Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2023 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3152

Original Articles

Movilidad estudiantil y adultez emergente: Un estudio exploratorio sobre la construcción de identidad en jóvenes universitarios

1 Universidad de la Frontera, Chile

2 Fundación de Desarrollo Educacional para la Innovación Cruzando, Chile

3 Universita Sacro Cuore, Italia

4 Universidad de la Frontera, Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, Chile, leonor.riquelme@ufrontera.cl

5 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

The aim of this research is to comprehend the relation between the student mobility procedures and the identity building of the students of Universidad Católica de Temuco. The methodology delivered in this research was a qualitative methodology following the grounded theory guidelines, considering the international outgoing mobility students. The results pointed out mobility procedures as a landmark that allows the self-knowledge and the construction of an ideal self. This confers the contribution of student mobility in academic and professional aspects as well as the construction of self of the student.

Keywords: internationalization; student mobility; emerging adulthood; professional identity

La presente investigación buscó comprender la relación entre los procesos de movilidad estudiantil y la construcción de la identidad en estudiantes de la Universidad Católica de Temuco. El estudio fue desarrollado a partir de una metodología cualitativa. Se realizaron entrevistas en profundidad a estudiantes que participaron de una movilidad estudiantil internacional saliente. Los resultados demostraron que el proceso de movilidad estudiantil constituye un hito que permite el autoconocimiento y la construcción de un yo ideal. Lo anterior daría cuenta del aporte de la movilidad estudiantil en aspectos académicos, profesionales y en la construcción del yo del estudiante.

Palabras clave: internacionalización; movilidad estudiantil; adultez emergente; identidad profesional

A presente pesquisa buscou compreender a relação entre os processos de mobilidade estudantil e a construção da identidade em estudantes da Universidade Católica de Temuco. A investigação desenvolveu-se a partir de uma metodologia qualitativa. Foram realizadas entrevistas em profundidade com estudantes que realizaram uma mobilidade estudantil internacional de saída. Os resultados revelaram que o processo de mobilidade estudantil constitui um marco que possibilitou o autoconhecimento e a construção de um eu ideal. Isso evidencia a contribuição da mobilidade estudantil em aspectos acadêmicos, profissionais e na construção do eu do estudante.

Palavras-chave: internacionalização; mobilidade estudantil; idade adulta emergente; identidade profissional

University and the construction of professional identity

University entrance is a relevant process in terms of the shaping of young people's identity, where the selection and entry to a particular degree course contributes to this period of self-knowledge. Even so, the meaning they give to their studies is not something totally defined prior to university entrance, but is part of a construction process based on their experiences throughout the process (Guzmán, 2017).

With regard to the exploration of the selected career, the literature has coined the term professional identity, which refers to "a dynamic process through which the subject defines him/herself in relation to a workspace and a professional reference group or collective" (Balduzzi & Egle, 2010, p.67). This concept implies the construction of an identity based on a cultural context of interaction that enables the integration of patterns and behaviours specific to the professional environment, establishing a construction of oneself based not only on the work, but also as a means of defining who one is (Mulone, 2016).

Indeed, Bolívar et al. (2005) consider that professional identity is a dimension that stems from the concept of identity, which cannot be constructed without another as a reference within a space of common interaction between the social environment and the professional environment. This conception is in line with Evetts (2003), who incorporates common experiences as a modelling element of professional identity. Accordingly, one of the processes that supports the construction of the individual and professional identity of university students based on experience is that of student mobility within a context of globalization, improving their academic training and cultural perception (Corbella & Elías, 2018).

Student mobility

Student mobility is one of the expressions of internationalization in education as a political market process and as a way of thinking globally about academia (Corti et al., 2015), as well as being the most visible branch of university internationalization (Lloyd, 2016) and making a significant contribution to narrowing the gaps between students from different socio-economic backgrounds (Pogodzinski et al., 2021).

Although there is no consensus on the exact definition of the term student mobility, according to Corbella and Elías (2018), a century ago, student mobility was a spontaneous process linked more to personal motivations and possibilities than to projects linked to institutional strategies (Ibarra, 2016). Nowadays, this responds to institutional strategies that are visualised in different public policies with the aim of attracting students. In this sense, countries such as the United States, China and India are positioned as the main countries that promote international student mobility (Lloyd, 2016).

Mobility students are generally outstanding students who have passed a selection process and are looking for new experiences (Guzmán, 2017). In this sense, for Guzmán (2017), the interest in the studies of students who manage to adapt to the new context sometimes takes a back seat, and their interest is focused more on the experiences they have had.

