Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.16 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2257

Original Articles

Psychological abuse, self-esteem and emotional dependence of women during the COVID-19 pandemic

1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil, tamyres.tomaz1@gmail.com

2 Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil

Violence against women, like COVID-19, is a pandemic phenomenon that affects all social strata. The aim of this study was to understand the relations between psychological abuse, self-esteem, and emotional dependency in women during the pandemic, from the perspective of the Theory of Traumatic Bonding. The sample included 222 women, the majority heterosexual (76.6 %), dating (53.3 %) or married (44.1 %). The results showed that the greater the psychological abuse, the lower the self-esteem and the greater the dependence on the spouse. An alternative model has also been confirmed, demonstrating that the greater the dependency, the greater the susceptibility to maintaining abusive relationships, and the low self-esteem intensifies this cyclical process. In addition, we observed that women who live full-time with partners during social isolation showed greater psychological abuse and exclusive dependency.

Keywords: psychological abuse; self-esteem; COVID-19; emotional dependence; partner violence

A violência contra a mulher assim como a COVID-19 é um fenômeno pandêmico, que atinge todas as camadas sociais. O objetivo deste estudo foi conhecer as relações entre o abuso psicológico, a autoestima e a dependência emocional de mulheres durante a pandemia, sob a ótica da teoria do vínculo traumático. Contamos com 222 mulheres, a maioria heterossexual (76,6 %), namorando (53,3 %) ou casadas (44,1 %). Os resultados demonstraram que quanto maior o abuso psicológico, menor é a autoestima e maior a dependência do cônjuge. Um modelo alternativo também foi confirmado, demonstrando que quanto maior a dependência, maior a susceptibilidade em manter relacionamentos abusivos e a baixa autoestima intensifica esse processo de caráter cíclico. Além disso, observamos que mulheres que convivem em tempo integral com parceiros durante o isolamento social apresentaram maior abuso psicológico e dependência exclusiva.

Palavras-chave: abuso psicológico; autoestima; COVID-19; dependência emocional; violência por parceiro íntimo

La violencia contra las mujeres, como la COVID-19, es un fenómeno pandémico, que afecta a todos los estratos sociales. El objetivo de este estudio fue comprender las relaciones entre el maltrato psicológico, la autoestima y la dependencia emocional de las mujeres durante la pandemia, desde la perspectiva de la teoría del vínculo traumático. La muestra se conformó por 222 mujeres, la mayoría heterosexuales (76.6 %), novias (53.3 %) o casadas (44.1 %). Los resultados mostraron que a mayor abuso psicológico, menor autoestima y mayor dependencia del cónyuge. También se confirmó un modelo alternativo, demostrando que a mayor dependencia, mayor susceptibilidad a mantener relaciones abusivas y la baja autoestima intensifica este proceso cíclico. Además, se observó que las mujeres que convivieron a tiempo completo con sus parejas durante el aislamiento social presentaron mayor abuso psicológico y dependencia exclusiva.

Palabras clave: abuso psicológico; autoestima; COVID-19; dependencia emocional; violencia de pareja

The Severe Acuter Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2), which spread the COVID-19, triggered the pandemic period worldwide. In addition to the manifestation of symptoms that caused the death of thousands of people (UN Women, 2020), there was also an increase in cases of violence in this period, especially against women who were in full-time isolation (Boserup et al., 2020). After the lockdown (period of isolation), countries such as France, Argentina, and Spain recorded a 30% increase in cases of violence as compared to previous months (UN Women, 2020). In Brazil, there was a decrease in the registered cases, that is, an underreporting of cases of violence; on the other hand, there was an increase in the number of feminicides during this period (Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP), 2020). This may mean that women are unable to denounce their partners, thus increasing the lethal risk to their lives. This is because acts of psychological abuse often occur in conjunction with acts of physical and/or sexual abuse by intimate partners (World Health Organization (WHO), 2018).

There are several types of violence against girls and women in these private spaces, such as physical and psychological violence, sexual abuse, and behavioral control (Godin, 2020; Sandler, 2020; UN Women, 2020).

Our study focused precisely on psychological abuse, defined as a means of intimidating or threatening a partner, forcing her into isolation from friends, family, and/or work, in order to cause harm to her emotional well-being (WHO, 2018). For Porrúa-García et al. (2016) and Rodriguez-Carballeira et al. (2014), this type of abuse is divided into: direct strategies - which affect cognition, emotion, and behaviors -, and indirect strategies - which act through manipulation, coercion, and pressure. These mechanisms do not happen separately, but jointly, which is why psychological abuse is as serious as physical abuse. Many women undergo psychological abuse and are not even aware that they are being violated, because this type of abuse happens in a subtle and invisible way. Research by Aizpurua et al. (2021), Godin (2020) and Sandler (2020) identified that the more behavioral control the male partner has over his female partner, the more probable psychological abuse is. Therefore, this form of control becomes an indirect strategy on the partner's behavior through pressure and manipulation.

