Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política

On-line version ISSN 1688-499X

Rev. Urug. Cienc. Polít. vol.23 no.spe Montevideo Dec. 2014

BEYOND HEARTH AND HOME: FEMALE LEGISLATORS, FEMINIST POLICY CHANGE, AND SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION IN MEXICO*

Más allá del hogar: Las legisladoras, el cambio feminista en las políticas y la representación sustantiva en México

Jennifer M. Piscopo**

Abstract: This paper uses the Mexican case to explore outstanding questions in the connection between women’s descriptive representation (that is, women’s numerical presence in the legislature) and women’s substantive representation (that is, women’s policy interests). Consistent with previous work in Latin America, I find that electing women indeed diversifies the legislative agenda, and that female legislators –rather than male legislators– author proposals with feminist understandings of women’s rights and roles. These trends are robust across Mexico’s ideologically-organized political parties, indicating that feminist advocates should care about electing leftists and women. That is, rightist women are still more progressive than rightist men. Finally, I make a case for unpacking the relationship between women, hearth, and home, and eliminating the conflation of “women’s interests”with children.

Keywords: Mexico, women legislators, descriptive representation, substantive representation

Resumen: Este artículo utiliza el caso mexicano para explorar temas pendientes en la conexión entre la representación descriptiva de las mujeres (es decir, la presencia numérica de las mujeres en la legislatura) y la representación sustantiva de las mujeres (es decir, las políticas que responden a los intereses de las mujeres). De acuerdo con trabajos previos sobre América Latina, encuentro que la elección de mujeres hace que la agenda legislativa sea más diversa, y también que las legisladoras –más que los legisladores– presenten propuestas que se sustentan en perspectivas feministas sobre los derechos y roles de las mujeres. Estas tendencias se mantienen a través de todos los partidos políticos mexicanos que se organizan ideológicamente, indicando que las activistas feministas deben preocuparse por que se elijan representantes de izquierda y mujeres. Es decir, las mujeres de derecha son aun más progresistas que los hombres de derecha. Para concluir, planteo la necesidad de desentrañar la relación entre las mujeres y el hogar y de eliminar la fusión de “intereses de las mujeres” con la niñez.

Palabras clave: México, legisladoras, representación descriptiva, representación sustantiva

1.Introduction

The dramatic increase in women’s numerical presence in legislatures across Latin America raises the possibility that qualitative improvements in policy and governance will follow. These expectations are grounded in normative discourses that see women –by virtue of their different social positions and roles– as introducing new perspectives to policy debates: the more diverse the legislative body, the more responsive and inclusive the decisions. In the words of Argentine activists who supported the electoral quota law that compelled parties to nominate women, “With few women in politics, women change, but with many women in politics, politics changes” (Marx, Borner, and Caminotti 2007:61).

For scholars of gender and politics, this connection is studied as the link between women’s descriptive representation (that is, women’s numbers in legislative office) and women’s substantive representation (that is, women’s policy interests). Researchers have explored whether Latin American female legislators are more likely than male legislators to support policies related to women’s interests, conceived as women’s rights policies or social policies such as education and health. Generally, findings have been positive: female legislators do change politics by supporting equal rights legislation and social welfare policies (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008; Htun, Lacalle, and Micozzi 2013; Miguel 2012; Schwindt-Bayer 2010). Yet none of these studies have included the Mexican case, despite a highly successful electoral quota law that has raised women’s descriptive representation to over 30 percent. This study offers the first quantitative assessment of the descriptive-substantive connection in the Mexican Congress.

The Mexican case also provides an opportunity to answer some outstanding theoretical and methodological questions. First, how can scholars parse the causal effects of gender identity versus party membership? Scholars have debated whether women’s policy preferences can be attributed to their sex or to their adherence to party platforms (Htun and Powers 2006; Piscopo 2011a). In the case of Mexico, two of the major three parties have staked clear, consistent ideological positions: the PartidoAcciónNacional(PAN) on the right, advocating economic neoliberalism and social conservatism, and the PartidoRevolucionarioDemocrático(PRD) on the left, advocating state-led social welfare regimes that benefit the working class and other marginalized groups. Looking at substantive representation within the Mexican political parties offers an opportunity to explore whether rightist women (female panistas)still stake out progressive positions on women’s issues.

Second, and related, how can scholars measure women’s substantive representation without neglecting the diversity of identities and preferences within women as a group? Celis and Childs (2012)have asked what scholars of women’s substantive representation should “do” with conservative women. That is, the standard conceptualization and operationalization of women’s interests has examined feminist policy change, ignoring instances wherein female legislators support policies that restrict women’s rights or protect male privilege. Yet under a strict definition of women’s substantive representation –that women’s interests are advocated for in policy debates– there appears no reason to exclude, ex ante, conservative visions. After all, as a female panistacommented in an interview, women who identify as housewives have interests in economic policies that support women’s domestic –as opposed to formal sector– work.[1] This paper thus takes a “values-neutral” approach to substantive representation, comparing female legislators who represent feminist policy change (proposals that would advance women’s rights and roles beyond those associated with hearth and home) to female legislators who represent non-feminist policy change (policies that shape women’s rights and roles in relation to hearth and home).

Third, and finally, can male legislators substantively represent women? The causal factor linking descriptive representation to substantive representation is legislators’ gender identity. Consequently, male legislators are not typically theorized as advocates for women’s interests. Yet this theoretical formulation confronts an empirical reality: male legislators’ may represent women less than female legislators, but they do not neglect women’s interests all of the time (Htun, Lacalle, and Micozzi 2013; Piscopo 2011a; Schwindt-Bayer 2010).When, then, are men considered women’s interests advocates? This paper explores this question by attending more carefully to the frequencies of men’s and women’s advocacy of feminist versusnon-feminist policy proposals, as well as proposals related to child wellbeing.

This paper thus uses the Mexican case to address outstanding questions about which legislators undertake substantive representation and which policies count as substantive representation. I ask the following research questions: Does women’s descriptive representation enhance women’s substantive representation? Does gender identity (as proxied by sex) or party ideology best explain legislators’ policy preferences on women’s interests? Finally, how much evidence exists for substantive representation that is non-feminist and/or undertaken by men, and what are the theoretical implications of these trends? I focus on substantive representation as process, which Franceschet and Piscopo (2008) conceptualize as alterations to the legislative agenda (as opposed to substantive representation as outcome, which consists of policy change). I operationalize substantive representation as bill introduction, using quantitative data from the Mexican Chamber of Deputies between 1997 and 2012. I supplement the statistical analysis with qualitative data from fifteen field interviews conducted with female legislators from Mexico’s three largest partiesin December 2009. At the time, interviewees were current members of the Chamber of Deputies or Senate, or had served at least one term in either chamber between 1997 and 2009.[2]

Consistent with other studies from Latin America, I find that electing women indeed adds women’s interests to the legislative agenda. While right parties are less likely to represent women overall, female deputies from the right and leftare more likely than their male colleagues to represent women’s interests. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of substantive representation is feminist.

