Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política

On-line version ISSN 1688-499X

Rev. Urug. Cienc. Polít. vol.23 no.spe Montevideo Dec. 2014

WOMEN’S REPRESENTATION AND LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE APPOINTMENTS: THE CASE OF THE ARGENTINE PROVINCES*

Representación de las mujeres y designaciones a comisiones legislativas: El caso de las provincias argentinas

Tiffany D. Barnes**

Abstract. Over the last two decades a large number of countries worldwide have adopted a gender quota to increase women’s political representation in the legislature. While quotas are designed to improve women’s representation in legislative positions, it is unclear if electing more women to legislative office is sufficient to accomplish institutional incorporation. Once women are elected to office, are they being incorporated into the legislative body and gaining their own political power, or are they being marginalized?Using an original data set that tracks committee appointments in the twenty-two Argentine legislative chambers over an eighteen-year period (from 1992-2009), I evaluate the extent to which women have access to powerful committee appointments –beyond traditional women’s domains committees– andhow women’s access to committee appointments changes over time. I hypothesize that while women may initially be sidelined, as they gain more experience in the legislature they may overcome institutional barriers and develop institutional knowledge that will better equip them to work within the system to gain access to valuable committee appointments.

Keywords. Argentina, provincial legislatures, women, committees

Resumen. Durante las últimas dos décadas un gran número de países en todo el mundo ha adoptado cuotas de género para aumentar la representación política de las mujeres en las legislaturas. Mientras que las cuotas son diseñadas para mejorar la representación femenina en puestos legislativos, no está claro si el acceso de más mujeres a cargos electivos es suficiente para lograr su incorporación institucional. Una vez que las mujeres son electas al cargo, ¿se incorporan al cuerpo legislativo y ganan poder político propio, o quedan marginadas? Utilizando un conjunto original de datos que mapealos nombramientos a las comisiones en las 22 legislaturas provinciales argentinas durante un período de 18 años (1992-2009), evalúo el grado en que las mujeres han tenido acceso a las comisiones poderosas –más allá de las comisiones tradicionalmente vistas como dominio de las mujeres– y cómo el acceso de las mujeres a designaciones a las comisiones cambia a lo largo del tiempo. Manejo la hipótesis de que mientras que es posible que las mujeres inicialmente sean marginadas, en la medida que adquieran más experiencia en la legislatura podrían superar las barreras institucionales y desarrollar un conocimiento institucional que las prepara mejor para trabajar dentro del sistema para acceder a nombramientos a comisiones consideradas valiosas.

Palabras clave. Argentina, legislaturas provinciales, mujeres, comisiones

1.Introduction

In the past three decades, governments around the world have taken measures to increase women’s numeric representation in legislative bodies. Of particular interest, over a hundred countries worldwide have adopted some form of gender quota to increase women’s access to legislative influence.Quotas are designed to increase women’s numeric representation, yet it is unclear if electing more women to legislative office is sufficient to accomplish institutional incorporation. In particular, extant research indicates that women are not attaining influential political appointments such as powerful committee posts at the same rate as their male counterparts (Heath, Schwindt-Bayer, and Taylor-Robinson 2005; Schwindt-Bayer 2010). Once women are elected to office, are they being incorporated into the legislative power structure and achieving influence,or are they being marginalized?

I argue that, as newcomers, womenentering into male-dominated legislative arenasmay face structural barriers that limit their access to valuable resources, such as powerful committee appointments, within the legislatures. But as women gain more experience in the legislatures, they may overcome these barriers and develop institutional knowledge that will better equip them to work within the system to gain access to these resources. Thus, I hypothesize that increases in numeric representation may initially result in a marginalization of female legislators, but over time women’s access to powerful appointments will increase. To evaluate this hypothesis I examine women’s appointments to prestigious committee appointments in twenty-two subnational Argentine legislative chambers from 1992 to 2009.

In doing so, my research makes three contributions to the literature on women’s legislative appointments.First, it moves beyond previous research that considers women’s access to legislative appointments and how they change, based on the composition of the legislature, to develop theoretical expectations forhow women’s access to valuable legislative appointments change over time, as numeric representation becomes more institutionalized in the legislature. Second, I test my hypotheses using an original subnational data set that allows me to examine legislative committee appointments over a large number of chambers and a long period of time. Finally, I provide strong empirical support for my theoretical expectations, which have important implications for understanding how women’s access to legislative committee appointments changes as women learn to navigate the legislative arena.

2. Women and legislative committee appointments

Over the last few decades, women have gained access to legislatures across the globe in record proportions (IPU 2012). Still, the question remains:once women are in office, are they fully incorporated into the decision-making process, or are they excluded from important positions of power?Some research addressing this question finds evidence that women are less likely than men to receive powerful committee appointments, but other studies find evidence to suggest that women are not disadvantaged in their committee appointments.

Research that finds evidence of gender differences in committee assignments often shows that women are less likely to receive powerful committee posts (“powerful committees” vary depending on the context but often include economy, finance, or agriculture) and more likely to receive appointments to “social issue” committees or committeeswith stereotypically feminine issue domains(e.g., culture, education, health care, human rights, and family and youth) (Heath, Schwindt-Bayer and Taylor-Robinson2005; Kerevel and Atkeson 2013; Schwindt-Bayer 2010; Thomas 1994; Towns 2003). These results lead some scholars to conclude that women are being marginalized in the legislatures and do not have the same opportunities as men to sit on powerful committees (Heath, Schwindt-Bayer and Taylor-Robinson 2005).Nonetheless, studies that look at legislators’ preferences in congruence with their committee appointments find that differences in committee assignments often reflect women’s preferences or a combination of preferences and discrimination.For example, studies from the United States Congressand Danish local councils find that gender differences in committee assignments are consistent with legislators’ preferences and are unlikely to be a product of discrimination (Bækgaard and Kjaer 2012; Thomas 1994). In the case of Latin America, Schwindt-Bayer (2010) determinesthat women’s overrepresentation on social issue committees is consistent with legislators’ preferences, yet women’s underrepresentation onpowerful committees and more stereotypically masculine domain areas is not consistent with legislators’ preferences and thus can be attributed to discrimination.

Still, gender differences in committee assignments are not universal. Research fromGreat Britain, Mexico, Scotland, Sweden, and Walesdoes not find systematic gender differences in committee assignments (Brown et al. 2002; Kerevel and Atkeson 2013; O’Brien 2012). For example, in the case of select committees in the British House of Commons, O’Brien (2012) finds that women and men have the same likelihood of obtaining select committee appointments.[1]Moreover, she demonstrates that women may actually be advantaged in intraparty elections for select committee chair appointments. Similarly in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies, Kerevel and Atkeson (2013) show that women are less likely to be appointed to economic committees but are not less likely to be appointed to other powerful committees or to hold committee chair positions. Also, in the case of Costa Rica, Funk, Morales and Taylor-Robinson (2014)report that women and men hold an equal number of committee chair positions.

Extant research has made significant contributions to our understanding of women’s ability to gain access to powerful committee appointments. Several questions remain unexplored, however. In particular, few studies make cross-chamber comparisons, comparisons over a significant duration of time, or direct comparisons from before and after the adoption of gender quotas.[2] These limitations make it difficult to understand how factors such asthe adoption of quotas orchanges innumeric representationinfluence women’s appointments and how this changes over time.I have designed my research to address directly the influence of these factors.

