Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.16 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2794

Original Articles

Stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being and life satisfaction according to work modalities in mothers of families

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ambato, Ecuador, isavallepico@gmail.com

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ambato, Ecuador

The purpose of the research was to compare stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction according to work patterns in mothers. A descriptive and comparative study was carried out, with a non-experimental design, quantitative and cross-sectional approach. The participants were 436 Ecuadorian mothers, divided into three groups: face-to-face work, telework, and unpaid work. The ANOVA statistical analysis indicated significant differences in the variables of psychological distress (F = 4.67; p < .01), psychological well-being (F = 7.64; p < .001), and life satisfaction (F = 8.69; p < .001), with unpaid work group showing higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of well-being and satisfaction, and teleworking with better scores in well-being and satisfaction and low levels of psychological distress. Differences in stress were found between the groups (F= 5.13; p = .02) when the covariate educational follow-up through ANCOVA is analyzed. The unpaid work group presented higher levels of stress as the hours of educational follow-up increased. It is concluded that work mode is related to psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction. Stress levels increase as a function of modality and when more hours of educational follow-up are allocated.

Keywords: stress; psychological distress; psychological well-being; life satisfaction; work modality

La investigación tuvo como propósito comparar estrés, malestar psicológico, bienestar psicológico y satisfacción con la vida según las modalidades de trabajo en madres de familia. Se realizó un estudio descriptivo y comparativo, con diseño no experimental, enfoque cuantitativo y de corte transversal. Las participantes fueron 436 madres ecuatorianas, divididas en tres grupos: trabajo presencial, teletrabajo y trabajo no remunerado. El análisis estadístico ANOVA indicó diferencias significativas en las variables de malestar psicológico (F = 4.67; p < .01), bienestar psicológico (F = 7.64; p < .001) y satisfacción con la vida (F= 8.69; p < .001), siendo el grupo de trabajo no remunerado el que muestra mayores niveles de malestar psicológico y menores niveles en bienestar y satisfacción, y el teletrabajo con mejores puntuaciones en bienestar y satisfacción y bajos niveles en malestar psicológico. Se encontró en el estrés diferencias entre los grupos (F = 5.13; p = .02) al analizarlo con la covariable seguimiento educativo a través del ANCOVA. El grupo de trabajo no remunerado presentó niveles más altos en estrés al aumentar las horas de seguimiento educativo. Se concluye que la modalidad de trabajo está relacionada con el malestar psicológico, bienestar psicológico y satisfacción con la vida. Los niveles de estrés varían en función de la modalidad y aumentan cuando se destina más horas de seguimiento educativo.

Palabras clave: estrés; malestar psicológico; bienestar psicológico; satisfacción con la vida; modalidades de trabajo

O objetivo desta pesquisa foi comparar o estresse, o mal-estar psicológico, o bem-estar psicológico e a satisfação com a vida segundo as modalidades de trabalho das mães de família. Foi realizado um estudo descritivo e comparativo, com um desenho não-experimental, enfoque quantitativo e corte transversal. As participantes foram 436 mães equatorianas, divididas em três grupos: trabalho presencial, teletrabalho e trabalho não remunerado. A análise estatística da ANOVA indicou diferenças significativas nas variáveis de mal-estar psicológico (F= 4,67;p< 0,01), bem-estar psicológico (F= 7,64;p< 0,001) e satisfação com a vida (F= 8.69;p< 0,001), sendo o grupo de trabalho não remunerado o que apresenta níveis mais altos de mal-estar psicológico e níveis mais baixos de bem-estar e satisfação com a vida; e o de teletrabalho com os melhores resultados em bem-estar e satisfação e baixos níveis de mal-estar psicológico. Foram encontradas diferenças de estresse entre os grupos (F= 5,13;p= 0,02) quando analisados com a covariável de acompanhamento educacional através da ANCOVA. O grupo de trabalho não remunerado apresentou níveis mais altos de estresse à medida que as horas de acompanhamento educacional aumentavam. Conclui-se que a modalidade de trabalho está relacionada ao mal-estar psicológico, ao bem-estar psicológico e à satisfação com a vida. Os níveis de estresse variam em função da modalidade e aumentam quando se destinam mais horas de acompanhamento educacional.

Palavras-chave: estresse; mal-estar psicológico; bem-estar psicológico; satisfação com a vida; modalidades de trabalho

As of March 2020, the Coronavirus has affected health globally, the viral pathology caused deaths and high levels of contagion (Vázquez et al., 2020). To curb the spread of the virus, the Ecuadorian government decrees a state of emergency due to public calamity and determined emergency measures: school closures and the total suspension of the school day, implementing distance work, through Executive Decree No. 1017-2020 (Corte Constitucional del Ecuador, 2020). However, there was also a reduction in working hours to avoid massive employee layoffs (Möhring et al., 2020); and in other cases, the loss of income, both for mothers and fathers, as a result of the economic and financial problems experienced by the companies (Llanes & Pacheco, 2021).

