1.Introduction

During the last decade, several interpretations about regionalism in South America proliferated in order to reflect new trends of regional cooperation that go beyond and were encouraged by a new political momentum. However, those explanations lack a homogenous justification about why this has happened and particularly about how this new phase has affected regional cooperation.

Since Unasur Constitutive Treaty entered into force in May 2008, a new process of regional cooperation began with distinctive characteristics that required new concepts. Most of the debate on regionalism in Latin American was based on economic integration, Unasur poses an interesting opportunity in order to evaluate a regional organization focused on social and political topics avoiding the traditional trade agenda. This shift in terms of agenda posed new challenges to the conceptualization of regionalism based on regional cooperation rather than a traditional regional integration view.

Regional agreements such as Unasur question the «bifurcation between (rather classical) regional cooperation on the one hand, and regional integration on the other» (Börzel, 2011, p. 15). In fact, Nolte (2017) argues that regional integration and regional cooperation are two opposite ends of a continuum of regionalism equivalent to the intergovernmental versus the supranational poles. In this sense, we consider that Börzel (2011) definition of regional cooperation as opposite to regional integration poses a conceptual confusion to the literature dedicated to regionalism, since both intergovernmental and supranational regionalism encompasses different levels of regional cooperation.

Moreover, the South American case poses new questions that go beyond the dilemma between cooperative and integrative agreements. In this case it is adequate to ask why the level of cooperation varies in time and which ones are the main factors that explained the variation. More importantly, since politicization is key in order to understand the South American regional cooperation dynamics, the paper analyzes if and how shifts in ideology of the main members of the initiative affect regional cooperation. Taking Unasur as a case study, this paper intends to explore the following question: How the level of cooperation in Unasur is affected by the dominant ideology of the key members and their leadership dynamics? In the case of Unasur the literature has put a strong importance on the rise of left-wing governments as one of the main explanations of post-hegemonic/post-liberal regionalism emergence, however the debate lacks an in depth discussion about the role of ideology and its combination with different leaderships to explain patterns of regional cooperation.

Despite that Unasur has faced an institutional crisis since 2014-2015, we selected the period 2008 to 2015 for several reasons. First, from 2008 to 2013, Unasur experienced a dynamic cooperation due to the ideological convergence and politicization of regional cooperation in topics related to infrastructure and health. Nevertheless, during those years some of the 12 councils created in Unasur did not show any progress since its creation. Second, from 2013 to 2015, Unasur started to show its weaknesses due to the budget reduction, the absence, the invisibility of the former Secretary-General Alí Rodriguez, and the lack of interest of the presidents to attend the annual Presidential summits.

Various authors highlight the importance of presidential diplomacy and the ideological components as the booster of regionalism in South America. The literature has focused on the causes of this shift (Riggirozzi and Tussie, 2012, Legler, 2013, Petersen and Schulz, 2018) being the most important alleged reasons the rise of numerous left-wing governments at the beginning of the 2000s that allowed the constitution of Unasur. However, other authors (Caetano, 2009, Malamud and Gardini, 2012, Quiliconi and Salgado 2017) argue that even though there was an ideological coincidence of governments in power, the outcome of regionalism is still uncertain and ideological convergence has not acted as an engine to deepen regionalism rather generating a proliferation of new organizations. We agree with these authors showing that ideological coincidence is not sufficient to explain regional cooperation patterns.

Those administrations prioritized social agendas and abandoned Washington consensus policies and challenged the hegemonic role of the u.s. in areas such as military and police cooperation, sharing hostile or indifferent attitudes towards the u.s. in a context in which the traditional hegemonic role of the u.s. vanished. In fact, in a more recent work Riggirozzi and Tussie (2018) point out that those contending actions in regional politics have been a genuine way of reclaiming the redefinition of what governance is about in a way that is at odds with the typical Washington consensus neoliberal governance.

In this sense, Riggirozzi and Tussie (2018) state that there are quite different versions of post-neoliberalism in South America, assuming that post-neoliberalism is still the dominant the game in the region. However, these assumptions can be reviewed in two senses. First, despite that Brazil showed to be a potential leader in the region, during the 2000s the u.s. presented a pretty active involvement in countries with which they have signed bilateral trade agreements such as Chile, Colombia, and Peru. On the other hand, the u.s. security alliances with Colombia hindered the implementation of a deeper regional cooperation agenda in defense and drug trafficking.

Second, regional cooperation in South America has been mainly analyzed based on trade policies and social issues, leaving aside other areas of great importance for the South American states, such as security. In this regard, the empirical analysis of this paper focuses on the variation of regional cooperation in two main areas of security: defense and drug trafficking.

We selected these topics for two main reasons. First, those two councils showed dissimilar patterns of cooperation in topics that are expected to be similar. Due to the u.s. importance on illicit drug cooperation, the creation of a South American Council dedicated to this specific area is crucial in order to understand the link between leadership and ideology in regional cooperation. Second, since cooperation between the u.s. and South America in security has been closely related to promoting the incursion of the military on drug trafficking, it is crucial to link regional cooperation between illicit drugs and defense. In this regard, despite the ideological convergence of the majority of the states during the studied period, the Brazilian lack of leadership in illicit drug cooperation, the closeness between Colombia and the u.s. in security cooperation and the remanences of the military leadership in internal security affairs, affected the level of regional cooperation in defense and drug trafficking.

Methodologically, this paper uses an inductive approach based on process tracing analysis of two case studies in two different topics in order to explore the causes of why cooperation has deepened in certain sectors but stagnated in others. The link between political ideologies convergence/divergence dynamics and the presence of regional leaders supporting specific agendas in Unasur concerns the empirical observation of sectoral regional cooperation in defense and policies against drug trafficking. In this regard, the paper uses primary and secondary sources, such as the examination of official documents embodied in both councils, action plans, reunion statements, and interviews.

