Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Ciencias Psicológicas

Print version ISSN 1688-4094On-line version ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.1 Montevideo 2023 Epub June 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2695

Original Articles

The effects of the Promove-Casais program on conjugality, parenting, mental health, and child behavior

1 Psicologia Lima e Ferraz LTDA, Brazil, bolsoni.silva@unesp.br

2 Universidade Estadual Paulista, Brazil

This study describes the effects of the Promove-Casais program on marital relationships, parenting, child behavior, and mental health. Nine couples were randomly assigned to two groups: five to the experimental group (EG) and four to the control group (CG). The participants completed the instruments measuring this study’s variables of interest. The results indicate the intervention was effective because, after the intervention, the experimental group more frequently experienced positive relationships (improved communication, affection, and self-control), positive parent-child interactions, and improved marital satisfaction and children’s social skills, while negative marital relationships, negative parent-child interactions, and problem behaviors subsided; these results remained in the follow-up. On the other hand, the CG experienced no such changes. The conclusion is that Promove-Casais can be implemented to prevent and remediate interactional problems within the family, promoting improved quality of life and mental health.

Keywords: marital relationship; parent-child relationships; mental health; social skills; behavior problems; Behavioral Analytic Therapy.

Este estudo teve por objetivo descrever os efeitos do Promove-Casais, para o relacionamento conjugal, parentalidade, comportamentos infantis e saúde mental. Participaram do estudo cinco casais no grupo experimental (GE) e quatro no grupo controle (GC), que foram aleatoriamente distribuídos. Os participantes responderam a instrumentos sobre as variáveis de interesse do estudo. Os resultados permitiram afirmar sobre a efetividade da intervenção pois o relacionamento positivo (comunicação, afeto, autocontrole), a satisfação conjugal, as interações positivas pais-filhos e as habilidades sociais infantis melhoraram após a intervenção no GE, bem como o relacionamento conjugal negativo, as interações negativas pais-filhos e os problemas de comportamento reduziram após a intervenção. Estes resultados se mantiveram nas avaliações de seguimento. No GC não se verificaram alterações. Conclui-se que o Promove-Casais é um programa que pode ser aplicado na prevenção e na remediação de problemas interacionais no âmbito familiar, promovendo melhor qualidade de vida e saúde mental.

Palavras-chave: relacionamento conjugal; relacionamento parental; saúde mental; habilidades sociais; problemas de comportamento; terapia analítico comportamental

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo describir los efectos del programa Promove-Casais para la relación matrimonial, la paternidad, el comportamiento de los niños y la salud mental. Cinco parejas participaron en el estudio en el grupo experimental (EG) y cuatro en el grupo de control (CG), los que fueron distribuidos aleatoriamente. Los participantes respondieron a los instrumentos sobre las variables de interés en el estudio. Los resultados permiten afirmar la efectividad de la intervención al encontrarse que la relación positiva (comunicación, afecto, autocontrol), la satisfacción conyugal, las interacciones positivas entre padres e hijos y las habilidades sociales de los niños mejoraron después de la intervención en el EG. Además, la relación conyugal negativa, las interacciones negativas entre padres e hijos y los problemas de comportamiento se redujeron después de la intervención. Estos resultados se mantuvieron en las evaluaciones de acompañamiento. No hubo cambios en el CG. Se concluyó que el Promove-Casais es un programa que mejora la calidad de vida y salud mental y que puede ser aplicado en la prevención y la reconciliación de problemas de interacción dentro de la familia.

Palabras clave: relacionamiento conyugal; relacionamiento parental; salud mental; habilidades sociales; problemas de comportamiento; terapia analítica comportamental

Studying conjugality is relevant because marital relationships are complex and marital conflicts can harm the mental health of couples (Durães et al., 2020) and children (Mark & Pike, 2017). Multiple factors may interfere with a marital relationship and marital satisfaction, including sociodemographic variables (Durães et al., 2020; Rady et al., 2021), financial situation (Wagner et al., 2019), parenting (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017), child behavior (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Mark & Pike, 2017) and mental health (Choi & Jung, 2021; Hsiao, 2017). Evidence shows that the quality of positive communication, the low occurrence of negative communication, positive affect, and problem-solving strategies contribute to the quality of marital relationships and marital satisfaction (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Kazim & Rafique, 2021). Some studies exemplifying such relationships are presented here.

In a study review assessing the predictors of marital satisfaction in individualistic and collectivistic cultures, Kazim and Rafique (2021) found that romantic love, intimacy, interpersonal communication, emotional intelligence, conflict resolution, expectations regarding the relationship, trust, commitment, autonomy, gratitude, shared leisure time, and social support are elements universally required for marital satisfaction. Wagner et al. (2019) addressed 750 Brazilian men and 750 women to identify how problem-solving styles influenced the quality of marital relationships. They found that constructive ways to solve problems and strategies to deal with financial problems and house chores, in addition to the time couples spend together, predicted good quality of marital relationships. Women tend to report marital dissatisfaction more frequently than men (Durães et al., 2020; Rady et al., 2021).

