Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política

versión On-line ISSN 1688-499X

Rev. Urug. Cienc. Polít. vol.23 no.spe Montevideo dic. 2014

GENDER BALANCE IN COMMITTEES AND HOW IT IMPACTS PARTICIPATION: EVIDENCE FROM COSTA RICA’S LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY*

Equilibrio de género en las comisiones y cómo impacta sobre la participación: Evidencia de la Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica

Kendall Funk* and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson**

Abstract: We examine participation by women and men in legislatures in a critical case. Previous studies found that women often participate less than men in committee hearings and plenary debates. Yet these studies were conducted in cases where women held a fairly small share of seats and generally did not hold leadership positions or have seniority – factors expected to decrease participation. We use data from the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly (2010-2012) to assess whether women still participate less than men when placed in conditions of (near) institutional equality. Costa Rica has a successful 40% gender quota, a woman president, and no immediate reelection to the Assembly so all deputies lack seniority, thus many sex barriers have been broken in Costa Rican politics. In this apparently favorable environment, do women deputies participate equally with men? We answer this question using data from two standing committees, which offer variance on the percentage of women in attendance at each session. Empirical findings suggest that women participate as much as men in committee, even when the number of women on the committee is few. We also find that committee leaders are very active participants, which underscores the importance for women of obtaining committee leadership positions.

Key Words: Costa Rica; legislative branch; committee participation; women

Resumen: Examinamos la participación de mujeres y hombres en legislaturas en un caso crítico. Estudios anteriores han encontrado que las mujeres muchas veces participan menos que los hombres en las discusiones en comisión y en los debates en el plenario. No obstante, estos estudios se realizaron sobre casos en que las mujeres ocupaban una proporción relativamente pequeña de los escaños y generalmente no ocupaban puestos de decisión ni tenían antigüedad –factores que tienden a reducir la participación. Usamos datos de la Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica (2010-2012) para evaluar si las mujeres participan menos que los hombres aun cuando estén en condiciones de (casi) igualdad institucional. Costa Rica tiene una cuota exitosa de un 40%, una mujer presidenta, y no está permitida la reelección inmediata a la Asamblea, así que ningún diputado tiene antigüedad, por lo que muchas barreras de género se han superado en la política costarricense. En este entorno aparentemente favorable, ¿las diputadas participan a la par de los diputados? Respondemos a esta pregunta utilizando datos de dos comisiones permanentes que ofrecen una varianza en el porcentaje de mujeres que asisten a cada sesión. Los hallazgos empíricos sugieren que las mujeres participan tanto como los hombres en las comisiones, aun cuando hay muy pocas mujeres en la comisión. También encontramos que los y las presidentes/as de las comisiones tienen una participación muy activa, lo que subraya la importancia de que las mujeres obtengan puestos de liderazgo en las comisiones.

Palabras clave: Costa Rica; poder legislativo; participación en comisiones; mujeres

1. Introduction

For many years, academics, women’s groups, and international organizations have shown interest in studying the effects of increasing the representation of women in government. Much of the literature and the real world effort have focused on legislatures. Legislatures are intended to be representative bodies that reflect the interests of society in the policy-making process. If women are not included in legislatures, the “representativeness” of the legislature is called into question. Recently, some legislatures have adopted policies aimed at increasing the number of female representatives. Yet, is election of a larger number, but still a minority of women enough to provide representation, or do conditions in the legislature need to permit, and possibly even promote, actual participation by these women? Much of the work of legislatures takes place in committees, and women are often still found in small numbers on committees in the economics policy domain and power committees, which may still be a barrier to women participating in many places in the legislature. In addition, women often are under-represented in leadership posts, which may also be a barrier to participation.

This paper contributes to our understanding of the conditions under which women are likely to participate as much as their male colleagues. We examine participation by women and men in standing committees in the Costa Rican Assembly. Committees offer several advantages for studying participation in the legislative process. Different committees have jurisdiction over different policy areas, so we can explore whether and how participation varies with the sex of the legislator across policy topics. Committees are small groups relative to the size of the full chamber, which can facilitate participation by all members, particularly as members have time to build rapport. Committeeoperation is generally removed from intense public scrutiny, which may facilitate cross-party participation. Thus, party effects that might otherwise be misconstrued as gender effects are diminished and less likely to dampen participation. Committees also provide variation in their gender composition while holding all other aspects of the political system constant, thus offering a true most similar systems design.

Our central research question is whether the sex of the legislator predicts differences in participation in committees. This question grows out of Rosabeth Kanter’s (1977) research about how group interaction dynamics are influenced by the sex ratio in the group.[1]Kanter predicted that in “skewed groups,” when women are about 15% or less of the group’s members, male norms will pertain, and in general the few “token” women present will not want to stand out or draw attention to themselves, though some women may opt to act as representatives for their group. As women become more numerous (what Kanter labeled a “tilted group” with approximately a 65/35 ratio), women will be more willing to take action,[2] but there may also be backlash by men (Kathlene 1994; Bratton 2005). This project also grows out of findings that women, even once they obtain seats in the legislature, often either do not participate or they are not allowed to participate as much as their male colleagues (see e.g. Piscopo 2011; Walsh 2012).[3] This finding suggests that achieving gender equality is a complex process that merits further research.The literature has yet to uncover whether lack of gender equality is caused by gender dynamics, institutions that disadvantage women, women holding a relatively small percentage of seats in a chamber or committee, and/or women lacking seniority and leadership posts.

2. Prior studies of women’s participation in legislatures

Studies of participation in plenary session debates sometimes find that women participate less than their male colleagues, while other studies do not find a significant gender difference. Studies looking at terms before the “year of the woman” in the U.S. Congress, or before the spread of gender quotas in many countries, found that women spoke less than the men (see Diamond 1977; Kathlene 1994; Thomas 1994; Taylor-Robinson and Ross 2011). However, studies of more recent legislatures have found participation in plenary session debates to be equal for women and men (see Broughton and Palmieri 1999 on Australia; Murray 2010a on France; Pearson and Dancey 2011 on the U.S.). Research also finds that women participate more in debates about “women’s issues” bills even when there are few women elected to a chamber (see Bicquelet, et al. 2012; Catalano 2009; Chaney 2006; Childs and Withey 2004; Pearson and Dancey 2012; Piscopo 2011; Swers 2014; Taylor-Robinson and Heath 2003; see Swers 2001 for a review of U.S. literature). This suggest that, all else equal, women may be more inclined to participate in standing committees whose policy domains include women’s issues rather than committees whose policy purview is a traditionally masculine policy domain.

Research thus far has been unable to disentangle the possible causes of gender differences in participation. Findingsin prior studies about participation by women that appeared to be gendered may have been a function of women being insufficiently numerous in the legislature, lacking in the seniority required for serious participation, lacking in leadership posts that involve much participation, or all of the above. Legislatures, and their standing committees, can be gendered institutions. Most legislatures were established before women had the right to vote or hold office, so presumably the institution’s organization, formal rules of operation, and informal norms of behavior were developed to accommodate the career needs and participation styles of male politicians and party leaders. For example, “If women’s private-sphere backgrounds rendered them more nurturing, accommodating, and gentler than men, would they be able to participate fully in the masculine state legislature?” (Kenney 1996, quoted in Cammisa and Reingold 2004: 187-8). Studies have found male legislators to be rude or patronizing to their female colleagues, especially when women’s presence in legislatures was new (Darcey 1996, cited in Cammisa and Reingold 2004: 189; Walsh 2012) or when increasing numbers of women start to become threatening to men’s political career opportunities (Kathlene 1994).

“The term ‘gendered institution’means that gender is present in the processes, practices, distribution of power, andimages and ideologies in the various sectors of social life”(Acker 1992: 567). The gender and politics literature recognizes the rules of the game of legislative politics as “inherently gendered. Dominant norms and approaches to policy making and leadership are described in masculine terms: hierarchical, authoritative relationships; zero-sum competition and conflict; and interpersonal dynamics involving coercion and manipulation” (Reingold 2008: 132; also see Duerst-Lahti 2002; Beckwith 2005). Cammisa and Reingold (2004: 182) explain that much research on women in U.S. state legislatures has focused on “how well, and to what extent, women legislators are integrated and included in the process and how the influx of women in legislatures can change legislative agendas, processes, and outcomes.” These questions are also relevant to the cross-national study of women in politics.

One observable implication of the theory that legislatures are gendered institutions can be seen through the over-representation of women on committees with a traditionally feminine policy domain and the under-representation of women on “power” committees (see Aparicio and Langston 2009 [Mexico]; Barnes 2014 [Argentina]; Zetterberg 2008 [Mexico]; Heath et al. 2005 [6 Latin American countries]; Murray 2010b [France]; Towns 2003 [Norway and Sweden]; Frisch and Kelly 2003 [US]). Many female legislators may have a genuine policy interest in the topics covered by committees with a stereotypically feminine policy domain (e.g., women’s affairs, education, social welfare) and therefore asked to serve on these committees, so their committee assignments may not indicate they are being marginalized (see Zetterberg 2008: 452). Parties may also want their women legislators to serve on committees with feminine policy domains if policy issues within those committees’ domains are important to the party’s platform, as the party may view its female representatives as better spokespeople for the party’s policy on issues such as education or healthcare (see Swers 2002,2014). However, it is unlikely that politically ambitious women politicians are uninterested in posts on “power” committees.[4] Hence the frequent finding that women are under-represented on “power” committees may indicate a gendered nature to the institutions.[5]

3. Studying participation

Participation can be measured in various ways, and in different venues, within the legislature. Legislators initiate bills, vote, and speak in plenary session debates, committees, and sub-committees.We study participation in committee hearings in Costa Rica’s Assembly because the fate of many bills is decided within committees: many bills die in committee and special rules are rarely used to call these bills forward to the plenary(Alemán 2006). Committees canalso amend bills, and they hold hearings on bills that give the public (at least the sectors of the public that the committee members choose to consult) an opportunity to weigh in on whether a bill should be passed, modified, or killed. In sum, committees are gate-keepers within legislatures (Calvo forthcoming; Taylor-Robinson and Ross 2011) so we think that it is important to observe how female and malelegislators avail themselves of the opportunity to participate in committees.

Hall’s (1996) study of participation in committees in the U.S. House of Representatives provides a useful template for studying committee participation. Hall measured formal participation through attendance, voting, participation in markup debate, proposing motions or amendments, and engaging in agenda action.We borrow three of Hall’s forms of formal participation to analyze participation by women and men in Costa Rican standing committees: speech in committee sessions, proposals of motions to amend a bill, and proposals of motions to bring in consultation on a bill.

We expect that when placed in a condition of (near) institutional equality, and all else being equal, there is no difference in the behavior of male and female legislators. However, we expect that equality of the sexes within an institution is influenced by the sex ratio of chamber/committee members, leadership roles, seniority and experience, and party affiliation. Our primary focus, and our main explanatory variable regarding participation in committees is the sex ratio of members on the committee (the composition of the committee during any given session). Drawing on Kanter (1977), participation by women may increase as the percent of women in attendance at a session increases, at least when the increase moves the committee’s sex ratio from “skewed” to “tilted”. We hypothesize that:

H: As the percentage of women in attendance at a committee session increases, the participation of women on the committee also increases.

Other aspects of committee composition, including the traits of individual members, may also affect participation for both men and women, so we control for as many of these factors as possible in our analysis. The sex of the committee leader may affect participation, as research has found that the committee leadership styles of men and women differ, for example, in how inclusive they are (see Kathlene 1994; Rosenthal 1997, 2005). Committee presidents – regardless of their sex – may be especially active because their position allows them to participate when they wish, and they control the pace of debate. Deputies may be more likely to participate if they have experience on the committee (i.e. if they have been assigned to the committee previously).[6]Party may impact participation. Deputies from the governing party may be more likely to participate to help pass their party’s legislative agenda. Alternatively, opposition deputies may be active, while deputies from the governing party may let the executive branch propose and lobby for the government’s agenda.

4. Costa Rican standing committees:A nearly ideal place to study participation

As mentioned above, institutional equality can occur (or not occur) at the level of the chamber as a whole, and at the committee level. The structure of Costa Rica’s Assembly and its election law, along with the history in recent decades of incorporating women make the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly a case where there are many indicators of institutional equality for the chamber as a whole. Costa Rica is Latin America’s oldest and most stable democracy. In 2010 Costa Ricans elected their first woman president, Laura Chinchilla of the National Liberation Party (PLN).A woman was elected as one of the two vice-presidents of the country for the first time in 1986. Women have held diverse posts in the cabinetand for the period studied here women held 5 of 22 full cabinet-rank posts. Women gained the right to vote in 1949 and the first woman was elected to the Assembly in 1953.While women held less than 10% of the Assembly’s 57 seats until 1986 and between 12% and 14% of seats throughout the 1990s,in 1998 Costa Rica adopted a national gender quota of 40% and since its first implementation in the 2002 election women have held at least 35% of the seats.[7] In the 2010 – 2014 term women won 38.6% of seats. While women are not at parity with men, the percentage of women in party caucuses is greater than 40% for the three largest parties (Liberación Nacional [PLN], Acción Ciudadana [PAC], and Movimiento Libertario [PML]).[8]Immediate reelection is prohibited, and in practice few deputies return, which eliminates the challenge for women of male legislators typically having much higher rates of seniority (Schwindt-Bayer 2005).[9]

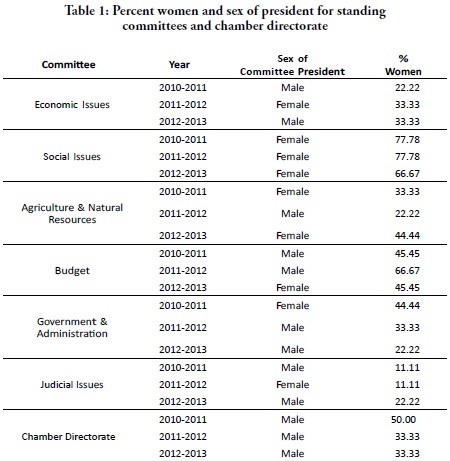

Women began to hold prestigious leadership posts in the Assembly in the 1980s when Rosemarie Karpinsky was selected as the Assembly President for 1986.Karpinsky also served as the president of the Economics Issues committee—the Assembly’s most prestigious committee. The Assemblyhas six permanent standing committees: Economics Issues, Social Issues, Agriculture & Natural Resources, Budget, Government & Administration, and Judicial Issues. Chamber leadership and committee assignments are made yearly for one-year terms. No woman held the Assembly President post during the 2010-14 term; however, women held 3 of the 6 standing committee president posts for each of the first three years of the term (the period we analyze).Table 1 lists the gender makeup of the Assembly Directorate and each of the standing committees for each year in our dataset.

All standing committees have 9 members, except the Budget Committee, which has 11 members, and deputies serve on one standing committee each year. The Assembly President makes committee assignments yearly, though some deputies are reassigned to the same committee.Committee composition varies from meeting to meeting based on attendance. For the two committees we study attendance averaged 83% (range 56-100%). With fluctuations in attendance the percentage of women present at Economics Committee sessions ranges from 13-60% (mean 31%), and at Social Committee sessions from 60-100% (mean 81%). Since 2003, committee seats have been allocated proportional to each party’s seat share in the Assembly and committee assignments are made based on proposals by party faction leaders (Arias 2008). Costa Rica differs from many Latin American countries in that the executive does not control the legislature, either by formal constitutional powers (Carey 1997) or informal partisan powers. Particularly since the end of the two-party-dominant party system in the late 1990s, and since the president’s party must now form a coalition to win the Assembly’s leadership posts and to pass legislation,[10] the Assembly is a truly powerful actor in the country’s politics. Many Costa Ricans might even call it obstructionist (Gutierrez Saxe and Straface 2008).

We chose the 2010-2014 term for our analysis for several reasons. These deputies were elected in the third election since implementation of the gender quota, so any change in gender dynamics prompted by the large influx of women has had time to subside. Election of a woman president of the country in 2010 is an indication of acceptance of women playing a lead role in Costa Rican politics, and signals that women are viewed as appropriate and capable managers of all policy domains. Finally, standing committee hearings are available on the Assembly webpage, starting with the 2010 session, giving us fine-grained data about participation.[11]

Due to time intensive data acquisition, our analysis is limited to the Economics Issues and Social Issues committees.[12]These committees provide interesting variance for us to exploit in this study. First the percentage of women on the Social Issues committee is the highest, and consistently highest, of any standing committee and women have long held sway on that committee (Heath et al. 2005).In fact, the Social Issues committee is “skewed” with women as the numerically dominant group (Kanter 1977).In contrast, women are still a minority on the Economics committee, though often in the range that Kanter (1977) labels a“tilted”group. The policy jurisdiction of the Social Issues committee is clearly in a traditionally feminine policy domain,[13]thus it is the committee on which women would be expected to be the most involved for reasons discussed in the literature review. By contrast, the Economics committee covers a traditionally masculine policy domain.[14] The Economics committee is also the Assembly’s most prestigious committee and is viewed as a “power” committee.

5. Data and Methods

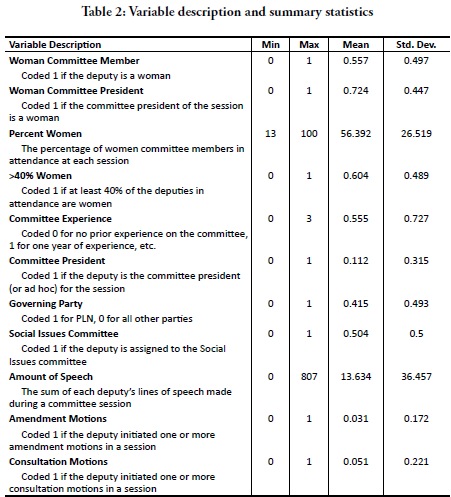

Variables. We create three variables to measure participation in Assembly standing committees. Our dependent variablesare (1) amount of speech, measured by summing each deputy’s lines of speech made during a committee session,[15] (2) whether a deputy proposes a motion to amend a bill (including motions to substitute the subcommittee report for the original bill), and (3) whether a deputy proposes a motion for consultation with a group or organization on a bill, which most often consists of bringing in guest speakers to a committee hearing.[16]

Institutional equality at the level of the chamber does not vary during the time period covered in our analysis, so our main explanatory variable is the sex ratio of members on the committee measured bythe percentage of committee members in attendance that are women.Given our theory, however, we might expect that women need to be a substantial group on a committee in order to ensure that sex barriers to participation have been overcome. Thus, we specify alternative models that control for whether there is a “tilted” ratio in a committee session—that is at least 40% of deputies in attendance are women.[17]To test our hypothesis, we specify an interaction between the sex ratio of the committee (using both the continuous and dichotomous measures)and the sex of the member in the empirical models. We expect that women on the committee will be empowered as the presence of women increases relative to men. These interactions allow us to test whether the composition of the committee impacts men and women differently.

We include several controls in the models to better measure the committee makeup as discussed above. We control for whether the president of the committee is a woman (coded 1 for female committee presidents), and we interact “woman committee president” with “woman committee member” because the literature indicates that men and women may respond differently to a female leader. We include controls for each deputy’s experience on the committee (range 0 – 3 for each previous year of service on the committee),[18] whether the deputy is the committee president for that session (committee president or president ad hoc coded 1 for each session), and whether the deputy is a member of the governing party (coded 1 for PLN deputies). Because committee policy jurisdiction may have an effect on participation we include a control for the committees (Social Issues committee coded 1).(see Table 2 for summary statistics).

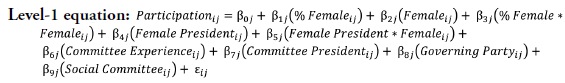

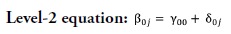

Methods. Given the structure of our data, we use multi-level models with random intercepts to test our hypotheses. Multi-level models allow us to nest multiple observations taken over time within each individual deputy (time nested in individuals). This modeling strategy explicitly takes into account the hierarchical structure of the data and allows the regression parameters to vary across level-2 units, rather than holding these parameters fixed. Alternative strategies that ignore the multilevel structure of the data, such as clustering the data or using fixed-effects models, could lead to incorrect standard errors and increase Type I errors—that is, variables appear to have a significant effect when they do not (Steenbergen and Jones 2002).

The deputy-committee session is our level-1 unit of analysis, and the deputy is the level-2 unit.Treating each deputy in a committee session as a unique observation would be inappropriate given that a particular deputy’s behavior is conditioned on variables relevant to that deputy (e.g. personality, education, occupation, province from which they were elected). A pooled model would assume that each observation is independently identically distributed when we know that it is not.Our level-1 unit of analysis, the committee session, provides variation in the percentage of women in attendance during any given committee hearing, and also variation in the substantive topic discussed during each session.[19] Using the committee session as the level-1 unit of analysis allows us to better capture the variation in individual-level participation and examine how that participation changes under various conditions in committee X on day Y while simultaneously controlling for deputy-level (level-2) effects.

The multi-level model is specified as follows:

where a session-level observation or a level-1 unit i (i = 1, ..., ![]() ) is nested within the individual legislator or level-2 unit j (j = 1, ..., j). Thus, the variables subscripted with ij are the level-1 predictors of the dependent variable and

) is nested within the individual legislator or level-2 unit j (j = 1, ..., j). Thus, the variables subscripted with ij are the level-1 predictors of the dependent variable and ![]() is the level-1 disturbance term. The

is the level-1 disturbance term. The ![]() -parameter denotes the fixed level-2 parameter intercept and the

-parameter denotes the fixed level-2 parameter intercept and the ![]() -parameter is the level-2 disturbance term. Substituting the level-2 equation into the level-1 equation creates the fully specified multi-level model. Note that there are two (or more) levels of intercepts, as well as disturbance terms, in multilevel models. Thus, while the level-2 intercept is fixed, the level-1 intercept varies across level-2 units. As the level-2 equation above shows, the level-1 intercept (

-parameter is the level-2 disturbance term. Substituting the level-2 equation into the level-1 equation creates the fully specified multi-level model. Note that there are two (or more) levels of intercepts, as well as disturbance terms, in multilevel models. Thus, while the level-2 intercept is fixed, the level-1 intercept varies across level-2 units. As the level-2 equation above shows, the level-1 intercept (![]() ) is composed of the fixed level-2 intercept (

) is composed of the fixed level-2 intercept (![]() ) and a random component (

) and a random component (![]() ). We do not detail the full model equations for all analyses, as the subsequent analyses follow this general structure.

). We do not detail the full model equations for all analyses, as the subsequent analyses follow this general structure.

As explained above, we have three dependent variables. To study speechin committee sessions we use a zero-inflated multi-level negative binomial regression analysis because our dependent variable is a count of the total number of lines of speech made by a deputy in a given committee session.[20]For analysis of proposals of motions to amend a bill, and proposals of motions to bring in consultation on a bill we use hierarchical logit modeling because our dependent variable is equal to one if the deputy initiated at least one motion in a session and zero if the deputy initiated no motions.

6. Empirical Results

6.1. Is there gender equality in amount of speech in committee hearings?

A difference of means test shows that on averagewomen speak more than men (16.92 lines of speech per session compared to 9.53, p<0.000, two-tailed, for a difference of means t-test). Additionally, deputies on the Social Issues committee speakmore than deputies on the Economics committee (16.92 compared to 10.29, t-test p < 0.000), regardless of gender.

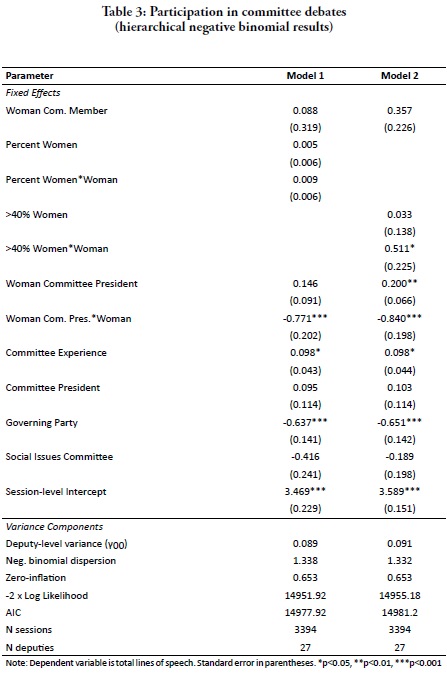

We now turn to multi-level regression analysis to test our hypotheses regarding the impact of the ratio of men to women on participation (see Table 3). Model 1 utilizes a continuous measure of the percentage of women present at a given session of the committee. Model 2 utilizes a dichotomous variable indicating whether the committee session was composed of at least 40% women.The continuous measure of the sex ratio does not have a significant impact on speech (model 1). However, model 2 provides support for our hypothesis, with women participating more in committee discussion when more than 40% of the members in attendance are female. We also find that several of our controls are significant. Deputies with more experience on the committee speak more, deputies from the governing party speak less, and women deputies speak less when a woman is president of the committee.In addition,Model 2 suggests that speech increases for male deputies whena woman is president of the committee for that session (i.e. when female committee president = 1 and female = 0). In future studies it will be important to examine the impact a woman president has on committee participation by male committee members, especially in committees with a stereotypically masculine policy domain. However, we are hesitant to draw strong conclusions from this analysis because for the Economics committee for all cases where the variable “female committee president” equals 1 the same woman was president, so we cannot rule out the possibility that this finding is an artifact of committee relations with that particular woman.[21]The Social Issues committee had a male president for less than 1% of the committee sessions in our dataset, so the finding that male deputies speak more when there is a female committee president may or may not have much substantive meaning for deputies in this committee.

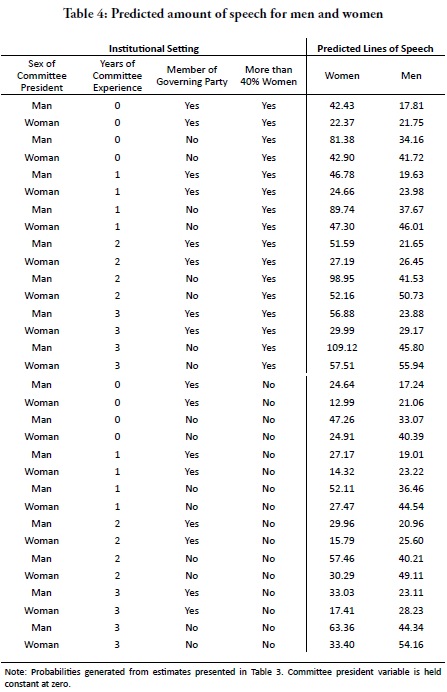

To better depict the impact on speech of having at least 40% women in attendance at a committee session, along with other aspects of deputy background that affect committee composition, we utilize simulations and predicted probabilities (see Table 4). Estimates suggest that the participation of women is impacted greatly by factors such as the committee gender composition, sex of the committee leader, party affiliation, and the deputy’s prior experience on the committee. The best-case scenario for women’s participation during a committee session is when a man is the committee president, the deputy has 3 years of experience on the committee and is not a member of the governing party, and the committee is composed of at least 40% women. Under these conditions, women deputies are expected to contribute about 109 lines of speech to committee debate. This amount is about six times greater than the average amount of speech for women deputies (only 17 lines), suggesting that women’s participation is significantly increased under this contextual setting. The worst-case scenario for women’s participation is when a woman is president of the committee, the deputy has no years of experience on the committee and is a member of the governing party, and there are less than 40% women in attendance. Under these conditions, women deputies are expected to speak only 13 lines during the committee session.

Participation by men is not as greatly affected by changing conditions. The best-case scenario for men’s participation is when a woman is president of the committee, the deputy has at least 3 years of experience on the committee and is not a member of the governing party, and at least 40% of the committee members in attendance are women. Under these conditions, men deputies are expected to contribute about 56 lines of speech to the committee discussion. Under the worst-case scenario—a deputy with no committee experience who is a member of the governing party, with a man committee president and less than 40% women—men are expected to speak about 17 lines. Given that the difference between the worst and best cases for men is 38.70 lines, compared to 96.13 lines for women, the participation of men appears to be less susceptible to changing settings than is the participation of women.

6.2. Is there gender equality inproposal of motions to amend bills?

In addition to speaking in committee hearings, deputies canpropose motions to modify bills.[22]This is fairly rare with an average of just slightly over 3% of deputies proposing at least one motion to amend a bill during any given session.Difference of means tests show that on average women initiate at least one motion to amend a bill more frequently than men (mean for women of 0.042, mean for men of 0.017, p < 0.000).Deputies on the Social Issues committee propose at least one motion to amend a bill more frequently than deputies on the Economics committee (mean for Social Issues of 0.046, mean for Economics of 0.015, p < 0.000).

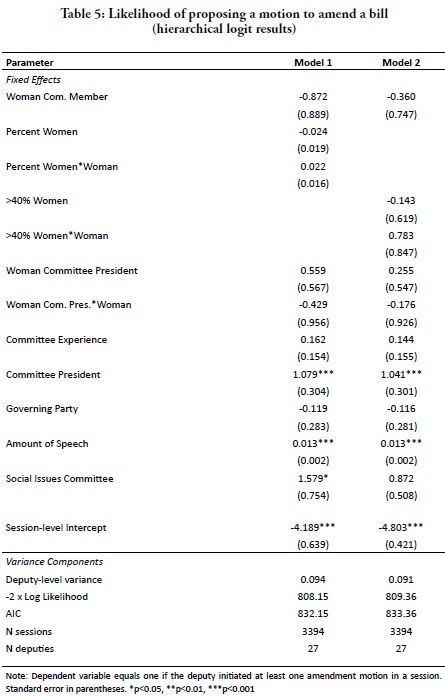

Again, the second step in our analysis is multi-level regression to test our hypotheses regarding the impact on participation of the ratio of men to women (see Table 5). These models include the same variables as our analysis of speech, with the addition of a control for the deputy’s average amount of speech as a proxy for a deputy’s propensity to participate. The logic is that deputies who do not participate through this basic means of participation (speaking during hearings) will be less likely to participate in more complex ways like proposing motions.

In this analysis we do not find the percentage of women in attendance at a session to be significant for predicting participation. However, since the difference of means test indicatedthat women are more active than men in amending bills, this may mean that institutional equality in the chamber is sufficient to create a setting conducive to participation by women, and that institutional equality within the committee is not required for women to be active participants.

Regarding motions to amend bills, we find that different controls are important than what we saw with regard to speech. Prior experience on the committee and party affiliation do not affect the propensity to propose a motion. However, deputies who speak more in the committee are also more active in regard to proposing bill amendments, and the committee president is more likely than other committee members to propose bill amendment motions. Both of these findings indicate that it is important that women be fully incorporated into the legislative body if women are to be able to bring their perspectives to policymaking. Women need to be willing and able to speak, and they need to have as much opportunity as their male colleagues to hold leadership positions in order to engage in substantive representation of women or of other groups.

6.3. Is there gender equality in proposal of motions for consultation?

Deputies can also propose motions for consultation on a bill. These motions typically are to bring in guest speakers.Deputies on the Social Issues committee, for example, might propose a motion for consultation with the Ministry of Health, the National Insurance Institute, or education interest groups.Deputies on the Economics committee might propose a consultation from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Foreign Trade, banking groups or other business groups.The opportunity to give a group or executive branch agency the ability to articulate its position on a bill is potentially very important for determining which groups in society get their views heard in the policy-making process (see Taylor-Robinson and Ross 2011). Thus it is potentially important for representation of diverse interests that women, now that they have made numerically large in-roads into Costa Rican politics, make use of their capability to provide groups with this chance at representation.

Difference of means tests show thaton average women initiate at least one consultation motion more frequently than men (mean for women of 0.059, mean for men of 0.042, p < 0.05). Deputies on the Social Issues committee propose at least one consultation motion more frequently than deputies on the Economics committee (Social Issues mean of 0.069, Economics committee mean of 0.033, p < 0.000).

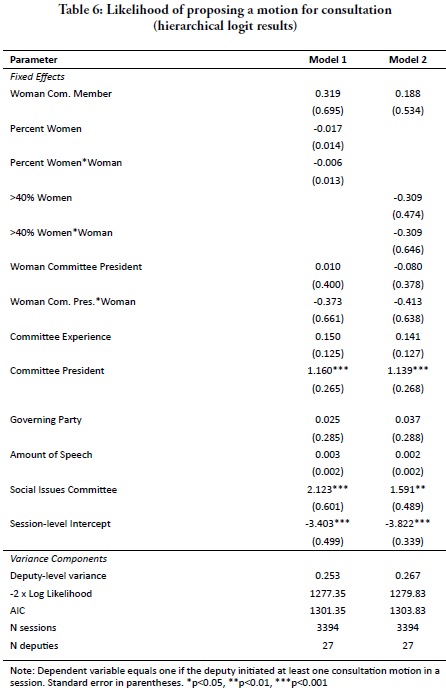

The dependent variable in our multi-level regression is a dummy variable that equals one if the deputy initiated at least one motion for consultation during a given session (seeTable 6).As with the analysis of amendment motions, the ratio of women to men present at a committee hearing does not have a significant impact on the propensity to propose a consultation motion. It is noteworthy, however, that thecontrol for committee president is again statistically significant, highlighting the importance of women holding leadership positions.

7. Conclusions

This paper explores whether women are able to be full and equal participants in legislative committees, not with a focus on substantive representation of women’s interests, but participation on any topic. The Economics and Social Issues committees provide an interesting test because they anchor stereotypically masculine and feminine policy domains, and women have long dominated the membership and leadership of Sociales, but areusually a minority and rarely leaders on Económicos.

Difference of means tests show that women on these committees in the Costa Rican legislature are more active than men, so clearly women are participating in their committees. However, “institutional equality” within a committee, which we operationalize as women composinga large percentage of committee members in attendance,does not appear to be the driving force behind women’s equal participation. With regard to quantity of participation in committee debates, we find that women do participate more when at least 40% of the deputies present at the session are women. However, near gender balance on the committee does not affect propensity to initiate motions to amend bills or to invite consultations. Other aspects of committee composition, which we viewed as controls while we focused on gender composition, also influence participation. Regarding speech, deputies with experience on the committee anddeputies from opposition parties are more active, and women are less active in the presence of a woman committee president. Deputies who hold the committee president post are more active in terms of motions to amend a bill or consultation motions. Because institutional equality for women in committees does not appear to explain equal participation by women, institutional equality in the chamber overall, possibly paired with a societal change in attitudes about the appropriate role of women in politics, may be what is associated with gender equal participation by legislators in committees, though more studies with data over a longer time frame are obviously needed to directly test this.

The “distribution of power,” a gendered aspects of institutions listed by Acker(1992), has opened up in Costa Rica, with many women present in the legislature, on a more equal playing field with menbecause all deputies lack seniority, and as many women as men hold committee leadership posts. This research suggests that it matters that women be present in the chamber in large numbers. Our findings also indicate that it is importantthat women have an equal opportunity to be committee presidents because committee presidents are more likely than other committee members to propose bill amendments and motions for consultation. In addition, the gendered nature of Costa Rica’s legislature may be dampened by committee meetings that occur outside of media and public scrutiny and where “hierarchical, authoritative relationships ... and interpersonal dynamics involving coercion and manipulation” (Reingold 2008: 132) are not the norm. Speech in these committee hearings typically indicates a back-and-forth between equals, normally delivered in respectful tones across the sexes and generally across parties.

In sum, this study indicates that more women – in the chamber and above a threshold that Kanter called a “tilted group” in committees – appears to be associated with women being equal participants in debates. But it is also important that women be leaders when we operationalize committee participation in forms other than speechmaking. Getting women into the legislature is a necessary first step, but having more than a token woman on stereotypically masculine policy domain committees, and having women in leadership posts, can also affect participation.

Speech in committee debates, as well as both types of motion activity, can have an important impact on representation. Future research should explore if committee speeches or motions by women and men differ in content (e.g., different concerns about bills, or whose opinion should be heard by the committee). It appears that women will be more likely to get to engage in substantive representation – of women or of other groups’ interests – if they hold leadership posts, and if women work in a legislative chamber that on many dimensions reflects institutional gender equality.

Bibliography

Acker, Joan(1992). “From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions”.Contemporary Sociology 21(5): 565-569.

Alemán, Eduardo(2006). “Policy Gatekeepers in Latin American Legislatures”.Latin American Politics and Society 48(3): 125-155.

Aparicio, Javier and Joy Langston (2009). “Committee Leadership Selection without Seniority: The Mexican Case”.Working Paper, CIDE.

Arias Ramirez, B. (2008). “Estudio Comparativo de Normativa Parlamentaria”.Estado de la Nación: Decimocuarto Informe Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible. www.estadonacion.or.cr

Barnes, Tiffany D. (2014). “Women’s Representation and Legislative Committee Appointments: The Case of the Argentine Provinces”.The Kellogg Institute for International Studies Working Paper Series. Working Paper #397, March 2014. https://kellogg.nd.edu/publications/workingpapers/WPS/397.pdf

Beckwith, Karen(2005). “A common language of gender?”Politics & Gender 1: 128-137.

Bicquelet, Aude, Albert Weale and Judith Bara(2012). “In a Different Parliamentary Voice? Politics & Gender 8(1): 83-121.

Bratton, Kathleen A. (2005). “Critical Mass Theory Revisited: The Behavior and Success of Token Women in State Legislatures”.Politics & Gender 1: 97-125.

Broughton, Sharon and Sonia Palmieri (1999). “Gendered Contributions to Parliamentary Debates: The Case of Euthanasia”.Australian Journal of Political Science 34(1): 29-45.

Calvo, Ernesto. forthcoming. Legislator Success in Fragmented Congresses: Plurality Cartels, Minority Presidents, and Lawmaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cammisa, Anne Marie and Beth Reingold (2004). “Women in State Legislatures and State Legislative Research: Beyond Sameness and Difference”.State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 4(2): 181-210.

Carey, John M. (1997). “Strong Candidates for a Limited Office: Presidentialism and Political Parties in Costa Rica”. In Scott Mainwaring and Matthew Soberg Shugart (eds.)Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press,pp.199-224.

Catalano, Ana (2009). “Women Acting for Women? An Analysis of Gender and Debate Participation in the British House of Commons 2005-2007”.Politics & Gender 5(1): 79-98.

Chaney, Paul(2006). “Critical Mass, Deliberation and the Substantive Representation of Women: Evidence from the UK’s Devolution Programme”.Political Studies 54: 691-714.

Childs, Sarah and Julie Withey (2004). “Women Representatives Acting for Women: Sex and the Signing of Early Day Motions in the 1997 British Parliament”.Political Studies 52(3): 552-564.

Darcey, R. (1996). “Women in the State Legislative Power Structure: Committee Chairs”.Social Science Quarterly 77: 888-898.

Devlin, Claire and Robert Elgie (2008). “The Effect of Increased Women’s Representation in Parliament: The Case of Rwanda”.Parliamentary Affairs 61(2): 237-254.

Diamond, Irene(1977). Sex Roles in the State House. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dolan, Kathleen and Lynne E. Ford (1997). “Change and Continuity among Women State Legislators: Evidence from Three Decades”.Political Research Quarterly 50(1): 137-151.

Duerst-Lahti, Georgia (2002). “Knowing Congress as a Gendered Institution”. In Cindy Simon Rosenthal (ed.)Women Transforming Congress (Vol. 4). University of Oklahoma Press, pp.20-49.

Frisch, Scott A. and Sean Q. Kelly (2003). “A Place at the Table: Women’s Committee Requests and Women’s Committee Assignments in the U.S. House”.Women & Politics 25(3): 1-26.

Friedman, Sally (1996). “House Committee Assignments of Women and Minority Newcomers, 1965-1994”.Legislative Studies Quarterly 21(1): 73-81.

Furlong, Marlea and Kimberly Riggs(1996). “Women’s Participation in National-Level Politics and Government: The Case of Costa Rica.” Women’s Studies International Forum 19(6): 633-643.

Gutiérrez Saxe, M. and F. Straface (eds.)(2008). ¿Democracia Estable Alcanza? Analisis de la Gobernabilidad en Costa Rica. Inter-American Development Bank and Estado de la Nación: Publicaciones Especiales Sobre el Desarrollo.

Hall, Rick L. (1996). Participation in Congress. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Heath, Roseanna, Leslie Schwindt-Bayer and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson(2005). “Women on the Sidelines: Women’s representation on committees in Latin American legislatures”.American Journal of Political Science 49(2): 420-436.

Kanter, Rosabeth M. (1977). “Some Effects of Proportions on Group Life: Skewed Sex Ratios and Responses to Token Women”.American Journal of Sociology 82(5): 965-991.

Karpowitz, Christopher F., Tali Mendelberg and Lee Shaker(2012). “Gender Inequality in Deliberative Participation”.American Political Science Review 103(3): 533-547.

Kathlene, Lyn(1994). “Power and Influence in State Legislative Policymaking: The Interaction of Gender and Position in Committee Hearing Debates.” American Political Science Review 88(3): 560-576.

Kenney, Sally J. (1996). “New Research on Gendered Political Institutions”.Political Research Quarterly 49: 445-466.

Long, J. Scott, and Jeremy Freese. 2006. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Murray, Rainbow (2010a). “Second Among Unequals? A Study of Whether France’s ‘Quota Women’ are Up to the Job”.Politics & Gender 6(1): 93-118.

Murray, Rainbow(2010b). “Linear Trajectories or Vicious Circles? The Causes and Consequences of Gendered Career Paths in the National Assembly”.Modern and Contemporary France 18(4): 445-459.

Pearson, Kathryn and Logan Dancey(2011). “Elevating Women’s Voice in Congress: Speech Participation in the House of Representatives”.Political Research Quarterly 64(4): 910-923.

Pearson, Kathryn and Logan Dancey (2012). “Speaking for the Underrepresented in the House of Representatives: Voicing Women’s Interests in a Partisan Era”.Politics & Gender 7(4): 493-519.

Piscopo, Jennifer M. (2011). “Rethinking Descriptive Representation: Rendering Women in Legislative Debates”.Parliamentary Affairs 64(3): 338-372.

Reingold, Beth(2008). “Women as Officeholders: Linking Descriptive and Substantive Representation.” In Christina Wolbrecht, Karen Beckwith and Lisa Baldez (eds.)Political Women and American Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 128-147.

Rosenthal, Cindy Simon(1997). “A View of Their Own: Women’s Committee Leadership Styles and State Legislatures”.Policy Studies Journal 25: 585-600.

Rosenthal, Cindy Simon(2005). “Women Leading Legislatures: Getting There and Getting Things Done.” In Sue Thomas and Clyde Wilcox (eds.)Women and Elective Office: Past, Present, and Future, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press,pp.197-212.

Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. (2005). “The Incumbency Disadvantage and Women’s Election to Legislative Office”.Electoral Studies 24(2): 227-44.

Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. (2006). “Still Supermadres? Gender and the Policy Priorities of Latin American Legislators”.American Journal of Political Science 50(3): 570-85.

Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. (2010). Political Power and Women’s Representation in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Steenbergen, Marco R. and Bradford S. Jones (2002). “Modeling Multilevel Data Structures”.American Journal of Political Science 46(1): 218-37.

Swers, Michele L. (2001). “Research on Women in Legislature: What Have We Learned, Where Are We Going?” Women & Politics 23(1-2): 167-85.

Swers, Michele L. (2002). The difference women make: The policy impact of women in Congress. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Swers, Michele L. (2014). “Unpacking Women’s Issues: Gender and Policymaking on Health Care, Education, and Women’s Health in the U.S. Senate.” In Maria C. Escobar-Lemmon and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson (eds.)Representation: The Case of Women. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.158-182.

