Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Ciencias Psicológicas

Print version ISSN 1688-4094On-line version ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.1 Montevideo 2023 Epub June 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2904

Original Articles

Work-family conflict, perception of gender equality and subjective well-being of health officials in the Maule Region

1 Universidad de Talca, Chile, ajimenezutalca@gmail.com

The aim of this study was to describe the relationship between work- family conflict, perception of gender equality and subjective well-being of health officials in the Maule Region (Chile). The sample used was 255 health officials from three public services of the Maule Region. The instruments used were the CTF/CFT Scale, the Gender Equity Perception Questionnaire, the Satisfaction with Life Scale and the Subjective Happiness Scale. It was observed that the direction of work-family conflict is predominantly from family to work. In the same way, it was found that there is a statistically significant and negative relationship between the work-family conflict variables and the perception of gender equity, as well as in the work-family conflict and subjective well-being variables. On the other hand, it is evidenced that there is a statistically significant and positive relationship between the perception of gender equity and subjective well-being. It is concluded that it is necessary to face the social changes that have been experienced with the insertion of women into the labor market and how a mismatch occurs in terms of work- family conciliation, understanding the post-pandemic challenges.

Keywords: work- family conflict; perception of gender equity; subjective well-being; public companies

El objetivo del presente trabajo fue describir la relación que existe entre conflicto trabajo- familia, percepción de equidad de género y bienestar subjetivo en funcionarios de la salud en la región del Maule (Chile). A 255 funcionarios de tres servicios públicos de salud se les administraron los instrumentos de Escala CTF/CFT, Cuestionario de Percepción de Equidad de Género, Escala de Satisfacción Vital y la Escala de Felicidad Subjetiva. Se observó que la dirección del conflicto trabajo-familia se orienta predominantemente de la familia hacia el trabajo. Asimismo, se encontró que existe una relación estadísticamente significativa y negativa entre las variables de conflicto trabajo-familia y la percepción de equidad de género, al igual que en las variables de conflicto trabajo-familia y bienestar subjetivo. Por el contrario, se evidencia que existe una relación estadísticamente significativa y positiva entre la percepción de equidad de género y el bienestar subjetivo. Se concluye la necesidad de afrontar los cambios sociales que se han ido experimentando con la inserción de la mujer al mundo laboral y en cómo ocurre un desajuste en términos de conciliación trabajo-familia a partir de los desafíos pospandemia.

Palabras clave: conflicto trabajo-familia; percepción de equidad de género; bienestar subjetivo; empresas públicas

O objetivo deste trabalho foi descrever a relação que existe entre conflito trabalho- família, percepção de equidade de gênero e bem-estar subjetivo em funcionários da saúde na região de Maule. A 255 funcionários de três serviços públicos de saúde, foram administrados os instrumentos Escala CTF/CTF, Questionário de Percepção de Equidade de Gênero, Escala de Satisfação Vital e Escala de Felicidade Subjetiva. Observou-se que a direção do conflito trabalho-família se orienta predominantemente da família para o trabalho. Também se verificou que existe uma relação estatisticamente significativa e negativa entre as variáveis de conflito trabalho-família e a percepção de equidade de gênero, da mesma forma que as variáveis de conflito trabalho-família e bem-estar subjetivo. Contrariamente, é evidente que existe uma relação estatisticamente significativa e positiva entre a percepção de equidade de gênero e o bem-estar subjetivo. Conclui-se a necessidade de enfrentar as mudanças sociais que vão sendo experimentadas com a inserção da mulher no mundo do trabalho e em como ocorre um desajuste em termos da conciliação trabalho-família, compreendendo os desafios pós-pandemia.

Palavras-chave: conflito trabalho-família; percepção de equidade de gênero; bem-estar subjetivo; empresas públicas

The recent COVID-19 health crisis has affected every sphere of the population, but especially the front line of medical health, where workers have had to face long working hours and work overloads that have consequences on physical and mental health.

Salgado and Leria, (2019) state that primary care health officials are subjected to highly demanding performance conditions, particularly due to the excessive workload and number of users attended daily, which leads to symptoms of fatigue due to the long working hours to which they are exposed. Likewise, Ybaseta-Medina and Becerra-Canales (2020) state that health personnel are exposed to constant work stressors such as scarcity of protective equipment, permanent need for concentration and vigilance, as well as strict security measures.

The percentage of women within the health personnel at different levels is in the majority and despite this, the perpetuation of gender roles and stereotypes continues in the home, where it is the woman who assumes the double presence, taking charge of both work and household chores (Fonseca, 2020; Muñoz et al., 2020).

The participation of women in the market has brought with it problems of discrimination in terms of access, working conditions, remuneration and permanence in jobs, which leads to a situation of inequity and gender inequality (Meza, 2018). The concept of gender equity in the labor area appears associated with the massive incorporation of women into the market. The strong female insertion into the labor market not only posed problems in family dynamics, but also within their jobs, where there are large gender differences (Jiménez & Hernández, 2020).