Additionally, the arrival of a child demands couples to adapt to new tasks. Hence, the higher the number of children, the more conflicts and the greater the level of anxiety and dissatisfaction; though, it is also an opportunity to develop responsibility and teamwork (Durães et al., 2020). Furthermore, such conflicts may increase the risk of negative practices, which influence the occurrence of problem behavior (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017).

Hosokawa and Katsura (2017) analyzed the reports of 2,931 Japanese mothers of 5 and 6-year-old children, focusing on the relationships between marital communication, parenting, and child behavior. They verified that marital conflicts and negative parenting practices were directly associated, resulting in children’s low scores on social skills. Moreover, negative practices mediated the relationship between parental conflict, cooperation behavior, and children’s self-control. On the other hand, constructive marital relationships were positively associated with positive practices and self-control. The authors above concluded that destructive and constructive marital conflicts influence children’s social skills development by mediating parental practices.

Similar results are reported by Bolsoni-Silva and Loureiro (2020a), in which a case-control design was adopted to address a sample of mothers (35 mothers with depression and 35 without depression) of young Brazilian children. Depression was found to be associated with marital relationship and parenting. Positive practices were directly associated with children’s social skills, while negative practices were associated with problem behavior. Additionally, linear regression showed that depression, a deficit in positive marital relationships and marital satisfaction, and excessive marital conflicts influenced externalizing problems. Furthermore, children with internalizing and externalizing problems presented fewer social skills, lived in families with more marital problems, negative practices, and maternal depression, and with fewer positive marital relationships and less frequent positive parenting.

Choi and Jung (2021) found an association between marital satisfaction and depressive symptoms among 1,264 Korean couples with young children. The couples reported satisfaction and depression at three points in time over four years. No differences were found between genders, but the results showed direct relationships between marital problems and depression. The authors above suggest couple counseling to screen depressive symptoms in both partners along with existing marital problems.

Vafaeenejad et al. (2018) conducted a systematic literature review and found that depression and parental stress might harm a marital relationship, while depression and parental anxiety increased the likelihood of negative parenting and child maltreatment. Hence, evidence shows that marital conflicts might favor depression and negative parenting, whereas depression may increase the likelihood of marital conflicts and negative parenting styles.

Bolsoni-Silva and Loureiro (2019) addressed a sample of 151 Brazilian biological mothers and verified that positive parenting and an excess of negative practices differentiated the groups in terms of marital relationship directly related to parenting; low scores were obtained in consistency, positive communication, and negotiation, specifically listening to others’ opinions, changing behavior, agreeing with parental practices, and apologizing. Greenlee et al. (2022) conducted a longitudinal study with 188 parents of children with autism. They verified that the couples experienced conflicts and dissatisfaction because they disagreed on how to deal with their children’s behaviors.

In summary, there are various relationships between the variables previously mentioned: (a) harmonious marital relationship and children’s social skills (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017; Mark & Pike, 2017); (b) positive practices directly related to children’s social skills (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019; Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017); (c) problem behavior and an excess of negative practices (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019; Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Greenlee et al., 2022; Vafaeenejad et al., 2018); (d) problem behavior and marital problems (Greenlee et al., 2022; Mark & Pike, 2017; Tomfohr-Madsen et al., 2020); (f) maternal depression and increased likelihood of negative practices (Vafaeenejad et al., 2018; Zalewski et al., 2017); (g) depression affecting marital relationships (Vafaeenejad et al., 2018); and (h) marital dissatisfaction influencing couples’ (Rathgeber et al., 2019) and children’s mental health (Greenlee et al., 2022; Rathgeber et al., 2019).

From a social and scientific point of view, these findings reinforce the importance of proposing and assessing interventions directed to couples and analyzing the effects of such interventions on parenting, mental health, and children’s behavior.

There are studies intended to promote good marital relationships. Aiming to investigate the effects of Relationship Checkup guided to couples, Fentz and Trillingsgaard (2016) performed a systematic literature review between 1995 and 2015, analyzing 12 randomized clinical trials. The interventions focused on strengths and weaknesses, aggressive behavior, risk factors, relationship history, occupation, and faith. The authors concluded that all the interventions positively affected marital relationships, and such effects remained in a 6-month follow-up. However, only five studies provided information on the children, and only three assessed the couples’ mental health.

Durães et al. (2020) and Doss et al. (2022) agree that couple interventions should alleviate distress by promoting acceptance, positive/constructive communication, and behavioral change. Hence, by improving marital relationships, interventions are expected to promote positive parenting and, consequently, improve children’s behaviors (Greenlee et al., 2022; Tomfohr-Madsen et al., 2020).