Taylor-Robinson, Michelle M. and Roseanna M. Heath(2003). “Do Women Legislators Have Different Policy Priorities than Their Male Colleagues: A Critical Case Test”.Women & Politics 24(4): 77-101.

Taylor-Robinson, Michelle M. and Ashley Ross(2011). “Can Formal Rules of Order be Used as an Accurate Proxy for Behavior Internal to a Legislature? Evidence from Costa Rica”.Journal of Legislative Studies 17(4): 479-500.

Thomas, Sue(1994). How Women Legislate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Towns, Ann (2003). “Understanding the Effects of Larger Ratios of Women in National Legislature: Proportions and Gender Differentiation in Sweden and Norway”.Women & Politics 25(1/2): 1-29.

Walsh, Denise (2012). “Party Centralization and Debate Conditions in South Africa.” In Susan Franceschet, Mona Lena Krook and Jennifer M. Piscopo (eds.)The Impact of Quota Laws. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 119-135.

Zetterberg, Pär(2008). “The downside of gender quotas? Institutional constraints on women in Mexican state legislatures”.Parliamentary Affairs 61(3): 442-460.

* Artículo recibido el 26 de setiembre de 2013 y aceptado para su publicación el 15 de agosto de 2014.

* Research Associate, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University, kendallfunk@tamu.edu.

** Professor, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University, m-taylor11@pols.tamu.edu.

[1] Kanter’s study was of corporate settings.

[2] The final group type in Kanter’s study is “balanced” with a 60/40 to 50/50 ratio. In that situation she predicts that “Majority and minority turn into potential subgroups which may or may not generate actual type-based identifications. Outcomes for individuals in such a balanced peer group, regardless of type, will depend on other structural and personal factors, including formation of subgroups or differentiated roles and abilities” (1977: 966).

[3] Recent coverage of the Texas state legislature highlights women’s frustration with not being recognized to speak on the floor, and Honduran women deputies voiced similar complaints to one of the authors in interviews. But interview data in Zetterberg’s (2008: 453) study of quota women in Mexican state legislature found “committee work as a forum for mutual compromise.”

[4] Interviews with women legislators in Latin American countries find that they do not describe their job as being limited to stereotypically feminine policy areas. The diversity of women legislators’ interests makes them appear very similar to their male colleagues (Furlong and Riggs 1996; Schwindt-Bayer 2006, 2010).

[5] In some legislatures women are found to be equitably represented across different types of committees: Friedman’s (1996) study of the U.S. Congress by the 1970s, Dolan and Ford’s (1997) study of U.S. state legislatures, Devlin and Elgie (2008) for Rwanda with its very effective gender quotas and its status as the only national legislature with more than 50% women (Inter-Parliamentary Union http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm).

[6] Deputies may also be more inclined to participate if they have an education or work background that overlaps with the policy purview of the committee. We do not control for education or career background in the models presented here due to multicollinearity with the committee experience variable. Because coding the relatedness of each deputy’s education and career to their committee assignment is more subjective than measuring years of experience on the committee we opt to control for the “background” of the deputy via committee experience.

[7] The quota was not implemented until after the Supreme Elections Tribunal passed rules to sanction non-compliance in 1999. In 2009 a parity law requiring zipper ballots was passed, which were implemented in the 2014 election (www.quotaproject.org).

[8] Smaller parties complete the legislature’s membership: Unidad Social Cristiana’s (PUSC) caucus is comprised of 17% women. The Accesibilidad Sin Exclusion (PASE) caucus is 25% women. Three parties won one seat each (Renovación Costarricense, Frente Amplio, and Restauración Nacional), and a man occupies each of these seats.

[9] One man in our dataset had served a pervious term in the Assembly.

[10] In the second year analyzed here the PLN fumbled negotiations for majority support for its chamber leadership candidate slate, and a coalition of all other parties in the Assembly won the chamber Directorate election.

[11] Data are available at www.asamblea.go.cr.

[12] Our data include committee hearings from May 2010 to December 2012, which covers 2 ½ years of the four-year term. In total, we coded men and women’s participation for 375 committee hearings.

[13] The Social Issues committee is in charge of issues related to labor, social security, health, social protection and education (Art.66 p.38 Reglamento de laAsamblea Legisltiva, Acuerdo Legislativa # 399, Nov.29, 1961, modified Feb.27, 2012).

[14] The jurisdiction of the Economics committee covers economics, commerce, industry, the common market and integration (Art.66, p.38).

[15] We did not count procedural speech (e.g., introduction of speakers, announcing the order of business for a session, presentation of committee correspondence, vote outcomes). Excluding procedural speech means that our measure of speech is comparable for deputies who hold leadership posts in the committee and deputies who do not.

[16] In some cases a deputy proposed more than 1 amendment motion or more than 1 motion for consultation within a single session. However, we utilize a binary dependent variable where 1 indicates that the deputy initiated one or more motions of a particular type during the committee session and 0 indicates that the deputy initiated no motions of that type during the session because proposing motions is rare.

[17] Committees differ in the percentage women assigned to the committee (see Table 1), but committee assignments do not capture the variance in committee composition from session to session. This is particularly interesting for the Economics Committee, where overall membership never exceeds this 40% women threshold, but in some sessions 60% members in attendance were women. See Karpowitz et al. (2012) for experimental findings about now gender composition of a 5-person group affects speaking by women.

[18] One deputy had served previously in the Assembly, and he had served on the same committee in the past, so that deputy is coded 3 for committee experience.

[19] Future work should explore whether the topic of the bill under discussion, the sex or party affiliation of the bill sponsor, or number of bill co-sponsors impact participation. We thank Harvey Tucker for these suggestions.

[20]Negative binomial is appropriate because moving from 0 or 1 lines of speech to several is a different accomplishment for a deputy than moving from 100 lines of speech to 110 lines of speech, and a negative binomial count model accounts for this over-dispersion (Long and Freese 2006). The model is zero-inflated because 66% of the observations are equal to zero for this variable. Analysis was conducted in R using the glmmADMB package (http://glmmadmb.r-forge.r-project.org) for hierarchical negative binomial models and the arm package (http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=arm) for hierarchical logit models.

[21] In contrast, three different women held the Social Issues committee president post from 2011-2013, and several women served as the president ad hoc.

[22] Where more than one deputy co-sponsored a motion, all deputies whose names were listed as sponsors of the motion received credit for initiating the motion.