1. Introduction

The phenomenon of abuse experienced by women in their conjugal relationships is a very serious problem, which has increasingly become socially alarming and has promoted professional actions to provide with the victims with coping mechanisms. (Menéndez, Pérez, & Lorence, 2013).

Violence perpetrated against women has always existed and, according to the results obtained in the Western world, we would not mistaken to assert that it has been taking place in many cultures and in different historical moments. However, “the interest in analyzing and understanding this matter, the first statements and guidelines of international agencies, and the implementation of legal and professional measures for coping with this matter began in the last two decades of the last century” (Lila, 2010, p. 42). Currently, there is extensive research addressing gender-based violence, which ranges from macro-knowledge of the problem and its roots to the knowledge of the idiosyncrasies and particular situations of the individuals who experience it.

Primarily, in order to specify the matter within the vast literature on the subject, it is necessary to conceptualize what gender-based violence in a conjugal relationship is.

We find definitions such as McCloskey's (2016) that assert gender based violence as: “abuse of groups targeted because of their gender or gender roles and are relegated to a lower position of social status or power” (p. 153).

Abuse perpetrated against the victims may occur in the physical, psychological/emotional, institutional, economic, and sexual spheres. This way, it is possible to observe that abuse may be perpetrated in several areas, combining among them and, always, endangering the rights and dignity of the victims. According to Velásquez (2003), every kind of abuse is frequently perpetrated, which turns gender-based violence into a social problem. It generates physical (bruising, injuries, traumas, etc.), psychological (humiliation, low self-esteem, feelings of inferiority, among others), economic and social consequences for the victims.

After the emergence of some cases reported by the media in recent decades, gender-based violence has become a "public" matter. It has forced the authorities to take measures in the form of laws, as for example in Spain the Organic Law 1/2004 was enacted in order to prevent violence and protect the victims. There is evidence of recent efforts to raise the population's awareness of prevention and to empower the victims with resources from institutions.

There is also some agreement that many women who experience gender-based violence from their intimate partners are able to end the conjugal relationship, despite facing many obstacles. In this sense, they are strong enough to overcome traumatic situations by accessing internal and external resources that allow them to be free from violence (Alencar-Rodrígues & Cantera, 2013). However, as indicated in a study conducted by Menéndez et al. (2013), the most common fact is that women do not react in a radical and clear-cut manner from the first episodes of abuse and tend to bear the situation for a variable time which is often significantly long.

Some authors, such as Miracco et al. (2010), stress the importance of coping strategies used by women who experience violent situations to find a healthy solution to the problem. These resources would be included within the concept of coping, which is defined as cognitive and/or behavioral efforts made to handle specific external/internal issues that generate stress (Folkman, 2011). It is possible to make a distinction between strategy, as a method of coping that is contingent upon the situation, and style, as a set of coping strategies associated with various scenarios.

Folkman (2011), states that coping styles are usually classified into: problem-focused, emotion-focused and problem assessment-focused. The first style refers to efforts aimed at modifying or eliminating the stress source by finding a solution. This behavior tends to have more positive effects on relationships. The second style refers to efforts aimed at regulating the emotions derived from the situation; however, this style gives worse results. The third style is aimed at modifying the initial assessment of the situation, which tends to reassess the problem.

According to Miracco et al., (2010), strategies that facilitate an approach to the problem, a search for a solution, or the modification of the situation would be considered positive. On the other hand, passive or avoidance coping strategies that are rigidly conformed hinder the resolution of the problem, thus resulting in dysfunctional strategies. Roco, Baldi, & Álvarez (2014) reported that:

The phenomenon of physical, verbal, and psychological violence experienced by the participants had been frequently faced with a passive attitude toward the perpetrators, tolerating the abuse situation and hoping the problem would positively solved itself as time went by. This attitude would pose great difficulties to eradicate the cycle of domestic violence (p.42).

