Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Ciencias Psicológicas

Print version ISSN 1688-4094On-line version ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.1 Montevideo 2023 Epub June 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2478

Original Articles

Interventions to improve mentalization and reflective functioning: a scoping review

1 Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brasil, marcialavarda@gmail.com

2Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brasil

3Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brasil

This scoping review explores research conducted between 2008 to 2019, that aims to understand the conceptual use of mentalization (M) and reflective functioning (RF) and explore possibilities for interventions that promote these skills. The review utilized the descriptors “reflective functioning OR mentalizing OR mentalization AND intervention”. Reviewed papers were written in English, Portuguese or Spanish, and covered several research areas. The analysis considered several categories, including aims, study design, participants, type of intervention, intervention assessments and outcomes. Thirty-four papers were considered, most of them using a quantitative approach and addressed to adults and parents/caregivers-infants. The present review highlights the need to develop specific assessments procedures to evaluate RF and M, as well as studies that consider the Brazilian context. The study also emphasizes the need for theoretical systematization of M and RF concepts, considering they are frequently used as synonyms.

Keywords: mentalization; intervention; reflective functioning

Esta revisão integrativa da literatura objetivou sistematizar as possibilidades de intervenções promotoras da Capacidade de Mentalização (CM) e Função Reflexiva (FR), publicadas entre 2008 a 2019. Utilizou-se os descritores “reflective functioning OR mentalizing OR mentalization AND intervention” e incluiu-se artigos empíricos, disponibilizados em Inglês, Português ou Espanhol, provenientes de diferentes áreas. Analisou-se os dados através das categorias: objetivos; delineamentos; participantes; tipo de intervenção utilizada; instrumentos de avaliação da intervenção empregados; resultados. Encontrou-se 34 artigos que predominantemente verificaram a eficácia das intervenções, possuíam delineamento quantitativo, voltados para adultos e, ainda, intervenções com potencial para fortalecer os vínculos pais/cuidadores-criança. Concluiu-se sobre a necessidade de se desenvolver instrumentos específicos para avaliar FR e CM, estudos que abordem a realidade brasileira e, ainda, a sistematização desses conceitos, que na maioria dos artigos, se apresentaram como sinônimos.

Palavras-chave: mentalização; intervenção; função reflexiva

La presente revisión integrativa exploró investigaciones realizadas entre 2008 y 2019 para sistematizar información acerca del uso conceptual de capacidad de mentalización (CM) y función reflexiva (FR), así como las posibilidades de intervenciones para su promoción. Los descriptores fueron “reflective functioning OR mentalizing OR mentalization AND intervention” en la búsqueda artículos empíricos en inglés, portugués o español, de distintas áreas del conocimiento. El análisis de los datos consideró las categorías: objetivos, diseños, participantes, tipo de intervención utilizada, instrumentos de evaluación de la intervención y resultados. Treinta y cuatro artículos fueron elegidos, en su mayoría cuantitativos, destinados a adultos y padres-bebés. La revisión destaca la necesidad del desarrollo de instrumentos de evaluación específicos para evaluar FR y CM, así como la necesidad de investigaciones que exploren la realidad de países como Brasil. Otro aspecto es la sistematización de los conceptos, ya que, en su mayoría, fueron referidos como sinónimos.

Palabras clave: mentalización; intervención; función reflexiva

Studies focused on parent-infant interactions and their repercussions on the formation of the infant psyche suggest that early interactions are crucial for the infant's psychological development and have a strong influence on infants’ emotional health, on the formation of later social relationships and on problem-solving ability (Akhtar, 2007). Empirical evidence supports a link between the affective experiences during the first years of life and the incidence of biopsychosocial disorders, such as affective and anxiety disorders, chronic stress, and psychosocial difficulties (Lecannelier, 2006).

The infant, equipped with an incipient psychic apparatus, forms their psyche through unconscious communication established with their mother, using the maternal psychism as an auxiliary ego to navigate the real world (Cramer & Palacio-Espasa, 1993). In this way, the inheritance of maternal experiences of real and fantasized relationships with parental figures may interfere in the mother-infant interaction, facilitating or hindering the creation of a healthy bond (Feliciano & Souza, 2011). Recent investigations, based on studies primarily conducted in the 1990s (Fonagy & Target, 1997), have recognized the crucial role of mentalization (M) and reflective functioning (RF) in attachment relationships between parents and their children (Tomlin et al., 2009), specially related to infant’s emotion regulation process and in the development of a secure attachment (Slade, 2005), which reverberate throughout the life.

The mentalization theory, developed by Fonagy and colleagues in the 1990s (Holmes, 2006) is based on the theory of mind, attachment theory, developmental psychopathology, cognitive psychology as well as neuroscience. It encompasses the concepts of mentalization and reflective functioning. Mentalization is defined as an imaginative capacity and a transactional social process (Fonagy & Target, 1997), understood as the ability to understand oneself and others in terms of underlying processes and mental states, such as feelings, desires and beliefs (Fonagy & Allison, 2012). Reflective functioning, on the other hand, is a manifestation of mentalization, and refers to an individual’s ability to mentalize their own mental states, as well as those of others (Slade, 2005). In the context of parent/caregiver-infant relationships, the adult's ability to reflect infant’s internal states through consistent responses to infant’s internal state and emotions rather than parental projections, is called parental reflective functioning (PRF) (Ramires & Godinho, 2011). The concept of Parental Reflective Functioning (PRF) was introduced by Slade (2005). Higher PRF predicts greater parental ability to deal with infant's emotional lability, without being dominated by their own emotions (Kelly et al., 2005).