According to Cuenca et al. (2017) the gender perspective refers to the approach that allows evaluating how policies, programs, projects and activities impact both men and women and also takes into account gender-based roles, relationships, resources, social/economic needs and other constraints imposed by society, culture or ethnicity. In this context, it is important to analyze the impact on quality of life, in particular on well-being, since family and work are considered to occupy an important place in explaining the overall satisfaction and global well-being of the working person (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000).

In the mid-1980s, the idea of work-family conflict was defined as a role conflict in which the pressures arising from paid work and the pressures of family life are incompatible (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Subsequently, a bidirectional perspective was added to this theory: work can interfere with family and family can interfere with work (Frone, 2000).

On the other hand, according to Gómez and Jiménez (2019) the sexual division of labor, which referred to men as providers and women as caregivers, implied a specialization in terms of gender lines that relegated reproductive work in the context of the family, domestic and care tasks to the private space, leaving it in the background as socially valuable work and configuring a type of inequality rooted in the social organization itself. Currently, this has been changing due to the massive incorporation of women into the world of work, which has had a direct impact on family-work spaces in both women and men who integrate, participate, form and interact in the world of work and family (Beltrones et al., 2015; Kreis et al., 2022).

The role of organizations in the exercise of equitable redistribution of roles in the home implies the creation of policies that allow the facilitation of work and family life for both men and women (Balmforth & Garden, 2006), since adopting organizational practices that are not equitable between genders can provoke feelings of injustice, which affect performance within the company, causing a disengagement from their work (Lambert et al., 2001). Public policies and labor legislation are a privileged tool to initiate changes in the way families can distribute tasks within the household, which can lead to greater gender equity within and outside the sphere of paid work (Jiménez & Gómez, 2014).

According to Hernández and Ibarra (2020), in order for there to be equal opportunities for male and female workers, there must be favorable organizational practices such as flexible working hours, such as part-time or teleworking; however, these practices are only adopted mainly by women and only manage to make their time more flexible, but they do not achieve a work-life balance.

For Flores (2015), the wage gap between men and women in Chile is an issue to be addressed. In order to reduce it, Law No. 20.34898 was passed in 2009 to safeguard the right to equal remuneration. Also, the legislation on male postnatal leave was approved, represented by Law 20.047100, which presents a paid leave of 4 days for the father in case of the birth of a son or daughter. It should be noted that for women who are inserted in the labor market, the rights to food, nursery and childcare are inalienable (Silva, 2018).

A relevant aspect of empowering and promoting women's participation in the world on equal terms with men is to move towards a culture of co-responsibility (Kreis et al., 2022). Following this line of research, the importance of describing the issue of family co- responsibility arises, since it aims to achieve greater equality and equity between men and women, as well as to generate greater equality of opportunities and increase work-family reconciliation (Jiménez & Gómez, 2015).

According to the Foundation for the Promotion and Development of Women (PRODEMU, 2021), co-responsibility explains the organization and distribution of household chores and family responsibilities among the members of a household. It is mentioned that this distribution is a consequence of an agreement within the family group and in addition to this, public policies and organizations can expand or reduce the margins of agreement available to men and women, in terms of facilitating or hindering the distribution of family responsibilities in a more equitable way (Gómez & Jiménez, 2019).

Making way for the legislative issue in Chile regarding family co-responsibility, as of 2011, the legislation (Law 20.545) added to the established norm of maternal rest a twelve- week parental postnatal leave, i.e., it is the right to rest that the mother has immediately after her postnatal rest with the possibility of transferring part of the rest time to the father, at the mother's choice from the seventh week (Jiménez & Gómez, 2015).

A barrier that hinders reconciliation and co-responsibility in the home is that historically men have not been significantly involved in household chores, this may often be due to the organization and schedules at work, the cultural context and activities rooted in gender stereotypes (Hernández & Ibarra, 2020). Likewise, Jiménez and Hernández (2020) mention that Chilean society makes a distinction between the different roles of men and women, producing gender inequalities, in which women fulfill the role of performing tasks such as mother, wife and housewife.

On the other hand, it has been found that there is a strong association between a responsible family culture and company performance. However, it is not enough just to have policies, but also to have an organizational culture that supports the reconciliation of work and family, and for this the real support provided by middle management and supervisors in a company is key, since they are the ones who decide on the application of practices in daily work life (Chinchilla et al., 2003).

The effects of public policies include improving the quality of leadership and economic results of the company, increasing diversity and improving problem solving, increasing the level of organization and effectiveness, reducing the wage gap, attracting female talent and obtaining benefits through greater parental involvement of employees (Kreis et al., 2022). Following this line, Lambert (1990) affirms that the inclusion of organizational policies that promote family-work integration significantly reduces absenteeism levels and improves work performance, which favors organizations.

