Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2023 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3053

Original Articles

Adaptation and validity evidence of LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale in Brazil

1 Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brasil, profapricilazarife@gmail.com

2 Santo Caos Consultoria em Publicidade, Brasil

This research aimed to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale (LGBT-MEWS) for the Brazilian context. The sample consisted of 226 professionals who identified themselves as LGBT, with a mean age of 28.5 years (SD = 7.19) who answered the LGBT-MEWS and a sociodemographic questionnaire. The LGBT-MEWS adaptation process followed the stages of translation, synthesis, evaluation by expert judges, evaluation by the target population, and back translation. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to assess the plausibility of the three-dimensional structure (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions, and cisnormative culture). The Brazilian version presented adequate CVI, according to expert judges. The proposed three-dimensional structure presented an excellent fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031), and good reliability indices (Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability ≥ .84). The adapted version of the LGBT-MEWS presented satisfactory quality, making it the first instrument in the Brazilian context to investigate experiences of LGBT microaggressions at work.

Keywords: discrimination at work; microaggressions; diversity in organizations; sexual and gender minorities; validity.

Esta pesquisa buscou adaptar e obter evidências de validade de estrutura interna da Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho (EEM-LGBT) para o contexto brasileiro. Participaram 226 profissionais que se identificaram como LGBT, com idade média de 28,5 anos (DP = 7,19) que responderam à EEM-LGBT e um questionário sociodemográfico. O processo de adaptação da EEM-LGBT seguiu as etapas de tradução, síntese, avaliação por experts, avaliação pelo público-alvo e tradução reversa. Para avaliar a plausibilidade da estrutura tridimensional (valores no local de trabalho, suposições heteronormativas e cultura cisnormativa) foi realizada análise fatorial confirmatória. A versão em português apresentou IVC adequado, segundo juízes experts. A estrutura tridimensional proposta apresentou um ótimo ajuste aos dados (χ2/gl = 1,22; CFI = 0,994; TLI = 0,993; SRMR = 0,076; RMSEA = 0,031) e bons índices de confiabilidade (alfa de Cronbach e confiabilidade composta ≥ 0,84). A versão adaptada da EEM-LGBT apresentou qualidade satisfatória, tornando-se o primeiro instrumento no contexto brasileiro destinado a investigar experiências de microagressões LGBT no trabalho.

Palavras-chave: discriminação no trabalho; microagressões; diversidade nas organizações; minorias sexuais e de gênero; validade.

Esta investigación buscó adaptar y obtener evidencias de validez de la estructura interna de la Escala de Experiencias de Microagresiones LGBT en el Trabajo (EEM-LGBT) para el contexto brasileño. Participaron 226 profesionales que se identificaron como LGBT, con una edad media de 28.5 años (DE = 7.19), que respondieron el EEM-LGBT y un cuestionario sociodemográfico. El proceso de adaptación de EEM-LGBT siguió las etapas de traducción, síntesis, evaluación de expertos, evaluación de la audiencia objetivo y retrotraducción. Para evaluar la plausibilidad de la estructura tridimensional, se realizó un análisis factorial confirmatorio. La versión portuguesa presentó CVI adecuado, según los jueces expertos. La estructura tridimensional propuesta presentó un excelente ajuste a los datos (χ2/gl = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031) y buenos índices de confiabilidad (alfa de Cronbach y confiabilidad compuesta ≥ .84). La versión adaptada del EEM-LGBT fue de calidad satisfactoria, lo que lo convierte en el primer instrumento en el contexto brasileño para investigar experiencias de microagresiones LGBT en el trabajo.

Palabras clave: discriminación en el trabajo; microagresiones; diversidad en las organizaciones; minorías sexuales y de género; validez.

In many parts of the world, identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or transvestite (LGBT) can result in a loss of rights, violence, and even the risk of death (Redcay et al., 2019). Such intolerance can occur in different spheres, such as organizations, family, religious, educational, and health institutions (Salgado et al., 2017). In Brazil, the country with the highest rate of lethal crimes against LGBT people (Mendes & Silva, 2020), the Federal Supreme Court (2019) established homophobia and transphobia as crimes equivalent to acts of racism.