Related,my coding scheme for women’s interests shows that researchers must untangle the complicated nexus between women, hearth, and home. When feminist proposals are separated from non-feminist proposals, and non-feminist proposals are divided between women, on the one hand, and children, on the other, significant differences between male legislators’ and female legislators’ bill introduction emerge. Male legislators, particularly those on the left, do propose some feminist bills, but many male legislators abandon an explicit focus on women in favor of an explicit focus on children. This abandonment is most notable among men on the right. These findings suggests that previous studies, which have not divided women’s interests in this way, may have over-estimated the participation of male legislators in feminist substantive representation. That is, when a single “women’s interest” measure includes proposals addressing women and children,differences in female legislators’ and male legislators’ approaches to substantive representation are overlooked.

I build this argument as follows. First, I present background data on women’s descriptive representation and legislative politics in Mexico. Second, I analyze overall trends in women’s substantive representation, followed by an examination of the bills’ content –that is, whether substantive representation means the advocacy of feminist proposals, non-feminist proposals, or proposals focused on children. I conclude that female legislators are largely responsible for placing feministwomen’s interests on theagenda.

2. Quotas, elections, and descriptive representation in Mexico

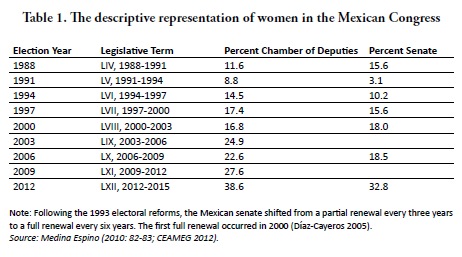

Mexico has applied a gender quota law for elections to the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate since 2002 (Baldez 2008). A 30 percent quota was adopted as part of the 1996 electoral reform as a suggestion for the political parties. Reforms made this recommendation mandatory in 2002 and raised the quota threshold to 40 percent in 2008. As shown in Table 1, when the 30 percent mandatory quota applied for the first time in 2003, women’s descriptive representation in the Chamber of Deputies climbed from 16.8 percent to 24.9 percent. After the 40 percent quota applied in 2008, this figure rose to 27.6 percent following the 2009 elections and to 38.6 percent following the 2012 elections. The quota has similarly affected Senate elections: though the 2006 elections, in which the 30 percent quota applied, resulted in the election of only 18.5 percent women, the 2012 elections, in which the 40 percent quota applied, resulted in the election of 32.8 percent women (Medina Espino 2010:82-83; CEAMEG 2012).

The interaction of the quota law with electoral rules and parties’ strategic use of candidate nominations explains why, progress notwithstanding, the quota has always been under-filled. The 500-seat Mexican Chamber of Deputies renews ever three years, and the 128-seat Senate renews every six years, so each Senate sits for two consecutive three-year terms. The Mexican Constitution prohibits immediate reelection to the same post, eliminating incumbents.[3]

In the Chamber of Deputies, 300 legislators are selected via plurality rule in single-member districts (SMDs) and 200 legislators are selected via closed list proportional representation (PR) in five 40-seat districts (circunscripciones) that encompass several states. The Senate employs closed-list PR, with 32 members chosen from a nationwide list and 96 members chosen from state-level lists. For the state-level races, parties present lists of two candidates in rank-order: the party receiving the most votes (the “majority party”) elects both candidates, and the second-place party (the “minority party”) elects thetop candidate. In this manner, each Mexican state is represented by three senators.

For all races, the 2002 quota law applied to propietario (primary) candidates rather than suplente (substitute) candidates. The law also included a placement mandate for the PR lists, prohibiting parties from clustering women’s names in the unelectable positions at the bottom. Both factors improve quota compliance, although the placement mandate cannot prevent parties from placing women second on the state-level lists for the Senate races. Thisstrategy partially explains the quotas’ under-fulfillment in the Senate: women are typicallyranked second on state-level lists, and thus elected from the majority party, but not the minority party. Further, the 2002 law exempted parties choosing candidates via direct primaries from fulfilling the quota. Baldez (2008) argues that this provision unintentionally encouraged Mexican political parties to implement primaries, allowing Mexican parties to avoid the quota for both chamber and senate races. Finally, while the quota stipulates that 40 percent of all nominees for the lower-house SMDs must be female, researchers have shown that parties will run women in non-competitive districts –that is, districts where they have no expectations of winning (Langston and Aparicio 2011).

Thus, electoral rules and nomination strategies offer Mexican parties opportunities to undercut the quota. The election of women has improved over time due largely to female party members’ ability to pressure the party leadership, as well as extensive monitoring from civil society organizations and the media (Piscopo 2011b). Pivotal for the 2012 elections were rulings by Mexico’s federal electoral courtthat eliminated the primary exemption and stipulated that propietario-suplentepairingsmust be of the same sex. The latter decision followed the 2009 post-election scandal of the so-called “Juanitas” –sixteen female propietarios who resigned their seats in favor of their male suplentes (Piscopo 2011b; Hinojosa 2012). A 40 percent quota with fewer loopholes, combined with greater publicity and media pressure, contributed to the Mexican quota law’s greatest numerical success in the 2012 elections.

3. Women and the Mexican Congress

The legislative behavior of Mexican women elected under quotas has not received as much attention as the adoption and implementation of quotas themselves (Baldez 2008; Bruhn 2003; Piscopo 2011b). The few quantitative studies of women’s substantive representation in Latin America have not included Mexico as a case (Franceschet and Piscopo2008; Htun, Lacalle, and Micozzi, 2013; Miguel 2012; Schwindt-Bayer 2006; 2010). This research has, however, sketched a picture of women’s substantive representation in the region. Across Latin America, female legislators are more likely than male legislators to support feminist policies that liberalize access to contraception and abortion, protect women from sexual violence, and expand women’s political and economic rights. Further, consistent with theoretical expectations that associate women with social justice, female legislators are seen attending to marginalized and disadvantaged populations more than male legislators.

Insights about Mexican female legislators specifically have come from qualitative studies that examine specific gender policy areas. For example, Stevenson (1999) found that female legislators advocated for adopting gender quotas and criminalizing marital rape. Female legislators also crafted the laws creating the bicameral Comisión de Equidad y Géneroin 1998 and the InstitutoNacional de lasMujeres(InMujeres) in 2003 (Piscopo 2011a). Further, each congressional term, female legislators have agreed upon gender policy goals, including ending workplace discrimination, combating family violence, improving parental involvement in childcare, and eliminating sexism more broadly (Tarrés 2006). Thus, while case study evidence exists that female legislators undertake substantive representation in a specifically feminist direction, no quantitative studies have examined these overall patterns.

Other quantitative studies of the Mexican Congress have also neglected women’s role, focusing more on legislative behavior and party discipline (Casar 2011; Díaz-Rebolledo 2005; González Tule 2007; Kerevel 2009; Langston 2010; Nacif 2003; Nava Polina and YáñezLópez 2003). Nonetheless, these studies offer insights for studying women’s substantive representation. First, since the onset of divided government in 1997 –the year in which the PartidoRevolucionarioInstitucional(PRI) lost its congressional majority for the first time since 1934– the Mexican Congress has experienced a direct increase in individual legislators’ bill introduction (Nava Polina and YáñezLópez 2003; Kerevel 2009). Competitive electoral democracy in Mexico has allowed bill introduction to become a “fairly open process”: more legislators author proposals, and legislators from different parties frequently author proposals similar in theme but reflective of their party’s particular solutions (Nacif 2002:26-35). Consequently, while party ideology remains an important determinant of bill content, female legislators –and their male counterparts– can voice preferences by authoring proposals in specific policy areas.

Second, party leaders control roll-call voting, but not necessarily bill introduction. The constitutional prohibition on immediate reelection makes for highly disciplined political parties: following their congressional terms, Mexican legislators seek high prestige posts in state governments or on parties’ steering committees, giving governors and party bosses significant control over politicians’ careers (Weldon 2004; Langston 2010). However, party leaders in congress typically focus on pushing favored proposals through commissions, attaching the appropriate amendments, and ensuring treatment in the plenary (Nacif 2002). Deputies are free to introduce bills; ones that are undesirable or unimportant, from the perspective of the leadership, simply do not advance, and party discipline is assessed primarily through roll call votes (González Tule 2007; Nacif 2002; Weldon 2004).

Further, when it comes to women’s interest proposals, female legislators perceive a distinct gender bias not at the bill introduction stage, but at the policy passage stage. For example, a former PRI leader, recalling her work on an anti-sexual harassment bill, remembered how male legislators dismissed the idea: “I said to the men, do not be obnoxious, don’t laugh at the women, take them seriously.”[4] Passing anybill depends on party leaders’ negotiations and priorities, and women’s interest bills may face additional, gendered hurdles. Consequently, examining policy passage will not paint an accurate portrait of female legislators’ contributions to the Congress. In the Mexican context, bill introduction providesa better measure of individual legislators’ policy preferences, especially on women’s interests.

What factors, then, shape Mexican legislators’ bill introduction strategies? In the lower chamber, for instance, SMD deputies introduce more proposals when compared to PR deputies, and SMD deputies target their constituencies with particularistic benefits (Keverel 2009). Committee assignments can also influence preferences, as Langston and Aparicio (2009) show that female legislators are more frequently assigned to committees addressing the softer, less-prestigious policy areas (such as health and education), rather than the harder, more prestigious policy areas (such as intelligence and defense). Connecting the two trends, Ugues, Medina Vidal, and Bowler (2012) found that SMD deputies are typically assigned to committees dealing with particularistic policies (such as agriculture), when compared to PR deputies, who are typically assigned to committees addressing universalistic policies (such as women or the environment).[5]How these institutional incentives shape women’s substantive representation, however, remains unclear. On the one hand, female SMD deputies could support gender reforms in order to reward their constituents: cash transfers to female-household heads, for instance, could be particularistic benefits targeted to women in low-income districts. On the other hand, gender policies are generally softer and universalistic, indicating an active role for female deputies and senators generally and female PR deputies particularly.

Legislators’ policy preferences could further depend on membership in the president’s party andtheir relationship with the party leadership (Weldon 2004; Langston 2010).Party leaders may prefer that legislators focus exclusively on supporting or opposing the executive’s agenda. Party bossesmay also sanction legislators for authoring women’s interest bills, especially if these proposals challenge sacred Mexican institutions such as the family and the Church. Yet female legislators –especially deputies elected from PR lists– conceive of women as a constituency. Interviewees from all three parties frequently attributed their nomination to prominence attained via service in women’s civil society organizations or the party’s women’s wing.[6] As one female PRD deputy wryly observed, “I am handicapped and I am female, so I check both boxes and respond to both.”[7] Quota laws may heighten this effect by creating mandates for women to represent women (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008). Female legislators may therefore write women’s interest bills to maintain ties with female constituents and women’s organizations. And party leaders, knowing they can block unfavorable initiatives at the policy passage stage, can obtain electoral benefits by “allowing” such legislation to be introduced.

Additionally, two institutional structures support female legislators who wish to advocate for women’s rights. The bicameral Comisión de Equidad y Género (CEG) coordinates female deputies and female senators from all parties into a women’s caucus. Even though the CEG constitutes a universalistic policy committee and thus attracts more PR deputies (Ugues, Medina Vidal, and Bowler 2012:106), all female legislators see the CEG as an important avenue for substantive representation. A former PRD deputy noted that, “When I was elected, everyone wanted to occupy seats on the Commission on Gender and Equity, so I had to go elsewhere, but I continued to be an ally… the majority of initiatives that I introduced were discussed in the Commission on Equity and Gender, because they dealt with gender policy.”[8] A current PAN deputy explained, “I chose the Commission on Equity and Gender because I knew there was an agenda pending” and a longtime PRI congresswoman observed, “We all go to the CEG meetings, even if we are not members.”[9]Thus, while technically a softer committee (Langston and Aparicio 2009), the CEG is not entirely marginalized. The body enjoys substantial review powers and holds regular, joint meetings with the prestigious committees of Constitutional Affairs and Human Rights (Piscopo 2011a:265).

Anotherinstitutionalstructuresupportingwomen’s substantive representationistheChamber’sCentro de Estudios para el Adelanto de las Mujeres y la Equidad de Género (CEAMEG). This non-partisan research center, created in 2005, has two functions: (1) advising any deputy (not just CEG members) in the design of gender policies and (2) cataloging statistics related to women’s substantive representation in both chambers of the Mexican Congress. Both institutions legitimize bill introduction on women’s interests.

4. Evidence for the descriptive-substantive connection in Mexico

CEAMEG’s statistical archives present an opportunity to study the overall patterns of women’s substantive representation in Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies. CEAMEG tracks two categories of legislation: equal rights legislation across all policy areas (from employment to healthcare) and legislation that affects children. To be counted, the legislation must specifically mention the rights of women or the wellbeing of children. This approach categorizes substantive representation not by the general policy area, but by the specific invocation of women or children in the proposal. General social policy bills (meaning bills that address education or health without specifically identifying women or children as beneficiaries) are set aside.

Women’s rights and child wellbeing are both constitutive of women’s substantive representation. Women clearly have a shared interest in equalizing their legal, political, and social rights vis-à-vis men, and studies of substantive representation in Latin America typically conceptualize women’s interests as aligning with these feminist visions of women’s roles (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008; Htun and Power 2006; Htun, Lacalle, and Micozzi 2013; Schwindt-Bayer 2010). Progressive visions notwithstanding, women also have a traditionally gendered association with hearth and home. Consequently, scholars have also conceptualized women’s interests as including policies related to domestic matters and children (Schwindt-Bayer 2006; 2010). The “children’s legislation” tracked by CEAMEG includes measures that combat pedophilia, restrict child labor, and establish national coordinating offices of children’s rights.