In accordance with the above, the National Institute of Statistics (2021) reported in the last national time use survey, it was found that the hours dedicated to unpaid work in a typical day, for men equaled 2.74 and for women 5.89. Dual presence is one of those responsible for the maintenance of labor inequality between men and women, as domestic obligations prevent women from dedicating themselves more intensely to their jobs (Moreno & Garrosa, 2013; Sorbara et al., 2021). However, the globalized world in a certain sense forces women to work in paid jobs in search of better living conditions, without leaving aside their family and domestic activities. This represents what has been called double workday or double presence, causing a high degree of fatigue in those who perform it (Ramírez & Cota, 2017).

According to Alcañiz (2015), the reconciliation of the spheres of work and family aims that women do not perform both roles, but that both roles can be distributed by both genders, this implies an empowerment of public and private environments by people, rather than by gender. Papí (2005) states that the conflict produced by trying to reconcile work and family would benefit women belonging to companies or organizations, since the implementation of practices to reduce the double working day, to work part-time and to assume shared responsibilities, favor the principle of gender equality and work-family balance.

Authors such as Jiménez et al. (2019), state that if work gets in the way of family life, it will have an impact on the subjective well-being of the person. Results obtained in a study by Paris (2011) show that the variables that are predictors of well-being at work are: the perception of support from the organization and the family, the consistency between achievements and expectations and also the possibility of promotion at work.

According to Garrosa and Carmona (2011) and Ramos et al. (2020) a positive organizational culture that fosters social support, recognition of its workers and a positive work environment will contribute to worker well-being and, therefore, to the reduction of pathologies.

It is posited that when family commitments are perceived as competing with work opportunities, this increases work-family conflict and also the inequitable distribution of life opportunities between men and women, which impacts the subjective well-being of workers (Jiménez & Gómez, 2014).

On the other hand, there is a relationship between the variables of work-family balance and subjective well-being, so that if a person notices that he/she has enough time to satisfy both personal and professional needs, his/her work-family conflict decreases, and his/her well-being levels will increase (Gröpel & Kuhl, 2009; Saltos, 2022).

According to Frone et al. (1992) there is a mutual relationship between work-family and family-work conflict, centered on the assumption that, for example, if there is an overload or high demand at work, this begins to hinder and interfere with the duties corresponding to the family, and these obligations, when not satisfied, may begin to interfere with work obligations. According to Sanz (2011), there are several moderating variables in the work-family conflict process. At the individual level, he points out that coping strategies are relevant when a conflict is generated, as well as personality characteristics, indicating that when faced with the same stressors, not all individuals experience the same levels of conflict. Evidence has been found that perceived organizational support and work-related quality of life are associated with workers' subjective well-being (Salazar, 2018). Following this line, the support exerted by the organization in pursuit of workers' well-being has an impact on subjective well-being.

The purpose of this study was based on the study of work-family conflict, perception of gender equity and subjective wellbeing in health officials of the Maule region. Knowing these variables is relevant when entering the world of work in public health institutions, since knowing the public policies that have been adopted on issues of gender equity perspective, work-family conciliation and family co-responsibility has an impact on the quality of work and family experienced by workers. The recognition of these variables in the organizational environment will allow the management of models and strategies that support workers.

The research question guiding this study is: How are the variables of work-family reconciliation, perception of gender equity and subjective well-being related? The specific objectives are:

-To determine the levels of work-family conflict in health care workers.

-To analyze the relationship between work-family conflict and perception of gender equity among health officials.

-To analyze the relationship between work-family conflict and subjective well-being in health care workers.

-To analyze the relationship between the perception of gender equity and subjective well-being among health officials.

Based on the background review, the following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1: The conflict experienced by health officials goes in the direction of work to family.

H2: There is a statistically significant and negative relationship between the work-family conflict variable and the gender equity perception variable.

H3: There is a statistically significant and negative relationship between the work- family conflict variable and the subjective well-being variable.

H4: There is a statistically significant and positive relationship between the gender equity perception variable and subjective well-being.

Method

Participants

The participants are men and women who work in public health services, for a total of 255 employees (202 women, 52 men and 1 participant who does not identify with either gender).

Instruments

CTF/CFT Scale. An instrument developed by Carlson et al. in 2000 and consisting of 18 items with a Likert-type scale, in which the statements range from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). It measures the direction of the conflict and reports the type of conflict in three dimensions: stress-based conflict, behavior-based conflict and time-based conflict. The scale measures the presence or absence of conflict between work and family roles, in which the requirements associated with each role interfere or are incompatible with the other role (Quezada et al., 2010). It has a Cronbach's alpha reliability of .87 (Jiménez et al., 2012).