Baucom et al. (2018) verified the effects of an intervention teaching effective communication to 63 English couples in which one partner presented depression. The intervention improved satisfaction indicators for both partners, and the partner with depression experienced decreased depression indicators, showing that marital relationship is a relevant variable for the occurrence of depression. Durães et al. (2020) worked with 34 Brazilian couples, teaching communication skills, problem-solving strategies, dealing with expectations regarding marriage, and empathy. As a result, increased marital social skills were found along with fewer anxiety and depression indicators.

Doss et al. (2022) note that despite the advancements achieved in couple therapy, compared to other psychotherapy fields; few studies address the treatments proposed for marital problems. Hence, the previous discussion indicates the need to develop and apply couple interventions to promote affection, communication, stress control, emotional regulation, and problem-solving while verifying such interventions’ effects on parenting, children’s behavior, and couples’ mental health.

Objective

To describe the effects of a behavioral analytic therapy called Promove-Casais (Promote Couples) on positive/negative marital relationships, marital satisfaction, in addition to parenting, children’s behaviors, and couples’ mental health.

Method

Design

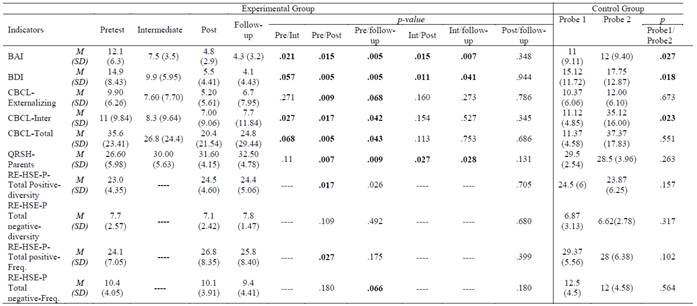

An experimental design was adopted (Cozby, 2014). It is characterized by randomly allocating participants to two groups: one group is exposed to an intervention condition, and the other is exposed to a non-intervention condition. A non-probability sampling, called convenience or accidental sampling, was used to recruit the participants (Cozby, 2014). In this study, the group exposed to the intervention condition was named the Experimental Group (EG), and the group exposed to the non-intervention condition was named the Control Group (CG). The participants were randomly assigned to each group (simple draw). Each couple was assigned a number (from one to nine), and the numbers were randomly drawn. The first number drawn was allocated to the EG, the second to the CG, and so on. Hence, the EG comprised five couples (four men and four women), and the CG comprised four couples (four men and four women). The groups’ baseline repertoire was compared using the Mann-Whitney Test, and equivalent results were found in all the study’s measures of interest (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparisons between the experimental and control groups regarding conjugality, parenting, child behavior, anxiety, and depression before the intervention (Mann-Whitney Test)

Notes: IHSC: Inventário de Habilidades Sociais Conjugais (Marital Social Skills Inventory); QRC: Questionário de Relacionamento Conjugal (Marital Relationship Questionnaire); BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; QRSH-Parents: Questionário de Respostas Socialmente Habilidosas versão pais (Questionnaire for Socially Skillful Responses-Parents’ version); RE-HSE-P: Roteiro de Entrevista de Habilidades Sociais Educativas Parentais (Parenting Social Skills Interview Guide); EG: experimental group; CG: control group; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

Ethical Aspects

The study project was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the hosting institution (CAAE: 55268216.9.0000.5398). Additionally, all the participants received booklets presenting the content addressed in the meetings. The participants’ feedback was collected after a 6-month follow-up, and the CG received the intervention after the study addressing the EG ceased.

Participants

Nine couples composed of a man and a woman participated in the study; hence, there were 18 participants (five couples in the EG and four in the CG). The criteria to select the sample were: being legally married or having a stable relationship for at least two years; having at least one child (a girl or a boy) aged up to 11, presenting no physical or cognitive impairment diagnosis (based on the parents’ reports); not receiving psychological or psychiatric assistance simultaneously to data collection (neither parents nor children); and being available to attend all the meetings together.

The men in the EG were aged from 34 to 45 years old (38.6 on average), women were aged between 27 and 37 (33 on average), while years of schooling ranged from 11 to 16 years (14 on average). The duration of the couples’ union ranged between four and 19 years (8.8 on average). Income ranged between three and six times the minimum wage (4.46 times the MW on average). According to the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria (ABEP, 2014), the participants belong to B2 and B1 economic classes, i.e., the middle class. The number of children ranged from one to three (four were boys and one was a girl), with an average of 1.6 children. The children’s age ranged between three and 10 (5.6 on average).

The men in the CG were aged between 27 and 41 years old (34.75 on average), the women were aged between 30 and 45 (35.75 on average), and years of schooling ranged from 11 to 18 years (15.25 on average). The duration of the couples’ union ranged between five and 19 years (8.75 on average). Income ranged between 1.6 and 1.7 times the minimum wage (3.35 times the MW on average). According to the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria (ABEP, 2014), the participants belong to B2 and B1 economic classes, i.e., the middle class. All the couples had only one child (three girls and one boy). The children were aged between two and eight (4.5 on average).

