Work and family constitute two central domains in the life of adult individuals, which have been studied independently for a long time (Allen et al., 2014). The social and economic changes that have taken place in recent decades, however, have made the management of work and family life closely related, which has led researchers to pay more attention to the different forms of integration between work and family (Allen et al., 2014).

One of the aspects of this integration concerns the work-family interface, which analyzes the combination of the work and family functions, that is, the relationships between the activities, attitudes, and interpersonal relationships circumscribed to the work sphere and the attributes in the family sphere (Ford et al., 2018). Initially, the studies in this area were mainly focused on the work-family conflict, according to which participation in the work context made it difficult to participate in the family (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985).

More recently, however, scholars have also come to recognize the positive effects of combining work and family functions (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). It is in the wake of that development that the work-family enrichment construct emerges, which emphasizes the fact that resources earned at work promote better family performance and, therefore, personal quality of life (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006).

Based on the premise that both conflict and work-family enrichment are based on the link between work and family, Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012) proposed the Work-Family Resources Model (WF-R). According to the model, conflict and work-family enrichment are independent but closely related processes, which is why they need to be studied together. No studies were found, however, that focused on conflict and work-family enrichment at the same time. To contribute to a better understanding of this matter, in this study, the conflict and work-family enrichment processes were tested jointly.

According to the WF-R Model, conflict and enrichment can be conceived as processes in which contextual work demands (in the case of conflict) and resources (in the case of enrichment) impact the family outcomes (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). This approach does not imply, however, the use of explicit measures of the work-family interface, but rather instruments that measure the resources, the work demands, and family performance separately.

This model, however, requires more empirical verification, as no studies were found that empirically tested the relationships that it advocated. In this sense, only two studies were found, testing the family's influence on the work in the framework of the WF-R Model (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2017; Tement, 2014). One of the objectives of this study was to identify together the relationships of a contextual work demand (perceived work demand) and a contextual work resource (social support at work) with a family income, put in practice through the flourishing in the family, a construct whose nomological network still lacks research.

The WF-R Model posits the mediating role of personal resources in the relationships of work demands and contextual resources with the outcomes in the family. Research on the mediating role of personal resources in the relationships between work demands and resources and family outcomes has been neglected. Thus, this study tested the robustness of the WF-R Model, testing the mediating role of a personal resource in the relationships between work demands and contextual resources, and family outcomes. More specifically, the mediating role of positive psychological capital in the relationships between work demands and social support at work with flourishing in the family was analyzed.

Also, according to the WF-R Model, the relation of work demands and contextual resources with personal resources is moderated by macro resources (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). No studies have been found, however, on the moderating role of macro resources in those relationships. In this sense, the organizational culture, operated by values associated with employee satisfaction and well-being, was adopted as a macro resource, to permit a better understanding of the cultural factors that moderate the relationships of work demands and social support at work with positive psychological capital.

According to the WF-R Model, the contextual work demands derive from the work context the individual is part of and can be classified in quantitative (are associated with the overload, that is, they concern the performance of several tasks at the same time), emotional (drain the individual's emotions as they relate to issues that impact him personally), physical (related to tasks that require physical effort in the work context) and cognitive (associated with tasks that require great concentration at work). Furthermore, the contextual work demands are negative predictors of family outcomes, which are subdivided into production (related to the efficient performance of domestic tasks, to high-quality care for family members, and leisure), behavior (outcomes relate to family member availability, responsibility, and the promotion of a safe home environment) and attitude (refer to the beliefs and feelings the individual presents about his family and include, for example, family satisfaction and good relationships with family members, as well as well-being and happiness related to the family; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012).

In this research, a quantitative demand called perceived work demand has been adopted, which is related to the individual's perception of his level of responsibility at work (Gabardo-Martins & Ferreira, 2019). As an attitude-related outcome, flourishing in the family was adopted. This construct consists of an indicator of well-being, which integrates the eudaimonic and hedonic perspectives. In this sense, it is associated with the absence of mental illness, emotional vitality, frequency of positive emotions, and positive functioning in the family (Keyes, 2002). In this sense, flourishing in the family means to live and not only to exist, but that is also, to present good functioning in the psychological and social aspects inherent to the family (Keyes, 2002).