Gender Equity Perception Questionnaire. Developed by Gómez and Jiménez (2015). The questionnaire consists of 21 statements, which are answered using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree), and are distributed in 4 subscales: Perception of availability of personal time (3 items), Perception of distribution of responsibilities for domestic care work (5 items), Perception of distribution of responsibilities for economic support of the household (3 items), and Perception of distribution of labor demands (3 items). The validation of the instrument yielded a Cronbach's alpha index of .87, this being an indicator of high reliability (Gómez & Jiménez, 2015).

Life Satisfaction Scale. Developed by Diener et al. in 1984, it is composed of 5 items that assess life satisfaction through the overall judgment that people make about life (Padrós et al., 2015). They are answered by means of a Likert-type scale, which ranges from 1 (I strongly disagree) to 7 (I strongly agree). The life satisfaction scale (ESV) has an internal consistency measured by Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .87 (Moyano & Ramos, 2007).

Subjective Happiness Scale. Instrument developed by Lyubomirsky and Lepper, in 1999. The subjective happiness scale is a global measure, which rates a molar class of well- being as a psychological phenomenon viewed in a global way. The definition of happiness used is from the perspective of the individual responding to the questionnaire, having 4 items and being Likert-type from 1 (Less happy) to 7 (Happier). It has a Cronbach's alpha internal consistency of .79 (Moyano & Ramos, 2007).

Procedure

The study proposal was endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the Maule Health Service. It was then presented to different institutions in the Maule region, who authorized the administration of questionnaires. Dates were agreed upon for raising awareness and subsequent application of instruments through the "Google forms" platform. The sensitization process was carried out through a video capsule and a poster for each of the institutions and then the instruments began to be applied in January 2021 until mid-July 2021.

Data design and analysis

Cross-sectional descriptive correlational study. To carry out the analyses, tables of descriptive statistics were obtained for the work-family conflict scale, gender equity perception questionnaire, life satisfaction scale and subjective happiness scale. Subsequently, a Student's t-test for related samples was performed to test the first specific objective related to determining the direction of the work-family conflict scale, since it has two theoretical directions (work-family conflict and family-work conflict) and the aim was to observe the difference between the means of both spheres and to see the direction of the conflict in this variable. To carry out the second, third and fourth specific objectives, Pearson's correlation coefficient and Spearman's correlation coefficient tests were carried out because a normality test was performed to verify the distribution of the variables, finding that the scales of perception of gender equity (PEG) and work-family conflict (ECTF) were normally distributed, Therefore, a parametric test was used (Pearson's correlation coefficient) and for the life satisfaction (ESV) and subjective happiness (EFS) scales it was found that they did not have a normal distribution, so a non-parametric test was used (Spearman's correlation coefficient). The results were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS version 25 software.

Results

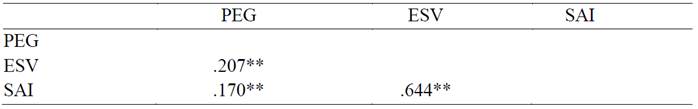

Table 1 shows the results of the normality test. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic was used in this test because it is the most suitable for sample sizes of more than 50 cases. Only the PEG and ECTF variables were found to be normally distributed (p< .05).

Table 1: Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test

Note: PEG: gender equity perception; ESV: life satisfaction scale; EFS: subjective happiness scale; ECTF: work-family conflict scale.

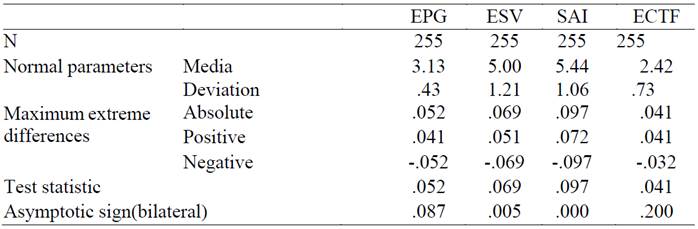

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables age, number of children, hours spent at home, years of experience in the institution and the scales of work-family conflict (ECTF), perception of gender equity (PEG), life satisfaction (ESV) and subjective happiness (EFS). The EFS scale shows a higher mean (M = 5.44) compared to the midpoint of the same scale (M = 3.5), as does the ESV scale (M = 5.00) and the PEG scale (M = 3.13). In contrast, the ECTF scale (M = 2.42) is below the midpoint of the same scale (M = 2.5).

On the other hand, regarding the frequency of the variables gender, level of studies, marital status, whether or not they are in charge of older adults and type of contract respectively, it is highlighted that 79.2 % of the respondents are women, 71.8 % have a technical or higher university education and 40.4% are single, 33.7 % are married and 19.2 % are cohabitants.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics (N = 255)

Note: PEG: gender equity perception; ESV: life satisfaction scale; EFS: subjective happiness scale; ECTF: work-family conflict scale.