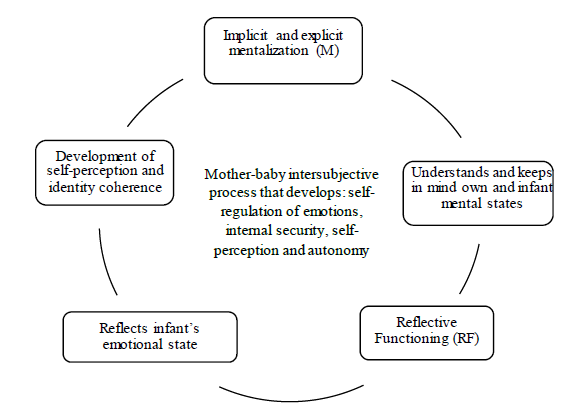

The maternal condition to keep in mind the representation of the infant as someone with feelings, desires, and intentions will allow the mother to mirror and re-present infant’s affective state, enabling the infant to discover their own internal experience (Slade, 2005). This process provides the creation of a positive bond and a physical and psychological experience of security for the infant, playing a vital role in the transgenerational transmission of attachment (Ordway et al., 2015).

This unique and significant bond between infant and the attachment figure generates a sense of security in the infant, arising from maternal availability and sensitivity. This sense of security will be essential for the strengthening of the dyadic relationship and for the development of a secure base during infant’s explorations (Bowlby, 1989; Dalbem & Dalbosco, 2005). In a secure attachment relationship, parents respond to child's emotional states in a welcoming and meaningful way through their FR, which allows the child to understand and differentiate their mental states and emotions, developing a perception of themselves and their own mentalization (Ensink et al., 2015; Fonagy & Target, 2006; Zevalkink, 2008).

The acquisition of mentalization integrates an intersubjective process between parents/caregiver-infant which enable the achievement of infant’s emotion self-regulation, being important for the development of their internal security, self-esteem and autonomy (Fonagy, 1999; Ramires & Schneider, 2010). In this sense, based on the understanding that M and RF result from the association between childhood experiences and that they may be temporarily impaired in situations of great emotional impact, impacting on the mother-baby relationship, the latter's emotional development (Mesa & Gómez, 2010) and the quality of social interactions throughout life, it becomes essential to investigate interventions capable of improving and promoting these skills. Therefore, this study aimed to discuss the interventions focused on the improvement and promotion of M and RF, published between 2008 and 2019. Also, considering the number of studies using the terms M and RF as synonyms (Dalbem & Dalbosco, 2005), a conceptual systematization from the existing literature is also important.

Method

The review presented herein was motivated by the following question: What are the interventions carried out in the recent years focused on the improvement or promotion of mentalization and/or reflective functioning? Seven data bases from psychology, medicine and nursing were searched (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Medline Complete, Scopus, PsycINFO, LILACS and SciELO) during the month of May 2020, using the combined descriptors: “reflective functioning OR mentalizing OR mentalization AND intervention”.

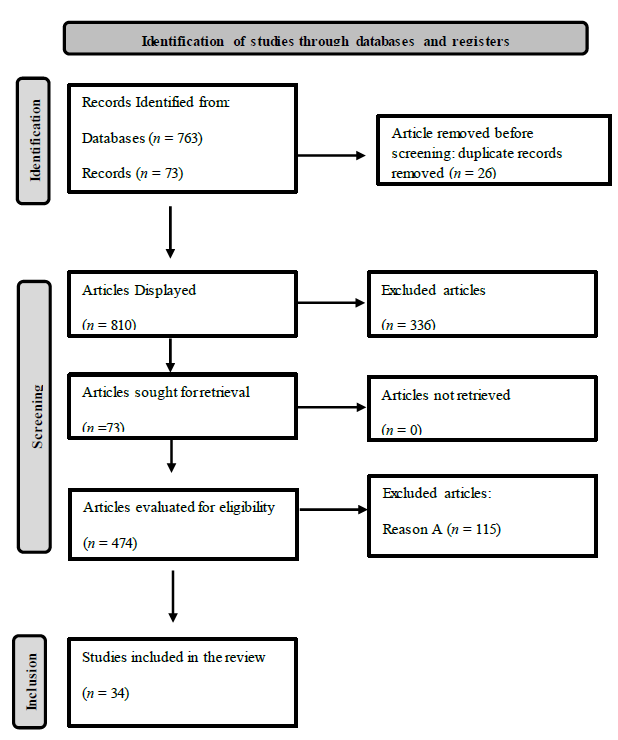

The following inclusion criteria were adopted: (a) be an empirical article, thesis, or dissertation; (b) have been published between May 2008 and December 2019; (c) the material is available in its entirety; and (d) material available in English, Portuguese or Spanish. As exclusion criteria it were stablished: (a) published in book format, book chapter, reviews, theoretical articles, experience reports, case studies and systematic or literature reviews; (b) publications not related to mentalization-based interventions. Moreover, the following filters were applied: a) year of publication, b) scientific paper, and c) peer-reviewed paper. The selection was made according to Figure 1, considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The majority of excluded publications were not related to interventions, focused on brain functioning, biology of insects, such as corneal structures and the understanding of optical diffraction. To reduce possible biases and ensure the quality of the findings, two independent judges carried out the procedures. The guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., 2009; Prisma <www.prisma-statement.org/>) were applied. Aiming to carry out a global analysis of the results, the publications which met the inclusion criteria were quantitatively analyzed. A qualitative analysis was also applied to explore the content.

