Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Odontoestomatología

versión impresa ISSN 0797-0374versión On-line ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.23 no.38 Montevideo 2021 Epub 01-Dic-2021

https://doi.org/10.22592/ode2021n37e212

Research

Dental attendance of female cannabis and/or cocaine users versus non-users. A retrospective four-year cohort study in Argentina

1Departamento de Docencia e Investigación. Establecimiento Asistencial Dr. Lucio Molas, La Pampa, Argentina. marvillarreal@cpenet.com.ar

2Cátedra de estadística. Facultad de Agronomía. Universidad Nacional de La Pampa, La Pampa, Argentina

3Servicio de Laboratorio químico. Establecimiento Asistencial Dr. Lucio Molas, La Pampa, Argentina

Introduction:

Cannabis and cocaine use is a global problem that affects oral health. Most of the research has been conducted on men in rehabilitation programs.

Objective:

to describe and compare the dental attendance and oral diagnoses of women who are cannabis and/or cocaine users and not users for four years.

Methods:

a retrospective cohort study. We compared two groups of women who use and do not use cannabis and/or cocaine, selected in the postpartum period in a public hospital.

Results:

The average age in both groups was 22, and there were no education-related differences. The consumers (n=29) were mostly multiple drug users who sought emergency dental care more often (p=0.0002) and had more gingivitis and periodontitis (p=0.0001) than non-users (n=58).

Conclusions:

women who used cannabis and/or cocaine sought emergency dental care more often and had a more frequent diagnosis of gingivitis and periodontitis than non-users.

Keywords: oral health; cannabis; cocaine; attendance; periodontal disease

Introducción:

El consumo de cannabis y de cocaína constituye un problema global que afecta la salud bucal. La mayoría de las investigaciones se han realizado en hombres, en programas de rehabilitación.

Objetivo:

describir y comparar consultas y diagnósticos odontológicos de mujeres consumidoras y no consumidoras de cocaína y/o cannabis, por un período de 4 años.

Métodos:

estudio de cohorte retrospectivo. Grupos comparados de mujeres consumidoras y no consumidoras de cannabis y/o cocaína, seleccionadas en el posparto en un hospital público.

Resultados:

la edad promedio en ambos grupos fue de 22 años, sin diferencias en nivel educativo. Las mujeres del grupo de consumidoras (n=29) fueron mayormente policonsumidoras, realizaron más consultas odontológicas de emergencias (p=0,0002), y presentaron más gingivitis y periodontitis (p=0,0001) que las no consumidoras (n=58).

Conclusiones:

las mujeres consumidoras de cannabis y/o cocaína realizaron más consultas por emergencias, y presentaron con mayor frecuencia diagnóstico de gingivitis y periodontitis que las no consumidoras.

Palabras clave: salud bucal; cannabis; cocaína; consultas; enfermedad periodontal

Introdução:

O uso de cannabis e cocaína é um problema global que afeta a saúde bucal. A maior parte da pesquisa foi feita em homens, em programas de reabilitação.

Objetivo:

descrever e comparar consultas e diagnósticos odontológicos de mulheres que consumiram e não consumiram cocaína e/ou maconha, durante 4 anos.

Métodos:

estudo de coorte retrospectivo. Grupos comparados de mulheres que usam e não usam cannabis e/ou cocaína, selecionados no período pós-parto em um hospital público.

Resultados:

a média de idade em ambos os grupos foi de 22 anos, sem diferenças de escolaridade. As mulheres do grupo das consumidoras (n= 29) eram, em sua maioria, policonsumidoras, realizavam mais consultas odontológicas de urgência (p= 0,0002) e apresentavam mais gengivite e periodontite (p= 0,0001) do que as não usuárias (n= 58).

Conclusões:

mulheres usuárias de cannabis e/ou cocaína realizaram mais consultas de urgência e tiveram diagnóstico de gengivite e periodontite mais frequentes do que as não usuárias.