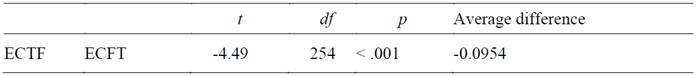

With respect to the Student's t-test, Table 3 found that there is a significant difference (t= -4.49; p< .001) between both directions of the work-family and family-work conflict, this difference being -0.0954. In addition, it is observed that the direction of the conflict is family-work, due to the fact that this has a higher average (M = 2.48) than the work-family conflict (M = 2.38).

Table 3: t-test for related samples (N = 255)

Note: ECTF: work-family conflict scale; ECFT: work-family scale.

With respect to the correlation between work-family conflict and perception of gender equity, a significant, negative and moderate correlation was found between the variables ECTF and PEG (r= -.408; p< .001). This means that as the ECTF variable increases, PEG decreases and vice versa.

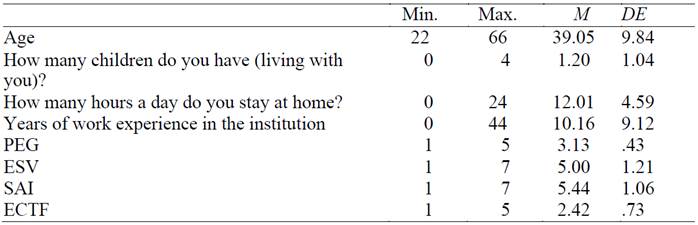

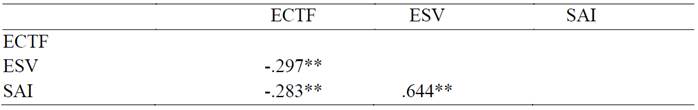

Table 4 shows that there is a significant, negative and low correlation between ECTF and ESV and between ECTF and EFS. In addition, a significant, positive and strong correlation is observed between the variables ESV and EFS.

Table 4: Correlation scales work-family conflict, life satisfaction, subjective happiness (N = 255)

Note: ECTF: work-family conflict scale; ESV: life satisfaction scale; EFS: subjective happiness scale. **p < .001.

Finally, Table 5 shows that there is a significant, positive and weak correlation between the PEG and ESV variables and between the PEG and EFS variables.

Discussion and Conclusion

The general objective developed for this study was to describe the relationship between work-family reconciliation, the perception of gender equity and the subjective wellbeing of health officials in the Maule region, for which 4 hypotheses were formulated concerning 4 specific objectives that are presented below through the discussion of the results obtained.

For the first hypothesis proposed, it was found that the direction of the conflict is oriented from family to work and not from work to family as initially proposed. Therefore, the hypothesis of the first specific objective is rejected. This result may be due to several factors. In the first place, the direction of the conflict found may be due to the fact that the sample is mostly female, since the population of women in the sample corresponds to 79%. This is due to the fact that the percentage of women within the health personnel at different levels is in the majority and despite this, the perpetuation of gender roles and stereotypes continues in the home, where it is the woman who bears the double presence (Fonseca, 2020; Muñoz et al., 2020).

On the other hand, Jiménez and Hernández (2020) also point out that Chilean society makes a distinction between the different roles of men and women, producing gender inequalities, in which women fulfill the role of performing tasks such as mother, wife and housewife. The aforementioned could be the cause of women feeling pressured to perform more of the family's tasks and therefore produce an imbalance between work and family. Another related cause is the one presented by Hernandez and Ibarra (2020) who state that the organizational practices that mostly exist to reconcile work and family only manage to make their time more flexible, but do not achieve a reconciliation.

It should be noted that the difference between the two spheres of conflict is low, and this could be due to the fact that there are currently policies that promote gender equity within organizations, and this promotes work-family reconciliation and therefore a reduction in conflict. On the other hand, it is pointed out that public policies and labor legislation are a privileged tool to initiate changes in the ways in which families can distribute tasks within the home, which can lead to greater gender equity within and outside the sphere of paid work. It is for this reason that the policies implemented in institutions function as a regulator of work-family conflict (Jiménez & Gómez, 2014).

For the second hypothesis, it was found that there is a statistically significant, negative and moderately low correlation between increased work-family conflict and the perception of gender equity. Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted. That is, as work-family conflict increases, the perception of gender equity decreases or vice versa. The above may have different reasons, one of them is that the current world in a certain sense forces women to perform in paid jobs, without leaving aside family and domestic activities, which causes a high degree of fatigue and the search for balancing both spheres (Ramírez & Cota, 2017). On the other hand, the authors Moreno and Garrosa (2013) and Sorbara et al. (2021) state that dual presence is one of those responsible for the maintenance of labor inequality between men and women, since domestic obligations prevent women from dedicating themselves more intensely to their jobs. In the case of the present research, the sample is 79% female, and since there is evidence of the double presence that women experience even today, it can be concluded that their perception of equity could be affected. Papí (2005) states that the conflict produced by trying to reconcile work and family would benefit women belonging to organizations, in this way the implementation of practices such as reducing the double working day, working part-time and assuming shared responsibilities benefit and enhance the principle of gender equality and work-family balance.