In the perspective of the WF-R Model, the contextual work demands can lead the individual to exhaustion, which may compromise his well-being in the family (Ten Brummelhuis & Baker, 2012). Therefore, it is to be expected that the fact that the individual realizes that he needs to perform several tasks at the same time and that he presents a high degree of responsibility in his work leads him to experience negative feelings at work that can be transferred to his family. As a result, he would feel less valued by his family members and would tend to present symptoms of mental illness and the absence of positive emotions in his family context.

Consistently with those assumptions, empirical studies have evidenced negative relationships of work demands with family well-being (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2021; Kutty, 2018; Skomorovsky et al., 2015). Based on these statements, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 1: The perceived work demands are negatively associated with flourishing in the family negatively.

According to the WF-R Model, the contextual work resources are located in the social context of the individual and can be classified into social support of the organizational members, autonomy, development opportunities, and feedback (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). In this study, social support at work was adopted, which relates to the extent to which the individual perceives that the social support of the supervisor and his colleagues exists and is available to him. It refers, therefore, to the quality of the interpersonal relationship of the individual with the supervisor and colleagues (Tamayo et al., 2000).

According to Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012), contextual work resources can revitalize individuals and, consequently, raise the level of their well-being in the family, that is, the contextual resources of the work constitute positive predictors of family outcomes. It would be expected, then, that the fact that work offers rewarding experiences to the individual, provided by the quality of the interpersonal relationships in the work context, leads him to experience positive feelings that can be transferred to his home. Thus, he would present emotional vitality, positive emotions, and good functioning in his family. Consistently with those claims, empirical studies have evidenced that work resources have had positive relationships with family well-being (Chan et al., 2019). Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 2: Social support at work is positively associated with flourishing in the family.

Personal resources are associated with the psychological abilities and energies that are inherent in the individual and can help him to adapt more easily to the changes and circumstances of life (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). In the current study, the individual resource was positive psychological capital, which consists of a positive state manifested in feelings of self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience (Luthans et al., 2007).

According to the WF-R Model, personal resources play a mediating role in the relationships of work demands and contextual resources with family outcomes. In this sense, the contextual work demands diminish personal resources, which, in turn, interfere in family outcomes. On the other hand, the contextual work resources increase the personal resources that, consequently, facilitate family outcomes (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012).

Based on the model by Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012), it would be expected, therefore, that individuals with more intense degrees of responsibility in their work had more difficulties developing their positive psychological capacities, which would lead them to demonstrate more symptoms of mental illness and less positive emotions in their family context. Also, individuals who experienced positive experiences at work and received the support of their supervisor and colleagues would be able to develop their positive psychological capacities and achieve growth, which would lead them to present emotional vitality, positive emotions, and proper family functioning.

In line with those assertions, empirical research has evidenced the mediating role of personal resources (self-efficacy) in the relationship of contextual resources with family satisfaction (Azim et al., 2019). Thus, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 3a: Positive psychological capital mediates the negative relationship between perceived work demand and flourishing in the family.

Hypothesis 3b: Positive psychological capital mediates the positive relationship between social support at work and flourishing in the family.

The WF-R Model argues that macro resources are moderators of the relationships between work demands and contextual resources and personal resources, to counterbalance the negative effects of the demands and enhance the positive effects of contextual resources (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). These resources can be conceptualized as economic, social, and/or cultural characteristics of the system the individual is part of.

In this study, the macro resource adopted was the organizational culture, which can be understood as a set of standards that are shared by the employees of an organization and determine how they should act, think and make their decisions. According to Ferreira and Assmar (2008), organizational culture can be seen as a construct composed of seven factors, divided into four value factors and three organizational practice factors: values of cooperative professionalism; values of strictness in the hierarchical power structure; values of competitive and individualistic professionalism; values associated with employee satisfaction and well-being; external integration practices; reward and training practices; interpersonal relationship promotion practices.

In this study, however, only the dimension of values associated with employee satisfaction and well-being was adopted, which refers to the valuation of employee well-being and satisfaction, to make the workplace pleasant and enjoyable (Ferreira & Assmar, 2008), because this dimension is a positive cultural characteristic of the organization the individual is inserted in. It would thus be expected that the negative impact of the perception of more intense degrees of responsibility in the family on the personal growth provided by the increase of positive psychological capacities would be attenuated in organizations whose cultures value employee well-being. In addition, the positive influence of supervisors' and co-workers' social support on the development of positive psychological skills should become more pronounced in organizations whose cultures privilege the well-being of their employees.

