role,1 making the moment of delivery difficult and unpleasant. These practices include lying to the women about their health condition to induce elective cesarean section or not informing them about their health situation and necessary procedures 2.

In Brazil, one in four women suffers violence during delivery. The high rates of interventions employed in delivery and birth care were evidenced in the results of the Nascer no Brasil survey, which aimed to analyze obstetric interventions in women at normal risk 3-4).

The Nascer no Brasil survey, a national hospital-based study of puerperal women and their newborns carried out from February 2011 to October 2012 showed that, in relation to interventions performed during delivery, venous puncture was performed in more than 70% of the women, about 40% received oxytocin and underwent amniotomy (deliberate rupture of the membrane surrounding the fetus) to accelerate delivery, and 30% received spinal/epidural analgesia. Regarding interventions performed during delivery, the lithotomy position (lying face up and knees bent) was used in 92% of cases, the Kristeller maneuver (applying pressure to the upper part of the uterus) was used in 37%, and episiotomy (cut in the perineum region) in 56%. This number of interventions was considered excessive and devoid of scientific support for their justification 3.

Obstetric violence can also be identified in other forms of treatment given to women during the pregnancy-puerperal period, such as: pilgrimage through different services until receiving care; lack of listening and lack of time to give attention to users; coldness, harshness, lack of attention, negligence and mistreatment on the part of professionals, motivated by discrimination of age, sexual orientation, physical disability, gender, racism, mental illness; violation of reproductive rights (discretion of women undergoing abortion, accelerated delivery to free beds, prejudices about sexual roles, and disqualification of practical knowledge and life experience because of scientific knowledge 5.

Although obstetric violence is found to be a violation of women's rights because it involves the loss of autonomy and decision-making power over their own bodies, in Brazil there is no federal law that protects women during pregnancy and delivery. For this reason, the use of social media has been gaining prominence as a place for discussing this topic, as well as other issues considered constraining or taboos by society. This is because in these environments people find spaces for exchanging experiences with others who have been or are going through similar situations, generating content that is available and accessible to a large audience 6.

Currently, there is a large number of blogs, websites and Brazilian groups on social networks about pregnancy and motherhood on the Internet, filled with personal testimonies and various types of information. They work as a repository of birth reports, producing texts in which women expose their experiences (positive and negative) in a personal and emotional way 7.

Specifically Facebook has enabled interaction through comments, participation in groups, organization of a space for meeting and sharing information and discussing ideas 8-9. This resource is often used by humanized delivery adherents as a tool for the empowerment of women, fostering intense debates with a view to fundamental and urgent changes in delivery care in Brazil 7.

In this sense, investigating the manifestations about obstetric violence posted in Facebook groups is relevant in the sense of identifying the gaps and weaknesses existing in the assistance to women during pregnancy and delivery that culminate in obstetric violence. Thus, the questions that guided this study were: What are the manifestations about obstetric violence posted in virtual groups on Facebook? What kind of posts are shared? What do they indicate about the care provided to women during the pregnancy/puerperal period?

The answers to these questions can support the practice of nursing and health professionals, assisting them in proposing a new form of care, considering the social network Facebook as a tool for change in the assistance to women during the pregnancy/puerperal period.

By strengthening virtual networks, we also strengthen women’s participation in politics. Moreover, with the expansion of access to the global network, exchange of information and experiences may be available to a greater number of women, who, being more informed and more aware of their bodies and their health, may demand changes in the health system. Thus, female empowerment promoted by collective actions can help women to demand fundamental and urgent changes in delivery care in Brazil 7.

Given the above, the present study had the general objective of knowing the manifestations about obstetric violence posted in Facebook groups. The specific objectives were:

Method

This is a qualitative, exploratory and descriptive study conducted in public groups hosted on the virtual social network Facebook that addressed the theme of obstetric violence.

Virtual social networks are organizations with certain characteristics, such as the intentionality of the objectives. On the social network Facebook, groups are a joint association between people who share the same interests. Thus, investigating them involves understanding how the participants organize and mobilize themselves to integrate these networks 10).

When posts and experiences shared by users are available to anyone with access to the social network, this group is defined as a public group. Groups whose posts are restricted to followers are defined as private groups 11).