In the course of this crisis, some mothers withdrew from the labor market to devote their time and attention to household chores, virtual education support, childcare, elder care, and family members with COVID-19 (Esteves, 2020; Gordon, 2021; Manrique & De Jesús, 2020).

Labor conditions seem to play a crucial role in the psychological adjustment of the family. The results of several research allow us to think that there have been psychological difficulties in the people who modified their work; in unpaid work, there is greater psychological distress and in teleworking, there is a greater mental energy drain due to a load of activities (Cusinato et al., 2020; Martiny et al., 2021; Xue & McMunn, 2021). In Ecuador, 76.8 % of unpaid work hours are performed by women, who dedicate an average of 31 hours per week to these activities (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC, 2020).

Moscardino et al. (2021) mention that the sum of the events in the parents can be a significant predictor of parental stress, but increasing their self-efficacy and healthy family functioning significantly reduces symptomatology. According to transactional theory, perceived stress corresponds to the interaction between the person and the environment, that is to say, it is a two-way process: the environment produces stressors and the individual responds to the stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1986). Therefore, perceived stress is the product of the person's threatening interpretation of a situation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Mothers may be the ones who assume several roles within the family environment, but because of COVID-19 can speak of a triple presence: mother, worker, and learning facilitator through virtual education. In this regard, it is worth noting the studies by Calarco et al. (2020) and Möhring et al. (2020) who find that mothers are experiencing anxiety, stress, and frustration due to increased childcare hours, the closing of daycare centers and schools, virtual education, confinement, and work-family reconciliation. Lyttelton et al. (2020) point out that teleworking mothers report increased anxiety, loneliness, and even depressive symptoms. Moreover, the increase in cases of domestic violence generates symptoms of fear and anxiety (Herrera et al., 2021).

Meanwhile, Mayorga and Llerena (2021) state that since SARS-CoV-2, mothers have added to the role of housewife and caregiver of their children, the role of teacher, advisor, class accompanist, legal representative, and support in the fulfillment of duties. This fact seems to have generated varied feelings, some of them more connected to accompanying their children to school, and others as an additional burden to the double presence. Measures chosen to combat the pandemic increase the risk of maternal depression and significant anxiety in mothers of children aged 0 to 8 years (Cameron et al., 2020). However, some women see increased childcare as a source of energy, well-being, and satisfaction in the face of reduced working hours (Calarco et al., 2020; Möhring et al., 2020).

De Clercq and Brieger (2021) point out that women's economic and occupational autonomy may increase their life satisfaction by balancing the needs of work and aspects of their own lives.

The study of well-being is based on two postures: hedonic and eudaimonic. The first, called subjective well-being, is associated with pleasure-displeasure, absence of conflicts, and positive experiences, composed of a cognitive and emotional factor (Arias & García, 2018; Gaxiola & Palomar, 2016). Life satisfaction refers to the cognitive evaluation of life and depends on the perception of interests, expectations, and cultural environment (Diener et al., 1995; Padros et al., 2015). On the other hand, the eudaimonic position is related to human potential and personal growth, defined as psychological well-being (Mayordomo et al., 2016; Moreta et al., 2017).

The most widely accepted theoretical model of psychological well-being is Carol Ryff's multidimensional model, which refers to the effort for the improvement and achievement of the maximum human potential, composed of six dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, mastery of the environment, personal growth, and purpose in life (Moreta et al., 2017; Ryff & Keyes, 1995).

On the contrary, psychological distress is a set of psychic reactions, emotional, and behavioral manifestations that are characterized by their short course, fast evolution, and good prognosis, among the symptoms that are evidenced, are anxiety, and depression, being a secondary response to stressful events (Espíndola et al., 2006).

Based on the above, the COVID-19 pandemic may generate alterations in the mental health of mothers due to changes in family routines concerning work patterns, virtual education, decreased support from family members for childcare, isolation, and social distancing. It is possible the presence of high levels of stress, coupled with anxious and depressive symptoms, related to psychological discomfort.

The research aims to compare the variables of stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction according to the modalities of face-to-face work, telework, and unpaid work.

Materials and Method

Design

Non-experimental, quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive, and comparative analysis between work modalities (face-to-face work, telework, unpaid work).