Consistent with those statements, different studies have demonstrated the moderating role of the organizational culture, such as Saha and Kumar's (2018) research, which has shown that the impact of affective commitment on job satisfaction is stronger in organizations with innovative cultures and support. In this sense, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 4a: The organizational culture associated with values that prioritize employee satisfaction and well-being moderates the relationship of perceived work demand to positive psychological capital, which is weaker in organizations with this type of organizational culture.

Hypothesis 4b: The organizational culture associated with values that prioritize employee satisfaction and well-being moderates the relationship of social support at work to positive psychological capital, which is stronger in organizations with this type of organizational culture.

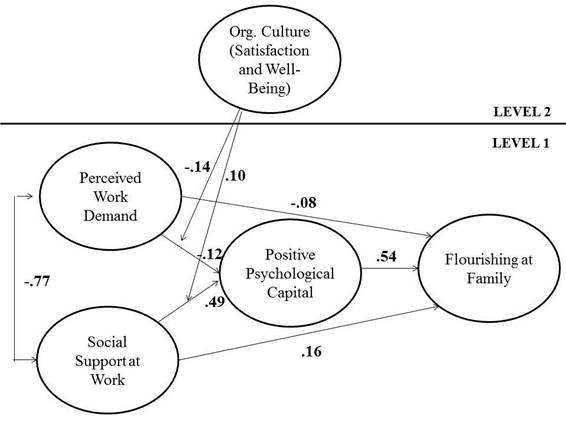

In summary, in this paper, we tested the relationships between the perceived work demands and social support at work with flourishing in the family, as well as the mediating role of positive psychological capital in these relationships. In addition, we sought to identify the moderating role of organizational culture associated with values that prioritize employee satisfaction and well-being in the relationships between work demands and social support at work with positive psychological capital. Figure 3 summarizes the relationships studied.

Method

Participants and procedures

Initially, the research was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the authors' institution. After approval, data were collected online, when the respondents expressed their agreement to participate in the survey by completing the Informed Consent Form. A form was created in Google Forms, including the instruments used.

The research is characterized as descriptive and of the survey type, using a quantitative approach. The sample was of convenience, in which one individual from each organization was contacted and invited to participate through messages posted on Facebook and Whatsapp. Accepting the invitation and providing that they worked in organizations with at least 20 employees, they were asked to take responsibility for collecting data in the organizations where they worked, through the survey link. To try to guarantee only one response per participant, they had to log in to their Google account to access the form.

Employees from 132 different Brazilian and multinational organizations located in Brazil were contacted. At the end of the survey, the sample consisted of 50 different organizations (return rate of 37.88 %, per organization), from 14 Brazilian states, most notably the states of São Paulo (24 %) and Rio de Janeiro (14 %). Of the total number of participating organizations, 60 % were large, 12% medium-sized and 28 % small companies, according to the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística ranking (2020).

Participants were 1052 employees of both sexes (72.5 % women). As for marital status, the majority were married or lived with a partner (85.5 %). Regarding education, 43.8 % graduated. 564 participants (53.6 %) reported having children. The age ranged from 18 to 79 years (M = 34.50; SD= 10.01) and the length of experience ranged from one to 44 years (M= 13.69; SD= 10.21). The inclusion criterion used was that respondents should be 18 years of age or older and be married or have children, as the model investigates the relationship between work and family.

Instruments

Social support at work was measured using the social support at work subscale of the Perceived Organizational Support Scale (Tamayo et al., 2000), consisting of five items, answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to always (5). Example item: My group cares about the well-being of co-workers. The subscale had an internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) of .93.

The perceived work demands were analyzed using the work factor of the Brazilian version of the Perceived Work and Family Demands Scale (Gabardo-Martins & Ferreira, 2019), composed of five items, to be answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from I strongly disagree (1) to I strongly agree (5). Example item: My work requires my full attention. The subscale obtained an internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) of .95.

The positive psychological capital was assessed through the Psychological Capital Scale (Luthans et al., 2007), adapted for Brazil (Kamei et al., 2018) and composed of 12 items, to be answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from I strongly disagree (1) to I strongly agree (6). Example of item: At work, I can do things without anyone's help. The internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) was equal to .94.

The flourishing in the family was measured using an adaptation of the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010) to the family context, similar to the adaptation by Mendonça et al. (2014) to the work context. The instrument has a single-factor structure and consists of eight items, to be answered on seven-point Likert scales, varying from I completely disagree (1) to I completely agree (7). Example item: In my family, people respect me. The instrument had an internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) equal to .96.

To evaluate the organizational culture, a subscale of values associated with employee satisfaction and well-being was used, the reduced version of the Brazilian Organizational Culture Assessment Tool (Ferreira & Assmar, 2008), composed of five items to be answered on five-point Likert scales, ranging from not applicable at all (1) to fully applicable (5). Example item: Personal needs and employee well-being are a constant concern of the company. The subscale obtained an internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) of .94 in this study.

In addition to the considered instruments, a sociodemographic questionnaire was used to obtain information about the sample. In it, different characteristics were asked, such as gender, marital status, education, whether or not they had children, age, length of service, etc.

Data analysis

The measuring model was verified, in which the model of five different and correlated factors was tested, through MCFA. In the configuration of the models, the factor loadings were set equal between the levels (cross-level invariance). It was also verified if the model of five different and correlated factors fit the collected data and if the five latent variables were represented by their respective items.

After confirming the measuring model, the structural model was tested. Firstly, the analysis of the first-level structural model was carried out to verify the mediating role of positive psychological capital (PPC) in the relationships of perceived work (PWD) demands and social support at work (SSW) with flourishing in the family (FF). In the first step, the direct effects of the PWD and SSW on the FF were tested. In the next step, the mediating variable (PPC) was inserted into the model, to verify if the predictor variables were related to the mediating variable and whether it was related to the dependent variable. The standard error of the indirect effect of the mediating variable between the independent variables and the dependent variable was estimated using the bootstrap procedure, with 500 replications. The 95% confidence interval was used for direct and indirect effects.

Next, we tested the moderation of the organizational culture associated with values that prioritize employee satisfaction and well-being (level 2), the relationships between the independent variables and the mediator variable (level 1), through an interaction effect between levels (cross-interaction effect). In all tests, the estimation method of maximum likelihood parameters (ML) was used. To evaluate the goodness of fit, the following indices were analyzed: chi-square (the higher the value of χ2, the worse the adjustment); Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA should be inferior to .08, accepting values up to .10); Tucker-Lewis Index and Comparative Fit Index (TLI and CFI should be superior to .90, preferably to .95) (Xia & Yang, 2019).

Results

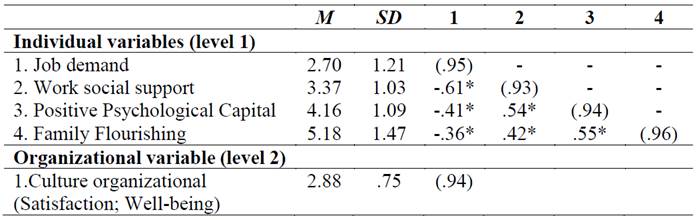

Initially, the descriptive statistics of the scales were calculated, as well as Pearson's correlation between the study variables (Table 1). The complete model, with the five variables inserted as distinct factors (χ2 = 2316.33 (56), RMSE = .08; CFI = .91; and TLI = .90) presented good fitness indices. It should also be noted that factor loadings varied from .72 to .92 (M= .84), in a demonstration that the items can be explained by their respective latent variables.

Table 1: Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between the research variables

Note: Cronbach’s alpha coefficients between parentheses; Number of workers = 1,052; Number of organizations = 50. * p < .01.

For the hypothesis test, the model was configured with the first-level variables observed (calculated from the average item scores of each scale) and with the latent variable of the organizational culture dimension for the first and second levels of analysis. Initially, at level 1, the direct effect of the PWD and SSW on FF was verified. The results indicated that these effects were significant (PWD: Beta = -16, p <.001; SSW: Beta = .32; p <.001), which confirms Hypotheses 1 and 2. The insertion of the variable PPC in the model showed that the independent variables presented positive and significant associations with the mediator variable (PWD and PPC: Beta = -.12; p <.001; and SSW and PPC: Beta =. 49, p <.001), and that the relationship between the mediating variable and the dependent variable (Beta = .60; p <.001) was also positive and significant. In addition, the indirect effects of these relationships were also statistically significant (PWD-PPC-FF: Beta = -07; p <.001; SSW-PPC-FF: Beta = .29; p <.001). It was also observed that, in the presence of the mediating variable, the direct effects of the PWD and SSW on the FF dropped, although they remained significant (PWD-FF: Beta = -.13; p < .01; SSW-FF: Beta = .16; p < .01). In short, the PPC partially mediated the relation of the PWD with FF, as well as between the SSW and FF, which confirms Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

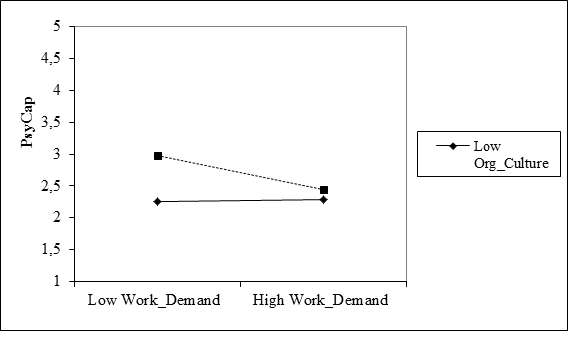

Regarding the nature of the interaction effects between the organizational culture associated with employee satisfaction and well-being values and the PWD on PPC, it was observed that this cultural dimension negatively moderated the negative relation of the PWD with the PPC, in the sense that the higher the level of this type of culture in the organization, the weaker the impact of PWD on PPC (Figure 1). These findings confirm Hypothesis 4a.

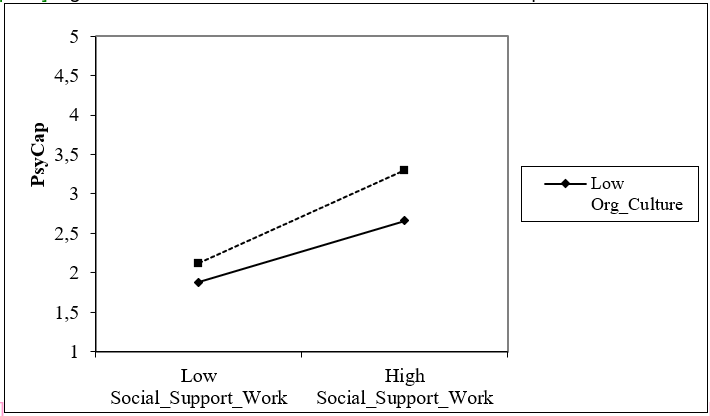

A significant effect of the interaction between organizational culture associated with employee satisfaction and well-being values and SSW on PPC was observed. It can be affirmed, therefore, that this type of culture positively moderated the relationship between SSW and PPC. Thus, in organizations with high levels of organizational culture associated with values of employee satisfaction and well-being, the influence of SSW on PPC is stronger (Figure 2). These results confirm Hypothesis 4b. Figure 3 shows the graphical representation of the final model, with the non-standard parameters.

Discussion

Although conflict and work-family enrichment are independent but closely interrelated processes, the literature has neglected studies that address both processes at the same time. To contribute to a better understanding of this issue, this study tested a model that integrates both conflict and work-family enrichment. The results showed that the perceived work demands presented a negative relationship with flourishing in the family and that social support at work showed a positive relationship with flourishing in the family, both relationships being mediated by positive psychological capital. The study also highlighted that the organizational culture values associated with employee satisfaction and well-being mitigated the negative relationships between perceived work demands and flourishing in the family, and emphasized the positive relationship of social support at work with flourishing in the family. These findings entail important contributions to the work-family interface literature.

Theoretical Implications

The main theoretical contribution of this study was to demonstrate how the different processes in the work-family interface can occur, and how they can contribute to the quality of life in the family context. One of the ways to obtain these results is to reduce the levels of perceived work demands, as the results indicated negative relationships between work demands and family well-being. These findings are consistent with other studies (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2021; Kutty, 2018). In addition, they have shown that individuals with many work demands are unable to reconcile work and family life and, consequently, do not achieve positive results in their families (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2021).

Another way to achieve better results in the family relates to the social support individuals receive from their supervisors and colleagues, as a positive relationship was observed between social support at work and flourishing in the family, which can strengthen the conclusions of previous studies (Chan et al., 2019) regarding the importance of work resources for family well-being. These results indicate that supervisors and co-workers constitute important sources of social support for workers and that this support is also reflected beyond the work environment, as it also allows for increased levels of well-being in the individual's family (Chan et al., 2019).

The results also indicated that the psychological capital partially mediated the relationships of perceived work demands and social support at work with flourishing in the family. These findings support earlier studies (Azim et al., 2019) on the mediating role of personal resources in the relationships between contextual resources and well-being. In addition, they contribute to a greater understanding of the role of personal resources in linking work variables to family variables. Thus, the mediating role of a personal resource was identified in the relationships not only of work resources but also of work demands with family well-being.

The results of this study also showed that the organizational culture associated with values that prioritize employee satisfaction and well-being mitigated the negative relationship between the perceived work demands and positive psychological capital, and enhanced the positive relationship of social support at work with positive psychological capital. These findings strengthen the conclusions of other studies (Saha & Kumar, 2018) regarding the moderating role of organizational culture. This study shows that in organizations with higher levels of this type of culture, the impact of work demands on positive psychological capacities tends to decrease, while the influence of social support at work on these capacities is enhanced.

It should also be noted that the results reported here contribute to the advancement of the literature in the area of the work-family interface, by including conjointly two constructs that are highlighted in studies in this area, such as work-family conflict and work-family enrichment. On the whole, the current findings also provide empirical support for the Work-Family Resources Model, which postulates that work demands and contextual resources influence family outcomes and that personal resources act as mediators in these relationships. The model also argues that macro (cultural) resources influence the relationships of the demands and the contextual resources of the work with the personal resources.

Practical Implications

The results of this research permit the elaboration of suggestions and strategies that can be implemented, aiming to reinforce the levels of flourishing in Brazilian workers. Considering that the demands of work tend to exhaust the individual and lower his levels of well-being in the family, while the social support of the supervisor and co-workers tends to reinvigorate him and increase his level of family well-being, the organizational management policies need to adopt interventions designed to curb excessive work demands and to encourage the social support provided by supervisors and co-workers.

The results reported here demonstrate that work may be able to improve family relationships, even in this context is more intimate. For example, the supervisor can adopt some strategies to support his employee: issuing frank and clear communication; feedback management; making yourself available for any intercurrence, be it professional or personal; being attentive and aware of the problems and commitments of the employee (work and family); guide and share ideas that help employees to better reconcile work and family, provide more flexible schedules for the care of children and the elderly, services for referring employees' children to kindergartens and kindergartens, daycare centers in the workplace or daycare assistance, offering courses and training to help employees deal with the most frequent conflicts at work and in the family. With all this support in his work, the subject will be able to better reconcile his work with his family, which may result in an improvement in his family relationships.

Also considering that the organizational culture associated with employees' values of satisfaction and well-being weakens the impact of work demands and enhances the influence of social support on positive psychological capacities and that these abilities are associated with the level of well-being, it would be essential for managers to seek such cultural value in the organizations they operate in. This strategy is fundamental for the employees to present a positive state, which can be reflected in the achievement of their well-being, not only in the organizational context but also in their family context.

Limitations and suggestions for future studies

The research has some limitations. The first refers to the use of self-report instruments, which can generate the common method bias. Considering, however, that workers themselves have clearer ideas about their job responsibilities, their positive psychological capacities, and their family context, it would be difficult to obtain accurate information with any method other than self-report. In addition, the problem of the common method bias may have been minimized for two other reasons: one is that the respondents' anonymity was assured, as well as the fact that there were no right or wrong questions, i.e. there was no risk of personal or professional harm to the respondents. The other was that the items addressed different variables, as observed in the analysis of the measuring model, which may help avoid biased responses (Jordan & Troth, 2020).

Another limitation is related to the cross-sectional design of the study, which prevents causal inferences between variables. Future research may correct this limitation with the adoption of longitudinal designs, which will allow us to obtain a better understanding of the relationships between the variables of this research. A third limitation is related to the online data collection, without the researchers' presence, which may have generated a lack of commitment and less reliable answers. Thus, future research could be carried out with face-to-face data collection. In this study, the moderating role of macro resources only was tested, neglecting the role of key resources, as advocated by the WF-R Model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Thus, future research could further contribute to the advancement of literature in the area of the work-family interface, by also including the key resources in the models to be tested. Finally, the present study did not consider the heterogeneity of the participants (for example, in terms of the broad age ranges and length of experience, as well as the variation between the sizes of the organizations) in the analyses. Future studies could explore such peculiarities.

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI