Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Ciencias Psicológicas

Print version ISSN 1688-4094On-line version ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.2 Montevideo Dec. 2023 Epub Dec 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2867

Original Articles

The mediation of work engagement in resource relations with job crafting

1 Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Brazil, evanialouro@gmail.com

2 Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Brazil

The Work Demands and Resources Model advocates the existence of a positive relationship between resources and job crafting, and the mediation of work engagement. This study aimed to understand the relationship between social support at work (work resource) and the fear of missing out at work (emotional state) with the factor increasing job crafting resources, as well as the mediating role of work engagement. The sample consisted of 703 workers from different professions and of both sexes (90.6 % female). The results of the structural equation modeling showed that social support at work, fear of missing out at work, and work engagement were positively related to the job crafting resource increase factor. Work engagement partially mediated the positive relationship between social support at work and fear of missing out at work and the factor increasing job crafting resources. These results offer different theoretical and practical contributions to the field of organizational psychology, allowing for advances in knowledge about the nomological network of relationships between social support at work and fear of being disconnected with job crafting, with engagement as a mediator.

Keywords: social support at work; fear of missing out at work; work engagement; job crafting; JD-R Model.

O Modelo de Demandas e Recursos do Trabalho preconiza a existência de relação positiva entre recursos e o job crafting, e a mediação do engajamento laboral. O presente trabalho objetivou compreender as relações do suporte social no trabalho (recurso do trabalho) e do medo de estar desconectado do trabalho (estado emocional) com o fator aumento de recursos do job crafting, além do papel mediador do engajamento laboral. A amostra compôs-se de 703 trabalhadores de diversas profissões e de ambos os sexos (90,6 % sexo feminino). Os resultados na modelagem de equações estruturais demonstraram que o suporte social no trabalho, o medo de estar desconectado do trabalho e o engajamento laboral relacionaram-se positivamente com o fator aumento de recursos do job crafting. O engajamento laboral mediou parcialmente a relação positiva do suporte social no trabalho e do medo de estar desconectado do trabalho com o fator aumento de recursos do job crafting. Tais resultados oferecem diferentes contribuições teóricas e práticas para a área da psicologia organizacional permitindo o avanço no conhecimento sobre a rede nomológica das relações do suporte social no trabalho e do medo de estar desconectado com o job crafting, tendo o engajamento como mediador.

Palavras-chave: suporte social no trabalho; medo de estar desconectado do trabalho; engajamento no trabalho; job crafting; modelo JD-R.

El modelo de Demandas y Recursos del Trabajo aboga por la existencia de una relación positiva entre los recursos y el job crafting, y la mediación del compromiso laboral. El presente trabajo tuvo como objetivo entender las relaciones del apoyo social en el trabajo (recurso laboral) y del miedo a estar desconectado del trabajo (estado emocional) con el factor de aumento de recursos del job crafting, además del rol mediador del compromiso laboral. La muestra consistió en 703 trabajadores de diversas profesiones y de ambos sexos (90.6 % mujeres). Los resultados en el modelado de ecuaciones estructurales demostraron que el apoyo social en el trabajo, el miedo a estar desconectado del trabajo y el compromiso laboral se relacionaron positivamente con el factor de aumento de recursos del job crafting. El compromiso laboral medió parcialmente la relación positiva del apoyo social en el trabajo y del miedo a estar desconectado del trabajo con el factor de aumento de recursos del job crafting. Tales resultados ofrecen diferentes contribuciones teóricas y prácticas para el área de la psicología organizacional y permitien avanzar en el conocimiento sobre la red nomológica de las relaciones del apoyo social en el trabajo y del miedo a estar desconectado con el job crafting, con el compromiso como mediador.

Palabras clave: apoyo social en el trabajo; miedo a la desconexión del trabajo; compromiso laboral; job crafting; modelo JD-R.

With the evolution of work complexity and the acceleration of organizational changes motivated by the rapid advance of technology, globalization, digital work, and new market demands, organizations have been pressured to become more agile, flexible, and efficient (Baard et al., 2014; Campaner et al., 2022). The same factors that have driven organizational change have also led to changes in work processes, motivated by the need to obtain more engaged productive, and adaptable employees (Baard et al., 2014; van den Heuvel et al., 2020).

As a result, the old ways of outlining and organizing work, which modeled work from the top down, began to prove inefficient. As a result, bottom-up decision-making models emerged, in which employees became more autonomous. In other words, organizations began to value employees who were able to adapt more quickly to changes. The focus of organizations has shifted to those who are more versatile and creative, thus altering their work by adopting job crafting behaviors, a phenomenon known as job crafting (Lee et al., 2017; van den Heuvel et al., 2020). Thus, the term "job crafting" has been used in Brazil as job crafting (Chinelato et al., 2015; Pimenta de Devotto et al., 2022).

Job crafting consists of self-initiated changes by employees in order to adjust work activities to their preferences, motivations, skills, and competencies, as well as to match work resources and demands with their needs and abilities (Tims & Bakker, 2010; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). The Job Demands and Resources Model (JD-R) is used to understand well-being at work and the risk factors associated with burnout and work engagement. According to this model, while work demands, such as high workload and pressure, can be sources of stress and burnout, work resources, such as social support at work and autonomy, help to mitigate these demands and promote engagement. These resources and demands are influenced by antecedents, such as individual and organizational characteristics, and can lead to different consequences, including impacts on health and performance (Bakker et al., 2023). For this model, job crafting is a consequential variable that is influenced by contextual and personal resources and work motivation variables, such as work engagement (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Based on this model, different empirical studies have shown that job crafting is influenced by contextual factors such as support from supervisors and colleagues, feedback, and autonomy, as well as personal factors such as self-efficacy, optimism, and self-esteem (Demerouti & Bakker, 2011). Thus, based on the JD-R Model, this study sought to ascertain the relationship between job crafting and variables whose relationship with this construct had already been investigated, adding to the model the fear of missing out at work (FoMO). This construct was included in the research model due to its importance in the organizational context, in terms of operationalizing fear as an influencer of individual interventions in workplace behavior in order to avoid potential resource loss. In this sense, the aim of this investigation was to test the direct relationship between social support at work (work resource) and the fear of missing out at work (emotional state) due to job crafting, with work engagement as the mediator of these relationships.