Population

A total of 436 Ecuadorian mothers with different work modalities, whose children are in virtual education, participated. A non-probabilistic snowball sampling was used for selection with the following inclusion criteria 1) Acceptance of informed consent, 2) Being a mother of a family, 3) Having children in virtual education, and 4) Children with schooling from Initial I to Third Year of High School.

The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 56 years, with a mean of 38.05 and a standard deviation of 7.59. Married marital status prevails in 61.2%. The average number of sons is 2.29. The children's schooling ranges from Initial I to Third Baccalaureate with a predominance in: Third Baccalaureate (f = 71), Seventh grade (f = 69), Sixth grade (f = 66), Eighth grade (f = 61), (First Baccalaureate (f = 55) and Tenth (f = 55). In terms of work modalities, there is a predominance of 56.4% in face-to-face work, 16.5% in telework, and 27.1% in unpaid work. Most of the tasks related to childcare (77.5%) and household care (81.9%) are assumed by the mothers of the family. The educational follow-up of the children ranges from 1 to 2 hours per day in 36.2%. Also, 73.9% of the participants say they support their children in school activities.

Instruments

Sociodemographic sheet: Information was collected on age, marital status, and work modality (face-to-face, telework, unpaid work). Mothers were asked about their type of work at that time, understanding that face-to-face work is remunerated and carried out in the place established by the institution (Camacho, 2021), and teleworking is remunerated without requiring the physical presence of the employee (Isch, 2020), and unpaid work corresponds to activities inside or outside the home without remuneration in exchange, such as unpaid domestic work (Castillo, 2015). The number of children, schooling of each child, childcare, who performs household activities, hours dedicated to educational follow-up, that is, support in virtual classes and homework, as well as sending and receiving homework, and who supports the educational work was inquired.

Cohen's Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) (Cohen et al., 1983; Cohen & Williamson, 1988): The adapted version of Herrero and Meneses (2006) of 4 Likert scale items with 4 response options (0: never - 4: always) was used. The Cronbach's alpha reliability of the scale is .74 (Ruisoto et al., 2020). In this research to determine reliability, Guttman's Two-Halves analysis was used, which weights the correlation that exists between the score obtained from the first and second half of the items of the instrument to determine the internal consistency (Kerlinger & Lee, 2002). A correlation of .526 was obtained for stress perception and .565 for stress coping.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (Kessler & Mroczek, 1994): The version adapted to the Ecuadorian population was used, consisting of 10 items with a 5-level Likert scale (1: never - 5: always); it has an adequate internal consistency, α = .90 (Larzabal et al., 2020).

Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff, 1995): Adapted to Spanish, in a 29-item version (Díaz et al., 2006) with 6 answer options (1: totally disagree - 6: totally agree). The instrument is composed of 6 dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, mastery of the environment, life purpose, and personal growth. It has an internal consistency of α= .90 (Moreta et al., 2017). The internal consistency in the present study is .89.

Diener Life Satisfaction Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al., 1985, Spanish version of Vázquez et al., 2013): The version adapted to the Ecuadorian population was taken as a reference, composed of 5 items with a Likert scale of 7 levels (1: totally disagree - 7 totally agree); it has a Cronbach's alpha of .81 (Arias & García, 2018).

Procedure

The application of the scales was carried out in May 2021. A questionnaire was created in Google Forms, the link to which was sent to the researchers' contacts through emails and social networks, who in turn forwarded these links requesting participation. Once the responses were registered, they were automatically tabulated in spreadsheets, obtaining 439 observations, and after purging those considered inconclusive or incongruent, the number was reduced to 436.

This project was reviewed and approved by a committee of the graduate unit of the affiliation institution. The participants freely and voluntarily agreed to participate in the research, after accepting the informed consent. They were also instructed that the data were for academic purposes only.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS statistical software version 20. It begins with a descriptive analysis of the scales evaluated. The statistical procedure used for the comparison of means of the perceived stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction scales was ANOVA, given that the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity of variances were met through Levene’s test. Also, ANCOVA was used to find differences between the aforementioned variables, and the educational follow-up covariates groups were formed according to the type of work: face-to-face work, teleworking, and unpaid work.

Results

Comparative analysis according to work modalities

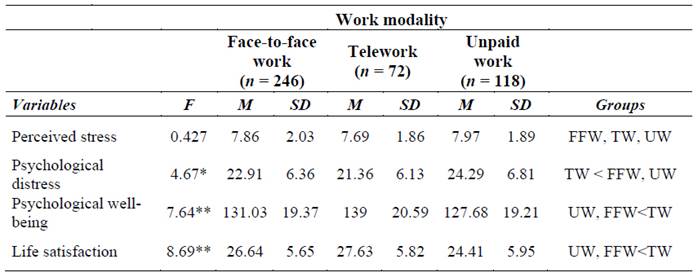

This section presents the descriptive analysis of the direct scores of the variables stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction, as well as the comparative study using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) according to work mode (see Table 1).