With respect to the selection of specific coping responses, it is relevant to consider the degree of controllability that the stressful event has. It has been shown that “the perceived controllability of the stressful event affects the type of strategy used and its effectiveness to reduce the degree of stress (Matlin, Washington, & Kessler, 1990, p. 306)” (Mikulic & Crespi, 2008). In this line, previous studies (Mikulic & Crespi, 2003) have identified a predominance of avoidance coping responses related to the perception of not being able to manage the situation that had created discomfort, since there was a multiplicity of variables that were beyond the control capacity of the individuals.

The resources used by women can range from the search for social support to strategies to maintain an "inner balance". Within this wide range of possibilities, it seems important to point out the perception of social support, which has been highlighted by several authors (Herrera, Agoff, & Rajsbaum, 2004; Juárez, Valdez, & Hernández, 2005). Several studies have shown that the impact of social support is beneficial in domestic violence situations (Hage, 2006; Rodríguez et al., 2009). However, only a few studies have assessed the relationship between social support and the vulnerability of victims, despite the fact that several studies have pointed out that participation in social life decreases as abuse increases (Juárez et al., 2005).

Social support can be defined as a set of expressive or instrumental provisions-perceived or received-provided by the community, social networks, and trusted individuals, both in daily life and crisis situations. (Rodríguez et al., 2009). According to Fachado, Menéndez and González (2013), some authors have indicated the existence of two dimensions that shape social support: structural social support and functional social support. The first relates to the social network, i.e., the amount of social relations that an individual has at a given time. The second can be defined as the perception of support availability that an individual has. This type of support is home to the beliefs about the extent to which individuals are loved, cared, and protected by those who are part of their social networks. In addition, functional social support consists on other types of support that can be divided into: emotional, informational, instrumental, affective, and positive social interaction.

A qualitative study conducted by Herrera et al. (2004), found that women who seek help to solve the problem of conjugal violence usually turn to individuals who are close to them. On the other hand, women who do not have a strong social network prefer to make use of health services. Another study conducted by Juárez et al. (2005)found that the feeling of loneliness is one of the main symptoms exhibited by women victims of gender-based violence resulting from conjugal conflicts. The feeling of loneliness and isolation from people who were close to them, usually associated with the controlling behavior of the intimate partner, contribute to the perception of the victims that they have few individuals to turn to.

The assessment of the coping strategies used by victims of gender-based violence is of great interest due to the following reasons:

It explains how women live during the abuse situation, providing data about their subjective experiences.

It provides information about the target of the efforts made to manage the situation and, in this regard, indicates which strategies were appropriate or inappropriate to bring about positive change.

It can help professionals elaborate performance targets.

Studies addressing coping strategies and the resources used by abused women are still scarce and insufficient. This fact is shocking given the great importance of these studies during the occurrence of the problem and its outcomes.

This way, we formulated the following questions: (a) What were the coping strategies used by women victims of gender-based violence?; and (b)How were their social relations configured before, during, and after their conjugal relationships?

In response to our research questions, we proposed the general objective of understanding, through the discourse of women who had experienced domestic violence, how they had faced the problem of gender-based violence and their perceived social support network before, during, and after the conjugal relationship.

The specific objectives were:

(a) To describe the coping strategies used by these women during the abuse situation and the phenomena that enabled their use.

(b) To analyze the perceived social support network as a resource before, during, and after the abuse situation.

2. Method

2.1. Design

This research is carried out by following a qualitative methodology (descriptive and exploratory). The use of this type of methodology aids the understanding of the phenomena people suffer as well as the reality in which they find themselves. The qualitative technique of choice was the semi-structured interview because it allows one to inquire into people's experience.

2.2. Participants

Five women who had experienced gender-based violence participated in the study. All of them came from the province of Barcelona and they aged 35 to 74, the average age being 56 years. A short description of the women follows (their names have been changed):

Mercedes: She is 50 years old, lives in the province of Barcelona and has two daughters. Her marital status is single and she has secondary education.