FoMO is defined as the generalized apprehension that a person may lose valuable career opportunities if they are absent or disconnected from work (Budnick et al., 2020). Przybylski et al. (2013) sought to understand the fear of missing out based on the Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), according to which the individual's psychological needs (such as autonomy, personal initiative; competence, the ability to act; and relationship, connection with other people) can affect choices and determine behavior. In this sense, the fear of missing out has been understood as an emotional state of self-regulation caused by not fulfilling these psychological needs. Thus, empirical studies have shown that the lack of psychological needs can cause the fear of missing out (Beyens et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2018; Oberst et al., 2017; Przybylski et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2018).

Thus, FoMO was inserted into the research model as an emotional state that can act as a motivator for the search for connection, information, and engagement in the workplace. The fear of missing out on opportunities or being excluded can serve as a stimulus for workers, encouraging them to act to avoid a lack of resources at work (Budnick et al., 2020). From this perspective, FoMO, in the work context, represents an emotional state that encourages employees to remain engaged in their responsibilities, aiming to meet their psychological needs, such as the ability to intervene positively in the environment, autonomy, and connection with coworkers (Przybylski et al., 2013). That said, according to Self-Determination Theory, the emotional state of fear of missing out can trigger positive control since the search for social connections and interpersonal relationships can serve as an intrinsic motivator (Przybylski et al., 2013). FoMO, by encompassing the constant worry of missing out on social opportunities and the longing to maintain connections with other people, can stimulate the drive to maintain relationships and strengthen the sense of belonging to social groups. In this way, FoMO can amplify the motivation to pursue the fulfillment of personal needs (Gupta & Sharma, 2021).

On this subject, the study by Nursodiq et al. (2020) highlighted the beneficial side of FoMO in education, suggesting that if students channeled the fear of missing out on information and the anxiety of falling behind colleagues at academic events as a stimulus, this could be advantageous for academic life. In this sense, this study seeks to extend the nomological network of job crafting by including an emotional state as an antecedent. It also provided additional empirical evidence for the JD-R Model by including an emotional state as a possible driver of the motivational process.

In addition, in divergence with the assertions advocated in the JD-R Model, different studies have found that job crafting is an independent variable in a mediational research model (Aldrin & Merdiaty, 2019; Garg et al., 2021; Letona-Ibañez et al., 2021; Llorente-Alonso & Topa, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2019; Pradana & Suhariadi, 2020; Shin et al., 2018). Other research has also highlighted the mediating role of job crafting in the relationship between work resources and work outcomes (Chang et al., 2021; DuPlessis et al., 2021; Pimenta de Devotto et al., 2020; Robledo et al., 2019).

Only two studies were found with job crafting as the dependent variable. Chen's (2019) study showed that work resources are positively related to work engagement and that this is positively associated with job crafting. The research by Chinelato et al. (2020) showed that the perception of psychological safety contributed to the satisfaction of psychological needs, which in turn had an impact on job redesign. Seeking additional empirical evidence for the JD-R Model, according to which job redesign is one of the outcome variables of the motivational process, the current investigation sought to test job redesign as a consequent variable in a mediational research model.

This study makes different contributions to the field of Organizational and Work Psychology. The first refers to the inclusion of the fear of missing out at work as an antecedent of work engagement and job crafting. In addition, constructs such as fear of missing out at work, social support at work, engagement, and job crafting were not investigated together. The third contribution of the study is the testing of a mediation model that has not yet been empirically verified, with job crafting as a consequent variable. Finally, a deeper understanding of the relationships between the above-mentioned constructs can also be useful for organizations and their managers in implementing solutions aimed, in addition to professional improvement, at promoting engagement at work and proactive behavior that can improve organizational performance. Such solutions can be disseminated by drawing up programs and policies relating to people management aimed at developing individuals and positive relationships in the workplace.

The Fear of Missing Out at Work and Job Crafting

Job crafting can be defined as proactive changes that employees make to their own work tasks and relationships, through a cognitive process that leads to a change in the way they view their own work, in order to make it more meaningful (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). From the perspective of the JD-R Model, the proactive changes that characterize job crafting concern the optimization of work demands and resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2018; Tims et al., 2012).

According to Petrou et al. (2012), job crafting is a multidimensional construct, made up of three dimensions: increasing resources, increasing challenging demands, and reducing work demands. The first dimension refers to proactively seeking help at work to support the accomplishment of objectives, thus generating motivational behaviors with positive results for the employee's well-being. The increase in challenging demands, in turn, is positively related to motivational results at work with beneficial effects on well-being. This is because challenges at work are no longer perceived as bad characteristics of the job, but rather as motivational drivers that serve as stimuli for carrying out work activities. Finally, reducing work demands is associated with behaviors that seek to minimize the mental, emotional, and physical aspects or the workload and pressure that affect the energy draining and motivation process.

