Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Odontoestomatología

Print version ISSN 0797-0374On-line version ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.23 no.38 Montevideo 2021 Epub Sep 30, 2021

https://doi.org/10.22592/ode2021n37e210

Research

Type 1 diabetes mellitus and oral health in Uruguayan children

1Cátedra de Odontopediatría. Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

2Consultor Estadístico, Uruguay

3Unidad de Diabetes. Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell, Uruguay

4Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disorder that affects oral health; there are no data in Uruguay.

Objective:

To determine if the oral health of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus is significantly different from that of children without diabetes.

Method:

Case-control, observational and analytical study. Eighty-six children were evaluated in two groups: 1) type 1 diabetic patients treated at Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell (CHPR) with no associated systemic disease or orthodontic treatment; 2) control group including non-diabetic children attending public school who do not take any medication, are not undergoing orthodontic treatment, and have public health coverage. Variables: biofilm, tooth decay, gingival inflammation, sex, age.

Results

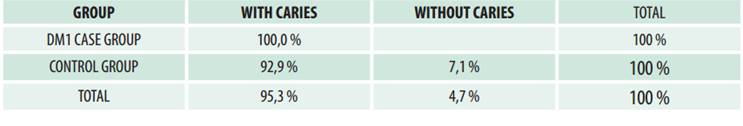

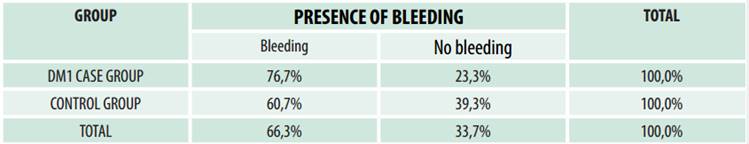

: Biofilm present in 100% of cases in groups 1 and 2. Caries: 100% of Group 1 (DM1) participants and 92.9% of Group 2 (control group) participants have a carious lesion (not a significant difference). Gingival inflammation: 76.7% of DM1 participants and 60.7% of control participants present bleeding on probing (significant difference).

Conclusions

: This study confirms international data highlighting the connection between type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus; oral health; prevalence; epidemiological index

La Diabetes Mellitus es una enfermedad crónica con repercusiones bucales; no existen datos en Uruguay.

Objetivo:

Determinar si el estado de salud bucal de los niños con Diabetes Mellitus tipo 1 es significativamente diferente a los niños sin diabetes.

Método:

Estudio caso-control, observacional y analítico. Se evaluaron 86 niños en dos grupos: DM1) diabéticos tipo 1, asisten al Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell, sin otra enfermedad sistémica asociada ni tratamiento ortodóncico; Control) no diabéticos, concurren a escuela pública, no toman medicación, no cuentan con ortodoncia y se asisten en servicios públicos. Variables: biofilm; caries dental; inflamación gingival; sexo; edad.

Resultados

: Biofilm: presente en 100% de DM1 y Control. Caries: DM1) 100% presenta alguna lesión cariosa y 92,9% en control (diferencia no significativa). Inflamación gingival: DM1) 76,7% sangrado al sondaje y 60.7% en Control (diferencia significativa).

Conclusiones

: Confirma datos internacionales sobre la relación significativa entre Diabetes Mellitus tipo 1 y enfermedad periodontal.

Palabras clave: Diabetes Mellitus; Salud oral; Prevalencia; Índice epidemiológico

Diabetes Mellitus é uma doença crônica com repercussões bucais; não há dados no Uruguai.

Objetivo:

Determinar se o estado de saúde bucal de crianças com Diabetes Mellitus tipo 1 é significativamente diferente de crianças sem diabetes.

Método:

Caso-controle, estudo observacional e analítico. 86 crianças foram avaliadas em dois grupos: DM1) diabeticos tipo 1, de 8 a 12 años, frequentam o Centro Hospitalar Pereira Rossell, sem outra doença sistêmica associada ou tratamento ortodôntico. Control): não diabéticos de 8 a 12 anos, frequentam escola pública, não tomam medicamentos, não têm ortodontia e frequentam os serviços publicos. Variáveis: biofilme; cárie dentária; inflamação gengival; sexo; Idade.