The need for professionals prepared for diversity and adversity is necessary to meet the needs and interests of citizens in different areas of society. This is why student mobility enriches, in different ways, the capacities of future professionals (Vaicekauskas et al., 2013).

In this context, student mobility allows not only the generation of internationally oriented professionals, but also the acquisition of competences that enable better integration into the world of work and the generation of cultural ties (Vaicekauskas et al., 2013). As a result of the above, Resnik (2012) argues that internationalisation processes generate professionals with international orientations and that they affect not only the future professional, but also those who are not participants in the student mobility processes.

The motivations linked to the decision to undertake a mobility process can have different meanings (Otero et al., 2019). For example, a concordance can be observed between mobility and an improvement in teamwork (Rienties et al., 2013), as well as cultural enrichment as a result of new experiences on both a personal and academic level (Otero et al., 2019). Furthermore, there is a relationship between aspirations for social mobility through student mobility (Findlay et al., 2011) and a correlation between capital and mobility processes, which is evidence of relations of inequality (Bilecen & Van Mol, 2017).

While previous research addresses different aspects of the impacts and motivations linked to student mobility processes, it does not address how it articulates with the construction of the self within the student's life cycle and how student mobility can foster selective processes that reaffirm identity.

In this context, Universidad Catolica de Temuco is located in the capital of the Araucanía region, a region with a high percentage of indigenous population, receiving students from communes close to the regional capital. To date, the university has more than 300 students who have undertaken outgoing student mobility, distributed in more than 20 countries, the main ones being Brazil, Colombia, France, Spain and Mexico. In this sense, the university already has experience in mobilisation processes, but even so, the systematisation of the information has had a management focus. The present research aims to understand the relationship between student mobility processes and the construction of identity in students at Universidad Católica de Temuco.

Method

Design

The research was developed under a qualitative methodology (Valles, 2007) and a descriptive non-experimental cross-sectional design (Cea D'Ancona, 1996) based on the characteristics of grounded theory for the generation of knowledge, increasing the understanding of reality, orientation for action and fostering the creativity of researchers (Strauss & Corbin, 2002).

Participants

The selection process of the participants was based on a theoretical sampling that allowed the selection of cases according to the progress and need of the research (Glaser & Strauss, 1976). The inclusion criteria considered students of Universidad Catolica de Temuco within the last 5 years (2014-2019), without considering the pandemic period, who had completed their international mobility process. As a result of the above, the participants who carried out mobility were students from the Faculty of Architecture, Art and Design; Faculty of Health Sciences; Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities; Faculty of Legal, Economic and Administrative Sciences; Faculty of Engineering; Faculty of Education and the Faculty of Natural Resources. This allowed for a total of 10 students, 6 of whom were female and 4 male, with an average age of 25.2 years (SD= 1.87), with a median and mode of 25 years. Similarly, the countries in which they did their student mobility internships were Germany, Colombia, Spain, Mexico and the United Kingdom.

Instrument

In-depth interviews were applied based on the intention that the students would reflect on themselves and how their experience was linked to the construction of their own identity. This is in line with the methodological postulates indicated by Martuccelli and de Singly (2012), who stated that the interview allows for work on oneself, generating a reflective process in terms of their interactions and how the reasons for their actions can be established within contradictions in the face of the multiplicity of scenarios. Similarly, the in-depth interview is compatible with an analysis aimed at inductively investigating the subject's perceptions and social evaluations within a given historical context (Finkel et al., 2008), as it is dialogical and spontaneous, while marking a variable intensity (Gaínza, 2006).

Procedures

An email was sent to the institutional accounts of the students who met the requirements according to the database of the International Relations Department of Universidad Catolica de Temuco. In the email, the objective of the research was indicated and an informed consent form was sent. If the student approved their participation, they were asked to send the informed consent form with their digital signature. Once the students had been contacted, an interview was conducted through digital platforms, indicating, before the interview began, the objective of the research and the ethical safeguards, and requesting permission to record only the audio of the interview. Once the conditions were accepted by the student, the interview proceeded. The interview guideline established general topics so as not to delimit or direct the interview in depth, but rather to give way to the scenarios that the student considered relevant (Finkel et al., 2008).

Ethical considerations

Individual information was safeguarded by the signing of informed consents by the students, with a copy of the consent form being kept by the research team and another copy by the student. The informed consent stated that, during the course of the interview, the interviewee could withdraw at any time he/she deemed appropriate. With regard to the above, it was indicated that the information collected would not be published in such a way that the individual identification of the student would be exposed.