Abuses are part of a continuous process that occurs at all times of the year, because intimate partner violence is structural and may derive from the bond instabilities during the period of childhood (Bowlby, 1969; Dutton & Painter, 1993; Dutton & White, 2012), that is, caused by traumatic bonding (Dutton & Painter, 1993). This traumatic bonding is the notion that strong emotions of a good or bad treatment, intermittently applied by the caregiver, may lead to insecurity, and this contributes for developing the feeling of attachment. Such deviations of insecure attachment are manifested in intimate relationships through emotional dependency, based on idealization and submission to the partner's will, diminishing self-worth due to low self-esteem (Petruccelli et al., 2014).

In the current pandemic scenario, the most serious consequences of abusive relationships are visible, such as physical abuse and, in some cases, feminicide. This leads to cases of psychological abuse being underreported (FBSP, 2020) It is precisely on this crucial point that we focus our research, because we analyze whether psychological abuse has a direct relation with emotional dependency, making women more susceptible to their partners' wills due to this traumatic bonding. In addition, we analyze the role of self-esteem in the relationship between psychological abuse and partner emotional dependency. We tested, in addition to this model, an alternative model in which dependency is a predictor of psychological abuse, and this relationship is mediated by self-esteem. This model is also plausible, since this process happens in a circular (cyclic) way. After all, the more dependent women are, the more they will remain in the abusive relationship, accepting all forms of manipulation due to emotional dependency (Dutton & Painter, 1981; Walker, 1979).

A key to the process of acceptance and maintenance of violence

The theory of traumatic bonding is based on the theoretical assumptions of the attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969), learned helplessness theory (Seligman, 1975), and cycle of violence theory (Walker, 1979). It consists of psychosocial structures that consider both social and psychological factors, which are important in the process of understanding intimate partner violence (Dutton & Painter, 1981). A social factor is understood as the entire historical trajectory of people's lives (e.g., exposure to violence, especially in the context of COVID-19, educational level), derived from patriarchal societal relations (Dutton & Painter, 1981; Walker, 1979). A personal factor is understood as all factors related to the person (e.g., age, gender, personality, self-esteem, emotional dependency, among others) (Dutton & Painter, 1981). Thus, the key to understanding the permanence of women in their abusive relationships possibly lies in two fundamental parameters: the power differential and the intermittency of abuse (Dutton & Painter, 1981). The power differential is related to hierarchy in romantic relationships. As the victim perceives these demonstrations of power, operationalized through violence, the more negative her self-assessment will be (i.e., low self-esteem), and the less likely to leave this relationship she will be, increasingly needing a dominator (Dutton & Painter, 1993).

Self-esteem is defined as a set of feelings and thoughts about oneself (Sbicigo et al., 2010). Women victims of violence can express it negatively with their self-esteem (Bigizadeh et al., 2021; Paiva et al., 2017). Self-esteem may also act as a moderator in the relationship to increase symptoms of depression and anxiety (Costa & Gomes, 2018) and as a mediator in the relation between domestic violence and the symptoms of depression (Kim & Kahng, 2011). The fear of being alone and a need to always please the partner tend to lower self-esteem and increase emotional dependency (Urbiola et al., 2017), which, in turn, may increase beliefs that legitimize intimate partner violence. Dependency strengthens the bond between the person in a lower condition and the person in an upper condition (Dutton & Painter, 1993). In addition, the dependent woman has greater self-denial, that is, reality denial, once she believes the relationship has no problems (Moral & Ruiz, 2009).

As for the intermittency of abuse, it is explained by the phases of abuse: 1) tension build up; 2) acute battering; 3) contrition, described by Walker’s cycle of violence theory (1979). Dutton and Painter (1981) explain that these phases serve to connect the victim of violence to her abuser as a “miraculous bonding”. Thus, it becomes an ambivalence between the idealized husband and the abusive husband. Even after the marital separation, it is common for women to return to have contact with their partners, having difficulties in leaving abusive relationships behind (Dutton & Painter, 1981; 1993). This is partly because they are reinforced by society that their spouses will change, and, for that reason, they always deserve other chances for this change to occur. This phase is conceptualized as “contrition” (Walker, 1979). With this, reinforcement occurs intermittently between negative and positive emotions in the relationship (Dutton & Painter, 1981). In such relationships, in which physical and psychological abuse are present, the demonstrations of power displayed by body marks and threats to her dignity and that of her children render the victim powerless in the face of these situations. Victims, in turn, attach themselves to these relationships as homeostasis, a process of maintaining internal balance (Dutton & Painter, 1993).

In these cases, emotional attachment is nothing more than a cognitive distortion, characterized by the use of behavioral strategies that aim to keep both (victim and abuser), even if unintentionally, in the situation of intimate partner violence (De Young & Lowry, 1992). The dominator may use indirect strategies designed to emphasize the submission and vulnerability of the dependent person. He can also use direct strategies, manipulating and strengthening the bonds, in order to diminish the feeling of abandonment, either assertively or aggressively (e. g., intimidation, keeping the victim in a situation of emotional dependency) (Bornstein, 2006).