The present study analyzed posts from public groups hosted on the social network Facebook that addressed the theme of obstetric violence, published in the year 2017. The following inclusion criteria were adopted: posts from public groups; national; directed at the theme of obstetric violence. The exclusion criteria were: posts from international groups; groups exclusively of health professionals (according to information in the description of the groups); and groups with no posts in the last 30 days.

Data collection was carried out in September 2018 on the social network Facebook. First, a search was made for public groups that addressed the theme of obstetric violence in the abovementioned virtual social network, through the search window provided by it, which allows users to find people or interest groups.

The collection was carried out in five stages:

1º) The keywords obstetric violence were inserted in the search window, and then the groups option was selected in the Facebook navigation panel.

2) The filter “show only public groups” was applied to the results obtained in the search in order to identify groups with posts available to anyone with access to the social network.

3) The groups found were also evaluated according to nationality, participants, and existence of posts in the last 30 days. Thus, groups were selected to be included in the study.

4) The content of the selected groups was analyzed, covering the following aspects: group name, year of creation, definition, administrator, number of followers, and type of posts. The posts were classified according to the following typology:

a) Quotes (references from renowned authors, excerpts from songs, catch phrases, epigraphs and book passages).

b) Questions

c) News

d) Images and videos

e) Personal stories and experiences

The information captured also included: number of comments, reactions (Likes, Love, Wow, Sad, Haha, Grr) and sharing. Such aspects were inserted and organized in a spreadsheet, thus supporting the synthesis of the data and subsequent characterization of the groups.

5) Data were collected upon reading the posts made in the selected groups, what was done in the period from January to December 2017. Afterwards, the posts were copied and stored in the Atlas ti softwares for subsequent analysis through the Minayo's operative proposal 12).

It should be noted that posts that were not related to the theme of obstetric violence were disregarded.

This study complied with Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council of the Ministry of Health, which addresses research involving human beings. The study was sent and approved by the Research Ethics Committee according to Opinion number 2,845,836 and Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appreciation (CAAE) 95390418.2.0000.5316.

In order to protect the identity of people in the selected posts, the data that allows their identification such as name, place, residence, state, virtual group, among others, were deleted. The anonymity of the participants was guaranteed by the use of codes for identification, such as “P” to indicate “Post” in the group, plus the Arabic number that indicates the order in which the data was collected.

Results

The characterization of the posts shared in the Facebook groups and the gaps in assistance to women during the pregnancy/puerperal period that culminate in obstetric violence will be presented below.

Characterization of posts shared in Facebook groups

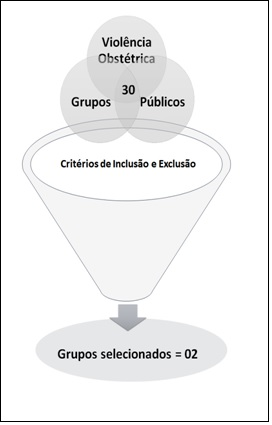

The search on the Facebook navigation panel detected 113 (100%) groups that addressed the theme of obstetric violence, of which 30 (26.54%) were public groups and 53 (46.90%) private.

Among the public groups, 21 (18.58%) international groups were excluded, namely: 11 (9.73%) from Argentina, four (3.54%) from Mexico, two (1.77%) from Colombia, one from Chile (0.88%), one (0.88%) from Venezuela, one (0.88%) from Guatemala, and one (0.88%) from Paraguay. In the national scenario, nine (7.96%) groups were identified, of which seven (6.19%) had no posts in the last 30 days and, therefore, were excluded from the study. No groups were identified with posts made exclusively by professionals.

Thus, two (1.77%) groups hosted on Facebook that addressed the theme of obstetric violence were selected for analysis of posts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow chart of the selection process of public groups hosted on the social network Facebook that address the theme of obstetric violence - Pelotas, RS, September 2018

When analyzing the selected groups, it was found that the 1st Group had a total of 27 posts in 2017 and the 2nd Group had 36, totaling 63 (100%) posts. Nineteen (30.16%) posts were excluded: one (1.59%) for being repeated in the same group and 18 (28.57%) for not meeting the objectives of this study, sometimes reflecting the interest of research with different approach.