Even in contexts with protective legislation, LGBT people continue to be stigmatized, especially in countries with conservative cultures (Redcay et al., 2019). In addition, violence considered to be silent or subtle has become increasingly frequent, as it is not reported or considered under the terms of the law (Souza et al., 2017). Among subtle violence are microaggressions, defined as verbal, behavioral, or environmental abjections that convey contempt and insults and are directed at minority groups, such as LGBT people (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). Even if subtle and brief, they negatively impact their victims, causing low self-esteem, depression, trauma (Nadal, 2019), sadness, withdrawal from regular activities, and suicidal ideation or attempts (Parr & Howe, 2019).

Subtle discrimination against LGBT people at work is usually less noticeable than acts of physical or sexual violence (Souza et al., 2017). However, they can have an impact on their entry and permanence in the job market, combined with the neglect of basic rights and social vulnerability. Transgender people face even more difficulties, such as high rates of unemployment, underemployment, and job dissatisfaction, as well as being directed to informal jobs, self-employment, and prostitution (Costa et al., 2020).

In the face of microaggressions suffered at work, LGBT people often employ different coping strategies, such as remaining passive in the face of aggression (not reacting and ignoring negative comments, even though they are negatively affected), confronting the aggressor (reacting actively and challenging them) or emitting self-protective behaviors (acting cautiously to ensure their physical safety, such as keeping an eye on their surroundings) (Nadal et al., 2011; Papadaki et al., 2021). Regarding possible cognitive reactions to such events, they tend to accept that such aggression is part of life as an LGB person, seek to empower themselves to respond to aggressors, or come out about their sexual orientation, if they have not already done so (Papadaki et al., 2021).

The literature dealing with discrimination against LGBT people at work and its impact is still relatively incipient (Richard, 2021), even more so when it comes to measuring instruments aimed at explicitly investigating microaggressions directed at this section of the population. The few quantitative studies tend to make changes to the wording of measures that investigate racial discrimination, so that they can be applied to LGBT people (Medina, 2022). Considering that it is of the utmost importance to investigate the occurrence and impact of such experiences on LGBT people, measuring instruments specifically designed for them can be an important research strategy.

The LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale (LGBT-MEWS, Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho/EEM-LGBT) is a measurement instrument developed in the United States to investigate this type of discrimination. Different strategies were adopted in its development: literature review, reports of LGBT people who have suffered microaggressions in the workplace and analysis of instruments that investigated heterosexist experiences, involving both inductive and deductive strategies (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Initially, 64 items were developed and subjected to investigation of validity evidence based on content and internal structure, by means of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The final version consists of 27 items distributed in three dimensions with the following fit indices χ2 (321) = 1226.30; p< .001, CFI = .76; SRMR = .08; RMSEA = .09; 90 % (.091, .102) and reliability (Cronbach's alpha) between .82 and .93. Although the CFI (Comparative Fit Index) was lower than recommended, with the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residuals), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) and confidence interval below .10, the inadequacy test was rejected, indicating the use of the instrument (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

The three-dimensional model derived from the construction of the measure is composed of (1) workplace values, (2) heteronormative assumptions, and (3) cisnormative culture. The workplace values dimension is related to the general value system of an organization, involving LGBT workers' interpersonal interactions with their colleagues (such as derogatory jokes and insults), as well as their status at work related to hiring, promotion, pay scale, and job security (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). The heteronormative assumptions dimension describes everyday heterosexism at work that invalidates the experience and identity of LGBT professionals, such as the assumption that the person is heterosexual and statements to marginalize, invalidate or discredit their experiences as an LGBT person (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). It is worth noting that, traditionally, some organizations may have a more heteronormative culture than other social spaces, especially when they are predominantly made up of cis heterosexual men (Palo & Jha, 2020). The cisnormative culture dimension is related to disrespect for a person's gender identity and/or expression and how it is experienced at work, reinforcing that people identify with the sex assigned at birth, disregarding the multiplicity of gender identities and expressions. This involves the absence of inclusive policies relating to the use of toilets, neutral language, and dress code. For the model, this separation between dimensions is of paramount importance to reinforce that there are differences in the microaggressions suffered by transgender people (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

A quantitative survey of 325 American LGBT professionals using the LGBT-MEWS found that microaggressions positively predicted stress at work (( = .23; p< .001), symptoms of stress (( = .05; p< .001), depression (( = .05; p< .001) and anxiety (( = .06; p< .001), symptoms of stress (( = .05; p< .001), depression (( = .05; p< .001) and anxiety (( = .06; p< .001), as well as negatively predicting job satisfaction (( = -.17; p< .01). The results also showed that even people who do not openly identify as LGBT can also suffer discrimination (Richard, 2021).