Regarding the participants’ workplace, most participants worked outside the home, except one man in the EG and one woman in the CG, who worked remotely from home, and one woman who was a homemaker. During the meetings, the women in both groups reported being the primary caregivers of children and responsible for managing the home, even though their partners helped them constantly. In addition, the groups were equivalent in terms of age and educational level (both presented a p = .905 -Mann-Whitney), and the same was true for the length of marriage/stable union, income, number of children, and children’s age (p = .730, p = .286; p = .413, p = .730, respectively -Mann-Whitney).

Sampling

The participants were recruited by disseminating the study in communication media (i.e., virtual newspapers, TV, AM/FM radio, and social media) at two points in time: April and November 2016. Thirty-three couples manifested interest, but only nine couples met the inclusion criteria.

Material and program

The program implemented here was published in Bolsoni-Silva (2010). It was initially named “Intervenção em Grupo para casais: descrição do procedimento analítico-comportamental” (Group intervention for couples: description of the behavior-analytic procedure), but it is currently named “Promove-Casais” (Promote Couples). In addition, the program adopts a booklet (Bolsoni-Silva, 2009), which was recently edited and published by Editora Juruá (Bolsoni-Silva, 2019) under the title “Relacionamento conjugal: quais comportamentos são importantes?” (Marital Relationships: what behaviors matter?). The intervention was implemented weekly in the laboratory of a public university. Ten to 12 meetings, lasting from 1 hour and 30 minutes to 2 hours, were held to develop the guiding topics; the author conducted the meetings. The couples in the Experimental Group were assisted separately; hence, five co-occurring interventions occurred.

The intervention, implemented in 10 and 12 meetings lasting from 1 hour and 30 minutes to 2 hours, taught positive communication, expression of affection, problem-solving, and social coping skills such as expressing negative feelings, divergent opinions, negotiating, and dealing with criticism. All the meetings were preceded by interviews with both partners, first simultaneously and then separated, for approximately two hours. The objective was to understand each participant’s case and establish specific objectives. The program is based on behavioral therapy using baseline case formulation procedures and functional analysis such as treatment, modeling, homework, problem-solving, and role-playing. Behavioral therapy uses behavior analysis theory and knowledge accumulated through basic and applied research to solve human problems. The functional analysis is the primary objective of assessment and intervention (Abreu & Abreu, 2017).

Instruments

Inventário de Habilidades Sociais Conjugais (IHSC; Marital Social Skills Inventory) (Villa & Del-Prette, 2012) is a self-report instrument that assesses an individual’s repertoire of specific social skills in a marital context. It is composed of 32 items addressing social behavior in a marital relationship, presenting a total score (general assessment of marital social skills) and five factors (F1-expressiveness/empathy, F2-self-assertiveness, F3-reactive self-control, F4- proactive self-control, and F5-assertive conversation). The Alpha coefficient ranged from .85 to .42. Del Prette et al. (2008) reported the instrument’s temporal stability.

Questionário de Relacionamento Conjugal (QRC; Marital Relationship Questionnaire) (Bolsoni-Silva, 2010) is a validated instrument (paper submitted) in which six sets of information are rated on a Likert scale: identifying the partner’s characteristics, expression of affection between partners, couple’s communication, identification of the partner’s positive and negative characteristics, and assessment of the marital relationship. The test-retest reliability used data from 12 couples and had a one-month interval between the applications: reliability was .84 for women and .94 for men (Spearman rho, p < .05); alpha was .871. The instrument differentiates the answers of men and women.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988, validated by Cunha, 2001). The instrument is composed of 21 items addressing anxiety symptoms. The scores range between zero and 63 and are divided into four levels: minimal anxiety level (zero to 10), mild anxiety (11 to 19), moderate anxiety (20 to 30), and severe anxiety (31 to 63). In this study, minimal and mild anxiety was considered non-clinical, while moderate and severe anxiety levels were considered clinical. The scale presents good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .92); the test-retest correlation ranged from .53 to .56; each item’s correlation ranged from .30 to .71. Convergent validity by correlation with IDATE was significant, with r = .78 in the correlation with Trait anxiety and r = .76 in the correlation with State anxiety.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961, validated by Cunha, 2001). It is a self-report scale composed of 21 items addressing depression symptoms. Four alternatives for answers (0 to 3) describe behaviors (attitudes, thoughts, and feelings) considered depressive symptoms. The scores range from zero to 63 and are divided into four levels: minimal (zero to 11), mild depression (12 to 19), moderate depression (20 to 35), and severe depression (36 to 63). In this study, minimal and mild depression was considered non-clinical, while moderate and severe depression levels were considered clinical. Test-retest ranged from .48 to .86 and discriminates groups with depression symptoms, with physical complaints, or without specific complaints, indicating evidence of discriminating validity.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001, validated by Bordin et al., 2013) has two versions that parents or caregivers of children and adolescents can answer. Its Brazilian version presented good sensitivity (87 %) and correctly identified 75% of the mild cases of problem behavior, 95 % of moderate, and 100 % of severe cases. In addition, CBCL has efficiently quantified parents’ answers regarding their children’s behaviors (Bordin et al., 2013). In this study, we adopted the version for children aged between 1.5 and 5, composed of 99 items. The version for children and adolescents aged six to 18 comprises 118 items. The instrument assesses internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. In this study, the fathers and mothers of children completed this instrument. Scores in the borderline and clinical ranges were found. According to the instrument’s manual, scores in the normal range were considered non-clinical.

Questionário de Respostas Socialmente Habilidosas (QRSH-Pais; Questionnaire for Socially Skillful Responses-Parents’ version). This instrument was validated by Bolsoni-Silva and Loureiro (2020b) and presented good results concerning discriminative, construct, concurrent, and predictive validity; Cronbach’s alpha was equal to .94. A list of items addressing children’s social skills is rated on a 3-point Likert scale, and the cut-off point indicates problem behavior based on the ROC curve. This questionnaire is free to use.

Roteiro de Entrevista de Habilidades Sociais Educativas (RE-HSE-P; Parenting Social Skills Interview Guide) (Bolsoni-Silva et al., 2016). It assesses positive and negative interactions established between parents and children and presents good discriminating and construct valid indicators and test-retest reliability. Internal consistency for the 70 items obtained a Cronbach’s alpha equal to .846. It has two factors: Total Positive (parenting social skills, children’s social skills, and context) and Total negative (negative parenting practices and problem behavior). The instrument also investigates the participants’ sociodemographic data, such as the number of children and children’s age, educational level, marital status, family income, employment, and occupation.

Data Collection

After the ethics committee approved the study and it was disseminated to potential participants, each of the couples selected was individually interviewed, and later, each individual was interviewed separately. Then, the participants received clarification regarding the program and study and signed free and informed consent forms. Next, a new interview was held to apply the instruments previously described, and all the instruments were applied before the intervention (EG pre-test and CG probe 1), after five meetings (intermediate measure), after the intervention (EG post-test and CG probe 2), and after a six-month follow-up.

Data treatment and analysis

Data were collected with the instruments and tabulated according to the instruments’ manuals. The groups’ different measures were compared (Wilcoxon test).