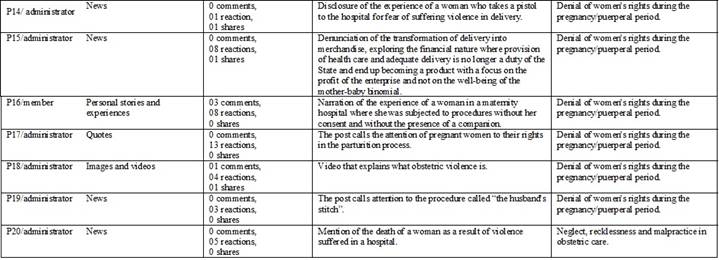

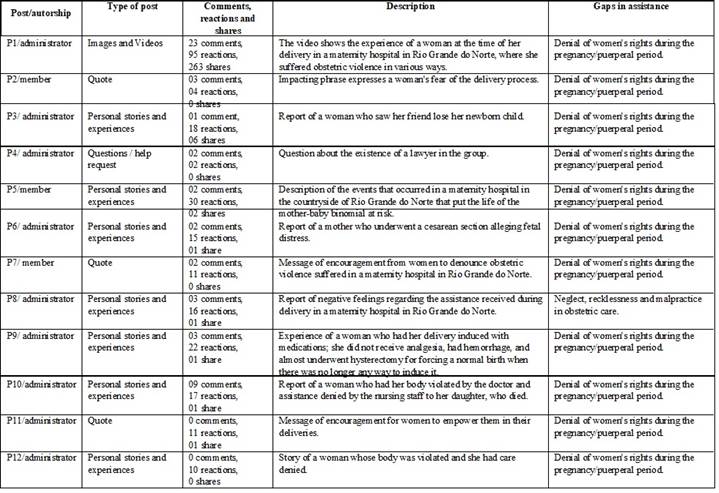

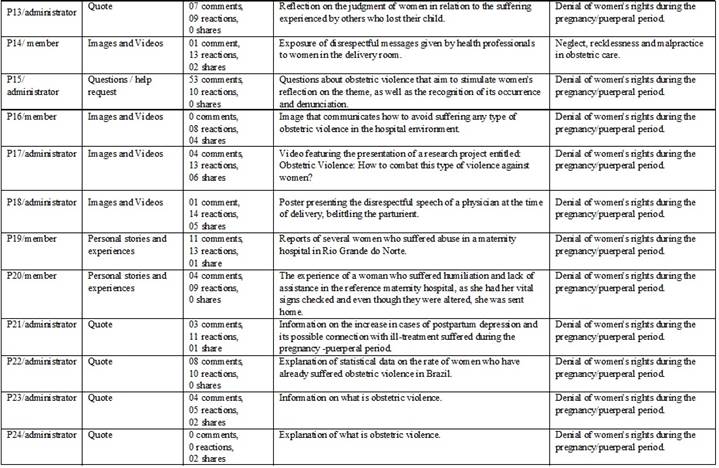

The selected posts (n = 44, 100%) showed diversity in relation to the typology: ten (22.73%) were quotes of catch phrases; two (4.55%) were questions, which indicated the participants’ search for specialists (psychologist and lawyer); 13 (29.54%) were news, which reported situations of obstetric violence in a given service, events related to the theme; eight (18.18%) were images and videos which showed excerpts from course completion papers, comedians mocking the naturalness of scheduling cesarean sections for medical convenience, or still, extolling positive attitudes against obstetric violence; and 11 (25%) were Personal stories and experiences which portrayed situations of obstetric violence experienced by the participants (Box 1, Continued Box 1 and Box 2, Continued Box 2).

It was seen that the posts selected for this study were made, predominantly, by the administrators of the groups. In the 1st Group, of the total of 20 (100%) selected posts, 17 (85%) were made by the administrator and three (15%) by members of the group. In the 2nd Group, of the total of 24 (100%) posts, 17 (70.83%) were made by administrators and seven (29.17%) by group members.

As for comments, reactions and shares, it is considered that such actions were not expressive, since the numbers were low. The 1st Group obtained a maximum of four comments, 13 reactions and only one share. The 2nd Group obtained a maximum of 23 comments, 95 reactions and 263 shares.

Gaps in assistance to women during the pregnancy/puerperal period that culminate in obstetric violence

From the analysis of the posts shared in the Facebook groups, two categories emerged related to the gaps in assistance to women in the pregnancy/puerperal period that culminate in obstetric violence: Denial of rights to women in the pregnancy/puerperal period and Negligence, recklessness and malpractice in obstetric care.

Denial of rights to women during the pregnancy/puerperal period

The posts depict situations experienced by women in the pregnancy/puerperal period when rights are denied, including situations of analgesia during labor, presence of a companion of the woman’s choice during labor and postpartum, realization of procedures without consent or respect for the woman’s preferences, such as the Kristeller Maneuver, episiotomy, and “the husband's stitch”. This gives evidence that assistance to women in the puerperal period ignore their role, putting them as distant from actives participants during a physiological event that it is their own, adding drugs and procedures inadvertently.

Neglect, recklessness and malpractice in obstetric care

The posts point to actions taken by health professionals in obstetric care, which include negligence, malpractice and imprudence. Neglect happens when the professional puts the life of the mother-baby binomial at risk by omitting care or when the pregnant woman released with severe changes in blood pressure from care. Malpractice is made explicit in the professionals’ unpreparedness for the exercise of humanized assistance during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium. Recklessness is revealed when professionals have knowledge about the rights of women during pregnancy and delivery and still perform procedures without the women’s consent or utter disrespectful and pejorative statements to them, or even when the doctors perform cesarean sections for their own convenience even when they know the risks involved.

Discussion

The analysis of the data shows that the majority of groups that address the topic of obstetric violence on Facebook are private, which can be understood as a form of protection and guarantee of cohesion among the interests of its participants. In Brazil, discussions about obstetric violence are still incipient, which is why women are being mobilized through the use of cyberactivism strategies. In these spaces, activists for the humanization of delivery form a single public sphere, more visible and more likely to challenge the dominant discourse 14 of hegemonic medical knowledge, in which violent and aggressive practices are perpetuated as “praxis” and supported according to medical-hospital knowledge/practice 15.

According to the survey, Brazil ranks second in terms of number of public groups related to the theme of obstetric violence, with nine groups, following Argentina, with 11 groups. It is noteworthy that in Argentina, with the advance of democratization, the first public policies with an emphasis on gender equality were introduced, including the guarantee of female representation and participation in the creation, implementation and control of these policies 16.

In Brazil, however, the movement against obstetric violence emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, driven by groups of health professionals, defenders of women’s human and reproductive rights and by a portion of the feminist movement, as a way of promoting the discussion about violence in delivery and the fight against it 15.

The movement against obstetric violence in Brazil emerged from the growing criticism regarding delivery care in the country, which culminated in a “movement in favor of the humanization of delivery and birth”. Such movement is based on the recognition of the active participation of women and their role in the delivery process, with an emphasis on emotional aspects and the recognition of female reproductive rights 15. Currently, it is supported by current public policies.

Regarding the feeding of the groups through posts, it was identified that only two public groups in Brazil remained active, with posts in the last 30 days prior to the collection. In addition, most of the posts were made by their administrators, showing an individual effort to give visibility to the topic, mainly through the dissemination of news (n = 12; 27.27%), stories and personal experiences (n = 11; 25%) that portrayed situations of obstetric violence, as well as publication of citations of catch phrases (n = 10; 22.73%) aiming at the dissemination of women's rights in the pregnancy/puerperal period, empowerment of women, and ensuring of the humanization of delivery and birth.

Researchers point out that discussions on obstetric violence, mobilized by the use of collective cyberactivism strategies, give voice to women who went through situations of violence in the pregnancy/puerperal period, visibility to the theme, space for discussion and, gradually, denaturalization of the occurrence of violence. In this sense, we can highlight the collective posts, copyright texts published in personal spaces on a predetermined date in order to achieve greater attention to the subject; the easy and virtually free sharing of information, which makes it possible to disseminate far-reaching content instantly; and channels for exchanging messages between people or groups, which facilitate the articulation and organization of movements 14).

In this sense, the use of social networks has great potential to set up channels for the rebirth of delivery and the denaturalization of obstetric violence, as their authors are determined to seek more humanized and less violent delivery care, giving greater visibility to the theme by taking it out of obscurity 14. For that, it is necessary that such initiatives constitute a continuum, promoting discussions about the meaning of the expression “obstetric violence”, problematizing it, removing the invisible veil that makes it a silent presence 15).

In view of this scenario, it is imperative that health professionals engage and even lead virtual groups linked to the theme, since no groups with this profile were found. Through this initiative, it is believed that the posts gain greater credibility by other users, because they acquire the stamp of scientific knowledge. Consequently, they can be shared, giving visibility to the theme and becoming an agenda for discussions in the virtual environment, thus allowing the rehearsal and enhancing the expression, manifestation and empowerment of women in relation to their own event, delivery and birth.

The results of the present study show that, even with the policy for humanization of delivery and birth, practices that seek to guarantee the protagonism of women and their rights during the pregnancy/puerperal period still have little recognition in the social sphere, reflecting on a violent care practice. In line with this statement, the survey carried out by the Perseu Abramo Foundation pointed out that one in four women suffers violence during delivery 17.

As a gap in assistance to women during during the pregnancy/puerperal period that culminates in obstetric violence, the posts selected in this study showed the denial of rights such as analgesia during labor; companion of the woman’s choice during labor and postpartum; performance of procedures without consent or respect for the woman’s preference, such as the Kristeller Maneuver, episiotomy and “the husband’s stitch”.

According to the Ministry of Health, all women during labor must have access to methods of analgesia, including non-pharmacological methods (bath, shower, massage, etc.), regional analgesia and other analgesic substances (opioids). In addition, the Kristeller maneuver in the second period of labor is prohibited, as well as the routine episiotomy during spontaneous vaginal delivery 1).

Regarding the presence of a companion during the pregnancy/puerperal period, the Law of Companion (Law number 11,108, of April 7, 2005), determines that SUS health services, from the private or affiliated network, are obliged to respect the right of the pregnant women to a companion throughout the period of labor, delivery and postpartum. The companion is to be indicated by the pregnant woman, and this person may be the baby’s father, the current partner, the mother, a friend, or another person of her choice 18.

However, research indicates the failure to comply with such recommendations and rights. The survey “Born in Brazil: National Survey on Delivery and Birth” found that, in relation to interventions performed during labor, 30% of women received spinal/epidural analgesia; in 37% of deliveries, the Kristeller maneuver (applying pressure to the upper part of the uterus) was performed, and in 56%, episiotomy (cutting in the perineal area) was performed. The number of such interventions was considered excessive and without scientific support in international studies 3.

Another research whose objective was to verify the prevalence of obstetric violence in the maternity ward of a teaching hospital in the countryside of the state of São Paulo, revealed that the most common forms of violence were prohibition of a companion, failures in clarifying doubts, and performance of obstetric procedures without authorization/clarification (episiotomy, artificial amniotomy and enema) 19).

In view of such data, it is emphasized that women in labor must be treated with respect, have access to evidence-based information and be included in decision-making. To this end, the professionals who assist these women must establish a relationship of trust with them, asking them about their wishes and expectations. Health professionals must be aware of the importance of their attitude, the tone of voice and the words used, as well as the way care is provided 1).

The present study also pointed out that another gap in assistance to women in the pregnancy/puerperal period that culminates in obstetric violence involves the actions practiced by health professionals in obstetric care that imply negligence, malpractice and recklessness. In line with this finding, the literature reveals that the Brazilian obstetric model is marked by the need for a quick delivery, without respecting the woman’s autonomy, favoring the occurrence of unnecessary interventions based on practices without scientific evidence to support them, a condition that favors the occurrence obstetric violence 20.

In this regard, the legitimation of hegemonic medical knowledge stands out, in which the professional performs interventions even though their inappropriate use can be harmful to parturients, such as the use of oxytocin in order to accelerate delivery, elective cesarean sections, episiotomy, among others 15. As a result of these actions, some women die, others carry physical and psychological consequences, and many survive but marked by such violence 21.

Researchers explain that the models of obstetric care in force in Brazil disrespect and/or ignore sexual, reproductive and human rights, and this can be seen in the high rates of cesarean sections and in the mistreatment suffered by women in maternity hospitals 22). This scenario reveals the urgency of fighting for better conditions of parturition, free from routinely unnecessary impositions, which jeopardize the woman’s autonomy and place her as being unable to give birth without medical procedures, often offered as a cascade of interventionist practices that interfere in the birth process 23.

It should be noted that all women are entitled to obstetric care free from negligence, malpractice and recklessness. Therefore, it is not enough that the women and babies survive delivery; it is imperative that their care be dignified, respectful, humanized and conducted with evidence-based practices, since this is the minimum that health professionals and services must offer.

Conclusion

The results of the present study point to the existence of few public groups that address the theme of obstetric violence. They reveal that the theme is controversial, and most groups prefer to explore it in the private sphere, in a protected way, safeguarding cohesion between the interests of its participants. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that, in Brazil, users of the social network Facebook have been giving greater visibility to the theme through virtual groups.

