Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.16 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2225

Original Articles

Analysis of the assumptions of the psychosocial paradigm in Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS) in the professional’s perspective

1 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil, guilherme.ferreiraa@gmail.com

2 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil

3 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil

The psychosocial care model was built with the development of a new mental health policy structure. As purpose, there is the guarantee of human dignity and the right to citizenship through devices that replace the asylum model. The objective of this article is to analyze, from the perspective of professionals, what they consider to be assumptions in this model and how they are operationalized in the daily life of Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS). It is a qualitative, transversal and exploratory study. It was done in Porto Alegre (Brazil) in 2019, with eleven professionals from different areas. Semi-directed interviews were conducted and for the analysis of data, thematic analysis was used. The results were organized into the most listed and elaborated assumptions by the participants: Autonomy, Territory, Citizenship, and Social Reinsertion. Different meanings attributed to the assumptions stand out, and their manifestations in care actions were consistent with the psychosocial paradigm.

Keywords: mental health; public policy; psychosocial care model; human rights; Brazil

O modelo de atenção psicossocial foi construído com a elaboração de uma nova estrutura de política de saúde mental. Como propósito, tem-se a garantia da dignidade humana e o direito à cidadania por meio de dispositivos que substituam o modelo asilar. O objetivo deste artigo é analisar, a partir da perspectiva de profissionais, o que consideram como pressupostos neste modelo e como se operacionalizam no cotidiano dos Centros de Atenção Psicossocial (CAPS). Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo, transversal e de caráter exploratório. Foi realizado em Porto Alegre (Brasil) em 2019, com onze profissionais de diferentes áreas. Foram conduzidas entrevistas semidirigidas e utilizou-se a Análise Temática para análise de dados. Os resultados foram organizados com os pressupostos mais elencados e elaborados pelos participantes: Autonomia, Território, Cidadania e Reinserção Social. Destaca-se diferentes sentidos atribuídos aos pressupostos, e suas manifestações em ações de cuidado coerentes com o paradigma psicossocial.

Palavras-chave: saúde mental; política pública; modelo de atenção psicossocial; direitos humanos; Brasil

El modelo de atención psicosocial se construyó con la elaboración de una nueva estructura de políticas de salud mental. Como propósito, existe la garantía de la dignidad humana y el derecho a la ciudadanía a través de dispositivos que reemplazan el modelo de asilo. El objetivo de este artículo es analizar, desde la perspectiva de los profesionales, lo que consideran supuestos de dicho modelo y cómo se operacionalizan en el cotidiano de los Centros de Atención Psicosocial (CAPS). Es un estudio cualitativo, transversal y exploratorio. Fue realizado en Porto Alegre (Brasil) en 2019, con once profesionales de diferentes áreas. Se realizaron entrevistas semidireccionadas y se utilizó el análisis temático para el análisis de datos. Los resultados se organizaron con los supuestos más enumerados y elaborados por los participantes: autonomía, territorio, ciudadanía y reinserción social. Se destacan diferentes significados atribuidos a los supuestos, y sus manifestaciones en las acciones de atención compatibles con el paradigma psicosocial.

Palabras clave: salud mental; política pública; modelo de atención psicosocial; derechos humanos; Brasil

In the field of mental health in Brazil, the hospital-centered model was predominant until the mid-1970s, based on psychiatric knowledge and with the purpose of isolating the population attended. This form of assistance generated many debates that questioned institutional violence, conceptions of madness and the entire asylum structure (Amarante, 2007; Brazil, 2005). In this context, the Brazilian Psychiatric Reform Movement was created, described as an ethical-political and social process (Brazil, 2005).

Simultaneously with the Psychiatric Reform Movement, the Brazilian Health Reform have brought as one of its foundations a wide definition of health, in which the disease is not the main reference. When it comes to the field of mental health, reformist movements sought to consider conceptions that did not take pathology from a medical/psychiatric point of view as a fundamental guideline. From the perspective of Psychosocial Care, this enabled new understandings of health processes (Amarante & Nunes, 2018).

Based on the achievements of the Psychiatric and Sanitary Reforms, the reformulation of mental health policies was elaborated, with the congregation of a set of substitute practices for the asylum model, called psychosocial care. This concept follows the many transformations of the asylum paradigm, such as the guarantee of human dignity and the construction of other care devices (Costa-Rosa et al., 2003).

According to Amarante (2007), the changes in the field of psychosocial care have four dimensions: theoretical-conceptual, with the deconstruction of reductionist theories and practices in psychiatry; technical-assistance, with the new services as care devices; sociocultural, with social reflection on madness, and juridical-political, with the review of legislation and obstacles to the exercise of citizenship. The changes in the individual dimensions, which take place simultaneously and are intertwined, form the complex social process in which the introduction of this model of care is located.

In the technical assistance field, the Psychosocial Care Center (CAPS) is the main substitute for psychiatric hospitals. It is an open, community health service with intensive care that aims to serve the population enrolled in its service area. It offers clinical follow-ups, stimulate the social reintegration of users through access to work, leisure, exercise of civil rights, and reinvigorate family and community ties (Brazil, 2004). It is worth mentioning that the CAPS is the central service of the Psychosocial Care Network, so it is not the only substitute for psychiatric hospitals, but part of an articulated network of different services that have as one of the objectives the integrality of care (Brazil, 2011).