Results

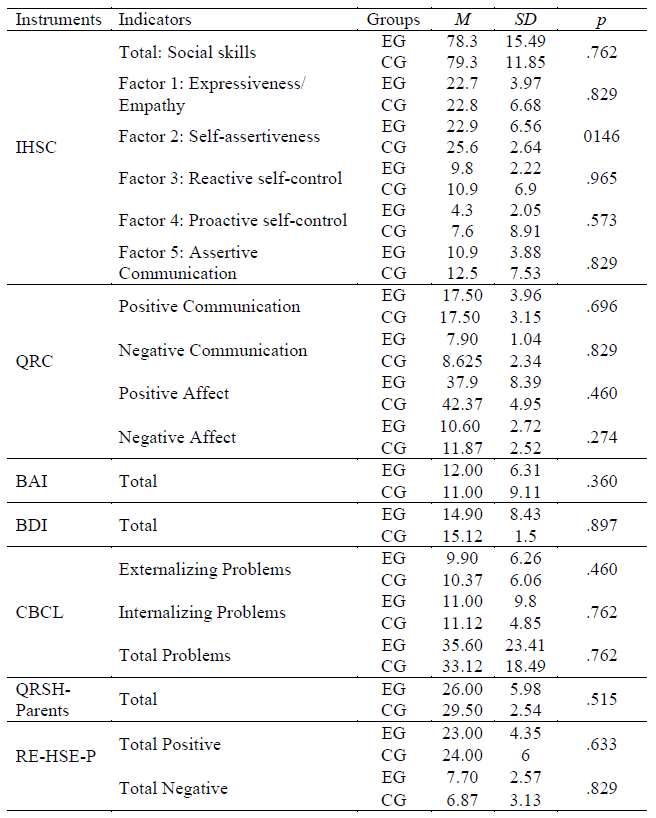

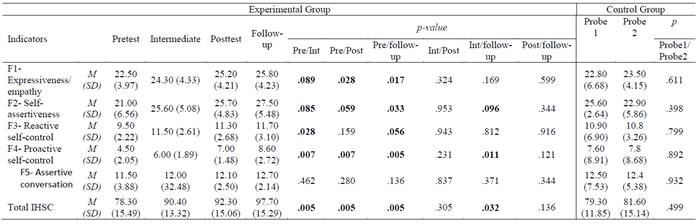

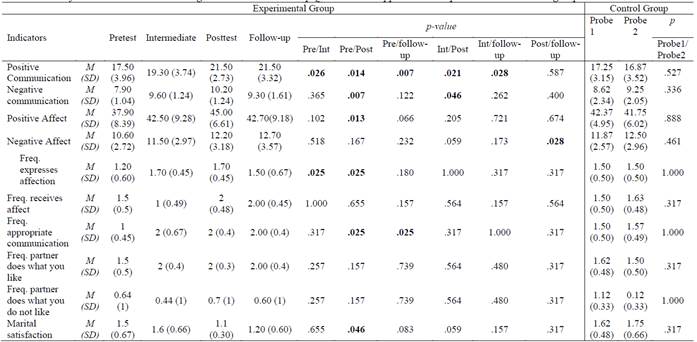

The results are organized to present the comparisons between the Experimental (EG) and Control (CG) groups concerning the marital relationship measures (Tables 2 and 3), mental health indicators (anxiety and depression), children’s behaviors (problem behavior and social skills), and parent-child relationships (Table 4).

Table 2 shows that, except for Factor 4 (proactive self-control), all IHSC measures presented statistically significant improvement in the intermediary measurement and post-test. Furthermore, the improvements remained in the follow-up, with reports of increased expressiveness/empathy, self-assertiveness, reactive self-control, and assertive conversation, leading to higher total scores. The control group showed no changes.

The results in Table 3 show that the experimental group more frequently reported positive communication and fewer instances of negative communication in the intermediate measurement (after the intervention). The frequency and diversity of positive affect between the post-test and follow-up also increased while the diversity of negative affect decreased. Moreover, the marital satisfaction score obtained by the EG increased between the pre- and post-test, while no changes were found in the CG.

Table 4 shows a statistically significant decrease in the anxiety and depression indicators collected on the intermediate measurement and post-test, which remained in the follow-up. Additionally, considering the cutoff points of BAI for anxiety indicators, only two participants in the experimental group and two in the control group presented clinical scores in the baseline; the EG participants no longer obtained clinical scores after the intervention, while the CG participants continued presenting clinical scores. Regarding depression indicators obtained with BDI, five participants in the EG and three in the CG obtained clinical scores in the baseline. All the participants in the EG no longer obtained such scores after the intervention, but the three participants in the CG continued to present clinical scores for depression.

The assessment of problem behaviors using CBCL also indicated statistically significant improvement in the EG regarding their children’s externalizing and total problems. However, the same did not occur in the CG. Few children obtained clinical scores in this measure in the first assessment: two children in the EG presented externalizing problems, three internalizing problems, and one total problems; only two children in the CG presented internalizing problems and one total problems. According to this criterion, only one child in the EG continued obtaining clinical scores for externalizing, internalizing, and total problems after the intervention. Nonetheless, the CG obtained worse scores in Probe 2, i.e., three children presented internalizing problems and two externalizing problems.

The children’s social skills scores improved significantly after the intervention in the EG and remained in the follow-up. Such an outcome was not observed in the CG. Regarding child rearing practices, the EG showed an increase in total positive practices and a decrease in the frequency of total negative practices, results that remained in the follow-up. No changes were found in the CG.

Table 2: Results of the Wilcoxon Test concerning the IHSC indicators of the experimental and control groups

Note:Pre: pretest; Int: intermediate measure; Post: posttest; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

Table 3: Results of the Wilcoxon test concerning the Marital Relationship Questionnaire applied to the experimental and control groups

Notes: Freq: Frequency; Pre: pretest; Int: intermediate measure; Post: posttest; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

Discussion

This study describes a behavioral therapy (Abreu & Abreu, 2017) intervention designed for couples (Promove-Casais) and presents the effects on marital relationship, parenting, child behavior, and mental health. The results show the behavioral acquisition of positive communication, affect, self-control, and problem-solving capacity in addition to a decrease in negative communication and negative affect. Moreover, marital satisfaction increased after the intervention, as did positive parenting indicators and children’s social skills and mental health. At the same time, the frequency of negative parent-child interactions and problem behaviors fell. However, only the EG presented such outcomes that remained in the follow-up. Considering that the control and experimental groups were equivalent in the baseline measures, such an improvement can be attributed to the intervention.

After the intervention, the couples developed constructive communication skills, expression of affection, and problem-solving strategies, which favored marital satisfaction (Durães et al., 2020; Kazim & Rafique, 2021; Wagner et al., 2019). This study’s findings corroborate other studies addressing couple counseling (Doss et al., 2022; Durães et al., 2020; Fentz & Trillingsgaard, 2016), showing that improved communication, affection, and problem-solving capacity decrease the frequency of conflicts and improve the quality of marital relationships and satisfaction.

Regarding depression and anxiety indicators, some individuals in the experimental and control groups obtained clinical scores for anxiety (20 % and 25 %, respectively) and depression (50 % and 37.5 %, respectively) in the baseline. These results corroborate the findings of authors reporting a relationship between marital conflicts and mental health problems (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Choi & Jung, 2021; Hsiao, 2017; Vafaeenejad et al., 2018). However, similarly to Baucom et al. (2018) findings, this study’s results do not allow us to state that couples with marital problems and seeking assistance necessarily present mental health problems.