Palavras-chave: saúde bucal; cannabis; cocaína; consultas; doença periodontal

Introduction

Cannabis and cocaine use is a global problem with a range of adverse consequences for individual, family, and community health.1 After alcohol and tobacco, cannabis and cocaine are among the most commonly used psychoactive drugs (PD) by adolescents and adults in most countries.1-3

Argentina is no exception. A 2017 study showed that cannabis and cocaine are the most commonly used PD by the general population after tobacco and alcohol. Their use has increased exponentially over the last decade in both sexes. Young people aged between 18 and 24 have the highest use and increase rates.3

In general terms, the consequences of PD on the oral health of users vary considerably. They can affect hard and soft oral tissues, induce malignancy, and predispose patients to infection.4 Periodontal disease, tooth decay, and tooth loss are the most frequently described disorders usually related to more extended periods of consumption time.4-6 The coexistence of a highly cariogenic diet and/or complex individual, family, and social risk factors affects the genesis of poor oral health.2 These factors-which include frequent multiple substance use-hamper diagnosis, therapeutic approaches, and research in affected patients.4,7

A link between cannabis use and periodontal disease has been proven.8-11) The association between cannabis smoking and other disorders, such as caries, soft tissue lesions, and oral cancer, is inconsistent.9) Some authors say that the mental state of cannabis smokers can delay dental treatment visits.9

Regarding cocaine, the frequency of periodontitis, visible plaque, gingival bleeding, and oral mucosal lesions was significantly higher in cocaine users than in non-users.5,12) Tartar and a greater probing depth were the most frequent findings in other studies.6,13

The vast majority of studies on oral health in PD users address men-who are generally in treatment units or rehabilitation programs-and/or lack a comparison group.4,6,12-14

This study aims to describe and analyze the types of dental visits and diagnoses of female cannabis and/or cocaine users over four years and compare them with female non-users.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted. The women were selected from the joint hospitalization sector of the Neonatology Service of Establecimiento Asistencial Dr. Lucio Molas (EALM) of Santa Rosa, La Pampa Argentina. They were selected in the immediate postpartum period.

Female cocaine and/or cannabis users (FU): all the women who fulfilled the screening criteria and had a positive postpartum urine sample for cocaine and/or cannabis. The tests were conducted in the Neonatology Service of the EALM, between 2009 and 2013.

Females not using cocaine or cannabis (FNU): women not complying with the screening criteria and who had delivered in the same neonatal unit on the same day or week as FU. This comparison group was selected based on similar maternal age, place of origin, and social security status as the FU group. Two non-users were chosen for each user to increase the power of the study.

PD detection criteria and method in urine

The test was requested within predefined criteria for immediate postpartum (current reporting or history of drug use, altered mental status, no prenatal care, unexplained central nervous system complications, or newborn symptoms consistent with withdrawal). Each woman signed a consent form and collected her urine in a collection cup. Urine was analyzed by rapid dipstick test for the simultaneous qualitative detection of drugs or metabolites: amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, tetrahydrocannabinol, cocaine, methadone, methamphetamines, opiates, and phencyclidine. The ABON Panel one-step multidrug test performed is a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay.

Cohort recruitment and follow-up process

Women with a positive urine test for cocaine and/or cannabis and two checkups were entered into a research database from 2009 to 2013. No postpartum dental evaluation was performed. The follow-up of the women’s dental visits in the four years was retrospective: we reviewed the digital dental records of the Public Health Information System of the province of La Pampa (SIS). The dental visits of women who joined the study in 2009 were reviewed until 2013, those of 2010 until 2014, and the same was done for those who joined in the following years.

Variables analyzed

Educational level, previous and acquired diseases, type of drugs detected in urine, first-drug use, period of consumption, tobacco and alcohol consumption, type of dental visits (checkup=with an appointment, or emergency=without an appointment), number of visits per woman, dental diagnoses according to the ICD-10, hospitalizations for oral conditions.

Sources

Our research records and Public Health Information System of La Pampa (SIS): this database records demographic data and the medical records of patients attending all public health centers in the province, in the different medical specialties, and in dentistry. Diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).

There were no data gaps in the variables presented.

Data processing and statistics

Office 4.0 Excel was used for data uploading, initial processing, and graphics. InfoStat 2019, University of Cordoba, was used for the statistical analysis.15

Descriptive statistics were used: absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables. Chi-square test (qualitative variables) or Student's t test (quantitative variables) were used to compare the data. A p<0.05 value was considered a statistically significant difference. Rates are expressed as relative risk (RR) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

The study was approved by the EALM Research Ethics Committee (registration number 03/2016). Confidentiality was maintained by coding and limiting the researchers' search, recording, analysis, and access to the study database.

Results

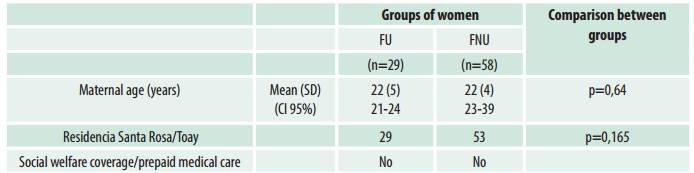

There were no significant differences between female users (FU) and female non-users (FNU) in the selection variables; the groups were homogeneous (Table 1). The average age of both FU and FNU was 22 (FU SD: 4.78; FNU SD:4.33).

Table 1: Comparison of FU and FNU according to selection variables. Women seen postpartum at the Neonatology Service of Establecimiento Asistencial Dr. Lucio Molas, La Pampa, between 2009 and 2013

FU: women who used cocaine and/or cannabis during pregnancy. FNU: women who did not use these drugs during pregnancy. SD: standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

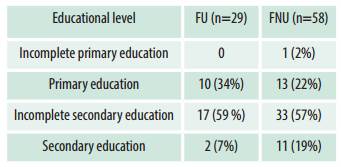

No significant differences were found in educational level (p=0.32). Incomplete secondary education was the most frequent value (Table 2).

Table 2: FU and FNU’s educational level. Women seen postpartum at the Neonatology Service of Establecimiento Asistencial Dr. Lucio Molas, La Pampa, between 2009 and 2013

FU: women who used cocaine and/or cannabis during pregnancy. FNU: women who did not use these drugs during pregnancy

No participant had diabetes, HIV, or an immunosuppressive disorder before pregnancy, acquired during pregnancy, or four years postpartum.

The drugs detected in FU urine were: cocaine (9 women: 31%), cannabis (10 women: 35%), cocaine and cannabis (5 women: 17%), cocaine with phencyclidine and/or benzodiazepines (5 women: 17%).

The age range of first-drug use for cocaine and/or cannabis was 11 to 29 years. The average period of consumption was 5.14 years (SD: 2.96). Ninety-three percent were multiple substance users during pregnancy, mainly using cocaine and/or cannabis with tobacco and/or alcohol. Ninety-three percent of these women reported moking during pregnancy, as did 21% of FNU (p<0.0001). Fifty-five percent of the FU had drunk alcohol during pregnancy, while none of the FNU had done so (p<0.0001).

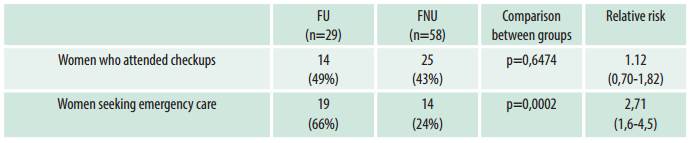

Table 3 shows the type and frequency of dental visits in both groups in four years. There were no differences between groups in the percentage of women who attended checkups, but there was a significant difference in dental emergency visits, where FU surpassed FNU.

Table 3: Dental visits in four years. Comparison of FU and FNU participating in the study between 2009 and 2013. Public Health System. La Pampa, Argentina

Figure 1 shows the percentage distribution of dental emergency visits according to the number of visits (0 to 4) and whether the patients were FU or FNU. Thirty-four percent of FU and 76% of FNU attended no emergency dental visits in four years. Patients attended up to three or four visits in the FU group, which was not the case among FNU.

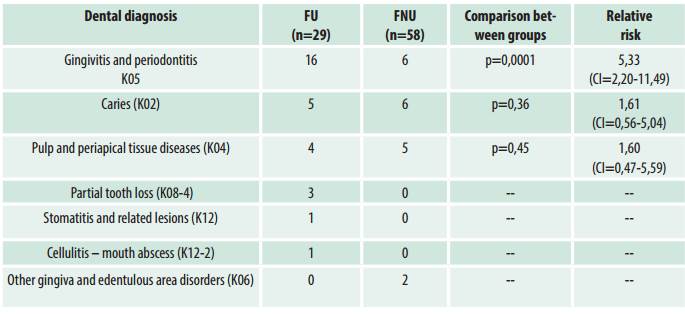

Table 4 shows the comparison of dental diagnoses. FU presented a significantly higher frequency of gingivitis and periodontitis than FNU (p=0.0001).

Ten FU (62%) diagnosed with gingivitis and periodontitis had used these substances for less than seven years. The others had used cannabis and/or cocaine between 7 and 13 years.

Table 4: Dental diagnosis in emergency visits in four years. Comparison of FU (n=29) and FMU (n=58). Public Health System of La Pampa, Argentina.

A FU sought emergency dental care and was admitted for facial cellulitis at the onset of a dental infection. No FU were hospitalized for oral conditions.

Discussion

The women in both groups were public health users, lived close to the hospital where they gave birth, did not have social security or prepaid health insurance, and had a similar education level. This is important since various studies in the general population and PD users found worse oral conditions and greater severity of periodontal disease when the patients had a lower socioeconomic and educational level.16-19

Table 3 shows that we found no significant differences between groups in the percentage of checkup dental visits. Differences were found in emergency visits, which were higher among FU. In addition, FU attended more emergency visits than checkup visits (the opposite of FNU). Some authors have highlighted that cocaine and cannabis users have poor adherence to health checkups.7,20,21 This has also been described in studies on dental visits attended by PD users: they tend to seek care almost exclusively in emergencies.2,22

The main emergency diagnosis in FU was gingivitis and periodontitis, significantly higher than in FNU. Periodontal disease is the main dental consequence of cannabis and cocaine use, although it generally entails periods of consumption longer than 7 or 13 years, longer than described in this study.5,8-12,23 However, the vast majority of FU were also smokers, and half had consumed alcohol.

Multiple substance use characterizes most studies on cannabis and cocaine, with cannabis and tobacco being the most frequent association.10,24 Multiple substance use associated with other coexisting severe social and family factors makes it difficult to determine the weight of each element, or of all of them, on the results presented.7

One limitation of the study is its retrospective nature, which prevents us from knowing the time of smoking and how much alcohol was consumed. Another limitation is that it refers exclusively to the women included in the study in the postpartum period. Therefore, their oral health may have been influenced by pregnancy-related hormonal changes, which many authors associate with poorer periodontal health.25,26

However, this study could be helpful in public health and for professionals as there is scarce information on the oral health of female cannabis and/or cocaine users, especially considering that global consumption continues increasing. FU may be expected to require more dental care in the coming years. In fact, in 2012, a study detected that 21% of those interviewed in the dentist’s waiting room reported problematic use of some type of PD-cannabis in 16.8% of cases and cocaine in 1% of cases-exceeding the general population percentages.27

Another important consideration for professional practice is the potential risk of serious interaction between some local anesthetics and cannabis. Therefore, it would be essential to include questions about PD use in the patient's records.28

Finally, the number of individuals affected by periodontitis has increased substantially in the world and in Latin America in particular.29 Recently, periodontitis has been associated with complications such as death, ICU admission, and the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 patients.30 Health managers, practitioners, and researchers must remain on the lookout for further evidence on the relationship between these increasing data and the effects of cannabis, cocaine, and multiple substance use.

Conclusions

Women who used cannabis and/or cocaine sought emergency dental care more often and had a more frequent diagnosis of gingivitis and periodontitis than non-users. Given the high percentage of multiple substance use, these differences cannot be attributed to one drug or the other. However, this study prompts public health to consider the need to address the oral health of FU in advance and to address the overall complexity of the multiple coexisting risk factors. The immediate postpartum period could be an excellent time to perform a dental checkup and provide prevention guidelines, considering these patients seek care mainly for dental emergencies.

REFERENCES

1. Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):55-70. [ Links ]

2. Teoh L, Moses G, McCullough MJ. Oral manifestations of illicit drug use. Aust Dent J. 2019;64(3):213-222. [ Links ]

3. Secretaria de políticas Integrales sobre Drogas de la Nación Argentina (SEDRONAR). Estudio nacional en población de 12 a 65 años sobre consumo de sustancias psicoactivas. Argentina, 2017. Fecha de acceso: 12 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sedronar/investigacion-y-estadisticas [ Links ]

4. Gigena Pablo C, Bella Marcela I, Cornejo Lila S. Salud bucal y hábitos de consumo de sustancias psicoactivas en adolescentes y jóvenes drogodependientes en recuperación. Odontoestomatología , Internet, 2012; 14( 20 ): 49-59. Fecha de acceso: 17 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1688-93392012000200006&lng=es. [ Links ]

5. Antoniazzi RP, Zanatta FB, Rösing CK, Feldens CA. Association Among Periodontitis and the Use of Crack Cocaine and Other Illicit Drugs. J Periodontol. 2016;87(12):1396-1405. [ Links ]

6. Cury PR, Oliveira MG, Dos Santos JN. Periodontal status in crack and cocaine addicted men: a cross-sectional study. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017 Feb;24(4):3423-3429. [ Links ]

7. Villarreal, M, Belmonte, V, Olivares, JL, Abdala, A . Trayectorias sanitarias de mujeres consumidoras de cocaína y/o cannabis durante el embarazo. Estudio de cohorte retrospectivo en La Pampa, Argentina. Revista De La Facultad De Ciencias Médicas De Córdoba 2020; 77(2), 79-85. Fecha de acceso: 7 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/med/article/view/26838 [ Links ]

8. Thomson WM, Poulton R, Broadbent JM, et al. Cannabis smoking and periodontal disease among young adults. JAMA. 2008;299(5):525-531. [ Links ]

9. Keboa MT, Enriquez N, Martel M, Nicolau B, Macdonald ME. Oral Health Implications of Cannabis Smoking: A Rapid Evidence Review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2020 Jan;86:k2. [ Links ]

10. Mederos M, Francia A, Chisini LA, Grazioli G, Andrade E. Influencia del consumo de cannabis en la enfermedad periodontal. Odontoestomatología 2018; 20(31). Fecha de acceso: 7 de abril de 2021 [ Links ]

11. Chisini LA, Cademartori MG, Francia A, Mederos M, Grazioli G, Conde MCM, Correa MB. Is the use of Cannabis associated with periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res. 2019 Aug;54(4):311-317. [ Links ]

12. Chaparro-González NT, Fox-Delgado MA, Pineda- Chaparro RT, Perozo-Ferrer BI, Díaz-Amell AR, Torres V. Oral and maxillofacial manifestations in patients with drug addiction. Odontoestomatología 2018; 20(32):24-31. Fecha de acceso: 7 de abril de 2021 [ Links ]

13. Fernández-Martínez, N, Denis-Rodríguez, PB, Capetillo-Hernández, G. (2017) Periodontopatias y lesiones orales en consumidores de cocaína con ingreso reciente a un programa de rehabilitación en relación con pacientes no consumidores. Rev Mex Med Forense 2017, 2(1):19-26 . Fecha de acceso: 15 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/forense/mmf-2017/mmf171c.pdf [ Links ]

14. Cury PR, Araujo NS, das Graças Alonso Oliveira M, Dos Santos JN. Association between oral mucosal lesions and crack and cocaine addiction in men: a cross-sectional study. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018 Jul;25(20):19801-19807. [ Links ]

15. Di Rienzo J.A., Casanoves F., Balzarini M.G., Gonzalez L., Tablada M., Robledo C.W. InfoStat versión 2019. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. Fecha de acceso: 12 de junio de 2021. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.infostat.com.ar [ Links ]

16. Hakeberg, M., Wide Boman, U. Self-reported oral and general health in relation to socioeconomic position. BMC Public Health 18, 63 (2018). Fecha de acceso: 21 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4609-9#citeas [ Links ]

17. Paksoy T, Ustaoglu G, Peker K. Association of socio-demographic, behavioral, and comorbidity-related factors with severity of periodontitis in Turkish patients. Aging Male. 2020;1:1-10. [ Links ]

18. Borrell LN, Beck JD, Heiss G. Socioeconomic disadvantage and periodontal disease: the Dental Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):332-339. Fecha de acceso: 22 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470476/ [ Links ]

19. Baskaradoss JK, Geevarghese A. Utilization of dental services among low and middle income pregnant, post-partum and six-month post-partum women. BMC Oral Health. 2020 Apr 20;20(1):120. Fecha de acceso: 10 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-020-01076-9 [ Links ]

20. Magri R, Míguez H, Parodi V, et al. Consumo de alcohol y otras drogas en embarazadas. Arch. Pediatr. Urug. 2007;78( 2 ):122-132. Fecha de acceso: 22 de junio de 2021 [ Links ]

21. Versteeg PA, Slot DE, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. Effect of cannabis usage on the oral environment: a review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6 (4): 315-20. [ Links ]

22. Ramo DE, Delucchi KL, Hall SM, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Marijuana and tobacco co-use in young adults: patterns and thoughts about use. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:301-310. Fecha de acceso: 7 de abril de 2021. Disponible en https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3568169/ [ Links ]

23. Yazdanian M, Armoon B, Noroozi A, Mohammadi R, Bayat AH, Ahounbar E, Higgs P, Nasab HS, Bayani A, Hemmat M. Dental caries and periodontal disease among people who use drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2020 Feb 10;20(1):44. Fecha de acceso: 10 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32041585/ [ Links ]

24. Hartnett E, Haber J, Krainovich-Miller B, Bella A, Vasilyeva A, Lange Kessler J. Oral Health in Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016 Jul-Aug;45(4):565-73. [ Links ]

25. Güncü GN, Tözüm TF, Çaglayan F. Effects of endogenous sex hormones on the periodontium - review of literature. Aust Dent J. 2005;50(3):138-145. [ Links ]

26. Brondani MA, Alan R, Donnelly L. Stigma of addiction and mental illness in healthcare: The case of patients' experiences in dental settings. PLoS One. 2017 May 22;12(5):e0177388. . Fecha de acceso: 18 de abril de 2021. Disponible en: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0177388 [ Links ]

27. Ilgen M, Edwards P, Kleinberg F, Bohnert AS, Barry K, Blow FC. The prevalence of substance use among patients at a dental school clinic in Michigan. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012 Aug;143(8):890-6. [ Links ]

28. Schatman ME, Patterson E, Shapiro H. Patient Interviewing Strategies to Recognize Substance Use, Misuse, and Abuse in the Dental Setting. Dent Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;64(3):503-512. [ Links ]

29. Fischer RG, Lira Junior R, Retamal-Valdes B, Figueiredo LC, Malheiros Z, Stewart B, Feres M. Periodontal disease and its impact on general health in Latin America. Section V: Treatment of periodontitis. Braz Oral Res. 2020 Apr 9;34(supp1 1):e026. Fecha de acceso: 20 de abril de 2021. Disponible en Disponible en https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1806-3242020000200604 [ Links ]

30. Marouf N, Cai W, Said KN, Daas H, Diab H, Chinta VR, Hssain AA, Nicolau B, Sanz M, Tamimi F. Association between periodontitis and severity of COVID-19 infection: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48:483-491. [ Links ]

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest with other authors, institutions, laboratories, professionals, or of other kinds.

Authorship contribution 1. Conception and design of study 2. Acquisition of data 3. Data analysis 4. Discussion of results 5. Drafting of the manuscript 6. Approval of the final version of the manuscript MV, VB, JLO and CL contributed in a, b, c, d, e, and f. MPA contributed in c, d, e, and f.

Received: May 27, 2021; Accepted: July 13, 2021

texto en

texto en