Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Odontoestomatología

Print version ISSN 0797-0374On-line version ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.23 no.38 Montevideo 2021 Epub Sep 30, 2021

https://doi.org/10.22592/ode2021n37e209

Research

Impact of the number of periodic dental checkups on oral health at a university pediatric dentistry clinic

1Cátedra de Odontopediatría, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República, Uruguay. drasilviasosatorices@gmail.com

2Servicio de Epidemiología y Estadística. Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República. Uruguay.

3Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

4Cátedra de Odontopediatría, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

The Pediatric Dentistry Clinic at the School of Dentistry, Universidad de la República, has a care model that focuses on promotion, health education and rehabilitation, and aims to support health control and maintenance. There is no information on the impact of periodic checkups.

Objective:

To evaluate the association between the number of checkups and oral health in children aged between 5 and 10. Cross-sectional, descriptive (2017-18) and retrospective (up to 2014) study in two subpopulations: G1 = checkups, and G2 = first visit. We evaluated the differences in the number of teeth affected.

Results:

The sample included 115 children: 44 in G1 and 71 in G2. All of them had biofilm. G1 presented significantly lower values regarding visible plaque index (VPI) (>20%) (p < 0.001) and cavitated lesions (p < 0.001). G1 members, who had attended two or more checkups, had 2.6 initial lesions on average, and G2 members, 4.5 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Children who had attended two or more checkups had better oral health than those seeking care for the first time. This confirms the importance of scheduled checkups for maintaining oral health.

Keywords: Oral health; care model; health reassessment; dental controls; dental checkups

La Clínica de Odontopediatría desarrolla un modelo de atención con énfasis en promoción, educación y rehabilitación destacándose su control y mantenimiento. No hay información sobre el impacto de los controles periódicos.

Objetivo:

Evaluar la asociación del número de controles y la salud bucal de niños entre 5 y 10 años. Estudio transversal, descriptivo (2017-18) y retrospectivo (hasta 2014) en dos subpoblaciones: G1=controles y G2=primera vez, evaluando diferencias de piezas afectadas

Resultados:

115 niños, 44 en G1 y 71 en G2. El 100% presentaron biopelícula. G1 presentó un valor significativamente menor del IPV>20% (p<0.001), de lesiones cavitadas (p<0.001). G1 con 2 o más controles el promedio de lesiones iniciales fue de 2,6 y G2 de 4,5 (p<0.001).

Conclusiones:

Los niños con dos o más controles presentaron mejor situación de salud bucal que quienes consultaron por primera vez. Se confirma la importancia del control programado para el mantenimiento de la salud bucal.

Palabras clave: Salud oral; modelo de atención; revaluación de la salud; controles odontológicos; chequeos dentales

A Clínica de Odontologia Pediátrica desenvolve um modelo de cuidado com ênfase na promoção, educação em saúde e reabilitação destacando seu controle e manutenção. Não há informações que sustentem o impacto que os controles regulares.

Objetivo:

Avaliar a associação do número de controles anuais e da saúde bucal de crianças entre 5 e 10 anos. Estudo transversal e descritivo (2017-18) e retrospectiva (até 2014) em duas subpopulações: G1-controle e G2-primeira vez.

Resultados:

115 crianzas: G1-44 e G2-71. 100% do de crianças apresentaram biofilme. G1 apresentou valor de IPV>20% e lesões cavitadas significativamente menor (p<0,001). G1 com 2 ou mais controles a média de lesões iniciais foi de 2,6 e no G2 4,5 (p <0,001).

Conclusões:

Crianças que assistem a 2 ou mais controles têm uma melhor situação de saúde bucal em comparação com aquelas que consultam pela primeira vez. Confirma-se a importância do controle programado para manutenção da saúde bucal.

Keywords: Saúde bucal; modelo de atenção; reavaliação da saúde; controles dentários; exames odontológicos

Introduction

The Pediatric Dentistry Clinic of the School of Dentistry, Universidad de la República has a care model that focuses on promotion, the importance of education for the health of children and/or adolescents and their family group, the control of the most prevalent oral diseases and rehabilitation procedures within a preventive philosophy where checkups and maintenance prevail. This study addresses an in-depth, current, and retrospective analysis of patients aged between 5 and 10 who attended the Pediatric Dentistry Clinic in 2017 and part of 2018. It also focuses on the relationship between the reassessment or recall examination and the children’s oral health. Bordoni et al. 1 state that oral health reassessment mainly aims to monitor diseases caused by dental plaque or biofilm, factors that are highly dependent on personal behavior. Deep 2 states that screening provides ongoing care to help preserve oral health and plan for future treatment, thereby halting the progress and effects of oral diseases as early as possible. Wange & Holts 3 report on the need to monitor new lesions regularly and to follow up on tooth development stages in children to ensure that interventions are appropriate and timely and to detect oral manifestations of systemic diseases early, among other things. Screening provides opportunities for counseling, motivating, and reinforcing prevention, which helps maintain a positive attitude towards health. Two studies state that the ideal recall interval differs between countries and health systems, although an interval of 6 months has been accepted as ideal 4-5. Each child has different clinical conditions and treatment needs, which requires dentists to plan control, prevention, and differentiated treatment strategies based on each patient’s risk assessment and disease activity. This helps provide effective prevention and treatment plans and also prevents under- or over-treatment. However, there is no conclusive scientific evidence on which is a reliable recall interval, and the benefits of examining all patients every six months has been questioned. Mettes 6) conducted a study (Cochrane Library) and concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine the potential benefits of the dental checkup interval confidently. In 2004, U.K.’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 7 established that a recall interval of less than 3 months and more than 12 months is inadequate. This guide considers people’s well-being, general health and preventive habits, caries incidence, and periodontal health. It aims to help improve patients’ quality of life and reduce the morbidity associated with oral disease. These are NICE’s recommended intervals between oral health reviews:

- The shortest recall interval for all patients should be 3 months. (A recall interval of less than 3 months is not normally needed for a routine dental recall. In children, it may be necessary in a particular case, emergency, or episodes requiring special care.)

- The longest recall interval for patients younger than 18 should be 12 months. (There is evidence that the rate of progression of dental caries can be more rapid in children and adolescents than in older people, and tooth development should also be evaluated.)

- The longest interval between oral health reviews for patients aged 18 and older should be 24 months. Intervals longer than 24 months are undesirable because they could diminish the professional relationship between dentist and patient, and people’s lifestyles may change in such a long time.

- The dentist should discuss the recommended recall interval with the patient, explaining the reasons behind it and if it will vary over time.

The appropriate interval should be analyzed for each patient according to risk and activity 8. The importance of periodic monitoring in health care leads public and private health services to conduct oral health reviews as routine treatments as they allow dentists to plan prevention strategies after reassessing the patient’s health, and more effective therapies with a minimal risk of under- or over-treatment.

Objectives

General objective. To evaluate the association between the number of annual dental checkups and the oral health of patients treated at the Pediatric Dentistry Clinic, FO, Udelar.

Specific objectives. - To quantify dental plaque, caries, and gingivitis among the children attending the established periodic checkups and the children population seeking care for the first time. - To evaluate the disease gradient of the dependent variables (biofilm, dental caries, and gingival inflammation) and independent variables (reason for consultation, sex, age, number of checkups, health coverage, brushing frequency) with periodic checkups.

Methodology

We conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical design study on all the patients aged between 5 and 10 who were seen and evaluated in 2017-2018 and a retrospective analysis until 2014, at the Pediatric Dentistry Clinic, School of Dentistry, Universidad de la República.

Data collection. Data was collected between May-October 2017 and February 2018. The study also included the retrospective analysis of the medical records of patients seeking care between 2014 and 2017, a questionnaire, and a clinical examination, described below. Dental history: the data collected included date of birth, sex, year when care at the clinic started, and the number of annual periodic checkups. We applied a structured questionnaire to the parents or guardians of the children selected. The questionnaire included questions on socioeconomic characteristics and health coverage. The clinical examination was performed by a single trained and calibrated operator (Kappa and intra-examiner reproducibility = 0.72) in the dental unit of the clinic with a flat mirror without magnification and a WHO CPI millimeter probe.

Study population. Patients aged between 5 and 10 without systemic conditions seen for a dental checkup (G1) and patients seeking care for the first time (G2) at the Pediatric Dentistry Clinic between April 2017 and February 2018 were included. Patients with systemic conditions and whose parents/guardians did not sign the informed consent form were excluded.

Oral health study variables:

Dependent variables

A) Biofilm evaluated with Löe & Silness’s simplified Visible Plaque Index (VPI) 9, where code 0 = no plaque; 1 = visible plaque. VPI>20% was used to determine biofilm accumulation incompatible with health.

B) Prevalence and extent of dental caries were determined with the DMF and ICDAS indexes 10,11. The surfaces were assigned codes: 0- sound surface; 1- active non-cavitated lesion; 2- inactive non-caries lesion; 3- early enamel lesion; 4- shadow; 5- dentinal lesion; 6- coronal destruction; 7- missing due to caries; 8- missing due to trauma; 9- unerupted; 10- restoration; 11- restoration affected; 12- restoration with an underlying lesion or that should be replaced. The operational procedures for analyzing the prevalence of dental caries statistically agree that DMF+3 = ICDAS values 3, 5, 6 (moderate lesions).

C) Gingival inflammation determined through the Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) 12 as per these codes: 0 - no marginal bleeding on probing; 1 -

marginal bleeding on probing.

Independent variables

A) Reason for consultation Code 0 - seeks care at the clinic for the first time; Code 1 - dental checkup; Code 2 - seeks emergency care.

B) Sex: 0- female; 1- male.

C) Number of checkups: Codes: 1= one checkup; 2= two or more checkups.

D) Health coverage: Codes 0-2 - public sector: (0- ASSE (National Health Administration); 1- Military Health Program; 2- Police Health Program; and 3-4 Private sector (3- FONASA (National Healthcare Fund) and 4- Private insurance schemes)

E) Brushing frequency: Code 1- Insufficient (< twice a day); 2- Sufficient (≥ twice a day).

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the School of Dentistry, Universidad de la República, approved the research project under file number 251/16. The research team undertook to keep the data confidential. As per Law 18335/008, Decree 379/008, and Ordinance 2010, the guardians were informed about the objectives of the study and were asked to sign the free, informed consent and to allow the researchers to work with their child’s dental history. Additionally, the child’s permission to be examined was requested (no signature).

Statistical analysis

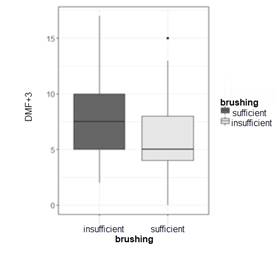

The data was analyzed with R Core Team 2019. The quantitative variables were described using averages, while proportions were calculated for binary variables. Box plots were used to compare the distribution of the quantitative variables in the groups formed by the qualitative variables. The association between oral health and the number of checkups was evaluated in both subpopulations using the nonparametric Wilcoxon test for independent groups (for quantitative variables). Fisher’s exact tests were used for binary variables, and odds ratios (OR) were calculated 13. A 5% statistical significance was determined.

Hypothesis. The oral health of children who attend regular checkups and those seeking care for the first time is different.

Results

A total of 115 children participated: 44 in G1, and 71 in G2. The distribution of the total number of children by year of birth was balanced: 60 children born between 2007 and 2009 and 55 born between 2010 and 2012. The total sample included 54 girls and 61 boys. The two groups had a balanced sex distribution: 22 girls and 22 boys in G1 (50% each), and 32 girls (45%) and 39 (55%) boys in G2. The distribution of the number of checkups recorded showed that 93.2% of the children had attended one, two, or three checkups, while 6.8% had attended four checkups. The distribution of the number of checkups in G1 showed that 36.4% had attended one checkup, 34.1% two, 22.7% three, and the remaining 6.8%, four. Regarding health coverage, 35.7% had private health coverage, and 64.3% had public health coverage.

Variable distribution in both groups

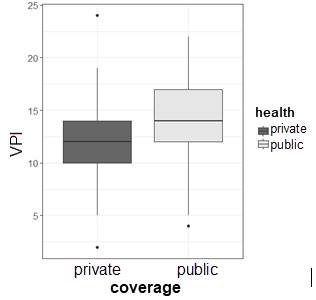

A) Biofilm. Cumulative VPI was much higher in the children treated for the first time than those who attended regular checkups (66%-18%, p < 0.001). Regarding the accumulation of biofilm incompatible with health (VPI > 20%), boys had a higher rate than girls, although the difference was not significant (54% - 41%, p = 0.191). The average visible plaque of children with public sector health coverage was significantly higher than those treated in the private sector (14.1% - 12.1%, p = 0.007). (Chart 1).

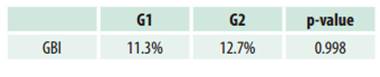

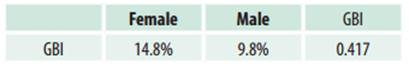

B) Gingival inflammation. The prevalence of gingival bleeding was analyzed according to the reason for consultation. It was slightly higher in G2 (Table 1). Regarding sex, gingival bleeding prevalence was higher in the girls (Table 2).

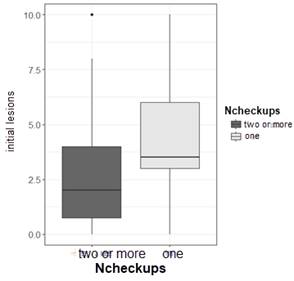

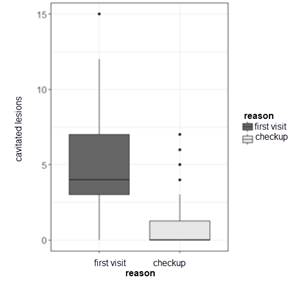

C) Dental caries. Of the children, 99.1% had at least one caries lesion, 70.4% of which were cavitated. When studying the association between current caries and the reason for consultation, we found that G2 had more teeth with caries lesions than G1 (p < 0.001) (Chart 2). Regarding the association between initial lesions and the number of checkups, the group with two or more checkups had a lower average number of lesions (p = 0.033) (Chart 3).

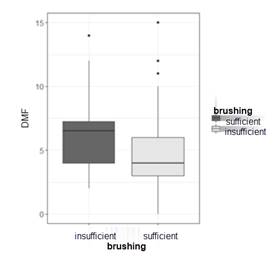

The number of carious lesions according to the DMFT index was higher in G2 (4.8 - 1.1, p < 0.001). The percentage of caries lesions in G1 was lower than in G2 (38% - 90%, p < 0.001) (Chart 4). Cavitated lesions were 14.52 times more likely to progress in G2 (OR: 5.4 - 39.02, CI 95%). Similar behavior was observed in the association between untreated lesions and the reason for consultation, resulting in a much higher mean value in G2 (7.2 - 4.1, p < 0.001) (Chart 5). Charts 6 and 7 show that G1 children with two or more checkups behave differently regarding initial lesions. Lesions do not progress in G1 and do progress in G2 because there are more cavitated lesions. The average number of teeth with caries lesions was 6.3 for children who brushed insufficiently and 4.6 for those with sufficient brushing. The ratio of brushing to DMFT+3 yielded a mean value of 7.7 for children with insufficient brushing and 5.7 when brushing was sufficient (p < 0.025).

Discussion

One of the pillars in pediatric dentistry for maintaining oral health is patient recall at an interval agreed on with the treating dentist to assess the patient’s oral health. In 2013, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry 14) stated that examination intervals should be determined according to each patient’s individual needs, considering caries incidence, preservation of restorations, periodontal health, preventive habits, general health, and impact on the quality of life of individuals, therefore preventing tooth loss, pain, and anxiety. Davenport et al. 15 state that complex modifying factors interact in developing and controlling oral diseases, including age, socioeconomic level, fluoride use, and dental care. Although the evidence shows that mechanical oral hygiene is essential to prevent and control caries and periodontal disease, we agree with Maltz et al. 16) that most individuals do not achieve optimal biofilm control. In this study, which included 115 children (44 in G1 and 71 in G2), all the participants had biofilm, proving the importance of periodic checkups to monitor the children’s oral health and help develop lasting healthy habits. Oral hygiene procedures, which help control dental caries and fluoride-associated disease, are two priority components of care according to the minimum intervention criteria 17. Furthermore, this study showed that the children attending the clinic for the first time had a more significant accumulation of visible plaque. This agrees with Maltz 18, who confirms that regular monitoring of plaque control should be included in pediatric dentistry checkups. The correlation between unhealthy biofilm accumulation and public health coverage yields significantly higher values. We could consider that the child’s health coverage represents the family’s socioeconomic level to some extent. Therefore, we could generalize that the entire family has poorer oral health. According to the U.S. National Institute of Health 19, low socioeconomic status is associated with limited access to services, limited oral health aspirations, low self-efficacy, and health behaviors that increase caries risk. Therefore, maintaining oral health requires periodic health checkups. There is little consistent evidence on the effect of periodic checkups on gingival bleeding, gingivitis, and even periodontitis. In this study, the diagnosis of gingival inflammation was correlated with the presence or absence of gingival bleeding 12, and a higher value, although not significant, was observed in first-time attendees. It is important to analyze the various causes that cause gingival inflammation in our study population: a highly dynamic stage of tooth replacement (mobility, resorption) and a phase of active eruption of multiple teeth, which triggers the inflammation of peridental tissues. Clearly, when persistent dental plaque and insufficient brushing combine, the resulting inflammation signs are more noticeable. This agrees with Andrade et al. 20) , who refer to the etiology of gingival inflammation in children and adolescents and say that dental plaque, tooth eruption and exfoliation, tooth replacement, and hormonal factors explain gingival inflammation. The scientific literature suggests an association between the effect of scheduled checkups and caries, tooth loss, and fillings in deciduous, mixed, and permanent dentition, although the results are inconsistent (8, 14, 15). In this study, the percentage of children with cavitated caries lesions was lower in children who attended periodic checkups, and the mean number of teeth with caries lesions was also lower compared to the group of children seeking care for the first time. These results indicate that G2 children are sicker, and lesions could progress freely if they go untreated. Additionally, initial caries lesions are also found in greater numbers in G2 than in G1, and when correlated with the number of checkups, the children who had attended two or more checkups had better oral health, and the initial lesions did not progress. The results of correlating brushing and dental caries are consistent with the findings of Tickle et al. 21, who concluded that 5-year-old children who did not visit the dentist regularly had a higher dmft index: more missing and decayed teeth and fewer filled teeth. They state that regular dental care significantly affects the dmft index, so children treated under preventive health programs have better oral health. Currently, it is believed 22-23) that if caries-free children have the necessary fluoride intake, they are unlikely to develop deep lesions within six months after the reassessment examination. In agreement with our study, Abanto et al. 24) evaluated the effectiveness of a preventive-care program in 351 children aged 1 to 12 and established that for each checkup, there was a 77% reduction in the risk of new caries lesions (94.8% of children had no new lesions) and also a significantly higher probability of initial active caries lesions regressing. As in our study, children who had previously visited the dentist had fewer active caries lesions than children who had never sought dental care. This supports the notion that a preventive-care program in pediatric dentistry should have two fundamental purposes:

1) to ensure that children remain free of caries, and

2) to help halt and/or reverse carious processes in children who already have the disease.

Clarkson et al. 25) state the need for further research to improve and support patient-dentist communication to establish a variable check-up interval based on the risk diagnosis and to understand the role of recovery with short- and long-term, risk-based decision making in order to monitor and maintain people’s health.

Finally, the recent 74th WHO Assembly held in May 2021 confirms this philosophy by establishing the need to refocus the traditional curative approach towards a promotion and prevention approach that includes early risk identification, comprehensive and inclusive care, taking into account all stakeholders to help improve the oral health of the population and to have a positive impact on general health 26.

Conclusions

This is the first study that evaluates the efficacy of a preventive-care program at the School of Dentistry, Universidad de la República, based on a philosophy of minimal intervention with periodic checkups. In this study, the group of children who had attended two or more checkups had better oral health. Therefore, we can conclude that their lesions did not progress, while those treated for the first time were sicker, and the disease was progressing freely. Children that participate in a preventive health program have better chances of maintaining their oral health. It is essential to agree on recall intervals based on different situations. Each child has different clinical conditions and treatment needs, so dentists must plan recall strategies based on the risk assessment of each patient to provide efficient preventive, non-operative, and operative treatments and avoid under- or over-treatment. Assessing dental care programs provides relevant data for decision-making and for public and private health services to routinely implement periodic checkups.

REFERENCES

1. Bordoni N, Escobar A, Castilla R. Capítulo 42. En: Odontología Pediátrica. La salud bucal del niño y del adolescente en el mundo actual. 1º Ed. Buenos Aires: Médica Panamericana, 2010. 881p [ Links ]

2. Deep P. Screening for Common Oral Diseases. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000; 66:298-9. [ Links ]

3. Wange NJ, Holts D. Individualizing recall intervals in child dental care. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 1995; 23 (1): 1-7. [ Links ]

4. Frame PS, Sawai R, Bowen WH, Meyerowitz C. Preventive dentistry: practitioners' recommendations for low-risk patients compared with scientific evidence and practice guidelines. Am J of Prev Med. 2000; 18 (2): 159-62. [ Links ]

5. Scott G, Brodeur JM, Olivier M, Benigeri M. Parental factors associated with regular use of dental services by second-year secondary school students in Quebec. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002; 68 (10): 604-8. [ Links ]

6. Mettes D. Insufficient evidence to support or refute the need for 6-monthly dental check-ups. What is the optimal recall frequency between dental checks? Evid Based Dent. 2005; 6 (3): 62-3. [ Links ]

7. NICE Guidance. Dental Checks: intervals between oral health reviews. October 2004. Disponible en: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg19 [ Links ]

8. Gibson C, Moosajee A. Selecting appropriate recall intervals for patients in general dental practice an audit project to categorize patients according to risk. Dental Update. 2008; 35 (3): 188-190, 193-194. [ Links ]

9. Bordoni N, Doño R, Miraschi C. Preconc. Organización Panamericana de la Salud 1992. [ Links ]

10. ICDAS Foundation. International Caries Detection and Assessment System. 2016. Disponible en: https:// icdas.org/downloads. [ Links ]

11. Ekstrand KR, Gimenez T, Ferreira FR, Mendes F, Braga M. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System- ICDAS. A systemic review. Caries Res. 2018; 52 (5): 406-419. [ Links ]

12. Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975; 25 (4): 229-35. [ Links ]

13. The R Project for Statistical Computing (OR), A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL: https://www.R project.org/ [ Links ]

14. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AADP). Guideline on Periodicity of Examination, Preventive Dental Services, Anticipatory Guidance/Counseling, and Oral Treatment for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 2013. Disponible en: http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_Periodicity.pdf [ Links ]

15. Davenport C, Elley K, Salas C, Taylor-Weetman CL, Fry-Smith A, Bryan S, Taylor R. The clinic effectiveness and cost of routine dental checks. NIHR Health Technology Assessment program. health Technol Access 2003. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0015130/ [ Links ]

16. Maltz M, Jardim JJ, Alves LS. Health promotion and dental caries. Braz Oral Res. 2010; 24 (Suppl 1): 18-25. [ Links ]

17. Walsh L J, Brostek A M. Minimum intervention dentistry principles and objectives. Aust Dent J. 2013; 58 (Suppl 1): 3-16 [ Links ]

18. Maltz M, Andaló Tenuta LM, Groisman S, Cury JA. Cariología: Conceitos Básicos, Diagnóstico e Tratamento nao Restaurador. Publisher: 1era ed. Porto Alegre: Artes Medicas; 2016 144p [ Links ]

19. US. Dept of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2010: midcourse review. Disponible en: http://www.healthypeople.gov/data/midcourse [ Links ]

20. Andrade E, Lorenzo S, Álvarez L, Fabruccini A, García MV, Mayol M, Drescher A, Asquino N, Bueno L, Rössing CK. Epidemiología de las Enfermedades Periodontales en el Uruguay. Pasado y presente. Odontoestomatología. 2017; 19(30): 14-28 [ Links ]

21. Tickle M, Williams M, Jenner T, Blinkhorn A. The effects of socioeconomic status and dental attendance on dental caries' experience, and treatment patterns in 5- year-old children. Br Dent J. 1999; 186 (3): 135-7. [ Links ]

22. Mejàre I, Källest l C, Stenlund H. Incidence and progression of approximal caries from 11 to 22 years of age in Sweden: A prospective radiographic study. Caries Res. 1999; 33 (2): 93-100. [ Links ]

23. Lith A, Lindstrand C, Gröndahl HG. Caries development in a young population managed by a restrictive attitude to radiography and operative intervention: II. A study at the surface level. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002; 31(4): 232-9. [ Links ]

24. Abanto J, Celiberti P, Minatel M, Alvarez E, Cordeschi T, Haddad A E, Bonecker M. Effectiveness of preventive program based on caries risk assessment and recall intervals on incidence and regression of initial caries lesions in children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015; 25(4): 291-9 [ Links ]

25. Clarkson JE, Pitts NB, Goulao B, Boyers D, Ramsay CR, Floate R, et al. Risk-based, 6-monthly and 24-monthly dental check-ups for adults: the INTERVAL three-arm RCT. Health Technol Assess 2020;24(60). [ Links ]

26. WHO 2021. Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly. EB148/SR/8. Mayo 2021. Disponible en: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB148/B148_8-en.pdf [ Links ]

Authorship contribution: 1. Conception and design of study 2. Acquisition of data 3. Data analysis 4. Discussion of results 5. Drafting of the manuscript 6. Approval of the final version of the manuscript. SST has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. RA has contributed in: 1, 3, 4, and 6. FM has contributed in: 1, 3, 4, and 6. MCLJ has contributed in: 5 and 6. SC has contributed in: 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Received: March 18, 2021; Accepted: June 28, 2021

text in

text in