Cristina: She is 61 years old, lives in the province of Barcelona and has two daughters and two sons. Her marital status is single and has regulated studies on trade.

Laura: She is 74 years old, lives in the province of Barcelona and has two daughters and one son. Her marital status is single and she has studied administration and commerce.

Helena: She is 35 years old, lives in the province of Barcelona and has two daughters. Her marital status is single and she has studied a career in primary education.

Esther: She is 61 years old, lives in the province of Barcelona and doesn't have any daughters or sons.Her marital status is single and she has secondary education.

The participants were recruited in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, and they were contacted through associations and social networks. We used convenience samples and the exclusion criterion was experiencing physical, psychological, and sexual violence perpetrated by their intimate partners while the interviews were conducted. Being a victim of gender-based violence at some point in their lives was the inclusion criterion.

2.3. Instruments

We followed a qualitative methodological approach, which revealed the need of using an instrument to allow a detailed assessment of the participants' experience. To this end, we designed a semi-structured interview including the following topics: gender-based violence, coping strategies and social support.

The interview was designed through an exhaustive review of the literature, taking the current scientific evidence of this phenomenon as a starting point. We took into account the emotional impact that the questions might have on the participants, gradually increasing its intensity as an appropriate rapport with the interviewer was established.

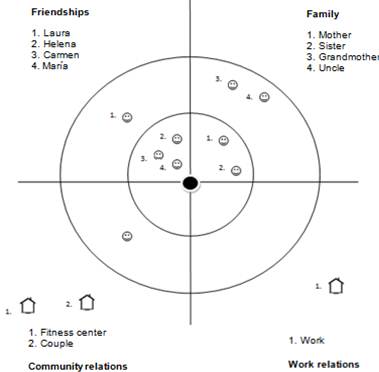

The purpose of the interview was to collect the necessary information to achieve the goals of the research. With the aim of investigating the participants' social relations and perceived social support, we draw support maps based on Sluzki's proposal (1993),which considers the creation of four areas, namely: family, friends, community relations and work relations. Three circles hall be included within these four areas referring to the degree of closeness to the victims. The inner circle refers to intimate relationships, the middle circle to close relationships-with a lower level of commitment-and, finally, the outer circle referring to relationships with acquaintances. The resulting figure would be the interviewee's social network.

2.4. Procedure

The interviews were conducted according to the participants' convenience and in a quiet environment that allowed creating an environment of trust. They lasted from 30 to 60 minutes. The selected women were informed about the used methodology and the goals of the project. They signed an informed consent form in order to be included in the research. The necessary information was included in this consent form so that the participants could understand the purpose and the phases of the study. We also included information on the participants' anonymity and the confidentiality of the information they could provide. The participants were also informed that they had the right to abandon the project if they considered it necessary. In order to preserve the women's anonymity, we decided to use fictitious names (Mercedes, Sofia, Helena, Laura, and Cristina) in order to disclose the narratives to the readers. Firstly, the semi-structured interview was conducted and recorded with a voice recorder. Then the support maps were drawn, making sure that women took part in the reconstruction of their social support network before, after and during the abusive relationship.

2.5. Analysis procedure

The interviews were audio-recorded and the InqScribe software was used to get the transcription. We created different categories (gender based-violence, coping strategies, social support and self-care) to perform the analysis of the women's discourse, taking into account the different dimensions established for the organization of the data. These categories were checked repeatedly through the rereading of the transcript and discussions held with the research team addressing violence experienced in conjugal relationships and at work. Our goal was to collect all the data concerning the phenomena revealed by the discursive process.

3. Results and discussion

First and foremost, it is important to note that the women interviewed in this investigation suffered a process of change (in relation to what they did or felt) during their abusive relationship. This implies that the coping strategies utilized by them, as well as their perceived social support, changed or was modified according to the demands of the situation they faced. This process leads us to consider coping as a dynamic and changing phenomenon subject to external experiences and psychological variables.

The first goal of the present study was to describe the coping strategies employed by the women interviewed throughout the abuse situation inside of the conjugal relationship. We found that the strategy most commonly used by these women to deal with the situation was avoidance. Other studies have indicated similar results (Miracco et al., 2010; Moral de la Rubia, López, & Cienfuegos-Martínez, 2011; Roco et al., 2014).

Coping strategies include: cognitive avoidance; acceptance/resignation; and search for gratifying alternatives. Cognitive avoidance turned out to be the most frequent and shared by all the women interviewed. This strategy, which involves cognitive attempts to avoid thinking about the problem (Mikulic & Crespi, 2008), is reflected in the constant efforts made by women to keep their minds busy, spending time out of home, focusing their thinking on childcare, or keeping strict routines as normal as possible, among others.

We found many examples in the discourse of the participants: "I was confused and lost, and if I was with my daughter I just focused on housework, on getting things going at home and on work" (Mercedes). Through the women's discourse, we infer that cognitive avoidance was a common recourse used to face continuing abuse. This strategy allowed them to focus their lives on other aspects, circumventing the conflict with the intimate partner. An example can be found in Cristina's words: "I just tried to be with my kids and think that all this will end, that all this would end... I tried to think about it as little as possible".

Regarding the acceptance/resignation strategy, whose goal is to react to the situation by accepting the problem (Mikulic & Crespi, 2008), the women interviewed reported that after a period of time marked by confusion, they ended up giving up and accepting what might happen to them, undertaking actions aimed at promoting the well-being of the family without making anything that could lead to conflicts. Therefore, they described a resignation situation as reported by Helena: "He made me feel inferior in front of everyone with silly and absurd comments and I looked at him but I kept my mouth shut. Somehow I consented". The search for gratifying alternatives, which consists of seeking alternative satisfaction sources (Mikulic & Crespi, 2008), is reflected in the history of these women who explained the things that made them feel well within the complexity of their lives. Among these actions, we can find taking a walk, keeping the mind busy, staying with the family, reading, or writing. These tasks were vital for these women because they allowed them to preserve their good mood. It is important to stress that the participants did not mention resignation, inner refuge, and acceptance as methods for coping with everyday life. They performed actions to alleviate anxiety and avoid the negative emotions caused by the violence situation. These data are consistent with those found by Roco et al. (2014), who stated that women victims of violence would try to avoid thinking about the problem, since they would not tolerate the emotional burden involved in daily life violence.

One of the participating women, Helena, reported how she reacted to anxiety: "I suffered from anxiety, when I was anxious and I turned to eating and... smoking, I felt better at that moment, but afterwards everything was the same, so it wasn’t of much use”. Although avoidance strategies were a necessary palliative for these women, it is observed that they hindered the end of the abuse situation, thus becoming dysfunctional. Other authors have found similar results, such as Miracco et al. (2010) who stated that these strategies can be targeted at reducing the discomfort; however, they just do it for a short time. The discomfort is not only kept in the long term, but it increases. Moral de la Rubia et al. (2011) found that avoidance and passivity are predictor elements of violence experienced in a conjugal relationship.

Despite the fact that these women had mostly used avoidance coping strategies to handle violence, it is observed that, at some point in their lives, each of them had also resorted to approach strategies. Their purpose had been to promote a change in the intimate partner or in the relationship to solve the problem. As found in a study conducted by Miracco et al. (2010), coping with this problem can be time-consuming and, therefore, approach or avoidance strategies are combined in very complex dynamics. Along the same lines, Holahan, Moos and Brennan (1997) demonstrated that coping responses vary according to the severity of the stressor agent. The larger the number of negative life events and chronic stressors, the less they used approach responses to deal with the problem. As a result, there is an increased use of avoidance responses.

The approach strategies found in our study were logical analysis and resolution of problems. The logical analysis strategy would be mainly based on cognitive attempts to understand the situation and be prepared for the consequences (Mikulic & Crespi, 2008). For example, Mercedes explains: "I did not give importance to what he was doing, I thought it was just a phase and my daughter was everything to me".