The paper is divided in five sections. The first section discusses the theoretical dichotomy between regional integration versus regional cooperation. The following section analyzes the relation between ideology and politicization, arguing that ideology convergence or divergence becomes an important variable to understand change within the level of regional cooperation in Unasur. The third section addresses how regional leadership is also an important variable that affects regional cooperation in South America combining both variables to build a typology to explain how regional cooperation has shifted in South America. Next sections include an empirical analysis about how cooperation has changed in the South American Defense Council (scd) and the South American Council on the World Drug Problem (swdpc). The study of both councils allow us to understand the importance of leadership in the promotion of regional cooperation and how political ideology of left-wing leaders boosted the consolidation of several agreements. Most of all the empirical analysis contributes to the argumentation that a high ideological convergence does not always end into dynamic cooperation. Last section concludes.

2.Regional integration versus regional cooperation

Unasur established in its Constitutive Treaty, the objectives to promote a project of political, social and economic content. Nevertheless, the organization only functioned as a forum that promoted political and social discussions particularly fostering cooperation mainly in defense, health, infrastructure and energy issues. Thus, the concept of regional integration it is an alien concept for an organization that never developed a typical regional integration agenda.

During the early negotiations, Unasur could be seen as a result of a new momentum in the South America region, with the emerging of leftist governments particularly in Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina and Chile, reflecting a new struggle for leadership between Venezuela and Brazil. As Dabène (2012b) explains, Brazil and Venezuela emerged as key actors in South America with a different cooperation agenda, specifically in those sectors related to infrastructure and defense.

The regional context became polarized specifically in the Andean region, where the diplomatic tension between Colombia and its neighbors, particularly Venezuela and Ecuador, reached a tense moment in 2008 when Colombia bombed a guerrilla camp in Ecuadorian territory. Based on the diplomatic crisis resolution held in the xx Grupo de Río Summit in 2008 and in the Unasur’s Bariloche Head of States meeting, Unasur played a key role in promoting a common agenda and helping to prevent further diplomatic impasses between Colombia and Ecuador. More importantly, this situation required Brazil to move from its national interests and try to find common ground to establish a consensual cooperative agenda for Unasur, which marked the South American defense agenda the following years.

Following Nolte´s (2017) claims, we consider that is central to abandon the analysis anchored to the dichotomy between regional integration versus regional cooperation. Börzel (2011) argues that there are no emergence of new forms of regionalism but rather a bifurcation between regional cooperation and regional integration. With critical eyes, Nolte (2017) states that in the past too much emphasis has been placed on the regional integration side and calls for attention to the middle terrain between these opposite ends of the spectrum. We share Nolte´s (2017) concerns but we disagree with him about the idea of exploring the middle terrain, we argue that the concept that needs more attention is regional cooperation. Since Unasur has not included a traditional trade agenda and has focused on cooperation in different areas we agree with Briceño-Ruíz and Ribeiro Hoffmann (2015) that regionalism depends on Unasur’s capacity to consolidate the consensus that deepened non-trade policy cooperation.

In fact, Schmitter (2007, p. 4) defines regional cooperation processes as the ones that,

may or may not be rooted in distinctive organizations, but it always remains contingent on the voluntary, unanimous and continuous decisions of its members. Entry into and exit from such arrangements is relatively costless; “loyalty” to the region as such is (and remains) minimal.

This concept suits the reality of Unasur. Thus the main concept to analyze is regional cooperation rather than regional integration avoiding preconceptions that underestimate this type of regional dynamics. Thus the analysis of Unasur’s sectoral councils is key not only to understand how the organization has built regional cooperation in South America, but also to assess change in those patterns.

3.Ideology, politicization and regional leadershipTable 2

Politicization has been a key concept since the notions of post-hegemonic and post-neoliberal regionalism rely on ideology convergence to explain how and why regional cooperation has been promoted in Unasur. According to Hass and Schmitter (1964, p. 707) politicization is related to delegate authority to a regional organization, meaning, «that the actors seek to resolve their problems so as to upgrade common interests and, in the process, delegate more authority to the center». Dabène (2012a, p. 42) offers a

slightly different definition posing that politicization implies that actors consider economic integration as an instrument to reach political goals such as crisis resolution or consolidation of democracy (…); politicization also implies a commitment of key political actors sharing a conception of common interests, institutional building to embody common interests, and possible participation of non-state actors.

It is key to connect what Dabène (2012a) defines as politicization with the concept of ideology, given that Dabène assumes sequences in regionalism of politicization, de-politicization and re-politicization focusing on the actors determination to achieve deep economic integration that encompass collective political goals. According to Erikson and Tedin (2003, p. 64) ideology could be seen as «set of beliefs about the proper order of society and how it can be achieved». We are conscious that the definition of ideology is wide and has been widely studied. However, the concept provided considers the effect of executive power ideology in Latin American countries, expecting that moves to the right of the political spectrum increase the probability of lowering the level of cooperation in social or highly political topics such as defense. In this regard, we agree with Acharya and Johnson (2007, p. 17) that the «institutions’ form and function will, in general, reflect the nature of the cooperation problem». Moreover, as Gómez-Mera (2013) has pointed out, states in Latin America remain in control of their regional cooperative options.

We put emphasis on the role of ideology because in Latin America traditionally presidents are key players in the regional agreements game (Scartascini, 2008). Particularly during the 1990s and 2000s, many countries in the region and mainly in South America experienced party deinstitutionalization. Political competition became less structured by political parties and moved in the direction of candidate-centered movements (Sánchez-Ancochea, 2008). Thus, we argue that ideology is key to understand the political distance among the Unasur members and its effect on the regional cooperation levels as explained in table 1.