Table 1: Comparative analysis of direct PSS-4, K10, Ryff's BP, and SWLS scores according to work modality

Note: 436 observations. *p <. 05; **p < .01. FFW: face-to-face work; TW: telework; UW: Unpaid work

No statistically significant differences were found in total stress. However, in the psychological distress scale, the ANOVA statistic indicated a difference between work modalities. Gabriel-based post hoc tests showed two homogeneous subsets formed (telework; face-to-face work, and unpaid work). The telework group presented lower levels of psychological distress in relation to the groups of face-to-face work and unpaid work, the latter showing higher scores on this scale. Finally, differences were observed in the life satisfaction scale. Post hoc tests based on Gabriel indicated two homogeneous subsets among the work modalities, on the one hand, unpaid and face-to-face work and on the other hand, teleworking with higher levels on that scale. Table 2 presents the comparative analysis of the factors of the perceived stress scale as a function of work mode.

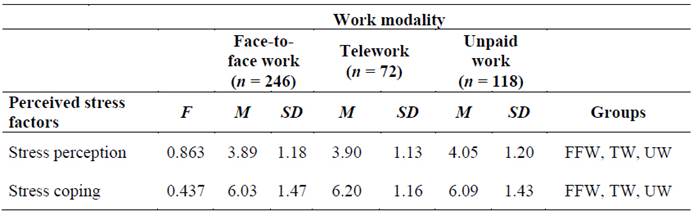

Table 2: Comparative analysis of the factors of the perceived stress scale by work mode

Note: 436 observations. *p <. 05; **p < .01. FFW: face-to-face work; TW: telework; UW: Unpaid work

It was found that there were no statistically significant differences in the factors of stress perception and stress coping according to the work modalities. However, in the analysis of the dimensions of psychological well-being, discrepancies were found between the study groups (see Table 3).

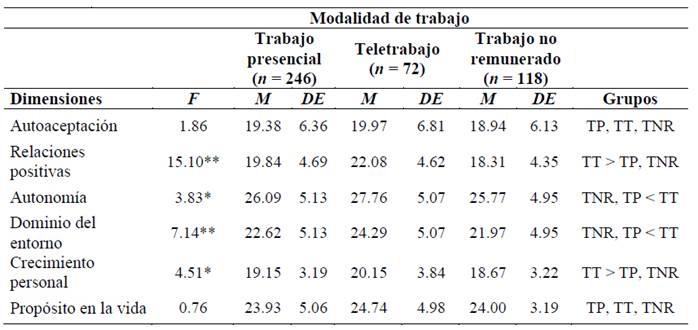

Table 3: Comparative analysis of the dimensions of the psychological well-being scale by work modality

Note: 436 observations. *p <. 05; **p < .01. FFW: face-to-face work; TW: telework; UW: Unpaid work

It was observed that in the dimensions of self-acceptance and purpose in life no statistically significant differences were found between the work modalities. However, in the positive relationships dimension, there were differences in the means between the work modality groups. Gabriel-based post hoc tests indicated that the unpaid work group presented lower levels compared to the other two groups. The telecommuting group reported higher positive relationships. Regarding autonomy, the ANOVA showed statistically significant differences, with the unpaid work group presenting lower levels, unlike face-to-face and teleworking.

In the environment domain dimension, the ANOVA statistic indicated significant differences between the work modality groups. It was found that the unpaid work group had a lower mean than the face-to-face and teleworking groups. In terms of personal growth, there were differences between the groups. Once again, unpaid work showed lower scores in relation to face-to-face work and teleworking, the latter obtaining better scores in this dimension.

Comparative analysis between work modalities and the educational follow-up covariate

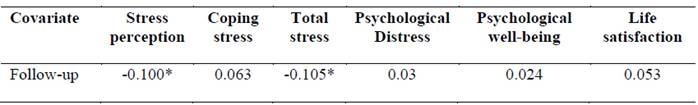

To analyze whether educational follow-up (hours devoted to supporting in school activities) acted as a covariate, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed according to the work modality. For this purpose, the assumptions were analyzed and homogeneity of the regression slopes was found between the covariate (follow-up) and psychological distress, stress perception, stress coping, total stress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction. The regression slopes were reviewed, and it was observed that they have the same direction whose values are very similar. On the other hand, the multicollinearity assumption was checked and it was found that the relationships are less than r= .7, as can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4: Multicollinearity assumption of the PSS-4, K10, Ryff's BP, and SWLS scales with the covariate educational follow-up

