Worldwide, more than 10 million people are deprived of their freedom. Of these, 700,000 are women (Walmsley, 2016). Although female incarceration is considerably smaller than male imprisonment, it is noteworthy that, between 2000 and 2016, the number of female prisoners in the world increased by 50%. In the same period, the growth of the male prison population amounted to 20% (Walmsley, 2017). These data are a consequence of the hardening of laws and actions to combat drug trafficking, the crime that most imprisons women in the world (Anderson & Kavanaugh 2017; Reynolds, 2008).

It is noted that countries that have relaxed the legislation on drug trade and consumption, such as Portugal and Uruguay, have reduced female arrests while, in most of the nations in Latin America and Southeast Asia, incarceration of women continues to rise throughout the 21st century (Walmsley, 2017). Based on this reality, it can be affirmed that the rapid growth of the jail population is not necessarily a result of an actual increase in crime, but rather an increase in punishment (Cunha, 2014). In addition, the motives for crime, the types of crimes committed and the impact of incarceration are different for men and women (Cerneka, 2009; Moe & Ferraro, 2006).

In order to understand these different experiences in prisons, one should adopt a gender perspective, a concept that opposes the biological determinism of sexual differentiation and is based on social and relational aspects that go beyond normative definitions of femininity and masculinity. Gender is a social classification that overlaps with the idea of sexed bodies, since anatomical sex is not in itself a determining element of human behavior. The focus is on the analysis of sexual differences within social relations that are permeated by power relations. Asymmetries in the access or control of material and symbolic resources reveal the way gender is "implicated in the conception and construction of power itself" (Scott 1995a, p. 88).

In addition to class and to race, gender is a category that allows analysis of unequal power relations that are rooted in societies (Scott, 1995a). In this sense, by taking prison as a historical institution, we can include another dimension in this triad of intersections: punishment (Davis & Dent, 2003). In other words, given the asymmetries of power, it is crucial to recognize that the criminal sanctions applied to people are directly connected to gender, class and race markers.

On the other hand, when the deprivation of liberty is applied, these markers of difference among individuals tend to be erased. Angela Davis, who knows criminal systems on different continents, points out that despite distinctions between nations and regions, there are deep structural and operational similarities in prison units around the world, especially those intended for the confinement of women (Davis & Dent, 2003). Those who are different are punished similarly.

In general, prison population consists of poor and non-white people (Davis & Dent, 2003). In the case of women, it adds up to the fact that crime, more than mere violation of law, is socially understood as a violation of norms and expectations about female behavior. According to gender prescriptions, crime belongs to the public sphere, and therefore, to the space meant to be occupied by men. Women, when engaging in delinquent behavior, go beyond the private environment of home and act beyond the domestic, conjugal and/or maternal roles (Buglione, 2002). If crime is reserved for men, prisons are obviously built for them.

Regarding the male experience in jail, on the other hand, although imprisonment is an admittedly masculine space, little is said about the particularities of men who are deprived of freedom. In fact, one can consider that it is precisely because it is an extremely masculine space that the topic of masculinities is not part of the discussions about the prison system, the masculine being the unmarked gender, the one about which we do not need to speak, the hegemonic.

Although it is recognized that there are several models of masculinity and ways to be a man, it is a fact that some are more valued and legitimized than others, thus being recognized as hegemonic. The concept of hegemonic masculinity was introduced by Connel (2000) and, as far as our Western context is concerned, the most valued characteristics of this masculinity model are the high degree of competitiveness, the inability to express emotions beyond anger, the inability to admit weakness or dependence, homophobia, devaluation of women and all acts, objects, performations and female feelings expressed by men (Kupers, 2005).