3. Gender quotas, numeric representation, and access to powerful appointments

A large body of research demonstrates that the implementation of quotas is a fast-track method for increasing numeric representation(Jones 2009; Schwindt-Bayer 2009; Thames and Williams 2013).Despite providing women access to the legislative arena, the adoption of gender quotas (Schwindt-Bayer 2010) and increases in numeric representation (Heath, Schwindt-Bayer, and Taylor-Robinson 2005)have oftenresulted in the marginalization of women within the legislative chamber. Indeed, research has articulated a number of reasons why the adoption of gender quotas and sharp increases in numeric representation may result in limited access to valuable legislative appointments among female legislators. Nonetheless, there is also reason to believe that women’s access to powerful appointments in the legislature may improve overtime (Beckwith 2007; Grey 2006). I drawing on previous research, I articulate why women may have less influence in the legislature when they are newcomers. Then, I develop an explanation for why women’s access to powerful positions may increase over time, as numeric representation becomes institutionalized in the legislative chamber.

I use interviews with female legislators from the Argentine provinces to illustrate the ideas developed in this section. The interviews were conducted during fieldwork in Argentina in June and July 2013. During this time I traveled to Mendoza, Entre Ríos, Salta, and the Federal District. I conducted 27 interviews with female legislators and other elite political observers. The interviews are out of sample interviews because they took place after the period analyzed here. I used snowball sampling to obtain interviews. It is possible, or even likely, that other legislators not interviewed have different perceptions and experiences than those expressed here. Regardless, this is not problematic for my theory or analysis because the interviews are not used to develop theory or to test hypotheses. Instead the interviews are used to exemplify the ideas advanced in this section.

3.1.Women as newcomers: limited access to powerful appointments

For multiple reasons, the implementation of gender quotas combined with sizable increases in numeric representation could result in marginalization of female representatives or backlash from male legislators, both of which may ultimately limit women’s influence and access to powerful appointments in office (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, Schwindt-Bayer 2010). One reason for this concern is that quotas reserve positions for women on the electoral ballot or in the legislative chamber, and as a result male legislators (the traditionally dominant group) mayfeel threatened by the newcomers, fearing that female legislators will demand and occupy scarce resources. This point is illustrated by a female deputy’s observation that men occupy the majority of powerful positions in the Salta Chamber of Deputies. She notes that among men “there may be a fear that they will lose their positions, because for women to gain these positions, men have to lose them.”[3]Male legislators may thereforerespond by bypassing women for powerful political appointments in an effort to preserve power for themselves (Bauer and Britton 2006; Beckwith 2007; Zetterberg 2008). Schwindt-Bayer (2010) finds some support for this phenomenon. In the case of the Argentine National Congress, for example, she finds that women’s access to powerful committee appointments declined after the adoption of gender quotas.[4]

In addition to backlashfrom male legislators, women may face other structural barriers that initially limit their access to valuable political appointments. A second reason women may not receive appointments to powerful committees is that, asnewcomers, female legislators may have less experience in these policy or “thematic”areas and therefore may not be chosen for and/or may not choose to pursue appointments on these committees. For example, when describing the first legislative session after the implementation of gender quotas in Entre Ríos, a female deputy observes that female legislators from Entre Ríos are practically absent from the budget committee. From her point of view, however, this is not because men are excluding them from positions of power; rather, she suggests that women do not pursue these positions. She explains, “in general, women in the chamber are not involved in issue areas dealing with numbers. We do not approach these issues, and men do. Maybe it is also because this is the first time we were ever elected.This is the first time we have studied the provincial budget. It is probably one of the toughest themes to study. That is why women are not associated with the numeric themes.”[5] If her reasoning is correct, when women are new to the legislative system they may be underrepresented in powerful committees such as the budget committee, but as they develop policy expertise in these thematic areas they may feel more confidentabout pursuing appointments and serving on powerful committees that require more technical knowledge.

A third, related reason why women may not initially receive valuable appointments is that when gender quotas are first adopted, women, like any group of newcomers (see, for example, Fenno 1997) may lack the practical and political skills (such as familiarity with formal legislative rules and more subtle norms) necessary to successfullynavigate the legislative arena, which is essential for obtaining valuable committee appointments (Franceschet and Krook 2008).Gender quotas typically lead to a sudden increase in the number of women in office. It is likely that the majority of these women do not initially have the legislative experience required to accomplish their goals and maneuver within the legislative arena. As a result, they may not be assigned to powerful committee appointments and instead may be relegated to committees focused on traditional women’s issues or social issues. In the first session after the adoption of gender quotas in Entre Ríos, a female deputyprovidedthe following account:“There are women who are legislators for the first time. Meanwhile, there are men who have been deputies or senators before. They have been trained. They know what they have to do to achieve their goals… We [women] are still learning, we do not know yet, it is all a practice.”[6] To achieve goals such as obtaining powerful committee appointments, women must first learn how to operate within the rules and norms of legislature.

Fourth, women who do want to serve on more powerful and/or stereotypically masculine committees may be less inclined than men to ask for the committee appointments they want.Females are typically socialized from a young age to be communal, nurturing, and “other-oriented,” focusing not on their own needs but on the needs of others (Eagly 1995, 1987). Males, by contrast, are taught to be assertive, dominant, decisive, ambitious, and “self-oriented” (Eagly 1987; Heilman 1995).While men are taught to negotiate, women are taught “nice girls don’t ask” (Babcock and Laschever 2007, 68). Business and academia are rich with anecdotes of women avoiding negotiation and not asking for what they want (e.g., Babcock and Laschever 2007); and there is no doubt that gender roles alsoinfluence women’s ability to obtain desirable positions in the legislature.In the Federal District,a female deputydescribes an environment in which men are more willing to speak up and demand the committee appointments they desire and women are more timid and hesitant to make demands.[7]If women are not speaking up and asking for the appointments they want or think they deserve, it is easy for the dominant group to hoard valuable committee appointments while shunting women onto social issues committees.

Taken together, this discussion illustrates a number of reasons why women, as newcomers, may not receive valuable appointments within the legislature. This is important because it suggests that women do not have the same opportunities as men to influence policy decisions that are made in powerful committees. But, as I discuss in the following section, over time female legislators may learn to navigate the legislative process and overcome some structural barriers, thus facilitating access to more powerful appointments.

3.2.Increased access to powerful appointments

The adoption of gender quotas and steep increases in numeric representation may trigger the initial marginalization of women in the legislature; nevertheless, there is reason to believe this may change overtime (Beckwith 2007; Grey 2006). As numeric representation becomes entrenched in the legislature and women establish their position in the chamber, they may make lasting gains for a number of reasons.

First, by increasing women’s presence in the legislature, over time gender quotas may cause perceptions and stereotypes about women’s role in politics to change.Formal rules, such as gender quotas, are not sufficient to change attitudes towards female politicians, but as Kittilson (2005, 643–44) explains, “formal rules and informal cultural norms mutually reinforce each other. In this way, gender quota policies can act as mechanisms for bringing women immediate gains in parliamentary seats, and can also reshape attitudes, values, and ideas towards women’s roles in politics.” When people see women in politics, their ideas about women’s role in society may begin to change, and they may view women as more capable political leaders. As such, even where the adoption of gender quotas results in immediate male backlash, over timeit may result in changes in attitudes towards women’s representation. When reflecting on how the chamber has changed since the adoption of gender quotas in Mendoza,a female deputyexplains, “Little by little, we have been winning[men’srespect…] There are very small and subtle changes […].Women have also noticed it in the kind of work they do. Now, they combine gender work with the other more technical profile, such as social, financial, cultural, or legal.”[8] Her comments illustrate that as people’s attitudes towards women’s role in politics change, women have more opportunities to legislate over a broader number of themes. While increasing numeric representation is not sufficient to change everyone’s attitude, increases in numeric representation combined with other changes, some of which I discuss below, may result in more political power among female legislators.

Second, as women gain more experience in the legislature, they will overcome institutional barriers and develop technical and institutional knowledge that will better equip them to work within the legislature to accomplish their goals. Advances in women’s ability to navigate the legislature should not be limited to women with legislative experience. Rather, senior female legislators are likely to mentor newcomers and teach them how work within the system to accomplish their goals. As such, information about overcoming institutional barriers may be transmitted to new cohorts of women.Indeed, extant research on female leadership indicates that women are more likely than men to mentor and support junior colleagues (Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, and van Engen2003). For example,a female senator from Mendoza explains, “I believe that you need to understand the dynamics and get to know the practical rules of a place. When I started, it was the other women who taught me and guided me.… I had been a deputy, and not a senator. It is a different dynamic, even though I know the rules, it has a different rhythm, a different way of interacting with the opposition.”[9] Guidance from her female colleagues was important for teaching her the rules of the game, which allowed her to work within the system to accomplish her goals. As numeric representation becomes institutionalized via gender quotas and significant proportions of women serve in the legislature for multiple sessions, women will be better equipped to transfer institutional knowledge from one cohort of female legislators to the next.

Third, as numeric representation becomes institutionalized, women may begin to feel more confident about negotiating for and pursuing the legislative appointments that they want. Women in numerous interviews attest that being a numeric minority makes it more difficult to speak up and ask for what that want, but having other female colleagues can provide encouragement and confidence to overcome these barriers. A Mendoza deputy summarizes it nicely: “I think that the quota law has permitted women to participate more, to get more support, and to look at the one next to you who feels insecure and make them feel encouraged. We don’t feel alone.”[10]

As a result of these factors, though women may initially be sidelined, as they gain more experience in the legislature they may overcome institutional barriers and develop institutional knowledge that will better equip them to work within the system to gain access to desirable committee appointments.In other words, although gender quotas accompanied by a sharp increase in numeric representationmay initially increase the marginalization of women, with time they will empower women. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to distinguish among the different factors that influence women’s committee appointments, all of the factors discussed above suggest that we should observe the same relationship between the duration of time since gender quota adoption and women’scommittee appointments. Accordingly, I test the following two hypotheses.

Marginalization Hypothesis: Conditional on women being newcomers to the legislative chamber, as the percentage of women in the legislative chamber increases, women will be more likely to be appointed to women- and family-oriented issuescommittees and social issues committees and less likely to be appointed to power and/or economic and trade committees.

Political Empowerment Hypothesis: Conditional on women holding a significant proportion of seats in the legislature, as the duration of time increases since the adoption of gender quotas, women will be less likely to be appointed to women- and family-oriented issues committees and social issues committees and more likely to be appointed to power and/or economic and trade committees.

4. The Argentine case

Gender quotas are still a relatively new political institution, so there are limited opportunities to examine a large number of legislatures over a significant duration to assess if and how women’s experience in the legislature changes overtime after the initial adoption of quotas. To address this challenge, I turn to the Argentinaat the subnational level where gender quotas have been in place since the early 1990s.Argentina is a federalist country with twenty-three provinces and an independent Federal District (henceforth referred to as a province). Eight of the provinces have bicameral legislatures while 16 are unicameral, for a total of 32 chambers. Focusing on the Argentine provinces allows me to look across a large number of chambers for a long period of time.

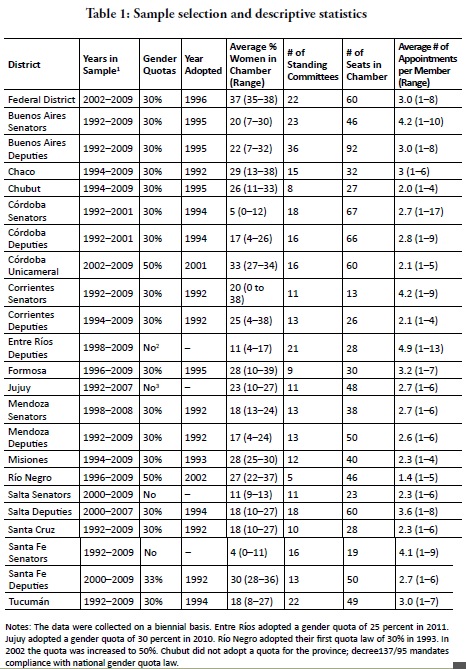

In 1991, the Argentine National Congress adopted the worlds first national gender quota law (Jones 1996; Edit and Giacobone 2001; Lubertino 1992). Following this, many of the provincial legislators began adopting quotas of their own (Archenti and Tula 2008; Barnes 2013; Jones 1998; Marx, Borner and Caminotti 2007). Between 1992 and 2000 all but a twoprovinces (Entre Ríos and Jujuy) in Argentine adopted a quota. (Table 1 lists the legislative chambers and years included in my analysis.)My analysis uses data from twenty-two Argentine provincial chambers. For most chambers,observations range from 1992, the year before gender quota adoption began to diffuse across the Argentine provinces, to 2009.The long temporal domain (up to eighteen years) allows me to examine how time since quota adoption influences women’s appointments to legislative committees across a large number of chambers.

I included committee data for each province where I was able to reliably obtain committee appointments for multiple years. Most of the information about committee appointments in the provinces for previous years is not available online or in the nation’s capital. For this reason, I traveled to 19 provinces in Argentina to collect data.It was not feasible for me to travel to all provincial legislature, thus with the exception of two bicameral legislatures (i.e., Entre Ríos and Corrientes) and two province in Patagonia (Chubut and Santa Cruz), I did notinclude any provinces in my sample that do not have at least thirty legislators in the lower chamber.[11]As detailed in Table 1, I was not able to obtain information for each chamber for the entire period understudy.The first year of the analysis is 1992 because prior to the 1992 elections, gender quotas were not used in any of the provinces. This enables me to incorporate information into my analysis about women’s committee appointments prior to quota adoption and their appointments after quota adoption. Two of the provinces in my sample, Entre Ríos and Jujuy did not adopt gender quotas until after 2009 (the last year in my sample). This wide variety in the adoption of quotas (i.e., some provinces adopted quotas in the early 1990, some adopted quotas much later, and some did not use quotas during my sample) is useful for statically distinguishing between the impact ofquota adoptions and women’s numeric representation. The long temporal domain is necessary to assess the duration of time necessary for gender quotas to influence women’s legislative committee appointments.

In my sample, women rarely occupy a notable proportion of legislative seats prior to the adoption of a gender quota; instead most of the provinces in Argentina had a very small proportion of women in office (lows range from 0 to 10 percentof total representation). Each chamber that adopted a gender quota, however, saw a significant increase in numeric representation over the period of time under analysis (resulting in close to 40 percentof total representation in some cases).

4.1.The committee system in the Argentine provinces

In the Argentine provinces, committee appointments are typically distributed to political parties in proportion to their seat share in the legislature. For the chambers in my sample, with the exceptions of Entre Ríos and Salta, this arrangement is explicitly stipulated in the chamber rules.[12] In Entre Ríos and Salta, the language is absent from the official rules, but numerous interviews indicate that the chamber norm is to distribute committee appointments proportionally amongst political parties.

At the beginning of the legislative session, each political party holds a meeting in which members from that party decide who will occupy each committee appointment allocated to the party. In the party meeting, each member has the opportunity to state his or her committee preferences, and then members of the party discuss among themselves and decide who will be appointed to each committee. Even though everyone has the opportunity to state his or her preferences, depending on the political party’s norms and other circumstances, the final decision may not always be democratic.Numerous interviews with provincial legislators from all of the chambers in my sample indicate that in some cases appointments are decided by an informal vote among party members but in other casesa few influential members of the party or the party boss himself decide them. Regardless of the party norms, typically the final decisions aresubject to the approval of the party boss. With only a few, extremely rare, exceptions party bosses are always men. This committee assignment process creates an environment in which the obstacles discussed above are major challenges that women must overcome to receive powerful committee appointments.

5.Committee data from the Argentine provinces

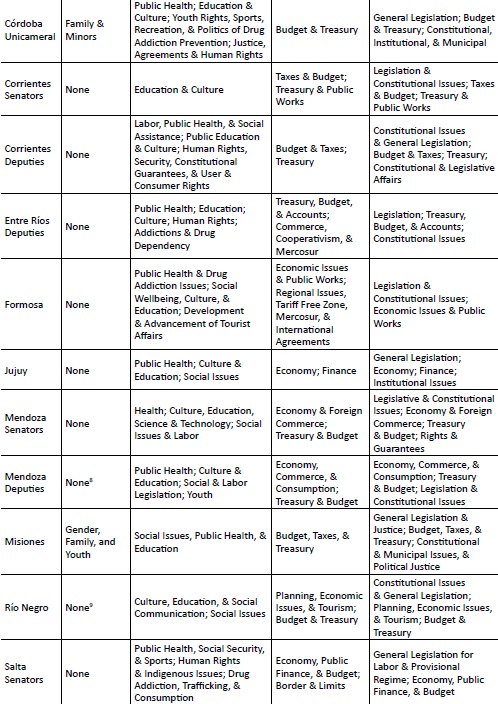

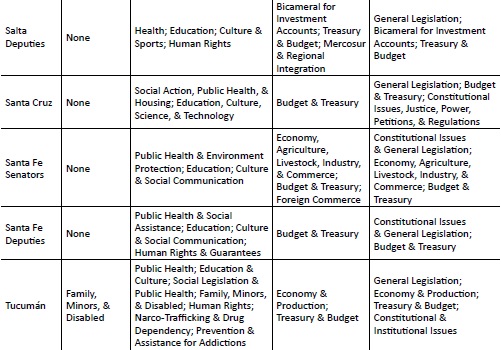

I analyze the probability that women will be appointed to four different (but not mutually exclusive) categories of legislative committees: Women and Family Committees (WFC), Social Issues Committees (SIC), Economic and Trade Committees (ETC), and Power Committees (PC). PCs are defined as the committees that have the most influence and power in the chamber. Interviews with numerous legislators in each of the chambers in my sample revealed that in the case of the Argentine provinces,PCs are typically the budget committee, the general legislation committee,and the constitutional issues committee.The Appendix provides a detailed coding of each committee category.

The unit of analysis is an individual legislator. Following Heath, Schwindt-Bayer, and Taylor-Robinson(2005),for each category each legislator is coded 1 if s/he sits on a committee that is classified as belonging to a given categoryand 0 otherwise.All legislators in my sample are permitted to sit on multiple committees in a given legislative session. This coding results in four dichotomous dependent variables.

5.1. Independent variables

I include both male and female legislators in my analysis, which enables me to compare women’s probability of appointment to men’s. As such, the first variable of interest in my analysis is the sex of the legislator. The variable labeled Female is coded 1 for female legislators and 0 for male legislators. The second variable of interest is Numeric Representation.I use the proportion of women in the legislature in a given legislative session to evaluate how the level of women’snumeric representation influence the probability that women will receive powerful committee appointments or be sidelined. Thethird variable of interest,Quota Years,measures the number of legislative sessionsin which a given chamber has used a gender quota.[13]In my analysis the number of sessions using a gender quota ranges from 0 to8.[14]

According to my hypotheses, each of the aforementioned relationshipsshould be conditional. The Marginalization Hypothesis is conditional on women being newcomers to the legislature (i.e., the time since quota implementation). The Political Empowerment Hypothesis is conditional on the proportion of women in the legislature. To address the conditional nature of these hypotheses I include a series of interaction terms. First, I interact Female with Numeric Representation toaccount for the expectations that numeric representation should influence women’s political appointments differently than men’s. Second, I interact Female with Quota Years to account for the expectation that the number of years since women have occupied a sizable proportion of the chamber’s seats should influence women’s appointments differently than men’s. Then, to account for the conditional nature of my hypotheses, I interact Numeric Representation with Quota Years as well as Numeric Representation, Quota Years, and Female.

In addition to my independent variables of interest, I control for a number of other factors that may influence committee appointments. First, individuals with more legislative experience may be more likely to be appointed to prestigious committees. To account for this effect,I control for previous legislative experience; Number of Terms in Officeis coded as a count of the number of terms that each representative has served. It is not the norm for legislators to serve multiple terms in office in the Argentine provinces.The average number of terms served by a legislator in my sample is 1.28. As such, the correlation between Number of Terms in Office and Quota Years is only .027 for women and .033 for men. The low levels of seniority found in the Argentine subnational context are consistent with the overall trends at the national level (Jones et al 2002).Individuals who are appointed to more posts may be more likely to hold prestigious committee appointments.Also, the number of appointments legislators hold will vary within legislative chambers but also across legislative chambers. Table 1 illustrates the variation in the number of appointments per legislator both across chambers and within chambers. On average men hold 2.61 appointments per session and women hold 2.78. This difference is statistically significant at the 99% confidence level using a two-tailed t-test.The variable Appointments measures the number of appointments each individual holds.It is worth noting that while it is common for legislators to hold multiple appointments, it is far less common that they hold appointments onmultiple PCs. In my sample, almost 63% of legislators do not serve on a PC, 31% of legislators hold one post on a PC, 6% of legislatorshold a post on two PCs, and less than 1% hold a post on three or more PCs. Next, women may be less likely to be sidelined in provinces with higher levels of gender equality. I control for gender equality using the Gender-Related Development Index (GDI), which accounts for gender disparities in life expectancy rates, adult literacy rates, and standards of living. Higher GDI indicates lower levels of gender disparity. I include a control that measures the number committee postseach legislator’s party holds within each category in a legislative session. This is labeled Number of Party Positions.In legislative sessions where there are more positions available in a given category, legislators may be more likely to receive an appointment in that area. Finally, I control for the Number of Committees in a given chamber. When legislators are spread across more committees they may be less likely to serve on any specific committee.