For the third hypothesis, it was found that there is a statistically significant, negative and low correlation between the work-family conflict variable and subjective well-being. Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted. That is, as work-family conflict increases, subjective well-being decreases or vice versa. This can be explained under the approach of authors such as Jiménez et al. (2019), who state that, if work gets in the way of family life, this will have repercussions on the person's subjective well-being. On the contrary, it is commented that when there is a work-family balance, subjective well-being is influenced in a positive way. In agreement with Gröpel and Kuhl (2009) and Saltos (2022) it is mentioned that there is a relationship between the variables of work-family balance and subjective well-being, so that if a person notices that he/she has enough time to satisfy both personal and work needs, his/her work-family conflict will decrease and his/her levels of well-being will increase. On the other hand, Jiménez and Gómez (2014) propose that when family responsibilities are seen as competing with work opportunities, this fosters work-family conflict, as well as the inequitable distribution of life opportunities between men and women, and therefore has an impact on the subjective well-being of workers.

For the fourth hypothesis, it was found that there is a statistically significant, positive and low correlation between the perception of gender equity and subjective well-being. Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted. That is, as the perception of gender equity increases, subjective well-being increases.

The search for greater gender equality has focused its importance on housework as a primary element for people's well-being, as this influences the reconciliation between work and family and the tensions that this can cause in both spheres (Gómez & Jiménez, 2019).

Subsequently, from a gender equity scenario, in the world of work, evidence was found that perceived organizational support and work-related quality of life are associated with the subjective well-being of workers (Salazar, 2018). Therefore, the support of the organization in legislative matters in order to promote gender equity is of great relevance.

In conclusion, it can be said that the role of women in society has been changing over the years, as has the role of men. Women are no longer seen exclusively as the ones in charge of domestic chores, care and upbringing, but have been incorporated into the labor market, reflecting their ability to perform paid work and breaking with the stereotypes associated with gender. However, it is precisely with this female insertion into the labor market that a mismatch begins to occur in terms of work-family reconciliation. This is substantially due to the double presence or double role that women perform and that has been socially assigned to them. This is because public policies and also organizational practices help to regulate the work-family conflict and the perception of gender equity, making both variables influence people's subjective wellbeing and quality of life. Public policies turn out to be useful to begin to generate changes in the distribution of tasks in the home, thus generating greater gender equity, an equity that is currently of great importance for the new generations, given that it is increasingly present in public discourse (Jiménez & Gómez, 2014).

On the other hand, it is known that companies or organizations implement public policies regarding gender equity, however, it is considered that it is not enough only with a regulation by the organizations, but it is also a work by the state, who must take care of the interests of the families of the country, developing regulatory and legal frameworks on labor policies that benefit the balance between the spheres of work and family in a scenario of gender equity (Jiménez & Gómez, 2014). This helps to generate work environments where a work-family conciliation culture is promoted within organizations.

There is no denying the advances in public policies that have been established in the sphere of work and family, improvements that have helped to balance the scales in terms of gender equity and that try to reconcile the work-family conflict of workers. Some of these policies are Law No. 20.34898 to safeguard the right to equal pay. In the same way, Law No. 20.047100 is approved, which presents a paid leave of 4 days for the father in case of the birth of a son or daughter (Flores, 2015). Also in Chile, for working women, the right to a cradle room, food and care of a minor child are inalienable rights (Silva, 2018).

As for the limitations of the study, it was found that the sample found had a high percentage of female participation, so it was not possible to carry out analyses that would make it possible to show differences by sex. On the other hand, the sample used corresponds to workers from public entities, so it was not possible to make comparisons of the variables used with workers from private companies in terms of organizational policies oriented to gender equity. Finally, an important limitation of this research is that the data collection was carried out remotely, which could have limited the sample size.

Considering the above, possible lines of research to work on are the differences by sex between men and women with respect to the variables. On the other hand, in relation to the sample, it is considered relevant to incorporate workers from private companies, in order to compare the differences between public and private organizations in relation to work- family conciliation, the perception of gender equity and subjective wellbeing and how the link to public policies influences their organizational practices. Another important aspect would be to be able to study the variables mentioned in a sample that has experienced the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and a post-pandemic sample, that is, to study these same variables in a similar sample, but without the effects of the pandemic and compare their results. Finally, it is suggested to incorporate a mixed methodology, including qualitative and quantitative instruments in order to have a wider scope of the variables, being able to know the perception and attitudes of the workers.