Emotional dependency is configured as a pattern of needs not emotionally met, which produces inadequate dysfunctional responses in interpersonal relationships (Urbiola et al., 2017). Affective dependents let other people decide for them, accepting any condition imposed by the other (Moral & Ruiz, 2009). It functions as a need that is only relieved by the presence of the partner (Bution & Wechsler, 2016). Individuals, in general, lose their identities to live according to the other (Dutton & Painter, 1981), and they even become more accepting of abuse in relationships (Petruccelli et al., 2014).

For Rathus and O'Leary (1997), emotional dependency is divided into three types: anxious attachment, exclusive dependency, and emotional dependency. Anxious attachment is identified as an anxiety out of fear of separation from the spouse, caused by feelings of abandonment and weak affective attachment. Exclusive dependency is identified as an exclusive dedication to the partner, as if there were no other people who mattered more to them than their partner. And emotional dependency is characterized as a need supplied by the partner, which requires the person to stay with the partner at all costs, even if this is the aggressor. Our research focuses precisely on these aspects of emotional dependency as a contributing factor to the maintenance of abusive relationships.

In this regard, we aimed to know the relations between psychological abuse, self-esteem, and emotional dependency in women during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we aimed to analyze the profile and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Therefore, this study focused on the psychosocial implications of the pandemic context in the lives of Brazilian women.

The impacts of the pandemic on marital relationships are still unknown. Our hypotheses are guided by theoretical contributions that justify the need for tests to prove the phenomena we seek to answer.

The following hypotheses were tested: (1) We expect that psychological abuse can positively predict emotional dependency and that this process is mediated by self-esteem, based on the theory of traumatic bonding. We justify our hypothesis based on the argument that psychological abuse is a traumatic event that causes a decrease in self-esteem in the victims, thus contributing to a greater attachment, which is characterized as emotional dependency. The more abuse a woman suffers, the more she needs to have a partner, becoming dependent on this abusive relationship (Amor & Echeburúa, 2010). In this regard, a study by Moral et al. (2017) checked the existing relation between violence in dating, emotional dependency, and self-esteem in adolescents and young adults. As a result, it was shown that there was greater emotional dependency and lower self-esteem in those victimized as compared to those not victimized. Therefore, we specifically aimed that psychological abuse is also a predictor of emotional dependency and self-esteem in adult women.

(2) Given the cyclical nature of the processes of psychological abuse and emotional dependency, we expect that an alternative model is also possible. In this sense, we specifically aim that emotional dependency can also positively predict psychological abuse and that this relation is mediated by self-esteem. This model has not yet been tested by this theory, although the woman victim of abuse remains in this abusive relationship due to emotional dependency created from the traumatic bonding, which can either be derived from exposure to violence of important people (e.g., father, mother) and from the observed experience itself.

(3) We also predict that the relation between psychological abuse and emotional dependency mediated by self-esteem occurs depending on the age of the woman. We specifically hypothesize that this relational process occurs in younger women. Study such as that of Moral et al. (2017) showed that women who were in high school were more victimized and were more emotionally dependent on their partners as compared to women who were in higher education. The WHO (2018) stated that about one-third of girls and women aged 15-49 have already suffered some form of domestic violence. Therefore, age can be an important variable in the relations between these constructs.

(4) And finally, we specifically aim for significant differences in emotional dependency - in the specific factors anxious attachment, exclusive dependency, and emotional dependency - and in psychological abuse in women who were living full-time with their partners, as well as those who were living with their partner during the social isolation recommended by health agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

Participants

The sample included 222 women aged between 18-66 (M= 27.9; SD= 7.80), most of them dating (53.3 %) or married (44.1 %). Most participants claimed to be heterosexual (76.6 %) and were living with their partner (61.4 %), living together full time (45.5 %) or part time (33.8 %). Regarding schooling, the majority (35.6 %,) had incomplete higher education. Most claimed to be Catholic (35.1%), and their income was between 1 and 3 minimum wages (34.2 %).

The inclusion criteria were being a woman aged over 18 years and able to understand the items of the instruments. We also asked whether the participants experienced any violence during the period they were socially isolated due to the pandemic. Among the abuses, 14 women (6.3 %) reported suffering psychological abuse (n = 10) and more than one form of abuse (n= 4), including physical, sexual or patrimonial violence. This study and sample size (N= 222) provided 80 % testing power (average effect = 0.88; equivalent a η2 p= 0,05), calculated by WebPower (Schoemann et al., 2017).

Instruments

Scale of Psychological Abuse in Intimate Partner Violence (EAP-P, in Portuguese), developed by Porrúa-Garcia et al. (2016), validated for Brazil by Paiva et al. (2020). The measure is composed of 19 items distributed initially in 2 factors: 1) Direct strategies of psychological abuse (e.g., “My partner has his or her own interpretation of things that have affected us”); and 2) Indirect strategies of psychological abuse (e.g., “My partner stopped me from doing activities I liked”). This scale can also be evaluated in a one-factor way because it has been validated as a two-factor (α = 0,92). A Likert model was used assessing how often the strategies are committed in women, in a response pattern between 0 (never) and 4 (always).