6. Analysis and results

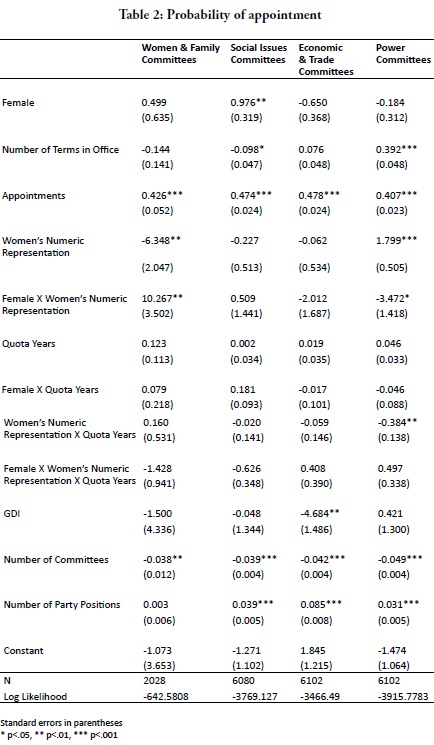

Given the dichotomous coding of my dependent variable, I use a logistic regression to estimate the likelihood of legislators being appointed to each type of committee. As previously stated, I examine the likelihood of appointment to four committee types, which results in four models, one for each dependent variable. The results are reported in Table 2.

Before discussing the results for my variables of interests, I will first briefly consider the relationship between several of my control variables and the probability of appointment to the four different types of committees. First, the models indicate that increases in the number of terms in office are not related to the probability of appointment to WFCs or ETCs. This may seem surprising that seniority is not related to appointments to ETCs, but a relatively small number of legislators actually serve multiple terms in office. For this reason, one’s social networks and previous experience may have more influence over committee appointments than the number of terms they have served in the provincial level legislature. Moreover, in the case of Argentian, Francheschet and Piscopo (2014) find that women do not typically have access to the same powerful political networks as men. These differences may help to explain the gender gap in ETC posts. Nonetheless, seniority is positively associated with appointments to PCs more generally and negatively associated with appointments to SICs. This indicates that although seniority is not a factor in determining appointment to the ETCs it is important for appointments to PCs more generally.

Most other control variables behave as anticipated. That is, legislators who hold more committee posts (Appointments) are more likely to be appointed to each committee type. In chambers with more committees (Number of Committees) the probability of being appointed to any of the four committee types decreases, indicating that legislators are spread thin across a larger number of committees. Finally, legislators who’s political party holds more positions (Number of Party Positions) on a given committee are more likely to receive an appointment to three of the four committee types, with WFCs as the outlier. The remainder of this section will focus on the main variables of interests.

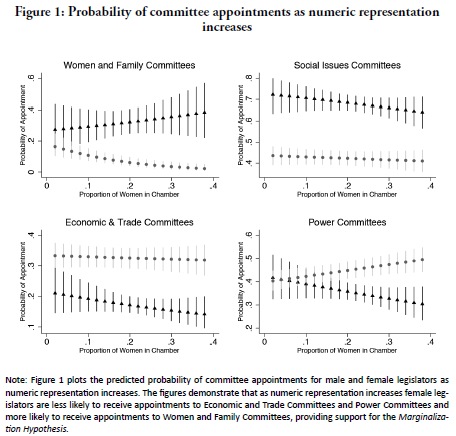

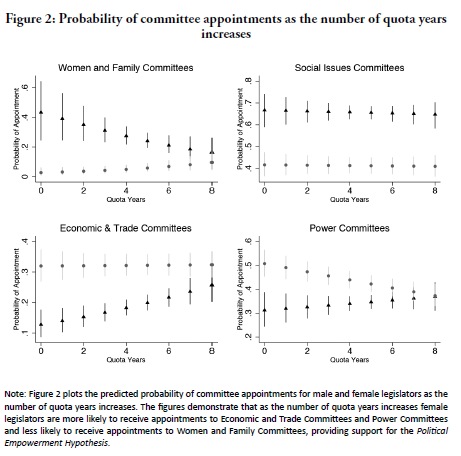

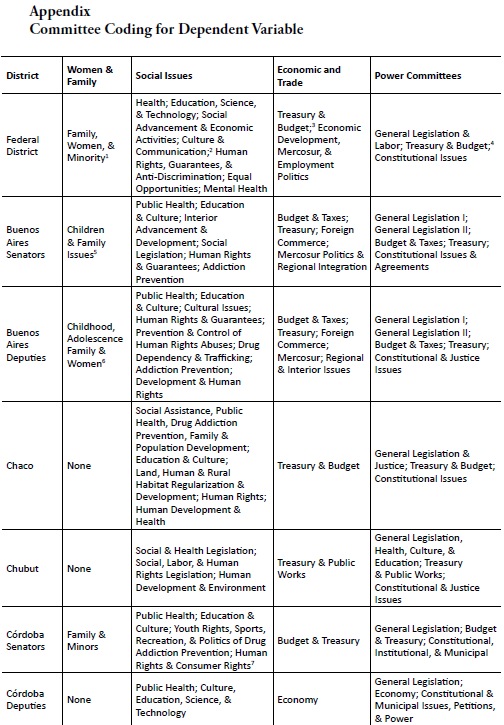

To facilitate the interpretation of the hypotheses, I use simulated coefficients to calculate sets ofpredicted probabilities of the average female and male legislator being appointed to each committee type over a large range of numeric representation and the range of quota years (King, Tomz, and Wittenberg 2000). I graph the predicted probabilities surrounded by 95 percent confidence intervals in Figures 1 and 2. The figures allow us to visualize how the probability of appointment to a given committee type changes for male and female legislators for various scenarios. At first glance, it is clear from both Figures 1 and 2 that on average female legislators are more likely than male legislators to be appointed to WFCs and SICs but less likely to be appointed to ETCs or PCs. It is also clear, however, that the probability of appointment to each of these committees changes as both numeric representation and the number of quota years increase.

6.1. Evaluating support for the marginalization hypothesis

First, consider support for the Marginalization Hypothesis,whichposits that when women, as a group, are newcomers to the legislature, increases in numeric representation may result in a higher probability of women being appointed to Women and Family Committee (WFCs) and Social Issues Committees (SICs) and a lower probability of being appointed to Power Committees (PCs) and/or Economic and Trade Committees (ETCs). To evaluate support for this hypothesis I calculate sets of predicted probabilities of male and female legislators being appointed to each of the four committee types as the proportion of women in the legislative chamber increases (see Figure 1). Given that the hypothesis is conditional on women being newcomers to the legislative chamber (and that I expect women to gain more access to powerful committee appointments when they are no longer newcomers), I hold the number of quota years at two (an equivalent of two legislative elections with gender quotas in provinces that hold elections every two years and one legislative election in provinces that hold elections once every four years).

Look first at the graph for WFCs on the top left of Figure 1. It is evident from this figure that women are more likely than men to be appointed to WFCs, and this relationship changes as the proportion of women in the legislative chamber increases. When women occupy only a small proportion of the legislative chamber, men and women are almost equally likely to be appointed to WFCs (the predicted probability of women occupying these posts is a bit higher than for men, but there is considerable overlap in the confidence intervals). As the proportion of women in the chamber increases,the difference in the probability of a woman being appointed to these posts as compared to a man increases, with women being more likely to be appointed to WFCs than men. This increase in the gap provides preliminary support for the Marginalization Hypothesis.

Similarly to the trend discussed above, women are more likely than men to be appointed to SICs. The graph on the top right of Figure 1 indicates that women, regardless of their numeric representation, are always more likely than men to be appointed to SICs.This relationship does not change for women or men as the proportion of women in the chamber increases.

Contrast this trend with the probability of being appointed to an ETC or to a PC. The bottom panel in Figure 1 plots the predicted probability of being appointed to ETCs on the left and the predicted probability of being appointed to PCs on the right. Men are more likely than women to be appointed to both ETCs and this trend does not change much as the proportion of women in the chamber increases. With respect to PCs, however, when women comprise a very small proportion of the legislative chamber, men and women are equally likely to be appointed to these posts, and a significant gender difference emerges as the proportion of women in the chamber increases. For example, when women comprise only 4 percent of the legislative chamber, men and women both have a .41 probability of being appointed to a PC. As the proportion of women in the legislative chamber increases, gender differences likewise increase. Once women comprise 30 percent of the chamber, their probability of being appointed to a PC drops to .32; but for men, their probability of being appointed to a PC increases to .47.As a result, men have a .15 higher probability than women of being appointed to a PC. This relationship is the exact opposite of the relationship observed between increases in numeric representation and the probability of being appointed to a WFC.

Taken together, the relationships observed in Figure 1 provide support for the Marginalization Hypothesis.Figure 1 illustrates that when women are newcomers to the legislature, sharp increases in numeric representation result in a higher probability of women being appointed to WFCs and a lower probability of women being appointed to an ETC or to a PC.

6.2. Evaluating support for the political empowerment hypothesis

While increases in numeric representation may initially lead to the marginalization of female legislators, I argue that over timefemale legislators will gain more experience in the legislature, enabling them to overcome institutional barriers and develop institutional knowledge that will better equip them to work within the system to gain access to desirable committee appointments. More specifically, the Political Empowerment Hypothesis posits that conditional on women occupying a sizable proportion of seats in the chamber, as the duration of time increases since the adoption of gender quotas, women will be less likely to be appointed to WFCs and SICs and more likely to be appointed to PCs and/or ETCs. To assess support for this hypothesis, I calculate sets of predicted probabilities of male and female legislators being appointed to the four committee types as the number of years since the implementation of gender quotas increases (see Figure 2). Given that the hypothesis is conditional on women holding a significant portion of the legislative seats in the chamber, I hold the proportion of female legislators at .30 and all other variables at their means.

Look first at the top left corner of Figure 2. Here I present the predicted probabilities of male and female legislators being appointed to WFCs. It is evident from the figure that female legislators are more likely than male legislators to be appointed to this type of committee. After only one session after quota implementation (when the proportion of women in the chamber is held constant at .30), women have approximately a .40 probability of being appointed to a WFC whereas their male counterparts have less than a .03 probability. The figure demonstrates that this trend changes over time: as time passes since the implementation of quotas, the probability of women being appointed to WFCs declines and the probability of men being appointed to these committees increases. Once quotas have been in place for seven sessions (or 14 years), the data predict no difference between the probability of male and female legislators being appointed to WFCs. This trend suggests that, over time, women are less likely to be pigeonholed into traditionally feminine committees.

Turning next to women’s appointments to SICs (in the top right corner of Figure 2), we see that women’s appointments to these committees are not influenced by the number of quota years. Similar to the results presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 demonstrates that female legislators are more likely than male legislators to be appointed to SICs and that this likelihood does not change as the number of quota years increases. In fact, the trajectory of the predicted probabilitiesis flat for both male and female legislators as the number of quota years increases.

Third, look at the bottom panel of Figure 2 to examine women’s appointments to ETCs and PCs. As before, the trends for both of these committees are similar to one another but are in sharp contrast to the trend reported in the top panel of Figure 2. The bottom panel of Figure 2 reveals that, initially, male legislators are far more likely to be appointed to both ETCs and PCs than are their female colleagues. As the number of years since quota adoption increases, this relationship dissipates. With respect to PCs, increases in quota years result in a significant decline in the probability that male legislators will be appointed to PCs and a significant increase in the probability that female legislators will be so appointed. Strikingly, as the number of quota years increases, the probability of appointment for male and female legislators begins to converge until there is nostatistical difference in the probability of male and female legislators being appointed to these PCs. After six legislative sessions (or 12 years) women and men are equally likely to be appointed to PCs.The data predict that the adoption of gender quotas does not result in immediate positive outcomes for women but that, over time, women can achieve access to powerful committee appointments. With respect to ETCs, men’s probability of appointment to these committees does not change over time, but women’s does. As the number of quota years increase women’s likelihood of appointment to an ETC increases. The model predicts that when women hold thirty percent of seats in the chamber they will be just as likely as men to be appointed to an ETC after eight legislative sessions (or 16 years) using gender quotas.

Taken together, the change in predicted probabilities of appointment to WFCs, ETCs, and PCs as the number of quota years increases provides strong support for the Empowerment Hypothesis and tells an encouraging story about women’s influence in the legislature. Together, these three sets of findings demonstrate that, over time, female legislators gain access to valuable resources such as powerful committee appointments within the legislature.It is also important to point out that these findings cannot be explained by women’s seniority in office. Recall that the statistical model controls for the number of terms a legislator has served in office and in my sample legislators serve on average only 1.28 terms. As such the results reported here indicate that the number of quota years has an effect independent of seniority.

7. Discussion

This paper offers exciting results, which indicatethat while women, as newcomers to a male-dominated legislative arena, may initially be marginalized and passed over for powerful committee appointments, as numeric representation becomes institutionalized in the legislative system women may learn to navigate the legislature and gain access to powerful posts. This result suggests that,while the adoption of gender quotas may result in initial backlash and sidelining of female legislators, with time (albeit a substantial amount of time, that is, six to eight sessions or 12 to 16 years) the implementation of gender quotas can result in the institutional integration of female representatives.

The only set of results that do not provide support for this argument is women’s appointments toSICs. Despite increased access to PCs and ETCs, women tend to be overrepresented in SICs, and this does not change significantly as numeric representation increases or as the number of quota years increases. Women’s overrepresentation on SICs may be a product of a combination of factors.

First, women’s overrepresentation on SICs may be a product of gender bias and stereotypes that view women as being better suited to serve in a traditionally feminine capacity.As a result of these stereotypes, men may be more likely appoint women to SICs as a way of pigeonholing them.A deputy from the Federal District explains that “just like at work, there are also [stereotypes] when it comes to committee politics. Committees related to services, education, women, health, social advancement, all have women as a majority. Because that is where men think women should be and women too.”[15]Comments from a Salta deputy reinforce this perspective: “Here, you do not get the job by ability. Here the personnel and women are designated in a different way. That makes the discrimination easy to see. You don’t really see a number of women in relevant positions.”[16]

Second, women could be consistently self-selecting into these committees, possibly because they genuinely prefer to serve on SICs (Carroll 2008). In her survey analysis of national legislators in Latin America,Schwindt-Bayer (2010) finds that women are more likely than men to prioritize social issues and as a result prefer to be placed on SICs.Moreover, at the subnational level, it may be the case that these committees are fairly attractive committees to serve on. The Argentina, subnational governments have jurisdiction over a large number of healthcare and education policies (Franceschet 2011). As such, legislators serving on these committees may have more influence over the formation of important social and welfare policies. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge many of these policies require government funding, andthe social issues committees do not have authority to appropriate funds.