Resultados:

100% de grupos DN1 y Control apresentam biofilme. Caries: 100% Grupo DM1 e 92,9% no Grupo Control (deferencia não significativa). Inflamação gengival: Grupo DM1) 76,7% sangramento sondajem e 60,7% Control (diferencia significativa).

Conclusões:

Dados internacionais da relação Diabetes Mellitus tipo 1 e doença periodontal são confirmados.

Palabras-chave: Diabetes Mellitus; Saúde Bucal; Prevalência; Índice Epidemiológico

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an endocrine, metabolic non-communicable disease affecting a high percentage of the global population; it is also one of the most frequent diseases among children and adolescents. The World Health Organization 1 defines DM as a metabolic disorder with multiple etiologies, characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and an alteration of the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, caused by a defect in the secretion of insulin, in its action, or both. The long-term consequences of DM include the emergence of conditions in different organs or systems, such as the retina, the kidneys, or the cardiovascular system 2. Type 1 DM (DM1) occurs when insulin production is inadequate to prevent hyperglycemia and its consequences. Insulin resistance may increase insulin levels to compensate for it, and diabetes does not occur as long as hyperinsulinemia remedies this situation 3). Several studies (SearchStudy (4) in the United States, DiaMond Project 5, and Eurodiab (6 in Europe and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) 7) have monitored global trends and concluded that the incidence of childhood-onset DM1 is increasing in most countries. Despite geographical, ethnic, and racial differences, the estimated annual growth rate in Europe is 3%, with an even higher figure in younger people 6. Latin America is no exception, with significant increases in DM incidence. A national survey conducted among adults in Uruguay (2004) 8 showed a DM1 prevalence of 16.2%. Deutsch et al. 9 conducted a study with 83 patients aged 12 on average. They were treated at the Diabetes Unit (DU) of the Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell (Pereira Rossell Hospital Center - CHPR), Uruguay. The average onset age was 6 years (9 months-13 years), and the patients were monitored at least once in the DU between July 2012 and July 2013. The internationally agreed minimum checkup frequency is four visits a year 10, with which 66 patients (79%) complied. They concluded that diabetic adolescents require differential care because their medical and emotional needs are different, so they require more follow-up and checkup visits 11.

DM1 is a chronic disease that clearly impacts oral health: tooth loss, gingivitis, periodontitis, and soft tissue pathologies. The severity of oral health-related complications, like those of the rest of the body, are directly related to hyperglycemia and the time elapsed since DM onset. Several clinical studies (Miranda 12, Novotna et al. 13, Lalla et al. 14, Hamman et al. 15, and López del Valle 16) have reported significant DM-related consequences in the oral cavity affecting hard and soft tissues. Some authors have analyzed meal frequency as a risk factor for a higher prevalence of oral pathologies 17. There is evidence 18) linking high blood glucose concentrations to decreased salivary flow and decreased peripheral vascular response, which contributes to biofilm accumulation, caries, and periodontal diseases. In 2015, Gupta confirms that higher blood glucose concentration is directly related to higher salivary glucose concentration 19. Palacios’ 2012 experimental study 20 links diabetic vasculopathy with hyperglycemia. Endothelial dysfunction is an early manifestation of diabetic vasculopathy, but it is still unclear how elevated D-glucose impairs endothelium-mediated vasodilation and manifests clearly at the capillary level. The chronic hyperglycemia observed in patients with DM triggers the formation of systemic inflammatory mediators that circulate throughout the body, including the periodontium. Periodontal cell stimulation triggers a local inflammatory response that amplifies the response caused by periodontal pathogens. In turn, periodontal disease can affect glycemic control in individuals with DM as it is chronic systemic inflammation. Periodontal pathogens, especially G- bacteria, stimulate periodontal tissue cells to synthesize and release local proinflammatory mediators that circulate through the bloodstream and activate the liver’s inflammatory response. This systemic inflammation may reduce the tissue response to insulin hyperglycemia. Karjalainen et al. (1997) 21) investigated tooth decay and its connection with the metabolic control of DM1. They studied 80 children and adolescents and concluded that poor metabolic control of the disease was associated with increased fungal colonies in the oral cavity, creating a risk environment for developing caries and gingivitis. Busato et al. (2012) 22 researched the impact of xerostomia in adolescents with and without DM1 and found a significant association between DM1 and xerostomia. Therefore, this new factor must be monitored to help these patients improve their quality of life.

Scientific evidence indicates that DM1 occurs in over 8% of the pediatric age group and rapidly increases in prevalence and incidence in children and adolescents. However, there is no data in Uruguay on the relationship between DM and oral health-disease.

Objective: To determine if the oral health of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus is significantly different from that of children without diabetes.

Method

Case-control, observational, and analytical study. Lazcano-Ponce’s work 23) was considered for the sample size: the number of controls is greater than the number of cases when the disease or event under study has a prevalence lower than 10%.

Contexts of the research: 1) Diabetes Unit (DU) of the General Pediatric Reference Clinic (PPGR) of the Pereira Rossell Hospital Center (CHPR) 24; it has a multiprofessional and interdisciplinary medical team made up of professors from the School of Medicine and professionals from the State Health Services Administration (ASSE) of the Ministry of Health (MSP). The DU currently includes pediatricians, pediatric endocrinologists, nutritionists, nurses, psychologists, and a dentist (a pediatric dentistry professor) with the conviction that an interdisciplinary and multiprofessional team must address the health of diabetic patients. Care at the DU is personalized, in individual boxes, where the professionals can examine, educate, and motivate each patient and do the required checkups with the adult in charge.

2) The control participants attended Public School No. 172 “José Martí.” Its sociocultural context is similar to that of the patients seen at CHPR (ANEP-CODICEN 2015) 25.

Universe of the study

The study included 86 children divided into two groups: 30 diabetic children aged 8 to 12 treated at the CHPR’s DU (DM1 group), and 56 children aged 18 to 12 without diabetes and attending Public School No. 172 (control group). The clinical oral examinations were performed by a single operator calibrated following the criteria of various dental indexes. The Kappa test yielded an 0.7 inter-operator reproducibility compared to the gold standard, and an 0.85 intra-operator reproducibility. Calibration was performed (5%) throughout data collection.

Inclusion criteria for DM1: children with type I diabetes aged 8 to 12 and treated at the diabetes unit of CHPR. Exclusion criteria: Children with other systemic conditions; children undergoing orthodontic treatment; failure to sign the consent form.

Inclusion criteria for the control group: non-diabetic children aged 8 to 12 treated at ASSE. Exclusion criteria: children with systemic conditions; children undergoing orthodontic treatment; failure to sign the consent form; health care provided by a mutual health institution or private scheme.

Variables

The oral health variables under study were:

- Oral health indicators (for both groups): Caries Detection Index (ICDAS II) and caries-free (yes/no), modified O’Leary Visible Plaque Index (VPI) and presence/absence of biofilm, Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI), and presence/absence of bleeding.

- Sociodemographic variables (for both groups): sex, age, type of dental care received: education, prevention, restoration.

- Variables that characterize the group of diabetic patients: Disease onset/diagnosis, medical checkup frequency.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses of all variables were performed for both groups. The distribution of (qualitative and quantitative) oral health variables was studied to select the relevant statistical tests (parametric or non-parametric) to compare children with DM1 and healthy children. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to contrast the hypothesis of independence between the qualitative health variables (presence/absence) and the presence/absence of diabetes (if the expected frequency is less than five). The differences in the quantitative oral health variables of the diabetic and non-diabetic groups were analyzed with the Student t-test or the Mann-Whitney test. All the data was processed using SPSS statistical software.

Ethical considerations

The authors undertook to keep the data confidential. Parents and responsible adults were asked to sign a free informed consent, and the children’s consent to the examination was obtained. Please note that they were free to refuse to continue with the oral exam at any time. All the children were provided an oral diagnosis, health education, oral hygiene guidelines, and an oral hygiene kit free of charge. The Ethics Committee of the School of Dentistry, Universidad de la República, approved the research project on 19 July 2016, under file number 219/16.