Results and Discussion

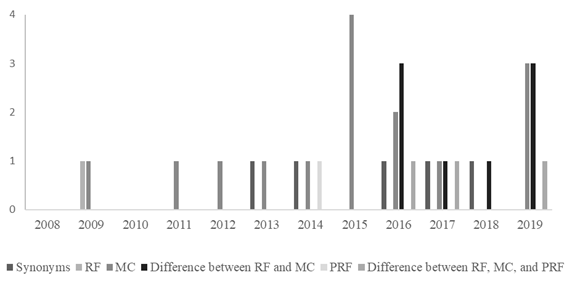

No publications were found based on the searched descriptors between 2008 and 2010, The first publications were retrieved in 2009, with two publications (Fonagy et al., 2009; Vik & Hafting, 2009), same rates as in 2018 (De Meulemeester et al., 2018; Ordway et al., 2018). Since 2013 the number of publications on the topic has been increasing. The highest incidence of publications reporting interventions focused on mentalization and reflective functioning was observed during 2016 and 2019, with seven publications found in each year (Ashton et al., 2016; Barnicot & Crawford, 2019; Bateman et al., 2016; Einy et al., 2019; Enav et al., 2019; Esposito et al., 2019; Griffiths et al., 2019; Hertzmann et al., 2016; Kivity et al., 2019; Meschino et al., 2016; Pajulo et al., 2016; Stacks et al., 2019; Suchman et al., 2016; Ware et al., 2016). During 2015 and 2017 four publications were found in each year (Bo et al. al., 2017; Bressi et al., 2017; Edel et al., 2017; Freda et al., 2015; Howieson & Priddis, 2015; Rice et al., 2015; Rosenblau et al., 2015; Suchman et al., 2017). In 2013 and 2014 three publications were found in each year (Bain, 2014; Ensink et al., 2013; Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, 2013; Ordway et al., 2014; Ramsauer et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013). In 2011 and 2012 just one publication was found in each year (Jakobsen et al., 2012; Twemlow et al. 2011).

The distribution of publications per year reflects the evolution of research in the field of mentalization theory, carried out by Fonagy and collaborators since the 90s (Holmes, 2006; Slade, 2007). Moreover, the creation of specific study groups dedicated to the development of intervention programs for parents and younger children in a high-risk environment (Slade, 2007), may also contributed with the increasing of the research.

Upon analyzing the concepts of M and RF throughout the review, it was observed, as shown in Figure 2, that these terms emerged in the literature in 2009, with mentalization being the predominant concept explored until 2015. These findings are consistent with a study that reported a significant increase in the use of the term mentalization between 1991 and 2017, which went from 7 to 844, according to the Thompson Reuter searcher - Web of Science (Malda-Castillo et al., 2019).

Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, since 2013 theoretical articulations among the differences between M and RF have been observed, with a peak in 2016. As for RF, even though it was not present in the theoretical body of scientific studies, it was treated by several researchers as a synonym of M from 2013, leading to an indiscriminate use of both terms. The terms were defined as being the perception of oneself and others as psychological subjects, considering thoughts, feelings, intentions, desires and motivations implicit in behavior (Ensink et al., 2015).

Therefore, it can be seen that RF has been mentioned, in many studies, as an instrument for analyzing M, being reported as an observable and measurable manifestation of M (Bain, 2014; Bateman et al., 2016; Bo et al., 2017; De Meulemeester et al., 2018; Pajulo et al., 2016; Ramsauer et al., 2014). This may have been generated from the initial understanding that M entails a reflexive and introspective behavior that enables an individual to recognize both their own and others intentional and underlying mental states. However, it should be noted that M and RF are distinct concepts, and despite recent literature highlighting the differences between the concepts, they are still being treated as synonyms in some of recent studies, indicating the need for a theoretical consolidation.

The findings of this review were examined according to the following categories: 1) Aims, 2) Study design, 3) Participants, 4) Type of intervention, 5) Intervention assessments, and 6) Outcomes. Considering the category 1) Aims, two subcategories were explored: 1a) studies focused on describing and exploring the results of the applied intervention; and 1b) studies focused on the intervention efficacy.

The subcategory 1a stands out, comprising twenty-one of the publications which explored the effect of the interventions, such as Creating a Peaceful School Learning Environment (CAPSLE), a manual-based antiviolence program/mentalization-based intervention, a manualized School Psychiatric Consultation (SPC) and treatment-as-usual (TAU), in reducing aggression and victimization among elementary school students (Fonagy et al., 2009). Another study, focused on patients with major depressive disorder, compared the effects of third-wave cognitive therapy versus Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT; Jakobsen et al., 2012). Still in subcategory 1a, (n = 18) of studies aimed to describe the interventions and explore their results.

Some of them were implemented in various settings, such as schools (Twemlow et al., 2011); forensic contexts (Ware et al., 2016); with novice therapists (Ensink et al., 2013); group therapy with adolescents with borderline personality disorder (Bo et al., 2017) and with children who are adopted or in the process of adoption (Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, 2013). Other interventions took place in hospitals, with pregnant women using substances (Pajulo et al., 2016) and mothers diagnosed with postpartum depression (Vik & Hafting, 2009); in a clinical context comparing implicit and explicit mentalization processes in individuals diagnosed with Autism (Rosenblau et al., 2015); in a family context focusing on mediation programs (Howieson & Priddis, 2015) and finally, interventions targeting mothers and fathers that explored PRF (Ashton et al., 2016; Enav et al., 2019; Ordway et al., 2014; Ordway et al., 2018; Stacks et al., 2019).

The subcategory 1b identified thirteen studies, which aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions (Bain, 2014; Bateman et al., 2016; Bressi et al., 2017; De Meulemeester et al., 2018; Freda et al., 2015; Griffiths et al., 2019; Hertzmann et al., 2016; Meschino et al., 2016; Ramsauer et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2015; Sadler et al., 2013; Suchman et al.., 2017; Suchman et al., 2016). Six of them were focused on M and PRF (Bain, 2014; Meschino et al., 2016; Ramsauer et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013; Suchman et al., 2017; Suchman et al., 2016).Considering these data, despite most studies (n = 18) have been dedicated to the description and evaluation of interventions, a large portion of the studies (n = 13) have evaluated the effectiveness of interventions focused on RF and M in different populations and contexts, denoting a search for more evidence-based practices in the field (Melnik et al., 2014).