CEAMEG does not track non-feminist legislation, that is, measures circumscribing women’s legal, political, and social freedoms and thus restricting equal rights. Yet under a values-neutral approach to women’s substantive representation, such legislation cannot be excluded. As noted, many conservative politicians do claim to speak for women (Celis and Childs 2012), even if their proposed policies –criminalizing abortion, for instance– seem antithetical to feminist understandings of women’s equal rights. Indeed, these claims typically base policies on women’s difference: for example, women’s reproductive freedoms are not the same as men’s reproductive freedoms, due to women’s biologically-determined capacity, and thus obligation, to bear children. Such claims may resonate strongly in Latin American, where female politicians have often justified their political participation by appealing to women’s naturally superior mothering roles (Chaney 1973; Craske 1999). Moreover, policies that align women’s interests with traditional gender roles remain an important comparison category: conclusions can be drawn about how much substantive representation occurs generally versus how much substantive representation is feminist specifically.

My dataset on women’s substantive representation in Mexico thus includes three categories of women’s interest bills: (1) bills coded by CEAMEG as consistent with advancing feminist or progressive visions of women’s roles, meaning proposals that equalize women’s standing in family law, promote their educational and workforce opportunities, and expand their reproductive choice; (2) bills coded by CEAMEG as supporting children’s wellbeing; and (3) bills coded by me –from a dataset of all bills introduced in the Mexican Congress– as non-feminist, meaning bills that treat women in relation to hearth and home.[10]Non-feminist proposals are different from children’s proposals: whereas children’s proposals focus on youth’s lives beyond the home, non-feminist proposals emphasize women’s rolesinside the home. Children’s bills, for instance, impose child labor restrictions or establish programs for adolescents’ volunteerism. Non-feminist bills, by contrast, reify women’s traditional roles by limiting access to contraception and abortion and/or by affirming motherhood within the nuclear family as essential for society.[11] I study bill introduction because, as argued above, the features of the Mexican Congress –growing multipartism, institutional and electoral incentives, and party discipline in roll call votes– suggest that legislators express their policy preferences through authoring bills.

The data begin in 1997: in this year, the PRI lost its legislative majority and divided government in Mexico ushered in a new era of electoral competition (Magaloni2005). Taking all three categories of women’s interest bills together, thirty-two women’s interest bills were introduced in the LVII term (1997-2000). This number increased to 46 in the LVIII term (2000-2003), to 129 in the LIX term (2003-2006), to 153 in the LX term (2006-2009), and finally to 284 in the LXI term (2009-2012) (CEAMEG 2009; CEAMEG 2012).

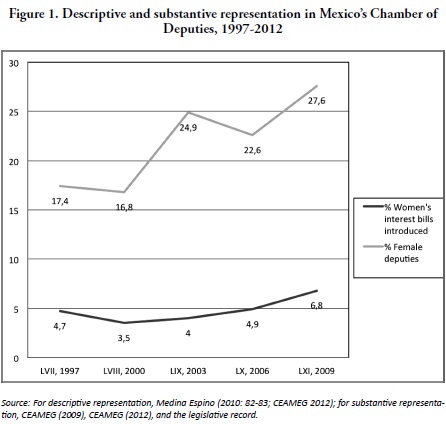

Figure 1 plots the relationship between women’s descriptive and substantive representation. For each three-year congressional term, Figure 1 shows the proportion of female legislators seated in the chamber (descriptive representation) and the proportion of women’s interest bills introduced by legislators relative to all bills introduced into the chamber(substantive representation).[12]While the absolute number of women’s interest bills has increased each congressional session, the relative proportion of these bills has remained rather flat. This occurs because Mexican deputies’ overall workloadhas increased: deputies introduced 685 bills in the LVII term (1997-2000), 1310 bills in the LVIII term (2000-2003), around 3000 bills in the LIX and LX terms (2003-2006 and 2006-2009), and 4198 bills in the LXI term (2009-2012). Thus, women’s substantive representation accounted for roughly 3.5 to 5 percent of overall bill introduction between 1997 and 2009, even as women’s descriptive representation climbed. However, in the 2009-2012 term, women’s descriptive representation reached 27.6 percent and women’s substantive representation jumped to 6.8 percent (284 of 4198 bills). The overall correlation between descriptive representation and substantive representation is a strong .688.

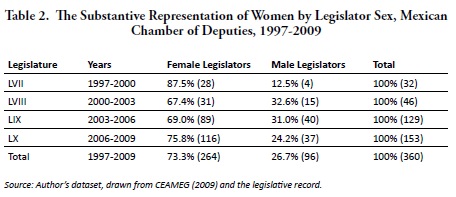

Disaggregating the bill introduction data by sex further demonstrates that female deputies author the vast majority of these women’s interest proposals. As Table 2 shows, no matter the congressional term, female deputies are largely responsible for introducing women’s interest bills: women’s efforts accounted for nearly 90 percent of women’s substantive representation in the LVII term, nearly 70 percent in the LVIII and LIX terms, and about 75 percent in the LX term.[13]Examining the 1997-2009 period as a whole reveals that female deputies authored 73.3 percent of the women’s interest bills, compared to male deputies, who authored 26.7 percent of the bills. Male deputies introduced less than one third of the women’s interest proposals each congressional term and in total.

Moreover, a greater proportion of individual female deputies undertake women’s substantive representation when compared to individual male deputies. Table 2 reports data on the 360 women’s interest bills across all three categories that were introduced by legislators between 1997 and 2009. These bills are authored by 210 individual legislators, 128 women and 82 men.[14]In other words, 61 percent of legislators undertaking women’s substantive representation are women, and 39 percent are men. However, comparing these 128 women and 82 men to the total number of women (408) and men (1592) reveals that the relative frequency with which women and men undertake substantive representation is dramatically different.[15]Thirty one percent of female deputies (128 of 408) serving between 1997 and 2009 authored at least one women’s interest bill, compared to just 5 percent (82 of 1592) of male deputies serving during the same period. Again, female legislators are more likely to represent women.

This finding also appears within the political parties. Again examining the 1997-2009 period as a whole, deputies from Mexico’s three dominant parties –the PRI, the PAN, and the PRD– introduced most of these measures. Of those authored by the formerly hegemonicPRI, 76.5 percent were authored by female priístas. Of those authored by the neoliberal, Catholic PAN, 68.1 percent were authored by female panistas. Finally, of those authored by the leftist PRD, 76.5 percent were authored by female prd-istas. Of the minor parties represented in the Mexican Congress, small leftist parties have the largest sex gap in bill authorship: female leftists introduced 83.9 percent of their parties’ women’s interest bills.[16]The Partido Verde Ecologista de México (PVEM), a small environmental party, constitutes the exception to this pattern, with female verdistas authoring a minority –43.8 percent– of their party’s women’s interest bills. The PVEM, however, is not a classically left party despite its green platform. The PVEM has opportunistically and variously allied itself with the neoliberal PAN and the corporatist PRI, and the party has endorsed rightist policies, such as state violence against drug traffickers and the death penalty (Terra 2012).

Overall, then, the data reveal a positive correlation between women’s descriptive representation and women’s substantive representation. In Mexico, as elsewhere in Latin America, women’s substantive representation –operationalized as bill introduction– is largely carried out by female legislators rather than male legislators. This trend appears for the legislature as a whole and within each political party (except for the PVEM), indicating that gender identity –as proxied by sex– does affect substantive representation.

Female legislators also perceived these patterns, with all fifteen interviewees, who represented the PAN, PRI, and PRD, observing that women in the Mexican Congress shouldered the responsibility of women’s substantive representation. While one legislator attributed this greater responsibility to the popularity of gender legislation in the chamber generally, most attributed substantive representation to the demands, expectations, and preferences associated with gender role socialization.[17] Importantly, this latter explanation was shared across party lines. For instance, a PRD legislator commented that women are “responsible for all social themes in the chamber,” including women’s rights; a longtime PRI congresswoman reflected that “woman have a more sensitive streak on questions of women, children, the elderly, and anything related to wellbeing.”[18]Similarly, a PAN legislator explained women’s social sensibility by referring to their greater familiarity with sacrifice and suffering.[19]

These comments reflect female legislators’ understanding of a gendered division of labor in the Mexican Congress. Nonetheless, male legislators do not entirely neglect women’s substantive representation, with their share of bill introduction even approaching 30 percent in two congressional terms (Table 2). One explanation may be that female legislators have socialized their male colleagues into representing women, but do not acknowledge men’s contributions. All women’s interest bills are forwarded to the CEG, which is perceived as an exclusively female domain. Female legislators like to joke about the only male member since its creation: he arrived at the first meeting, fled, and never came back.[20]Another explanation might relate to the proposals’ content: perhaps male legislators must advocate specific objectives in order for their female peers to recognize them as substantively representing women. The measure of women’s substantive representation used here includes bills with feminist and non-feminist visions of women’s roles, as well as bills focused on children. This measure may collapse important variations in female legislators’ and male legislators’ approach to women’s interests.

5. The content of women’s substantive representation

The dataset’s three constituent categories –feminist/progressive roles, non-feminist/traditional roles, and children– provide further insight into how legislators substantively represent women. Disaggregating the measure of women’s substantive representation reveals that the vast majority of women’s interest bills advance progressive visions of women’s roles. This evidence suggests that most legislators adopt feminist perspectives, and that female deputies are more feminist when compared to male deputies. Thus, male legislators substantively represent women, but less frequently from a standpoint associated with expanding their rights and roles.

5.1. Sex and party differences

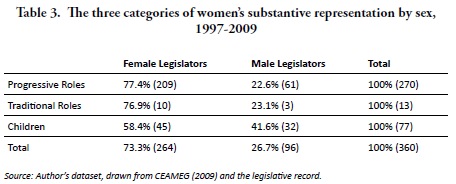

Straightforward cross-tabulations for the 1997-2009 period show the predominance of efforts to promote women’s equal rights. Seventy-five percent (270) of all measures (360) fall into this category, which includes the following proposals: reforms to Mexico’s civil code to equalize women’s standing in marriage, inheritance, divorce and child custody; modifications to labor laws that allow women to succeed in the workforce (i.e., improving pay equity and expanding maternity leave); measures to expand access to contraception and abortion; efforts to combat sexual violence and sex trafficking; expansions of social assistance to impoverished or widowed women; and generalized women’s rights measures. Only a small minority of women’s interests bills –3.6 percent (13)– aim to reify women’s traditional roles by curbing reproductive choice or supporting the nuclear family (i.e., providing subsidies for stay-at-home mothers). About one-fifth –21.4 percent (77)– focus on children’s wellbeing; that is, children –not nuclear families or women– are the objects of the legislation. For example, these measuresenforce child labor restrictions or punish pedophilia.[21]

Table 3 disaggregates the data by category and by sex. The results are consistent with the overall trend reported in Table 2: female deputies author the vast majority of bills in each of the three women’s interest categories, and the sex difference is statistically significant at the 1 percent level.[22]Female deputies introduced 77.4 percent of all bills that envision progressive roles, and they introduced 76.9 percent of the few bills that reinforce traditional gender roles. Notably, female legislators wrote relatively fewer bills on children –58.4 percent– when compared to progressive gender roles and traditional gender roles. Male deputies, by contrast, introduced less than one-quarter of the bills addressing women (whether from a feminist or non-feminist perspective), but over two-fifths of the bills addressing children.

Interviewee comments underscore these trends. As described above, female legislators explained women’s greater responsibility for substantive representation by broadly connecting women’s gender identity to social issues. Yet when asked to name specific policies that substantively represent women, no interviewees mentioned proposals benefiting children. Instead, interviewees, including panistas, exclusively referenced feminist proposals: they cited their work on sexual violence, women’s political representation, job protection during maternity leave, the creation of the state women’s agency (InMujeres), the gender analysis of the federal budget spearheaded by CEAMEG, and the special legislative commission to address the femicides in Ciudad Juarez.

These findings signal an important methodological point about grouping children and women together into one “women’s interest” category. If the measure is not disaggregated, differences between female legislators’ and male legislators’ substantive representation may not be accurately captured. Female legislators focus their attention on women’s rights and roles, specifically progressive rights and roles, while male legislators emphasize children’s wellbeing over women’s rights and roles.

How this finding may reshape the traditional conceptualization of children as a women’s interest is revisited in the conclusion. For now, the difference between women’s bills and children’s bills also appears when women’s substantive representation is disaggregated by party. Feminist proposals constituted the majority of all parties’ women’s interest bills. However, while progressive initiatives accounted for 80.7 percent and 83.3 percent of priístas’ and prd-istas’ substantive representation, respectively, such proposals only accounted for 52.8 percent of panistas’ efforts. When panistas undertake women’s substantive representation, they, like male deputies, pay significant attention to children’s wellbeing.

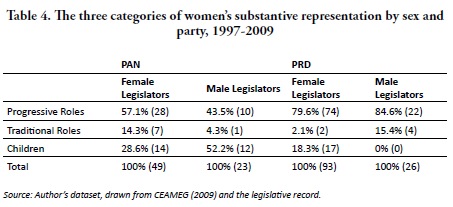

This result can be further explored by comparing women’s substantive representation in the rightist PAN to the leftist PRD. As noted, the majority of both parties’ proposals addressed progressive gender roles. However, as shown in Table 4, this trend is much stronger in the PRD. When undertaking women’s substantive representation, women and men in the PRD write proposals on progressive gender roles 79.6 percent and 84.6 percent of the time, respectively, compared to women and men in the PAN, who write proposals on progressive gender roles 57.1 percent and 43.5 percent of the time, respectively. The PAN particularly illustrates how male deputies’ substantive representation of women can be masked by policy preferences that actually center on children. Of those male panistaswho write women’s interest bills, the majority focus on children (52.2 percent). By contrast, the overwhelming majority of male prd-istaswriting women’s interest bills emphasize progressive gender roles (84.6 percent).

These findings suggest that party ideology interacts with sex to shape patterns of women’s substantive representation in Mexico. The overall trend among Mexican legislators generally, and among legislators in the PAN, PRI, and PRD specifically, is to equalize women’s economic, political, and social status. This trend is stronger for women compared to men, and for leftists compared to non-leftists. Rightist legislators in general, and male rightists in particular, embrace progressive roles less enthusiastically, and child welfare more enthusiastically, when compared to their leftist counterparts.

5.2. The predictive power of sex and party

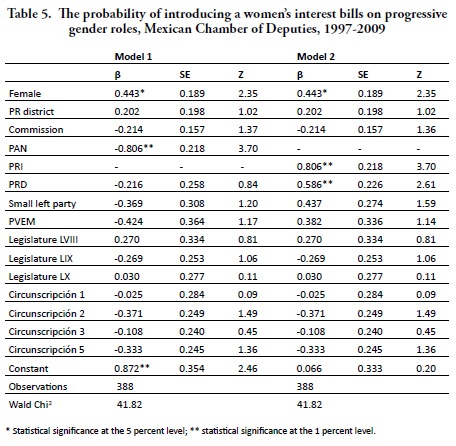

Yet which independent variable –legislators’ sex or legislators’ party ideology– can better predict their policy preferences on women’s rights? A statistical model can isolate these effects. I conducted a probability (probit) regression using the women’s interest bill as the unit of analysis, in order to assess the likelihood that a bill addressing progressive gender roles would be introduced when compared to a bill addressing traditional gender roles or children. Since the research question asks whether sex or party predicts the legislator’s approach to substantive representation, the data focuses just on the women’s interest bills and just on the 210 legislators –128 women and 82 men– who wrote them. The model reveals which deputy characteristics predict a feminist approach to women’s substantive representation, not which deputy characteristics predict undertaking substantive representation in the first place.

The model is constructed with the bill as the unit of analysis. Though co-authorship is uncommon (only 25 bills had coauthors), I counted proposals with coauthors once for each author. For example, if the proposal was co-authored by a PRI and a PAN deputy, the bill was counted twice: the first observation uses data from the PRI deputy, and the second observation uses data from the PAN deputy. The chief independent variable is the sex of the author, coded as female=1, male=0. Party membership enters as a series of dummy variables for each party (the PAN, PRI, PRD, PVEM or a small left party), where membership=1 and non-membership=0.

Other independent variables capture additional factors influencing Mexican legislators’ policy preferences. I control for electoral incentives with a dummy variable that captures whether the legislator was elected from a single member district (0) or a PR district (1). Since legislators’ committee membership may shape preferences or reflect legislators’ expertise, I control for whether the legislator occupies the commission which received the bill (yes=1; no=0). Finally, I include dummy variables to control for each congressional term and for deputies’ electoral districts. The latter control captures whether deputies’ SMD or PR district either fell inside (1) or outside (0) a particularcircunscripción.

Table 5 reports the regression results for two models, in which the first uses the PRI as the reference category for party and the second uses the PAN. The earliest congress in the dataset, LVII (1997-200) is the reference category for term. The reference category for is the 4thcircunscripción, which contains the global, urban metropolis of Mexico City (deputies elected from this region may be more progressive compared to legislators from elsewhere).[23]The models use robust standard errors clustered on the legislators.

The models show that legislators’ gender identity, as proxied by sex, matters: being female raises the likelihood that the deputy will introduce a proposal on progressive gender roles relative to traditional gender roles or children. Party membership also matters. Model 1 shows that, relative to the ideologically-heterogeneous PRI, members of the PAN are statistically less likely to introduce bills on progressive gender roles. Conversely, in Model 2, priístas and prd-istas are statistically more likely to advance progressive gender roles when compared to panistas. Generating predicted probabilities from the model offers more perspective: relative to the PAN, members of the PRI and PRD are 22 and 17 percent more likely to focus on progressive gender roles relative to traditional gender roles or children, respectively, whereas members of the PAN are 28 percent less likely to do so relative to the PRI and PRD.

Alternative constructions of the dependent variable also underscore the effect of membership in the PAN. When the dependent variable excludes children’s bills and compares only progressive women’s interest bills (1) to traditional women’s interest bills (0), the only statistically significant independent variable is PAN membership. Being a panista reduces the likelihood of authoring a feminist bill. Legislators’ sex is not statistically significant, though the sign is positive. When the dependent variable excludes non-feminist bills and compares children’s bills (1) to progressive women’s interest bills (0), legislators’ sex and PAN membership are significant. Being female reduces the likelihood of authoring a children’s bill, and being a panista raises the likelihood of doing so.

Across all models, institutional incentives, committee assignment, specific congressional terms, and electoral districts did not affect whether Mexican deputies represented women in feminist terms. Further, the influences of sex and party identification are independent. Terms interacting sex and party, when introduced into the models, were not statistically significant. However, the small sample size may affect this result: the party trends presented in Table 4 suggest some key difference between female panistasand female prd-ístas, and between male panistasand male prd-ístas. However, more observations might be needed to capture these interaction effects in multivariate models.

Nonetheless, these findings are consistent with those reported by Htun and Powers (2006) in their study of Brazilian legislators: both party membership and gender identity predict legislators’ positive support for women’s rights. Whereas Htun and Powers conclude, however, that leftist legislators are more likely to bring about progressive policy change than female legislators, this analysis indicates that progressive policy change requires both women and leftists. Female legislators are more likely to author feminist bills relative to non-feminist bills and children’s bills. Further, while the models show that PAN legislators are overall less likely to introduce bills that advance women’s rights, the cross-tabulations show significant support among femalepanistasfor these objectives. As shown in Table 4, individual female panistasdisplayed greater attention to progressive gender roles when compared to individual male panistas, and they introduced a larger absolute number of feminist bills than male prd-istas. Female panistasmay not undertake the bulk of feminist substantive representation, but they are certainly allies.

Indeed, interviewees stressed the importance of multi-party coalitions on progressive gender issues. A multiple term PRD congresswoman reported that “the women meet and talk and come together to support legislation with a gender perspective” and her co-partisan concurred that “there is gender solidarity among women, even among women of the PAN and the PRD, on all gender policies.”[24]Panista women agreed. A former PAN deputy commented that “there are gender issues that are obvious, that cannot be ignored, and many female deputies support them” and a PAN senator emphasized that feminist proposals –such as those related to quotas, sexual violence, and the gender analysis of the federal budget– were signed by women of all the parties.[25] A former PRI deputy discussed how legislators’ sex would often trump party allegiances: in the moment of voting on a women’s rights proposal, female deputies “would go to their party leaders and ask for permission ‘to go with the women’ and not with the party.”[26] Another priísta commented, “We are all united in our gender, and this will transcend all other political divisions.”[27] Thus, support for feminist proposals in the Mexican Congress attracts women from all parties, though the degree of enthusiasm may be tempered by party membership.

6. Conclusion

The quantitative and qualitative data from the Mexican case provide substantial support for the claim advanced by Argentine activists, “With many women in politics, politics changes” (Marx, Borner, and Caminotti 2007:61). In Mexico, female legislators introduce the vast majority of women’s interest bills, supporting the link between women’s descriptive representation and women’s substantive representation. Further, these women’s interest bills overwhelminglypromote feminist, progressive visions of women’s rights and roles. These patterns hold across political parties of differing ideologies: even women from the PAN author feminist proposals and support cross-partisan networks dedicated to gender equality. Consequently, while leftist legislators may be the most consistent advocates of women’s substantive representation, they canexpect to find allies among rightist women.

Yet the analysis presented here focuses on substantive representation as process, that is, agenda setting operationalized as bill introduction. Women in the Mexican Congress –like their counterparts elsewhere in Latin America (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008; Schwindt-Bayer 2010)– occupy seats in male-dominated legislative chambers. Female interviewees reported various forms of sexist treatment that excluded them from key decision-making posts and meetings, a marginalization that could ultimately circumscribe the success of theirproposals.[28] Of the 360 women’s interest bills analyzed here, 22 ultimately succeeded, all from the two categories of progressive gender roles and children. Specifically, these measures improved Mexico’s legal frameworks for gender equality (i.e., by expanding the legislative quota and by creating InMujeres) or enhanced penalties for pedophiles and child pornographers. How and why some women’s interest measures succeed relative to others merits additional research.

This analysis also addresses some outstanding theoretical and methodological issues surrounding the operationalization of women’s interests. A common approach has measured women’s substantive representation by including proposals on children, because women’s longstanding connection with hearth and home makes children a women’s interest. However, this measurement may be fraught: these proposals focus on children, not women, as objects of legislation. Indeed, when I analyze women’s and children’s bills separately, I find thatmany children’s billsare actually authored by male legislators. This finding may explain why, when women’s substantive representation is constructed as an aggregate measure, male legislators appear relatively active. It may also indicate why female legislators may not identify their male colleagues as women’s interest advocates: while my theoretical formulation of substantive representation is value-neutral, female deputies’ practical understanding may privilege feminist objectives advanced by women legislators.

This outcome opens several directions for future research. One avenue would examine the effect of female legislators on male legislators: do congresswomen socialize or pressure congressmen into undertaking women’s substantive representation, and, if so, what vision of women’s rights and roles do congressmen adopt? A second avenue would refine existing conceptualizations of “women’s interests” and “gender interests.” Scholars should explore whether legislators authoring proposals on children see this focus as representing women. For male legislators, representing women may evoke children’s wellbeing and not women’s rights, or protecting children may have no relationship at all to representing women. These possibilities suggest that scholars should also explore how men understand women’s interests, asking whether male legislators have interests based on their gender identities. Ultimately, scholars should consider excluding “children” from measures of women’s interests, and future work should examine not the substantive representation of women, but the gendered dimensions of policy preferences and advocacy.

Bibliography

Casar, María Amparo (2011). “Representation and decision making in theMexicanCongress”, Documento de Trabajo Número 258. Mexico City: CIDE.

Baldez, Lisa (2008). “Primaries v. quotas: Gender and candidate nominations in Mexico, 2003”.Latin American Politics and Society49(3): 69-96.

Bruhn, Kathleen (2003). “Whores and lesbians: Political activism, party strategies and gender quotas in Mexico”.Electoral Studies, Volume 22, Number 1, pp 101-119.

Caroll, Susan J (2001). The Impact of Women in Public Office.Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Chaney, Elsa (1973). “Women in Latin American politics: The case of Peru and Chile”, in Ann Pescatello (ed.) Female and Male in Latin America.Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

CEAMEG (2012). “Información Analítica 2012”. Mexico City: CEAMEG. (http://archivos.diputados.gob.mx/Centros_Estudio/ceameg/ias/IAs_2011.swf)

CEAMEG (2009). “Seguimiento de iniciativas en material de equidad de género y derechos humanos de las mujeres” Mexico City: CEAMEG (http://archivos.diputados.gob.mx/Centros_Estudio/ceameg/Seguimiento_iniciativas/StartBD.html).

Celis, Karen and Sarah Childs (2012). “The substantive representation of women: What to do with conservative claims?” Political Studies60(1): 213-225.

Craske, Nikki (1999). Women & Politics in Latin America.London: Routledge.

Díaz-Cayeros, Alberto (2005). “Endogenous institutional change in the Mexican Senate”.Comparative Political Studies38(10): 1196-1218.

Díaz-Rebolledo, Jerónimo (2005). “Los determinantes de la indisciplina partidaria”.Politica y Gobierno12(2): 313-303.

Franceschet, Susan and Jennifer M. Piscopo (2008).“Quotas and women’s substantive representation: Lessons from Argentina”.Politics & Gender4(3): 393-425.

González Tule, Luis Antonio (2007). “Cohesión partidista en la Cámara de Diputados en México”.Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas6(2): 177-198.

Hinojosa, Magda (2012). Selecting Women, Electing Women: Political Representation and CandidateSelection in Latin America.Phildelphia: Temple University Press.

Htun, Mala, Marina Lacalle and Juan Pablo Micozzi (2013). “Does women’s presence change legislative behavior? Evidence from Argentina, 1983-2007”.Journal of Politics in Latin America5(1): 95-125.

Htun, Mala and S. Laurel Weldon (2010).“When do governments promote women’s rights?” Perspectives on Politics8(1): 207–216.

Htun, Mala and Timothy J. Power (2006). “Gender, parties and support for equal rights in the Brazilian Congress”.Latin American Politics and Society48(4): 83-104.

Jones, Mark P., Sebastian Saiegh, Pablo T. Spiller and Mariano Tommasi (2000). “Amateur-legislators–professional politicians: The consequences of party-centered electoral systems”.American Journal of Political Science 46(3): 656-669.

Kerevel, Yann (2009). “The legislative consequences of Mexico’s mixed-member electoral system, 2000-2009”.Electoral Studies 29(4): 691-703.

Langston, Joy (2010). “Governors and ‘their’ deputies: New legislative principals in Mexico”.Legislative Studies Quarterly35(2): 235-258.

Langston, Joy and Francisco Javier Aparicio (2011). “Gender quotas are not enough: How background experience and campaigning affect electoral outcomes”, Documentos de TrabajoNúmero 234. Mexico City: CIDE.

Langston, Joy and Javier Aparicio (2009). “Committee leadership selection without seniority: The Mexican case”, Documentos de TrabajoNúmero 217. Mexico City: CIDE.

Magaloni, Beatriz (2005). “The demise of Mexico’s one-party dominant regime”.In Frances Hagopian and Scott P. Mainwaring (eds.)The Third Wave of Democratization in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 121-148.

Marx, Jutta, JuttaBorner and Mariana Caminotti (2007).Las legisladoras: Cupos de género y política en Argentina y Brasil.Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

Medina Espino, Adriana (2010). La participación política de las mujeres. De las cuotas de género a la paridad. Mexico City: CEAMEG.

Miguel, Luis Felipe (2012). “Policy priorities and women’s double bind in Brazil”.In Susan Franceschet, Mona Lena Krook and Jennifer M. Piscopo (eds.)The Impact of Gender Quotas, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 103-118.

Nacif, Benito (2002). “Para comprender la disciplina de partido en la Cámara de Diputados de México”.Foro Internacional40(1): 5-38.

Nava Polina, María del Carmen and Jorge Yáñez López (2003). “The effects of pluralism on legislative activity: the Mexican Chamber of Deputies, 1917-2000”. Paperpresented at the International Research Workshop, Saint Louis, Missouri, May 28-June 1.

Piscopo, Jennifer M (2011a). “Do women represent women? Gender and policy in Argentina and Mexico”, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, San Diego.

Piscopo, Jennifer M (2011b). “Gender quotas and equity promotion in Mexico”.In Adriana Crocker (ed.) Diffusion of Gender Quotas in Latin America and Beyond.New York: Peter Lang, pp. 36-52.

Schwindt-Bayer (2006).“Still supermadres? gender and policy priorities of Latin American legislators”.American Journal of Political Science50(3): 570-585.

Schwindt-Bayer (2010).Political Power and Women’s Representation in Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stevenson, Linda S (1999). “Gender politics in the Mexican democratization process. Electing women and legislating sex crimes and affirmative action, 1988-97”.In Jorge I. Domínguez and Alejandro Poiré (eds.)Towards Mexico’s Democratization: Parties, Campaigns, Elections and Public Opinion.London: Routledge, pp. 57-87.

Tarrés, María Luisa (2006). “The political participation of women in contemporary Mexico, 1980-2000”.In Laura Randall (ed.)Changing Structure of Mexico: Political, Social, and Economic Prospects.New York: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 406-423.

Terra (2013).“Partido Verde Europea critica al PVEM por ideología política”, 17 de Julio. (http://noticias.terra.com.mx/mexico/politica/partido-verde-europeo-critica-al-pvem-por-ideologia-politica,4ec5335163698310VgnVCM20000099cceb0aRCRD.html)

Ugues, Antonio, Jr., Medina Vidal, D. Xavier and Shaun Bowler (2012). “Experience counts: Mixed member elections and Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies”.The Journal of Legislative Studies18(1): 98-112.

Weldon, Jeffrey A (2004). “The prohibition on consecutive reelection in the Mexican Congress”.Election Law Journal 3(5): 574-579.

* Artículo recibido el 27 de setiembre de 2013 y aceptado para su publicación el 20 de junio de 2014

** PhD in Political Science; Assistant Professor of Politics, Department of Politics, Occidental College, Los Angeles; piscopo@oxy.edu.

[1]Interview with former PAN legislator, December 7, 2009.

[2] All interviews took place in person, in Mexico City.

[3] Constitutional reforms in December 2012 implemented reelection beginning with lawmakers seated in the 2018-2012 congress.

[4]Interview with former Priísta, December 8, 2009.

[5] The researchers cautionthat this relationship is weaker than expected given no reelection (Ugues, Medina Vidal, and Bowler 2012).

[6] Interviews with former PAN deputy, December 7, 2009; PAN senator, December 8, 2009; PRI leader, December 16, 2009. Of the fifteen women interviewed, only three had no connection with women’s organization prior to taking office.

[7]Interview with PRD deputy, December 15, 2009.

[8]Interview with PRD leader, December 16, 009.

[9]Interviews with PAN legislator, December 7 2009; PRI leader, December 15, 2009.

[10] I checked CEAMEG’s counts by performing a keyword search of all bills introduced between 1997 and 2009. I used search terms in Spanish for women, girls, children, female, or feminine.

[11] To construct this category, I performed additional keyword searches on all bills introduced in each congressional term. I used the following search terms: abortion, contraception, reproductive rights, family planning, nuclear family, family, motherhood, and maternalism. If the title of the bill was vague, I read the bill. If the bill proposed to restrict reproductive choice or presented a social policy that would protect women’s mothering roles or nuclear family units, the bill entered the dataset as a non-feminist bill.

[12] This figure includes bills sent by the executive and by the senate, thus capturing the portion of the chamber’s total workload constituted by substantive representation. However, bills sent by the executive and the senate account for a small fraction (less than 5 percent) of all bills introduced each term, meaning deputies introduce the vast majority of bills considered.

[13] Data from the LXI (2009-2012) congressional term is not disaggregated by sex and is excluded.

[14] Coauthors are counted as individual authors, so a bill with an author and a coauthor is counted as having two individual authors. Seven percent (25 of 360) of the bills had coauthors.

[15] The absence of reelection means that each congressional term seats 500 new deputies. The percentages in Table 1 can be used to calculate the number of women relative to the number of men, yielding a total of 408 women and 1592 men across the four terms.

[16]Thesmallleftparties are Alternativa, Convergencia, Nueva Alianza, thePartido del Trabajo (PT), thePartido de la Sociedad Nacionalista (PSN), and thePartido Alianza Social (PAS). These parties introduced 31 of the 360 women’s interest bills.

[17]Interview with former PRD legislator, December 8, 2009.

[18]Interviews with PRD legislator, December 3, 2009;PRI leader, December 15, 2009.

[19] Interview with PAN senator, December 8, 2009.

[20]Interview with PRD leader, December 16, 2009.

[21] Of course, most children experience sexual abuse within the home. The key distinction for coding purposes is that children—not families or women—are seen as the objects of protection.

[22] Chi2 = 11.1093, Pr = 0.004

[23] I also used an alternate coding that divided Mexico’s 32 states into north, center, and south. Neither control for district type was significant.

[24]Interviews with PRD legislator, December 15, 2009; former PRD legislator, December 9, 2009.

[25] Interviews with former PAN legislator, December 7, 2009; PAN senator, December 8, 2009.

[26]Interview with former PRI legislator, December 2, 2009.

[27]Interview with PRI legislator, December 3, 2009.

[28]Interviews with former PRI legislator, December 2 2009; PRD legislator, December 3, 2009; PRD and PAN legislators, December 8, 2009; PRI leader on December 15, 2009.