Information processing

The processing of the information collected was carried out through the assumptions of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 2002), but from a constructivist approach that questions the initial objective bases (Charmaz, 2006) from the comparative strategy, which allows, simultaneously, the process of collecting information, coding and data analysis (Bonilla-García & López-Suárez, 2016). In view of this, the comparative method allows the research to be directed by the results that emerge, influencing the following interviews, the questions, the sampling and the formation of categories.

As the interviews were conducted, the audios were analysed using the Atlas TI. version 6.2 software, as this is coupled to the coding processes demanded by grounded theory through the steps of open and axial coding (San Martín, 2014). To do this, we proceeded to generate open quotations, and then coded according to the emerging themes in order to finally establish the relationships between the categories and the creation of semantic networks.

Finally, there are methods that make the researcher's influence on the analysis process transparent. One of them refers to the processing of information by more than one researcher in order to compare perceptions of the analysis (Gibbs, 2007). Similarly, the results can be shared with the interviewees themselves in order to receive feedback on the interpretation of the interviews (Gibbs, 2007). In the specific case of this study, the analysis was triangulated by three researchers. In addition, the results were sent to the interviewees for review and subsequent feedback, from which the corresponding adjustments were made to the specification of the codes and the interpretation.

Results

Motivations for international student mobility

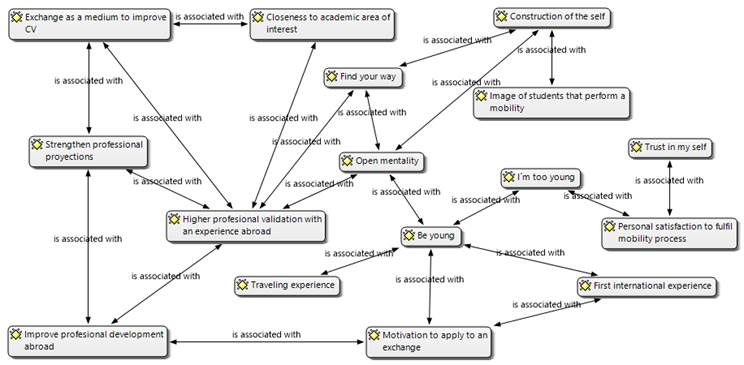

The first category refers to the characterization of students' motivations for applying for and undertaking international student mobility.

Figure 1 shows blocks related to the experience of being a young person with academic duties. In this sense, those motivations linked to the generation of curricula with a view to professional performance and integration into the world of work are represented. As a result of the above, one student argues:

In order to build a CV, in Chile, unfortunately, you are stigmatised by what you have on your CV. If you show that you have an internship in Spain, unfortunately, you are seen more highly by others. That was, on the one hand, and on the other, because I saw that veterinary medicine in Spain is very advanced (Interview 1(7)).

The search for knowledge specific to the degree course studied is mixed with interests specific to the stage of the life cycle in which the student is positioned, where experience functions as an important motivator. As a result of the above, one student expresses the following:

There were three motivations. The first was to get to know another country, another culture. The second was to relate professionally with colleagues from other countries, because at least in the city I went to, Medellín, there were 174 exchange students from different countries. So generating those ties, so far, has been enriching. And the third motivation was to be able to travel within the country (Interview 5(4)).

The students' motivations are positioned on the basis of experience. Even in the case of the academic link, the experiences are more relevant than the more theoretical aspects of the training process within the mobility. The above is consistent with what is expressed by the student, who indicates:

I think that there was not so much a question of knowledge or theory at study level. But it was a question of how I communicate with my professors and career directors. Because over there, it was very much the case that people dealt with the teachers or the older people as you and you, not like here, where you deal with them as you. So it was a more linear relationship, yes of respect, but not as separate as it is here (Interview 8(17)).

In the relationship between being young and the process of student mobility, there is an association with the experience of travelling, not only as a process of getting to know, but also as a way of constructing the desired self. In this context, the image of the students who spend time abroad, prior to their own experience, was represented as curious and adventurous people, able to cope with the uncertainty produced by the unknown. This is seen as a relationship between the imaginary of the mobility student and the student him/herself, establishing a reaffirmation or reconstruction of the self in terms of distance from the mobility student model. This is established as a channelling of who I am and who I want to be as a way of materialising in actions that allow the distance between the self and the mobility student model to be shortened. As a result of the above, one student refers:

I had always kind of heard, I had always been attracted by the topic of exchange. But I never imagined myself doing an exchange, as I saw it as very distant, as I saw myself as very young, as I must confess that I have always seen myself, I had always seen these profiles of people who are very adventurous, as if they are not afraid of anything and go out into the world, and I am more fearful, that is, I would not say I am a coward, but I am more structured (Interview 9(5)).

When referring to “being a boy”, it is not established as a desired characteristic, but as something necessary to overcome through the acquisition of new experiences that allow the level of uncertainty and doubts, both personal and vocational, to be reduced. In this sense, someone who is young could be someone who is not able to deal with his or her levels of uncertainty individually, establishing a static state of non-action under the questions that arise in pursuit of a personal and professional future. This is rooted in how the student seeks to acquire experiences that enable him/her to deal with the above, which is linked to the mobility student model, i.e. under someone who takes charge of his/her own self. The above, can be observed in the account of one student, who indicates:

I think I matured a lot, having to live on my own, that there is no one behind me telling me you studied, make your bed, wash the dishes. Firstly, having the experience of having lived independently with my other partner, but taking care of our place, making sure it is clean and looked after. On the other hand, to worry about studying, revising the material (Interview 4 (22)).

Therefore, the search for the path refers to the search and insistence on knowing and experiencing both personally and professionally according to personal interests. This suggests that there is no search for personal interests without an exploration, which is coupled with the identity creation processes of young people, whether in a personal or collective identity and how this validates or reconstructs the individual and professional self.

Personal satisfaction regarding the mobility process is extrapolated into confidence in the student himself regarding overcoming mobility in terms of personal challenge. This challenge is not only established in academic terms, but in how the student adapts, overcomes and integrates in a context other than everyday life. This again denotes the exploration regarding the experience in the construction and reaffirmation of the self as a feedback from the environment in terms of expectations. F2

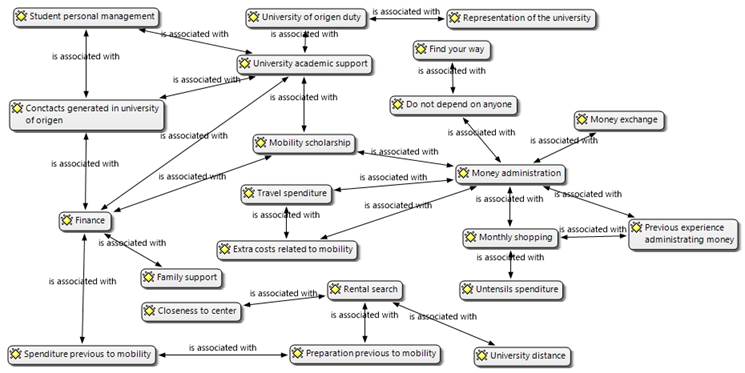

Money management

Money management is positioned as an important emerging element of students' resource management. Many of the students had to be able to manage the resources provided by the scholarship and family support, establishing an income planning either on a monthly or weekly basis. This was most noticeable in those students who received less support from third parties. Money management is an essential element in the daily life of the students, as it is established as a means that makes it possible to participate in extracurricular activities, unforeseen expenses, travel, and initial expenses for the place of residence, among others. A student expresses her first approach to managing finances:

I think that what affected me the most is my independence, I was able to value my independence a lot and now I want it back. Of course, because in the end I was responsible for myself, for all the actions I did, I had to manage how to spend my money or how much money I could spend. So, in the end, I ended up being more organised, to know how much time I have to plan my activities. So, in the end, it helped me to organise my professional life and also my non-professional life, my private life (Interview 7(14)).

Money management is expressed as a symptom of managing uncertainty, as a way of daily life, both in professional and private life. On the other hand, money management and its effectiveness also respond to previous experiences, for example, of students who, for academic purposes, migrated from their usual residences to areas close to the university or who had already entered the field of work:

I've always worked, like since I was 14, so I've always had my own money and I've always known how to have my savings account. I'm much organised about it, at least which was an advantage, because I always had my own money and I knew how to manage it. We were able to manage our money in such a way that we could afford to travel. Having had previous experience with money was a plus in having that money because it's still a lot of money and you have responsibilities to fulfil (Interview 4(31)).

Previous experience in money management is an important element in the process of adapting to everyday life during the stay in the destination country. This is linked to previous experiences in Chile with regard to the need to rent independently in the vicinity of the university. This allows this group of students to know what utensils, food and household products to buy. In other words, how to manage the money they had at their disposal. On the other hand, part of their interest in the use of money was focused on the generation of experiences specific to the life cycle in which they find themselves, i.e. exploring the country of mobility:

I carried savings and in the end, our savings, I think that we, with the girls we hung out with, I think we were one of the ones who travelled the most of the mobility students within the country and managing the money we travelled a lot (Interview 10(22)).