We found several explanations that women gave to themselves in order to understand what was happening: "I don't know whether because of his addictions or insecurity, he fell... I guess, into depression, and he sought revenge on me..." (Laura). From the interviews, it is possible to infer that these explanations served as a mechanism to justify the perpetrator.

The problem-solving strategy refers to behavioral efforts targeted at solving the problem (Mikulic & Crespi, 2008). In this regard, the participants reported they had made various attempts to address the problem. These are some examples: "I made two attempts to go away... two very weak attempts, I may have been a coward, I don't know" (Laura); "Initially, I tried to talk..." (Esther); "I used to talk to him, I asked for explanations... when he was calm, I thought that I could do something in those moments" (Mercedes).

All the participants had used approach strategies, especially at the beginning of the conjugal relationship, in face of the perplexity of the events. They tried to find solutions targeted at dialogue, understanding, or confrontation. However, it is possible to observes change in strategies as the events went on. One phenomenon that could be managing the use of strategies targeted at approach or avoidance is the perception of controllability of the events. The discourse of the participants revealed that they did not find a balance between their behavior and the stressful event, causing the feeling that the event was uncontrollable. This fact led to a shift in the locus of control before and after the violent episodes, i.e., from internal to external. In a study by Bolívar and Rojas (2008) it is stated that people with an external locus of control are prone to adopt apathetic and conformist attitudes as they believe that external factors will determine their lives. Nevertheless, the internal locus of control is associated with self-efficacy and taking control of the events.

While after the first abuse episodes women resorted to approach strategies (finding a solution to the problem, talking, etc.), during and at the end of the conjugal relationship they chose strategies targeted at avoiding any kind of confrontation (avoiding the conflict, thinking about other things, looking for alternatives for their well-being, among other possible strategies). The following are some examples: "I had already tried not to provoke him or say anything... but it was inevitable, anything, comment or gaze..." (Mercedes); "I learned the hard way, I learned that the more I asked, the worse I was, and the years went by..." (Cristina); "The situation could not be changed, because if you were polite, you made a comedy and if you weren’t, it was the opposite..." (Laura). These women reported their inability to predict and control what was happening and this fact generated their great feeling of vulnerability.

The assessment of these women's discourses howed that there was another phenomenon closely related to the perceived control, which could prove crucial for the choice of coping strategies in response to abuse. The respondents reported a learned helplessness behavior as the violence progressed. According to the American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology (American Psychological Association, 2007),

learned helplessness is defined as lack of motivation and failure to react after exposure to unpleasant events and, as a result, the individuals have no control over these events. Individuals learn that they cannot control their environment. This way, they are unable to make use of the available control options they have (p. 393).

This phenomenon can be observed in this excerpt from the interview with Mercedes: "I felt powerless due to his verbal and non-verbal attacks; I felt useless and did not react". There is another example found in Helena's words: "Then, as I saw the situation getting worse, I said to myself: I can't escape from this; and I just did nothing... I just let the days pass by, that's it”.

Our results were in line with the learned helplessness model proposed by Walker (1979). According to this model, a woman subjected to uncontrollable events-in this case gender-based violence-will undergo a psychological state in which reaction responses will be blocked.

The second goal proposed in the present study was to describe the perceived social support network that the interviewed women had before, during and after the conjugal violence. We decided to assess the perception of social support due to its importance as a resource to end the abuses (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Map of the perception and social support networks before the conjugal abuse situation. Participant: Helena

To assess this issue, we decided to draw the map of the perception of social support and networks that these women had before, during and after the conjugal abuse. These maps can be seen in Figures 1, 2 and 3. The said maps are organized in the following way: they are divided into four quadrants representing friends, family, community relations and work relations. Likewise, there are three circles: the inner circle contains the most intimate relationships, those people who are seen as a reliable support and who can be counted on immediately. The middle circle is for close relationships with a lower level of commitment, whereas the outer circle is the place for relations with acquaintances.

Regarding the perception of social support before marriage, these women reported that they could count on two or three close individuals in case they needed some kind of help. These individuals were mainly a friend, a sister or a mother. "I could count on my mother, my sister and... two friends that I had, real friends, you know, I could always count on them, a great deal of trust" (Helena). The participants reported that they had a satisfactory social life before the conjugal relationship. They also mentioned not having felt the loneliness that they would experience throughout their conjugal relationship.

Figure 1 is the map drawn by asking these women about their social life before the conjugal relationship and who they could count on in case they needed help. As we can see in Laura’s case, she had a satisfactory social network and her perception of social support was positive. We found multiple significant relationships, mainly with family members or friends. Our data indicate that she was in a satisfactory situation and the analysis of her discourse indicates that she felt accompanied and satisfied with her social life (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Map of perception of support and social networks during the abuse situation. Participant: Helena.

In these women's discourse, we also found a turning point (which varies according to the life of each woman, either the estrangement or the break-up with family and friends) in which, as a result of violence, they started distancing themselves from the people that had been important to them at some point in their lives. Several authors have reported similar results (Juárez et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2009).

When we assessed the perception of social support that the participants had when they were married, we found that their social life had dramatically decreased, as stated by Cristina "that kind of violence means that you cannot go away even if the doors are open. You are in a cage, because violence makes you stay away from people". We also found that they had nobody to count on or they had just one person; and, even though they had a positive perception of social support (i.e., the conviction that they had someone to turn to),they had no access to their support network. Our results are in line with those obtained by Buesa and Calvete (2013), who reported that 72.9% of the participants in their study declared that they lacked support from one important person whereas social support from their family and friends stood at 30%. A good example of the latter can be observed in Mercedes' words: "If I had told them what was happening, I would have counted on them and they would have supported me, but I couldn't tell them anything...”. From the discourse of the participants, we can infer that, as a result of the abuse, they experienced feelings of loneliness and isolation: "I felt lonely because I couldn't tell them everything I wanted. That kind of loneliness is different, very different" (Helena).

Figure 2 illustrates our results graphically. The comparison between Figure 1 and 2 reveals that the loss of social network is evident as the conjugal relationship proceeded. It is also possible to observe a drastic decrease in perceived social support. The pattern of Helena's relations can also be observed in the other cases.

The majority of the participants reported that they did not speak with anyone about what was happening at home. The reasons that explained their silence were: judgments that others could make, social rejection, feelings such as fear and shame, and the conjugal partners' efforts to isolate them: "I did not tell anyone what was happening because I was afraid, he used to threaten me..." (Cristina), "I did not tell anyone what was happening because I was ashamed of what they would think... that I was allowing this situation having two small children..." (Helena). In line with our findings, Rodriguez et al. (2009) affirm that denial and fear of social rejection often prevent women from seeking help.

A study conducted by Juárez et al. (2005) found that, due to the marital dynamics, the perception of these women is that they have few people to turn to. The fact that they do not have significant ties with other individuals is in part a result of the controlling behavior of their conjugal partners. The comparison of our results with those of that study emphasizes certain similarities. It is worth mentioning that the truly worrying aspect in the discourse of our participants was not the perception of having few people who were close to them, but being unable to share it with them. Helena's report is an example:

Yes, if I had explained to them what was happening, I would have counted on them, and I would have been supported, but the thing is that I couldn't tell them anything... because of embarrassment, fear of what they would have thought…

Finally, our data indicated that the respondents increased their social life and their important relations after the end of their conjugal relationships(Figure 3).

Figure 3 Map of perception of support and social networks after the abuse situation. Participant: Helena.