Data collection

Systematization of the clinical exam:

a. biofilm recorded with the Löe Silness Visible Plaque Index (VPI), Bordoni (1992) (26. Code 0 is used to express the absence of biofilm, and 1 is used to express the presence of biofilm: mature plaque visible to the naked eye without using a probe.

b. gingival inflammation recorded with the Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI). Six areas are considered for each tooth: vestibular in its mesial, medial, and distal areas, and lingual/palatal in its medial, mesial, and distal areas 27.

c. the operator performed oral hygiene with a brush, floss, and fluoride toothpaste.

d. the operative field was isolated with cotton rolls, and the tooth surfaces were dried with cotton gauze.

e. the caries index according to ICDAS II 28,29 was recorded for each tooth surface; the lesions were classified according to their activity following Nyvad (1999). The lesions were coded according to Barbachan & Maltz 30.

Results

1) Dental care received. The type of dental care provided to both groups is broken down according to education, prevention, and restoration. - Health education. Of the 30 cases, 12 (40%) reported not having received dental education, while 22 of the 40 controls (59.3%) reported not having received dental education. This difference was not statistically significant according to the Χ2 test (1, N = 84) = 2.868 p = 0.09. - Prevention. Fifteen children out of 30 in the case group and 23 out of 54 (42.6%) in the control group were not provided prevention guidelines. The chi-square test verified that the difference was not statistically significant: Χ2 (1, N = 84) = 0.427 p=0.513. - Dental restoration. Eighteen children (60%) in the case group and 26 children (48.1%) in the control group had dental restoration work done. Both percentages can be considered relatively high. According to the Χ2 test (1, N = 84) = 1.086 p = 0.297 these differences are not statistically significant.

2) Adherence to diabetes treatment was observed by studying checkup frequency; most children attended monthly or bimonthly. The internationally agreed minimum checkup frequency is four a year, which all 30 patients complied with (100%).

3) Time elapsed from the onset of diabetes to the date of the exam: over half the children had been diagnosed with diabetes over three years before.

Oral health indicators

They aim to compare the situation of the DM1 group with the control group.

A. Biofilm All the children in the DM1 and control groups had biofilm. The modified O’Leary Visible Plaque Index yielded a higher mean value in the control group (89.81) than in diabetic patients (71.48). The Mann-Whitney test showed a significantly higher IPV among the healthy patients (median = 100) than among the diabetic patients (median = 93.41) (p = 0.000).

B. Dental caries according to ICDAS II criteria. All the children in the DM1 group and 92.9% of the children in the control group had at least one carious lesion. Table 1 shows the percentages of children in each group with and without carious lesions. We use percentages to compare the groups because the number of healthy children is different from the number of diabetic children.

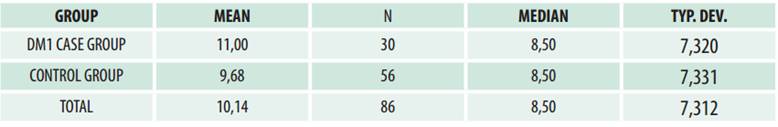

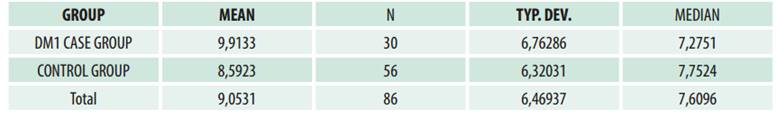

Table 2 shows the number of surfaces with caries according to ICDAS criteria for the children in each group. The mean number of surfaces with carious lesions among the children with diabetes (11.00) was only slightly higher than that of non-diabetics (9.68), and their medians were the same (8.5). The Mann-Whitney test indicated that the number of surfaces with caries was not significantly different between diabetic (median = 8.5) and healthy patients (median = 8.5), U = 750.5 (p = 0.417). If we consider the percentage of surfaces with carious lesions (ICDAS) in relation to the surfaces explored, the results were similar to those obtained with the previous indicator, as shown in Table 3. The mean percentage of surfaces with caries (ICDAS) in diabetic patients (9.91) was slightly higher than that of non-diabetics (8.59). However, the Mann-Whitney test indicated that the percentage of surfaces with caries was not significantly different between diabetic (median = 7.28) and non-diabetic children (median = 7.75) (p = 0.494).

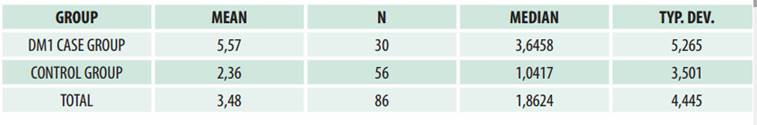

C. Gingival inflammation. Table 4 shows the percentages-within each group-of children with or without gingival bleeding (GBI). In the DM1 group, the percentage of children with bleeding (76.7) is higher than in the control group (60.7), but this difference is not statistically significant according to the Χ2 test (p = 0.136). Table 5 shows differences in both means and medians. The mean GBI of diabetic children (5.57) was higher than that of non-diabetic children (2.36). The Mann-Whitney test indicated that the GBI was significantly higher among diabetic children (median = 3.65) than among the healthy children (median = 1.04), (p = 0.03).

Discussion

According to the literature, the oral health of children with DM1 is affected (31). The multiple studies that have examined the connection between dental caries and DM1 do not report unanimous results. However, most authors agree that gingivitis is more prevalent and severe in children with diabetes and that it appears early 32. The case-control study conducted by López del Valle (Puerto Rico, 2011) 16) in children aged 6 to 12 (25 diabetic and 25 healthy children) reports significant differences when comparing the data collected. It describes higher values in children with DM1 as follows: higher VPI, with a mean value of 2.5 in the DM1 group, and of 0.8 in the control group; a higher number of carious lesions in permanent teeth (DM1 = 1.43, control group = 0.56); higher GBI: DM1 = 23.9%, and control group = 4.2%. A 2007 case-control study by Lalla et al. 14 including children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 (186 diabetic patients and 160 healthy participants) reports significant differences between the groups. It reports higher values in children and adolescents with DM1 as follows: higher VPI (DM = 1.2, and control group = 1.1) and a higher GBI: DM = 23.6%, and control group = 10.2%. However, it reports no significant difference when comparing carious lesions between the groups. Regarding the association between DM1 and gingival bleeding, this study showed statistically significant differences: the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test showed a significantly higher GBI among diabetic patients than in the control group. Following the authors cited above, the two groups were similar in all the independent and dependent variables. This further consolidates the GBI result since the only difference was whether or not the patient had diabetes. Concerning biofilm, the control group presented a higher mean VPI than the DM1 group, and the Mann-Whitney test established the difference as significant. It is internationally agreed that diabetic children should have at least four periodic checkups yearly 10. The 30 patients in this study complied with such a requirement, which clearly helps control the risk factors for dental caries (oral hygiene, meal frequency, etc.). This result further shows that gingival inflammation in diabetic children is connected to their systemic condition. According to these analyses and the results of this study, we agree with Novotna 13) that the connection between DM1 and dental caries in the studies analyzed is inconclusive. In our study, this association was not statistically significant. When analyzing the children’s diet, accounting for the daily number of meals as a caries risk factor was simple for the DM1 group because their diet was planned according to meal frequency and quality. However, we did not have that data on the control group since most healthy children had food and/or juices without restrictions and between meals. DM1 has been proven to be a relevant risk factor for developing periodontal disease 33. A higher prevalence and severity is seen in children suffering from diabetes, which has an early onset. Additionally, there is evidence that gingival inflammation may contribute to the persistence of hyperglycemia, thus causing poor glycemic control in people with DM1 33,34.

Several systematic reviews with meta-analyses have shown the effectiveness of periodontal treatment in improving glycemic control. However, recent criticisms of the methodological limitations of these studies show that further research is needed to draw conclusions on this connection35-38.

Conclusions

The results of this study are the first data collected in Uruguay and help improve care protocols for children and adolescents with or without DM1. The study allows us to analyze the results through an international lens, confirming that children with DM1 have a higher risk of periodontal disease. Dentists and family members should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of DM1 to provide the necessary preventive and therapeutic care. Regarding health promotion, dentists should promote healthy eating habits, oral hygiene, and metabolic control of diabetes early on. Dentists should also be part of the team treating diabetic children to help prevent complications. It is essential to include dental checkups for children in institutional protocols to actively contribute to an early diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Informe mundial sobre la diabetes: resumen de orientación. Abril 2016. Disponible en: http://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/es/ [ Links ]

2. Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Ingelsson E, Lawlor DA, Selvin E, Stampfer M, Stehouwer CD, Lewington S, Pennells L, Thompson A, Sattar N, White IR, Ray KK, Danesh J. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Lancet. 2010; 375 (9733): 2215-22 [ Links ]

3. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41 (Suppl. 1): S13-S27. Disponible en: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/41/Supplement_1/S13.full.pdf [ Links ]

4. Pettitt DJ, Talton J, Dabelea D, Divers J, Imperatore G, Lawrence JM, Liese AD, Linder B, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pihoker C, Saydah SH, Standiford DA, Hamman RF. Prevalence of diabetes in U.S. youth in 2009: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37 (2): 402-8. [ Links ]

5. DiaMond. Diabetes Mondiale Project Group. The DiaMond Project. Disponible en: http://www.pitt.edu/~iml1/diabetes/DIAMOND.html [ Links ]

6. Eurodiab. The Epidemiology and prevention of Diabetes. Int J Epidemiolog 1993;22. Disponible en: https://ec.europa.eu/research/success/en/med/0283e.html [ Links ]

7. International Diabetic Federation. Diabetes in the Young: A global Perspective. IDF diabetes Atlas Four Edition 2010. Disponible en: http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/Diabetes%20in%20the%20Young_1.pdf [ Links ]

8. Ferrero R, García MV. Encuesta de prevalencia de la diabetes en Uruguay. Primera fase: Montevideo. Año 2004. Arch. Med. Int. 2005; 26 (1): 07-12. Disponible en: http://www.prensamedica.com.uy/docs/XXVII-Diabetes.pdf [ Links ]

9. Deutsch I, Pérez R, Pardo L, Lacopino A, Gontade C, Gutiérrez S. Caracterización de la población y evaluación de la calidad asistencial de los niños controlados en la Unidad de Diabetes del Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell. Rev Med Urug 2016; 32 (2): 109-117. [ Links ]

10. Pihoker C, Forsander G, Wolfsdorf J, Wadwa RP, Klingensmith GJ. Structures, processes and outcomes of ambulatory diabetes care. En: International Diabetes federation. Global IDF/ISPAD Guideline for diabetes in childhood and adolescence. Brussels, Belgium: IDF, 2011:42-9. [ Links ]

11. Deutsch I, Pérez R, Pardo L, Lacopino A, Gontade C, Gutiérrez S. Caracterización de la población y evaluación de la calidad asistencial de los niños controlados en la Unidad de Diabetes del Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell. Rev Med Urug 2016; 32 (2): 109-117. [ Links ]

12. Miranda X. Caries e índice de higiene oral en niños con Diabetes Mellitus Tipo 1. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2013; 84 (5): 527-531. [ Links ]

13. Novotna M, Podzimek S, Broukal Z, Lencova E, Duskova J. Periodontal diseases and dental caries in children with type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Mediators Inflamm. 2015; 2015:379626. Disponible en: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/mi/2015/379626/ [ Links ]

14. Lalla E, Cheng B, Lal S, Kaplan S, Softness B, Greenberg E, Goland RS, Lamster IB. Diabetes mellitus promotes periodontal destruction in children. J Clin Periodontol. 2007; 34: 294-298. [ Links ]

15. Hamman R, Bell R, Dabelea D, D'Agostino R. Jr, Dolan L, Imperatore G, Lawrence JM, Linder B, Marcovina S, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pihoker C, Rodriguez B, Saydah S. The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study: Rationale, Findings and Future Directions. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37 (12): 3336-3344. [ Links ]

16. López del Valle LPR. Comparing the Oral Health Status of Diabetic and Non-Diabetic children from Puerto Rico: a Case-Control Pilot Study. Health Sci J. 2011; 30 (3):123-127. [ Links ]

17. Bassir L, Amani R, Khaneh Masjedi M, Ahangarpor F. Relationship between dietary patterns and dental health in Type 1 Diabetic children compared with healthy controls. Iran Red CrescentMed J. 2014; 16 (1):e9684. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3964440/ [ Links ]

18. Ribeiro Andrades KM, Bento de Oliveira G, de Castro Vila LF, de Los Rios Odebrecht M, Machado Miguel LC. Asociación de los índices de glucemia, hiposalivación y xerostomía en pacientes diabéticos Tipo 1. Int. J. Odontostomat. 2011; 5 (2):185-190. [ Links ]

19. Gupta S. J. Comparison of salivary and serum glucose levels in diabetic patients. Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015; 9 (1): 91-6. [ Links ]