Third, overrepresentation in these areas may be a product of women’s background and training prior to entering the legislature. A senator from Mendoza suggests that variations in committee appointments are a product of professional experience and expertise: “We have more female professors who are in the Education Committee, and, for example, in the General Legislation and Institutional Issues the majority are lawyers.… committee appointments have to do more with expertise than with gender.”[17]

If women’s overrepresentation in SICs is a product of women self-selecting because of their preferences and preparedness to serve on these committees, gender bias in committee appointments is a product of a larger gender bias in society.Stereotypes about men’s and women’s roles in the public and private sector track women intoa subset of careers(social issues and traditional feminine areas) from anearly stage. The employment and reinforcement of gender roles in society result in men and women developing different skills, priorities, and/or preferences. To the extent that women’s committee appointments are a product of more entrenched patterns in society, we should not expect women’s committee appointments to change over timeas a product of increases in the number of quota years.This change would require more fundamental changes in society, not only in the legislative arena.A Mendoza deputy articulates this point: “What happens is that stereotypes are established in a way that people see as natural, they don’t see it, it’s not visible. That is why it is necessary to raise awareness and consciousness, to remove the innocence and make sure that it [the way that stereotypes are established] is seen.… We are in a historical moment where we are gaining gender consciousness, but we have to intensify it, talk about it, demonstrate it, and teach it in schools. We have to make children picture both sexes with the same rights –different in sex, but equal in rights. The little boy can wash the dishes, and the little girl can play with cars.”[18]

8. Conclusion

While scholars and practitioners have long debated the benefits and pitfalls of gender quotas (Mansbridge 2005; Kittilson 2005; Jones 2005), it is undeniable that the implementation of gender quotas worldwide has been instrumental in providing women access to the legislative arena. Sill, many have raised concerns about women’s lack of institutional incorporation and their (in)ability to influence the legislative process once gender quotas enable their election to political office. Multiple studies provide evidence for these concerns, demonstrating that women do not receive the same legislative appointments as their male colleaguesand that they are more likely to be excluded as the proportion of women in the chamber increases.Are female legislators destined to remain on the sidelines, or is it possible for them to make lasting gains over time? In this research I argue that,although women’s debut to the legislative arena may be colored by marginalization, with time and persistence women’s role in the legislature is likely to change.

In particular, I suggest that as newcomers, women may face discrimination, lack necessary technical and legislative skills, and avoid asking and negotiating for what they want. For these reasons, the adoption of gender quotas accompanied by sharp increases in numeric representation may result in systematic differences between female and male legislators’ committee appointments. Consistent with this argument, this research demonstrates that when women are newcomers, as numeric representation increases they are less likely to receive valuable committee appointments and are more likely to receive appointments to committees that address stereotypical feminine issues.

Nevertheless, the outlook for women’s access to legislative power may not be completely grim. Rather, this research suggests that, in time,women’s access may improve. Discrimination in the chamber may dissipate, women will develop the technical and legislative skills necessary to adeptly maneuver in the legislative system, and women may become more inclined to ask for the committee appointments they want. Together, these changes will facilitate women’s access to powerful appointments. In particular, this research provides evidence that, over time, women may become much more likely to receive powerful committee appointments on both economic and trade committees and power committees, giving them influence over important policy decisions and preparing them for other important policy appointments in the government.

The downside is that this research indicates the amount of time necessary for women to approach equal footing with male legislators is not insignificant. The results presented here estimate that it took women betweensix and eight legislative sessions(12 to 16 years) after the implementation of quotas before they started receiving similar committee appointments to those of their male counterparts. Nonetheless, these findings illustrate the instrumental role of gender quota laws and their ongoing importance in facilitating opportunities for women. When reflecting on the consequences of the quota law,a Federal Districtdeputy argues,“The quota law has been really important. We still need to defend it because some people want to remove it, and that would be taking a step back. The cultural change still is not over; but yes, we have advanced. There is larger women’s representation in places where women were not before.”[19]

Nonetheless, even when women receive similar committee appointments to men, they stillhave a long way to go to achieve equal representation. Countless interviews indicate that women lack equal access to legislative leadership positions and that men continue to be unfairly privileged in this regard.A female deputy from the Federal District articulates this pervasive concern: “There is still a lack of equality. If we are going to elect someone, it has to be because of qualifications. We are still lacking that step. We have to keep working and empowering women for that.”[20] If the results from this research can be generalized to make predictions about women’s ability to obtain leadership positions, they suggest that, with time, women will gain access to the upper echelons of legislative leadership. For now, it is premature to conclude that women’s ability to gain access to powerful committee appointments also translates to their ability to obtain access to leadership posts.

Bibliography

Archenti, Nélida and María Inés Tula (2008). “La ley de cuotas en Argentina. Un balance sobre logros y obstáculos”. In Mujeres y Política en América Latina. Sistemas Electorales y Cuotas de Género.Buenos Aires: Heliasta.

Babcock, Linda and Sarah Laschever(2007). Women Don’t Ask. New York, NY: Batman Books.

Bækgaard, Martin and Ulrik Kjaer(2012). “The gendered division of labor in assignments to political committees: Discrimination or self-selection in Danish local politics?” Politics& Gender 8(4): 465-482.

Barnes, Tiffany D. (2013). “Gender and Legislative Preferences: Evidence from the Argentine Provinces”.Politics & Gender8(4): 483-507.

Bauer, Gretchen and Hannah E. Britton (eds.)(2006). Women in African Parliaments. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Beckwith, Karen(2007). “Numbers and newness: The descriptive and substantive representation of women.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 40(1): 27-49.

Brown, Alice, Tahnya Barnett Donaghy, Fiona Mackay and Elizabeth Meehan(2002). “Women and Constitutional Change in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland”.Parliamentary Affairs 55(1): 71-84.

Carroll, Susan(2008). “Committee assignments: Discrimination or choice?” In Beth Reingold (ed.)Legislative Women: Getting Elected, Getting Ahead. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, pp. 135-156.

Eagly, Alice H. (1987). Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eagly, Alice H.(1995). “The science and politics of comparing women and men”.American Psychologist 50(3): 145-158.

Eagly, Alice H., Mary C. Johannesen-Schmidt and Marloes L. van Engen (2003). “Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men.”Psychological Bulletin 129(4): 569-591.

Fenno, Richard (1997). Learning to Govern. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Franceschet, Susan(2011). “Gender policy and state architecture in Latin America”.Politics & Gender 7(2): 273-279.

Franceschet, Susan and Mona Lena Krook (2008). “Measuring the impact of quotas on women’s substantive representation: Towards a conceptual framework.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, MA, August 28-31.

Franceschet, Susan, and Jennifer Piscopo(2008). “Gender quotas and women’s substantive representation: Lessons from Argentina”.Politics & Gender4(3): 393-425.

Franceschet, Susan, and Jennifer Piscopo(2014). “Sustaining gendered practices? Power and elite networks in Argentina”. Comparative Political Studies 47(1): 86-111.

Funk, Kendell, Laura Morales and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson (2014). “De-gendering an institution? Findings from Costa Rica’s Legislative Assembly”. Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, April 3-6, 2014.

Frisch, Scott A., and Sean Q. Kelly(2003). “A place at the table: Women’s committee requests and women’s committee assignments in the U.S. House”.Women & Politics 25(3): 1-26.

Gallo, Edit and Carlos Alberto Giacobone (2001). Cupo Femenino en la Política Argentina: ley Nacional; Leyes Provinciales; Debates Parlamentarios; Normative Internacional; Jurisprudencia. Buenos Aires: Eudeba.

Grey, Sandra(2006). “Numbers and beyond: The relevance of critical mass in gender research.” Politics & Gender 2: 491-530.

Heath, Roseanna Michelle, Leslie A. Schwindt-Bayer, and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson (2005). “Women on the sidelines: Women’s representation on committees in Latin American legislatures”.American Journal of Political Science 49(2): 420-436.

Heilman, Madeline E. (1995). “Sex stereotypes and their effects in the workplace: What we know and what we don’t know”.Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 10(6): 3-26.

IPU (Inter-Parliamentary Union)(2012). Women in National Parliaments. Available from: http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm (September 1, 2013).

Jones, Mark P. (1996). “Increasing women's representation via gender quotas: The Argentine Ley de Cupos”.Women & Politics 16(4): 75-98.

Jones, Mark P. (1998). “Gender quotas, electoral laws, and the election of women: Lessons from the Argentine provinces”.Comparative Political Studies 31(1): 3-21.

Jones, Mark P. (2005). “The desirability of gender quotas: Considering context and design.”Politics & Gender1(4): 645-652.

Jones, Mark P. (2009). “Gender quotas, electoral laws, and the election of women: Evidence from the Latin American vanguard”.Comparative Political Studies 42(1): 56-81.

Jones, Mark P., Sebastian Saiegh, Pablo Spiller and Mariano Tommasi(2002). “Amateur legislators–professional politicians: The consequences of party-centered electoral rules in a federal system”.American Journal of Political Science 46(3): 656-699.

Kerevel, Yann, and Lonna Rae Atkeson(2013). “Explaining the marginalization of women in legislative institutions”.Journal of Politics 75(4): 980-992.

King, Gary, Michael Tomz and Jason Wittenberg (2000). “Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation”.American Journal of Political Science 44(2): 347-361.

Kittilson, Miki Caul(2005). “In support of gender quotas: Setting new standards, bringing visible gains”.Politics & Gender1(4): 638-645.

Lubertino, M. J. (ed.)(1992). Cuota mínimo de participación de mujeres: El debate en Argentina. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Fundación Friedrich Ebert.

Mansbridge, Jane(2005). “Quota problems: Combating the dangers of essentialism.” Gender & Politics 1(4): 622-638.

Marx, Jutta, Jutta Borner, and Mariana Caminotti (2007). Las Legisladoras: Cupos de Género y Política en Argentina y Brasil. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

O’Brien, Diana Z(2012). “Gender and select committee elections in the British House of Commons”.Politics & Gender8(2) 178-204.

Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. (2009). “Making quotas work: The effect of gender quota laws on the election of women.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 34(1): 5-28.

Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. (2010). Political Power and Women’s Representation in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thames, Frank C. and Margaret S. Williams (2013). Contagious Representation: Women’s Political Representation in Democracies around the World. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Thomas, Sue(1994). How Women Legislate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Towns, Ann(2003). “Understanding the effects of larger ratios of women in national legislatures: Proportions and gender differentiation in Sweden and Norway”.Women & Politics 25(1): 1-29.

Tula, María Inés (2008). “La ley de cuotas en la Argentina”. In Nélida Archenti and María Inés Tula (eds.) Mujeres y Política en América Latina: Sistemas Electorales y Cuotas de Género. Buenos Aires: Heliasta, pp. 31-53.

Zetterberg, Pär (2008). “The down side of gender quotas? Institutional constraints on women in the Mexican State legislatures”.Parliamentary Affairs 61(3): 442-460.

* Artículo recibido el 03 de setiembre de 2013 y aceptado para su publicación el22 de agosto de 2014.

**PhD in Political Science; Assistant Professor, University of Kentucky; tiffanydbarnes@uky.edu

[1] Select committees are special oversight committees in the UK Parliament (see O’Brien 2012).

[2] But see Heath, Schwindt-Bayer and Taylor-Robinson (2005), Schwindt-Bayer (2010), and Kerevel and Atkeson (2013) for examples of studies that compare appointments from before and after quota adoption.

[3] Interview with Front for Victory (Frente para la Victoria, FpV) legislator, Salta, July 10, 2013.

[4] These same findings do not hold in the case of Costa Rica (Schwindt-Bayer 2010). If quotas do not result in a sizable increase in women’s representation, it is unlikely that they will result in significant backlash. For example, in the case of Mexico, quota adoption only resulted in a 7 percent increase in numeric representation, and Kerevel and Atkeson (2013) find little evidence of marginalization.

[5] Interview with FpV deputy, Entre Ríos, July 16, 2013. Translation here and throughout the paper is the author’s.

[6] Interview with FpV deputy, Entre Ríos, July 16, 2013.

[7] Interview with Federal District deputy from a small third party, July 16, 2013.

[8] Interview with Radical Civic Union (Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) deputy, Mendoza, June 26, 2013.

[9] Interview with UCR senator, Mendoza, June 27, 2013.

[10] Interview with UCR deputy, Mendoza, June 26, 2013.

[11] I did not travel to Santa Cruz. I was able to obtain committee appointments for Santa Cruz via email correspondence with the provincial legislature. I included the two additional provinces in Patagonia because small legislatures (those with fewer than 30 members in the lower chamber) are over represented in Patagonia. I did not want to bias my sample by under sampling this region since the other regions are well represented in the sample.

[12] Seats are not distributed proportionally in the Córdoba Unicameral Chamber or former Córdoba Lower House. The chamber rules reserve five seats for the majority party, two for the largest minority, and one for the remaining minority parties.

[13] If a chamber never adopted a gender quota, it is coded 0 for every observation period. The results in the analysis are robust to the exclusion of legislative chambers that did not adopt a gender quota during my period of analysis (i.e., Entre Ríos deputies, Salta senators, and Santa Fe senators).

[14] In cases where my data begin after quota adoption, the number of years since quota adoption is still coded as a count of the number of years since implementation; as a result, the first observation in the data for some chambers may be greater than one. The one exception to this is the Federal District where gender quotas were adopted in 1991 for municipal elections. The Federal district does not have its own gender quota; rather it implements the national gender quota law (Tula 2008). The same quota rule was applied when the Federal District became independent and held the first election as an autonomous district in 1996. While there were other municipal elections prior to this date, this is technically the first election as an autonomous district and is therefore used as the starting date for quota implementation.

[15] Interview with Federal District deputy from a small third party, July 16, 2013.

[16] Interview with Acción Cívica y Social legislator, Salta, July 10, 2013.

[17] Interview with FpV senator, Mendoza, June 25, 2013.

[18] Interview with Mendoza, FpV deputy, Mendoza, June 26, 2013.

[19] Interview with Federal District deputy from a small third party, July 16, 2013.

[20] Interview with Federal District deputy from a small third party, July 16, 2013

[24] Formerly Women, Childhood, Adolescence, & Youth Committee

[25] Formerly Culture Committee

[26] Formerly Budget, Hacienda, Financial Administration & Tributary Politics Committee

[27] Formerly Budget, Hacienda, Financial Administration & Tributary Politics Committee

[28] Formerly Childhood, Adolescence, & Family Committee

[29] Formerly Childhood, Adolescence, & Family Committee. In 1998 the Women’s Issues Committee was created. In 2002 these two committees were consolidated to make the Childhood, Adolescence, Family, & Women Committee.

[30] Formerly Justice, Human Rights & Agreements Committee

[31] The Mendoza Chamber of Deputies created a special committee focused on gender in 2009. Every female in the Chamber of Deputies was a member of the committee in 2009.

[32] In 2000 Río Negro created the Special Committee on the Study of Gender. It is not a standing committee and does not meet on a regular basis.