The category 2) Study design was divided into three subcategories: 2a) quantitative studies; 2b) qualitative studies; and 2c) mixed-methods studies. The 2a stands out, covering 29 studies, most of them focused on randomized control trials (RCT) and pilot studies. Only five of them performed follow-ups (Bressi et al., 2017; Einy et al., 2019; Enav et al., 2019; Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, 2013; Ordway et al., 2014). Only three studies were included in the subcategory 2b. All of them using a qualitative design (Ordway et al., 2018; Vik & Hafting, 2009; Ware et al., 2016). Subcategory 2c counted with 2 mixed-methods studies (Hertzmann et al., 2016; Howieson & Priddis, 2015). It was observed a tendency to carry out quantitative investigations and, in particular, RCT, since this type of clinical trial has a low incidence of bias, being considered the gold standard procedure to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments (Leonardi, 2017).

The predominant choice of a controlled and evidence-based design is in line with the study aims, most of them focused on the evaluation of intervention’s effectiveness, since RCT and meta-analyses have been considered important methods to evaluate interventions efficacy and effectiveness (Baptista, 2010). Moreover, the follow-up strategy, which is recommended in efficacy and effectiveness studies to assess the maintenance of results after the end of the intervention, was not applied in most studies, which was also reported in the studies conducted by Volkert et al. (2019) and Malda-Castillo et al. (2019), where most of the reviewed studies did not do or did not report the follow-up procedure.

Regarding a small range of publications using a qualitative approach, it should be noted that qualitative studies may be consider in future research, since they allow the exploration and implementation of new interventions, as well as the identification of procedures that can be effective in a clinical context (Leonardi, 2017).

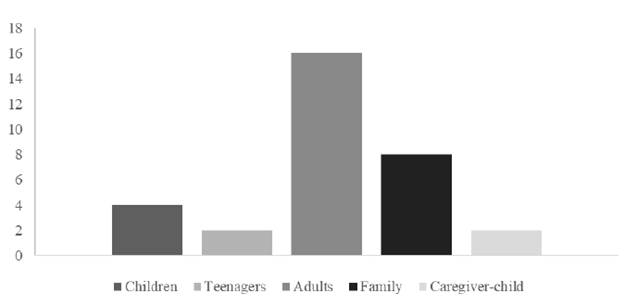

Related to category 3) Participants, it refers to the target population, and it was divided into five subcategories: 3a) children; 3b) teenagers; 3c) adults; 3d) family; and 3e) caregiver-child. The subcategory 3c had a total of 17 studies (Barnicot & Crawford, 2019; Bateman et al., 2016; Bressi et al., 2017; De Meulemeester et al., 2018; Edel et al., 2017; Einy et al., 2019; Ensink et al., 2013; Esposito et al., 2019; Freda et al., 2015; Jakobsen et al., 2012; Kivity et al., 2019; Pajulo et al., 2016; Rosenblau et al., 2015; Suchman et al., 2017; Vik & Hafting, 2009; Ware et al., 2016), with the others distributed as shown in Figure 3.

The emphasis on having the adults as the main participants of the studies may be related to the initial work of Fonagy and collaborators, when developing the MBT, which was originally focused on patients with borderline personality disorder, information that can be corroborated by a review conducted by Volkert et al. (2019), which explored mentalization-based treatments for patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. The study pointed out that adolescent population was less prevalent in the reviewed studies. The participation of families in the studies, however, denotes the expansion of the application of the concepts of RF and M to the scope of parents-child relationships.