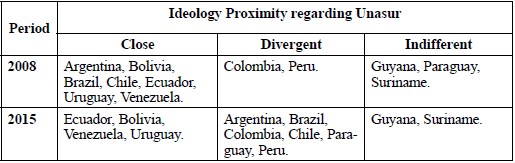

For example, in 2008 the ideological divisions in South America were the following: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay and Venezuela were leaders who had an ideological proximity with the creation and institutionalization of Unasur. Colombia and Peru, on the other hand, were not supportive of the creation and institutionalization of Unasur, while Guyana, Suriname, and Uruguay were indifferent.

During the period 2008-2015 the region experienced different changes in terms of its regional policy regarding Unasur. This ideological proximity favored the advances made since 2004 in order to materialize a regional organization with a specific agenda for South American affairs, which will experience leadership diffusion in sectoral cooperation.

According to T. V. Paul (2012, p. 5), while the larger international system is defined in terms of the interactions among major powers, a regional subsystem can similarly be defined in terms of the interactions among the key states of that region and the major power actors heavily involved in regional affairs.

Regional powers are identified not only by their relative preponderance within a given region in material terms but also by strong leadership for guiding a group of countries towards region-building and institutionalization (Godehardt and Nabers, 2011). In this sense, regional leadership can be better understood by its main functions, i.e. the delivery of public goods, the lead in regional community building schemes and support of regional organizations and the regional connection to the international system since regional powers often represent their regions in multilateral forums (Van Langenhove, Marieke, Papanagnou, 2016).

Mattli (1999, p.14) argues that a «key supply condition for successful integration is the presence of an undisputed leader among the group of countries seeking closer ties». In this view, regional integration needs two conditions to succeed: on the demand side the potential economic gains from market exchange within a region must be significant while on the supply side political leaders should be willing to accommodate the demand for integration if such moves improve their domestic conditions. However, as coordination problems are abundant the key supply condition for Mattli is that for integration to be successful there should be present a benevolent leader supporting integration.

In the case of the South American regional leadership, Brazil has been exerted it through soft power (Malamud, 2011), as a passive regional leader (Flemes, 2010) and as an articulator of regional interests in multilateral fora (Deciancio, 2016) but always using persuasion and consensus creation to pursue regional interests. Regarding Venezuela its regional leadership has been exerted in a more ideological and reactionary way opposing free market (Altmann Borbón, 2009).

According to Mattli (1999) the willingness to lead and follow depends on the payoff of integration to political leaders. In this sense, we agree with this view and argue that in order to enhance the level of regional cooperation when a leader decides to support a new regional organization is to build political consensus among members in relation to important topics for the region (Nolte, 2011). In a similar vein, Palestini and Agostinis (2015, p. 2) state, «the convergence of preferences for a course of action or policy option is a condition for the inception and progression of a regional cooperation process. But preference convergence is hardly possible without the action of a regional leader».

We explain regional cooperation or lack of it in Unasur by combining two main variables: ideological convergence/divergence in the initiative main members, and the willingness and capacity of the regional leader/s to be in charge of fostering cooperation in the initiative. We ponder the relation between regional leaders and their followers since that relation is key to understand their respective regional order (Nabers, 2010) understood in this paper as their level of cooperation.

Ideological convergence and regional leadership are supposed to be facilitators for regional cooperation in our framework. In this sense, we expect that in periods in which ideological convergence is high vis-à-vis a clear willingness and capacity to lead from the regional leaders the level of cooperation is expected to be higher than scenarios in which ideological divergence and/or lack of leadership prevail. We have organized a tentative typology -see table 3- that combines the two key variables in our framework to explain how the level of cooperation has changed in Unasur.

3.1 Leadership capacity and willingness Ideology

The relation between the type of organization and ideology is also another link to explore. Since Unasur is an organization in which predominates a political agenda vis-à-vis the weakening of the trade and economic dimensions (Sanahuja, 2009, Riggirozzi and Tussie 2012, Briceño-Ruíz and Ribeiro Hoffmann, 2015), the argument shows a relation between the ideological convergence and the type regional cooperation promoted. Right-wing neoliberal governments support regional cooperation in trade and economic liberalization topics while left-wing progressive governments have supported political and social regional cooperation.

In order to analyze the level of cooperation it is necessary to combine both variables and open up the regional cooperation box analyzing how these two variables have affected regional cooperation in different sectors.

4. Ideology and Leadership in the sdc

Studies about Unasur regional cooperation in the defense sector has been mainly focused in its ‘gradual and multidimensional’ creational process (Comini 2010, 2015, Sánchez 2017) not taking into account the maturation of several agreements that respond not only to the ideological context in South America in the 2000s, but also to changes in the geopolitical context during the 1990s and 2000s. In this regard, we aim to focus on the role that regional leaderships and ideological changes in the past 15 years within the defense sector for two main reasons. These two variables are fundamental not only to understand the levels/ cycles of cooperation in Unasur even in ‘taboo’ areas such as security and defense but it also helps us to unfold unknown cycles of convergence in regional cooperation of the 12 member states of Unasur that do not necessarily repeat in other areas.

This section intends to analyze first the creation and the institutionalization of the scd, focusing on the role of Brazil in 2008. Second, the section addresses leadership diffusion patterns of several leaders that contributed to the cooperation agenda in the scd. Finally, through the examination of official documents embodied in the scd, particularly its action plans, reunion statements and the defense ministries declarations, the last section analyzes the successes and failures of regional cooperation in the defense sector from 2008 to 2015.