Note: *p <. 05

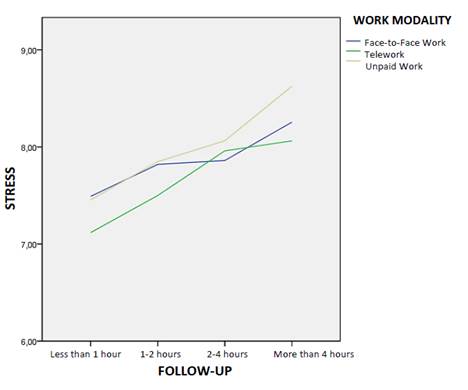

The ANCOVA indicated that, in the case of psychological distress, psychological well-being, life satisfaction, and stress coping, follow-up does not act as a covariate. Instead, in Figure 1, it can be seen how follow-up acted as a covariate in perceived stress (F = 4.92; p = .02) and total stress (F = 5.13; p = .02).

Figure 1: Distribution of the means obtained from the Perceived Stress Scale as a function of the work modalities and the covariate educational follow-up

It was observed that as the hours of educational follow-up increase, stress levels also rise. The unpaid work group scored higher in stress when they spent more than 4 hours a day on this activity. On the other hand, when dedicating less than 1 hour to this function, stress decreased, with the telework group having lower scores.

Discussion

The pandemic is a phenomenon that has generated changes in family routines (Cusinato et al., 2020), especially mothers; children had to move to virtual education, added to the modification of work modalities. Many studies indicate alterations in the mental health of mothers, presenting stress, attributing it to the triple presence (mother-worker and teacher), since 77.5% of mothers are in charge of childcare, 81.9% are in charge of the home, and 73.9% of the participants are in charge of teaching or supporting school activities.

A growing number of studies analyze the impact and negative effects of COVID-19, especially on mothers. However, some of them are qualitative, exploratory, and descriptive, leaving aside the comparative analysis between different work modalities.

The results show that the three work modalities (face-to-face, telework, and unpaid work) present similarities in stress perception and stress coping factors (Table 2) and in the total level of stress (Table 1). A tentative explanation is that participants in general are exposed to similar stressors. Tchimtchoua (2020) points out that mothers have faced sudden changes in routines and social interaction. They are the ones balancing childcare, being at home, their responsibilities, work, and financial and health concerns.

On the other hand, the values show statistically significant differences in the psychological distress scale (Table 1), with emphasis on the unpaid work group. Low or absent income produces higher levels of psychological distress (Capaquira et al., 2020).

Hibel et al. (2021) state that economic cutbacks may be linked to anxious and depressive symptoms, which are intensified by the worry of contracting the virus during work and could be associated with the distress of mothers in face-to-face mode. These factors allow us to think that mothers in telework, with less psychological discomfort, have work and economic stability, decreased risk of contagion, paid the possibility of being close to their children, and generate emotional ties.

The above is consistent with the results of the total scale of psychological well-being (Table 1), with mothers in unpaid work having lower scores about face-to-face work and teleworking. Goldberg et al. (2021) mention that there are better levels of well-being in paid work cases, possibly due to equal conditions, both parents having an economic income, added to sharing household chores and childcare, showing parental co-responsibility. In comparison to unpaid work, due to economic difficulties affects their safety, protection, and psychological well-being, generating anguish and anxiety (Hibel et al., 2021).

However, the study by Calarco et al. (2020), shows that mothers with uninterrupted childcare hours, with less intense pressures, and even job losses, have greater energy and well-being. Unlike mothers who combine their intensive work, accompanied by intense parental pressures, increasing the negative impact generated by parenting and the search for their well-being.

It is appropriate to analyze the dimensions of the psychological well-being scale. There are no statistically significant differences in self-acceptance, probably because they have more experience in parenting (M = 2.29); with a mean age of approximately 38 years, where a condition of maturity is assumed and therefore, greater knowledge and acceptance of themselves.

In the dimension of positive relationships, differences are observed, with mothers in unpaid work showing the lowest levels, which could be because they spend most of their time at home, causing their social relations to be affected or diminished (Janssen et al., 2020).

Statistical differences are also found in the environment domain, with mothers in unpaid work showing lower levels in relation to face-to-face work and teleworking. The first group does not have formal interaction contexts, such as the workplace, which hinders their ability to influence their environment and adjust it to their needs, generating a kind of harmful self-isolation.

Similarly, in the autonomy dimension, there are significant differences, with low levels for mothers in unpaid work, followed by on-site work, and high levels for mothers in telework, as not having their own income limits their willingness to make decisions and achieve independence, given that they have to be dependent on the income of their partner or a family member.