On the other hand, the study showed that mental health problems, i.e., anxiety and depression, improved in the experimental group after the intervention. In contrast, the control group continued to experience symptoms, corroborating the role of the intervention implemented among couples to decrease mental health problems indicators (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Baucom et al., 2018; Choi & Jung, 2021; Durães et al., 2020; Hsiao, 2017; Vafaeenejad et al., 2018). In their literature review, Fentz and Trillingsgaard (2016) found that few intervention studies addressing couples included mental health and child behavior measures. Depression is known to increase the risk of parents using negative practices (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Greenlee et al., 2022; Vafaeenejad et al., 2018; Zalewski et al., 2017) and harm marital relationships (Vafaeenejad et al., 2018). Therefore, studies on family interactions (marital or parental interactions) should include the assessment of mental health indicators.

Regarding the children’s behavior, a small portion obtained scores in the clinical range for problem behavior, showing that problem behaviors do not exclusively result from marital conflicts. However, only the experimental group statistically decreased scores for externalizing, internalizing, and total problems, confirming that marital relationship is relevant for the occurrence of such problems (Bolsoni-Silva, 2010; Mark & Pike, 2017). After the intervention, one of the children in the experimental group continued to obtain a clinical score for problem behavior, suggesting the need for additional interventions, whether addressing the child and parents, or the parents focusing on parental practices.

Furthermore, the socially skillful behaviors of the children in the experimental group presented a statistically significant increase, confirming the relationships reported by screening studies between harmonious marital relationships and children’s social skills (Bolsoni-Silva, 2010; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017; Mark & Pike, 2017). The results also enable verifying the inverse relationship between problem behavior and social skills among children (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a).

Regarding parenting, the intervention improved parent-child relationships through increased positive interactions and decreased negative interactions. Based on other studies’ results, this was an expected outcome (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017), as various studies report the relationship between marital problems and parent-child relationship (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019; Choi & Jung, 2021; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017). This study corroborated this finding, considering that improved marital relationships favored improved parent-child interactions. The use of negative child-rearing practices to regulate child behavior increases the risk of problem behavior (Greenlee et al., 2022; Mark & Pike, 2017; Vafaeenejad et al., 2018) and decreases the occurrence of social skills among children (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2020a; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017; Mark & Pike, 2017). On the contrary, positive parenting is associated with children’s social skills (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2017).

Final Considerations

This study verified that a direct effect of Promove-Casais, a behavioral analytic therapy program, was improved marital relationships, which consequently resulted in improved parent-child interactions, parents’ mental health, and children’s behaviors. These variables are well documented in the literature, but the specificities of such interactions in the Brazilian context still require further research.

This study’s strengths include its experimental design, in which experimental and control groups, comparable and equivalent regarding the study’s measures of interest and sociodemographic variables, are addressed.

Limitations include the small number of participants originated from a single city and the exclusive use of self-reporting measures, even though all were validated measures. Future studies are suggested to increase the number of participants from other locations, and include direct observation measures. Testing the Promove-Casais program among families with children presenting problem behaviors would be interesting to verify the effect of the program by itself and when combined with other interventions (directed to parents and/or children) on conjugality, parenting, children’s behaviors and mental health. The program is believed to be socially relevant in promoting families’ quality of life and health; hence, it could be adopted in public policies with this purpose. Future studies could apply and verify the effects of the program among couples without children and those with a history of domestic violence.

REFERENCES

Abreu, P. R. & Abreu, J. H. S. S. (2017). Ativação comportamental: Apresentando um protocolo integrador no tratamento da depressão. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 19(4), 238-259. https://doi.org/10.31505/rbtcc.v19i3.1065 [ Links ]

Achenbach, T. M. & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families. [ Links ]

Baucom, D. H., Fischer, M. S., Worrell, M., Corrie, S., Belus, J. M., Molyva, E., & Boeding, S. E. (2018). Couple‐based intervention for depression: An effectiveness study in the National Health Service in England. Family Process, 57(2), 275-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12332 [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893-897. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893 [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561-571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. & Loureiro, S. R. (2019). Práticas parentais: conjugalidade, depressão materna, comportamento das crianças e variáveis demográficas. Revista Psico-USF, 24, 69-83. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712019240106 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. & Loureiro, S. R. (2020a). Behavioral problems and their relationship to maternal depression, marital relationships, social skills and parenting. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 33, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-020-00160-x [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. & Loureiro, S. R. (2020b). Evidence of validity for Socially Skillful Responses Questionnaires: SSRQ-Teachers and SSRQ-Parents. Psico-USF, 25(1), 155-170. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712020250113 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2009). Relacionamento conjugal: quais comportamentos são importantes? Suprema. [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2010). Intervenção em grupo para casais: descrição de procedimento analítico-comportamental. In M.C. Garcia; P. R. Abreu; E. N. P. Cillo; P. B. Faleiros & P. Piazzon (Eds.), Sobre Comportamento e Cognição. Terapia Comportamental e Cognitivas (pp. 151-181). ESETec. [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2019). Relacionamento conjugal: quais comportamentos são importantes? Juruá. [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., Loureiro, S., & Marturano, E. M. (2016). Roteiro de entrevista de habilidades sociais educativas parentais (RE-HSE-P). Manual Técnico. HOGREFE/Cetepp. [ Links ]