Spouse-Specific Dependency Scale for Women, developed by Rathus and O’Leary (1997), validated for Brazil by Paiva et al. (2021). It is composed of 30 items initially grouped into 3 factors: 1) Anxious attachment (e.g., “I get anxious if I think my partner is upset with me”); 2) Emotional dependency (e.g., “I like my partner because he/she is protective and understanding”); and 3) Exclusive dependency (e.g., “I rarely sleep if my partner is not with me”). To assess this construct, we summed all the subscales forming a second-order factor of general emotional dependency (α = 0.92). The respondents used a Likert-type scale between 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree).

Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale (SISES), developed by Robins et al. (2001). It has evidence of convergent validity with the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (CSR) in a Brazilian sample (Pimentel et al., 2018). The instrument consists of only 1 item (“I have self-esteem”). Participants respond on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not common for me) to 7 (very common for me).

And a sociodemographic questionnaire with the information: age, gender, marital status, sexual orientation, income, religion, schooling, and how much time they spend with their partner, and whether they live with their partner full-time during the pandemic. Furthermore, we asked if the participants were in social isolation (yes or no) and if during social isolation they are experiencing any kind of abuse (yes or no), if yes, what kind of violence.

Procedures

Initially, the study was submitted to the approval of the Ethics Committee (CAEE: 09344918.5.0000.5188; document nº 4.098.062). Participation was initiated after the participants agreed to the Informed Consent Form. The collection was conducted online via social media during the vertical isolation period (June 17 to July 5, 2020). The survey link was posted on social networks such as Instagram and women’s groups on Facebook. Respondents were informed that the survey followed the recommendations of Resolution 510/16 of the National Health Council. The instruments were presented to the participants following the logic of the model. First, the psychological abuse scale was presented, then the self-esteem scale, and finally the emotional dependency scale. At the end of the instrument, the complaint number for violence against women was made public, and the researchers also provided their contact for any further questions.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software (version 22.0) and the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017). Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the sample in the constructs evaluated. Also, Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to verify the normal distribution of data. Violations of normality for parametric tests were corrected by bootstrapping with 1000 simulations. To test the hypotheses, inferential statistics were performed, such as Pearson’s correlation analysis, simple mediation (model 4), moderate mediation (model 15) and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), to compare the scores in relation to the time of cohabitation and the participants living or not living with a partner.

Results

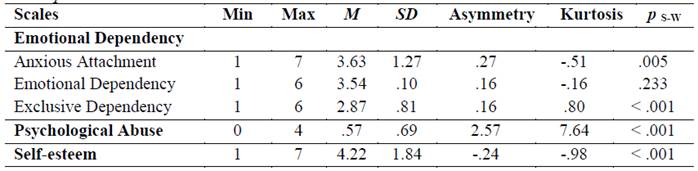

We performed descriptive statistics to analyze the mean and standard deviations of the scales in the sample. We also analyzed the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (Ghasemi & Zahediasl, 2012) to assess the distribution of the data in the sample. The more asymmetry, the further away from zero the factor will be, and the smaller the kurtosis, the less flattened the frequency curve of responses will be. We observed that emotional dependency (in all its factors) and self-esteem had asymmetry close to 0 and the most flattened curve. As for psychological abuse, it had an asymmetry more distant from 0 and more elongated kurtosis. Thus, we consider emotional dependency and self-esteem scores to have approximately normal distributions and psychological abuse to have an asymmetric distribution (Table 1). With this, all the techniques implemented below were conducted with bootstrapping of 1000 simulations for normality correction.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics

Note: M: mean; SD: standard deviation; p S-W: p-value of Shapiro-Wilk test.

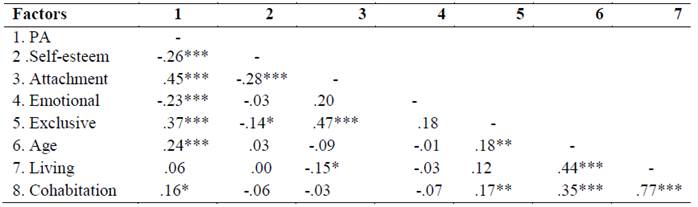

To find out if the variables have a relation between themselves, we performed a two-tailed Pearson correlation (Table 2). Psychological abuse was correlated with all factors of emotional dependency, as well as correlated with self-esteem, age of the participant and time of cohabitation with the partner. Thus, we infer that the greater the psychological abuse experienced, the lower the self-esteem and the greater the exclusive dependency and anxious attachment in the participants. The emotional dependency factor correlated negatively with psychological abuse, indicating that the greater the psychological abuse, the lower the emotional dependency. The time of cohabitation also has a positive correlation with psychological abuse, that is, the longer the time spent with the partner, the more psychological abuse the participant may suffer.

Table 2: Correlations between the constructs

Notes: PA: Psychological Abuse. ** p > 0,001; * p > 0,05.