The initiative to consolidate an agenda on defense is not new in South America. During the First Presidential meeting of South American Presidents in 2000, the presidents established South America as a Peace Zone, resembling the importance of both, the Andean Compromise of Peace and Security Declaration of 1989 and the 1998 Ushuaia Mercosur Declaration. Despite the initial importance of defense affairs, it was not until the VI South American Summit in 2007 to promote the cooperation in defense as a priority affair.

The Brazilian role during the creation of the scd is crucial in order to understand the scope of regional cooperation. At the beginning of 2008, the Brazilian Ministry of Defense Nelson Jobim visited the 12 ministries of Defense in South America with the objective to create, within Unasur, a forum aimed to lead to a model of cooperation in that field (Jobim, 2009). This initiative responded to the Brazilian Defense Strategy (2005) which had an important focus on reaching, through their leadership, certain degree of regional stability by consolidating regional cooperation as a tool to increment trust, but most importantly as a mechanism to expand the process of infrastructure modernization in Brazil (Jobim, 2009, Comini, 2015). In this sense, the Amazonia and the Southern Atlantic were considered as priority areas in the Brazilian aforementioned strategy. As the former Ministry of Brazil stated, in order to reach a regional agenda, concepts such as consensus, political harmony, and convergence were crucial in South America (Ministry of Defense, 2005).

It is important to highlight that the leadership of Brazil was not contentious, particularly Itamaraty -The Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs- was very cautious in fact, they aimed to lead a discrete regional leadership particularly to avoid conflicts (fes-flacso, 2010) promoting an agenda similar to the strategy posed by the u.s. in the region during the last decades. For example, since 2002, Brazil was very careful in terms of avoiding leading a strategy based on imposition of rules; instead the country opted to adapt its regional strategy towards a «flexible cooperation, without ties or automatisms» (Comini, 2015, p. 18), which went simultaneously with the advances made by the members during the construction of the Constitutive Treaty of Unasur, which characterized the organization institutional design as based on consensus and dialogue2.

The Brazilian strategy about the articulation of the South American cooperation had its central feature, in defining the issues that needed to be discussed and the working agendas (Ugarte, 2010, p. 4). This argument is rooted in the importance that Brazil posed in promoting the development of a regional defense industry and to develop mutual trust between its members. At least, both priorities were fundamental in order to accomplish the national strategy embodied in the Política de Defensa Nacional of 2005 and Brasil 3 Tempos project.

With this scope and after the lobby made by the former Minister Nelson Jobim, during the Extraordinary Summit of Heads of States of Unasur in 2008, President Lula da Silva, proposed the Creation of the scd aiming to contribute to the formation of a regional identity in defense, which considered the sub-regional characteristics articulating a vision based on mutual values and common state-to-state interests (Jobim, 2009, p. 20).

Despite the move made by Jobim, only Colombia showed some doubts during the process. For this reason, the former President of Chile, Michelle Bachelet proposed the creation of a Working Group in order to analyze the Brazilian proposal. Even with this initiative, Colombia was reluctant to participate in the regional agenda. It was not until the II meeting of the working group in 2008, that Colombia would be officially incorporated in the consolidation of the scd.

We argue that the creation of the scd is based on two main elements. First, the institutionalization of a political agreement on defense that promoted South America as a peace zone and as a base towards democratic stability in the region. Second, the need to consolidate cooperation in this sector -implicit in the ideology of left wing leaders- based on mutual trust between the South American countries against ‘foreign or external threats’, specifically those historically and ideologically represented by the u.s. influence in the region. Connected to this idea, appears the need to specify a mechanism to reduce uncertainty in the face of increased defense costs or potential doubts about the military actions of bordering countries with previous state conflicts, such as those between Peru and Ecuador, Chile and Peru, among others.

Finally, on December 16, 2008 during the II Extraordinary Summit of the Head of States of Unasur, with the consent of the twelve head of states the scd was formally established with the following objectives:

To consolidate South America as a peace zone, based on democratic stability and the integral development of our peoples, and a contribution to world peace;

To create a South American identity in defense, incorporating sub-regional and national characteristics that strengthen unity in Latin America and the Caribbean;

To generate consensus to strengthen regional cooperation on defense issues.

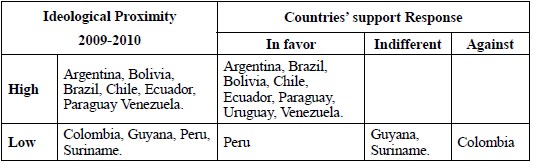

During the Unasur early years, Brazil faced a favorable scenario determined by an ideological proximity with several South American presidents, which allowed Brazil to promote a regional order based on the Brazilian way of regional cooperation in defense affairs -see table 3. It is important to highlight that the Brazilian leadership did not operate by imposition, which allowed Brazil to adopt a consensus agenda and respecting each country’s sovereignty in such a delicate topic as defense.

We highlight that leadership diffusion and politicization were key for two reasons. First, the institutionalization of Unasur establish a higher responsibility for those countries that held the Pro Tempore Presidency (ptp), setting them in charge to promote, summon, and preside the Council’s meetings. Second, since 2008 to 2015, the trend derived from the sdc Action Plans show that the countries who are in charge of the ptp, take more responsibilities of a higher number of activities in comparison with those countries that do not. Thus, those countries that hold the ptp, control the cooperation agenda for one year, which means that cooperation cycles are determined by the country’s capacity in focusing its agenda in promoting regional cooperation in Unasur3. This argument explains the willingness of similar ideological countries’ that hold ptps, such as Argentina and Ecuador, to promote remarkable advances in the defense cooperation.