Another quantitative study with 88 cisgender and LGB American professionals, which adopted the LGBT-MEWS, identified the variables concerns about acceptance (( = .24; p= .034) and motivation to hide sexual orientation (β = .49; p< .001) as predictors of microaggressions (F(2, 85) = 9.97; p< .001; R2 = .19). Furthermore, microaggressions did not significantly predict satisfaction with the romantic relationship (Medina, 2022). Finally, another quantitative survey, conducted with 314 LGBT professionals living in Canada (66 %) and the United States (34 %) and adopting the LGBT-MEWS, identified a high correlation between incivility (rude and disrespectful behavior) and microaggressions (r = .64; p< .001). The results indicated that the relationship between microaggressions and work engagement (b = -.10; p< .05) was considered significant only when combined with outness (the degree to which a person reveals their sexual orientation and/or gender identity) as a potential moderating variable (Sooknanan, 2023).

Although LGBT people are one of the most marginalized groups in Brazilian organizations, there is a lack of research on their experiences in the workplace (Zanin, 2019). As for microaggressions against LGBT people at work, there is no measuring instrument to investigate their occurrence in Brazil, making it difficult to identify their occurrence, their impacts, and the development of strategies to prevent them. Given these gaps, with the aim of fostering new studies and helping organizations manage diversity, this research sought to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the LGBT-MEWS for the Brazilian context.

The choice to adapt an international instrument was based on the advantages of this procedure compared to developing a new measure. These include the possibility of comparing data collected with the same measure in samples from different contexts and populations, making the assessment more equivalent, and greater ability to generalize the results (Borsa et al., 2012).

Method

This section is divided into two parts. The first corresponds to the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the instrument for the Brazilian context. The second corresponds to the process of finding validity evidence of the internal structure.

Part 1: Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the scale

The authors of the original version of the LGBT-MEWS were consulted and authorized the research. The adaptation followed the following steps: translation of the instrument into the new language, synthesis of the translated versions, evaluation by experts judges, evaluation by the target population, and back translation (Bandeira & Hutz, 2020; Borsa et al., 2012).

The instrument was translated from English into Brazilian Portuguese by three people who were native speakers of Portuguese and fluent in English, studying Psychology and belonging to the research's target population (two cisgender gay men and one cisgender lesbian woman), who were intentionally selected by the research team based on the aforementioned characteristics, and contacted by e-mail. The team then analyzed the three translated versions to obtain a single version, evaluating the semantic, linguistic, contextual, and conceptual discrepancies.

A committee of expert judges individually evaluated the equivalence between the translated version and the original instrument in terms of semantic, idiomatic, experimental, and conceptual equivalence. The committee was made up of four researchers in the field of Psychology (three professors with a doctorate and one with a master's degree), experienced in the construction and adaptation of instruments, two of whom were part of the target population of the research, whose selection was also intentional, and contact was made by e-mail. The notes were analyzed by the research team, considering the conceptual equivalence with the original version and the proportion of agreement between the judges, calculated by the Content Validity Index (CVI). The interpretation considered a CVI above .80 to be desirable (Alexandre & Coluci, 2011).

Next, four people from the target population evaluated their understanding of the version from the previous stage: a cisgender gay man with a postgraduate degree in Marketing, a cisgender bisexual man with a degree in Mechanical Engineering, a cisgender lesbian woman with a degree in Veterinary Medicine and a heterosexual transgender woman with completed high school, who were sampled by snowball and contacted by e-mail. They were interviewed individually, reading aloud each topic of the instrument and explaining their understanding of it. When they reported problems understanding, they were asked to suggest synonyms and semantic changes. In the end, the suggestions were evaluated by the research team based on clarity, equivalence to the original version, and frequency of suggested changes.

Finally, the instrument was translated from Portuguese into English by a professional translator who is a native speaker of Brazilian Portuguese and has a degree in Psychology. The back-translated version was analyzed by the research team and sent to the authors of the original instrument to identify inconsistencies and conceptual errors between the versions.

Part 2: Investigation of the validity evidence of the internal structure and reliability of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context

Participants

The sample consisted of 226 LGBT professionals, aged between 18 and 56 (M= 28.50; SD= 7.13), 57.40 % of whom were male (n= 128), 38.56 % female (n= 86) and 4.04 % non-binary (n = 9). Transgender or transvestite people made up 11.95 % (n= 27) of the sample, 6.64 % (n= 15) of whom said they had a social name.

The participants identified themselves as gay (51.35 %; n= 114), bisexual (22.98 %; n= 51), lesbian (20.72 %; n= 46), heterosexual (transgender) (3.15 %; n= 7), asexual (1.35 %; n= 3), and pansexual (.45 %; n= 1). The majority declared themselves to be white (61.50 %; n= 139), followed by brown (25.22 %; n= 57), black (10.62 %; n = 24), yellow (2.22 %; n = 5) and indigenous (.44 %; n= 1). The majority lived in the southeast (80.97 %; n= 183), followed by the south (7.08 %; n= 16), northeast (5.31 %; n= 12), midwest (4.43 %; n= 10) and north (2.21 %; n= 5), predominantly in inland cities (53.78 %; n= 121).

The majority were single (69.91 %; n= 158), living with a partner, married or in a stable union (28.32 %; n= 64), and separated or divorced or widowed (1.77 %; n= 4). There was a predominance of people with complete higher education (30.63 %; n = 68), followed by incomplete higher education (27.03 %; n= 60), complete postgraduate degrees (23.87 %; n= 53), incomplete postgraduate degrees (11.26 %; n= 25), complete secondary education (5.86 %; n= 13), incomplete secondary education (.90 %; n= 2), and incomplete primary education (.45 %; n= 1). As for the length of time they had worked for the company, they had been working for between 4 months and 32 years (M= 3.16; SD= 4.99).

Instrument

Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho (EEM-LGBT, LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale/LGBT-MEWS; Resnick & Galupo, 2019). The instrument consists of 27 items, divided into three dimensions: workplace values (12 items), heteronormative assumptions (9 items), and cisnormative culture (6 items). The answers were marked on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

Socio-demographic data questionnaire. Questions about age, region of the country, city, skin color, marital status, schooling, length of time in the company, gender identity, social name, and sexual orientation.

Ethical and data collection procedures

The research was carried out in compliance with the requirements of Resolution 510/2016 of the National Health Council (CNS), which deals with research involving human beings. Data collection began after approval by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Uberlândia (CAEE: 39232120.2.0000.5152).

The inclusion criteria involved identifying as an LGBT person, being of legal age, and having at least three months of professional experience. People without access to the internet and who declared themselves illiterate or with some impairment that prevented them from understanding the instrument were not included.

The instrument was made available online via a virtual link (Google Forms) which gave access to an online form containing the Informed Consent Form (ICF), with the general objective of the research, confidentiality of data and conditions for participation, and the survey questionnaire. The link was shared on social media (Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn) and sent to groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) aimed at LGBT people, using the snowball method. Data collection took place between June and August 2021.

On opening the link, the participant had access to the online version of the ICF. After reading the document, they had to sign the mandatory "I have read, understood, and am interested in participating in the research" option in order to access the questionnaire. If they did not agree to take part, they would receive a thank you message, ending their participation.

Data analysis procedures

The data collected was tabulated and analyzed using JASP software, version 0.16. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the plausibility of the three-dimensional structure. The Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (RDWLS) estimation method was adopted due to its suitability for categorical data (Li, 2016).

The fit indices and their reference values investigated were: (2 (not significant((((2/df< 3; Comparative Fit Index (CFI > .95); Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > .95); Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR < .08) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < .06, with confidence interval (upper limit) < .10) (Brown, 2015). The reliability of the measure was investigated by Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, with values above .70 being acceptable (Valentini & Damásio, 2016).

Results

Part 1: Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the scale

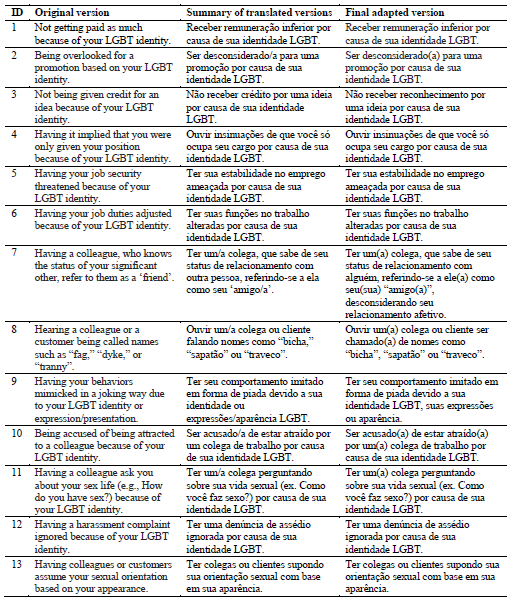

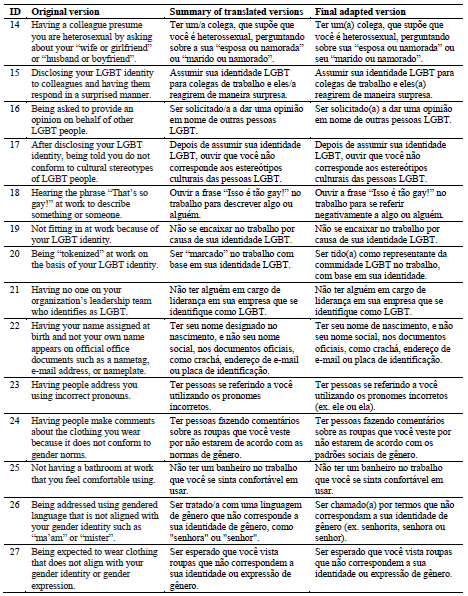

The original version of the LGBT-MEWS is shown in Table 1. In the translation from English to Portuguese, it should be noted that the translators pointed out the need to find an equivalent translation for the term tokenized in item 20 (Being “tokenized” at work on the basis of your LGBT identity), as its direct translation would be "tokenizado", an unusual word in Brazil. In the synthesis of the translated versions, we opted to use labeled to replace tokenized. In the other items, it was necessary to add gender inflections (e.g. a/o) or neutral terms (e.g. someone) in the Brazilian Portuguese version, as the original language of the instrument has a neutral language (e.g. a or an).

In the expert judges' analysis, the CVI results were adequate: instructions (1), response scale (1), workplace values dimension (.98), heteronormative assumptions dimension (.94), and cisnormative culture dimension (1). The qualitative evaluation of the judges' suggestions resulted in changes to the response scale and items 20 and 22. On the response scale, there was a change from sometimes to occasionally, making it possible to understand a moderate intensity.

In item 20 (Being “tokenized” at work on the basis of your LGBT identity), considering the original term tokenized, the judges' suggestion culminated in the modification to “Being seen as a representative of the LGBT community at work, on the basis of your identity”. In item 22 (Having your name assigned at birth, and not your social name, on official documents such as a badge, e-mail address, or nameplate), the term assigned at birth was removed and replaced with birth name. The changes were made and compiled into a single version (Table 1).

In the evaluation by the target population, items 3, 7, 9, 18, 23, 24, and 26 were changed. In item 3 (Not receiving credit for an idea because of your LGBT identity), the term credit has been changed to recognition. In item 7 (Having a colleague, who knows about your relationship status with another person, refer to them as your 'friend'), the phrase “disregarding your emotional relationship” has been included, emphasizing that it is a way of minimizing the relationship. In item 9 (Having your behavior imitated as a joke due to your LGBT identity or expressions/appearance), the ending has been changed to “LGBT identity, its expressions or appearance”, making it easier to understand. In item 18 (Hearing the phrase “That's so gay!” at work to describe something or someone), the phrase "to refer negatively to" has been included, emphasizing the negative view. In item 23 (Having people refer to you using the incorrect pronouns), examples “(e.g. he or she)” have been added to the end of the sentence, making it easier to understand. In item 24 (Having people make comments about the clothes you wear because they don't conform to gender norms), the term norms has been changed to social standards, highlighting that it deals with social issues. Item 26 (Being addressed with gendered language that doesn't correspond to your gender identity, such as “ma'am” or “sir”) has been changed to “Being called by terms that don't correspond to your gender identity (e.g. miss, ma'am or sir)”, using clearer language and adding another example. As for the gender inflections in items 2, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16, 20, and 26, bars have been replaced by brackets, improving comprehension. The target population version, corresponding to the final adapted version, is shown in Table 1.T2

This version was back-translated and sent to the authors of the original instrument. For them, the version was adequate, but there was a change in the response scale (from always to very often), since it would be less likely for someone to tick the first one, as it would indicate that the situation would happen every time. After this change, the final version was approved by the authors.

Part 2: Investigation of the Validity Evidence of the Internal Structure and Reliability of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context

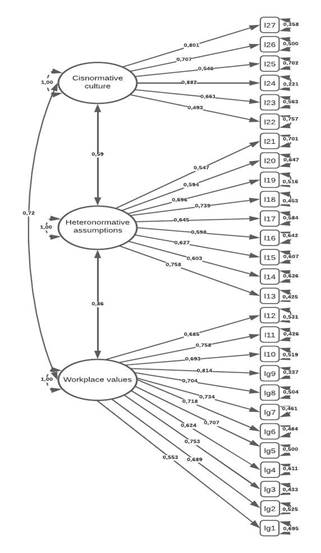

Considering the original structure of the EEM-LGBT, the first-order model with three independent dimensions (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions and cisnormative culture) was tested in this study. The results of the CFA indicated an excellent fit of the model to the data: χ2 /df = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031 (90% CI, .018 - .041), suggesting its plausibility. The results of the model structure are summarized in Figure 1.

After the CFA, reliability analyses were carried out. The results indicated adequate Cronbach's alphas: workplace values (.92), heteronormative assumptions (.86), and cisnormative culture (.86). The composite reliability was also adequate: .92, .86, and .84, respectively.

Discussion

This research sought to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context. The first part of the research, referring to adaptation to the Brazilian context, followed the six stages proposed by Borsa et al. (2012) and Bandeira and Hutz (2020). The choice of this adaptation model was because, unlike other models, it included important aspects, such as the evaluation of the instrument's items by the target population and dialog with the authors of the original instrument, verifying possible adjustments to the final version.

In the synthesis stage, an important piece of information was considered: the need to add gender inflections or neutral terms. In the Portuguese language, masculine inflection was traditionally considered a neutral/generic term, but it is exclusionary, especially when it comes to LGBT people (Covas & Bergamini, 2021). Thus, this change sought to make the instrument more inclusive.

In the judges' analysis, the CVI was used to calculate the level of agreement, with satisfactory results. This is the method most commonly used to investigate evidence of content validity, as it makes it possible to analyze the indices of each item and the instrument as a whole (Alexandre & Coluci, 2011; Kovacic, 2019). The version synthesized in this study showed semantic, idiomatic, and conceptual equivalence compared to its original version, with few changes, indicative of quality.

The analysis by the target population indicated important changes, such as the addition of examples, modifications to terms, and the adoption of parentheses in gender inflections. These changes are in line with the literature, which points out the importance of this stage to ensure that the instrument is accessible and understandable to the target population (Bandeira & Hutz, 2020; Borsa et al., 2012).

The version was translated into the original language and submitted for analysis by the authors of the instrument, culminating in a change to the response scale. This check is important to indicate possible inconsistencies and conceptual errors between the versions. It is worth noting that this stage is rarely present in other models for adapting measures, despite its importance (Borsa et al., 2012).

The second part of the research, relating to the investigation of validity evidence based on the internal structure, aimed to guarantee the applicability of the instrument in the Brazilian context. By adopting CFA, it was possible to investigate whether the underlying theory (model investigated) fitted the data obtained in the Brazilian context. Considering the first-order model with three dimensions (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions, and cisnormative culture), the results indicated an excellent fit to the data, proving superior to the preliminary results obtained in the original study. This is because, in the case of this study, all the indicators investigated showed adequate results considering the reference values adopted. On the other hand, the original study presented a CFI below that indicated, despite the RMSEA and SRMR being within the expected range, which would indicate its use (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Regarding the reliability of the Brazilian version of the EEM-LGBT, this research adopted two indicators: Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability. Cronbach's alpha is the index most commonly used to assess the reliability of instruments (Valentini & Damásio, 2016), and it was used in the original study of the EEM-LGBT and showed values within the range indicated by the literature. The results found in this study were adequate and equivalent to the results of the original study (Resnick & Galupo, 2019), indicating the robustness of the instrument in different populations.

Despite its widespread use, the literature has argued against the adoption of this indicator, as it assumes that all items have the same importance for their dimension, which is rarely the case. In view of this, there is a strong emphasis on the adoption of composite reliability, a more robust indicator that considers factor loadings as subject to variation (Valentini & Damásio, 2016). The composite reliability values presented in this study met those recommended in the literature, indicating their accuracy.

The results showed that the process of adapting and finding validity evidence of the internal structure of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context was of good quality, achieving the objectives defined in this work and indicating its adoption in other research and making it the first instrument to investigate LGBT microaggression experiences in the Brazilian context. Its use can help organizations diagnose and manage diversity. In addition, it can be used to encourage research in the area and help provide a better understanding of the phenomenon and the experience of LGBT professionals in the workplace, given the lack of publications in Brazil.

However, the study's limitations were the collection of data online and in intentional and snowball formats. The majority of respondents were white professionals with high levels of education, diverging from the general Brazilian population. In addition, around half of the participants declared themselves to be cisgender gay men. According to the literature, they represent the majority of participants in surveys with LGBT people in organizations (Silva et al., 2021). This disproportionate participation of LGBT professionals can have repercussions on diversity policies in organizations, making them predominantly focused on this group, to the detriment of other sexual orientations, identities, and gender expressions.

There was also low participation from transgender people and transvestites, a situation similar to previous research in the area (Resnick & Galupo, 2019; Richard, 2021). The job market is particularly difficult for this section of the population, which has the highest unemployment rates and tends to be directed towards informal and self-employed work (Costa et al., 2020), which may reflect in their low participation in surveys.

The topic of microaggressions in Brazil is still little explored, but it is extremely relevant for LGBT companies and professionals. Given the good psychometric qualities of the EEM-LGBT in the Brazilian context and the pioneering nature of investigating the construct in the country, it is important that research is carried out to seek further validity evidence based on the internal structure, through analyses of measurement invariance, as well as seeking validity evidence with external variables, such as work stress, depression, anxiety, job satisfaction, incivility, outness, self-esteem, well-being, work engagement, turnover intention, productivity and organizational support, in addition to considering larger and more homogeneous samples.

REFERENCES

Alexandre, N. M. C., & Coluci, M. Z. O. (2011). Validade de conteúdo nos processos de construção e adaptação de instrumentos de medidas. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 16(7), 3061-3068. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000800006 [ Links ]

Bandeira, D. R., & Hutz, C. S. (2020). Elaboração ou adaptação de instrumentos de avaliação psicológica para o contexto organizacional e do trabalho: Cuidados psicométricos. Em C. S. Hutz, D. R. Bandeira, C. M. Trentini, & A. C. S. Vazquez (Orgs.), Avaliação psicológica no contexto organizacional e do trabalho (pp. 13-18). Artmed. [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Bandeira, D. R. (2012). Adaptação e validação de instrumentos psicológicos entre culturas: Algumas considerações. Paidéia, 22(53), 423-432. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272253201314 [ Links ]

Brown, T. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford. [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., Brum, G. M., Zoltowski, A. P. C., Dutra-Thomé, L., Lobato, M. I. R., Nardi, H. C., & Koller, S. H. (2020). Experiences of discrimination and inclusion of Brazilian transgender people in the labor market. Revista Psicologia: Organização & Trabalho, 20(2), 1040-1046. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2020.2.18204 [ Links ]

Covas, F. S. N., & Bergamini, L. M. (2021). Análise crítica da linguagem neutra como instrumento de reconhecimento de direitos das pessoas LGBTQIA+. Brazilian Journal of Development, 7(6), 54892-54913. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n6-067 [ Links ]

Kovacic, D. (2019). Using the content validity index to determine content validity of an instrument assessing health care providers’ general knowledge of human trafficking. Journal of Human Trafficking, 4(4), 327-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2017.1364905 [ Links ]

Li, C. H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48(3), 936-949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7 [ Links ]

Medina, A. (2022). The impact workplace microaggressions have on those who identify as lesbian, gay and bisexual (Dissertação de doutorado). National Louis University. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1764&context=diss [ Links ]

Mendes, W. G., & Silva, C. M. F. P. (2020). Homicídios da população de lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis, transexuais ou transgêneros (LGBT) no Brasil: Uma análise espacial. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25(5), 1709-1722. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020255.33672019 [ Links ]

Nadal, K. L. (2019). A decade of microaggression research and LGBTQ communities: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1539582 [ Links ]

Nadal, K. L., Wong, Y., Issa, M., Meterko, V., Leon, J., & Wideman, M. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5(1), 21-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2011.554606 [ Links ]

Palo, S., & Jha, K. K. (2020). Queer at work. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Papadaki, V., Papadaki, E., & Giannou, D. (2021). Microaggression experiences in the workplace among Greek LGB social workers. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(4), 512-532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1892560 [ Links ]

Parr, N. J., & Howe, B. G. (2019). Heterogeneity of transgender identity nonaffirmation microaggressions and their association with depression symptoms and suicidality among transgender persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(4), 461-474. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000347 [ Links ]

Redcay, A., Luquet, W., & Huggin, M.E. (2019). Immigration and asylum for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 4, 248-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-019-00092-2 [ Links ]

Resnick, C. A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). Assessing experiences with LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: Development and validation of the microaggression experiences at work scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1380-1403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1542207 [ Links ]

Richard, D. (2021). Workplace microaggressions experienced by sexual minorities: Relationships to workplace attitudes, mental health, and the role of emotional distress tolerance (Dissertação de doutorado). University of Southern Mississippi. https://aquila.usm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2929&context=dissertations [ Links ]

Salgado, A. G. A. T., Araújo, L. F., Santos, J. V. O., Jesus, L. A., Fonseca, L. K. S., & Sampaio, D. S. (2017). LGBT old age: An analysis of the social representations among Brazilian elderly people. Ciencias Psicológicas, 11(2), 155-163. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v11i2.1487 [ Links ]

Silva, D. W. G., Castro, G. H. C., & Siqueira, M. V. S. (2021). Ativismo LGBT organizacional: Debate e agenda de pesquisa. Revista Eletrônica de Ciência Administrativa, 20(3), 434-462. https://doi.org/10.21529/RECADM.2021015 [ Links ]

Sooknanan, V. (2023). An investigation of LGBTQ+-specific workplace microaggressions: Their impact on job engagement and the buffering effects of organizational trust and identity disclosure (Dissertação de mestrado). Western University. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/9409/ [ Links ]

Souza, E. R., Ispas, D., & Weselman, E. D. (2017). Workplace discrimination against sexual minorities: Subtle and not-so-subtle. Canadian Jornal of Administrative Sciences, 34(2), 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1438 [ Links ]

Supremo Tribunal Federal. (2019). STF enquadra homofobia e transfobia como crimes de racismo ao reconhecer omissão legislativa. Jusbrasil. https://stf.jusbrasil.com.br/noticias/721650294/stf-enquadra-homofobia-e-transfobia-como-crimes-de-racismo-ao-reconhecer-omissao-legislativa [ Links ]

Valentini, F., & Damásio, B. F. (2016). Variância média extraída e confiabilidade composta: Indicadores de precisão. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-3772e322225 [ Links ]

Zanin, H. S. (2019). Fomento à economia pelas políticas públicas e o respeito aos direitos fundamentais: Acesso ao trabalho pelas minorias sexuais e de gênero. Revista Contribuciones a la Economía, 2019(2), 1-9. [ Links ]

How to cite: de Sousa Zarife, P., & Ribeiro, C. (2023). Adaptation and validity evidence of LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale in Brazil. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-3053. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3053

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. P. S. Z. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; C. R. in a, b, c, d.

Received: September 20, 2022; Accepted: October 26, 2023

texto en

texto en