In personal growth, differences are evident, with the unpaid work group showing lower levels in relation to the other modalities. Medina y Fernández (2021), report that women's greater dedication to unpaid activities limits their time to generate their own income and restricts their possibilities for personal growth and time for themselves.

One of the tentative explanations for the results found in relation to the dimension of purpose in life is that existential achievement is not limited to the labor field, but to the fullness of being a mother and forming a home, where economic indicators are insufficient facing the greatness of motherhood despite the burdens and sacrifices that they entail.

Data from the life satisfaction scale indicate low levels in the unpaid work group as opposed to the others, possibly due to job loss or economic dependence. Several studies indicate that people who experience economic difficulties have lower life satisfaction (Conger et al., 2010; Kornrich & Eger, 2016; Möhring et al., 2020).

It was considered appropriate to conduct an analysis with the covariate educational follow-up, given virtual education and the possible addition of a new role for mothers as facilitators of learning. Differences are identified between the groups in terms of stress perception and total stress, due to the increase in stressors and the combination of different roles to be performed (Moscardino et al., 2021).

Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted, as statistically significant differences were found in the variables stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction. In the stress variable, differences are found in the analysis with the educational follow-up covariate. However, it is difficult to compare with other studies due to the limited information on work modalities and study variables.

Although the study has a large sample, it is also necessary to point out a number of limitations. First, it has not been included if any family member or the participant had COVID-19, which may be affecting their quality of life and mental health. Secondly, the mother's level of schooling was not investigated, given that it could be influencing the educational follow-up, causing stress levels, by not having the tools or knowledge of the subjects taught, as well as the socioeconomic level. Razeto's research (2016) shows studies in which low-income families are less able to link with the school and educational follow-up of their children. Third, future studies could consider the presence of children with disabilities or pathologies. According to Ohlbrecht and Jellen (2021), the stress of parents of children with ASD and their emotional well-being were adversely affected during the pandemic as symptomatology intensified as a result of the measures taken by the government to deal with COVID-19. It would also be important to make comparisons between fathers and mothers.

Conclusions

The results of this research have shown statistically significant differences between work modalities, with mothers in unpaid work reporting higher levels of psychological distress, low scores in psychological well-being, and life satisfaction about the other groups, while mothers in telework present better emotional stability. As for stress, differences were found when analyzed with the covariate educational follow-up in the perception of stress and total stress.

It is concluded that work modality is related to psychological well-being, psychological distress, and satisfaction of mothers who have children studying, but not stress. However, when the covariate of monitoring (hours of monitoring of the child's classes) is included with the work modality, it does generate statistically significant differences in stress and stress perception (but not in coping, the ability to cope is independent of the feeling of stress), that is, educational monitoring does not "generate" well-being, discomfort or satisfaction, but does generate stress.

In a way, any work modality, added to the task of educational follow-up, generates stress but does not "affect" discomfort, well-being, or satisfaction; it could be assumed that mothers are not affected by the well-being or discomfort of helping children academically in addition to their own work, but it does generate stress, being the unpaid work group those who report higher levels of stress as the hours of educational follow-up increase.

Therefore, it is concluded that there are statistically significant differences in stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction among work modalities in mothers.

REFERENCES

Arias, P. & García, F. (2018). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la vida en población ecuatoriana adulta. Pensamiento Psicológico, 16(2), 21-29. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI16-2.ppes [ Links ]

Calarco, J., Meanwell, E., Anderson, E., & Knopf, A. (2020). "Let’s Not Pretend It’s Fun": How Disruptions to Families’ School and Childcare Arrangements Impact Mothers’ Well-Being. SocArXiv Papers, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/jyvk4 [ Links ]

Camacho, J. (2021). El teletrabajo, la utilidad digital por la pandemia del COVID-19. Revista Latinoamericana de Derecho Social, (32), 125-155. [ Links ]

Cameron, E., Joyce, K., Delaquis, C., Reynolds, K., Protudjer, J., & Roos, L. (2020). Maternal psychological distress & mental health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, (276), 765-774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.081 [ Links ]

Capaquira, J., Arias, W., Muñoz, A., & Rivera, R. (2020). Malestar Psicológico, Relación con la Familia y Motivo de Consulta en Mujeres de Arequipa (Perú). Atención Familiar, 27(2), 81-85. https://doi.org/10.22201/facmed.14058871p.2020.2.75680 [ Links ]

Castillo, R. (2015). Empleo y condición de actividad en Ecuador. Coordinación General Técnica de Innovación en Métricas y Análisis de la Información, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2015/02/Empleo-y-condici%C3%B3n-de-actividad-en-Ecuador.pdf [ Links ]

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385-396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 [ Links ]