Based on the Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 2001), which states that individuals, faced with the possibility of losing resources, take action to maintain, protect, and develop resources, this study focused on only one dimension of job crafting, the increase in resources. In addition to the Conservation of Resources Theory, the justification for choosing just this aspect is that it is associated with proactive coping which results in positive outcomes for the employee, such as motivation and well-being (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008).

According to the JD-R Model, personal resources refer to individual characteristics that provide intrinsic motivation to carry out demands (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007), seeking desirable results (Bakker et al., 2014) that impact job crafting (Tims & Bakker, 2010). In this study, it was postulated that FoMO may play a similar role to personal resources in the research model since the fear of missing out on opportunities can motivate individuals in their work context. This construct is associated with the fear that a person may feel that other people are having more rewarding experiences than themselves (Budnick et al., 2020). This study addresses this phenomenon in relation to the context of work, however, the construct was initially addressed and has been studied in the context of social networks and concerns the fear of being disconnected from these networks (Riordan et al., 2018). Budnick et al. (2020), noting a lack of studies on FoMO in relation to the work environment, introduced it into this context.

Budnick et al. (2020) defined the fear of missing out at work as the generalized apprehension that the employee may miss out on valuable career opportunities when absent or disconnected from work, compared to their colleagues. In this sense, in this research, FoMO is analyzed as an emotional state originating from this generalized apprehension and which arises as an immediate and urgent response to an unstable or threatening situation perceived at work.

Fear is a spontaneous and natural reaction, conscious or not, inherent to the individual, and derives from concern about facing something new and unexpected. Individuals with a fear of missing out have a need to know what others are experiencing (Chai et al., 2018). Similarly, the fear of missing out at work leads employees to stay connected to work, for fear of missing out on some resources, such as information or participation in decision-making (Budnick et al., 2020). Thus, fearful individuals invest more in physical, cognitive, and emotional behaviors. And, as a result, they experience emotions, which will trigger high levels of dedication at work, leading them to carry out extra actions that are not defined in their work routine (Bakker et al., 2014; Chai et al., 2018).

It stands to reason, then, that high levels of FoMO in the workplace can generate more interactional behaviors of frequent communication and information exchange between employees. Such behaviors would ultimately lead to an increase in the employee's intrinsic motivation since employees tend to act actively in the workplace by making choices and negotiating tasks that seem most meaningful to them. This means that the fact that the person does not want to disconnect from work will act as a facilitator of the work aspects, as it helps employees to deal with situations that require energy and dedication, which can make them have a proactive behavior of increasing specific resources (Bakker et al., 2014; Petrou et al., 2018).

In this sense, previous studies (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Kim & Beehr, 2021; Tims & Bakker, 2010; van Wingerden et al., 2017; Vogt et al., 2016) have shown positive relationships between personal characteristics and job crafting. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 1: FoMO in the workplace is positively associated with increased redesign resources at work.

Social Support at Work and Job Crafting

According to the JD-R Model, work resources can be defined as inputs that help workers achieve their goals, fulfill their tasks, and develop personally and professionally (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). In the current research, social support at work was adopted as a resource, which relates to individuals' perception of the existence and availability of social support and the quality of interpersonal relationships with managers and colleagues (Tamayo & Trócolli, 2002). This construct can be explained by the fact that this phenomenon is seen as a resource that can reduce stress and cope with work situations (Collins, 2008). Furthermore, from the JD-R Model perspective, social support at work is characterized as a work resource that triggers an extrinsic motivational process from which positive consequences result (Bakker et al., 2004). It contributes to the achievement of work-related goals (Boyd et al., 2011), as well as reducing work demands and stimulating personal growth and development (Demerouti et al., 2001). In other words, social support at work generates a motivational process that can create favorable conditions for employees to let go of old habits and reframe old ways of working. In this way, the more social support at work is perceived by employees, the more likely they are to develop positive proactive attitudes and behaviors (Chang et al., 2021).

Different cross-sectional or diary studies, such as Audenaert et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; and Rudolph et al., 2017, have shown that social support is positively associated with redesign at work. Based on the JD-R Model and the available empirical evidence, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 2: Social support is positively associated with increased redesign resources at work.

Engagement at Work and Job Crafting

Work engagement can be defined as a positive and satisfying psychological state related to work, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Vigor refers to high levels of energy and mental resilience while carrying out work activities; dedication is associated with involvement in work which translates into a sense of meaning, enthusiasm, and challenge at work; and finally, absorption refers to concentration, happiness, and immersion in work, which leads the employee to not notice time passing, thus becoming detached from work.

Engaged employees therefore have high levels of energy and enthusiasm, as well as being more focused on their work responsibilities. In this sense, they tend to pursue activities that go beyond their responsibilities, as they feel able to embrace new goals (Bakker et al., 2014). In addition, more engaged employees identify with their tasks and strive to produce more positive results for their professional growth and the pursuit of good results for the organization (Siqueira et al., 2014).

Concerning the relationship between work engagement and job crafting, Bakker (2011) argues that engaged employees tend not to be passive, but rather proactive in changing their work environment as necessary. In this way, they tend to act actively in their work context, choosing tasks and negotiating their content in order to give their work more meaning. Corroborating these assertions, the study by Tims et al. (2013) observed a positive relationship between the constructs. Given the above, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 3: Engagement at work is positively associated with an increase in crafting resources at work.

Mediating Engagement at Work

The JD-R Model predicts the possibility of a virtuous spiral linking personal and work resources with engagement, which in turn is associated with job crafting (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). In this sense, both work resources and personal resources enable employees to balance their work demands in a positive way (van Wingerden et al., 2017). Therefore, the availability of resources is a key factor in generating engagement at work (Tims & Bakker, 2010). Engaged employees tend to more often exhibit the proactive behaviors of actively changing their tasks which constitutes job crafting (Bakker, 2011).

The JD-R Model therefore predicts a feedback process in which the increase in resources, both personal and work-related, makes employees more engaged, which leads them to put more effort into their tasks. As a result, they end up looking for new resources by adopting job crafting actions that lead them to take new initiatives and create solutions to the challenges that arise in their day-to-day work (Bakker, 2011). In other words, engaged employees look for more resources to help them carry out their work, which leads them to promote changes in their activities, such as creating new ways of solving tasks (Bakker et al., 2014).

Engagement at work thus plays a mediating role between personal and work resources and job crafting. In this study's particular case, therefore, work engagement is expected to mediate the relationship between social support at work, as a work resource, and FoMO at work, as a personal resource, with the resource-increasing factor of job crafting.

In line with these considerations, studies have shown the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between personal resources and work outcomes (van Wingerden et al., 2017) and in the relationship between work resources and work outcomes (Ananthram et al., 2018; Chen, 2019; Garg et al., 2021; Nasurdin et al., 2018). That said, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 4: Work engagement mediates the positive relationship of workplace FoMO with increased job crafting resources.

Hypothesis 5: Work engagement mediates the positive relationship between social support and increased job crafting resources.

Method

Participants

The convenience sample consisted of 703 Brazilian workers of various professions and both sexes (90.6% female), from 25 Brazilian states plus the Federal District, the majority being centered in the states of São Paulo (31.4 %) and Rio de Janeiro (17.5 %). The participants' ages ranged from 18 to 71 years (M = 45.1; SD = 9.9); working time in their current job ranged from 1 to 40 years (M = 9.8; SD = 8.6) and total working time ranged from 1 to 52 years (M = 20.1; SD = 12.9). Most of the participants earned between 1 and 3 minimum wages (49.9 %) and between 3 and 5 minimum wages (32.9 %). Most of the participants worked in the public sector (55.2 %) and had different jobs (civil servant, teacher, salesperson, among others). In terms of education, 50.6 % had a postgraduate degree (stricto or latu sensu) and 24.0 % had completed higher education. As for marital status, most were married or living as married (61.0 %) and had children (71.8 %). For inclusion in the study, the criteria used were that the participant was working, was at least 18 years old, and had at least one year's experience in their respective job.

Instruments

Fear of Missing Out at Work Scale, by Budnick et al. (2020), adapted to the Brazilian scenario by Louro et al. (2022), consisting of 10 items, to be answered on five-point Likert-type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These items are equally divided into two dimensions: relational exclusion and informational exclusion. Examples of items: “I worry about missing out on the networking opportunities my colleagues will have” (relational exclusion); “I worry about missing out on valuable information relating to my work” (informational exclusion). In this study, based on the parsimony principal according to which scientific writing should be based on simplicity and the use of premises or hypotheses that are strictly necessary to explain a phenomenon (Volpato, 2007), a single-factor version was used, consisting of the 10 items of the instrument. The internal consistency indices were .94 (Cronbach's Alpha) and .97 (McDonald's Omega) in this study.

The social support at work subscale of the Perceived Organizational Support Scale, developed by Tamayo et al. (2000), made up of five items, answered using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to always (5). Example item: “My group cares about the well-being of co-workers”. In the current survey, the internal consistency indices were .89 (Cronbach's Alpha) and .93 (McDonald's Omega).

Work Engagement Scale (UWES), in its reduced version, created by Schaufeli and Bakker (2003), adapted for the Brazilian scenario by Ferreira et al. (2016), composed of nine items, to be answered on seven-point Likert-type scales, ranging from never (0) to daily (6). Example item: “In my work, I feel full of energy”. In the current study, the internal consistency indices were .94 (Cronbach's Alpha) and .96 (McDonald's Omega).

Resource-seeking behavior subscale of the Revised Scale of Job Crafting Behaviors, generated by Petrou et al. (2012), adapted to the Brazilian context by Silva Junior (2018). It consists of four items, to be answered on a Likert-type scale, ranging from 'never' (1) to 'often' (5). Example item: "I ask my colleagues for advice". The internal consistency indices of the instrument factor in this investigation were equal to .70 (Cronbach's Alpha) and .75 (McDonald's Omega). A Sociodemographic Questionnaire was also used with questions about the characteristics of the sample.

Collection procedures

The data was collected through questionnaires applied entirely online, using Google Forms, to workers contacted through the researchers' social networks and accessed via WhatsApp, email, Facebook, Instagram, or LinkedIn. The questionnaires took approximately 20 minutes to be completely answered.

Data Analysis Procedures

Initially, the data collection instruments were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis using Mplus software version 8.1. Subsequently, the indices of the measurement model, in which each construct was inserted, were calculated to check whether the items were explained by their respective variables. The factor correlations between the study variables and the instruments' internal consistency indices were also checked in this measurement model. Finally, the hypothetical model was tested using Structural Equation Modeling. To assess how well the model fits the data, the following indicators were used: chi-square (χ²), Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Values below .08 for the RMSEA and values greater than .90 were considered satisfactory for the CFI and TLI (Byrne, 2012).

Considering that the data collection was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which Brazilian workers were working in person or remotely (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2020), the work modality variable was inserted as a control variable. The aim of using this variable as a control was to prevent it from interfering with the relationship between the independent variables and the criterion variable.

Ethical Procedures

The research was initially submitted to the institution's Research Ethics Committee and approved: Certificate of Submission for Ethical Appraisal 47212921.7.0000.5289. The research participants were given online access to information about the possible benefits and risks of the procedures that were carried out, as well as all of the other relevant information. When they voluntarily chose to take part, they accepted the Free and Informed Consent Term and then began to fill in the answers to the questionnaires, which were then recorded and sent to the research database. All participants were assured of the confidentiality of the information provided.

Results

Measurement Model

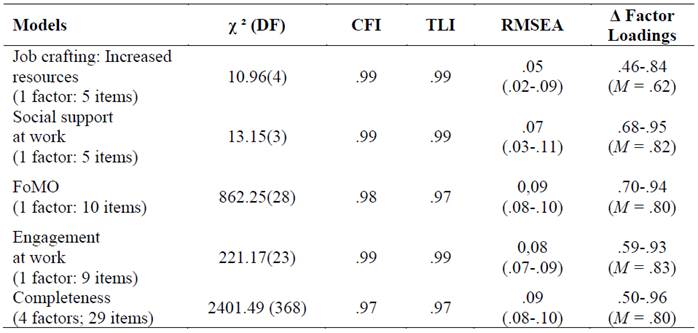

Initially, Confirmatory Factor Analyses were carried out for each scale, followed by an analysis of the measurement model. In this analysis, the FoMO Scale was considered to be unifactorial, in accordance with the parsimony principle (Volpato, 2007). The structure of the instruments was confirmed, with all the items retained and good fit indices obtained. The measurement model also showed good fit indices, thus demonstrating that the items can be explained by their respective latent variables (Table 1).

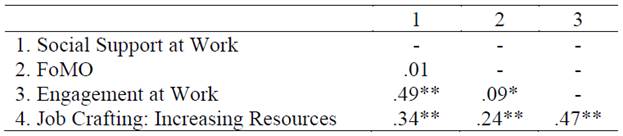

Table 1: Fit Indices and Variation of Factor Loadings of the Models Tested

Notes: χ ²: chi-square; DF: degrees of freedom; CFI: Comparative Fix Index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; Δ: variance.

The factor correlation between the variables was also analyzed in the measurement model. There was a significant correlation between the study variables, with the exception of the association between the independent variables: Social Support at Work and FoMO (Table 2).

Hypothesis Testing

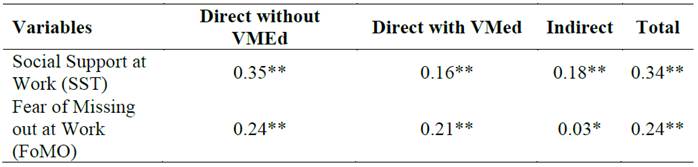

When testing the relationship between the variables, it was found that the "type of work" did not significantly affect the main results. The final analyses were therefore carried out without this control variable. In testing the hypotheses, the direct effect of VIs on DV was first tested (without the mediating variable). The results showed a positive and significant effect of the independent variables, Fear of missing out at work (FoMO) and Social Support at Work (SST), on the dependent variable, Increased Resources (AR), as follows: FoMO(AR: β = 0.24; p < .001; SST(AR: β = 0.35; p < .001. These results confirmed the study's Hypotheses 1 and 2.

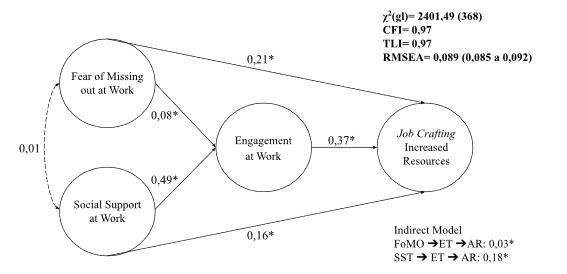

Subsequently, the direct effect of VIs on VD was tested (with the mediating variable). The inclusion of the mediating variable Work Engagement (WE) in the model showed that the independent variables had positive and significant associations with this variable (FoMO ( WE: β = 0.08; p < .05; and SST(ET: β = 0.49; p < .001) and that the relationship between the mediating variable and the dependent variable (β = 0.37; p< .001) was also positive and significant. It was also found that in the presence of the mediating variable, the independent variables maintained positive and significant associations with the dependent variable (FoMO ( AR: β = 0.21; p < .001; and SST(AR: 0.16; p < .001). These results provided empirical support for the study's Hypothesis 3.

Finally, in the test of indirect effects between the independent variables, the mediating variable, and the dependent variables, the results were positive and significant (FoMO ( ET ( AR: β = 0.03; p < .05); SST ( ET ( AR: β =0.18; p < .001). Considering that, in the presence of the mediating variable, the effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable were reduced, but remained significant, it can be said that work engagement partially mediated both relationships. These results therefore support Hypotheses 4 and 5 of the study (Table 3; Figure 1).

Table 3: Results of the mediational model analysis

Note: VMed: Mediating Variable. * p < .05 ** p < .001

Discussion

This study assessed the direct effect of social support at work and the fear of missing out at work on the factor of increasing job crafting resources, as well as seeking to verify the mediating role of work engagement in these relationships. In this regard, the aim was to verify whether individuals who have support in their workplace and who feel fear of missing out on opportunities tend to be more engaged and are led to increase their work resources. The results found have important theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical Implications

The results showed that the FoMO variable was positively associated with the increase in job crafting resources, which fully supported Hypothesis 1. This result converges with previous findings that have also concluded that personal characteristics are positively related to job crafting (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Kim & Beehr, 2021; Tims & Bakker, 2010; van Wingerden et al., 2017; Vogt et al., 2016) and shows that the fear of missing out on relationships and information can motivate employees to stay connected to their work by acting proactively in order to avoid losing resources, keep them or protect them (Budnick et al., 2020; Hobfoll, 2001). It should be noted, however, that FoMO in the workplace, when in excess, can be considered negative as it causes the person, for example, to constantly check their messages so as not to miss some important aspect of the job. In this sense, although not tested in this study, it is important to note that FoMO in the workplace can also be related to health problems, such as tension at work; telepressure; burnout; social anxiety trait, and neuroticism (Budnick et al., 2020). Despite this, the results obtained here allow for the conclusion that FoMO can provide behavioral benefits in terms of "motivational resources" that predict more work-related communications from employees and overall engagement at work (Budnick et al., 2020).