Finally, the main sources of funding are linked to the scholarship granted by the university, as well as the contribution of family members and the economic resources managed by the student within the university. With regard to the latter, both the scholarship and the extra help from the university are perceived as a duty, since the student is positioned as a representative of the higher education institution. Under this, one student expresses:

From my point of view, the minimum that you get something back, apart from that, you are going to wear the coat of arms of your university for your whole life, that's why I didn't even feel ashamed to make a lot of letters to ask and the resources are there, I took out resources (Interview 1(15)).

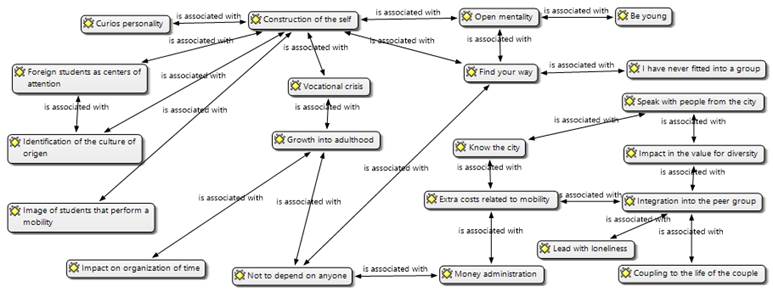

Building who I am

Semantic network 3 (Figure 3) focuses on the processes of constructing the self and how student mobility contributes within complex periods of vocational and personal crisis and on the verge of entering the world of work.

Students are in a transition period as they are in the middle of their degree course. It should be remembered that mobility students at the Universidad Católica de Temuco can only carry out their exchange program from the third year onwards. As a result of the above, this crisis is evident in the following interviewee's account:

In third year I had a crisis, like a vocational crisis, as it happens to everyone. But I said, now, what am I going to do with my career, with my future, do I like what I'm going to do with my career? I don't know if it happens to everyone, but I've heard a lot of people say that it's a transition process. I mean, I entered the career very young, I felt like I was still in high school, so I spent the whole summer of 2018, trying to see what I wanted, like I was taking a step from adolescence, I don't know if it was to adulthood, I don't think so, but already as a young professional, a future close to being a professional (Interview 9(7)).

Doubts regarding the career, arise in a period of uncertainty and construction of the students' future. In this respect, the mobility process is accompanied by a cycle of major changes and questioning of future activities on the part of the student. In this sense, student mobility can present contradictory characteristics, i.e., taking on an activity, such as student mobility, can bring with it a high level of uncertainty, but indeed, this aspect can contribute to reducing uncertainty regarding the construction of who I am and who I want to be.

In this sense, the construction of people with a higher level of autonomy and management of uncertainty is seen as something desired and valued, during and after the mobility process. This is observed in the words of the following student:

I became like more uninhibited or more... how can you say, it gave me like more security. It's like a security for surviving. As there was information that I didn't know, I needed to get it and there was nobody, so I had to, by obligation I had to approach people or professionals to get help (Interview 6(15)).

The search for experiences is seen as an essential action, both in how they face their integration within the destination country, as well as in academic aspects. In this sense, integration into the peer group is presented as a relevant action not only in an academic environment, but also as a means to combat loneliness in an uncertain and unknown context. As a result of this, one student states:

They helped me a lot, a lot. They gave me company, they knew I was alone at home and they said to me, what are you doing alone there? And I told them, nothing. And then they started to invite me to stay at their house on weekends, we went to the cinema, we went to the amusement park, they invited me to family dinners, so it was a very strong and very nice bond (Interview 2(14)).

On the other hand, the students identified aspects of their culture of origin, among these, the accent, which identified them as foreigners. As a result of this, one student states:

In the degree course we were on, there were three of us on exchange, and we would talk and they would stare at us, because our accent is different. I thought that Chileans didn't have an accent, but it was the most noticeable in all of Latin America and the professors made us read, I don't know if it was to laugh or to listen to us, but yes, we were the novelty for a long time (Interview 10(12)).

In turn, the identification of the culture of origin by the peer group establishes a stereotype of the personality, skills and behaviours of mobility students. In the construction of identity, young people share their experiences as a projection and externalisation of their reality as a way of presenting who they are in a collective self, members of a cultural system and a history. As a result of the above, one student indicates:

One was equally puffed up talking about their country and they were very interested in knowing the situations since the dictatorship, it was a very very important topic that they were interested in. The Mapuche conflict was also a very important topic for them. How I experienced the 2010 earthquake, how I reacted with the same volcano that I told them we had, and that makes you feel bigger, because you talk about something that is yours (Interview 2 (18)).

Discussion

This research sought to understand the relationship between the processes of student mobility and the construction of identity in students at Universidad Catolica de Temuco. In this context, the data shows an ambivalent period between who I am and who I want to be, which is consistent with Arnett (2000), who states that emerging adulthood is a stage where the exploration of identity is central and in which elements of adolescence and adulthood are experienced.

In this sense, the process of student mobility follows the logics of the new student, that is, it is an experience where elements of youth are experienced; but, at the same time, with academic responsibilities (Dubet, 2005). Under the above, although mobility is not the central element in the process of identity construction of young people, it is established as an instance of awareness of the self, that is, different experiences are generated that allow reflection on belonging within a collective history and how young people project themselves in a country other than their country of origin, which sheds light on the importance of the social environment to rethink identity (Araujo & Martuccelli, 2012; Berger & Luckmann, 2003).

The results show an ideal type of student, who is positioned as a person capable of coping on their own with the uncertainty involved in adapting to a new context. This is consistent with the results presented by Barrera and Vinet (2017) in the framework of Chilean university students, who distinguish three general aspects with respect to Arnett's (2000) theory. Of these, they highlight self-regulation and knowledge of economic and academic factors.

The process of international mobilisation is positioned as a rite in a moment of vocational crisis on the verge of graduating from the chosen career. In this sense, Guzmán (2017) indicates that the meaning given to the career is part of a construction of experiences, and therefore, when students indicate their motivations for applying, the academic and non-academic experiences, as well as the experiences, are positioned as relevant elements in their discourses.

Together with the above, the search for greater professional experience, linked to the development of the professional trajectory, would operate to decipher the professional they wish to be through interaction with other professionals, the integration of guidelines of the professional culture (Bolívar et al., 2005; Evetts, 2003; Mulone, 2016) and the generation of a greater curriculum.

An emerging element of interest refers to the management of money as an indispensable resource to be able to channel their stay in a destination country. In this sense, Quintano and Denegri (2021) indicate that money establishes a symbolic representation that contributes to the construction in young people of who they want to be, as it becomes a facilitator for integration into the peer group. Along the same lines, Zelizer (2011) indicates that money not only has an abstract sense of transaction, but also makes it possible to manage situations of uncertainty and control individual or group identity, among other social meanings. According to Zelizer (2011), the administration of money would account for an action of uncertainty management in the participants, where its administration would make it possible to manage daily life, but at the same time, it would be a means to integrate into activities organised by peers or to travel around the country.

In short, the results show the contribution of student mobility not only in evaluative aspects of the mobility process, but also about the relationship established with the construction of identity and exploration as a result of new experiences (Otero et al., 2019), as central elements in the stage of emerging adulthood, on the basis of students facing a dichotomous scenario, i.e., where they must assume academic responsibilities and be young.

Similarly, student mobility would account for contradictory characteristics where taking on uncertainty would, in effect, allow for autonomous ways to diminish it, contributing to greater self-knowledge and less distance between who I am and who I want to be.

As a limitation of the present research, the need arises to address in subsequent studies, a research process that delves deeper into the categories outlined above and, with this, expands the variability of students in other contexts in order to compare and observe whether the link between the process of student mobilisation and emerging adulthood form precisely a cross-cutting stage or only applies to this specific group. A limitation of the above is the impossibility of extrapolating the results presented here, since emerging adulthood, being a social stage, is not expressed as a cross-cutting process. Despite this, our research provides important inputs for understanding the rituals linked to a stage of transition and exploration of young people who experience student mobility.

REFERENCES

Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2006). Visión panorámica de la internacionalización en la educación superior: Motivaciones y realidades. Perfiles Educativos, 28(112), 13-39. [ Links ]

Amendola, A., & Restaino, M. (2016). An evaluation study on students’ international mobility experience. Quality & Quantity, 51(2), 525-544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0421-3 [ Links ]

Araujo, K., & Martuccelli, D. (2012). Desafíos comunes. Retrato de la sociedad chilena y sus individuos (Tomo I). LOM. [ Links ]

Arnett, J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469 [ Links ]

Balduzzi, M., & Egle, R. (2010). Representaciones sociales e ideología en la construcción de la identidad profesional de estudiantes universitarios avanzados. Revista Intercontinental de Psicología y Educación, 12(2), 65-83. [ Links ]

Barrera, A., & Vinet, E. (2017). Adultez emergente y características culturales de la etapa en universitarios chilenos. Terapia Psicológica, 35(1), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48082017000100005 [ Links ]