The difficulties of a country to lead sectoral cooperation meetings and activities had negative consequences on regional cooperation in Unasur. These difficulties were related to the country lack of resources, language barriers and institutional divergences. Few examples in this sense could be explained during the Guyana and Suriname ptps, as both countries found hard to carry out the meetings, discuss the activities, and lead Unasur during the period 2010-2011 and 2013-2014 respectively.

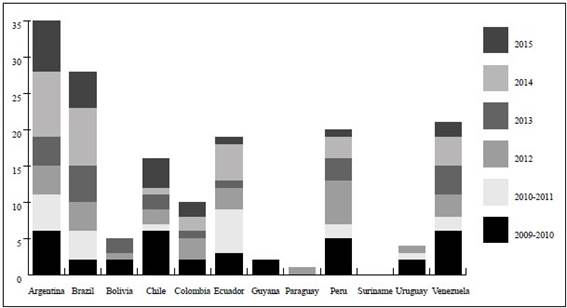

Taking into account the information based on the Action Plans we identified two countries that challenged the Brazilian leadership in the scd. Argentina and Venezuela4 were also very active members presenting action plans in the sdc -see graph 1.

Source: Own elaboration

Graph 1: Action Plans of the scd/Number of activities by countries: 2009-2015

Argentina was the most active country in the scd from 2008 to 2015. First, during the Kirchner administration, the country maintained an active participation and a high political will of Nestor Kirchner that help to promote the importance of Unasur, this situation was exacerbated when Kirchner became Unasur Secretary General. Moreover, the ideological closeness of Argentina’s president Fernández de Kirchner with the governments of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela motivated an active participation in the organization. The political support allowed the different Ministries of Defense, to focus its cooperation on Unasur. Second, the continuity of Alfredo Forti as part of the Argentinean delegation in the scd, first as Secretary of Foreign Affairs in the Ministry of Defense, following as Vice Ministry of Defense and finally as Director of the Strategic Centre of Defense allowed Argentina to promote its policies in South America (Comini 2015).

Since 2008 Argentina -despite the importance of Mercosur for the country- saw the opportunity to take advantage of the Brazilian strategy in Unasur (Comini, 2010). During the internal discussions carried out in the Ministry of Defense of Argentina in October 2009, the participants highlighted the importance of knowledge production and military cooperation, but most of all agreed that Brazilian aspiration of searching for a potential market of its defense industry could constitute an important vehicle for the construction of common interests among the scd (Comini 2010). It was also argued that the scd, despite its lack of institutional framework and commitments, could constitute an adequate deterrent mechanism regarding hypothetical interventions of non-South American countries in the region. This circumstance derived from the fact that a country that could be attacked could require a scd meeting in order to agree on measures against such intervention (Ugarte, 2010, p. 8).

Since 2008 Argentina was highly active in promoting a South American Centre of Studies of Defense. In 2010, Argentina presented the project at the Ministries meeting, offering infrastructure and specific budget in order to accomplish the activity. The Centre was founded in 2012, and it was an important step towards the consolidation of South American knowledge diffusion in defense, but most importantly it -constituted a permanent institution of Unasur- focusing on identifying the regional interests based on the national interests of Unasur members (ceed, 2018). The Argentinean contribution to the scd allowed countries to access relevant studies focused on military expenditures and most of all it allowed Unasur members to carry virtual meetings.

In the case of Venezuela, and particularly since Chávez assumed the presidency, the country had an active role in promoting the integration of the armed forces in South America. In 2001, the country promoted the sovereignty of defense through political integration based on the Patria Grande Bolivarian philosophy. Due to this strategy, in 2006 the former president Chávez presented his idea of a security alliance to the Presidents of Mercosur, arguing the need to create a mechanism similar as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. In this sense, Hugo Chávez showed his intentions of promoting its leadership by counterbalancing the power of the u.s. in the region.

With Brazil as a leader promoting the ideals of the sdc, Venezuela endorsed during the negotiation of the Working Group of Defense in 2009 the creation of an structure based on the unification of the military forces and a geopolitical block with the capacity to act jointly in case of threat related to defense (Donadio, 2010). The document, despite its ambitions, agreed with the Brazilian proposal in developing a South American defense identity (Comini, 2015).

Despite the Venezuelan proposal, the countries were reluctant to accept the proposal as part of the scd. Nevertheless, Venezuela continued implementing its vision by promoting a South American Defense Doctrine through the promotion of seminars and workshops embodied in the Action Plans activities, such as the «identification of conceptual approaches to defense» or the «identification of risk factors and threats that affect regional and world peace». They were also very active in promoting measures of mutual trust in Unasur through the common analysis and response towards the «u.s. White Book on Air Mobility» (El Comercio, 2010). As Graph 1 shows, Venezuela was the third country behind Argentina and Brazil in leading activities in the scd, especially in those related to military operations and doctrine-building.

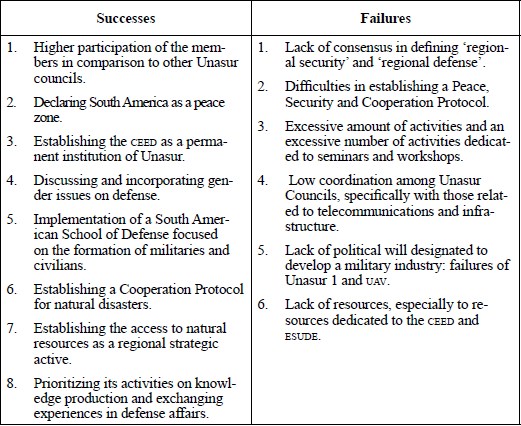

Despite its institutional ‘limitation’ in terms of decision-making, the Council has focused its attention on building technical expertise, superior information, and to some extent, the Council has shown an adaptive flexibility. Several examples could be described in building technical expertise and further institutionalization in defense affairs, such as the implementation of the Center of Defense Strategic Studies, the creation of the South American School of Defense (esude), the materialization of seminars and conferences based on common risks, and, finally, the creation of an Executive Secretariat (Vaz, Fuccile, and Pereira, 2017). Moreover, the Council has paid special attention to seminars and workshops dedicated to share experiences and to build a common knowledge on defense affairs. Moreover, the Council has orderly cooperated among five topics: Defense policymaking; military cooperation; humanitarian action and peace cooperation; defense industry and technology; training and qualification and finally a topic related to mutual-trust building.