20. Palacios E. Disfunción endotelial asociada a la diabetes mellitus. Interacción entre inflamación e hiperglucemia. Tesis. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. 2012. Disponible en:https://repositorio.uam.es/bitstream/handle/10486/9925/50855_palacios%20rosas%20erika.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

21. Karjalainen KM, Knuuttila MLE, Käär ML: Relationship between caries and level of metabolic balance in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Caries Research 1997; 31:13-8. [ Links ]

22. Busato IM, Ignacio SA, Brancher JA, Moyses ST, Azevedo-Alanis LR. Impact of clinical status and salivary conditions on xerostomia and oral health-related quality of life of adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012; 40: 62-69. [ Links ]

23. Lazcano-Ponce E, Salazar-Martínez E, Hernández-Ávila M. Estudios epidemiológicos de casos y controles. Fundamento teórico, variantes y aplicaciones. Salud Pública Mex. 2001; 43: 135-50. [ Links ]

24. López Jordi MC, Szwarc E. Experiencia educativa para el abordaje interdisciplinario de niños y adolescentes con Diabetes Mellitus. Conference Paper. IX CLIOA 2015 . [ Links ]

25. Uruguay. Consejo de Educación Inicial y Primaria (CEIP). Dpto de Investigación y Estadística Educativa (DIEE). Relevamiento de característica sociocultural de las escuelas públicas 2015. Recuperado de: http://www.ceip.edu.uy/documentos/2016/varios/Anticipacion_%20resultado_Relevamiento.pdf [ Links ]

26. Bordoni N, Doño R, Miraschi C. PRECONC. Organización Panamericana de la Salud 1992. [ Links ]

27. Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975; 25:229-35. [ Links ]

28. ICDAS Foundation. Internacional Caries Detection and Assesment System. 2016. Disponible en: https:// icdas.org/downloads. [ Links ]

29. Ekstrand KR, Gimenez T, Ferreira FR, Mendes F, Braga M. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System- ICDAS. A systemic review. Caries Res 2018; 52: 406-419. [ Links ]

30. Barbachan E, Silva B, Maltz M. Prevalence of dental caries, gingivitis, and fluorosis in 12-years-old students from Porto Alegre- RS Brazil 1998/1999.Pesqui Odontol. Bras. 2001;15 (3): 208-14. [ Links ]

32. Palomer L, García H. ¿Es importante la salud oral en los niños con diabetes? Rev Chil Pediatr. 2010; 81 (1): 64-70. [ Links ]

33. Mealey BL, Ocampo GL. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. Periodontol. 2000. 2017; 44: 127-153. [ Links ]

34. Albandar JM, Susin C, Hughes FJ. Manifestations od systemic disease and conditions that affect the periodontal attachment apparatus: Case definitions and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol. 2018;89 (Suppl 1):S183-S203. [ Links ]

35. Carneiro VL, Fraiz FC, Ferreira Fde M, Pintarelli TP, Oliveira AC, Boguszewski MC. The influence of glycemic control on the oral health of children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus type 1. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2015; 59:535-540. [ Links ]

36. Faggion CM Jr, Cullinan MP, Atieh M. An overview of systematic reviews on the effectiveness of periodontal treatment to improve glycemic control. J Periodontal Res. 2016; 51: 716-725. [ Links ]

37. Siudikiene J, Machiulskiene V, Nyvad B, Tenovuo J, Nedzelskiene I. Dental caries and salivary status in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus, related to the metabolic control of the disease. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006; 114: 8-14. [ Links ]

38. Gómez-Gómez M, Danglot-Banck C, Huerta Alvarado SG, García de la Torre G. El estudio de casos y controles: su diseño, análisis e interpretación, en investigación clínica. Rev Mex Pediatr. 2003; 70 (5): 257-263. [ Links ]

Authorship contribution: 1. Conception and design of study 2. Acquisition of data 3. Data analysis 4. Discussion of results 5. Drafting of the manuscript 6. Approval of the final version of the manuscript. AT has contributed in 1,2,3,4,5,6. GV has contributed in 1,3,4,5,6. LP has contributed in 1,4,5.6. MCLJ has contributed in 1,4,5.6.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Received: September 24, 2020; Accepted: April 07, 2021

text in

text in