Cohen, S. & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. En S. Spacapan y S. Oskamp (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Health (pp. 31-67). Sage. [ Links ]

Conger, R., Conger, K., & Martin, M. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(3), 685-704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [ Links ]

Corte Constitucional del Ecuador. (2020). Decreto N.º 1017. https://www.defensa.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2020/03/Decreto_presidencial_No_1017_17-Marzo-2020.pdf [ Links ]

Cusinato, M., Iannattone, S., Spoto, A., Poli, M., Moretti, C., Gatta, M., & Miscioscia, M. (2020). Stress, resilience, and well-being in Italian children and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228297 [ Links ]

De Clercq, D. & Brieger, S. (2021). When discrimination is worse, autonomy is key: how women entrepreneurs leverage job autonomy resources to find work-life balance. Journal of Business Ethics, 177(3), 665-682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04735-1 [ Links ]

Díaz, D., Rodríguez, R., Blanco, A., Moreno, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2006). Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema, 18(3), 572-577. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Wolsic, B., & Fujita, F. (1995). Physical Attractiveness and Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 120-129. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.120 [ Links ]

Espíndola, J., Morales, F., Díaz, E., Pimentel, D., Meza, P., Henales, C., Carreño, J., & Ibarra, A. (2006). Malestar psicológico: algunas de sus manifestaciones clínicas en la paciente gineco-obstétrica hospitalizada. Perinatología y Reproducción Humana, 20(4), 112-122. [ Links ]

Esteves, A. (2020). El impacto del COVID-19 en el mercado de trabajo de Ecuador. Mundos Plurales - Revista Latinoamericana de Políticas y Acción Pública, 7(2), 35-41. https://doi.org/10.17141/mundosplurales.2.2020.4875 [ Links ]

Gaxiola, J. & Palomar, J. (Coords.). (2016). El Bienestar Psicológico: Una mirada desde Latinoamérica. Quartuppi. [ Links ]

Goldberg, A., McCormick, N., & Virginia, H. (2021). Parenting in a pandemic: work-family arrangements, well-being, and intimate relationships among adoptive parents. Family Relations, 70(1), 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12528 [ Links ]

Gordon, S. (2021). Mujeres , trabajo doméstico y COVID-19: explorando el incremento en la desigualdad de género causada por la COVID-19. Psicología Iberoamericana, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.48102/pi.v29i1.399 [ Links ]

Herrera, B., Cárdenas, B., Tapia, J., & Calderón, K. (2021). Violencia intrafamiliar en tiempos de COVID-19: una mirada actual. Polo Del Conocimiento, 6, 1027-1038. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v6i2.2334 [ Links ]

Herrero, J. & Meneses, J. (2006). Short Web-based versions of the perceived stress (PSS) and Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD) Scales: a comparison to pencil and paper responses among Internet users. Computers in Human Behavior, (22), 830-848. [ Links ]

Hibel, L., Boyer, C., Buhler-Wassmann, A., & Shaw, B. (2021). The psychological and economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latina mothers in primarily low-income essential worker families. Traumatology, 27(1), 40-47. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000293 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. (2020, febrero 21). El INEC también genera estadísticas de trabajo no remunerado. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/el-inec-tambien-genera-estadisticas-de-trabajo-no-remunerado/ [ Links ]

Isch, A. (2020). Acuerdo Ministerial N.º MDT-2020-181. Ministerio del Trabajo. https://www.trabajo.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/AM-MDT-2020-181-TELETRABAJO-14.09.2020-signed.pdf?x42051 [ Links ]

Janssen, L., Kullberg, M., Verkuil, B., van Zwieten, N., Wever, M., van Houtum, L., Wentholt, W., & Elzinga, B. (2020). Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS ONE, 15(10), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240962 [ Links ]

Kerlinger, F. & Lee, H. (2002). Investigación del comportamiento. McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. & Mroczek, D. (1994). Final Versions of our Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale. https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=2987d9ec-beca-4fc6-a58a-a6ede4f532b3 [ Links ]

Kornrich, S. & Eger, M. (2016). Family life in context: men and women’s perceptions of fairness and satisfaction across thirty countries. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, (23), 40-69. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxu030 [ Links ]

Larzabal, A., Ramos, M., Jaramillo, A., & Hong, A. (2020). Propiedaes psicométricas de la escala de malestar subjetivo de Kessler (K10) en adultos. CienciaAmérica, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.33210/ca.v9i3.265 [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. & Folkman, S. (1986). Estrés y procesos cognitivos. Evaluación, afrontamiento y consecuencias adaptativas. Martínez Roca. [ Links ]

Llanes, N. & Pacheco, E. (2021). Maternidad y trabajo no remunerado en el contexto del Covid-19. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, (1), 61-92. [ Links ]

Lyttelton, T., Zang, E., & Musick, K. (2020, agosto 4). Before and during COVID 19: Telecommuting, work-family conflict, and gender equality. Council on Contemporary Families. https://sites.utexas.edu/contemporaryfamilies/2020/08/03/covid-19-telecommuting-work-family-conflict-and-gender-equality/ [ Links ]

Manrique, A. & De Jesús, M. (2020).The COVID-19 Pandemic and ethics in Mexico through a gender lens. Investigación Bioética, 17(4), 613-617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10029-4 [ Links ]

Martiny, S., Thorsteinsen, K., Parks-Stamm, E., Olsen, M., & Kvalø, M. (2021). Children’s well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic : relationships with attitudes, family structure , and mothers’ well-being. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19(5), 711-731. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1948398 [ Links ]

Mayordomo, T., Sales, A., Satorres, E., & Meléndez, J. (2016). Bienestar psicológico en función de la etapa de vida, el sexo y su interacción. Pensamiento Psicológico, 14(2), 101-112. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI14-2.bpfe [ Links ]

Mayorga, V. & Llerena, F. (2021). Rol de la familia en la educación virtual del nivel inicial. Revista Científica Retos de la Ciencia, 5(e), 23-41. [ Links ]

Medina, E. & Fernández, M. (2021). La autonomía económica de las mujeres latinoamericanas. Apuntes Del Cenes, 40(72), 181-204. https://doi.org/10.19053/01203053.v40.n72.2021.12606 [ Links ]

Möhring, K., Naumann, E., Reifenscheid, M., Wenz, A., Rettig, T., Krieger, U., Friedel, S., Cornesse, C., & Blom, A. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and subjective well-being: longitudinal evidence on satisfaction with work and family. European Societies, (23), 601-617. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1833066 [ Links ]

Moreta, R., Gaibor, I., & Barrera, L. (2017). El bienestar psicológico y la satisfacción con la vida como predictores del bienestar social en una muestra de universitarios ecuatorianos. Salud & Sociedad, 8(2), 172-184. https://doi.org/10.22199/S07187475.2017.0002.00005 [ Links ]

Moscardino, U., Dicataldo, R., Roch, M., Carbone, M., & Mammarela, I. (2021). Parental stress during COVID-19: a brief report on the role of distance education and family resources in an Italian sample. Current Psychology, 40(11), 5749-5742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01454-8 [ Links ]

Ohlbrecht, H. & Jellen, J. (2021). Unequal tensions: the effects of the coronavirus pandemic in light of subjective health and social inequality dimensions in Germany. European Societies, (23), 905-922. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1852440 [ Links ]

Padros, F., Gutiérrez, C., & Medina, M. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida (SWLS) de Diener en población de Michoacán (México). Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, (33), 223-232. https://doi.org/10.12804/apl33.02.2015.04 [ Links ]

Razeto, A. (2016). El involucramiento de las familias en la educación de los niños. Cuatro reflexiones para fortalecer la relación entre familias y escuelas. Páginas de Educación, 9(2), 190-216. https://doi.org/10.22235/pe.v9i2.1298 [ Links ]

Ruisoto, P., López-Guerra, V., Paladines, M., & Vaca, S. (2020). Psychometric properties of the three versions of the Perceived Stress Scale in Ecuador. Physiology & Behavior, 224(113045). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113045 [ Links ]

Ryff, C. & Keyes, C. (1995). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 69(4), 719-727. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719 [ Links ]

Tchimtchoua, A. (2020). An analysis of mother stress before and during COVID-19 pandemic: The case of China. Health Care for Women International, (41), 1349-1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2020.1841194 [ Links ]

Vázquez, M., Bonilla, W., & Acosta, L. (2020). La educación fuera de la escuela en época de pandemia por Covid 19. Experiencias de alumnos y padres de familia. Revista Electrónica Sobre Cuerpos Académicos y Grupos de Investigación, 7(14), 111-134. [ Links ]

Vázquez, C., Duque, A., & Hervás, G. (2013). Satisfaction with Life Scale in a representative sample of Spanish adults: validation and normative data. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16(82), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.82 [ Links ]

Xue, B. & McMunn, A. (2021). Gender differences in unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK Covid-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE , 16(3), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247959 [ Links ]

How to cite: Valle Pico, M. I. & Larzabal Fernández, A. (2022). Stress, psychological distress, psychological well-being and life satisfaction according to work modalities in mothers of families. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2794. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2794

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M. I. V. P. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; A. L. F. in a, c, e.

Received: January 20, 2021; Accepted: October 15, 2022

texto en

texto en