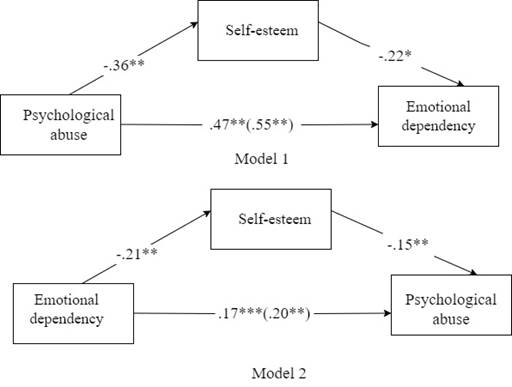

For a more robust analysis, we tested hypotheses 1 and 2 through simple mediation models. In this model we grouped the factors of emotional dependency, as these formed the second-order factor in order to assess the phenomenon of emotional dependency in general. The results are shown in Figure 1. In model 1, psychological abuse (PA) significantly predicted emotional dependency (ED) mediated by self-esteem (R² = 0.14). The direct effect (b= 0.47; SE= 0.11; p< 0.001; CI 95%: 0.25; 0.68) of PA on ED was lower than the total effect (b= 0.55; SE= 0.20; p< 0.001; CI 95%: 0.34; 0.75). The significant indirect effect (b= 0.08; SE= 0.03; 95% CI 0.02; 0.15) showed that the indirect relation also exists, through a partial mediation. In the alternative model 2, ED predicted PA mediated by self-esteem (R² = 0.15). The direct effect (b= 0.17; SE= 0.04; p< 0.001; CI 95%: 0.09; 0.25) was lower than the total effect (b= 0.20; SE= 0.04; p< 0.001; CI 95%: 0.13; 0.28). The indirect effect was significant (b= 0.03; SE= 0.01; CI 95%: 0.01; 0.06), also indicating a partial mediation. Thus, hypotheses 1 and 2 were confirmed. There is an indirect relation between the constructs through self-esteem.

An age-moderate mediation analysis was performed with model 1 to test hypothesis 3. The results showed a statistically significant interaction between age and self-esteem (b= 0.02; SE= 0.01), all at level p= 0.04, so that the indirect effect of mediation occurred only for women aged up to 33 years (b= 0.13; SE= 0.05; CI 95%: 0.05; 0.22), but not for women over 34 (b= 0.04; SE= 0.04; IC 95%: -0.03; 0.11). Thus, in women over 34 years of age, emotional dependency was more related to psychological abuse. Whereas in women below the age of 34, the reduction in self-esteem indirectly led to a stronger prediction of psychological abuse over emotional dependency.

We assessed whether there were statistically significant differences in the isolated factors of emotional dependency, regarding the time of cohabitation with the partner, and whether the participants were living with their partners during the pandemic period. We found statistically significant differences regarding the time of cohabitation during social isolation in psychological abuse (F(2.222) = 3.93; p= 0.021) and in exclusive dependency (F(2.219) = 4.86; p= 0.009). Multiple comparisons with Tukey's correction showed that women who live full-time with their spouse (M= 1.20; SD= 1.36) reported greater psychological abuse when compared to those who did not live together (M= 0.55; SD= 0.49), all at level p= 0.018. In addition, a lower exclusive attachment was observed in women who did not live together with the partner (M= 2.48; SD= 0.83) when compared to those who live full-time (M= 2.97; SD= 0.90), all at p= 0.023 and partial (M = 2.94; SD = 1.02), all at level p= 0.009. There was also a difference in relation to living with a partner (F(1. 221) = 5.59; p= 0.019) in anxious attachment. In women who were not living with their partner during social isolation, greater anxious attachment occurred (M= 3.87; SD= 1.23) when compared to those who were living with them (M= 3.46; SD= 1.27). Thus, there is evidence that the time of cohabitation and the fact of living with a partner during social isolation positively related to the psychological abuse suffered, exclusive dependency, and anxious attachment of women.

Discussion

Our goal was to apply the Theory of Traumatic Bonding (Dutton & Painter, 1981) to understand the process of victims of violence in remaining in abusive relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our first hypothesis rested on the fact that women who suffer from psychological abuse decreased their self-esteem and consequently increased the emotional dependency on their partner. Our first hypothesis was corroborated through model 1, by showing that traumatic bonding - represented in the present study by psychological abuse - had a direct relation with emotional dependency, as well as being mediated by negative self-esteem. That is, women suffering from psychological abuse can either maintain an emotional dependency without needing a mediator, or they can legitimize the acceptance of psychological abuse through negative self-esteem.

This data is still little explored, although there are studies that focus on the relation between emotional dependency and violence from the perspective of the investment model (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992), which show that people remain in the relationship, even dissatisfied, for they have a need to fulfill that cannot be gratified in other ways. This need is called emotional dependency, which tries to fill in a distorted way what is not gratified in any way if the person is not with the partner exclusively (Bornstein, 2006; Bution & Wechsler, 2016). And this can be an important step to understand the process of remaining in abusive relationships (Amor & Echeburúa, 2010; Rathus & O’Leary, 1997).