The adaptive flexibility brought some convergences and divergences especially in discussing topics that are not necessarily incorporated in the field of defense, such as arguing by request of Colombia the role of Armed Forces against Transnational Organized Crime and the war against drugs.5 Since the Statute does not include any restrictions besides the Council’s objectives, the Unasur members had the possibility to include any activity as long as they assume the responsibility to lead it. Thus, during the first years, the activities were too broad and difficult to render, however in 2011, the csd decided to create a Working Group in charge of «elaborating a methodology which allows the states to optimize the activities embodied in the Action Plans». The initiative -despite the methodology by the Working Group was just implemented since 2015- resulted in an improvement of the Action Plan’s compliance from around 25 % in 2010 of its activities to 86 % by the end of 2015.

Based on the Venezuelan idea of promoting a South American doctrine of defense, member states discussed interpretations of national security and the scope of regional defense, nonetheless during several seminars and workshops dedicated to this topic, the members showed difficulties to agree on a regional concept of national security and regional defense demonstrating that those topics are among the most critical issues of regional cooperation that still need to be addressed.6

Finally, the scd showed serious difficulties to accomplish an effective mechanism to cooperate on improving the industrial capacities of defense. Even though, Brazil focused on the importance of developing the industry and technology related to defense, the strategy failed in achieving those activities related to build a South American Unmanned Aerial Vehicle -uav- and the Argentinean proposal to create a regional training aircraft known as Unasur 1. The analysis of the action plans and official documents of the scd since its creation, shows in table 4 the following successes and failures of the Council during the period 2008-2015:

The previous analysis shows the importance of leadership in the promotion or diffusion of regional cooperation and how the political ideology of left-wing leaders boosted the consolidation of several agreements and the creation of institutions related to defense topics within Unasur being the Strategic Centre of Defense Studies and the South American School of Defense the most prominent examples.

It is important to highlight the contrast between the results that this council achieved with the meager results that the World Drug Problem Council obtained in the same period and under the same circumstances of leadership and ideological convergence.

5. Ideology and Leadership in the swdpc

This section addresses cooperation focusing on the swdpc. We chose this sector because even though it is supposed to be a topic close to defense, the pattern of cooperation is quite different, mainly due to the incompatibility of several countries to encourage an alternative solution to the world drug problem, while at the same time at the domestic level those same countries promote punitive laws and repressive practices (Tokatlian and Comini 2016). Unlike the positive contrast of the defense sector, the South American states showed incompatible strategies to achieve a high level of regional cooperation on drug trafficking. The domestic policies regarding drugs, the limited domestic consensus, the low ideological response in order to promote a ‘common agenda’, led the Council’s objective into a gridlock.

In comparison to the sdc, the absence of a Brazilian leadership in this topic was determinant to hinder a regional cooperation agenda based on drug trafficking. However, Ecuador tried to act as a regional leader during this Council’s consolidation based on two initiatives: the initial motivation of the Ecuadorian government during its ptp of creating a mechanism focused on the coordination and complementation of actions against criminal organizations dedicated to drug trafficking. Second, raising the need to build a South American doctrine that separates the duties of internal security, specifically in those areas where the internal security forces lost their domain.

This section first analyses the initial motivations that contributed to the creation of the swdpc and the emergence of Ecuador as a leader on drug trafficking cooperation during the Council’s creation. Second, through the examination of official documents and interviews, the section addresses the reasons behind the failure of South American cooperation in drug issues during the period 2010-2015. These objectives help us to elucidate the difficulties to lead a regional agenda in drug policies and contributes to the argumentation that a high ideological convergence does not always leads to dynamic cooperation.

The fight against drugs during the 1990s became one of the most controversial agendas in South America. Due to the promotion of the 'war on drugs' in the late 1980s, the u.s. substantially increased its presence by cooperating with the armed and police forces, through the donation of equipment, armament and technical assistance. The objective was to eliminate the drug supply destined to the u.s., having as an immediate consequence, the securitization7 of drug trafficking as the main threat to national security. Cooperation with the u.s. had consequences in domestic disputes between the police and the armed forces about which force receive the resources coming from the u.s. Moreover, the u.s. assistance marked the adoption of specific institutions, which had the possibility to propose laws aimed to increase penalties for illegal drug trafficking and consumption.

At the political level, these activities and the financing and presence of the u.s. in the military and police forces were a central point of discussion between left and right wing governments. Particularly, that presence served as a political strategy that imply a discourse of a loss of sovereignty, due to the installation of u.s. Forward Operating Location (fol) in Manta, Ecuador. In fact, in 2009 the Correa government decided to end the 10 year agreement with the u.s. in Manta, arguing the sovereign decision of Ecuador to reject external military bases on their territory. During the first decade of the 2000s, several countries such as Argentina, Bolivia and Venezuela had a negative perspective about the role of the u.s. in the region, due to the increase of military bases in Colombia and the transformation of the Colombian armed forces into specific actions to prosecute domestic crimes, a task normally attributed to the police.

