Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versão impressa ISSN 1688-8375versão On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.8 no.1 Montevideo jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v8i1.1785

Artículos originales

Cultural care practices in the reproductive continuum of Embera Katio women of the Alto Sinú

1Universidad de Córdoba, Colombia. javierbula@correo.unicordoba.edu.co

Keywords: Women; Ethnic Groups; Practices; Cultural Care.

Palabras clave: Mujer Indígena; Grupos Étnicos; Prácticas; Cuidado Cultural.

Palavras-chave: Mulheres Indígenas; Grupos Étnicos; Práticas; Cuidado Cultural.

Introduction

Culture can be understood, from the perspective of Itcharth and Donati, as a set of patterns or models of social behavior present in a specific community or population group 1). Culture includes, among other practices, a series of customs, codes and norms that reflect the social dynamics of a group 2).

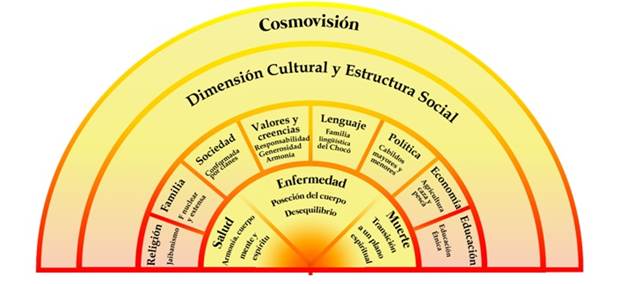

Ramos Lafont indicates that in many indigenous communities there are practices of cultural care, characterized by maintaining a set of ancestral customs that are used to ensure their survival and conservation. These cultural practices are transmitted from generation to generation, especially by women, the main protagonists of the conservation of their legacy 3. Cultural care practices in indigenous women are closely linked to their worldview 4. Understanding the practices of cultural care in the reproductive continuum of Embera women will become a valuable source of information to generate strategies to create an approach to these women during this period.

For nursing professionals, having cultural care competencies is a fundamental task, since they will allow them to negotiate, re-structure or maintain cultural care practices with the communities or special groups with which they interact 5.

In the department of Córdoba in Colombia there are diverse ethnic groups, among them the Embera Katio. In this group women are very vulnerable to health care mispractices because health professionals often do not know how they conceive their reproductive processes; that is why this research is presented as a study question. What are the practices of cultural care in the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú?

Geographically, the department of Córdoba is located in the northwestern part of Colombia, on the extensive Caribbean plain. This department is comprised by 30 municipalities, divided into four subregions: the subregion of the Sinú river basin, the Sabana, the San Jorge river basin and the Costanera zone 6. The indigenous population of the department is located mainly in the municipalities of Tuchín, San Andrés de Sotavento and Tierralta. The municipality of Tierralta is the scenario where this study was conducted. Tierralta is considered the most extensive municipality in the department of Córdoba, consisting of 18 corregimientos, 234 veredas and 4 resettlements of the Embera Katio indigenous group. This municipality is located in the zone of influence of the upper Sinu river basin, which is fed by the tributaries: Verde, Esmeralda and Manso rivers. Historically, these lands have been used for the cultivation of illicit crops and as a corridor for outlaw groups, especially the southern zone and the mountainous area of the territory 7.

The Embera Katio represent 2.7% of the indigenous people in Colombia; the department of Córdoba is the second in the country with the highest concentration of Embera population, housing more than 5,000 people of this ethnic group, that is, 13.4% of the country's Embera population 8. The Katio communities settled in the department of Córdoba are organized by extended families, led by the older man (grandfather), who represents the authority, but after Law 89 of 1890, the Cabildo was established as a way of organizing the political life of their communities 9,10. The Cabildo is a special public entity, whose members are indigenous members, elected and recognized by the community, with a traditional sociopolitical organization; its function is to legally represent the community, exercise authority and perform the activities attributed to it by law.

Methodology

A qualitative ethnographic-interpretative method was carried out for this research; this approach seeks to describe, explain and interpret a phenomenon of study 11,12. This research was materialized with Guber proposals, who affirms that ethnography can be conceived as an approach, as a method and also as a text 13. For this study ethno-nursing was chosen as a method, because the interest of the researchers was to understand the practices of cultural care in the reproductive continuum of the Embera woman 14.

Intentional sampling was used, making reference to the available cases; under this perspective, two types of collaborators were found in coherence with what Leininger described: general cultural collaborators and key collaborators 15. The selection of collaborators was carried out by the researchers, taking into account the principles of relevance, adequacy, convenience, timeliness and availability 16.

Participating collaborators were community leaders, adolescent and adult women of the indigenous community of Tuis-Tuis of the municipality of Tierralta, Córdoba. The general collaborators were an adult leader, a young leader and the community teacher. An initial approach was made to talk about cultural care practices in the reproductive continuum of these indigenous women. These collaborators allowed the immersion to the field and contributed with information that facilitated the approach with the key collaborators.