They affirmed that they were more satisfied because the feeling of loneliness had disappeared. The case of Helena illustrated in Figure 3 is an example of our findings. It shows the increase in her social relations after the end of her conjugal relationship. The comparison between Figure 1 and 3 indicates that the social network and perceived social support were similar to those she had before the conjugal relationship. The reestablishment of important social relations is perceived(the perception of social support increases) and new agents appear (intimate partner, activities outside the family environment, etc.).

The present study also focused on assessing the resources that these women used to finally end the conjugal relationships. In all cases, after a key episode in their stories, these women had access to their support network again through a key person, such as a neighbor, sister, friend, or mother. These new relations allowed them to take the first steps toward a solution, thus ending the secrecy that had characterized their lives for years.

4. Final considerations

Based on the analysis of the data obtained in the present study, it can be affirmed that the women interviewed mainly used avoidance coping strategies with an emotion-focused style. There are several phenomena that may influence the choice of strategies, such as a locus of external control or psychological disturbances, e.g., learned helplessness. The analysis conducted in the present study revealed a problem regarding the choice of resources to overcome the abuse situation. If women have no control over the events, they will choose avoidance strategies focused on their feelings, which impede the search for effective solutions. The choice of coping strategies is a multicausal phenomenon influenced by processes related to the type of stressful situation and cognitive aspects of various kinds.

With respect to the second issue assessed, the participants reported the same pattern in their social relations before, during and after the conjugal relationship. This pattern was characterized by a significant loss of social relations and a decrease in the perception of social support as a result of the abuse experienced during the conjugal relationship.

The analysis of the resources that women used to end the conjugal relations hip revealed there integration into the support network, as well as the implementation of approach strategies focused on the problem. As well as other authors, we see the search for social support as an intermediate type of coping. Change in strategies and new social relations are necessary to mobilize women and end the conjugal relationships. Thus, we can conclude that the support network is an essential resource for them, since it becomes a link between "home privacy" and the "outside world".

A more thorough assessment of the obstacles encountered by women to gain access to their social support network highlighted the importance of thinking that they had certain rights and obligations as women. Our data confirm that the fear of social rejection and the conviction of having to comply with social norms had been compelling reasons to remain in silence. This issue, which initially seems intimate, becomes a macro-social issue that transcends from the personal sphere to prevailing social norms. For this reason, we stress the importance of social education on gender issues, as well as the need to involve and mobilize a multitude of social agents (teachers, health professionals, media, etc.) in order to raise awareness and, therefore promote actions to allow the advance towards an egalitarian society in terms of gender.

Finally, we consider that it is still necessary to conduct further studies to understand the attitudes and actions of women who are abused by their conjugal partners. This growing investigation should lead us to detect the dysfunctional patterns that prevent women from ending conjugal relationships. A proposal for future research would be to assess the active victims' self-care, i.e., the actions they carry out to promote their well-being and that of those around them. The findings of our study indicate an important connection between coping strategies and these women's active self-care. The close correlation between these two phenomena leads us to reflect on the protective role that they could be exerting against continuing abuse. For this reason, it would be convenient to analyze them thoroughly.

In addition, it is worth mentioning that, in spite of the efforts made by public and private institutions and the growing interest of numerous groups, the intimate character of conjugal relationships poses a challenge to the professionals involved as it makes it more difficult for victims to open up. The results of our study confirm that coping strategies used by these participants were dysfunctional. However, how can we influence the way a person confronts such a situation? That is to say, is it possible for social institutions to influence the attitudes adopted by abused people? Is it possible to provide social education that would teach people not to face problems in a certain way? The answers to these questions could be found by conducting further studies.

The conclusions drawn from the present study highlight the importance of having support to initiate the process of change. Therefore, the lack of access to the social network is an issue that should be studied. Future research could be based on the analysis of the obstacles (social, personal, intimate, psychological, etc.) that women encounter to seek help from those people they can rely on.

Violence against women is a personal and social problem with many different facets. This way, investigation and intervention should go hand in hand in their struggle. We suggest that further studies assess the data found in the present study in order to gain more in-depth knowledge about gender-based violence and coping strategies.