In fact, during 2008 and 2009 the presidents of Unasur highlight their concerns about the u.s.-Colombian military relation, showing the regional disgust towards the instauration of u.s. military bases in Colombia. Due to this discontent, Uribe started a «Silent Tour» in August 2009 in order to explain the reach of the u.s.-Colombian military cooperation. Despite the maneuver, only the governments of Paraguay and Peru argued the Colombian sovereign decision to cooperate with the u.s. (Sánchez, 2017).

In this sense, during the II Extraordinary Meeting of Heads of State held in August 2009, the Presidents of Unasur, motivated by the need to establish cooperation mechanisms to strengthen sovereignty, integrity, and inviolability of their states, instructed «to elaborate a statute and an Action Plan with the objective to define a South American strategy against illicit drug trafficking and strengthening cooperation among the specialized units».8 A month later, the government of Uribe signed the «u.s.-Colombia Defense Cooperation Agreement» generating a negative response from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela. In fact, the Brazilian chancellor Celso Amorim argued that «the fight against drug trafficking as something that we have to fight without external interference» (Sánchez, 2017).

Despite the South American discontent towards the u.s. military presence in Colombia, those same counties did not find a feasible strategy to generate an effective mechanism to counter-balance the u.s. power in the region. While Brazil and Chile also expressed their concern in this topic, there was also a historical dispersion in the region regarding this topic (Tokatlian and Comini 2016). Given that this agreement questioned the process of defense cooperation that Unasur embodied, Brazilian diplomacy itself considered tackling the issue within the framework of the cds (Comini, 2009; Iglesias, 2010, Verdes-Montenegro 2018).

Due to the Brazilian absence in promoting a drug trafficking cooperation, Ecuador as Pro Tempore President, saw the opportunity to define a South American security doctrine through the Council’s objectives. During 2009-2010, the Ecuadorian government prioritized the South American cooperation as an opportunity to consolidate a regional consensus against external threats and more specifically, as a chance to reduce the external dependency on the u.s. The Ecuadorian strategy during these years in the areas of security and defense was «to clarify the South American security doctrine and its attributions based on the specific duties of the police against drug trafficking, but most importantly to eliminate the corporatist model of the Armed Forces, especially on those issues related to the war against drugs».9

In 2009 and 2010, Ecuador aimed to lead the swdpc by promoting several activities focused on proposing a Statute focused on the fight against drug trafficking and promoting information sharing between the Drug Enforcement agencies. In order to achieve this end, the Ministry of Government and Police of Ecuador lobbied with those states who had ideological proximity in order to establish the Statute based on their interests.10 Moreover, Ecuador saw the opportunity to strengthen civilian leadership in this topic similarly to what have been done in the scd.

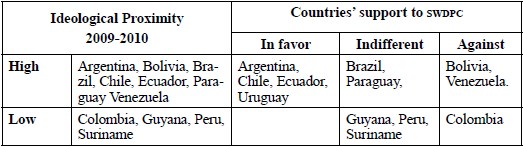

During the initial negotiations, Ecuador received the support of Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, countries with an ideological proximity at that moment, but mainly because those countries had constitutional mandates -mainly Chile- to reduce armed forces duties to the minimum including in drug trafficking issues. However, the decision to establish specific cooperation mechanisms to combat drug trafficking generated dissatisfaction in several South American countries. The most notable case opposing the creation of a specific council outside the sphere of action of the armed forces was Colombia, due to its military structure and its cooperation history with the u.s.

Although Colombia's strategy was evident due to its cooperation commitments with the u.s., during the I Vice-Ministerial meeting of the South American Fight Against Drug Trafficking Council, several Unasur countries showed serious divergences for establishing a specific council on this matter - outside the domain of the military forces -focused on dealing with specific issues to combat drug trafficking and organized crime based on attributions of national police forces. According to the former Vice Minister of Government of Ecuador,

(…); during the negotiations, we expected to count with the support of those governments with whom Ecuador had a close ideological proximity, however at the time of negotiating the statute, Venezuela and Bolivia showed a negative response towards the establishment of a cooperation agenda that recognizes the exclusivity of the police in their fight against illegal drug trafficking. (Interview to Dr. Fredy Rivera Vélez, July 7th, 2018)

Despite that Ecuador had a strong ideological proximity with Venezuela and Bolivia, the negotiations on drug trafficking showed the need to adapt the agenda in order to include recommendations of some countries, such as issues of consumption, administration, control and especially prevention of drugs based on public health policies. The following chart combines ideological proximity of South American countries to cooperate on the Ecuadorian proposal on drug trafficking: (Table 5)

Due to the opposition of Bolivia and Venezuela, and the passive participation of Brazil during the negotiations, during the xxiv meeting of the Delegates Council in April 2010 the states agree to change the denomination to the swdpc, arguing that there was a need to line up regional cooperation on drug affairs with the oas -cicad- United Nations cooperation agenda incorporating aspects related to public health and alternative development policies.

In this sense, in April 2010, the swdpc was formally established with the following objectives:

To propose strategies, plans and coordination and cooperation mechanisms between the members in order to influence an integral impact on all areas of the problem;

To create a South American identity to face the world drug problems, taking into account international commitments in this matter, as well as the national and sub-regional characteristics that strengthen the unity of South America;

To strengthen friendship and trust through inter-institutional cooperation between the specialized agencies of each country, to address the world drug problem through the promotion of dialogue;

To promote the articulation of consensus in multilateral forums on drugs, based on Article 14 of the Constitutive Treaty of Unasur.

The cooperation agenda on drugs started to pitfall given the negativity of some countries in stating an agreement on this issue and furthermore with the reevaluation of the Council’s objectives. Unlike the leadership evidenced in the South American Defense Council, Ecuador did not manage to consolidate a noticeable leadership during the maturation of the Council. This negativity led to reevaluate the Council's objectives according to the issues previously implemented by the u.s. in organizations such as the oas. Although the issues addressed in both mechanisms are similar, the drug policies in Unasur are framed within an ad-hoc11 institutional baggage with privileged autonomy in drug-policy building. These institutions managed to generate significant internal pressure in order to control previously established areas by the u.s.

Since its formalization, the cooperation agenda on drug policies did not achieve its goals during the five-year period analysis for the following reasons. First, according to the General Secretariat of Unasur (Unasur, 2012) during the first two years, the council’s debate was focused on the elaboration of the rules of procedure and the scope of the council. If we compare cooperation in drug trafficking with other agendas, the swdpc has made little or none agreements during the first two years, which made difficult for some states to motivate new agreements.

Second, and as a consequence of the lower materialization of agreements, the Ministries of the members did not give sufficient attention to the Council’s meetings. For example, from 2010 to 2015 the Council barely met in five occasions, and one of them in 2012, could not make any agreements due to the fact that only five countries participated. Third, during the five year under analysis, the number of agreements, the implementation of a five year Action Plan with low responsibilities, and most of all the low political interest to comply with the agreement, made several states think that the council was destined to fail or to make small contributions outside the agenda implemented in the oas. For example, the General Secretariat reported in 2012 (Unasur, 2012) that during the first two years the council achieved two agreements: the elaboration of the Action Plan and the consolidation of a mechanism which aimed to create an information sharing platform among the judicial, police and financial areas. Moreover, the states agree about the necessity to create a South American Observatory of Drugs; nevertheless during the period 2010-2015, the task was not accomplished.

From 2010 to 2013, the documentation showed a lack of institutional support from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, even in those countries were the ideological proximity with Unasur were high. During the Council’s meetings of Unasur, the participation of the embassies have proved to be unsuccessful, due to the detailed knowledge of the activities carried out during the meetings. According to the official documentation, this is due to a low internal communication between the Ministries in charge of drugs and the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and vice versa.

In addition, the leadership of Ecuador in this topic lost continuity after the change in the Council’s objectives in 2010. From this year on, there was no continuity to prioritize this agenda from the Ministry of Interior and the Drugs Secretariat, who were in charge of the subject. This is due to changes in authorities and a consequent 'conceptual chaos' to delimit the actions of internal security and citizen security. Within the shortcomings in this issue, given the need of Colombia to generate an external space that addresses subjects of organized crime, the result of these actions generated serious confusion in the agendas and fundamentally, an overlap of activities between councils. Given the low acceptance of South American countries to include drug trafficking within the agenda of the Defense Council, in 2011 Colombia required establishing a mechanism that provide representativeness and allow actions at the regional level given their internal conflict. The result of this maneuver was the creation of the Council for Citizen Security, Justice and Coordination of actions against Transnational Organized Crime, which propose «to combine its tasks with the South American Council on the World Drug Problem». In sum, both councils destiny were similar, a low cooperation agenda given the complexity, overlapping and confusion of the members to comply with the proposed activities by similar councils.

Finally, the swdpc reflects the difficulty to line up the ideological convergence with internal institutional practices inherited by the u.s., domestic institutions that address issues of drug trafficking based on the objectives established in the framework of cicad, found extremely difficult in practice to propose specific objectives to fight drug trafficking without the participation and information access of the u.s.

6. Conclusion

The logic of the argument is straightforward; it first incorporates the ideological context in order to disentangle the indirect influence of ideologies in terms of regional cooperation. The analysis of political ideologies convergence/divergence dynamics in the South American context provides supplementary inputs regarding the persistent variance found in levels of cooperation. Especially if considering that «societal demand is hardly sufficient, it takes political leadership and international institutions to propel regionalism» (Börzel, 2011, p. 17).

Second, we argue that regional leaders are entrepreneurs who used the power of ideas in order to help state preferences and interests converge. As Nabers (2010, p. 51) points out «leadership is effective and sustainable when foreign elites acknowledge the leaders’ vision of international order and internalize it as their own». In this sense, regional leadership is exercised through the construction of political consensus among members in relation to important topics for the region, particularly to enhance regional cooperation.

The two sectoral cases studied in this paper showed that a context of ideological convergence is a necessary but not sufficient condition to enhance regional cooperation. As it was explained the combination of ideological convergence vis-à-vis a strong regional leadership supporting the agenda of the sdc and enhancing consensus among members made a deep level of cooperation possible in this topic. Moreover, the alternation in leading this topic by other countries support such as Argentina and Venezuela made cooperation in defense possible even in times in which Brazil hesitated. On the contrary, the swdpc case show that even though there was an important ideological convergence among members the sectoral agenda in this topic did not flourish given that there were not regional leaders engage in the promotion of this topic. Despite Ecuador efforts to act a leader promoting this agenda the Council faced many resistances from other members even with ideological proximity to Ecuador. This resistance given the overlapping of initiatives in this sense in other organizations such as the oas impeded to advance cooperation in the fight to drug trafficking.

Even though we have analyzed regional cooperation patterns in two sectors during the period 2008-2015, the current critical situation of Unasur showed that a certain level of ideological convergence was a necessary condition to guarantee cooperation, particularly for an organization in which a highly political agenda of cooperation prevailed. In contrast to regional integration initiatives in which stagnation can be tolerated for long periods, Unasur showed that since most of its commitments were related to highly important political issues the change in the ideology of some of the most important members generated first an impasse in the election of the Secretary General followed by the abandonment of the institution of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay and Peru. As we argued at the beginning of the paper ideological convergence was important to explain cooperation patterns as many authors related to the post-neoliberal post-hegemonic debates have argued but in order to achieve higher levels of integration leadership of different countries encouraging sectoral agendas were key to foster high levels of cooperation.