REFERENCES

Alcañiz, M. (2015). Género con clase: La conciliación desigual de la vida laboral y familiar. Revista Española de Sociología, 23, 29-55. [ Links ]

Balmforth, K. & Garden, D. (2006). Conflict and facilitation between work and family: realizing the outcomes for organizations. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 35(2), 69-76. [ Links ]

Beltrones, G., Miranda, V., Ontiveros, R., & Nuñez, R. (2015). Incorporación masiva de la mujer al mundo laboral, factor determinante en las políticas de armonización trabajo-familia. Biolex Revista Jurídica Del Departamento De Derecho, 12, 37-50. https://doi.org/10.36796/biolex.v12i0.78 [ Links ]

Chinchilla, M., Poelmans, S., & León, C. (2003). Políticas de conciliación trabajo-familia en 150 empresas españolas. IESE Business School, 498, 1-45. [ Links ]

Cuenca, L., Navarro, E., Alemany, M., & Boza, A. (2017). Áreas clave para la alineación de la agilidad y resiliencia con la perspectiva de género en las organizaciones. Dirección y Organización, 57-64. https://doi.org/10.37610/dyo.v0i0.515 [ Links ]

Edwards, J. & Rothbard, N. (2000). Mechanism linking work and family: clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management. 25, 178-1999. [ Links ]

Flores, A. (2015). Políticas públicas de igualdad de género en Chile y Costa Rica. Un estudio comparado (Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid). https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/38021/1/T37316.pdf [ Links ]

Fonseca, I. (2020). Influencia del género en la salud de las mujeres cuidadoras familiares. Revista Chilena de Terapia Ocupacional, 20(2), 211-219. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-5346.2020.51517 [ Links ]

Frone, M. (2000). Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: The national comorbidity survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 888-895. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.888 [ Links ]

Frone, M., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65-78. [ Links ]

Garrosa, E. & Carmona, I. (2011). Salud laboral y bienestar: Incorporación de modelos positivos a la comprensión y prevención de los riesgos psicosociales del trabajo. Medicina y Seguridad del Trabajo, 57(1), 224-238. https://doi.org/10.4321/s0465-546x2011000500014 [ Links ]

Gómez, V. & Jiménez, A. (2015). Corresponsabilidad familiar y el equilibrio trabajo-familia: Medios para mejorar la equidad de género. Polis, 14(40), 377-396. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-65682015000100018 [ Links ]

Gómez, V. & Jiménez, A. (2019). Género y trabajo: hacia una agenda nacional de equilibrio trabajo-familia en Chile. Convergencia, 26(79). https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v0i79.10911 [ Links ]

Greenhaus, J. & Beutell, N. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76, 1985. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352 [ Links ]

Gröpel, P. & Kuhl, J. (2009). Work-life balance and subjective well‐being: The mediating role of need fulfilment. British Journal of Psychology, 100(2), 365-375. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712608X337797 [ Links ]

Hernández, M. & Ibarra, L. (2020). Dos ingresos, dos cuidadores. Barreras a la conciliación trabajo-familia. Latinoamericana de Estudios de Familia, 12(2), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.17151/rlef.2020.12.2.2 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. (2021). Encuesta Nacional de uso del tiempo 2015. https://www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/sociales/genero/uso-del-tiempo [ Links ]

Jiménez, A. & Gómez, V. (2014). Corresponsabilidad familiar, prácticas organizacionales, equilibrio trabajo-familia y bienestar subjetivo en Chile. Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 14(27), 85-96. https://doi.org/10.22518/16578953.181 [ Links ]

Jiménez, A. & Gómez, V. (2015). Conciliando trabajo-familia: análisis desde la perspectiva de género. Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología, 11(2), 289-302. [ Links ]

Jiménez, A. & Hernández, A. (2020). Percepción de equidad de género y equilibrio trabajo-familia en trabajadores pertenecientes a empresas públicas y privadas de Chile. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2201 [ Links ]

Jiménez, A., Concha, M., & Zúñiga, R. (2012). Conflicto trabajo-familia, autoeficacia parental y estilos parentales percibidos en padres y madres de la ciudad de Talca, Chile. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 15(1), 57-65. [ Links ]

Jiménez, A., Sepúlveda, F., & Faúndez, M. (2019). Conflicto trabajo-familia, equilibrio y bienestar en mujeres trabajadoras de una empresa de retail, dependiendo de su rol de proveedor. Géneros, 26(25), 77-98. [ Links ]

Kreis, M., Riumalló, M., & Morgado, M. (2022). Corresponsabilidad: clave para un desarrollo sostenible. Ese Business School. https://www.ese.cl/ese/site/artic/20220413/asocfile/20220413104431/estudio_corresponsabilidad_versi__n_final_digital.pdf [ Links ]

Lambert, E., Hogan, N., & Barton, S. (2001). The impact of job satisfaction on turnover intent: a test of a structural measurement model using a national sample of workers. The Social Science Journal, 38, 233-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0362-3319(01)00110-0 [ Links ]

Lambert, S. (1990). Processes linking work and family: a critical review and research agenda. Human Relations, 43, 239-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679004300303 [ Links ]

Meza, A. (2018). Discriminación laboral por género: una mirada desde el efecto techo de cristal. Equidad y Desarrollo, 1(32), 11-31. https://doi.org/10.19052/ed.5243 [ Links ]

Moreno, B. & Garrosa, E. (2013). Salud laboral. Pirámide. [ Links ]

Moyano, E. & Ramos, N. (2007). Bienestar subjetivo: midiendo satisfacción vital, felicidad y salud en población chilena de la Región Maule. Universum (Talca), 22(2), 177-193. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-23762007000200012 [ Links ]

Muñoz, S., Molina, D., Ochoa, R., Sánchez, O., & Esquivel, J. (2020). Estrés, respuestas emocionales, factores de riesgo, psicopatología y manejo del personal de salud durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Acta Pediátrica de México, 41(1), 127-136. https://doi.org/10.18233/apm41no4s1pps127-s1362104 [ Links ]

Padrós, F., Gutiérrez, C. & Medina, M. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida (SWLS) de Diener en población de Michoacán (México). Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 33(2), 221-230. https://doi.org/10.12804/apl33.02.2015.04 [ Links ]

Papí, N. (2005). La conciliación de la vida laboral y familiar como proyecto de calidad de vida desde la igualdad. Revista Española de Sociología, 5, 91-107. [ Links ]

Paris, L. (2011). Predictores de satisfacción laboral y bienestar subjetivo en profesionales de la salud: un estudio con médicos y enfermeros de la ciudad de Rosario. Psicodebate. Psicología, cultura y sociedad, (11), 89-102. https://doi.org/10.18682/pd.v11i0.378 [ Links ]

Promoción y Desarrollo de la Mujer. (2021). Corresponsabilidad familiar: ¿un favor o una responsabilidad?https://www.prodemu.cl/2021/03/31/corresponsabilidad-familiar-un-favor-o-una-responsabilidad/ [ Links ]

Quezada, F., Sanhueza, A., & Silva, F. (2010). Diagnóstico de la calidad de vida laboral percibida por los trabajadores de cuatro servicios clínicos del complejo asistencial Dr. Víctor Ríos Ruiz de Los Ángeles. Horizontes Empresariales, 9(1), 55-68. [ Links ]

Ramírez, L. & Cota, B. (2017). La doble presencia de las mujeres: conexiones entre trabajo no remunerado, construcción de afectos-cuidados y trabajo remunerado. Margen: Revista de trabajo social y ciencias sociales, 85. [ Links ]

Ramos, A., Coral, J., Villota, K., Cabrera, C., Herrera, J., E Ivera, D. (2020). Salud laboral en administrativos de Educación Superior: Relación entre bienestar psicológico y satisfacción laboral. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacología y Terapéutica, 39(2), 237-250. [ Links ]

Salazar, J. (2018). La relación entre el apoyo organizacional percibido y la calidad de vida relacionada con el trabajo, con la implementación de un modelo de bienestar en la organización. Signos-Investigación en sistemas de gestión, 10(2), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.15332/s2145-1389.2018.0002.02 [ Links ]

Salgado, J. & Leria, F. (2019). Burnout, satisfacción y calidad de vida laboral en funcionarios de la salud pública chilenos. Universidad y Salud, 22(1), 06-16. https://doi.org/10.22267/rus.202201.169 [ Links ]

Saltos, I. (2022). Autoeficacia profesional como moderadora de condiciones de trabajo y calidad de vida laboral en equipo de salud (Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Concepción). Archivo digital. http://repositorio.udec.cl/bitstream/11594/10104/1/Tesis%20Irma%20Saltos.pdf [ Links ]

Sanz, A. (2011). Conciliación y salud laboral: ¿una relación posible? Actualidad en el estudio del conflicto trabajo-familia y la recuperación del estrés. Medicina y Seguridad en el Trabajo, 57, 115-126. https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0465-546X2011000500008 [ Links ]

Silva, C. (2018). Elección de sala cuna: ¿Cuáles son los requerimientos de los padres? Revista Infancia, Educación y Aprendizaje, 4(2), 22-36. https://doi.org/10.22370/ieya.2018.4.2.1179 [ Links ]

Sorbara, S., Baró, S., del Carmen, R., Preiti, M., & Quinteros, M. (2021). Doble presencia, entre la familia y el trabajo. Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, 6(251). https://doi.org/10.32351/rca.v6.251 [ Links ]

Ybaseta-Medina, J. & Becerra-Canales, B. (2020). El personal de salud en la pandemia por COVID-19. Revista Médica Panacea, 9(2), 72-73. https://doi.org/10.35563/rmp.v9i2.322 [ Links ]

How to cite: Jiménez-Figueroa, A., Busto-Ramírez, A., & Orellana-Cornejo, M. (2023). Work-family conflict, perception of gender equality and subjective well-being of health officials in the Maule Region. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2904. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2904

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. A. J.F. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; A. B.R. in a, b, c, d, e; M. O.C. in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: May 12, 2022; Accepted: February 15, 2023

text in

text in