In order to achieve the saturation of the information, participant observation was carried out four times; each time an ethnographic interview was conducted with each key collaborator and after the analysis it was decided to repeat it, in order to fill the existing gaps. The key collaborators were eight Embera Katio indigenous women of reproductive age, in gestation and postpartum who participated freely in the ethnographic interview.

Regarding the process of collecting information, this occurred at two moments in the course of the research: insertion and field work. Insertion refers to the first observations, field journals and ways to organize the information obtained. It was carried out with the recognition visit and the socialization of the research project. During these visits, meetings were held with the community leaders, who were informed about the project; they shared general information about the indigenous people and the instructions to be followed to obtain the necessary permits. After the insertion phase, they went to the field work where they could attend, observe, record and participate in meetings with the community, with the permission and informed consent of the collaborators.

In order to obtain data, participant observation was used as well as the field diary and the ethnographic interview. The participant observation was performed in two steps, allowing the fluid development of the investigation; the first one was to just observe, without participating, systematically observing what happened in the community without any intervention with the key informants; This type of observation was made in the field insertion, when the reconnaissance visits and the socialization meetings of the project took place.

The second stage corresponds to “involvement versus separation”, a process in which the researchers had contact with the key collaborators and the observation was separated from the involvement that join them 17. All interviews were recorded in audio and supported with field diaries and researchers' records.The ethnographic interview is considered a conversation aimed at understanding the perspectives of the researcher and the researched, in order to capture the points of view of the collaborators regarding the phenomenon being studied 18.

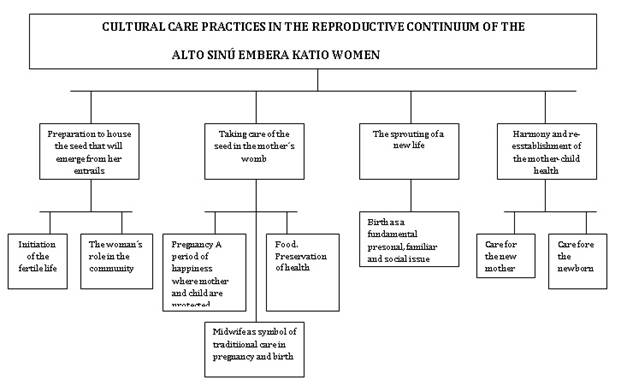

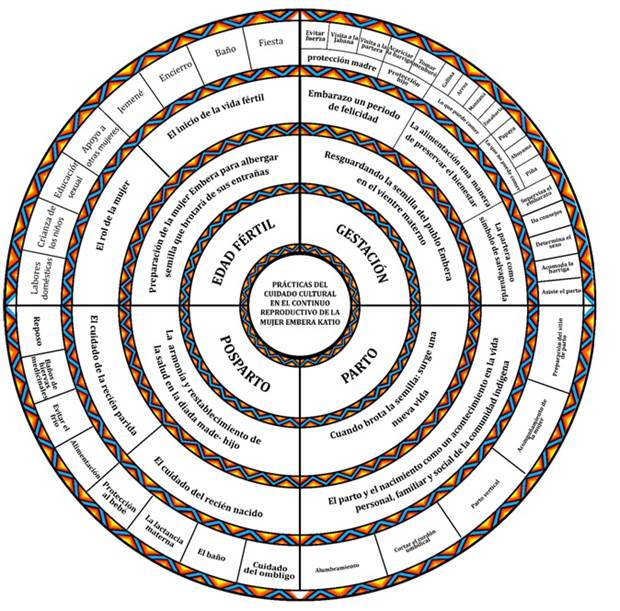

In this study, the data analysis was based on the guide of the Rising Sun facilitator proposed by Leininger from ethno-nursing, as part of the method to provide a rigorous, thorough and systematic analysis of qualitative data 19. This guide served to understand the records of the field journals and the description of the areas that had not been fully explored; it was also a cognitive map that allowed us to understand the main components of the theory, while collecting the data and analyzing the results as shown in Figure 1. 1a. 2

Figure 1: Facilitator of the Rising Sun representing the practices of cultural care in the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katío woman from Alto Sinú

Figure 1a: Facilitator of the Rising Sun representing the practices of cultural care in the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katío woman from Alto Sinú

Regarding the different phases of the research work, there are 4 stages. First, we did the collection, description and documentation of the raw data using the field and computer diary. Second, we identified and categorization of descriptors and coincident according to the model of the rising sun of Leinninger. Third, a contextual analysis of cultural patterns was carried out until saturation was achieved. And finally, the central themes, the synthesis and the interpretation of the data are described.

Results

From the Rising Sun facilitator proposed by Leininger, the analysis of the qualitative data was carried out, following these phases. Once the interviews were transcribed, the researchers carried out an extensive bibliographic review and began the identification of meaningful fragments (descriptors) which were coded using a generic term, related to the stages of the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katio woman, which was translated by a community interpreter, as illustrated in the following example (translation is approximate):

I2 (Yizaketoma) E4P5 "Once you know when you are almost ready to give birth, you look for the midwife; if she says that the baby is head first, one is calm and already knows that one will give birth well ..

Where:

I2: Informant 2 (Yizaketoma, translates to / newly delivered) E4: (Interview 4).

P5: (Paragraph 5).

I2 (Yizaketoma) E4P5 “Ya uno sabe cuándo ya casi va pa parir!, uno busca la partera; si ella dice que está de cabeza, ya uno queda tranquila y ya uno sabe que va parir bien…

Donde:

I2: Informante 2 (Yizaketoma. Traduce a /Recién parida)

E4: (Entrevista 4).

P5: (Párrafo 5).

Once the information was refined, the significant fragments were kept by each key collaborator; finally, through conceptual maps, diagrams and drawings, a comparative analysis was carried out, where codes were assigned when meanings were similar. Then they were grouped, giving rise to patterns when there were common aspects. Next, the patterns were analyzed again looking for similarities and differences, until they were finally grouped into four main themes that describe the cultural care practices in the reproductive continuum of these women.

According to the Theory of Universality and Diversity of Cultural Care, cultural care should be seen as an essential element for human health, well-being and survival 20. In fact, Leininger indicates that care based on culture is essential to help people to deal with healing, recovery, disability and to face death 21.

Next, the interpretative synthesis of each one of the thematic categories that arose from this investigation is presented:

Topic 1. Preparation of the Embera woman to house the seed that will sprout from her insides.

The Embera Katio woman in her own culture is seen as an important person due to her ability to give life and therefore ensure the extension of her ethnicity over time; for this reason, from an early age they are prepared to house the seed that will sprout from their entrails and to assume the responsibility of perpetuating the Embera Katio culture.

A subcategory of analysis that derives from the first topic is the beginning of the fertile life. The beginning of the fertile life of the Embera Katio woman is marked by the Jemené ritual (a term used to refer to the ritual performed at the puberty of women after the first menstruation). Before reaching this stage, the woman is educated to inform the mother about the presence of the first menstrual bleeding and to begin the preparations for the ceremony. This ritual is divided into three moments: the confinement, which has a variable duration and is subject to the end of the menstrual cycle; the bath in the river, that is carried out in order to cleanse the young woman to strengthen her body, and the party, where the community is integrated, asking the protective spirits (jai) to accompany the young woman in her adult life 22.

One moon later, I had a party! ... they painted me with jagua! ... First they locked me in a room where only my mther could come in ..., then they threw me in the river and at the party they gave me drinks! ... I got drunk! ... C1 E1P2 (awera / adolescent)

¡Una luna después, me hicieron una fiesta!… ¡me pintaron con jagua!... ¡Primero me encerraron en un cuarto donde sólo entraba mamá!..., ¡después me tiraron al río y en la fiesta me daban trago!… ¡yo me emborraché!... C1 E1P2 (awera/adolescente)

The second subcategory identified was the Role of Embera Women in the community. The Embera Katio woman has defined functions within her community that include preparing food and beverages, transporting firewood, collecting agricultural products for her home, carrying water and caring for her husband and children. The training process starts from an early age; the parents are in charge of teaching these practices so that in the future they become “good” women, when they decide to start a family. A clear example of this situation is evidenced by the following narration:

Here I am to wash, cook, raise the children and give them advice! ...; to raise them well! ... one goes out to look for firewood, sometimes for banana, and one is in the house! . C4E2P3 (yondrara / adult)

¡Yo aquí estoy pa lavá, cociná, criar los hijos y darles consejos!...; ¡Pa criarlos bien!... ¡uno sale a buscá leña, a veces sale a buscá plátano, y está en la casa!.. C4E2P3 (yondrara/adulta)

Topic 2. Sheltering the seed of the Embera people in the womb.

Pregnancy in this culture is considered a social and family event, framed in happiness by the arrival of a new being. This event means an expansion of the family, culture and community; for this reason, pregnancy is intended to preserve the health and well-being of the mother and the seed that is housed in her womb through activities that protect the health of the mother-child dyad 23.

In this subject three subcategories arise; the first one is Pregnancy: a period of happiness, where the mother and her unborn child are protected. Most women identify their pregnancy by symptoms such as amenorrhea, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and weakness. For them, the identification of signs and symptoms of pregnancy are part of a normal event in their reproductive cycle.Pregnant women recognize the importance of feeling supported by the family, especially by their mother, sisters and sisters-in-law, as can be seen in the following expression:

Sometimes one is taken care of by the mother or inlaws! ... and then one remains at home taking care of one's baby and husband! C3E3P7 (biogo / pregnant)

¡A veces a uno lo cuida la mamá o están las cuñás!… ¡ya despué queda uno en casa cuidando bebé y marido de uno!. C3E3P7 (biogo/embarazada)

It is important to mention that within the cultural beliefs pregnancy is considered as a natural event in the life of the woman, where they follow their beliefs and traditional practices, in addition to the advice given by their family 24.

Pregnant women consider that certain household chores lead to efforts that can be harmful to their health and their unborn child´s, like carrying heavy objects, buckets of water, washing clothes and any other activity that involves sudden movements and changes of balance, because they are activities that cause them "a bad force" as can be confirmed in the next narration.

When one is pregnant one has to do things, but not the heavy ones! ... a bad force can hurt the baby! ... One takes great care when carrying wood, bending down and all that! C2 E4 P6 (biogo / pregnant)

¡Cuando uno está embarazá tiene que hacer los oficios, pero no que sean pesados!… ¡una mala fuerza daña a bebé!..., ¡uno se cuida mucho de cargar leña, agacharse mal y todo eso!… C2 E4 P6 (biogo/ embarazada)

The second subcategory of theme 2 is Food: a way to preserve the wellbeing of the mother and her unborn child. In the search for protection of maternal health, pregnant women consider that the proper diet is a way to protect their own health and their unborn child´s. Food has a particular interpretation and meaning of benefit, protection and safety, which makes pregnant women carry out practices to care for their diet from their own beliefs, personal and family values, seeking to preserve the well-being from both.

I do not eat ahuyama (a kind of pumpkin), it swells the baby´s head and may interfere with the birth! ..., neither papaya nor pineapple, because they have seeds and then the baby is born with pimples! ... C3 E2 P5 (biogo / pregnant)

¡Yo no como ahuyama, eso pone cabezón el bebé y despué atranca el parto!..., ¡tampoco papaya ni piña porque tienen granos y despué bebe sale así!... C3 E2 P5 (biogo/embarazada)

There is also a whole series of rituals with food aimed at ensuring a good delivery; consumption of foods that give strength, drinks that calm the pains of contraction and facilitate dilation and effacement at the moment of birth.

The third subcategory is The midwife as a symbol of safeguarding traditional practices during pregnancy and childbirth. The midwife in the Embera Katio community is recognized as a wise woman, because she has special cultural and symbolic knowledges to provide care to women during pregnancy, delivery assistance, postpartum and newborn care.

She gives advice! ... helps first-timers! ... if you want to know if it's male or female, the midwife knows! ...she squeezes the tit, and if the milk runs in the totuma (a cup made out of a dried pumpkin) then it's a female! ... but if it is concentrated and does not run then it is male! .. She accompanied me with my first child! ..., the others I gave birth just with my mother! … C5 E3 P2 (yondrara / adult)

¡Ella da consejo!..., ¡ayuda a las primerizas!..., ¡si uno quiere sabé si es macho o hembra el bebé, la partera dice!… ¡exprime la teta, si la leche se corre en la totuma es hembra!.., ¡pero si cae concentrá es macho!... ¡Ella me acompañó con mi primer hijo!..., ¡los otros yo los parí solo con mi mamá!... C5 E3 P2 (yondrara/adulta)

In this community, one of the ways to take care of themselves during pregnancy and to guarantee the protection of their unborn child is to visit the midwife, especially for first time pregnant women.

One already knows when is almost ready to give birth! ...one looks for the midwife! ...; if she says the baby is head first then one is calm and knows that she will give birth well! ... C6 E1 P8 (Yizaketoma / freshly birthed)

¡Ya uno sabe cuándo ya casi va pa parir!..., !uno busca la partera!...; ¡si ella dice que está de cabeza, ya uno queda tranquila y ya uno sabe que va parir bien!… C6 E1 P8 (Yizaketoma/recién parida)

The midwives indicate to the women how the pregnancy is going, if the baby is well-adjusted, what sex it is and if everything is well for the birth; they also massage their tummy when they feel pain or when they feel that the baby is in the right or wrong positions. I massage belly so that baby is left head down! … C7 E4 P5 (midwife)

¡Yo sobo barriga para que bebé quede con cabeza pa abajo!... C7 E4 P5 (partera)

By massaging, the midwife pushes the belly from left to right and from back to front, as strong as the pregnant woman can stand it, in order to push the baby down.

Topic 3. When the seed sprouts: a new life emerges.

From this theme comes the following subcategory, Birth as an event in the personal, family and social life of the Embera Katio woman. In a committed way, the family is particularly interested in the physical, emotional and spiritual well-being of the parturient, guiding care actions to provide the woman and her newborn with safe conditions during labor and delivery.