Barrera, A., Vinet, E., & Ortiz, M. (2020). Evaluación de la adultez emergente en Chile: validación del IDEA-extendido en universitarios chilenos. Terapia Psicológica, 38(1), 47-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082020000100047 [ Links ]

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (2003). La construcción social de la realidad. Amorrortu. [ Links ]

Bilecen, B., & Van Mol, C. (2017). Introduction: international academic mobility and inequalities. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(8), 1241-1255. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300225 [ Links ]

Bolívar, A., Fernández, M., & Molina, E. (2005). Investigar la identidad profesional del profesorado: Una triangulación secuencial. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.1.516 [ Links ]

Bonilla-García, M., & López-Suárez, A. (2016). Ejemplificación del proceso metodológico de la teoría fundamentada. Cinta de Moebio, (57), 305-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-554X2016000300006 [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (2009). Los herederos. Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Bustos-Aguirre, M. (2022). ¿Por qué algunos estudiantes realizan movilidad internacional y otros no? Sociologías, 24(61), 290-321. https://doi.org/10.1590/18070337-121922 [ Links ]

Cea D’Ancona, M. (1996). Metodología Cuantitativa. Estrategias y técnicas de investigación social. Síntesis. [ Links ]

Chao, R. Y. (2020). Intra‐ASEAN student mobility: overview, challenges and opportunities. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/jarhe-07-2019-0178 [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Educación. (2021). Índices de Educación Superior. https://www.cned.cl/indices-educacion-superior [ Links ]

Corbella, V., & Elías, S. (2018). Movilidad estudiantil universitaria ¿qué factores inciden en la decisión de elegir Argentina como destino? Perfiles Educativos, 40(160), 120-140. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2018.160.58399 [ Links ]

Correa, P. S., Mola, D. J., & Reyna, C. (2020). Efecto de la disponibilidad de recursos económicos sobre funciones cognitivas y preferencias sociales. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(1), e-2080. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2080 [ Links ]

Corti, A., Oliva, D., & de la Cruz, S. (2015). La internacionalización y el mercado universitario. Revista de la Educación Superior, 44(2), 47-60. [ Links ]

Dubet, F. (2005). Los estudiantes. CPU-e, Revista de Investigación Educativa, 1, 1-78. https://doi.org/10.25009/cpue.v0i1.148 [ Links ]

Erikson, E. (1985). El ciclo vital completado. Paidós. [ Links ]

Evetts, J. (2003). Identidad, diversidad y segmentación profesional: el caso de la ingeniería. En M. Sánchez-Martínez, J. Sáez & L. Svensson (Coords.), Sociología de las profesiones. Pasado, presente y futuro (pp. 141-154). Diego Marín Librero. [ Links ]

Findlay, A., King, R., Smith, F., Geddes, A., & Skeldon, R. (2011). World class? An investigation of globalisation, difference and international student mobility. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 37(1), 118-131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00454.x [ Links ]

Finkel, L., Parra, P., & Baer, A. (2008). La entrevista abierta en investigación social: trayectorias profesionales de ex deportistas de élite. En A. Gordo & A. Serrano (Coord.), Estrategias y prácticas cualitativas de investigación social (pp. 127-154). Pearson-Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Gacel-Ávila, J. (2018). Internacionalización comprehensiva en América Latina y el Caribe. https://eulacfoundation.org/es/system/files/Internacionalización%20comprehensiva%20ALC.pdf [ Links ]

Gaínza, Á. (2006). La entrevista en profundidad individual. En M. Canales (Ed.), Metodologías de investigación social: Introducción a los oficios (pp. 219-263). LOM. [ Links ]

Gerhards, J., & Hans, S. (2013). Transnational Human Capital, Education, and Social Inequality. Analyses of International Student Exchange. Zeitschriftfür Soziologie, 42(2), 99-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2013-0203 [ Links ]

Gibbs, G. (2007). El análisis de datos cualitativos en Investigación Cualitativa. Morata. [ Links ]

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of Grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. [ Links ]

Guzmán, C. (2017). Las nuevas figuras estudiantiles y los múltiples sentidos de los estudios universitarios. Revista de la Educación Superior, 46(182), 71-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resu.2017.03.002 [ Links ]

Ibarra, B. (2016). Patlani, un instrumento estadístico de la movilidad estudiantil en México. Revista de la Educación Superior, 45(180), 113-119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resu.2016.10.001 [ Links ]

Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization remodeled definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1028315303260832 [ Links ]

Kumpikaitė, V., & Duoba, K. (2011). Development of intercultural competencies by student mobility. The Journal of Knowledge Economy & Knowledge Management, 6(4), 41-50. [ Links ]

Lloyd, M. (2016). ¿El gran negocio de la internacionalización de la educación superior? Campus Milenio, (680), 34-35. [ Links ]

Martuccelli, D., & de Singly, F. (2012). Las sociologías del individuo. LOM. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación (2021, 8 de junio). Matrícula de educación superior aumenta en 2021: total supera 1.200.000 estudiantes. https://acortar.link/kljcsj [ Links ]

Mulone, M. (2016). El proceso de construcción de la identidad profesional de los traductores de inglés. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 17(19), 152-166.https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2016.19.192 [ Links ]

Otero, M., Giraldo, W., & Sánchez, J. (2019). La movilidad académica internacional: experiencias de los estudiantes en Instituciones de Educación Superior de Colombia y México. Revista de la Educación Superior, 48(190), 71-92. https://doi.org/10.36857/resu.2019.190.712 [ Links ]

Petzold, K., & Moog, P. (2017). What shapes the intention to study abroad? An experimental approach. Higher Education, 75(1), 35-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0119-z [ Links ]

Pogodzinski, B., Cook, W., Lenhoff, S. W., & Singer, J. (2021). School climate and student mobility. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 21(4), 984-1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2021.1901121 [ Links ]

Pozo, J., & Rojo, E. (2003). Movilidad estudiantil, integración y convergencia. Calidad en la Educación, (19), 143-149.https://doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n19.367 [ Links ]

Quintano, F., & Denegri, M. (2021). Actitudes hacia el endeudamiento en estudiantes secundarios chilenos. Suma Psicológica, 28(2), 79-87. https://doi.org/10.14349/sumapsi.2021.v28.n2.2 [ Links ]

Resnik, J. (2012). The Denationalization of Education and the Expansion of the International Baccalaureate. Comparative Education Review, 56(2), 248-269. https://doi.org/10.1086/661770 [ Links ]

Rienties, B., Hernández, N., Jindal, D., & Alcott, Peter. (2013). The role of cultural background and team divisions in developing social learning relations in the classroom. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(4), 322-353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1028315312463826 [ Links ]

Rivera, D., Cruz, C., & Muñoz, C. (2011). Satisfacción en las relaciones de pareja en la adultez emergente: el rol del apego, la intimidad y la depresión. Terapia Psicológica, 29(1), 77-83. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48082011000100008 [ Links ]

San Martín, D. (2014). Teoría fundamentada y Atlas.ti: recursos metodológicos para la investigación educativa. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 16(1), 104-122. [ Links ]

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Universidad de Antioquía. [ Links ]

Suárez, M. (2018). Génesis de la juventud de los estudiantes universitarios. Perfiles Educativos, 11(159), 177-191. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2018.159.57971 [ Links ]

Taylor, C. (1996). Identidad y Reconocimiento. Revista Internacional de Filosofía Política, (7), 10-19. [ Links ]

Tokas, S., Sharma, A., Mishra, R., & Yadav, R. (2023). Non-economic motivations behind international student mobility: An interdisciplinary perspective. Journal of International Students, 13(2), 155-171. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v13i2.4577 [ Links ]

Torche, F., & Wormald, G. (2004). Estratificación y movilidad social en Chile: entre la adscripción y el logro. CEPAL. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/544893?ln=es [ Links ]

Vaicekauskas, T., Duoba, K. & Humpikateite-Valiuniene, V. (2013). The role of international mobility in students core competences development. Economics and Management, 18(4), 847-856. http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.em.18.4.5686 [ Links ]

Valles, M. (2009). Técnicas cualitativas de investigación social: Reflexiones metodológicas y práctica profesional. Síntesis. [ Links ]

Verbik, L., & Lasanowski, V. (2007). International Student Mobility: Patterns and Trends. Observatory of Borderless Higher Education. [ Links ]

Webb, G. (2005). Internationalisation of curriculum: an institutional approach. En J. Carroll & J. Ryan (Eds.) Teaching International Students, Improving Learning for All (pp. 631-648). Routledge. [ Links ]

Zelizer, V. (2011). El significado social del dinero. Fondo de Cultura Económica [ Links ]

How to cite: Quintano-Méndez, F., Brandt, J., Latorre, P., Riquelme-Segura, L., & Zapata, M. (2023). Student mobility and emerging adulthood: exploratory research about identity building in young university students. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-3152. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3152

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. F. Q. M. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; J. B. in b, c, d; P. L. in c, d, e; L. R. S. in a, d, e; M. Z. in a, d, e.

Received: December 21, 2022; Accepted: September 28, 2023

texto en

texto en