Bordin, I. A., Rocha, M. M., Paula, C. S., Teixeira, M. C. T. V., Achenbach, T. M., Rescorla, L. A., & Silvares, E. F. M. (2013). Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher’s Report Form (TRF): an overview of the development of the original and Brazilian versions. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 29(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2013000100004 [ Links ]

Choi, E. & Jung, S. Y. (2021). Marital satisfaction and depressive symptoms among Korean couples with young children: dyadic autoregressive cross-lagged modeling. Family Relations, 70(5), 1384-1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12570 [ Links ]

Cozby, P. C. (2014). Métodos de pesquisa em ciências do comportamento (P. I. Cunha Gomide & E. Otta, trads.). Atlas. [ Links ]

Cunha, J. A. (2001). Manual da versão em português das Escalas Beck. Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., Villa, M. B., Freitas, M. G., & Del Prette, A. (2008). Estabilidade temporal do Inventário de Habilidades Sociais Conjugais (IHSC). Avaliação Psicológica, 7(1), 67-74. [ Links ]

Doss, B. D., Roddy, M. K., Wiebe, S. A., & Johnson, S. M. (2022). A review of the research during 2010-2019 on evidence‐based treatments for couple relationship distress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48(1), 283-306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12552 [ Links ]

Durães, R., Khafif, T. C., Lotufo-Neto, F., & Serafim, A. de P. (2020). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral couple therapy on reducing depression and anxiety symptoms and increasing dyadic adjustment and marital social skills: An exploratory study. The Family Journal, 28(4), 344-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720902410 [ Links ]

Fentz, H. N & Trillingsgaaed, T. (2016). Checking up on couples: A meta-analysis of the effect of assessment and feedback on marital functioning and individual mental health in couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(1), 31-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12185 [ Links ]

Greenlee, J. L., Piro-Gambetti, B., Putney, J., Papp, L. M., & Hartley, S. L. (2022). Marital satisfaction, parenting styles, and child outcomes in families of autistic children. Family Process, 61(2), 941-961. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12708 [ Links ]

Hosokawa, R. & Katsura, T. (2017). Marital relationship, parenting practices, and social skills development in preschool children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0139-y [ Links ]

Hsiao, Y. (2017). Longitudinal changes in marital satisfaction during middle age in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 20(1), 22-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12161 [ Links ]

Kazim, S. M. & Rafique, R. (2021). Predictors of marital satisfaction in individualistic and collectivist cultures: a mini review. Journal of Research in Psychology, 3(1), 55-67. https://doi.org/10.31580/jrp.v3i1.1958 [ Links ]

Mark, K. M. & Pike, A. (2017). Links between marital quality, the mother-child relationship and child behavior: a multi-level modeling approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(2), 285-294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416635281 [ Links ]

Rady, A., Molokhia, T., Elkholy, N., & Abdelkarim, A. (2021). The effect of dialectical behavioral therapy on emotion dysregulation in couples. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH, 17, 121. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017902117010121 [ Links ]

Rathgeber, M., Bürkner, P. C., Schiller, E. M., & Holling, H. (2019). The efficacy of emotionally focused couples therapy and behavioral couple’s therapy: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(3), 447-463. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12336 [ Links ]

Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M., Giesbrecht, G., Madsen, J. W., MacKinnon, A., Le, Y., & Doss, B. (2020). Improved child mental health following brief relationship enhancement and co-parenting interventions during the transition to parenthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (3), 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030766 [ Links ]

Vafaeenejad, Z., Elyasi, F., Moosazadeh, M., & Shahhosseini, Z. (2018). Psychological factors contributing to parenting styles: A systematic review. F1000Research, 7, 906. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.14978.1 [ Links ]

Villa, M. B. & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2012). Inventário de habilidades sociais conjugais: IHSC. Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Wagner, A., Mosmann, C. P., Scheeren, P., & Levandowski, D. C. (2019). Conflict, conflict resolution and marital quality. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 29, e2919. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4327e2919 [ Links ]

Zalewski, M., Thompson, S. F., & Lengua, L. J. (2017). Parenting as a moderator of the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on preadolescent adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(4), 563-572. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1030752 [ Links ]

How to cite: Ferraz, F. I. A. L. & Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2023). The effects of the Promove-Casais program on conjugality, parenting, mental health, and child behavior. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2695. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2695

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. F. I. A. L. F. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; A. T. B-S. in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: October 06, 2021; Accepted: May 18, 2023

text in

text in

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI