Introduction. What are virtual communities?

Living in a reality mediated by digital technologies allows us - and, at the same time, pushes us - to learn beyond the contexts in which we place ourselves. More and more, it is asked that all generations be able to learn, not only life-long but also life-wide (Banks, Au et al, 2007), not only in our school, university or workplace, but also through informal and non-formal education institutions, at home, on the streets or in virtual spaces.

Since the Internet began, there have been academic discussions in many fields about how computer mediated communication (CMC) might influence the lives of individuals, interpersonal relationships between people, and the social institutions that emerge from human relationships (Rheingold, 2000). A term that has been broadly used to approach online social interactions has been virtual community. However, this is a controversial term, since it has generated debate around the tensions between the promises and limitations of cyberculture, the relationship between online and ‘real’ life, and the notion of community itself (Bell, 2001).

The term ‘virtual community’ was used by Rheingold (1993) to describe the webs of personal relationships in cyberspace. Later, it was defined as a group of individuals with shared interests that regularly gather to discuss the subject of interest shared by its members through online platforms (Figallo, 1998).

These virtual communities, made up mostly of young people, besides being communities of interest, are learning and knowledge-creation communities, although not in the academic sense of these terms. That is, it is not about educational communities with pre-established teaching objectives and static characteristics and roles that establish what to learn and those who teach or learn, as is defined by Sacristán (2013). On the contrary, the simple fact of sharing information and diverse practices generates certain learning in the participants. These communities are becoming the way to learn par excellence, in particular among the people of the age group indicated above.

Furthermore, virtual learning communities incorporate many of the characteristics of the discourse communities, practice and knowledge construction (Montes de Oca, García & Fuster, 2011). These common elements make it difficult to draw a definitive dividing line between the different types of communities, as well as to determine when a virtual community (created for other types of functions) promotes practices that contribute to the members’ learning. In fact, people often use social networks both to satisfy emotional needs or socialize and to produce knowledge and learn. However, in the virtual-learning, practice and knowledge communities, the idea of learning as a social construction is highlighted (Gros, 2008). That is, from some knowledge, skills or attitudes that come mainly from the intensive interaction between people (Bosco, Miño, Rivera-Vargas, Alonso, 2016).

In different forms of online social networks, several of their members have never met face-to-face, but they feel they belong to a group of people with similar interests and characteristics. Likewise, that lack of physical experience does not affect the possibility of sharing common interests that enable the development of social capital, such as: arts, culture, activism, and politics. One of the collectives that make use of online social networks is young people. According to the study Digital Youth, most youngsters in their middle-school and high-school years use online networks to extend their friendships and some use them to explore their interests and find information to which they have no access to at their local community (Ito et al, 2008).

It should be noted, however, that many social networking services can host virtual communities, since they bring together people linked by common interests that remain linked and involved for a long period, as they use the Internet as a new anthropological space where they share knowledge and learn (Henri and Pudelko, 2003).

Virtual communities, although not a novel concept, refer to an online environment where some people find a place to socialize in a different or complementary way of what they find in face-to-face interaction (Rheingold, 2000). In order to differentiate virtual communities from other forms of online social networks, we use the notion of community as a social space created and maintained by people who have the necessity or the desire of a safe shared space. In theorizing about community, we develop Hobsbawm’s conception of communitarianism that has to do with the necessity shared by people to create a safe refuge, since “men and women look for groups to which they can belong, certainly and forever, in a world in which all else is moving and shifting, in which nothing else is certain” (1996, p. 40). Zygmunt Bauman (2000) also considered that communitarianism is attractive when everything feels uncertain. In Liquid Modernity, he related the idea of belonging to a community with the promise of finding a safe refuge and the heat of shared identity.

In this paper, we are presenting some results of the research project “Youth Virtual Communities: making visible their learning and their knowledge”, funded by the Reina Sofía Centre of Adolescence and Youth (Call 2015). In this research, we have sought to explore how and what young people learn in virtual communities in order to show the potential of such communities in the process of learning and identity-building of 15 to 29-year-old Spaniards. Our study has paid attention to communities of interest (Sacristan, 2013), with the hypothesis that sharing an interest encourages young people to learn and build knowledge, but not in an academic sense.

In the results section, we first present the characteristics of the virtual communities that have been researched, building from the final report of the project, which has been published recently (see Alonso, et al., 2016). On the second part, we extend the discussion, by analyzing further the relationship between the ways young people learn through virtual communities and social participation. Through this analysis we aim to answer the following two questions: (i) Which reasons lead young people to participate in virtual communities?; and (ii) how is learning and social participation promoted through virtual communities?

Methodological proposal

In order to approach this phenomenon that takes place in multiple spaces, we conducted seven case studies based on virtual (Hine, 2004, 2005) and multi-sited (Falzon, 2009) ethnography. This methodological approach allowed us to follow connections, interactions, trajectories and tensions between time and space and to pay attention to the implications the Internet has in the organization of social relationships, communication, authorship, and privacy. Therefore, we understood communities not as isolated places, but as spaces created by connections, realizing that we needed to cross constantly the border - if there is one, that is - between physical and virtual spaces which are constantly intertwined (Falzon, 2009).

The research process had two main stages: (1) the detection and mapping of 23 virtual communities with a high participation of Spanish youth between 15 and 29 years of age, and (2) the implementation of case studies in seven virtual communities.

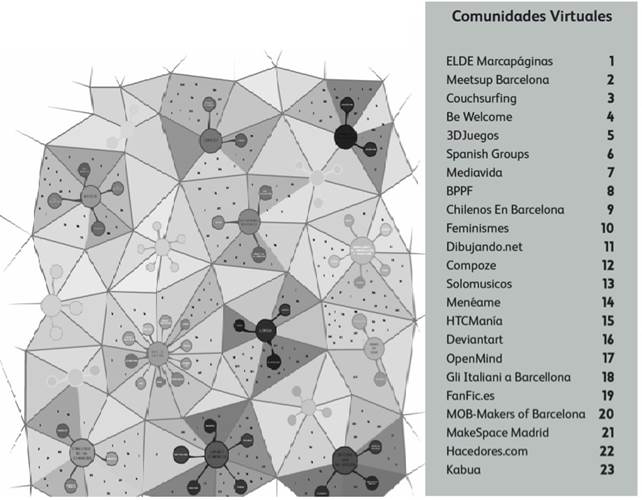

The first exploration allowed us to create a cartography - Figure 1 - of the 23 communities, from the categories that emerged by the saturation of the observations made at each community. To choose the sample, we started from previous research projects with young people, our experiences in communities and the relationships we had with youngsters who were involved and linked to these spaces by interest or need.

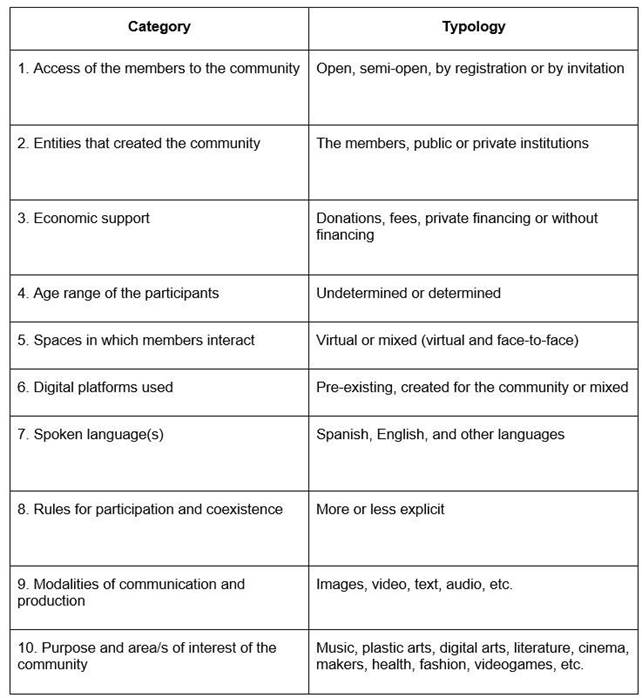

The categorization system we developed for the analysis emerged in an inductive form. As it can be seen in Table 1, we created ten categories or axes that allowed us to order the great diversity of communities. We took into account aspects such as the main topics or interests of the community, the open/close nature of access, the entities who created the community, their financial sources, the ages of the participants, the virtual and face-to-face spaces where they met, the languages spoken, the rules of participation and the modalities of communication.

In the second phase of the project, we conducted case studies in seven virtual communities we chose from the first sample. In order to choose seven cases that would be rich in terms of data and different among them, we selected communities with high participation of young people aged between 15 and 29 years old. We also chose communities that were related with arts, culture, the maker movement and activism or social change.

The communities identified for the study were (1) Devianart, (2) The Book of the Writer, (3) Dibujando.net, (4) Cosplay Spain, (5) Kabua, (6) Openmind, and (7) Feminisms. We negotiated with the administrators of the communities and sent them ethics documents, in order to conduct face-to-face or virtual interviews with 2-3 members of the community and virtual observations of the virtual environment they used to interact. We also informed the members of the community of our participation, asking for volunteers and informing that we would guarantee the confidentiality of the informants.

Below are the descriptions of the virtual communities in which the case studies were conducted. The thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) we implemented was based on the categorization made in the first phase of the research, with the interest of highlighting the most relevant aspects of virtual communities as spaces that: (a) question the liberal social order, (b) make visible the participation of young people and (c) vindicate and promote social, economic and production, educational or cultural changes.

Description of the virtual communities

Dibujando

Dibujando is defined as a "social platform of artists who wish to show their artworks to the world" and where others can discover the creativity and talent housed in it. It was created in 1999 in Valencia with the purpose of providing artistic knowledge to the Spanish-speaking community and therefore its creators had didactic purposes from the beginning. It has 20,000 users who share an interest in drawing, and although we cannot determine the age range, a good part of the participants is between 15 and 29 years old. Even so, it is important to note that approximately 400 of the members participate in an active way through the website.

The website the members of this community use to interact and show their artworks was created specially with this purpose. It has three main environments in which learning is promoted: The Gallery, The Tutorials and The Community. The dynamics and possibilities that are generated in these spaces are: the participation in drawing contests, communication through discussion forums and the contribution and access to image galleries.

Feminismes

Feminismes is a group of Spanish origin that was created through the social network service Facebook, where "the ideas, information and activism about feminism are shared, discussed and exchanged, mostly in Spanish" (Description of the Feminismes group). In the description, it is specified that any kind of feminism is welcome, since they consider that there is not only one type of it, and that the constructive exchange is always enriching. At present, it has 2951 members and six administrators. Its access is closed, which means that users who want to access the content and interact with its members, need to receive an invitation and be accepted by one of the administrators.

All kinds of people are welcome to the group, as long as they take into account the following participation rules: (1) sexist ideas and attitudes are not allowed, (2) every idea and every person has to be respected, (3) insults are not accepted, (4) people who do not consider themselves feminist can participate only if they express their ideas with respect and they do not question the existence of feminism and (4) heterosexual men are invited to be part of the community, only if they do not abuse of their power by constantly posting messages to the group. Their administrators are presented as those in charge of moderating and ensuring the safety of the group. To do this, they offer members the possibility to address them if they feel they are not being treated with respect.

OpenMind

OpenMind is a virtual community aimed at all people who want to participate and share their reflections around a series of areas of knowledge. It was created by the BBVA bank in order to generate and spread knowledge through books, articles, posts, reports, infographics, and videos. The community is based on the idea of generating "a point of encounter and space for the dissemination of present and future knowledge" (Section 'What is OpenMind. Rules of etiquette').

The differentiation and hierarchization of roles among the participants of this community is more evident than in the other communities since there are administrators, authors, collaborators and participants defined by institutional criteria. Three people are dedicated to the administration of the community through the areas of strategy and dissemination, social relations and knowledge management. Secondly, the authors are usually internationally recognized people who write essays or academic articles in the book that is published annually in both physical and digital format. These authors are contacted by the administrators to be part of the publication, which has previously defined themes. Finally, the collaborators are researchers, master’s degree holders or doctoral students, people related to the company, institutions and individuals who are active in the network and are interested in scientific dissemination. These can be contacted by the administrators, but they can also request their participation as collaborators.

El Libro del Escritor

El Libro del Escritor is defined as a community of writers, professionals, and amateurs. It was created in 2014 by two young people with the intention of creating multi-platform software oriented to writers that could be used from different mobile devices. In order to make the space known, the creators of the community developed a blog where every week they published texts related to writing and offered short training courses and other services.

At this moment, the community is organized in groups by regions of the Spanish State, and although the platform that is most used is Facebook, they have also created the website "Gamified literary social network". The founders organized a crowdfunding with the purpose of remunerating the work of the developer of the website and the organizer of the community activities. The range of profiles and ages of the participants is very wide, since both professional writers and amateurs, young people and adults participate.

Kabua

Kabua was created by the UNESCO Center of Catalonia in 2008 with a budget item in collaboration with the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and TV3. Their main interest was to create a platform for young people between 12 and 18 years old to promote values related to social transformation using digital technologies. The website specifies that the initiative seeks to “help young people enhance their empowerment as transforming agents of reality" (Kabua website).

It is an open site in which any young person can participate in forum spaces, gallery, visual resources and guides in relation to their topics of interest. There are also links to the Facebook and Twitter accounts of the community. There are rules of coexistence that ensure mutual respect in exchanges between participants. Although the web space is organized in a similar way to the rest of the virtual communities of the study, online participation of young people takes place much more in social networks, so the web space became a consultation tool.

Cosplay (Spain)

This community was created in 2010 with the intention of creating a meeting point and a way to publicize the Cosplay1. As indicated on the website, members consider that Cosplay "apart from being a hobby and fun, is also an art form". Therefore, the purpose of the community is to encourage people who share an interest in cosplay to share their experience and publicize.

Creating the community was not easy for its two founders, but little by little, experienced cosplayers and also amateurs with a desire to learn began to participate. Cosplay has a website with 999 registered members, a Facebook page and a space on Twitter. Most of the interaction happens in the Forum of the web, where they have a moderator that promotes respect and constructive criticism.

DeviantArt

This is one of the largest virtual communities on art that can be found on the Internet, since it is made up of 35 million users from all over the world. Most of these are from the United States and the main language is English, but young people from Spain also participate in the website that houses it. It was founded in 2000 and, although its initial purpose was very limited, it quickly became the sharing of digital and traditional art. It is a semi-open community, so all registered people can access and upload content. Users can also be organized into groups with their own rules of participation, although they are subordinated to those of the community in general.

The founders allocated 15,000 Euros to maintain the service and it soon became a company that used financing methods such as advertising and even the possibility of creating Premium accounts that give advantages to participants who pay a fee. Although the main objective is to share productions, they also publish tutorials, contests, and face-to-face meetings. Some users even use the website as a personal and professional portfolio.

Discussion

From the information that we have obtained and analyzed during the execution of this research2, and considering other new focuses of interest that have emerged once we have finished the research, next, we will analyze the two questions that we have proposed in the introduction of this article: Which reasons move young people to participate in virtual communities?; and how is learning and social participation promoted through virtual communities?

A characterization of virtual communities

In relation to the configuration of virtual communities, we do not intend to define them from a technical point of view, but to broaden our understanding of the reasons that motivate young people to create virtual environments and use them to interact with people they have never met face to face. To start with, the members of the majority of the communities we have analyzed shared a sense of familiarity, comfort, emotional attachment or feeling at home, that has been theorized as a “sense of belonging” (Antonsich, 2010).

Secondly, although participation in virtual communities tends to be high beyond the age groups and gender or socioeconomic dimensions, many of these communities were created by young people and they were the most active users. The main reason that motivated them to feel they belong and participate in a virtual community was to exchange knowledge by interacting with others with whom they shared an interest. They described the communities as spaces to share, discuss and exchange ideas, information and activism, to show their artworks to the world, to spread knowledge, to promote values related with social transformation and to create a meeting point to share experiences and publicize ideas.

We also characterize them as multi-purpose spaces, because of two main reasons. On the one hand, the virtual environments used by its members had several sections, such as Community, Gallery and Contests. This means that not all members necessarily surfed all sections and some of them could be interested mainly in the discussions, while others would just consult the gallery. Consequently, not all participation in virtual communities was active, but in some cases, it was passive (Jenkins, 2014; Jenkins, Ito & Boyd, 2016). On the other hand, through the interviews we identified that individuals that were part of each community had different reasons to participate. For example, one member of Feminismes wanted to get answers to the discomfort she felt as a woman with some attitudes and situations in her everyday life. Another member wished to make a change in society through activism and another one considered the didactic potential of the community, by helping others to understand better what feminism is and to identify patriarchal values and practices.

Another common characteristic was that the participants used one or several virtual environments to interact, discuss and share or access ideas and productions. Nevertheless, only three of the communities interacted through a website that has been created specially to host the community. Another one used Facebook and the three remaining cases used both their website and social network services to communicate, such as Twitter or Facebook.

A clear level of differentiation among the communities is also significant. In the first place, some communities were constituted by no more than one thousand members, while others had up to 35 million users. More importantly, some communities were created by its members following their common interests, while in other cases, an institution with corporative interests and a budget induced their creation. Therefore, we question to which extent we can define any group of individuals who interact online with a common interest as a virtual community. It is necessary to differentiate between communities that are created by young people who share a common interest and want to share their ideas (from the bottom up) from institutions who wish to replicate this kind of community to meet their corporative goals (from top to bottom) (Miño, Rivera-Vargas & Salazar, 2017).

All the virtual communities we have analyzed shared another characteristic: the creation of a common set of norms of coexistence to ensure mutual respect in the exchanges between their members. They also used mechanisms to make the participants follow the rules, such as the figure of an administrator to moderate the discussions when a member became aggressive and disrespectful, a ‘closed’ feature of the website or the group to choose who could be part of it, and the possibility of expelling a member that broke the rules. Nevertheless, only the communities that were created by external institutions set the rules and mechanisms from the beginning and maintained them over time. In the communities created by its members, these rules and mechanisms emerged from specific moments and situations that made the participants feel they needed some kind of moderation or control.

Regardless of the size of the community or if it was created by young people or by an institution for young people, all the virtual communities we have analyzed were located in a bigger social context and had changed over time. They all emerged as a consequence of the phenomena that shape society and therefore, they were in permanent transformation and redefinition. However, some virtual communities were a big success among young people and they grew fast, while others failed to engage others and did not survive.

Learning, social participation and belonging

Virtual communities are built on social interactions, practices and relationships. Therefore, their success is not necessarily measured by the number of individuals that are part of it, but by the ability of their members to create social bonds and engage in online conversations or activities. In the interviews with the founding members, they recognized their lack of expectations towards the possibility that thousands of people would end up being part of it. This brings us to the questions: why do young people engage in virtual communities? Why should they spend so much time interacting with others online? And what benefits do they find?

As researchers on Sociology and Education, we find this phenomenon especially intriguing. Through this article we have explored the hypothesis that what makes young people engage in virtual communities is the sense of belonging to a group and the opportunities it gives them to learn. Building on the notion of situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), we identify that one vital aspect of virtual communities is that they feel part of it and because of this, their members are constantly creating opportunities to learn with and from each other.

An example from the case study dibujando.net is the collective learning process that emerged from a conversation in a Forum. Some members opened a discussion through their website to promote the creation of a magazine. Their idea was to bring together some of the best drawings and comics of their gallery, to create tutorials that teach others how to use graphic software and to make reviews of artists that could be of interest to the community. The user who made the proposal specified: “Everybody can participate without any kind of distinction. All contributions will be taken into account and don’t be afraid to make comments because almost everybody is new at this” (dibujando.net website). His message received hundreds of answers with questions, proposals, and contributions. For example, one user proposed to create a section with illustrated poems and tales for the fourth edition of the magazine.

Creating a magazine promoted learning in many different ways. Firstly, the majority of the participants who volunteered were not experts in the field and they encountered many difficulties in creating their comic stories, tutorials or author reviews. Participating in this activity was an opportunity to surf the web in search of how to do it, take a book from the library or ask an expert for help. Secondly, the volunteers had to collaborate with each other in order to achieve their goal, which involved many skills related with the processes of management and production. In the case of the volunteers who made the tutorials, when they made explicit how to use a tool, they were becoming aware of their knowledge and at the same time putting into practice their teaching skills. Finally, the volunteers used several tools to create, edit and publish the content of the magazine. Their discussions implied putting their competences into practice, broadening their knowledge and improving their social skills.

The members of the virtual communities created from the bottom up considered that being part of that community promoted learning about topics and through processes that not always had space (or place) in formal institutions (Alonso et al, 2016). As we can see in the last example, some activities promoted independent learning, collaboration, answer to questions that are discovered through the creative process, consulting experts and teaching and learning at the same time. Furthermore, learners were able to choose what to do, how to do it and with which tools; their contributions were related to their individual and collective interests and their experience might have helped them improve competences they needed in their present and future lives.