As expected, the predominant form of masculinity found in prisons can be defined in terms of aggression, violence, homophobia, and domination. Many men deprived of their liberty hold this dominant identity and seek to be excessively dangerous in order to protect themselves from possible physical and/or sexual violence, since demonstrating weakness in an environment such as prisons can be a risk factor (Pemberton, 2013). This expression of hegemonic masculinity exacerbated by the prison environment was called "toxic masculinity", as it outlines aspects of hegemonic masculinity that contribute to the spread of violent forms of being a man in the world (Kupers, 2005, p.714).

Understanding that prisons are masculine spaces and that gender is a privileged analytical category for the study of power relations in society, we seek, in the present study, to carry out a systematic review of the specialized indexed international literature that contemplates gender issues when studying prison systems. Our aim is to know which themes are being studied concerning the experience of confinement of women and men in prisons around the world.

Initially, the bibliographic review would be done only with studies from Brazil, where the authors were born. The idea was to analyze academic publications in ten years, starting in 2006, the year when the Brazilian Drug Law was enacted. That legislation was primarily responsible for the rapid increase in prisons in the country, especially the increase in female arrests, drug trafficking being the crime that most imprisoned Brazilian women. After assessing the global scenario, however, it has been observed that the increase in female detention is a reality around the world. Thus, the search was extended to all countries, maintaining the previously established time frame (2006 to 2016).

Method

Between January and February 2017, two independent judges undertook a systematic review of the literature in the Scopus, Psycinfo and Virtual Health Library (VHL) databases. Scopus is the largest database of abstracts and citations of peer-reviewed literature. PsycInfo is a database on Psychology, Education, Psychiatry and Social Sciences, edited by the American Psychological Association (APA). The VHL covers sources of scientific and technical health information, organized and stored in electronic format in the countries of the Latin American and Caribbean Region.

The option to conduct such a study was related to the fact that this systematic process is a clear and transparent procedure regarding how research documents were obtained (Walker, 2015). The choice of the aforementioned bases, in turn, was guided by their representativeness and their wide range, permitting the search for articles within the desired theme.

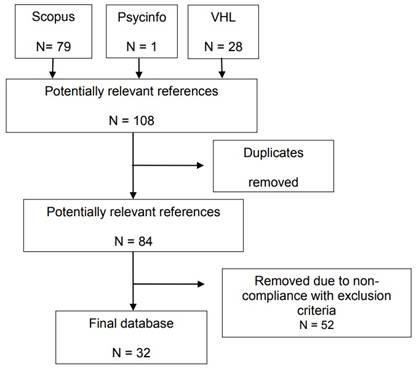

The descriptors selected to trace the publications were: "gender" AND "prison"; "gender" AND "jail"; "gender" AND "penal institution"; "gender" AND "incarceration"; "gender" AND "correctional institution". Included in this search were all texts that were scientific articles published in periodicals, which are peer-reviewed in anonymous form, studies that were published in full in Portuguese, English or Spanish, which belonged to the period from 2006 to 2016 and contained the words gender and prison, with due variations, in the title of the article. The initial search resulted in 108 studies, and after exclusion of 24 articles repeated in the databases; there were 84 references potentially relevant to this review.

The texts were then analyzed based on the following exclusion criteria: to be a theoretical article, to deal with health problems (e.g. constipation), to focus on the underage prison population (below 18 years), and to deal with graduates from the prison system and/or people working in the system. Based on these criteria, 52 studies were eliminated, leaving 32 articles in the final database. Both researchers discussed the divergences at the time of application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and solved them based on consensus. The search procedure is shown below (Figure 1):

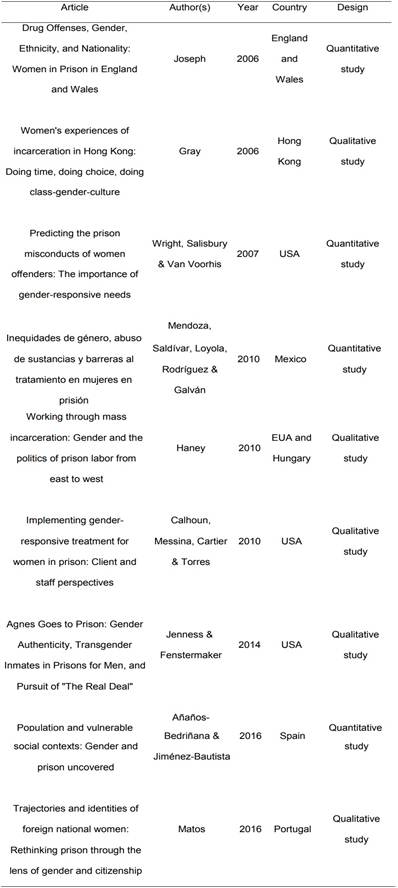

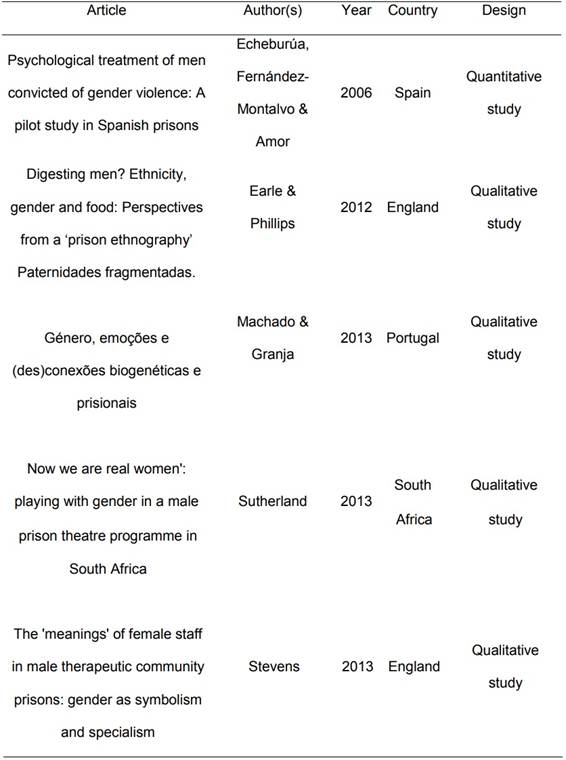

The data for all analyzed articles were extracted and separated in an Excel worksheet, which included the name of the study, the authors, year and country of publication and study design. These components have been summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Results

Regarding the number of publications in the period analyzed (2006-2016), some degree of constancy was identified, being 2010 and 2014 the years with the largest number of articles published, six and seven, respectively. The research profile revealed a predominance of US authors and participants, and 15 of the studies dealt with the prison situation in the United States of American. Next, the countries that published most were Spain (four articles), England (three articles) and Portugal (two articles).

It is noteworthy that Brazil, in the limited period, produced only one publication on the subject. Brazil's lack of expressiveness contrasts with the alarming figures of the prison population in Brazil, which exceeds 700,000 people deprived of freedom, according to national data (Brasil, 2017). In this context, we can identify the extent to which the progressive increase of the prison population in the country, which is accompanied by the terrible structural conditions of its prisons, is not yet considered a priority from the academic point of view.

Regarding the research design, quantitative studies were predominant, the questionnaire (12 studies) being the most used technical procedure, followed by secondary data - database (eight studies). Among the qualitative studies, the most used technical procedure was the interview (five studies). On the participants' profile, the vast majority (18 studies) dealt with mixed prison populations, nine involved only female participants and only five imprisoned men. About the authorship of the articles, we observed that 14 of them were signed only by women, 14 had mixed authorship and four were written exclusively by men. The particularities of each study are described below.

Imprisoned women

About imprisoned women, nine studies were evaluated, one of which was carried out with trans women deprived of freedom in male prison institutions (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014). In this study, authored by a female duo, it was identified that the trans inmates express the desire to be seen and acknowledged as "real" women in a male prison. This desire takes the form of expressions of gender practices that embrace male dominance, heteronormativity and daily acceptance of inequality. All gender practices are carried out within the context of a powerfully heteronormative male environment that privileges men and excludes women.

Among the eight other studies, three dealt with intervention projects within female prisons. Calhoun, Messina, Cartier and Torres (2010), a mostly female quartet of researchers, evaluated the implementation of a specific drug treatment program for female prisoners in the United States. In the program, the participants noted that the reasons that led them to use drugs are related to families, spouses, maternity and the history of violence suffered before the incarceration.

Another research, also conducted by three women and one man, investigated the difficulties the Mexican prison population faced to access drug addiction care services. According to Mendoza, Saldívar, Loyola, Rodríguez and Galván (2010), the search for treatment is directly linked to the established family relationships. Fear of losing custody of children and of not being accepted by other family members are important motivators for them. The barriers to treatment include the lack of knowledge about the service provided and the type of crime committed.

The female researcher Haney (2010) analyzed the differences between two female prisons - one in Hungary and one in the United States - in how they established and perceive work within the prison. In the Hungarian penitentiary, 70% of inmates work in paid employment. Work is understood as empowering and as part of the feminine identity. The difficulties of women prisoners are assessed in social terms, as a result of economic and family problems or arising from the relationship with abusive spouses. In the US prison, there is no paid labor. There, women's problems are understood as individual pathologies and not as a result of social vulnerability. Thus, "female empowerment has come to mean therapeutic recovery" (88).

The other articles dealt with women's trajectories and vulnerabilities prior to incarceration. The mixed couple Añaños-Bedriñana and Jiménez-Bautista (2016) looked for sociodemographic characteristics and social risk factors in the previous life of women prisoners in Spain. The authors observed that most of the participants have trajectories marked by social violations and vulnerabilities that led them to crime, begging or the sale of sex to make a living. Most of them were poor women with low education levels, arrested for drug traffic and with children (almost 80% were mothers). In addition, 31% of the prison population is foreign.

The rest of the articles on female incarceration were written by women only. Joseph (2006), in an analysis of the relationship between gender, ethnicity and nationality and the imprisonment of women in England and Wales, notes that between 1992 and 2002, ethnic minorities in jail increased by 124%, while the prison population increased by 55% in the same period. Likewise, the number of arrests of foreign women increased by 219% between 1993 and 2003, while arrests of British women increased by 169%. These women generally play small roles within the framework of international drug trafficking. Thus, foreign, black, poor women and mothers are hit hard by a "war on drugs".

Similarly, Matos (2016) analyzes the trajectories of foreign women arrested in Portugal. They account for almost 20% of the female prison population in the country. The migratory routes of these women start due to the difficulty to get access to education and quality work in their countries of origin. Paradoxically, the author points out the female agency in the practice of criminal activity in a foreign country, because it was through migration and crime that they gained greater control over their lives.

Gray (2006) also notes the female agency in the study she conducted with imprisoned women in Hong Kong. Investigating the interconnections among class, gender and culture, the author emphasizes that women positioned themselves discursively as active subjects, not as victims, but as people who organize their own lives, within a complex context of vulnerabilities. These relate to poverty, poor access to education and work, violent relationships lived at home and in a highly patriarchal and sexist society. Thus, for these women, the moral and legal transgression of crime represents the escape from pre-established millennial scripts as well as the search to command their lives.

Wright, Salisbury and Van Voorhis (2007) investigated whether gender-responsive needs represent risk factors for engaging in misconduct in prison. The authors noted that the history of sexual violence in childhood, the presence of mental disorders and the lack of support networks outside the prison are predictors of poor institutional behavior. It is noteworthy that women suffering from abusive marital relationships had less behavioral problems in prison, probably because incarceration took them out of a context of constant violence. In such cases, the jail functions, paradoxically, as a protective means for women. Also, it is noted that some gender-neutral needs, such as antisocial attitudes, unemployment and money problems also served as predictors of misconduct in prison.

As a cross-cutting axis in all nine studies on women prisoners, the researchers mention the social vulnerabilities they experience. The poverty (Gray, 2006; Haney, 2010; Joseph, 2006; Matos, 2016), low education (Añaños-Bedriñana & Jiménez-Bautista, 2016; Gray, 2006; Mendoza, Saldívar, Loyola, Rodríguez & Galván, 2010; Matos, 2016; Wright, Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2007), the black race (Haney, 2010; Joseph, 2006), migrations (Añaños-Bedriñana & Jiménez-Bautista, 2016; Joseph, 2006) and the multiple cases of violence suffered (Gray, 2006; Haney, 2010; Calhoun, Messina, Cartier & Torres, 2010; Wright, Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2007) cross the lives of the imprisoned women and evidence weaknesses of the family and social networks prior to their incarceration.

Also, maternity is another recurring theme in the studies analyzed (Añaños-Bedriñana & Jiménez-Bautista, 2016; Calhoun, Messina, Cartier & Torres, 2010; Mendoza, Saldívar, Loyola, Rodríguez & Galván, 2010; Wright, Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2007). Likewise, the impact of imprisonment on children's lives is observed, especially among foreign women, whose bonds are hampered or broken by the distance from the children (Añaños-Bedriñana & Jiménez-Bautista, 2016; Joseph, 2006).

Imprisoned men

Five studies on male inmates were analyzed, four of them on activities developed within the male prison. In the first, Echeburúa, Fernández-Montalvo and Amor (2006) evaluated the effectiveness of a psychological treatment program with men who were convicted of gender violence crimes in Spain. The therapeutic process was idealized by the authors (all men) and conducted by prison psychologists, always in pairs of both sexes. Program participants demonstrated, at the end of the therapeutic process, greater emotional stability and reduced cognitive distortions about women and the use of violence against them.

In another study about mental health, this time conducted by a woman, the researcher Stevens (2013) seeks to understand the meanings male prisoners attributed to the work female therapists performed in a male prison in England. The participants see the female workers either as "mothers" who care for, welcome and manage male feelings or as "lovers" who have intensified their sense of sexual frustration over the impossibility of heterosexual practices in jail.

In the third study, the white, feminist, and middle-class woman Sutherland (2013) presents results she obtained through theater groups she conducted with black, poor and imprisoned men in South Africa. She examines the notions of gender performance and sexuality that arise in this theatrical project. The author emphasizes that, as a rule, for men, jail is a space based on homophobic and hetero-patriarchal behaviors, as well as for the reinforcement of hegemonic masculinity. Thus, the availability and frequency of the performances staged by women, gays, and transvestites in the theater groups is surprising. These plays had a playful character and allowed the participants to interpret and experience roles other than those they usually played in prison.

The fourth research, coordinated by the mixed duo Earle and Phillips (2012), explores another facet unrelated to the hegemonic masculinity, namely the preparation of food and the relationships established between men in the kitchen of an English prison. The place is a "contact zone", where people of different cultures, races and classes interact. In these spaces, remarkably, white men feel that they have less power, seeing the territory dominated by blacks and Muslims. At the same time, the kitchen permits the exercise of other types of masculinity, through the execution and approximation of domestic activities, socially considered as feminine.

The fifth and final study on the male prison population differs from the others, as it does not deal with programs performed within the prison. Two women, Machado and Granja (2013), explore the experiences and perceptions of men arrested in Portugal about paternity. For the interviewees, prison can function as a means to "free" themselves from the ways of life beyond the prison walls and develop a new way of being a father, especially because of the difficulty to exercise the role of provider in the prison. Also, the reproduction of hegemonic models of maternity and paternity in the penal context is observed, in which the women are central in the care for the offspring and the fathers are coadjuvants.

In common, almost all the articles show the social vulnerabilities of the men studied. The authors appointed poverty (Echeburúa, Fernández-Montalvo & Amor, 2006; Earle & Phillips, 2012; Machado & Granja, 2013; Sutherland, 2013), low education, the black race (Earle & Phillips, 2012; Sutherland, 2013) and the different ethnic origins (Earle & Phillips, 2012) as crossing axes. Not coincidentally, these characteristics are observed in most of the imprisoned men around the world.

Imprisoned men and women

Eighteen of the articles analyzed concurrently involved imprisoned men and women. Articles about the different impacts of incarceration were recurrent, considering different aspects, for both genders. The majority (ten) of those studies were written in mixed authorship, followed by five studies conducted exclusively by women and only three by male authors.

The studies by mixed authors covered a more descriptive view of the profile of the incarcerated population (Carvalho, Valente, Assis & Vasconcelos, 2006) and the average time men and women spent behind bars (Hogg, Druyts, Burris, Drucker & Strathdee, 2008). The studies also focused on gender differences in risk factors and protection of suicidal ideas during incarceration (Zhang, Liang, Zhou & Brame, 2009), as well as on life circumstances and major needs after the release from prison (Spjeldnes, Jung & Yamatani, 2014). Studies that analyzed the relation between the sexual satisfaction and psychological health of imprisoned men and women (Carcedo, Perlman, Lopez, Orgaz & Fernández-Rouco, 2015), as well as studies aimed at knowing their attitudes towards homosexuality (Blackburn, Fowler, Mullings & Marquart, 2011) were other themes of interest in articles of mixed authorship.

Another recurring theme was the participation of men and women in drug rehab programs while in prison. In the study by Belenko and Houser (2011), for example, it was identified that, despite evidence that therapeutic interventions for drugs are important for non-relapse, only a minority of the inmates participate in such treatments in prison, with women being more diligent than men. The male and female authors argue that the higher rates of female participation are consistent with the fact that, overall, women use the health services more both beyond and inside the prison.

In the study that was aimed at examining gender differences in the psychiatric disorders of male and female prisoners recently admitted to substance abuse programs in American prisons, according to Zlotnick et al. (2008), this situation can be explained by the fact that women are significantly more likely than men to have a lifetime psychiatric disorder. This statement particularly applies to women who have been incarcerated, as the history of abuse increases the vulnerability of these women, favoring substance use and, consequently, the emergence of severe psychiatric disorders.

In addition to participating in less than women in mental health treatment programs, Celinska and Sung (2014) argue that, surprisingly, men's participation in such programs is related to a greater likelihood that they will violate the prison rules. The male and female authors suggest that the inmates' participation in activities inside the prison enhances their contact with other prisoners, thereby increasing the chances of physical alterations and infractions.

In general, all articles of mixed authors provided data illustrating the particularities of men and women throughout the execution of the prison sentence. While the results of the aforementioned research suggest the importance of particularly addressing gender issues, the results of the study by Freudenberg, Moseley, Labriola, Daniels and Murrill (2007) acknowledge that men also have gender-related needs. Thus, helping men in prison define masculinity in ways that provide healthier choices for being fathers, better relationships with less violence and less substance use can contribute to male health, community health, and public safety.

The understanding that the collateral consequences of incarceration are worse for women generally supported the three studies conducted by male authors. For example, for Massoglia, Pare, Schnittker and Gagnon (2014), women suffer more from the effects of deprivation of liberty, especially with regard to health issues. The authors note that women with a history of incarceration are more likely to die prematurely than women without this history, even after controlling for sociodemographic factors and some covariables related to mortality.

Schnittker & Bacak (2015) in turn, discuss to what extent the traditional gender codes and their implication in victimization are even stronger in prison than in the larger society. Thus, male prison violence is more commonly targeted at men who show weakness or history of past victimization. In the female prison, on the other hand, the culture of care is encouraged, reproducing in its space family structures in which there is a mother, daughters, sisters, etc.

The linkage of women with care and family obligations was another interesting topic in the article by Jiang and Winfree Jr. (2006). The authors identified that, for them, staying away from home and children is the worst part of incarceration, with men rarely expressing any concern about the future of the offspring when they are incarcerated. This is because they know that the parent or other relative will take care of the child, regardless of the time of the sentence. Women, on the other hand, do not have this assurance and can begin to worry about the emotional damage that imprisonment may have in their children's lives, presenting behavior problems in prison.

With regard to the particularities of research conducted by women, we identified a certain preference for issues related to health and access to health services within the prison. In this perspective, studies that dealt with the barriers to the effectiveness of HIV education, prevention and treatment actions within the prison, as well as the differences between men and women in the perception of risk (Alarid & Hahl, 2014) coexisted with research aimed at examining the incidence and suicide rates of male and female prisoners (Dye, 2011), as well as studies intended to explore the gender aspects involved in the practice of self-injurious behavior in men and women deprived of their freedom (Smith & Power, 2014).

In an attempt to answer which areas of women's life are most affected by the prison experience, the Spanish study by the female researchers Herrera Enríquez and Jiménez (2010) identified that deprivation of freedom affects women's self-esteem more significantly than men's, probably because women take on more intimate family roles and the loss of such relationships has a negative impact in their lives. In addition, men have experienced the social rejection delinquency presupposes less, whereas women would feel it doubly: once because they do not play their traditional roles as women, and another because they incorporate roles traditionally intended for men, namely transgression and aggressiveness.

Finally, the ethnographic study by the female researcher Wilson (2008) was aimed at analyzing the graffiti by men and women in a deactivated Australian prison. Throughout the fieldwork, the author was confronted with the fact that jail is a deeply masculine environment, a maxim that applies to prisons that also host women. Among the former penitentiary teams interviewed, the powerful echoes of this tendency prevailed, sometimes manifesting in brazen sexism.

In the main prison units Wilson (2008) visited, former prison officials said that, as a woman, the author could not have a real view of these institutions because there were things going on there that "decent" women should not know of. In addition, they mentioned that female guards should not occupy this place, as they could become emotionally involved with the prisoners. In such conversations, it was also evident that these professionals saw women prisoners as morally "much worse than male prisoners", being incorrigibly manipulative, malicious, and highly problematic.

Although with different objectives and dealing with different realities, all studies involving both men and women deprived of their freedom portrayed a prison population with a relevant history of violence and rupture of family ties, especially women, for whom prison constitutes just another link in a chain of multiple violence along their trajectories.

Discussion

The concept of gender derives from a polysemous field in which very different reading perspectives seek to indicate its conceptual definition. Those perspectives range from more essentialist conceptions that understand it as equivalent to sex, to more critical dimensions of analysis, which bind it to the concepts of identity constitution or even associate it with a social construction. The fact is that gender encompasses a multitude of interpretations.

As already mentioned, the notion of gender sustained in this article is based on the understanding of this concept as a social construction and stage of unequal relations of power. An understanding that opposes the essentialist constructs that bind sex to gender in a fixed and uncritical way (Scott, 1995a). However, the analysis of all the articles in this review revealed that many of them understood gender as a dichotomous variable with the instances gender / sex. This was especially clear in studies that concomitantly involved imprisoned men and women as participants. Rather than critically addressing the different impact and experience of incarceration for both, the articles only used the concept as a way to descriptively differentiate the collected data.

In addition, it was also evident that the studies with mixed populations that sought a more critical position of the concept of gender mainly focused on the specificities of female prisoners, without discussing the reality of the men in that context. It is well known that the incorporation of the gender theme in the scientific terminology of the 1980s played a key role in the political acceptability and academic legitimacy of research that was based on women's issues. This is because the replacement of the term "women's history" with "gender studies" dissociated the studies produced from the politics of feminism. Thus, the use of the term gender included the study of women, but without naming them, and did not constitute a critical threat to current standards (Scott, 1995b).

Nevertheless, it is based on a conception of gender understood from its relational perspective. In other words, gender as a theoretical marker in which equality and difference in the constitution of masculine and feminine subjectivities can be thought simultaneously. Based on the articles selected in this review, however, it was evident that, even in studies that seek to work with men and women simultaneously, the focus still rests almost exclusively on the needs of women deprived of their freedom. In this context, one can consider that the interest aroused in the particularities of female prisoners, despite the specificities of men in the same context, is due to the belief that violence, aggression and transgression do not belong to the feminine nature and should therefore be a priority subject in research.

In this sense, research seems to be oriented according to socially established gender patterns. In general, the authors tend to study issues related to the social and family relationships of women prisoners. The links with the children and the suffering resulting from the absence of the offspring is a recurring theme among the female prison population, whereas only three studies deal with fatherhood among men. In the same way, women's trajectories of life are highlighted, suffered by violence, while men are given the role of perpetrators of aggressions, being rarely positioned as victims of aggression.

Also, in studies on mixed prison populations, as well as in research dealing with men and women imprisoned in isolation, the frequency of the mental health theme and access to health services is noted. Drug addiction, self-injurious behavior and suicide are recurrent scientific problems in this review, especially in US-led research. Usually, these studies from the US seem focused on individual deviations, not on the social structure that leads to mental disorders. It is also worth noting that only one research (Alarid & Hahl, 2014) adopted HIV / AIDS as its main research focus, being a health problem that has historically been linked to the prison system. Thus, when we look at recent studies with a gender cut, AIDS does not seem to be the central health issue in prison. The focus of the analysis is on mental issues and the relationships between female and male prison populations and drug use.

The way these issues are addressed differs between imprisoned women and men though. They point out that mental disorders and drug addiction are due to the weakening of social and family ties, as well as the multiple history of violence suffered before imprisonment. Concerning men, the interventions analyzed seek ways to reduce and prevent acts of aggression against themselves or against women.

Thus, as a rule, studies on women deal with relationships beyond the walls. The focus is on the prior life, before the jail. On the other hand, research on the male prison population is mostly about the dynamics established within prisons, among men in prison and between inmates and prison staff.

About authorship, it is noticed that most of the articles, whether about the female, male or mixed population, are signed by women. In only three studies (Stevens, 2013; Sutherland, 2013; Wilson, 2008), however, the authors questioned the impact that gender, race and class have on research development. Such recognition of the researcher's socio-political position was not found among the other authors of the articles analyzed in this review.

Considering the studies that have been listed for this review, it is evident that the advances felt academically in the theoretical discussion about the concept of gender - understood as a social construct beyond the perception of statistical variable - are not being followed with equal intensity with regard to the problematizations of this concept from the prisons. This is because, although all the articles selected here contained the word gender in the title, ironically, few studies used this theoretical operator critically.

That said, it is important to note that studies that deal with the prison system should reach an increasingly complex and critical theoretical-conceptual level and demonstrate greater articulation with social markers, such as race, gender and class. When analyzing countries that are present in the systematic review, we observe that US and Brazil, both marked by centuries of slavery of African people, have the racial marker as one of the determining factors in incarceration (Brasil, 2017, Davis & Dent, 2003, Wacquant, 2009). In Australia, Aborigines account for 30% of the local prison population, although they represent only 2% of the Australian general population (Davis & Dent, 2003). In England, Portugal and Spain, nations that have colonized different countries and continents, the number of foreigners and immigrants who have been confined in prisons has grown (Añaños-Bedriñana & Jiménez-Bautista, 2016, Joseph, 2006, Matos, 2016). Given incarceration and power tensions in social relations, racial and ethnic issues are intimately connected with poverty (Wacquant, 2009), especially in the case of non-white and/or foreign women (Davis & Dent, 2003). Thus, we stress the importance of studies on the specificities of the prison population to avoid the non-segmentation of the various mechanisms of exclusion that cross the life of the usually imprisoned world population, in order to avoid reductionist and decontextualized interpretations.