However, this is an isolated movement, centered on the efforts of a few people, without actually having engagement and social recognition, which is evident by the fact that the posts were made for the most part by the administrators of the groups. Furthermore, they had reduced dissemination in the virtual environment, as few contents were shared or motivated other users to express reactions.

With regard specifically to the typology of the posts, this was diverse, consisting mainly of the dissemination of news, stories and personal experiences, and publication of quotes of catch phrases. These posts seek to give visibility to the theme in different ways, as well as denaturalize the occurrence of obstetric violence and empower women through the dissemination of information and of their rights during the pregnancy/puerperal period.

As a gap in the assistance to women in the pregnancy/puerperal period that culminates in obstetric violence, the posts selected for this study showed the denial of their rights and the actions taken by health professionals that imply negligence, malpractice and recklessness. These findings show that, despite the policy for humanization of delivery and birth, practices that seek to guarantee the protagonism of women and their rights in the pregnancy/puerperal period have little recognition so far in the social sphere, reflecting in the violent assistance practice.

As a limitation of the present study, it is pointed out the fact that it was carried out with posts from specific virtual groups that addressed the theme of obstetric violence: public and national. Thus, its results do not portray the manifestations of members of private and international groups.

Moré Pauletti J, Portella Ribeiro J, Corrêa Soares M. Obstetric violence: manifestations posted on Facebook virtual groups Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2020;(9): 3-20. Doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v9i1.2145

REFERENCES

1. Ministério da Saúde. Diretrizes nacionais de assistência ao parto normal: versão resumida (Internet). Ministério da Saúde, 2017(acesso em 2019 fev 22): 1-53. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes_nacionais_assistencia_parto_normal.pdf . [ Links ]

2. Zarnaldo, GLP, Uribe, MC, Nadal, AHR, Habigzang, LF. Violência Obstétrica no Brasil: uma revisão narrativa. Revista Psicologia e Sociedade (Internet), 2017 (acesso em 2018 set 18), (29): e155043. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/psoc/v29/1807-0310-psoc-29-e155043.pdf [ Links ]

3. Leal, MC, Pereira, APE, Domingues, RMSM, Filha, MMT, Dias, MAB, Pereira, MN et al. Intervenções obstétricas durante o trabalho de parto em brasileiras de risco habitual. Caderno Saúde Pública (Internet), 2014 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 30 (Sup):17-47. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-311X2014001300005&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

4. Organização das Nações Unidas. Nações Unidas no Brasil. Documentos temáticos sobre os ODS. Igualdade de gênero: Alcançar a igualdade de gênero e empoderar todas as mulheres e meninas (Internet). Nações Unidas no Brasil, 2017(acesso em 2019 out 15): 1-18 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://nacoesunidas.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Documento-Tem%C3%A1tico-ODS-5-Igualdade-de-Genero-editorado_11junho2017.pdf [ Links ]

5. Santos, RCS, Souza, NF. Violência institucional obstétrica no Brasil: revisão sistemática. Estação Científica (Internert), 2015 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 5 (1): 57-68 Disponível em: Disponível em: https://periodicos.unifap.br/index.php/estacao/article/view/1592/rafaelv5n1.pdf [ Links ]

6. Mamun, MA, Ibrahim, HM., Turin, TC. Social media in communicating health information: an analysis of facebook groups related to hypertension. Preventing Chronic Disease (Internet), Atlanta, 2015 (cited 2018 set 18); 29 (12): 1-10. [ Links ]

7. Gonçalves, AO. Da internet às ruas: a marcha do parto em casa (dissertação). Curitiba (PR): Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2014 (acesso em 2018 nov 14). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://acervodigital.ufpr.br/bitstream/handle/1884/43335/R%20-%20D%20-%20ALINE%20DE%20OLIVEIRA%20GONCALVES.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

8. Assunção, ABM, Jorge, TM. As mídias sociais como tecnologias de si. Revista Esferas; 2014; 3 (5): 151-160 [ Links ]

9.Patrício, MR, Gonçalves, V. Facebook: rede social educativa? In: Encontro Internacional TIC e Educação, 1 Lisboa, 2010 (acesso em 2018 set 18). Anais. Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa, Instituto de Educação, 2010. 593-598. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://bibliotecadigital.ipb.pt/handle/10198/3584 [ Links ]

10. Bobsin, D, Hoppen, N. Estruturação de redes sociais virtuais em organizações: um estudo de caso. Revista de Administração (Internet), 2014 (acesso em 2018 nov 14), 49 (2): 339- 352. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rausp/v49n2/10.pdf [ Links ]

11. Paschoal, LC. Papéis sociointeracionais em grupos de redes sociais na internet. Revista Intercâmbio (Internet), 2014 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 29: 19-39. São Paulo: LAEL/PUCSP. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/intercambio/article/viewFile/20958/15430 . [ Links ]

12. Minayo, MCS. O desafio do conhecimento. 10ª ed. São Paulo: HUCITEC, 2012 [ Links ]

14. Luz, LH, Gigo, VV. Violência obstétrica: ativismo nas redes sociais. Cad. Terapia Ocupacional UFSCar, São Carlos, 2015 23 (3): 475-484. [ Links ]

15. Sena, LM, Tesser, CD. Violência obstétrica no Brasil e o ciberativismo de mulheres mães: relato de duas experiências. Interface comunicação Saúde e Educação (Internet), 2017 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 21 (30): 209-220. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1414-32832017000100209&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt . [ Links ]

16. Schwether, ND, Pagliari, GC. Políticas de gênero para a Defesa: os casos de Argentina e Brasil. Revista de Sociologia e Política (Internet), 2018 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 26 (65): 1-14. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsocp/v26n65/0104-4478-rsocp-26-65-0001.pdf . [ Links ]

17. Venturi, G, Godinho, T. Mulheres brasileiras e gênero nos espaços público e privado: uma década de mudanças na opinião pública. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo, Edições SESC SP, 2013, 504. [ Links ]

18. Brasil. Lei Nº 11.108, de 7 de abril de 2005. Lei do Acompanhante (Internet). Brasília, DF, 2005 (acesso em 2018 set 18). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/lei/l11108.htm . [ Links ]

19. Biscegli, TS, Grio, JM, Melles, LC, Ribeiro, SRMI, Gonsaga, RAT. Violência obstétrica: perfil assistencial de uma maternidade escola do interior do estado de São Paulo. Revista CuidArte Enfermagem (Internet), 2015 (acesso em 2018 ago 08), 9(1):18-25. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://fundacaopadrealbino.org.br/facfipa/ner/pdf/Revistacuidarteenfermagem%20v.%209%20n.1%20%20jan.%20jun%202015.pdf . [ Links ]

20. Carvalho, IS, Brito, RS. Formas de violência obstétrica vivenciadas por puérperas que tiveram parto normal. Revista Electrónica trimestral de Enfermaría (Internet), 2017 (acesso em 2018 nov 12), 47(16):71-9 Disponível em: Disponível em: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/eg/v16n47/pt_1695-6141-eg-16-47-00071.pdf . [ Links ]

21. Kongo, CY, Silveira, KM, Niv, DY, Silva, DRA, Buzatto, GBM, Salgado, HO. Violência obstétrica é violência contra a mulher: mulheres em luta pela abolição da violência obstétrica. 1.ed. São Paulo: Parto do Princípio; Espirito Santo: Fórum de Mulheres do Espírito Santo, 2014. [ Links ]

22. Barbosa, LC, Fabbro, MRC, Machado, GPR. Violência obstétrica: revisão integrativa de pesquisas qualitativas. Avances em Enfermería (Internet), 2017 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 35 (2): 109-202. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0121-45002017000200190 . [ Links ]

23. Pontes, MGA, Lima, GMB, Feitosa, I.P, Trigueiro, JVS. Parto nosso de cada dia: um olhar sobre as transformações e perspectivas da assistência. Revista Ciência da Saúde Nova Esperança (Internet), 2014 (acesso em 2018 set 18), 12(1): 69-78. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.facene.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Parto-nosso-de-cada-dia.pdf [ Links ]

Contribution of the authors: a) Planejamento e concepção do trabalho; b) Coleta de dados; c) Análise e interpretação de dados; d) Redação do manuscrito; e) Revisão crítica do manuscrito. J.M.P. contribuiu em a, b, c, d; J.P.R. em a, b,c,d.,e.; M.C.S. em a,e.

Received: July 19, 2019; Accepted: November 20, 2019

texto en

texto en