However, when assessing the preliminary correlations between the constructs, we observed that only anxious attachment and exclusive dependency correlated positively and more strongly with psychological abuse. The emotional dependency factor, contrary to expectations, correlated negatively and with a coefficient of low magnitude. This result may have occurred due to issues related to the content of the items of the Spouse-Specific Dependency Scale for Women, validated by Paiva et al. (2021), which was used in this study. It shows that most of its items expose a more positive and even romanticized connotation of emotional dependency, such as items 18 (“My partner is the only one who really understands me”); 21 (“I like my partner because he/she is understanding”); 24 (“I prefer to face the adversities of life with my partner by my side”). Thus, the suggestion is that evidence of more positive attachments is negatively correlated with psychological abuse for masking dependency as a form of romantic love.

Regarding attachment, this is a predictor for violence (Rathus & O'Leary, 1997). So, the traumatic bonding becomes stronger as there is attachment in a cyclical or feedback process. And it was precisely in this argument that we established the alternative model (model 2). Thus, we found that dependency also has a direct relation with psychological abuse, and that this relation is also mediated by self-esteem. This indicates that the more dependent women are, the greater the negative impact on self-esteem, and the more vulnerable they are to psychological abuse. This process confirmed our hypothesis 2, being important to understand that the maintenance of psychological abuse also lies on the dependency that women have on their partner, as exposed by the Theory of Traumatic Bonding. With this, we show that the process is cyclical: as the woman suffers violence, she decreases self-esteem and becomes emotionally dependent on her aggressor; as she is emotionally dependent, she continues to accept her abusive suffering by remaining in the relationship. This whole process can represent a chain that is justified by the negative self-esteem for some women, because when we legitimize self-esteem as a mediator, this represents one of the essential elements to be worked on in psychotherapeutic processes.

Women who are in aggressive relationships report more non-voluntary dependency (i.e., they avoid ending the relationship because they think they might experience a worse situation in another relationship; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) than women who have not experienced abusive relationships (Tan et al., 2018). This is because, depending on the level of commitment of these women in their relationships, this can become a tool for maintaining abusive relationships (Bornstein, 2006; Bution & Wechsler, 2016). It is important to highlight that the literature points out that low satisfaction in marital relations in couples with IPV is recurrent and, therefore, it is not necessarily what influences the maintenance or disruption of the violent cycle (Tan et al., 2018). The more committed to the relationship this woman is, the more predisposed she will be to maintain this relationship and the more difficult it will be to get out of it, because she might blame herself for the ending of the relationship. In this sense, emotional dependency manifests itself in different forms: it can be the commitment to the relationship that leads to devotion of the partner (Tan et al., 2018), or it can also lead to anxious attachment of the partner, such as the fear of losing their love object (Bowlby, 1969; Dutton & Painter, 1993; Dutton & White, 2012). This can also vary due to the age groups of women (Petruccelli et al., 2014).

Our study showed that women aged between 18 and 33 had a stronger emotional dependence than women aged over 34. Furthermore, we observed that, in this group of women, the psychological process tested was stronger, that is, a relation between psychological abuse and emotional dependency showed higher coefficients. This data corroborates with our hypothesis 3 and is within the confidence interval proven by WHO (2018), as was also similar to the study conducted by Moral et al. (2017), in which girls up to the age of 18 (high school students) were more victimized, causing them to lower their self-esteem and raising their level of emotional dependency on their partner. In addition, Petruccelli et al. (2014) found in their studies that women aged 32-34 years had higher levels of exclusive dependency and anxious attachment, that is, the more anxious attachment, the greater their fear of losing their ideal partner. In a way, these studies are coherent, considering that one of the possible factors of this dependency is the traumatic bonding and the level of commitment these women have regarding their relationships.

A study by Christman (2009) noted that traumatic bonding mediates the relation between attachment and the intention to return to the abuser. The victims also forgive more easily for the purpose of remaining in the relationship. More exclusive dependency is demonstrated in relationships in which women have been engaged for more than 4 years and where there has already been a traumatic bonding, and/or where they have already been left by their partners (Petruccelli et al., 2014).

Our study also showed that women who were living with their partner during the isolation period had more exclusive dependency on their partner. That is, the more time women spend inside their homes, the more they become dependent on their partners. We obtained evidence that confirmed our hypothesis 4, showing that those women who are living with their partners may have higher levels of anxious attachment, being more afraid to stay away from their partners for fear of being abandoned. In addition, time of cohabitation showed significant differences in psychological abuse, such that women who live with their spouses full-time reported facing more psychological abuse.

In this regard, according to Bradbury-Jones and Isham (2020), the current COVID-19 pandemic presents itself as a unique and distressing paradox for women who are victims of violence in intimate relationships. They either stay at home with their partner at risk of further violence, or they leave home and risk being exposed to a highly infectious and dangerous virus. Coercive control is a hallmark of abusive relationships and according to studies, and, according to studies, abusers use the COVID-19 virus to instigate fear and obedience in their partners (Godin, 2020; Sandler, 2020), which is part of the repertoire of psychological abuse.

Despite the results, the present study is not without limitations. One of the limitations found is the lack of empirical studies that prove the hypotheses listed in this study, so that it can be compared cross-culturally. Most studies are about the theory itself (Amor & Echeburúa, 2010; Ramos, 2005) and do not focus on predictive or experimental models. One of the suggestions for further studies would be to explore more research to expand this theoretical framework, which should address social factors. Another limitation refers to the sampling characteristics, since it is non-probabilistic (by convenience), and a large part of the sample is composed of women with higher education, therefore, considering the generalization of the results for the entire population of women. A minority of 6.3% reported suffering psychological abuse or other types of abuse (physical, sexual, patrimonial). It is recommended that future studies reach participants of specific samples - such as women who are suffering psychological abuse concomitant with other types of abuse - that aim to relate the recurrence of the various forms of violence to emotional dependency and self-esteem.

Conclusion

This study was important to test a psychological process of the relation between psychological abuse, self-esteem, and emotional dependency, under the domain of the Theory of Traumatic Bonding (Dutton & Painter, 1981). That said, we comprehend that the present study is necessary and relevant, especially in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic. That said, it is understood that the present study is necessary and relevant, especially in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which, in turn, hinder escape routes, search for help, and ways of coping. In addition, we hope this study contributes to psychotherapeutic processes by applying motivational interviews and self-management of emotions to victims of violence (Sussman, 2010). We also hope this study contributes to the proposition of educational policies regarding the impact of violence on self-esteem - consequently on dependency -, as well as on how dependency plays a role in maintaining and accepting violence against women. By using scientific approaches (Bowlby, 1969; Dutton & Painter, 1993; Dutton & White, 2012; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959; Walker, 1979), our study demonstrated how psychological mechanisms can act on the acceptance of psychological abuse as well as on the acceptance of emotional dependency. Such approaches helped to identify the mechanisms of personal factors that underlie the risk of lethality of psychological abuse against women.

REFERENCES

Aizpurua, E., Copp, J., Ricarte, J. J., & Vázquez, D. (2021). Controlling behaviors and intimate partner violence among women in Spain: an examination of individual, partner and relationship risk factors for physical and psychological abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1-2), 231-254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517723744 [ Links ]

Amor, P. J. & Echeburúa, E. (2010). Claves Psicosociales para la Permanencia de la Víctima en una Relación de Maltrato. Clínica Contemporánea, 1(2), 97-104. https://doi.org/10.5093/cc2010v1n2a3 [ Links ]

Bigizadeh, S., Sharifi, N., Javadpour, S., Poornowrooz, N., Jahromy, F. H., & Jamali, S. (2021). Attitude toward violence and its relationship with self-esteem and self-efficacy among Iranian women. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 59(4) 31-37. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20201203-06 [ Links ]

Bornstein, R. F. (2006). The complex relationship between dependency and domestic violence: Converging psychological factors and social forces. American Psychologist, 61(6), 595-606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.595 [ Links ]

Boserup, B., McKenney, M., & Elkbuli, A. (2020). Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(12), 2753-2755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077 [ Links ]

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment. Basic Books. [ Links ]

Bradbury-Jones, C. & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: the consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13-14), 2047-2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15296 [ Links ]

Bution, D. C. & Wechsler, A. M. (2016). Dependência emocional: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia, Londrina, 6(1), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.5433/2236-6407.2016v7n1p77 [ Links ]

Christman, J. A. (2009). Expanding the theory of traumatic bonding as it relates to forgiveness, romantic attachment, and intention to return (Tese de mestrado, University of Tennessee). https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/30 [ Links ]

Costa, E. C. V. & Gomes, S. C. (2018). Social support and self-esteem moderate the relation between intimate partner violence and depression and anxiety symptoms among Portuguese women. Journal of Family Violence, 33, 355-368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-9962-7 [ Links ]

De Young, M. & Lowry, J. A. (1992). Traumatic bonding: clinical implications in incest. Child Welfare, 71(2), 165-175. [ Links ]

Drigotas, S. M. & Rusbult, C. E. (1992). Should I stay or should I go? A dependence model of breakups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 62-87. [ Links ]

Dutton, D. G. & Painter, S. L. (1981). Traumatic bonding: the development of emotional attachments in battered women and other relationships of intermittent abuse. Victimology: An International Journal, 6(January 1981), 139-155. [ Links ]

Dutton, D. G. & Painter, S. L. (1993). Emotional attachments in abusive relationships: a test of traumatic bonding theory. Violence and Victims, 8(2), 105-120. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.8.2.105 [ Links ]

Dutton, D. G. & White, K. R. (2012). Attachment insecurity and intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 475-481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.003 [ Links ]

Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública. (2020). Violência doméstica durante pandemia de Covid-19 (3ª ed.). http://forumseguranca.org.br/publicacoes_posts/violencia-domestica-durante-pandemia-de-covid-19 [ Links ]

Ghasemi, A. & Zahediasl, S. (2012). Normality Tests for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 10(2), 486-489. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.3505 [ Links ]

Godin, M. (2020, março 18). How coronavirus is affecting victims of domestic violence. Time. https://time.com/5803887/coronavirus-domestic-violence-victims/ [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [ Links ]

Kim, H. & Kahng, S. K. (2011). Examining the relationship between domestic violence and depression among Koreans: the role of self-esteem and social support as mediators. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 5(3), 181-197. https://doi.org/10.111/j.1753-1411.2011.00057.x [ Links ]

Moral, M. de la V. & Ruiz, C. S. (2009). Dependencia afectiva y género: Perfil sintomático diferencial en dependientes afectivos españoles. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 230-240. [ Links ]

Moral, M. de la V., García, A., & Ruiz, C. S. (2017). Violencia en el noviazgo, dependencia emocional y autoestima en adolescentes y jóvenes españoles. Revista Iberoamericana de psicología y salud, 8(2), 96-107. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2017.08.009 [ Links ]

Paiva, T. T., Cavalcanti, J. G., & Lima, K. S. (2020). Propriedades psicométricas de uma medida de abuso psicológico na Parceira. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 29, 45-59. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v29n1.72599 [ Links ]

Paiva, T. T., Cavalcanti, J. G., Lima, K. L., & Santos, I. L. S. (2021). Propriedades psicométricas da escala de dependência específica do cônjuge para mulheres (EDEC-M). CES Psicología, 14(3), 34-56. https://doi.org/10.21615/cesp.5417 [ Links ]

Paiva, T. T., Pimentel, C. E., & Moura, G. B. (2017). Violência conjugal e suas relações com autoestima, personalidade e satisfação com a vida. Gerais: Revista Interinstitucional de Psicologia, 10(2), 215-227. [ Links ]

Petruccelli, F., Diotaiuti, P., Verrastro, V., Petruccelli, I., Federico, R., Martinotti, G., Fossati, A., Di Giannantonio, M., & Janiri, L. (2014). Affective dependence and aggression: An exploratory study. BioMed Research International, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/805469 [ Links ]

Pimentel, C. E., Silva, F. M. de S. M. da, Santos, J. L. F. dos, Oliveira, K. G., Freitas, N. B. C., Couto, R. N., & Brito, T. R. de S. (2018). Escala de autoestima de item único: adaptação brasileira e relação com personalidade e comportamento pró-social. Psico-USF, 23(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712018230101 [ Links ]

Porrúa-García, C., Rodriguez-Carballeira, A., Escartin, J., Gomez-Benito, J., Almendros, C., & Martin-Pena, J. (2016). Development and validation of the scale of psychological abuse in intimate partner violence (Eapa-p). Psicothema, 28, 214-221. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2015.197 [ Links ]

Ramos, A. V. (2005). Agresión a la mujer como factor de riesgo múltiple de depresión. Psicopatología Clínica Legal y Forense, 5(1), 75-86. [ Links ]

Rathus, J. H. & O’Leary, K. D. (1997). Spouse-specific dependency scale: Scale development. Journal of Family Violence, 12(2), 159-168. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022884627567 [ Links ]

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151-161. [ Links ]

Rodriguez-Carballeira, A., Porrua-Garcia, C., Escartin, J., Martin-Pena, J., & Almendros, C. (2014). Taxonomy and hierarchy of psychological abuse strategies in intimate partner relationships. Anales de Psicología, 30, 916-926. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.154001 [ Links ]

Sandler, R. (2020, abril 7). Domestic violence hotline reports surge in coronavirus-related calls as shelter-in-place leads to isolation, abuse. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rachelsandler/2020/04/06/domestic-violence-hotline-reports-surge-in-coronavirus-related-calls-as-shelter-in-place-leads-to-isolation-abuse/#ea2d607793ab [ Links ]

Sbicigo, J. B., Bandeira, D. R., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2010). Escala de autoestima de rosenberg (EAR): validade fatorial e consistência interna. Revista Psico-USF , 15(3), 395-403. [ Links ]

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. B., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379-386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068 [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: on depression, development and death. Freeman. [ Links ]

Sussman, S. (2010). Love addiction: definition, etiology, treatment. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(1), 31-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/107220161003604095 [ Links ]

Tan, K., Arriaga, X. B., & Agnew, C. R. (2018). Running on empty: measuring psychological dependence in close relationships lacking satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(7), 977-998. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517702010 [ Links ]

Thibaut, J. W. & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. Wiley. [ Links ]

UN Women. (2020). COVID-19 and ending violence against women and girls. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls [ Links ]

Urbiola, I., Estévez, A., Iruarrizaga, I., & Jauregui, P. (2017). Dependencia emocional en jóvenes: Relación con la sintomatología ansiosa y depresiva, autoestima y diferencias de género. Ansiedad y Estres, 23(1), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2016.11.003 [ Links ]

Walker, L. E. (1979). The battered woman. Harper and Row. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2018). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women [ Links ]

How to cite: Paiva, T. T., Lima, K. da S., & Cavalcanti, J. G. (2022). Psychological abuse, self-esteem and emotional dependence of women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2257. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2257

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. T. T. P. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; K. da S. L. in a, b, c, d, e; J. G. C. in a, b, c, e.

Received: September 01, 2020; Accepted: September 30, 2022

texto en

texto en