It was from the publication of resolution 336 that the constitution and functioning of CAPS was regulated at the national level (Brazil, 2002). Despite the short history of CAPS, the need to develop evaluations has become essential not only for overcoming traditional asylum models, but also for the control and participation of civil society. One article points out that users and family members express a high level of satisfaction with CAPS (Kantorski et al., 2009). In a study on the effectiveness of CAPS, a reduction in crises among users and in hospital admissions for users of the intensive modality was observed (Tomasi et al., 2010).

Regarding the evaluation of services, in the scenario of consolidation of the psychosocial care model, it is considered essential to monitor how the components and objectives of current policies appear in the daily routine of services (Trapé & Onocko, 2017). In the research of Kantorski et al. (2009), the Psychosocial Care was analyzed and led to the strengthening of the autonomy of the users, the reduction of crises, the adherence to the service and the improvement of the socialization and organization of the users' lives.

In a study by Mello and Furegato (2008), it was analyzed how participants perceived CAPS through the psychosocial model. The number of hospitalizations, the freedom of users, the political role of the service and citizenship were listed. In turn, in a study by Silva et al. (2015), the psychosocial care was understood as a form of interdisciplinary and intersectoral treatment that aims to work with the user to develop their autonomy, reintegration, and social support.

With that being said, for the implementation of the policy to be in accordance with the psychosocial paradigm, it is essential that the treatment of subjects in psychological distress be carried out in their living area. Therefore, the intention is to develop users' autonomy and citizenship, with care that presupposes qualifying their experiences in the community through social reintegration (Ferreira & Bezerra, 2017). This description is aligned with what is recommended in Resolution 3088: the respect for human rights and the guarantee of autonomy; the diversification of care strategies; carrying out activities in the area with the intention of exercising citizenship and developing intersectoral actions that guarantee comprehensive care (Brazil, 2011).

Nowadays, there are discussions about the factors that weaken the efficacy of the psychosocial model. Some of them are: the coexistence of psychosocial and asylum paradigms in CAPS (Scaparo et al., 2013); the barriers encountered (biomedical bias, disease centrality, underfunding; Goulart, 2013), and the reinsertion of the psychiatric hospital into the care network (Pitta & Guljor, 2019).

In this context, it is important to reflect on how the foundations of the psychosocial model, observed in the literature and ministerial documents, are understood by professionals and how they unfold in care practices. The aim of this article is therefore to analyze, from the point of view of professionals, what they consider to be the premises of the psychosocial care model and how they are implemented in the daily life of CAPS.

Method

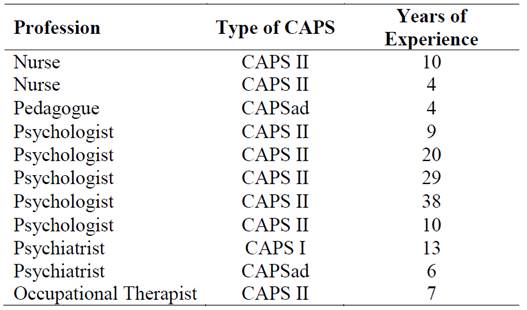

This study has a qualitative, cross-sectional and exploratory design. The research was held in 2019 in the city of Porto Alegre. Eleven professionals participated in the study: five psychologists, two psychiatrists, two nurses, a pedagogue and an occupational therapist, as shown in table 1. The participants were chosen for convenience. The inclusion criteria were: having experience of at least 4 years in CAPS and having knowledge about the psychiatric reform and the psychosocial care model. Only one professional did not accept to participate in the research due to lack of available time.

The contact with the participants happened via email. For data collection, semi-structured interviews were carried out in places previously agreed with the participants, from January to May 2019. The issues addressed referred to the premises of the psychiatric reform and the psychosocial care model; how these concepts were understood; how they were operationalized in care strategies, in addition to which were the barriers that made it difficult to implement. The interviews lasted approximately one hour, and were fully recorded and transcribed. To preserve the identity of the interviewees, the lines are identified as P1, P2, P3 and so on.

The data analysis was carried out from the thematic analysis, according to Braun and Clarke (2006). For this process, Atlas.ti software was used, in which the relevant themes were coded and grouped into thematic families. The families were organized based on the premises of the psychosocial paradigm that the professionals consider essential for everyday practices at CAPS. This selection took into account the frequency of citations, conceptual scope, and ability to indicate the type of operationalization.

The present study is the result of a master's thesis and is part of a larger project entitled “(Re)creating possibilities in Mental Health Policy: the construction and validation of an instrument for evaluating CAPS”. The development of this work corresponded to the qualitative and exploratory part of this project.

Regarding ethical aspects, the interviewees read and signed the Free and Informed Consent Term. The research was submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, and the Secretaria Municipal de Saúde de Porto Alegre under CAAE number: 99709118.6.0000.5336, and reports number 2,949.849 and 2,978.412.

Results and discussion

The analysis of the results was organized into four thematic axes, which, according to the participants, represent some of the basic assumptions of psychosocial care. These are: Autonomy; Territory; Citizenship and Social (Re)Inclusion. It is proposed to discuss how professionals understand these concepts and how they are reflected in the practice of services. An attempt has been made to contribute to a more detailed discussion of each of the elements.

It is worth mentioning that other assumptions of psychosocial care were mentioned by the participants, such as intersectoriality, integrality and humanization of care. However, these were not widely mentioned and there was not enough content to carry out an in-depth discussion. That said, it is not intended to prioritize the relevance of these elements, but to reflect on which were most cited and elaborated.

Autonomy

Based on the analysis of the interviews, autonomy was identified as the most mentioned element. Eight professionals reported that autonomy is fundamental to the practices in the service. They believe that the care process should not be carried out for the users but built with them. They consider that the treatment must take into account the user's wishes by valuing their role and providing tools that promote self-care outside the service. Furthermore, they believe that the service should listen to users, and consider their participation in organizational decisions and care management.

From one perspective, autonomy is constituted in the process of co-construction between subjects and collectives. Thus, the individual becomes co-responsible for him/herself and for society in a dynamic way (Onocko & Campos, 2007). Two of the interviewees brought in content that is consistent with the above. Based on their experiences at CAPS, they refer to a care process that is carried out through the sharing of responsibilities, in which the users play an active role in their treatment and in the functioning of the service.

I consider it very important to work with the subject's autonomy -you are not doing something for them, you are doing something with them- and sometimes it is a difficulty, we in health are trained to be prescriptive in treatments (P4). The issue of care management comes from a project thought along with them, so that within their suffering, in their life, the user is the protagonist of this care. In the experiences that I have had the opportunity to direct, users participated in the team meeting, managing the entire process. It is not easy, especially because they have always been historically submitted and relegated to a place of zero participation (P6).

Both professions face the challenge of working on autonomy because of the prescriptive legacy of the traditional health care paradigm. As a result, the incentive to establish a more horizontal relationship in the treatment process becomes important. Therefore, it is necessary to understand autonomy as an essential relational network for care that allows strengthening the connection between users and professionals. The purpose of this logic is to break with the idea of absolute autonomy (Romanini & Fernandes, 2018). The user's transition from a passive place in the treatment to an active position represents the power of the construction of care. In this mode of action, autonomy is understood as something interrelational and not individual static.

Still, in this aspect, a strategy mentioned to promote and foster autonomy -through the relationships between professional and user- is through Autonomous Medication Management (GAM). This strategy enables the user to have a significant position in treatment decisions, as can be seen in the following example:

The GAM, from autonomous medication management. I see users managing to fully discuss their treatment, being able to give their opinion, and say how much they will or will not use, what resources they want in their care (P6).

This experience is important for strengthening the autonomy of care. Implementing the GAM guide will solidify user participation in treatment management. To be effective, co-responsibility and protagonism in decisions related to the use of medications must be indispensable. In addition, there is a strengthening of criticality regarding care and psychotropic drugs themselves and their adverse effects (Cougo & Azambuja, 2018; Freitas et al., 2016). The GAM is an example of health care in which the user can be the protagonist of this process.

As for the process of autonomy beyond the treatment space, a professional mentions how this is effected in the personal life of a user. This achievement is pointed out as a result of the articulation that takes place in the contact with service professionals:

It is small day-to-day actions that we can articulate the process of autonomy. There is this user who was a very difficult person, very depressing, just tough, tough, tough, and today she manages to go to the market and say “Oh, I'm going to get some milk, give it to me and see if my payment has come in”. So, they do not have a prescription (P1).

It is clear, however, that the construction of autonomy depends on the scope and quality of the relationships that constitute the routine, and not only on individual capabilities. Thus, the essence of autonomy lies not in self-sufficiency, but in the interdependence of relationships. The strategy found by the user shows how autonomy is developed through relational interaction. To the extent that market collaborators understand and embrace this requirement, "autonomous activity" takes place through a collaborative relationship.

From another perspective, autonomy regarding mental health is more connected to independence and self-government. For this to occur, it is necessary to establish norms and relationships in the organization of daily life. In convergence, a professional reports that autonomy should:

Valuing the role of the user, for these simple everyday decisions, “how am I going to take care of myself beyond the CAPS doors?” So, to think that they have the direction of their lives in their hands, but to be able to give them the tools so that they can manage themselves, take care of themselves (P11).

The speech points out the importance of working on strategies that enable users to manage and improve their self-care outside the service. Thus, the realization of the construction of autonomy goes through the elaboration of a mediated autonomy. This mediation aims to advise the subjects to develop their own story and expand their network of relationships, without taking away the power of control over their own life (Dutra et al., 2017).

Based on the participants' narratives, it appears that despite the different conceptions, there is a consensus that autonomy should be stimulated and built together. Therefore, the objective is for the users to be the protagonist of their care and to qualify the networks of relationships that cause a greater inscription of their autonomous role in the collective. In different speeches, it was discussed how this concept is applied in daily life, which confirms an ability to put this principle into practice in the care process. On the other hand, the prescriptive history of health treatment was identified as barriers.

It is added that autonomy is directly linked to other assumptions. It is oriented to the investment in the subjects to expand their support network and make decisions as citizens. Their construction must be linked to the territory, insofar as practices committed to citizenship are promoted (Dutra et al., 2017).

Territory

Regarding the territory, six professionals point out that the concept goes beyond the understanding of physical territory as a geographical space, but rather represents a subjective process of feeling a sense of belonging, of getting to know people and places, which enables encounters and relationships in the community. Moreover, they believe that CAPS cannot only work in their space, but must articulate with the territory by accessing other devices, proposing activities outside the service and accompanying users in their daily lives.

CAPS must be contextualized in the user's social spaces (school, family, work, etc.), which means that the service must be territorialized. Its objective is to know the resources of the territory and their potential to use them in mental health care. Social reintegration needs to be stimulated from the service, but always focused on the community (Brazil, 2004). Regarding the development of territorial networks, from an international perspective, the Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 identifies as one of its objectives the development of mental health and social support services in a community context that can be networked and are able to meet demand (World Health Organization, 2013).

A systematic review of concepts of territory in mental health revealed four main meanings: territory as an area covered by community-based services; as a network of therapeutic resources that professionals must connect to other spaces; as a scenario of symbolic records and belonging based on each individual's personal history, and finally, as an interface between the political and the cultural with a material and social basis (Furtado et al., 2016).

According to two participants, the territory consists of interactions carried out by professionals between health services and community spaces. It is noticeable that their narratives provide a conceptual understanding of the term and how it should be put into practice, however, it is not described how this actually occurs in their experiences:

Mainly offering community-based assistance. The service cannot just be working within it. I see CAPS’ work as several hands in the territory, creating this networking interface. So, in my opinion, CAPS is much territory, actually (P4). The point is that you need to launch yourself into the territory, you cannot just settle within CAPS, but we also have to challenge ourselves to go beyond CAPS, to seek, to go after it (P8).

Free treatment should decentralize CAPS care and expand to the territory, with networks, intersectoral and community articulations (Brazil, 2015; Furtado et al., 2017). In the same direction, another participant affirms that territorial practices should transpose CAPS’ internal space. She reports how this principle was implemented in her daily practices. However, the unfolding of these meetings is missing, with an exposition of how the entry into the community occurred.

In the sense of providing activities in the context of the territory. I have worked at CAPS, we used to do many workshops in different spaces, some were held in community spaces, like clubs, schools (P8).

The role of professionals can be seen as intermediaries between users, family members and the community that enable interactions in the territory. In this way, the professional proposes mediations that support the user to find territorial resources and develop new ways of living (Dutra & Oliveira, 2015). It is worth noting that the logic of care in freedom may be more powerful when it is established in the service's strategies. In this way, it will not depend on the individual care conceptions of each professional.

In another example, an important aspect is the interaction of users in a meeting space for different people from the neighborhood. It is reported that they are invited to events, which allows a sense of belonging due to this integration:

Territory is subjective, not just physical; it's also a feeling of belonging. It is a process of getting to know the neighborhood association, for example, that throw parties and invite them, so there is a relationship that goes beyond the geographic territory (P1).

This understanding of territory can be understood from the point of view of social psychology, as the subjective dimension of social reality is highlighted, and it is emphasized that the way of interpreting the context is elaborated in the interaction. Thus, social practices form not only the social reality, but also the development of people and collectives in everyday life. The interviewee considers the territory as a subjective space and mentions that through these exchanges and encounters a sense of belonging is made possible.

Thus, the territory consists of relational arrangements, such as interpersonal, interinstitutional, and intersectoral arrangements. Therefore, not only the health units should participate in the care network, but also the different components of the network that participate in a cooperative relationship in the construction of the collective well-being (Alves & Silveira, 2011; Martins et al., 2015).

Regarding the statements, it is noted that the practices in the territory are very limited to a management dimension of health services with other sectors (Ferreira et al., 2016). That is, the possible forces of resistance - from the clinical, economic or moral sectors - are not mentioned in the face of social reintegration movements (Furtado et al., 2016). Considering the territory as a place occupied by these subjects in a limited way, one cannot ignore the possibility of resistance from different directions in this insertion process.

To overcome obstacles, the effectiveness and goal of territoriality must be invested in conjunction with other assumptions. For example, the potential for interaction in the territory is associated with greater autonomy for users. Based on the mediation of professionals, users must be socially empowered to take advantage of the resources of the territory (Dutra & Oliveira, 2015).

Therefore, it is noted that the concept of territory focuses on the different articulations in the care process, such as the network and spaces of coexistence. These meanings are consistent with what is proposed in psychosocial care and advocated in current mental health policy. Although some participants point to how the practice of territoriality plays out, the lack of description of these actions in everyday life may be a symptom of the difficulty in translating this assumption into concrete care strategies.

Citizenship

Citizenship was considered an essential element for the daily life of CAPS by seven professionals. The participants brought up that this assumption is related to the guarantee of rights, such as access to culture, education and work. It was mentioned that the services aim to rescue this role of citizen, whether from paid work (or not), but that can produce something in society.

Citizenship represents the relationship of political society with its members. In this sense, exercising citizenship means acting for the benefit of society, which must guarantee the basic rights to life, such as housing, food, health, education and work (Gorczevski & Belloso, 2011).

With the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, the system began to guarantee universal access to measures to promote, protect and restore health. With the changes in the mental health care model and the demand for the rights of people in psychological distress, a paradigm shift was made in this area, consisting in the position of subjects of rights (Ferreira & Bezerra, 2017).

However, this fight cannot be limited only to legislative approvals, because it is not by decree that people are constituted as citizens. It is necessary to change conceptions, behaviors and social exchanges to effect the construction of citizenship, which is characterized as a complex social process (Amarante, 2007).

The question of rescuing the role of citizen of the subject, I think, also enters into the question of the objectives of enabling this search, the rescue of that person's citizenship (P8).

The care in the daily life of CAPS needs to be supported by historical and political knowledge, so that the treatment is not limited to intrapsychic issues. That is, professionals must also carry out a practice aimed at elucidating access to conquered rights. One participant mentions how this action could happen:

Citizenship groups exist because it is very important for people to exercise their citizenship, to see about their rights, how they can guarantee those that belong to them (P4).

The opening of space for dialogue on users' rights is powerful for a greater reach of information and greater access to benefits guaranteed by law. A significant achievement -in the country's redemocratization process- was the Continued Monthly Benefit (BPC), as highlighted by a professional:

With the support of BPC, users started to have an income. The users, who took the place of the rejected patient because they were a financial burden, became the breadwinner of the family (P6).

The professional highlights that the BPC is a right that can promote a change of position in the family organization. This benefit -along with other forms of support- helps not only in the emancipation of the user within the family, but also in society, as their rights as citizens are assured. The BPC qualifies as the guarantee of basic income in the sphere of state social protection (Stopa, 2019).

In view of the above, it is worth emphasizing the importance of the spaces in CAPS for the discussion of aspects such as users' rights and obligations. On the other hand, this static work affects the practice of citizen participation, which is addressed to different sectors of society:

We have produced a user dependency in CAPS and the production of life beyond disease is not happening in culture, education, and work. If CAPS and the network do not make these connections with the city, citizenship cannot be fostered (P6).

According to this professional, it is important that the production of life and citizenship be stimulated by CAPS. The service cannot create a restricted relationship with the user, but articulate connections with the city. In order to stimulate the production of citizenship that goes beyond the CAPS space, the different instances of the subject's life must be taken into account:

Instead of bringing these projects to the services, we looked for them in the city, we did theater, paper recycling and school at EJA (Education for Youth and Adults). Anything that contributes to involvement in the city. We went out to listen to music, for example, there was a user who used to sing a lot, and our job was to go to karaoke places for her to sing. I think that the city pulsates, produces, interferes and leaves the logic that your life is the disease (P4).

The expanded care for the different scenarios of the city produces citizenship and increases the circulation network of users. The speech of this participant demonstrates that this happens in two ways. One in support of functional attributions -such as in education and work- and the other in immersion in cultural spaces, which produce quality of life and increased well-being. Thus, the treatment considers the integrality of the subject and is no longer focused on the cure, but on the exercise of citizenship (Santiago & Yasui, 2020).

It is worth mentioning that, despite the professionals bringing important components of citizenship, some significant democratic spaces were not mentioned, such as assemblies and health councils. These environments represent the right of users to actively participate in daily decisions of the services and in the instances of social control.

Given what has been discussed about citizenship, it seems to be a fundamental assumption for care in CAPS. Saving citizenship is highlighted as one of the main goals of mental health policy. However, the professionals restricted these practices to groups regarding access to rights and benefits, and movement in the city. Although related to the process of citizenship, these pathways seem to belong more to the field of social reintegration, as will be seen in the next focus.

It is questioned whether some processes that were not mentioned, would no longer be associated with citizenship, such as the fight of social movements, the elaboration of policies that recognize the rights of users, and scenarios of representative participation. Thus, due to the lack of a more specific conceptualization of each term and the intertwining of the two assumptions, inaccuracies of what belongs to each field are presented. As possible obstacles to its implementation, the restriction of care in CAPS and the lack of intersectoral articulation and with the city were mentioned.

Social (Re)insertion

Regarding social reintegration, seven participants mentioned its importance in the care process. According to the professionals, social inclusion takes place through an opening to the community, through socialization activities and a daily life in different spaces, such as clubs and schools. It refers to the areas of culture, education, leisure and work through income-generating workshops or formal employment.

Social reintegration can therefore be understood as the establishment and/or restoration of impaired social interactions. It is a lengthy, gradual and dynamic process, as it involves the deconstruction of stigma and the creation of citizenship rights. Ultimately, it aims to enable those affected to exercise their rights and responsibilities (Observatório de Informações Sobre Drogas, 2007).

The implementation scenario of CAPS states that one of the main objectives is social reintegration. This movement aims to enable coexistence with their families, peers, and other parts of society, as well as occupation of different social spaces through strengthening citizenship rights (Passos & Aires, 2013). According to one professional, this can be achieved through strategies that provide some form of work, either through partnerships with businesses or through income-generating workshops:

May they be rescuing this role, having their own workspace, like the income generation workshops. Some users, even if accompanied at CAPS, also have their work a few hours a day, there are some places that work with social inclusion, but that is still very little (P8).

So, social inclusion is a theoretical framework that we use. Today, through quotas in formal companies, there is the Young Apprentice. We discuss with SENAC (National Service for Commercial Learning) many training courses, so that we are not just a forwarder of users, but that we are followers (P5).

Participation in the labor market - through inclusive policies - is a way to realize social inclusion in the current economic system in the face of some obstacles (such as prejudice and stigmatization). An example of this is the solidarity economy, which allows people to practice civic engagement in the social fabric through work experience, such as in workshops and income-generating projects (Santiago & Yasui, 2015).

In this way, attention is extended to cases that are not covered only by the treatment within CAPS, such as work performance. It is worth noting that the Singular Therapeutic Project is an important tool in which these issues can be developed with the user.

However, in addition to the labor sector, there are other areas that make up people's relational lives and provide social integration. An example of this is investment in the cultural sector:

There is an important issue that is social reintegration, in the sense of providing activities within the social context, through the participation in a few important regional events of the local culture. I think these are moments and spaces that we can be inserting these people (P8).

The scope of culture means harnessing socio-political knowledge and penetrating previously unoccupied contexts in order to achieve a better quality of life through the exercise of living together. These spaces create a science of local culture and allow a critique and/or an identification of regional beliefs and customs.

Activities articulated outside CAPS allow affective exchanges in other scenarios. These strategies motivate new places for people in psychological distress regarding the cultural and social field (Kammer et al., 2020). In view of this, seeking comprehensive care makes it possible to expand strategies, understand the subject's life through different prisms, and not only focus on their disease:

Putting the disease in parentheses, in which it is not the one in command, then there is the disease that has to be treated, but there is life, there is existence, education, work, housing, leisure (...) and we will work with these relationships to increase their contractuality with society (P10).

I think the risk is that CAPS captures the user again in the centrality of care, but also in the centrality of life. Our work was a lot on the street, in the family, with the network and for insertion at work (P6).

Both professionals emphasize that the logic of reintegration aims to decentralize the care of the user and the service in order to extend it to the different areas of life. The proposal to extend the contractuality of the user with the social life is a way to break with the old "exclusive" contract of the asylums. Consequently, it opens a series of scenarios, encounters and reciprocal experiences between subject and society.

The increase in social interaction of users is based on a variety of practices that crave their involvement. It is worth noting that these interventions require coherence with the user's culture and desires. Therefore, the reintegration of the user in the territory is not limited to the connection with sectors and services or the introduction to other spaces. The reintegration requires a construction from the subject's perspective (Ferreira & Bezerra, 2017).

From what has been said, it is identified that the interviewees develop care strategies aimed at social reintegration. These actions appeared as a movement not only in CAPS, but also in other spaces, and also with inclusion actions. The relevance of reinsertion practices lies in the investment in other areas of the subject's life, while working with the deconstruction of stigma and with other possibilities than just the disease. What does not seem to be clear, however, are the ideas that participants have about this concept in their presentations. This concept is often explained with examples of how it is carried out.

Conclusions

The psychosocial care model aimed to restructure mental health policy based on the review of exclusionary and discriminatory norms. On this basis, the system was built to ensure civil and human rights through care strategies that are both assumptions of the paradigm and everyday practices.

It is considered that it is not by chance that the assumptions discussed here were most memorable to the participants. The psychiatric reform brought as a great legacy the repositioning of the subject of madness in the position of citizen, with care in the territory, the development of autonomy and its reinsertion, its greatest banners. CAPS, as an important institution, conceived as an open and welcoming service, is one of the scenarios in which the practice of such elements is carried out.

Different perceptions and experiences have been noted in relation to these assumptions. Autonomy is seen as essential to the construction of care strategies. The plurality of perceptions of the concept and examples practiced underscores its importance in care practices. Actions in the field were mentioned several times, but it was not clear how they occur. Therefore, discussions about possible barriers or opportunities were not developed.

Citizenship was defined as one of the main objectives of the policy and is included in all its regulations. Neglecting important spaces can be a sign of lack of investment in them. Social reintegration was highlighted as a strategy to extend care to areas of life other than illness. The expansion of services aims at the integrality of care involving other sectors. Through the analysis of the different assumptions, their complementarity in daily life is identified. Regarding the difficulties in operationalization, care has been associated only with CAPS and insufficient articulation with the network and other spaces.

It is believed that this discussion is relevant to the review of the assumptions underlying the psychosocial paradigm. Analyzing the ways in which the principles are brought to bear in care strategies allows for an assessment of the limitations and potential of actions. As a result, opportunities open up for (de)construction, problematization, and solutions aimed at improving a field that is constantly changing and developing.

Finally, one of the limitations of this study is that only the interview was used as a data source, without including observations or a field diary. However, it should be noted that the results reflect the complexity of the theme of assumptions as theoretical-practical elements in the context of psychosocial care. Based on the identification of the intertwining of assumptions, it is suggested that future studies can analyze how this interconnection occurs. Transversalization of these principles may assist in the implementation and construction of new mental health care practices.

REFERENCES

Alves, C. C. F. & Silveira, R. P. (2011). Família e redes sociais no cuidado de pessoas com transtorno mental no acre: o contexto do território na desinstitucionalização. Revista de APS, 14(4), 454-463. [ Links ]

Amarante, P. & Nunes, M. O. (2018). A reforma psiquiátrica no SUS e a luta por uma sociedade sem manicômios. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 23(6), 2067-2074. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018236.07082018 [ Links ]

Amarante, P. (2007). Saúde mental e atenção psicossocial. Fiocruz. [ Links ]

Brasil. (2002). Portaria GM n° 336, de 19 de fevereiro de 2002. Ministério da Saúde. [ Links ]

Brasil. (2004). Saúde mental no SUS: os centros de atenção psicossocial. Ministério da Saúde. [ Links ]

Brasil. (2005). Reforma psiquiátrica e política de saúde mental no Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. [ Links ]

Brasil. (2011). Portaria n. 3.088, de 23 de dezembro de 2011. Ministério da Saúde. [ Links ]

Brasil. (2015). Centros de Atenção Psicossocial e Unidades de Acolhimento como lugares da atenção psicossocial nos territórios: orientações para elaboração de projetos de construção, reforma e ampliação de CAPS e de UA. Ministério da Saúde. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [ Links ]

Costa-Rosa, A., Luzio, C. A., & Yasui, S. (2003). Atenção Psicossocial: rumo a um novo paradigma na Saúde Mental Coletiva. Em P. Amarante (Org.), Archivos deSaúde mental e atenção psicossocial , (Vol. 2, pp. 13-44). Nau. [ Links ]

Cougo, V. R. & Azambuja, M. A. D. (2018). A Estratégia gestão autônoma da medicação e a inserção da (a)normalidade no discurso da cidadania. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 38(4), 622-635. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703001072017 [ Links ]

Dutra, V. F. D. & Oliveira, R. M. P. (2015). Revisão integrativa: as práticas territoriais de cuidado em saúde mental. Aquichan, 15(4), 529-540. http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2015.15.4.8 [ Links ]

Dutra, V. F. D., Bossato, H. R., & Oliveira, R. M. P. (2017). Mediar a autonomia: um cuidado essencial em saúde mental. Escola Anna Nery - revista de Enfermagem, 21(3), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2016-0284 [ Links ]

Ferreira, G. H. L. & Bezerra, B. D. G. (2017). A “reinserção” social dos usuários (as) dos CAPS II do município de Mossoró-RN sob a ótica das assistentes sociais. Revista Includere, 3(1), 51-62. [ Links ]

Ferreira, J. T., Mesquita, N. N. M., da Silva, T. A., da Silva, V. F., Lucas, W. J., & Batista, E. C. (2016). Os Centros de Atenção Psicossocial (CAPS): uma instituição de referência no atendimento à saúde mental. Revista Saberes, Rolim de Moura, 4(1), 72-86. [ Links ]

Freitas, A. C. M., Reckziegel, J. B., & Cássia Barcellos, R. (2016). Empoderamento e autonomia em saúde mental: o guia GAM como ferramenta de cuidado. Saúde (Santa Maria), 42(2), 149-156. [ Links ]

Furtado, J. P., Oda, W. Y., Borysow, I. D. C., & Kapp, S. (2016). A concepção de território na saúde mental. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 32(9), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00059116 [ Links ]

Furtado, R. P., Sousa, M. F. D., Martinez, J. F. N., Rabelo, N. S., Oliveira, N. S. R. D., & Simon, W. D. J. (2017). Desinstitucionalizar o cuidado e institucionalizar parcerias: desafios dos profissionais de Educação Física dos CAPS de Goiânia em intervenções no território. Saúde e Sociedade, 26(1), 183-195. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902017169101 [ Links ]

Gorczevski, C. & Belloso, N. (2011). A necessária revisão do conceito de Cidadania: movimentos sociais e novos protagonistas na esfera pública democrática. Edunisc. [ Links ]

Goulart, D. M. (2013). Autonomia, saúde mental e subjetividade no contexto assistencial brasileiro. Revista Científica Guillermo de Ockham, 11(1), 21-33. https://doi.org/10.21500/22563202.599 [ Links ]

Kammer, K. P., Moro, L. M., & Rocha, K. B. (2020). Concepções e práticas de autonomia em um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial (CAPS): desafios cotidianos. Revista Psicologia Política, 20(47), 36-50. [ Links ]

Kantorski, L. P., Jardim, V. M. R., Wetzel, C, Olschowsky, A., Schneider, J. F., Resmini, F., Heck, R. M., Bielemann, V. L M., Schwartz, E., Coimbra, V. C. C., Lange, C., & Sousa, A.S. (2009). Contribuições Do Estudo De Avaliação Dos Centros De Atenção Psicossocial Da Região Sul Do Brasil. Cad. Bras. Saúde Mental, 1(1), 1-9. [ Links ]

Martins, Á. K. L., Ferreira, W. D., Soares, R. K. O. & Oliveira, F. B. (2015). Práticas de equipes de saúde mental para a reinserção psicossocial de usuários. SANARE-Revista de Políticas Públicas, 14(2), 43-50. [ Links ]

Mello, R. & Furegato, A. R. F. (2008). Representações de usuários, familiares e profissionais acerca de um centro de atenção psicossocial. Escola Anna Nery - revista de Enfermagem , 12(3), 457-64. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-81452008000300010 [ Links ]

Observatório de Informações Sobre Drogas. (2007). Drogas. O que é a droga. Mundo jovem no OBID. [ Links ]

Onocko, R. T. C. & Campos, G. D. S. (2007). Co-construção de autonomia: o sujeito em questão. Em G. W. S. Campos, M. C. S. Minayo, M. Akerman, J. M. Drumond & Y. M. Carvalho (Orgs.), Tratado de saúde coletiva (pp. 669-688). Hucitec. [ Links ]

Organização Mundial da Saúde. (2013). Mental health action plan, 2013-2020. [ Links ]

Passos, F. P. & Aires, S. (2013). Reinserção social de portadores de sofrimento psíquico: o olhar de usuários de um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva, 23(1), 13-31. [ Links ]

Pitta, A. M. F. & Guljor, A. P. (2019). A violência da contrarreforma psiquiátrica no Brasil: um ataque à democracia em tempos de luta pelos direitos humanos e justiça social. Cadernos do CEAS: Revista crítica de humanidades, (246), 6-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.25247/2447-861X.2019.n246.p6-14 [ Links ]

Romanini, M. & Fernandes, V. M. (2018). Os processos de autonomia no cotidiano de um CAPS Ad III: (Re)pensando práticas, (Re)construindo caminhos. Diálogo, (39), 9-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.18316/dialogo.v0i39.4046 [ Links ]

Santiago, E. & Yasui, S. (2015). Saúde mental e economia solidária: cartografias do seu discurso político. Psicologia & Sociedade, 27(3), 700-711. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-03102015v27n3p700 [ Links ]

Santiago, E. & Yasui, S. (2020). O trabalho como estratégia de atenção em saúde mental: um estudo documental. Revista Psicologia e Saúde, 12(3), 109-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.20435/pssa.vi.1064 [ Links ]

Scaparo, H., Leite, L. S., & Santos, S. J. E. (2013). Saúde mental em Porto Alegre: considerações sobre os nossos caminhos. Em L. S. Leite, H. Scaparo, M. Dias & S. J. E. Santos (Orgs.), Saúde mental ConVida: Registros da Trajetória da Saúde Mental na Cidade de Porto Alegre (pp. 140-147). Secretaria Municipal de Saúde. [ Links ]

Silva, G. M., Zanini, D. S., Rabelo, I. V. M., & Pegoraro, R. F. (2015). Concepções sobre o modo de Atenção Psicossocial de profissionais da saúde mental de um CAPS. Revista Psicologia e Saúde , 7(2), 161-167. [ Links ]

Stopa, R. (2019). O direito constitucional ao Benefício de Prestação Continuada (BPC): o penoso caminho para o acesso. Serviço Social & Sociedade, (135), 231-248. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-6628.176 [ Links ]

Tomasi, E., Facchini, L. A., Piccini, R. X., Thumé, E., Silva, R. A., Gonçalves, H., & Silva, S. M. (2010). Efetividade dos Centros de Atenção Psicossocial no cuidado a 42 portadores de sofrimento psíquico em cidade de porte médio do Sul do Brasil: uma análise estratificada. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 26(4), 807-815. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2010000400022 [ Links ]

Trapé, T. L. & Onocko, R. T. C. (2017). Modelo de atenção à saúde mental do Brasil: análise do financiamento, governança e mecanismos de avaliação. Revista de Saúde Pública, 51, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1518-8787.2017051006059 [ Links ]

Financing: This study was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development), with a master's grant from author G. S. Ferreira and a research productivity grant from author K. B. Rocha.

How to cite: Severo Ferreira, G., Moraes Moro, L., & Bones Rocha, K. (2022). Analysis of the assumptions of the psychosocial paradigm in Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS) in the professional’s perspective. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2225. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2225

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. G. S. F. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; L. M. M. in a, c, d, e; and K. B. R. in a, c, d, e.

Received: July 21, 2020; Accepted: August 25, 2022

texto en

texto en