Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Odontoestomatología

Print version ISSN 0797-0374On-line version ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.17 no.26 Montevideo Nov. 2015

Riadi-Cornejo, Consuelo*, Escalona-Lagos, Ximena**, Avalos-Lara, Patricia***, Díaz-Narváez, Víctor Patricio ****

* Dental Surgeon. MA. Specialist in Pediatric Dentistry. Centro de Salud Familiar, Municipality of Lo Barnechea. Santiago. Chile.

** Dental Surgeon. Specialist in Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatric Dentistry Department. School of Dentistry, Universidad Finis Terrae. Santiago. Chile.

** Professor. Dental Surgeon. Specialist in Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatric Dentistry Department. School of Dentistry, Universidad Finis Terrae. Santiago. Chile.

*** Research Professor. School of Dentistry. Universidad San Sebastián. Downtown Santiago. Metropolitan Area. Chile.

****Associate Researcher. Universidad Autónoma de Chile. Providencia. Downtown Santiago. Metropolitan Area. Chile.

Abstract

Objective. The aim of this study was to assess the educational effect of the Comprehenisve Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women implemented at CESFAM (Family Health Center) in the Municipality of Lo Barnechea, Chile, since 2010, on the oral health of their children at 2 years of age. Materials and methods. Descriptive, observational and cross-sectional study. Information from 129 children attending their first dental care appointment was analyzed. The presence of poor dental habits, tooth decay and cariogenic risk level was determined. The sample was analyzed according to independent variables: mothers who had been discharged from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan, mothers who had not participated in the plan and a subgroup of the first one where mothers had a mother-child dental check-up when the infant turned 6 months. Results. There were no significant differences regarding the presence of decay or poor habits in the groups studied. There was a significant association between the mothers who had been discharged from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan and lower daily consumption (p <0.005) of sugary foods. The group that had been discharged from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan and had had a mother child check-up when the infant was 6 months old had a high significant association with low cariogenic risk (p <0.005). Conclusion. No significant differences between the groups were found in most of the variables studied. This proves that the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Woman implemented in CESFAM, Municipality of Lo Barnechea, Chile, does not have the expected effect regarding the improvement of the children’s oral health at 2 years of age.

Keywords: oral health, prevention, education.

Received on: 26 Nov 14 – Accepted on: 24 Jun 15

Introduction

Poor dental habits that cause oral caries and dentoskeletal deformities can be prevented by educating the population. Pregnant women have shown to be more sensitive and highly motivated to learn about their health and the health of their child (1-4). Furthermore, the oral health of the mother will influence their children’s risk of developing early dental caries due to the transmission of cariogenic bacteria, as well as behaviors that favor the development of oral diseases (5-12).

Maternal oral health care has always been a priority for the Chilean Ministry of Health (MINSAL). Primary Health Care programs have always promoted dental care for this particular group and, since July 2010, pregnant women’s comprehensive oral health is guaranteed, which allows them to access these services and improves the coverage of pregnant women receiving comprehensive oral health care. This health plan allocates resources so that all pregnant women have access to proper dental care by a dental surgeon, where measures are taken to educate, prevent, recover and rehabilitate the expectant mother’s oral health, until the woman has been given the Comprehensive Discharge, which is granted once the patient’s oral health is recovered (13). This plan has a strong educational component which aims to reinforce knowledge on oral disease risk, so as to prevent it and to promote proper care from the moment the baby is born. However, the effect this plan has on the oral health of children is unknown; in particular the educational effect on their oral health indicators. The aim of this study was to assess the educational effect of the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women on the oral health of their children at 2 years of age, on the population registered at CESFAM (Family Health Center) in the Municipality of Lo Barnechea. Santiago. Chile.

Materials and methods

A descriptive, observational and cross-sectional study was designed (14). The target population were all the 2-year-olds registered at CESFAM in Lo Barnechea, who had not yet attended their first dental check-up (n=234), which, under ministerial ordinance, should take place at this age (15). Generally, the child is referred to their first dental visit after the well-baby check-up performed by a nurse to all 2-year-olds. In addition to this scheduling method and in order to increase the target population, appointments were scheduled by calling those patients who had failed to attend the well-baby check-up with the nurse.

The children who attended with a caregiver did so voluntarily. A clinical intraoral examination was performed with basic examination equipment, compressed air and light from the dental equipment. All the exams were performed by an operator in a period of two months. The caregiver was interviewed in order to identify the oral habits in the child’s daily routine, and this information was used to fill out the clinical record (Annex 1). They were handed an informed consent form and, if they stated they understood the information provided, they were requested to sign the document (Annex 2). The sample exclusion criteria were the following: children who had already been admitted to the dental plan before, children who had not attended with their mother or primary caregiver (PC), children whose mother or PC had not signed the informed consent. As a result of this process, a total of 129 children took part in this study.

The following variables dependent on the children were set for the purpose of this study: deft index (following WHO guidelines, only carious lesions were recorded as caries) (16), presence of poor dental habits: use of pacifier as a distraction, nighttime breastfeeding and bottle-feeding (based on the Chilean Ministry of Public Health clinical guidelines) (17) and cariogenic risk level as determined by the CAT form for 0-5 year-olds (Caries Risk Assessment Tool) developed by the AAPD (American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry) which classifies the patient at a low, moderate or high cariogenic risk depending on the presence or absence of the 14 variables listed on Annex 2 (18). For the purpose of this study, 7 of those variables were analyzed as they were relevant to assess cariogenic risk in the target population.

Out of the total sample under study, data on each child were classified into groups based on the following criteria: 43 children whose mothers did not take part in the Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women and 86 children whose mothers had been discharged from this plan. Of these 86, 45 had also attended a mother-child dental check-up. This check-up, which takes place at CESFAM in the Municipality of Lo Barnechea, applies to women who have been discharged from the plan once the child turns 6 months. Its aim is to reinforce education and the prevention of poor dental habits. In addition, among the independent variables we considered were: the mother’s educational level, number of children and socioeconomic level (since Chile lacks a standardized classification, for the purpose of this study it will be determined following the Chilean National Health Fund criteria: FONASA, which classifies each person into different categories depending on their income and number of dependent relatives) (19). This study was approved by the ethics committee of the El Salvador Hospital on April 15th, 2014 (Annex 3).

Statistical Analysis. The sample’s deft index was obtained by calculating the mean and standard deviation of the population that presented dental caries. The data observed for the dependent and independent variables were analyzed using the chi-square test (χ2) in contingency tables to find a correlation between the variables mentioned above (14). The significance level (asymptotic) was α≤0.05 for all cases.

Results

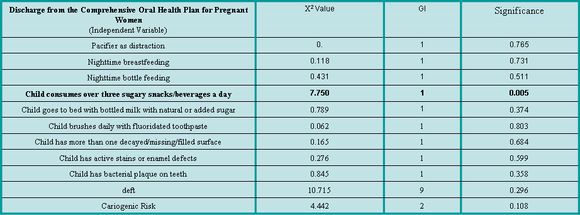

Table 1 shows the results for correlation between the independent variable “Discharge from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women” and the dependent variables under study. Out of all the dependent variables analyzed, “Child who consumes over three sugary snacks/beverages a day” proved to be highly significant (p<0.005); which implies that there is a correlation between the above mentioned variables. In particular, it was observed that the subjects who showed a positive response to the dependent variable had not been discharged from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women.

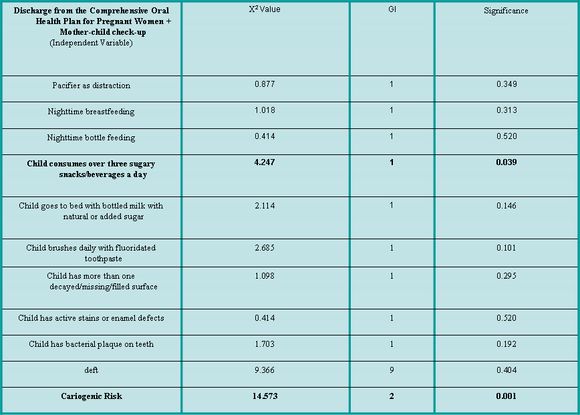

Table 2 shows the results for the correlation between the independent variable “mother child check-up” and the dependent variables under study. Out of all the dependent variables analyzed, “Child who consumes over three sugary snacks/beverages a day” (p<0.05) and the variable “cariogenic risk”(p<0.005) are associated with the variable “Mother-child check-up”, which implies that there is a correlation between the above mentioned variables. In particular, it was observed that the subjects who responded positively to the variable “Child who consumes over three sugary snacks/beverages a day” are associated to a lack of mother-child check-up and “low cariogenic risk” is associated to the presence of “mother-child check-up”.

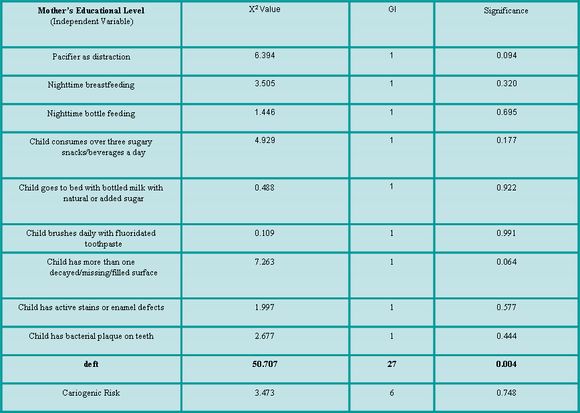

Table 3 shows the results for the correlation between the independent variable “Mother’s educational level” and the dependent variables under study. Out of all the dependent variables analyzed, the “deft” variable was found to be associated to the independent variable (p<0.005); this implies that there is a correlation between the variables under study. In particular, it was observed that, as deft increases, the educational level of the mother decreases.

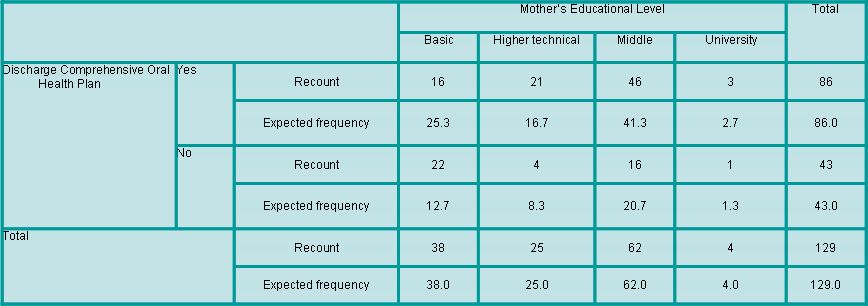

Table 4 shows the results for the correlation between the variables “Discharge from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women” and “Mother’s educational level”. The test was highly significant (p<0.005), which shows a clear link between a lower educational level and fewer number of discharges from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women.

Table 1. Correlation between the variable “Discharge from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women” and the dependent variables.

Table 2. Correlation between the variable “Discharge from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women + Mother-child check-up” and the dependent variables.

Table 3. Correlation between the variable “Mother’s educational level” and the dependent variables.

Table 4. Contingency table of the variables “Discharge from the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan” and “Mother’s educational level”

Finally, there was no correlation (p>0.05) for the independent variables “FONASA” and “Number of children” in any of the results between the independent and dependent variables under study.

Out of the total sample of children studied, based on the deft indicator, 30% show a record of dental caries. Within this percentage, the damage caused by caries to temporary teeth was observed to be 1.07 ± 2.24. The estimated average of the indicator is solely based on the “caries” component. Regarding white spots, it was observed that 58.9% of children had caries. After analyzing the total sample, it was observed that 88% present a high cariogenic risk, 7% moderate risk, and 5% low risk.

Discussion

The results of this study show that the educational components of the plan implemented did not achieve the expected outcomes in 2-year-olds at CESFAM in Lo Barnechea. According to AAPD guidelines, in addition to educating parents on their children’s oral health, dental check ups for children should begin when the first tooth appears and no later than 12 months of age (20-22). The main aim of early dental care is to monitor the development of dentition and occlusion, and therefore to be able to quickly detect and manage any problems that may arise (23). The time between dental check-ups should normally be 6 months, although this may vary depending on the individual needs of each patient (24-27). The risk of developing a certain disease should be assessed in each visit, since habits can change very quickly during childhood (18, 28). This dental care methodology enables us to constantly reevaluate and reinforce prevention oriented activities, which among other things, contributes to improving parents’ knowledge on the matter (29). A long-term study (30) was carried out in Germany, where they examined, educated and treated, if necessary, women and their children from pregnancy until the child’s third birthday every six months, and every 12 months until the child’s sixth birthday. When they were assessed at age 13 to 14, a significant reduction in caries incidence and severity was found, compared to the control group, which was formed by a group of randomly chosen adolescents of the same age. It was observed that, within the group under study, 89.7% did not have caries, with an average DMFT of 0.55 ± 1.0 and, within the control group, only 56.7% had no caries, with a DMFT of 1.5 ± 1.5 (p <0.05). In Chile, Gómez et al. (31) studied the effectiveness of a prevention plan targeting mothers and children since the fourth month of pregnancy until the child’s sixth birthday, with monitoring conducted every six months. At ten years of age, 70% of the children who had participated in the prevention plan were caries-free, while only 33% of the children in the control group were caries-free. The average DMFT of the children under study was 0.51 ± 0.93 and 1.57 ± 1.38 for the control group. This proves, just as Meyer et al. did, the effectiveness of an educational and prevention plan that targets mothers and children from pregnancy and with check-ups every six months: it not only reduces the incidence and severity of decay, but the benefits can also be observed six years after the plan was completed.

Chile’s current public health system ensures comprehensive dental care for pregnant women, which aims to, among other things, provide the child with a favorable environment for his/her oral health. Furthermore, the child’s first mandatory dental check-up is at the age of two and then at four for preschoolers. At this point the dentist will implement treatment, educational and prevention measures, depending on the dental resources available to the municipality (15). The lack of correlation between the variables under study could be explained by the fact that the current prevention and educational plan is only implemented at the prenatal stage, and a period of two years goes by from implementation to assessment. During this time, there is no reinforcement of the education, prevention and motivation needed to maintain healthy dental habits, which would in turn, improve preschoolers’ oral health. Probably, the high caries incidence and deft index increase among the population of 2-year-olds compared to the study conducted in the Metropolitan Region in the year 2007 (32) can be explained due to a lack of monitoring by a dental care professional. Furthermore, 88% of the sample has a high cariogenic risk level, which shows a strong likelihood of future caries damage. To achieve results that are similar to those of Meyer et al. and Gómez et al., there should be an oral health policy in place that implemented monitoring every 6 or 12 months.

It is worth noting the correlation between a low cariogenic risk and mother-child check-ups, which reinforces the importance of the information provided during pregnancy to reduce caries incidence in preschool children (30-34). The Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women does not cover the mother-child check-up, therefore it is not universal, since it is not publicly funded, but rather implemented at CESFAM in Lo Barnechea with the municipality´s own financial resources, which are higher than the average available to other municipalities.

Among the positive features of the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women, we can mention the correlation with the variable “child consumes over three sugary snacks/beverages a day”, since the educational measures implemented as part of the program allowed for a healthier diet with lower cariogenic level compared to that of children whose mothers did not participate in the plan. This would help reduce the damage caused by cariogenic bacteria. However, this variable alone is insufficient to have an impact on the child´s overall cariogenic risk.

The results obtained have limitations: a) they can be biased as the sample is not random. Children whose mothers attended CESFAM voluntarily were studied; b) the work was done in the Municipality of Lo Barnechea and it is not possible to generalize these results to all the services implementing the oral health plan; c) please note that, just as in any other survey, participants may have felt compelled to provide socially acceptable answers (35, 36), and d) the fact that daily sugar consumption was obtained by means of a questionnaire rather than a food diary could have led respondents to omit some hidden sources of sugar (37).

In order to reduce the prevalence of poor dental habits, cariogenic risk level and caries incidence, the educational and prevention measures delivered to the population should be reinforced and reformulated so as to have a greater impact on pregnant women and thus positively affect their children’s oral health. An updated epidemiological study of Chile’s preschool population and household dental habits would help strengthen the efforts to promote oral health.

Conclusions

1.The Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women and the mother-child check up implemented at CESFAM in the Municipality of Lo Barnechea, have not been able to reduce the incidence of poor dental habits nor the deft index in 2-year-olds, compared to those children whose mothers did not participate in the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women.

2.Children with low cariogenic risk are mainly those whose mothers attended the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women and the mother-child check-up (p<0.005).

3.The measures implemented in the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women (p<0.005) and the mother-child check-up (p<0.05) favor a less cariogenic diet on their children at 2 years of age.

4.The mother’s low educational level has a highly significant correlation (p<0.005) with a lack of compliance with the dental treatment during pregnancy and with a higher deft index in their children at 2 years of age (p<0.005).

5.No significant differences between the groups were found in most of the variables studied. This proves that the Comprehensive Oral Health Plan for Pregnant Women implemented at CESFAM in Lo Barnechea, Chile, does not achieve the expected outcome regarding an improvement of the children’s oral health at 2 years of age.

References

1. Alsada L, Sigal M, Limeback H, Fiege J, Kulkarni G. Development and Testing of an Audio-Visual Aid for Improving Infant Oral Health Through Primary Caregiver Education. J Can Dent Assoc [Internet]. 2005 [Cited: 2014 Aug 10];71(4):241- 241h. Available from: http://www.cda-adc.ca/JADC/vol-71/issue-4/241.pdf

2. Bahri N, Reza H, Bahri N, Sajjadi M, Boloochi T. Effects of Oral and Dental Health Education Program on Knowledge, Attitude and Short-time Practice of Pregnant Woman (Mashhad-Iran). J Mash Dent Sch. 2012; 36(1):1-12.

3. Cárdenas L, Ross D. Effects of Oral Health Education Program for Pregnant Woman. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2010; 90(2): 23-26.

4. Petrovic M. Evaluación del Programa de Educación para la Salud en el Tratamiento Estomatológico de Mujeres Embarazadas en la Ciudad de Nis-Serbia. Rev. ADM. 2007; 64(5): 197-200.

5. Agarwal V, Nagarajappa R, Keshavappa SB, Lingesha RT. Association of maternal risk factors with early childhood caries in schoolchildren of Moradabad, India. Int. J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21(5):382-8.

6. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Perinatal Oral Health Care. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry [Internet]. 2011 [Cite: 2014 May 07]. Available from:

http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_PerinatalOralHealthCare.pdf

7. Boggess KA, Edelstein BL. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern. Child Health J. 2006; 10(5 suppl):S169-174.

8. Cogulu D, Ersin NK, Uzel A, Eronat N, Aksit S. A long-term effect of caries-related factors in initially caries-free children. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2008; 18(5):361-7.

9. Douglass JM, Li Y, Tinanoff N. Association of mutans streptococci between caregivers and their children. Pediatr Dent. 2008; 30(5):375-87.

10. Kishi M, Abe A, Kishi K, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Kimura S, Yonemitsu M. Relationship of quantitative salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and S. sobrinus in mothers to caries status and colonization of mutans streptococci in plaque in their 2.5-year-old children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2009; 37(3):241-9.

11. Okada M, Kawamura M, Kaihara Y, Matsuzaki Y, Kuwahara S, Ishidori H, et al. Influence of parents’ oral health behaviour on oral health status of their school children: an exploratory study employing a causal modelling technique. Int. J Paediatr Dent. 2002; 12(2):101-8.

12. Zanata RL, Navarro MF, Pereira JC, Franco EB, Lauris JRP, Barbosa SH. Effect of caries preventive measures directed to expectant mothers on caries experience in their children. Braz Dent J. 2003; 14(2):75-81.

13. Ministerio de Salud. Aprueba garantías explícitas en salud del Régimen general de garantías en salud [Internet]. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de Salud; 2013 [Cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from:

http://www.minsal.gob.cl/portal/url/item/d692c627c623b9cae040010164016563.pdf

14. Díaz V. Metodología de la Investigación Científica y Bioestadística para Profesionales y Estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud. 2nd ed. Santiago: RIL Editores; 2009.

15. Chile. Ministerio de Salud. Pautas de Evaluación Bucodental. [Internet]. 2007 [Cited: 2014 Sep 05]. 2nd ed. Available from: http://200.54.170.197/estadisticas2006/monitoreo2009/PautasdeEvaluacionBucodentaria.pdf

16. World Health Organization. Encuestas de Salud Bucodental. Métodos Básicos. Geneva. [Internet]. 1997 [Cited: 2014 Sep 05]. 4th ed. Available from:

http://web.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/7dc33df0bb36ec58e04001011e011c36.pdf

17. Chile. Ministerio de Salud. Normas en la Prevención e Intercepción de Anomalías Dentomaxilares. [Internet]. 1998 [Cited: 2014 Sep 05]. Available from: http://web.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/7f2dd0d1a803c658e04001011e010fe2.pdf

18. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Caries Risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Reference Manual. [Internet] 2013-2014: [Cited: 2014 Apr 6];35 (6). Available from: http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf

19. Chile. Ministerio de Salud [Internet]. Chile: Superintendencia de Salud Gobierno de Chile; 2013 [Cited: 2014 Jul 7]. Available from: http://www.supersalud.gob.cl/consultas/570/w3-propertyvalue-4008.html

20. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the dental home. Pediatr Dent. 2012; 34:24-5.

21. American Academy of Pediatrics. Oral health risk as¬sessment timing and establishment of

the dental home. Pediatr [Internet] 2009 [Cited: 2014 Sep 5];124(2):845. Available from:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/5/1113.full

22. Berg JH, Stapleton FB. Physician and dentist: New initiatives to jointly mitigate early childhood oral disease. Clin Pediatr 2012:51(6):531-7.

23. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on management of the developing dentition and occlu¬sion in pediatric dentistry. [Internet] 2014 [Cited: 2014 Sep 5]; (official but unformatted). Available from: http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_DevelopDentition.pdf

24. Pienihakkinen K, Jokela J, Alanen P. Risk-based early prevention in comparison with routine prevention of dental caries: A 7-year follow-up of a controlled clinical trial; clinical and economic results. BMC Oral Health. 2005; 5(2):1-5.

25. Beil HA, Rozier RG. Primary health care providers’ advice for a dental checkup and dental use in children. Pediatr.2010;126(2):435-41.

26. Patel S, Bay C, Glick M. A systematic review of dental recall intervals and incidence of dental caries [abstract]. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010; 141(5):527-39.

27. Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Stearns SC, Quiñonez RB. Effectiveness of preventive dental treatments by physicians for young Medicaid enrollees. Pediatr. 2011; 127(3):682-9.

28. Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crystal YO, Ng MW, Crall JJ, Feath¬erstone JBD. Pediatric dental care: Prevention and management protocols based on caries risk assessment. CDAJ. 2010; 38(10):746-61.

29. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent. 2011; 35(6):175-87.

30. Meyer K, Geurtsen W, Günay H. An early oral health care program starting during pregnancy: results of a prospective clinical long-term study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2010; 14(3):257-64.

31. Gomez SS, Emilson C-G, Weber AA, Uribe S. Prolonged effect of a mother-child caries preventive program on dental caries in the permanent 1st molars in 9 to 10-year-old children. Acta Odontol Scand. 2007; 65(5):271-4.

32. Ceballos M, Acevedo C. Diagnóstico en Salud Bucal de niños de 2 y 4 años que asisten a la educación preescolar [Internet]. Región Metropolitana: MINSAL; 2007 [Cited 2014 Apr 6]. Available from: http://web.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/7dc33df0bb34ec58e04001011e011c36.pdf

33. Mohebbi S, Virtanen J, Vehkalahti M. Improvements in the Behaviour of Mother- Child Pairs Following Low-cost Oral Health Education. Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry. 2014; 12(1): 13-19.

34. Sundell A, Ullbro C, Koch G. Evaluation of preventive programs in high caries active preschool children [Abstract]. Swed Dent J. 2013; 37(1): 23-30.

35. Kissinger P, Rice J, Farley T, Trim S, Jewitt K, Martin DH. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behaviour research. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:950–4.

36. Sjöström O. Holst D. Validity of a questionnaire survey: response patterns in different subgroups and the effect of social desirability. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002; 60:136-14

Annex

1

Date........

Clinical Record

Patient..............................................................................................................

Social Security number.............................................

DOB................................................................

Age......years....months. Child

number.................................

Name

Mother......................................................................

Mother’s

Social Security number............................

Contact telephone

number........................................................................

Family

information

Occupation

Mother.......................................................................

Father..........................................................................

School/daycare............................................................

Address........................................................................................................................................................