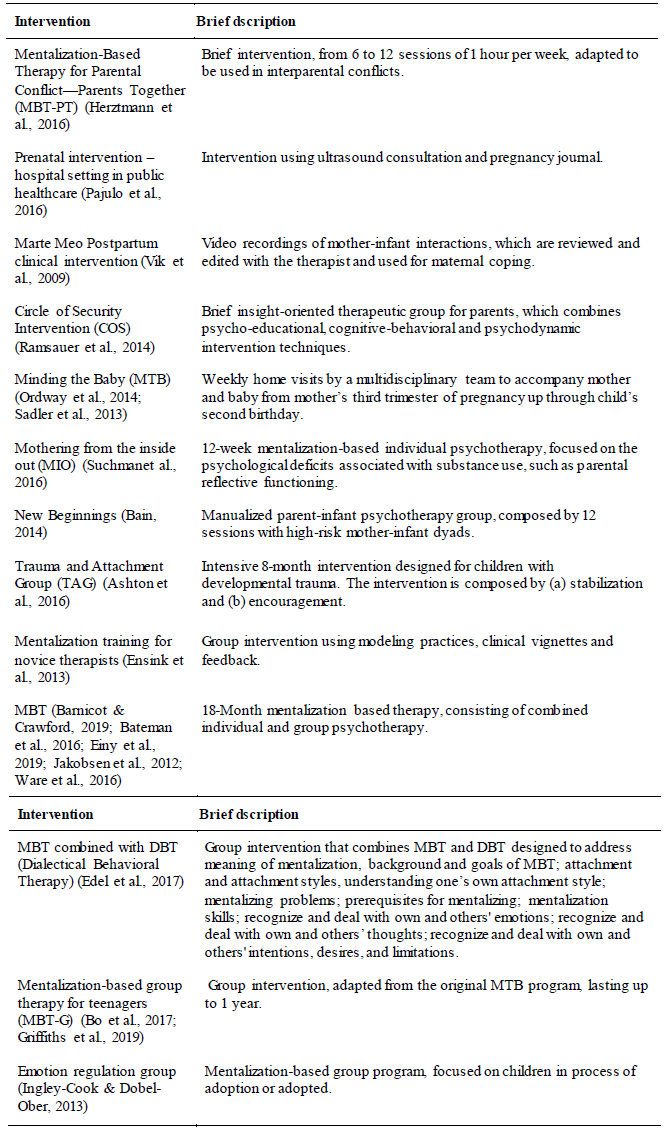

The category 4) Type of intervention was divided into two subcategories: 4a) interventions in a clinical context (applied in clinics, which follow the standard setting of psychotherapies) and 4b) interventions in other contexts (applied in different contexts that do not follow the standard setting of psychotherapies). The category 4b) comprises twenty studies (Bain, 2014; De Meulemeester et al., 2018; Edel et al., 2017; Ensink et al., 2013; Esposito et al. al., 2019; Fonagy et al., 2009; Freda et al., 2015; Howieson & Priddis, 2015; Ordway et al., 2014; Ordway et al., 2018; Pajulo et al., 2016; Rice et al. , 2015; Rosenblau et al., 2015; Sadler et al., 2013; Stacks et al., 2019; Suchman et al., 2016; Suchman et al., 2017; Twemlow et al., 2011; Vik & Haftig, 2009; Ware et al., 2016). On the other hand, category 4a), which compiled the interventions in clinical settings, counted with nine studies (Ashton et al., 2016; Bateman et al., 2016; Bo et al., 2017; Bressi et al., 2017; Hertzmann et al., 2016; Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, 2013; Jakobsen et al., 2012; Meschino et al., 2016; Ramsauer, 2014). Table 1 shows some examples of interventions cited more frequently and which have not yet been portrayed in this writing.

There is a diversity of interventions that can be applied to develop M and RF, and in the last 5 years it was observed an increase of studies about programs focusing on PRF. MBT is the most prevalent intervention among the interventions which stand out in this review, possibly because Fonagy and collaborators seek to investigate evidence of its efficacy and effectiveness. Therefore, MBT has been serving as inspiration for other proposals, which use its theoretical and technical principles. Moreover, most of the reviewed interventions focused on the treatment of psychopathologies, such as borderline personality disorder, autism spectrum disorders and major depressive disorder, and were applied in different contexts, such as clinical, school, hospital and community.

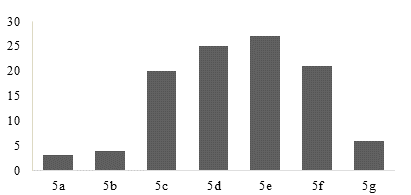

The category 5) Intervention assessments, is related to the measures used to evaluate the interventions. A range of instruments was observed (n = 107). The instruments used assessed different indicators of change, requiring the creation of subcategories for better exploration. Thus, the following subcategories were developed: 5a) family sociodemographic data collection; 5b) evaluation of the therapeutic alliance (TA) and countertransference (CT) of the participants towards the intervention; 5c) to measure RF and M; 5d) to measure symptomatology of the participants; 5e) Mother-child interaction; 5f) Functioning and global development of the participants; 5g) Specific evaluation of the intervention. The total number of instruments obtained are shown in Figure 4.

In this sense, subcategory 5e concentrated 27 instruments focused on capturing maternal sensitivity, attachment patterns, social adjustment and the type of interaction of mother-infant dyad. Among the 27 instruments found, the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) was the most used (n = 3) (Ramsauer et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013; Suchman et al., 2017), followed by sessions of mother-child free play (n = 2) (Ordway et al., 2018; Suchman et al., 2016).

In the subcategory 5d, twenty-five instruments assessed maternal mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, stress, alexithymia, and borderline personality. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) stands out here, being applied in five studies (Bateman et al., 2016; Bo et al., 2017; Edel et al., 2017; Jakobsen et al., 2012; Ramsauer et al., 2014). In subcategories 5c and 5f, with twenty and twenty-one instruments each, the use of the Parental Development Interview (PDI) stands out (Enav et al., 2019; Hertzmann et al., 2016; Ordway et al., 2016; Sadler et al., 2013; Suchman et al., 2017), as well as the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (PRFQ; Ashton et al., 2016; Hertzmann et al., 2016; Pajulo et al., 2016; Ramsauer et al., 2014).

The subcategory 5g, which encompasses six instruments, focused on a range of interviews to assess interventions (Hertzmann et al., 2016; Howieson & Priddis, 2015; Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, 2013; Meschino et al., 2016; Vik & Hafting, 2009; Ware et al., 2016). Finally, the subcategories 5a and 5b, with 3 and 4 instruments each, with semi-structured interviews reported twice on the subcategory 5a (n = 2) (Ordway et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013). In the subcategory 5b, the measures applied were the Working Alliance Inventory-Revised (Sadler et al., 2013), the Parenting Alliance Measure (PAM; Hertzmann, 2016), the Countertransference Rating Scale (CRS; Ensink et al., 2013) and the Psychotherapy Q-Sort (Kivity et al., 2019).

Considering that mentalization theory has been explored and implemented in recent decades, it was observed few instruments used to assess the intervention, with only one instrument developed for this purpose. The Revised MIO/PE Adherence Rating Scale (Sadler et al., 2013; Suchman et al., 2017), was the only instrument reported on the studies to evaluate the efficacy of the program Mothering from the Inside Out (MIO). This statement may be responsible for a variability of measures found, which are used in the evaluation of different indicators of change which guided the discussions related to intervention’s outcomes. According to Baptista (2010), despite limitations in the field of studies on evidence of effectiveness in psychotherapeutic processes, it is possible to establish assessment protocols and accurate procedures, such as meta-analysis.

The category 6) Outcomes, highlighted that the proposed interventions, mostly, have showed satisfactory outcomes, (n = 23) (Bain, 2014; Bateman et al., 2016; Edel et al., 2017; Enav et al., 2019; Ensink et al. al., 2013; Einy et al., 2019; Fonagy et al., 2009; Freda et al., 2015; Griffiths et al., 2019; Howieson & Priddis, 2015; Kivity et al., 2019; Ordway et al., 2018; Rosenblau et al. , 2015; Rice et al., 2015; Ware et al., 2016; Sadler et al., 2013; Stacks et al., 2019; Suchman et al., 2016; Suchman et al., 2017; Twemlow et al., 2011; Vik & Hafting, 2009). Among them, interventions based on MBT have been effective, decreasing symptoms severity in patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder (Bateman et al., 2016; De Meulemeester et al., 2018; Edel et al., 2017; Einy et al., 2019). Improvement on emotion regulation, behavior (Ware et al., 2016), as well as in mentalization and attachment patterns established between peers (Bo et al., 2017) were also observed.

MBT, when combined with Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), achieved even more satisfactory results in reducing insecure attachment and improving mentalization in patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (Edel et al., 2017). Both approaches prioritize the creation of a secure relationship in therapy, the use of empathy and validation in reciprocal relationship, the strengthening of patient's capacities to reduce impulsive behaviors, as well as the increase of self-awareness (Swenson & Choi-Kain, 2015).

On the other hand, a study conducted by Jakobsen et al. (2012) pointed out that third-wave cognitive therapy may be more effective than MBT in addressing depressive symptoms. Similarly pointed out the study of Barnicot and Crawford (2019), especially regarding the reduction of self-injurious behaviors over time. However, it is suggested investments in RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of different approaches. Furthermore, it should be noted that studies focused on the evaluation of DBT effectiveness have been more prevalent in the last decade.

Conclusions

It is noteworthy that the terms mentalization and reflective functioning are relatively new in psychology and have been explored extensively in recent decades, with a large number of publications in 2016. While these constructs are related, they have particularities that should be considered in further studies. Reflective functioning has been presented in some studies as being equivalent to mentalization, resulting in instruments that assess RF being used to measure mentalization. This finding highlights a lack of measures to evaluate mentalization and reflective functioning separately.

On the other hand, as research progresses into different contexts, an important differentiation between mentalization and reflective functioning has emerged. It is suggested that the literature consider the interdependence between mentalization and reflective functioning, as illustrated in Figure 5. This is because an individual may demonstrate adequate mentalization but experience difficulties with their reflective functioning, while the opposite may not necessarily be true.

Although most of the research evaluated in this study aimed to verify the effectiveness of interventions focused on mentalization and reflective functioning, possibly expressing a movement aimed at evaluating outcomes to consolidate proposals related to the theme and the need to build evidence-based practices, it is understood that regarding quantitative studies, it is now required for researchers to return to the specificities of the proposals, as well as their scope in different contexts through qualitative or mixed-methods designs.

Faced with interventions that used MBT, it is suggested that RCT be further explored. Another important point is carried out studies with follow-up, which may contribute to the evaluation of evidence-based treatments, as well as to identify possible changes in interventions over time.

Considering that the outcomes of the studies pointed out that interventions focused on mentalization and reflective functioning have the potential to contribute to the establishment of a secure attachment, it is crucial to expand intervention programs in different contexts, targeting different populations, such as parent/caregiver-child dyads and triads, as well as different ethnic groups. Moreover, there is a need to develop measures to assess mentalization and reflective functioning and report interventions in other countries, such as countries from Latin America are needed.

As limitations of this review, the non-inclusion of research conducted in Brazil should be noted. Although some studies have been published, the use of keywords not indexed in the publications or the unavailability of some papers in databases at the time of the query may have result in the failure to find these publications.

REFERENCES

Akhtar, S. (2007). Primeiros relacionamentos e sua internalização. Em E. Person, A.M. Cooper & G. Gabbard (Eds.), Compêndio de Psicanálise (pp. 54-66). Artmed. [ Links ]

Ashton, C. K., O’Brien-Langer, A., & Silverstone, P. H. (2016). The CASA Trauma and Attachment Group (TAG) Program for children who have attachment issues following early developmental trauma. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(1), 35-42. [ Links ]

Bain, K. (2014). “New beginnings” in South African shelters for the homeless: piloting of a group psychotherapy intervention for high‐risk mother-infant dyads. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 591-603. http://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21457 [ Links ]

Baptista, M. N. (2010). Questões sobre avaliação de processos psicoterápicos. Revista Psicologia em Pesquisa, 4(2). [ Links ]

Barnicot, K. & Crawford, M. (2019). Dialectical behaviour therapy v. mentalisation-based therapy for borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 49(12), 2060-2068. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002878 [ Links ]

Bateman, A., O’Connell, J., Lorenzini, N., Gardner, T., & Fonagy, P. (2016). A randomised controlled trial of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 304. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1000-9 [ Links ]

Bo, S., Sharp, C., Beck, E., Pedersen, J., Gondan, M., & Simonsen, E. (2017). First empirical evaluation of outcomes for mentalization-based group therapy for adolescents with BPD. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(4), 396. http://doi.org/10.1037/per0000210 [ Links ]

Bowlby, J. (1989). Uma base segura. Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Bressi, C., Fronza, S., Minacapelli, E., Nocito, E. P., Dipasquale, E., Magri, L., Lionetti, F., & Barone, L. (2017). Short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapy with mentalization‐based techniques in major depressive disorder patients: relationship among alexithymia, reflective functioning, and outcome variables-a pilot study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: theory, research and practice, 90(3), 299-313. http://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12110 [ Links ]

Cramer, B. & Palacio-Espasa, F.(1993). Técnicas psicoterápicas mãe/bebê. Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Dalbem, J. X. & Dalbosco, D. D. (2005). Teoria do apego: bases conceituais e desenvolvimento dos modelos internos de funcionamento. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 57(1), 12-24. [ Links ]

De Meulemeester, C., Vansteelandt, K., Luyten, P., & Lowyck, B. (2018). Mentalizing as a mechanism of change in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a parallel process growth modeling approach. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(1), 22. http://doi.org/10.1037/per0000256 [ Links ]

Edel, M. A., Raaff, V., Dimaggio, G., Buchheim, A., & Brüne, M. (2017). Exploring the effectiveness of combined mentalization‐based group therapy and dialectical behaviour therapy for inpatients with borderline personality disorder-A pilot study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(1), 1-15. http://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12123 [ Links ]

Einy, S., Narimani, M., & Sadeghi-Movahhed, F. (2019). Comparing the effectiveness of mentalization-based therapy and cognitive-analytic therapy on ego strength and defense mechanisms in people with Borderline Personality Disorder. Quarterly of the Horizon of Medical Sciences, 25(4), 324-339. http://doi.org// 10.32598/hms.25.4.324 [ Links ]

Enav, Y., Erhard-Weiss, D; Kopelman, M; Samson, A. C; Mehta, S; Gross, J. J., & Hardan, A. Y., (2019). A non randomized mentalization intervention for parents of children with autism. Autism Research, 12(7), 1077-1086. http://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2108 [ Links ]

Ensink, K., Fonagy, P., Normandin, L., Berthelot, N., & Biberdzic, M. (2015). O papel protetor da mentalização de experiências traumáticas: implicações quando da entrada na parentalidade. Estilos Clínicos, 20(1), 76-91. http://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1981-1624.v20ilp76-91 [ Links ]

Ensink, K., Maheux, J., Normandin, L., Sabourin, S., Diguer, L., Berthelot, N., & Parent, K. (2013). The impact of mentalization training on the reflective function of novice therapists: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 23(5), 526-538. http://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.800950 [ Links ]

Esposito, G., Karterud, S., & Freda, M. F. (2019). Mentalizing underachievement in group counseling: Analyzing the relationship between members' reflective functioning and counselors' interventions. Psychological Services, 18(1), 73-83. http://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000350 [ Links ]

Feliciano, D. de S. & Souza, A. S. L. (2011). Para além do seio: uma proposta de intervenção psicanalítica pais-bebê a partir de dificuldades na amamentação. Jornal de Psicanálise,44(81), 145-161. [ Links ]

Fonagy, P. & Allison, E. (2012). What is mentalization? The concept and its foundations in developmental research. Em N. Midgley & I. Vrouva, Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 11-34). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Fonagy, P. & Target, M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: their role in self-organization. Development & Psychopathology, 9(04), 679-700. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579497001399 [ Links ]

Fonagy, P. & Target, M. (2006). The mentalization-focused approach to self pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(6), 544-576. http://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2006.20.6.544 [ Links ]

Fonagy, P. (1999). Persistencias transgeneracionales del apego: una nueva teoria. Aperturas Psicoanaliticas, 3, 1-17. [ Links ]

Fonagy, P., Twemlow, S. W., Vernberg, E. M., Nelson, J. M., Dill, E. J., Little, T. D., & Sargent, J. A. (2009). A cluster randomized controlled trial of child‐focused psychiatric consultation and a school systems‐focused intervention to reduce aggression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 607-616. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02025.x [ Links ]

Freda, M. F., Esposito, G., & Quaranta, T. (2015). Promoting mentalization in clinical psychology at universities: A linguistic analysis of student accounts. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 11(1), 34. http://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i1.812 [ Links ]

Griffiths, H., Duffy, F., Duffy, L., Brown, S., Hockaday, H., Eliasson, E., Graham, J., Smith, J., Thomson, A., & Schwannauer, M. (2019). Efficacy of mentalization-based group therapy for adolescents: the results of a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 167-180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2158-8 [ Links ]

Hertzmann, L., Target, M., Hewison, D., Casey, P., Fearon, P., & Lassri, D. (2016). Mentalization-based therapy for parents in entrenched conflict: a random allocation feasibility study. Psychotherapy, 53(4), 388. http://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000092 [ Links ]

Holmes, J.(2006). Mentalizing from a psychoanalytic perspective: What’s new? Em J. Allen & P. Fonagy (Eds.), The Handbook of Mentalization Based Treatment (pp. 31-50). John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Howieson, J. & Priddis, L. (2015). A Mentalizing‐based approach to family mediation: harnessing our fundamental capacity to resolve conflict and building an evidence‐based practice for the field. Family court review, 53(1), 79-95. http://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12132 [ Links ]

Ingley‐Cook, G. & Dobel‐Ober, D.(2013). Innovations in practice: group work with children who are in care or who are adopted: lessons learnt. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(4), 251-254. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00683.x [ Links ]

Jakobsen, J. C., Gluud, C., Kongerslev, M., Larsen, K. A., Sørensen, P., Winkel, P., Lange, T., Sogaard, U., & Simonsen, E. (2012). Third wave’cognitive therapy versus mentalization-based therapy for major depressive disorder: a protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 232. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-232 [ Links ]

Kelly, K., Slade, A., & Grienenberger, J. F. (2005). Maternal reflective functioning, mother-infant affective communication, and infant attachment: exploring the link between mental states and observed caregiving behavior in the intergenerational transmission of attachment. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 299-311. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245963 [ Links ]

Kivity, Y., Levy, K.N., Wasserman, R.H., Beeney, J.E., Meehan, K.B., & Clarkin, J.F. (2019). Conformity to prototypical therapeutic principles and its relation with change in reflective functioning in three treatments for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(11), 975-988. http://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000445 [ Links ]

Lecannelier, F. (2006). Estrategias de intervención temprana en salud mental. Revista Psicología & Sociedad, 1-9. [ Links ]

Leonardi, J. L. (2017). Métodos de pesquisa para o estabelecimento da eficácia das psicoterapias. Interação em Psicologia, 21(3), 176-186. http://doi.org/10.5380/psi.v2li3.54757 [ Links ]

Malda-Castillo, J., Browne, C., & Perez-Algorta, G. (2019). Mentalization-based treatment and its evidence-base status: A systematic literature review. Psychology and Psychotherapy : theory, research and practice, 92(4), 465-498. http://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12195 [ Links ]

Melnik, T., Fernandes de Souza, W., & Regine de Carvalho, M. (2014). A importância da prática da psicologia baseada em evidências: aspectos conceituais, níveis de evidência, mitos e resistências. Revista Costarricense de Psicología, 33(2), 79-92. [ Links ]

Mesa, A. M. & Gómez, A. C. (2010). La mentalización como estrategia para promover la salud mental en bebés prematuros. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 8(2), 835-848. [ Links ]

Meschino, D. de C., Philipp, D., Israel, A., & Vigod, S. (2016). Maternal-infant mental health: postpartum group intervention. Archives of women's mental health, 19(2), 243-251. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0551-y [ Links ]

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine, 151(4), 264-269. http://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [ Links ]

Ordway, M. R., McMahon, T. J., Kuhn, L. de L. H., & Suchman, N. E. (2018). Implementation of an evidenced‐based parenting program in a community mental health setting. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(1), 92-105. http://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21691 [ Links ]

Ordway, M. R., Sadler, L. S., Dixon, J., Close, N., Mayes, L., & Slade, A. (2014). Lasting effects of an interdisciplinary home visiting program on child behavior: Preliminary follow-up results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(1), 3-13. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2013.04.006 [ Links ]

Ordway, M. R., Webb, D., Sadler, L. S., & Slade, A. (2015). Parental reflective functioning: an approach to enhancing parent-child relationships in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 29(4), 324-334. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.12.002 [ Links ]

Pajulo, H., Pajulo, M., Jussila, H., & Ekholm, E. (2016). Substance‐abusing pregnant women: prenatal intervention using ultrasound consultation and mentalization to enhance the mother-child relationship and reduce substance use. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(4), 317-334. http://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21574 [ Links ]

Ramires, V. R. R. & Godinho, L. R. (2011). Psicoterapia baseada na mentalização de crianças que sofreram maus-tratos. Psicologia em Estudo, 16(1), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722011000100008 [ Links ]

Ramires, V. R. R. & Schneider, M. S. (2010). Revisitando alguns conceitos da teoria do apego: comportamento versus representação? Psicologia: Teoria E Pesquisa, 26, 25-33. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722010000100004 [ Links ]

Ramsauer, B., Lotzin, A., Mühlhan, C., Romer, G., Nolte, T., Fonagy, P., & Powell, B. (2014). A randomized controlled trial comparing Circle of Security Intervention and treatment as usual as interventions to increase attachment security in infants of mentally ill mothers: Study Protocol. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 24. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-24 [ Links ]

Rice, L. M., Wall, C. A., Fogel, A., & Shic, F. (2015). Computer-assisted face processing instruction improves emotion recognition, mentalizing, and social skills in students with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2176-2186. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2380-2 [ Links ]

Rosenblau, G., Kliemann, D., Heekeren, H. R., & Dziobek, I. (2015). Approximating implicit and explicit mentalizing with two naturalistic video-based tasks in typical development and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(4), 953-965. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2249-9 [ Links ]

Sadler, L. S., Slade, A., Close, N., Webb, D. L., Simpson, T., Fennie, K., & Mayes, L. C. (2013). Minding the baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home‐visiting program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(5), 391-405. http://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21406 [ Links ]

Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: an introduction. Attachment and Human Development, 7(3), 269-281. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245906 [ Links ]

Slade, A. (2007). Reflective parenting programs: theory and development. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 26(4), 640-657. http://doi.org/10.1080/07351690701310698 [ Links ]

Stacks, A. M., Barron, C. C., & Wong, K. (2019). Infant mental health home visiting in the context of an infant-toddler court team: Changes in parental responsiveness and reflective functioning. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(4), 523-540. https://doi.org/10.1002/21785 [ Links ]

Suchman, N. E., De Coste, C. L., McMahon, T. J., Dalton, R., Mayes, L. C., & Borelli, J. (2017). Mothering from the Inside Out: Results of a second randomized clinical trial testing a mentalization-based intervention for mothers in addiction treatment. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 617-636. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000220 [ Links ]

Suchman, N. E., Ordway, M. R., de las Heras, L., & McMahon, T. J. (2016). Mothering from the Inside Out: results of a pilot study testing a mentalization-based therapy for mothers enrolled in mental health services. Attachment & Human Development, 18(6), 596-617. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2016.1226371 [ Links ]

Swenson, C. R. & Choi-Kain, M. D. (2015). Mentalization and Dialectical Behavior Therapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 69(2). 199-217. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.199 [ Links ]

Tomlin, A. M., Sturm, L., & Koch, S. M. (2009). Observe, listen, wonder, and respond: A preliminary exploration of reflective function skills in early care providers. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30(6), 634-647. http://doi.org10.1002/imhj.20233 [ Links ]

Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., Sacco, F. C., Vernberg, E., & Malcom, J. M. (2011). Reducing violence and prejudice in a Jamaican all age school using attachment and mentalization theory. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 28(4), 497. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0023610 [ Links ]

Vik, K. & Hafting, M. (2009). The outside view as facilitator of self‐reflection and vitality: A phenomenological approach. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 27(3), 287-298. http://doi.org/10.1080/02646830802409645 [ Links ]

Volkert, J., Hauschild, S., & Taubner, S. (2019). Mentalization-Based treatment for personality disorders: efficacy, effectiveness, and new developments. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(4), 21-25.http://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1012-5 [ Links ]

Ware, A., Wilson, C., Tapp, J., & Moore, E. (2016). Mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) in a high-secure hospital setting: expert by experience feedback on participation. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(5), 722-744. http://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2016.1174725 [ Links ]

Zevalkink, J. (2008). Assessment of mentalizing problems in children. In A.J.E. Verheugt-Pleiter, J. Zevalkink & M.G.C. Schmeets (Eds.), Mentalizing in children therapy (pp. 22-40). Karnac. [ Links ]

How to cite: Pinheiro Schaefer, M., Becker, D., & Donelli, T. M. S. (2023). Interventions to improve mentalization and reflective functioning: a scoping review. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2478. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2478

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M. P. S. has contributed in a, b, c, d; D. B. in c, d; T. M. S. D. in e

Received: February 26, 2021; Accepted: January 25, 2023

text in

text in