The analyses also showed that social support was positively associated with an increase in job crafting resources, providing empirical support for hypothesis 2. A possible explanation for this result lies in the fact that social support at work manifests an extrinsic motivational process causing positive consequences (Bakker et al., 2004) and an intrinsic one satisfying the basic psychological needs of relationships, which leads employees to develop positive proactive attitudes and behaviors by redesigning their own work (Audenaert et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Rudolph et al., 2017).

The findings also showed that work engagement was positively associated with an increase in job crafting resources, which made it possible to confirm hypothesis 3. Engagement at work contributes to greater involvement and commitment to the activities carried out in the company (Bakker et al., 2014; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Job crafting, in turn, is associated with the belief that it is possible to find a broader meaning to what you do at work (Bakker, 2011). Through proactive attitudes, motivated employees will change the scope of their work activities in order to do things that are more meaningful and in line with their abilities and personal interests (Tims et al., 2013).

The results indicated that work engagement partially mediated the positive relationship of FoMO and Social Support at Work with the increase in job crafting resources, which supported hypotheses 4 and 5 of the study. These findings are in line with studies that have pointed to the mediating role of work engagement in the relationships of personal resources (van Wingerden et al., 2017) and work resources (Ananthram et al., 2018; Chen, 2019; Garg et al., 2021; Nasurdin et al., 2018; Shin et al., 2018) with work outcomes. In addition, the present results contribute to a better clarification of the mediational role played by work engagement in the association between personal and work resources with proactive behaviors, as advocated by the JD-R Model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017).

It should be noted, therefore, that this study presented important theoretical implications with regard to the analysis of the JD-R Model. One contribution relates to the use of fear of missing ou on work as an antecedent variable. Another important theoretical evidence of the aforementioned model was the fact that this study focused on job crafting as a consequent variable in a mediational research model, a relationship that has been neglected in previous studies using this construct and the JD-R Model (e.g. Aldrin & Merdiaty, 2019; Chang et al., 2021; DuPlessis et al., 2021; Garg et al., 2021).

Practical Implications

In addition to the theoretical implications highlighted above, this study reveals some practical implications. The findings obtained in this study can help organizations diagnose the need to value work resources as a bridge that will encourage engagement at work and, consequently, lead to an increase in their employees' proactive behavior.

This means that although job crafting is a proactive behavior that is carried out individually from the bottom up, organizations can encourage the adoption of such behaviors permanently by promoting initiatives that will help motivate employees. This can be done through motivational strategies aimed at professional improvement, with increased resources and social support at work to promote engagement in regular tasks. With regard to FoMO, although the study showed a positive relationship between the construct and job crafting, managers should be concerned about preventing this state of apprehension on behalf of employees. For example, the study by Chinelato et al. (2020) showed a positive association between psychological safety and job crafting. Thus, when managers notice the presence of FoMO among their employees, they can disseminate relevant information about the organization among them in order to reduce this state of psychological apprehension, provide a more psychologically safe work environment and also promote job crafting behaviors. These strategies will therefore enable employees to rethink the work environment in a way that best suits them and the organization, aligning its members' personal needs with the organizational focus.

Limitations and Future Studies

This study revealed some limitations. The first was the cross-sectional nature of the study, which makes it impossible to establish causal relationships between the variables studied and can lead to common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, the items dealt with different variables, as observed in the analysis of the measurement model, which can help to avoid biased responses (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Another limitation was the matter of where the participants lived. Although the participants belonged to 25 states, plus the Federal District, there was a large concentration in the Southeast, which may make generalizing the results to other Brazilian regions difficult. Furthermore, this study included more female participants, which makes it difficult to analyze the gender balance. It would therefore be beneficial for future studies to be conducted with more equal samples.

In addition, future research could go deeper into the nomological network of the job crafting construct, especially with regard to the relationship between other personal resources (e.g. generalized self-efficacy, self-reported evaluations) and work resources (e.g. job autonomy, types of leadership) and motivational variables (e.g. flourishing at work, job satisfaction and other indicators of well-being at work) with this construct. The research suggested here should be longitudinal in nature and include job performance as a consequence of job crafting, a relationship not explored in this study. Furthermore, the investigation of professionals segmented by organization could contribute to a deeper understanding of the subject. In addition, a suggestion for further studies could be to investigate the FoMO construct more deeply, with a view to testing FoMO with some negative variables in the work context, such as addiction to work, burnout, and illness.

Final Considerations

Despite its limitations, this study presented important empirical evidence on the JD-R Model, since it used a model of relationships between the use of fear of missing work as a personal resource and the job crafting construct as a consequent variable in a mediational research model, thus adding to and reinforcing this under-investigated thesis. Furthermore, this research proves to be innovative in the Brazilian scenario, as it investigated the subject of FoMO in the workplace and its relationship with the resource-enhancing factor of job crafting.

By analyzing the results obtained, this research opens up new avenues for future investigations into the operationalization of FOMO in the organizational environment and the importance of social support at work. Both factors have been shown to boost motivation and can therefore be considered drivers of job crafting behaviors.

Finally, it is important to point out that the continuous increase in technological adoption in organizations is a growing and inevitable truth, a scenario that has led people to remain connected most of the time. This means that, to a certain extent, people, for fear of missing out on opportunities and information, may feel challenged to engage in new ventures, as evidenced by this study's findings. In addition, social support at work is a fundamental resource for accomplishing tasks, as it is expected that employees who are supported in their work environment will feel more secure and thus develop more proactive behaviors at work (Chen et al., 2021).

REFERENCES

Aldrin, N., & Merdiaty, N. (2019). Effect of job crafting on work engagement with mindfulness as a mediator. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1684421. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1684421 [ Links ]

Ananthram, S., Xerri, M. J., Teo, S. T. T., & Connell, J. (2018). High-performance work systems and employee outcomes in Indian call centres: A mediation approach. Personnel Review, 47(4), 931-950. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-09-2016-0239 [ Links ]

Audenaert, M., George, B., Bauwens, R., Decuypere, A., Descamps, A., Muylaert, J., Ma, R., & Decramer, A. (2020). Empowering leadership, social support and job crafting in public organizations: A multilevel study. Public Personnel Management, 49(3), 367-392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026019873681 [ Links ]

Baard, S. K., Rench, T. A., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2014). Performance Adaptation: A theoretical integration and review. Journal of Management, 40(1), 48-99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313488210 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 265-269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411414534 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309-328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273-285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2018). Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. Em E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 1-13). DEF Publishers. https://doi.org/nobascholar.com [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 389-411. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job Demands-Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 25-53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83-104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20004 [ Links ]

Beyens I., Frison E., & Eggermont S. (2016). I don’t want to miss a thing: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 64(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083 [ Links ]

Boyd, C. M., Bakker, A. B., Pignata, S., Winefield, A. H., Gillespie, N., & Stough, C. (2011). A longitudinal test of the job demands‐resources model among Australian university academics. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 60(1), 112-140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2010.00429.x [ Links ]

Budnick, C. J., Rogers, A. P., & Barber, L. K. (2020). The fear of missing out at work: Examining costs and benefits to employee health and motivation. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106161 [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus, basic concepts, applications and programming. Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Campaner, A., Heywood, J. S., & Jirjahn, U. (2022). Flexible work organization and employer provided training: Evidence from German linked employer‐employee data. Kyklos, 75(1), 3-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12283 [ Links ]

Chai, H., Niu, G., Chu, X., Wei, Q., Song, Y., & Sun, X. (2018). Fear of missing out: What have I missed again? Advances in Psychological Science, 26(3), 527-537. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.00527 [ Links ]

Chang, P. C., Rui, H., & Wu, T. (2021). Job autonomy and career commitment: A moderated mediation model of job crafting and sense of calling. SAGE Open, 11(1), 215824402110041. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211004167 [ Links ]

Chen, C., Feng, J., Liu, X. and Yao, J. (2021). Leader humility, team job crafting and team creativity: The moderating role of leader-leader exchange. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 326-340. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12306 [ Links ]

Chen, C.-Y. (2019). Does work engagement mediate the influence of job resourcefulness on job crafting? An examination of frontline hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1684-1701. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0365 [ Links ]

Chinelato, R. S. C., Tavares, S. M. O. M, Ferreira, M. C., & Valentini, F. (2020). Predictors of job crafting behaviors: A mediation analysis. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 36. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e3654 [ Links ]

Chinelato, R. S. d. C., Ferreira, M. C., & Valentini, F. (2015). Evidence of validity of the job crafting behaviors scale. Paidéia, 25(62), 325-332. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272562201506 [ Links ]

Collins, S. (2008). Statutory social workers: Stress, job satisfaction, coping, social support and individual differences. British Journal of Social Work, 38(6), 1173-1193. https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcm047 [ Links ]

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer. [ Links ]

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974 [ Links ]

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 [ Links ]

DuPlessis, J. H., Ellinger, A. D., Nimon, K. F., & Kim, S. (2021) Examining the mediating effect of job crafting on the relationship between managerial coaching and job engagement among electricians in the U.S. skilled trades. Human Resource Development International, 24(5), 558-585. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2021.1947696 [ Links ]

Ferreira, M. C., Valentini, F., Damásio, B. F., Mourão, L., Porto, J. B., Chinelato, R. S. de C., Novaes, V. P., & Pereira, M. M. (2016). Evidências adicionais de validade da UWES-9 em amostras brasileiras. Estudos De Psicologia (Natal), 21(4), 435-445. https://doi.org/10.5935/1678-4669.20160042 [ Links ]

Garg, N., Murphy, W., & Singh, P. (2021). Reverse mentoring, job crafting and work-outcomes: The mediating role of work engagement. Career Development International, 26(2), 290-308. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2020-0233 [ Links ]

Gupta, M., & Sharma, A. (2021). Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(19), 4881-4889. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.4881 [ Links ]

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: an International Review, 50(3), 337-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062 [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2020). O IBGE apoiando o combate à COVID-19. https://covid19.ibge.gov.br/pnad-covid/trabalho.php [ Links ]

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2021). The role of organization-based self-esteem and job resources in promoting employees’ job crafting behaviors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(19). 3822-3849. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1934711 [ Links ]

Lee, S.-H., Shin, Y., & Baek, S. I. (2017). The impact of job demands and resources on job crafting. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 33(4), 827. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v33i4.10003 [ Links ]

Letona-Ibañez, O., Martinez-Rodriguez, S., Ortiz-Marques, N., Carrasco, M., & Amillano, A. (2021). Job crafting and work engagement: The mediating role of work meaning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105383 [ Links ]

Llorente-Alonso, M., & Topa, G. (2019). Individual crafting, collaborative crafting, and job satisfaction: The mediator role of engagement. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 35(1), 217-226. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2019a23 [ Links ]

Louro, E. S., Ferreira, M. C., Gabardo-Martins, L. M. D., Martins, L. F. (2022). Evidências de validade da Escala do Medo de Estar Desconectado do Trabalho em amostras brasileiras. Trends in Psychology, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-022-00175-6 [ Links ]

Nasurdin, A. M., Ling, T. C., & Khan, S. N. (2018). Linking social support, work engagement and job performance in nursing. International Journal of Business and Society, 19(2) 363-386. [ Links ]

Nguyen, H. M., Nguyen, C., Ngo, T. T., & Nguyen, L. V. (2019). The effects of job crafting on work engagement and work performance: A study of Vietnamese commercial banks. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 6(2), 189-201. https://doi.org/10.13106/JAFEB.2019.VOL6.NO2.189 [ Links ]

Nursodiq, F., Andayani, T. R., & Supratiwi, M. (2020). When fear of missing out becomes a good thing. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 4477(International conference on community development (ICCD 2020), 254-259. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.201017.056 [ Links ]

Oberst, U., Wegmann, E., Stodt, B., Brand, M., & Chamarro, A. (2017). Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. Journal of Adolescence, 55(1), 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008 [ Links ]

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1766-1792. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315624961 [ Links ]

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1120-1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1783 [ Links ]

Pimenta de Devotto, R., Freitas, C. P. P. d., & Wechsler, S. M. (2022). Redesenho do trabalho de aproximação: Via de acesso ao engajamento no trabalho? Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.5935/rpot/2022.1.22542 [ Links ]

Pimenta de Devotto, R., Machado, W. L., Vazquez, A. C. S., & Freitas, C. P. P. (2020). Work engagement and job crafting of Brazilian professionals. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 20(1), 869-876. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2020.1.16185 [ Links ]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. M., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [ Links ]

Pradana, E., & Suhariadi, F. (2020). The effect of job crafting on innovative behavior through mediation work engagement. Airlangga Journal of Innovation Management, 1(1), 1-77. https://doi.org/10.20473/ajim.v1i1.19402 [ Links ]

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841-1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014 [ Links ]

Riordan, B. C., Cody, L., Flett, J. A. M., Conner, T. S., Hunter, J., & Scarf, D. (2018). The development of a single item FoMO (Fear of Missing Out) scale. Current Psychology, 39(1), 1215-1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9824-8 [ Links ]

Robledo, E., Zappalà, S., & Topa, G. (2019). Job crafting as a mediator between work engagement and wellbeing outcomes: A time-lagged study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(8), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081376 [ Links ]

Rudolph, C.W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N. and Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102(1), 112-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008 [ Links ]

Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(1), 116-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701763982 [ Links ]

Schaufeli W. B., & Taris T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. Em G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach (pp. 43-68). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4 [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). UWES: Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Test manual. Utrecht University, Department of Psychology. http://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(1), 293-437. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248 [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326 [ Links ]

Shin, Y., Hur, W.-M., & Choi, W.-H. (2018). Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(11), 1417-1438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1407352 [ Links ]

Silva Junior, D. I. (2018). Engajamento no trabalho em professores brasileiros (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Salgado de Oliveira do Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Siqueira, M. M. M., Martins, M. C. F., Orengo, V., & Souza, W. S. (2014). Engajamento no trabalho. Em M. M. M. Siqueira (Ed.), Novas Medidas do Comportamento Organizacional - Ferramentas de Diagnóstico e de Gestão (pp. 147-156). Artmed. [ Links ]

Tamayo, M. R., & Tróccoli, B. (2002). Exaustão emocional: Relações com a percepção de suporte organizacional e com as estratégias de coping no trabalho. Estudos de Psicologia, 7(1), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2002000100005 [ Links ]

Tamayo, M. R., Pinheiro, F., Tróccoli, B., & Paz, M. G. T. (2000, 9-14 de julio). Construção e validação da escala de suporte organizacional percebido (ESOP). 52ª Reunião Anual da Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência, Brasília, DF, Brasil. [ Links ]

Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841 [ Links ]

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009 [ Links ]

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141 [ Links ]

van den Heuvel, M., Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2020). How do employees adapt to organizational change? The role of meaning-making and work engagement. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 23(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.55 [ Links ]

van Wingerden, J., Derks D., & Bakker A. B. (2017). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758 [ Links ]

Vogt, K., Hakanen, J. J., Brauchli, R., Jenny, G. J., & Bauer, G. F. (2016). The consequences of job crafting: A three-wave study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 353-362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1072170 [ Links ]

Volpato, G. L. (2007). Bases teóricas para a redação científica. Saipta. [ Links ]

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179-201. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011 [ Links ]

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121-141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121 [ Links ]

Xie, X., Wang, Y., Wang, P., Zhao, F., & Lei, L. (2018). Basic psychological needs satisfaction and fear of missing out: Friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Research, 268(1), 223-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.025 [ Links ]

Data availability: The dataset supporting the results of this study are available at Mendeley Data <https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/d2k42pxzzd/1>.

How to cite: Silva Louro, E., & Gabardo-Martins, L. M. D. (2023). The mediation of work engagement in resource relations with job crafting. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-2867. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2867

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. E. S. L. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; L. M. D. G. M. in a, c, d, e.

Received: March 27, 2022; Accepted: September 21, 2023

text in

text in