Mother’s

educational level. Basic: 1 Middle: 2 Higher

technical: 3 University: 4

Fonasa Range A B C D

Mother was part of the

comprehensive oral health plan for pregnant women and was discharged. Yes:

1 /

no: 2

Mother attended her

mother-child check-up. Yes: 1 /

no:2

Number of children primipara: 1 2- 3 children: 2 4+: 3

Presence

of poor oral habits

|

Poor

habit |

Yes:

1 No: 2 |

|

Pacifier as distraction |

|

|

Nighttime breastfeeding |

|

|

Nighttime bottle feeding |

|

deft

index

Decayed……….. Filled.........

Extraction indication........teeth.......deft:

Caries

Risk Assessment Form for children aged 0-5

|

Factors |

High

Risk |

Moderate

Risk |

Low

Risk |

|

Biological |

|

|

|

|

Mother/primary caregiver

with active caries |

Yes |

|

|

|

Parents/caregiver of low

socioeconomic status |

Yes |

|

|

|

Child consumes over three

sugary snacks/beverages a day |

Yes |

|

|

|

Child goes to bed with

bottled milk with natural or added sugar |

Yes |

|

|

|

Child needs special

medical care |

|

Yes |

|

|

Child is a newly arrived

immigrant |

|

Yes |

|

|

Protectors |

|

|

|

|

Child is given optimally

fluoridated water or fluoride supplements |

|

|

Yes |

|

Child brushes daily with

fluoridated toothpaste |

|

|

Yes |

|

Child is given topical

fluoride administered by a professional |

|

|

Yes |

|

Child undergoes regular

and close dental care provided by a professional |

|

|

Yes |

|

Clinical

evaluation |

|

|

|

|

Child has more than 1

decayed/missing/filled surface |

Yes |

|

|

|

Child has white active

stains or enamel defects |

Yes |

|

|

|

Child has high S. Mutans

levels |

Yes |

|

|

|

Child has bacterial plaque

on teeth |

|

Yes |

|

|

Cariogenic risk assessment |

High:

1 |

Moderate:

2 |

Low:

3 |

2.Bahri N, Reza H, Bahri N, Sajjadi M, Boloochi T. Effects of Oral and Dental Health Education Program on Knowledge, Attitude al Short-time Practice of Pregnant Woman (Mashhad- Iran). J Mash Dent Sch. 2012; 36(1):1-12.

3.Cárdenas L, Ross D. Effects of Oral Health Education Program for Pregnant Woman. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2010; 90(2): 23-26.

4.Petrovic M. Evaluación del Programa de Educación para la Salud en el Tratamiento Estomatológico de Mujeres Embarazadas en la Ciudad de Nis- Serbia. Rev. ADM. 2007; 64(5): 197-200.

5.Agarwal V, Nagarajappa R, Keshavappa SB, Lingesha RT. Association of maternal risk factors with early childhood caries in schoolchildren of Moradabad, India. Int. J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21(5):382-8.

6.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Perinatal Oral Health Care. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry [En línea]. 2011 [citado 07 May 2014]. Disponible en:

http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_PerinatalOralHealthCare.pdf

7.Boggess KA, Edelstein BL. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern. Child Health J. 2006; 10(5 Suppl):S169-174.

8.Cogulu D, Ersin NK, Uzel A, Eronat N, Aksit S. A long-term effect of caries-related factors in initially caries-free children. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2008; 18(5):361-7.

9.Douglass JM, Li Y, Tinanoff N. Association of mutans streptococci between caregivers and their children. Pediatr Dent. 2008; 30(5):375-87.

10.Kishi M, Abe A, Kishi K, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Kimura S, Yonemitsu M. Relationship of quantitative salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and S. sobrinus in mothers to caries status and colonization of mutans streptococci in plaque in their 2.5-year-old children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2009; 37(3):241-9.

11.Okada M, Kawamura M, Kaihara Y, Matsuzaki Y, Kuwahara S, Ishidori H, et al. Influence of parents’ oral health behaviour on oral health status of their school children: an exploratory study employing a causal modelling technique. Int. J Paediatr Dent. 2002; 12(2):101-8.

12.Zanata RL, Navarro MF, Pereira JC, Franco EB, Lauris JRP, Barbosa SH. Effect of caries preventive measures directed to expectant mothers on caries experience in their children. Braz Dent J. 2003; 14(2):75-81.