My family always supports me ... a baby is always welcome! ... I have eight children, and the last ones I had them alone in the house! ... C5 E2 P6 (yondrara / adult)

I'm getting ready to give birth! ... I have the clothes ready for the baby to fall into! ... when I'm about to give birth I have to bend down and spread my legs, grabbing a stick and after three pushes the baby comes out! C6 E2 P9 (Yizaketoma / freshly birthed)

I tie the navel with thread, then I clean the blood and cut the navel gut with a new blade! C7 E3 P3 (midwife)

After giving birth, I bathe myself with chivini and parara water! ...; The baby too, so neither I nor the baby get sick! C6 E3 P4 (Yizaketoma / freshly birthed)

¡Mi familia siempre me apoya!..., ¡un hijo siempre es bienvenido!… ¡yo tengo ocho hijos, y los últimos los parí sola en la casa!... C5 E2 P6 (yondrara/adulta)

¡Yo me voy alistando pal parto!... ¡Yo tengo los trapos listos para que bebé caiga!..., ¡cuando voy a parir tengo que agacharme y abrir las piernas agarrando un palo y a las tres jalás sale bebé!... C6 E2 P9 (Yizaketoma/recién parida)

¡Yo amarro con hilo el ombligo, despué separo sangre y se mocha la tripa de ombligo, con cuchilla nueva!... C7 E3 P3 (partera)

¡Despué de parir me baño con agua de chiviní y parará!...; ¡bebé también, eso pa que yo no enferme y bebé tampoco!.... C6 E3 P4 (Yizaketoma/recién parida)

These topics revolve around pregnancy care as a way to prepare for childbirth; with this purpose, it has been observed and documented how women begin to get ready for the birth of their child, from the moment that they learned about their pregnancy status, evidenced by a change in their lifestyle and in the adoption of care practices, entrenched in their personal beliefs and values and influenced by the experiences of other women.

Topic 4. Harmony and restoration of health in the mother-child dyad.

As subcategories of this topic emerged: The care of the newly born. Within the framework of concepts and care practices performed by the recently delivered is the concept of "avoid the cold". This situation leads to a series of practices that allows them to keep the body in balance between cold and heat; this traditional knowledge guarantees them to be well after giving birth.

One gives birth in a closed room, cannot catch cold! ... that hurts! ... uff ... it's a lot of damage! ... One can get cold and the belly hurts after childbirth! ... That's why you take care of yourself so much! C8 E4 P5 (Yizaketoma / newly born)

¡Uno pare encerrao, no puede coger frío!..., ¡eso hace daño!… uff… hace mucho daño! ... ¡A uno puede entrarle frío y la barriga le duele después del parto!..., ¡por eso uno se cuida mucho!... C8 E4 P5 (Yizaketoma/recién parida)

The cold becomes for them an "uncomfortable" feeling, because depending on the place where the cold enters, it begins to produce alterations in the woman's body, with harmful consequences that not only affect the mother, but also the baby.

Food and rest also play an important role in this period; for the Embera Katio culture, the foods of choice in the postpartum are poultry and sugary drinks. They also try to limit their routine activities until they feel better to restart their activities at home.

I ate chicken, chocolate and panela (a sweet food) when I gave birth! ... I ate all that stuff to get my tummy back in place ..., they say that the blood stays in the belly, then the panela helps it to go down and when it is hot, the panela water makes that blood go down faster to avoid troubles and pains! C4 E3 P7 (yondrara / adult)

One should stay still, still, while on a diet! ... You can not wash, you can do nothing during a whole moon, and afterwards you can, but nothing heavy! C8 E4 P6 (Yizaketoma / freshly birthed)

To soften the breast, one draws milk and adds salt! ..., then rub it or pour warm water! C5 E3 P5 (yondrara / adult)

The care of the newborn. In the period after birth, the newborn receives care from his mother in order to protect him and prevent illnesses; this care consists in an exclusive diet of breast milk during the first three months and then the addition of other foods; it also includes navel care with talc and boiled water until it falls, as well as the protection of the newborn with baths of plants and jagua1, among other medicinal plants.

When the baby is born, I bathe him with warm water and soap! ... after a moon, I bathe the baby with the water of matarraton leaves, lemon leaves and chivini leaves so he does not get sick and gets strong! ... C8 E2 P1 (Yizaketoma / freshly birthed)

After that baby is born, I give only breast milk! ..., after three months a pajuil is hunted, the breast is removed, groung and spiced, making a kind of meatball. An elderly person is called to give him his first salty meal! C4E3P7 (yondrara / adult)

¡Yo comía gallina, chocolate y panela cuando paría!... ¡Yo comía todo eso para que se reponiera la barriga!..., ¡dicen que la sangre se queda en la barriga, entonces la panela ayuda a que eso baje y cuando se toma caliente el agua de panela es más rápido que baje esa sangre y así no tener apuros y dolores!... C4 E3 P7 (yondrara/adulta)

¡Uno debe está quietecita, quietecita, mientras que pase dieta!... ¡No puede lavá, no puede hacé na de oficio durante una luna, ya despué sí, pero na pesado!. C8 E4 P6 (Yizaketoma/recién parida)

¡Pá aflojá la teta, uno se saca la leche y le echa sal!..., ¡despué se soba la teta o se echa agua tibia! C5 E3 P5 (yondrara/adulta)

One way to protect the skin of the newborn right after delivery is to oint him with the placenta as a symbol of beauty and protection.

I oint the baby with the placenta, to avoid a rash! ..., I also put a juuajú2 in his hand to protect it from the evil spirits. After a few days some kipará3 are drawn in his body to protect him from evil! C5 E4 P6 (yondrara / adult)

¡Yo unto a bebé la placenta, para evitar salpullido!..., ¡también pongo un juuajú en la manito para protegerlo de los espíritus malos, a los días de nacido se dibujan unos kipará en todo el cuerpo pá protegerlo de la maldad! C5 E4 P6 (yondrara/adulta

Finally, in Figure 3, the cultural care practices identified in the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú are presented, understood as a harmonious process that has a starting point and a completion point that is constantly repeated.

Discussion

Identifying the practices of cultural care in the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú allowed to know different cultural traditions around the reproductive cycle of women, oriented to their care and that of their unborn child. In this research, four themes or categories of analysis emerged with their respective cultural care practices.

There are few records of cultural care practices in the reproductive continuum of Embera Katio women in Alto Sinú, because the theoretical constructs of these cultural practices are only transmitted by oral tradition. The discussion presented below takes as a reference a group of studies of other ethnic groups that document cultural care practices in the reproductive continuum of women.

The Embera Katio provide education to women from an early age so that they assume their proper role within the community. The fertile life of an Embera Katio woman begins with the first menstruation; this event is accompanied by rituals that prepare the woman to provide her with knowledge and strength, indicating to the rest of the community that she is already suitable for the procreation and formation of a family.

Once the new family is established, the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú begins her reproductive cycle, beginning the extension of the family and repopulation of her ethnic group. Pregnancy is considered a period of happiness where the woman protects herself and protects the unborn child; a series of care practices are carried out during pregnancy, which are transmitted ancestrally from one woman to another, from generation to generation and are subject to the customs and beliefs of their culture.

The research carried out by Hernández in 2012 shows that the knowledge and practices of cultural care in pregnant women are according to the information that they have received from their parents, grandmothers and great grandmothers, thus constituting cultural norms that are transmitted from generation to generation 25). In the same way, the study conducted by Ramos Lafont shows that during pregnancy the Zenúes indigenous have a strong root in their traditions and cultural customs, a situation that does not differ from the findings reported in this research3.

The supervision of pregnancy in the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú is mainly provided by the midwife, who accompanies and guides the woman about the care she must have during this stage. The midwife occupies a privileged place in the community, being the figure representing traditional and empirical knowledge of the reproductive processes of women; generally a midwife is asked to provide advice related to pregnancy, delivery and postpartum, to check the position of the baby and if necessary, to accommodate it; the delivery of the first-time birth or difficult births can also be attended by her, as evidenced by the research carried out by Muñoz in the communities of Cauca 26).

Following the approaches described above, Argote and Vásquez argue that motherhood is surrounded by beliefs, myths and taboos that are often represented in the figure of the midwife, who ensures the health and well-being of women during pregnancy, birth and postpartum and motivate both mothers and their families to join the care process 27).

From the Embera Katio worldview, food consumed during pregnancy can determine the existence or not of complications during pregnancy and childbirth, or affect the physical condition of the child. The research carried out by Medina identified that Wounaan pregnant women do not eat some foods to avoid difficulties during childbirth, also assigning physical characteristics to the bone and cephalic structure of the newborn if they have consumed certain foods 28.

In this research it was found that food is very important to preserve the health of the mother and the well-being of her unborn child; in this sense, the Embera Katio woman has a set of nutritional practices related to what they can and can not eat and these are determined by the traditions of their culture; this same situation is evident in some indigenous communities of Peru as reported by the research carried out by Chávez 29).

The customs and beliefs of a culture determine the safety of childbirth and the preparation of the woman for a birth without complications; on the other hand, pregnancy is recognized as a natural process of women linked to diverse customs and beliefs that are transmitted from generation to generation and are conserved through the experience of a social group and a family context, which are intended to preserve the health and well-being of the mother and her unborn child (30, 31).

Another aspect of importance for the Embera Katio culture of Alto Sinú refers to the accompaniment of women during the birth process. The woman who gives birth is the center of attention and family unity. The Embera woman gives birth in her own home, where she has the comfort and warmth necessary to be calm. Labor is carried out with the support of the community midwife when the woman is not experienced; most of the time it is done with the accompaniment of a family member with experience in childbirth care like mothers, grandmothers, sisters, sisters-in-law and in some cases her own husband.

The care of the Embera Katio woman of Alto Sinú in the postpartum is in charge of herself, her mother or the women closest to her; if they are not available, then her husband. The person in charge takes over the tasks previously performed by the woman in her daily life, taking into account that she must refrain from any physical effort or carrying heavy objects as proposed by Ortega in her research: indigenous women after childbirth cannot carry heavy things, cannot eat certain foods, must avoid contacting certain people or visiting certain places 32.

The postpartum period begins with the recovery of the mother and the care of the newborn; in the Embera Katio community of Alto Sinú the recovery of the mother depends mainly on the food consumed, which is based on poultry and sugary drinks.

With regards the care of the newborn, some cultural care practices are highlighted, especially the care of the navel, the protection of the newborn from spirits that may represent a threat to their well-being, the baths with medicinal plants, exclusive breastfeeding for the first three months and the protection of the baby´s body with kipará or jagua to strengthen the character and provide protection to the skin against mosquito bites.

Reflection of the interpretive synthesis of cultural care practices in the reproductive continuum of the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú

Traditional nursing must access the world of Embera Katio women. It must consider their points of view, their knowledge and practices, preserve, maintain, negotiate and restructure patterns of cultural care, in order to provide a safe, beneficial and culturally congruent care oriented to the protection of the mother and her unborn child.

From the perspective of cross-cultural care, the nursing professional must be able to provide a humanized and coherent care consistent with the beliefs, values and practices of the Embera Katio women in the continuum of their reproductive process, reducing cross-cultural conflicts between the disciplinary knowledge of nursing and their own culture.

Conclusions

The reproductive continuum of the Embera Katio woman from Alto Sinú is represented by a set of intergenerational care practices supported by a specific cultural knowledge and behavior, which guarantees the protection of women and their offspring.

Among the practices of cultural care that stand out from this interpretive synthesis are the Jemené, a rite that marks the beginning of the Embera Katio woman to the fertile life; proper feeding: a way to preserve the welfare of the mother and her unborn child; the verticalization of childbirth and the use of medicinal plants during labor; the advice and accompaniment of the traditional midwife during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum; resting and harmony of the mother and the newborn in the postpartum period.

The role of the midwife as caretaker and as a key element to safeguard the beliefs and practices of cultural care in the Embera Katio community of Alto Sinú is very important, due to the experience and knowledge that they have to give advice to women in the continuum of their reproductive cycle.

REFERENCES

1.Itcharth, Laura y Donati, Juan. Prácticas culturales. En: Universidad Nacional Arturo Jauretche: Chile. 2014. p.16. [ Links ]

2.Laza Vásquez, Celmira y Cárdenas, Fernando José. Una mirada al cuidado en la gestación desde la enfermería transcultural. En: Revista Cubana de Enfermería. 2008, vol. 24, no. 3-4, p. 5. (En Línea). (12 de marzo de 2012). Disponible en: Disponible en: www.scielo.sld.enf09308.pdf ) [ Links ]

3.Ramos Lafont, Claudia P. Prácticas culturales de cuidado de gestantes indígenas que viven en el resguardo Sinú. Bogotá, 2011.p. 11. [ Links ]

4.Bula, Javier y Galarza, Keiner. Mortalidad materna en la gestante wayúu de Uribía, departamento de la Guajira, Colombia. Estudio descriptivo año 2016. En: ENFERMERÍA: CUIDADOS HUMANIZADOS. Vol. 6, no. 1, p. 46-53. [ Links ]

5.Ulloa Sabogal. Cuidado cultural en mujeres con embarazo fisiológico: una meta-etnografía. Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Enfermería: Bogotá, Colombia. 2014 [ Links ]

6.Secretaria Departamental de Salud. Departamento de Córdoba. Análisis de La Situación de Salud del Departamento de Córdoba ASIS 2013. [ Links ]

7.Secretaria Departamental de salud. Plan de Desarrollo departamental Córdoba, 2016-2019www.cordoba.gov.co/descargas/Unidos porCordoba.pdf [ Links ]

8.Informe Final Mira Comunidades Indígenas Embera Katio del Alto Sinú. Disponible en: www.humanitarianresponse.info/es/. [ Links ]

9.República de Colombia. Ministerio del Interior. Ley 89 de 1890. Disponible en: www.icbf.gov.co. [ Links ]

10.ComisiónInteramericana de Derechos Humanos. Capitulo XI los derechos de los indígenas en Colombia. En línea: www.cidh.org/countryrep/Colombia93sp/cap.11.htm. [ Links ]

11.Sandoval Casilimas, Carlos. Investigación Cualitativa; Programa de especialización en teoría, métodos y técnicas de investigación social; Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior (ICFES); Bogotá, Colombia. 1996. p 11. [ Links ]

12.Hernández Sampieri, Roberto; Fernández Collado, Carlos; Baptista, Lucio Pilar. Metodología de la investigación, Cuarta edición, Ed. Mc Graw Hill. El proceso de la investigación cualitativa, Tercera parte. 2010. Cap.14, p. 583. [ Links ]

13.Guber, R. (2007). La etnografía. Método, campo y reflexividad. Bogotá: Norma. Hernández, Luz. La gestación: proceso de preparación de la mujer para el nacimiento de su hijo (a). Avances en Enfermería. (Revista en Internet) 2008 (Acceso 12 de Septiembre de 2018) 26(1): 97-102. Disponible en: Disponible en: www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/12889 . [ Links ]

14.Leininger, Madeleine, Teoría de la universalidad y diversidad del cuidado cultural y evolución del método de la etnoenfermería cap. 1; p.1.2006. [ Links ]

15.Sandoval Casilimas, Carlos. Investigación Cualitativa; Programa de especialización en teoría, métodos y técnicas de investigación social ; Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior (ICFES); , Bogotá ,Colombia. 1996. p 11. [ Links ]

16.Guber, R. (2007). La etnografía. Método, campo y reflexividad. Bogotá: Norma. [ Links ]

17.Leininger, Madeleine, Teoría de la universalidad y diversidad del cuidado cultural y evolución del método de la etnoenfermería cap. 1; p.1.2006 [ Links ]

18.Castillo, Edelmira y Vásquez, Martha Lucia. El rigor metodológico en la investigación cualitativa; Colombia Médica, vol.34, no. 3, 2003 [ Links ]

19.Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2011). Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [ Links ]

20.Leininger, Madeleine, Teoría de la universalidad y diversidad del cuidado cultural y evolución del método de la etnoenfermería cap. 1; p.1.2006 [ Links ]

21.Leininger, Madeleine y McFarland, Marilyn. Culture Care Diversity and Universality. A Worldwide Nursing Theory. Chapter, 1. In: Culture Care Diversity and Universality Theory and Evolution of the Ethnonursing Method, Op. cit., p.4. [ Links ]

22.Cosmogonía: El Universo Embera y el Jaibanismo. (En línea) www.pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/caribe/embera/jaibanismo.html. [ Links ]

23.Los Embera Katio: Una Cultura Por Conocer, embera katio.2012. p.2. (En línea): www.losemberakatio.com.co/2012/05/embera-katio.html. [ Links ]

24.Estudio etnosocial Embera-alto Sinú. En: Banco de la República, Centro de Documentación: Barranquilla. 1991. Tomo 2.p.111 [ Links ]

25.Hernández, Luz. La gestación: proceso de preparación de la mujer para el nacimiento de su hijo (a). Avances en Enfermería . (revista en Internet) 2008 (Acceso 12 de septiembre de 2018) 26(1): 97-102. Disponible en: Disponible en: www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/12889 . [ Links ]

26.Muñoz, Sandra, et al. Interculturalidad y percepciones en salud materno-perinatal, Toribio Cauca 2008-2009. Rev. Univ. Ind. Santander. Salud (revista en Internet). 2012 abril (Acceso 19 de junio de 2013); 44 (1): 39-44. Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública. Disponible en: Disponible en: www.revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistasaluduis/article/view/2738 [ Links ]

27.Argote, Luz Ángela, La donación hace la diferencia en el cuidado de padres e hijos, Fam, Saúde Desenv,Curitiba, v4,n1,p.7-15,jan/jun.2002 [ Links ]

28.Medina, Armando y Mayca, Julio. Creencias y costumbres relacionadas con el embarazo, parto y puerperio en comunidades nativas Awajun y Wampis. Rev. Perú. Med. Exp. Salud Pública. Disponible en: www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rins/v23n1/a04v23n1.pdf. [ Links ]

29.Chavez, Rocio, et al. Rescatando el autocuidado de la salud durante el embarazo, el parto y al recién nacido: representaciones sociales de mujeres de una comunidad nativa en Perú. Texto contexto-enferm. (Online).2007, vol. 16, N.4, pp.680-687.ISSN 01040707. www.scielo.br/scielo.php.es [ Links ]

30.García, Clotilde y de la Cruz, Sabina. La salud perinatal de la mujer en una comunidad indígena. En: CIENCIA ERGO SUM. México, 2008. Vol.15, No. 2. p.151 [ Links ]

31.Medina, Armando y Mayca, Julio. Creencias y costumbres relacionadas con el embarazo, parto y puerperio en comunidades nativas Awajun y Wampis. Rev. Perú. Med. Exp. Salud Pública . Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rins/v23n1/a04v23n1.pdf. [ Links ]

32.Ortega J. Géneros y generaciones: conducta reproductiva de los Mayas de Yucatán, México. Salud Colectiva (revista en Internet) 2006 (Acceso 10 de septiembre de 2018) 2(1): 75-89, 2006. Disponible en: Disponible en: www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php . [ Links ]

1 Fruto sagrado del cual se extrae su tintura para curar enfermedades y embellecer el cuerpo mediante tatuajes.

2Hace referencia a una especie de amuleto utilizada por la etnia Embera para la protección de los recién nacidos.

Received: October 12, 2018; Accepted: March 05, 2019

texto em

texto em