However, we also identified that virtual communities were not free of hierarchies, norms and internal power relations which could repeat the hierarchies and stratifications present in modern institutions. For example, in the case of Feminismes, the administrators took decisions on behalf of the rest of the members of the community, such as who was accepted or who should be expelled from the group, and therefore, they played a privileged position of power or influence. On the other hand, the majority of the members of this community have been young women who wanted to create a virtual safe space to discuss gender issues “without the risk of being physically harmed if you say something controversial”.

Therefore, this virtual community created its own politics of belonging (Antonsich, 2010) through structures of power, freedom and control, which at the same time were drivers that enabled or inhibited feelings, sense of belonging and identity (Miño, Rivera & Cobo, in press). In this regard, we question if virtual communities facilitate free expression and promote social inclusion or if they create fragmentation and exclusion by not accepting the presence of certain individuals who do not respect the rules.

Finally, we have been able to recognize that virtual communities with activist goals have the potential to become spaces for social participation, capable of harboring and promoting various ways of resisting the repression sometimes exerted by the social, political and cultural structure of modern societies. In these kinds of virtual communities, learning is associated with resistance and social demand, promoting and giving visibility to new attitudes, expectations, experiences and knowledge (Alonso et al, 2016).

Conclusions

Based on the main results of the project “Youth Virtual Communities: making visible their learning and their knowledge” and on the subsequent analysis that we have carried out, we have explored the questions: which reasons lead young people to participate in virtual communities?; and how is learning and social participation promoted through virtual communities? In this section, we summarize some of the main ideas that have been developed throughout the article.

In relation to the characterization of virtual communities and the reasons that lead young people to participate, we highlight the following:

- Firstly, the participants of virtual communities engage in them essentially to exchange knowledge interactively. In this sense, virtual communities are multi-purpose spaces legitimized by their most active participants.

- Secondly, although the profile of the participants tends to be beyond age groups, gender or socioeconomic dimensions, they are preferably created by young people, who are also the most active users.

- Thirdly, it is necessary to differentiate between communities that are created by young people who want to share their ideas from institutions who wish to replicate this kind of community to meet their corporate goals (from top to bottom, and young people that want to share a common interest as a vindictive act (from the bottom up), and). In this sense, virtual communities have the potential to become spaces for social participation, capable of harboring and promoting various ways of resisting the repression sometimes exerted by the social, political and cultural structure of modern societies.

In relation to the learning and social participation that are promoted among virtual communities, we find that:

- Firstly, the members of virtual communities recognize the constant and permanent learning opportunities they find and create. In addition, the activities promoted by their members might be opportunities for them to put their competences into practice, broaden their knowledge and improve their social skills.

- Secondly, we have noticed that many virtual communities are recognized as learning environments that have no space (or place) in formal institutions. In this sense, we recognized that the participants of these virtual communities do not follow established teaching goals, the roles of the participants are not static, and learning is understood as a social construction (Gros, 2008).

- Thirdly, in order to remain valid and to prevail over other similar spaces, virtual communities are hierarchized through norms and internal power relations, which can even repeat the hierarchies and stratifications present in modern societies. We have found that this action happens with the intention of transforming the virtual communities into a safe environment. In this way, it is possible to promote the free expression of their members and the possibility of generating transgressing speeches. Virtual communities facilitate free expression, and this can promote social inclusion, but at the same time they might create fragmentation and exclusion by not accepting the presence of certain individuals who do not respect their rules.

Finally, it should be noted that this type of environment can be transformed into important, non-formal learning spaces among its own participants. Being part of a virtual community is an opportunity for young people to explore their interests and satisfy their curiosity, deciding what they want to know and how they want to delve into it. This promotes their agency and poses an alternative to formal and structured educative contexts. Nevertheless, while it can be very rich in terms of learning, young people also need to be prepared to face the variety of information and perspectives they find when they surf the Internet.

At the same time, the active proliferation of new virtual communities shows us how important it is for our society to think about the new needs of inclusion and social participation that young people have in the present. Both through its creation and participation, in most virtual communities, young people are the main actors. In these spaces, young people seek new ways to build their identities in a society that increasingly considers and represents their lifestyles and concerns.