13.Ministerio de Salud. Aprueba garantías explícitas en salud del Régimen general de garantías en salud [En línea]. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de Salud; 2013 [citado 10 abril 2014]. Disponible en:

http://www.minsal.gob.cl/portal/url/item/d692c627c623b9cae040010164016563.pdf

14.Díaz V. Metodología de la Investigación Científica y Bioestadística para Profesionales y Estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud. 2ª ed. Santiago: RIL Editores; 2009.

15.Ministerio de Salud Gobierno de Chile. Pautas de Evaluación Bucodental. [En línea]. 2007 [citado 05 septiembre 2014]. 2° edición. Disponible en: http://200.54.170.197/estadisticas2006/monitoreo2009/PautasdeEvaluacionBucodentaria.pdf

16.Organización Mundial de la Salud. Encuestas de Salud Bucodental. Métodos Básicos. Ginebra. [en línea]. 1997 [citado 05 septiembre 2014]; Cuarta Edición. Disponible en:

http://web.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/7dc33df0bb36ec58e04001011e011c36.pdf

17.Ministerio de Salud gobierno de Chile. Normas en la Prevención e Intercepción de Anomalías Dentomaxilares. [En línea]. 1998 [citado 05 septiembre 2014]. Disponible en: http://web.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/7f2dd0d1a803c658e04001011e010fe2.pdf

18.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Caries Risk Assessment and Managment for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Reference Manual. [En línea] 2013- 2014 [citado 6 abril 2014];35 (6). Disponible en:

http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf

19.Chile. Ministerio de Salud [En línea]. Superintendencia de Salud Gobierno de Chile; 2013 [citado 7 julio 2014]. Disponible en:

http://www.supersalud.gob.cl/consultas/570/w3-propertyvalue-4008.html

20.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the dental home. Pediatr Dent. 2012; 34:24-5.

21.American Academy of Pediatrics. Oral health risk as¬sessment timing and establishment of

the dental home. Pediatr [en línea] 2009 [citado 05 septiembre 2014];124(2):845. Disponible en:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/5/1113.full

22.Berg JH, Stapleton FB. Physician and dentist: New initi-atives to jointly mitigate early childhood oral disease. Clin Pediatr 2012:51(6):531-7.

23.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on management of the developing dentition and occlu¬sion in pediatric dentistry. [en línea] 2014 [citado 05 septiembre 2014]; (official but unformatted). Disponible en:

http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_DevelopDentition.pdf

24.Pienihakkinen K, Jokela J, Alanen P. Risk-based early prevention in comparison with routine prevention of dental caries: A 7-year follow-up of a controlled clinical trial; clinical and economic results. BMC Oral Health. 2005; 5(2):1-5.

25.Beil HA, Rozier RG. Primary health care providers’ advice for a dental checkup and dental use in children. Pediatr.2010;126(2):435-41.

26.Patel S, Bay C, Glick M. A systematic review of dental recall intervals and incidence of dental caries [abstract]. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010; 141(5):527-39.

27.Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Stearns SC, Quiñonez RB. Effectiveness of preventive dental treatments by physicians for young Medicaid enrollees. Pediatr. 2011; 127(3):682-9.

28.Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crystal YO, Ng MW, Crall JJ, Feath¬erstone JBD. Pediatric dental care: Prevention and man-agement protocols based on caries risk assessment. CDAJ. 2010; 38(10):746-61.

29.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent. 2011; 35(6):175-87.

30.Meyer K, Geurtsen W, Günay H. An early oral health care program starting during pregnancy: results of a prospective clinical long-term study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2010; 14(3):257-64.

31.Gomez SS, Emilson C-G, Weber AA, Uribe S. Prolonged effect of a mother-child caries preventive program on dental caries in the permanent 1st molars in 9 to 10-year-old children. Acta Odontol Scand. 2007; 65(5):271-4.

32.Ceballos M, Acevedo C. Diagnóstico en Salud Bucal de niños de 2 y 4 años que asisten a la educación preescolar [en línea]. Región Metropolitana: MINSAL; 2007 [citado 6 abril 2014]. Disponible en:

http://web.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/7dc33df0bb34ec58e04001011e011c36.pdf

text in

text in