Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.16 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2767

Original Articles

Attitudes towards social policies: from individual indicators to latent constructs

1 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina, ceciliareyna@unc.edu.ar

2 Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina

3 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina

4 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina

The objective of this study was to identify latent dimensions of attitudes towards social policies from a series of items commonly used in locally relevant literature on the subject. Specifically, we analysed evidence of structural validity and internal consistency of a set of 24 items on attitudes towards social policies. A total of 442 people aged 18 to 64 from Gran Cordoba (Argentina) participated. Exploratory and confirmatory (two factors, three factors, four factors, second order) models were assessed. The exploratory evidence did not provide satisfactory results. In the confirmatory analyses, the four-factor model showed an acceptable fit, with the following item clustering: targeted beneficiary-centred policies that tend towards social welfare (7 items), targeted beneficiary-centred policies that tend toward social advancement (6 items), targeted contributor-centred policies (4 items), and universal policies (7 items). All items showed factor loadings greater than .40. The internal consistency values were higher than .70. The results showed the possibility of considering latent dimensions on attitudes towards social policies. We underline the need to develop interdisciplinary and contextualized research in this regard.

Keywords: social policies; attitudes; psychometric properties; reliability and validity

El objetivo de este estudio fue avanzar hacia la identificación de dimensiones latentes a partir de una serie de ítems comúnmente utilizados en la literatura sobre políticas sociales con relevancia local. Específicamente, se analizó la evidencia de validez estructural y de consistencia interna de un conjunto de 24 ítems sobre actitudes hacia políticas sociales. Participaron 442 personas de 18 a 64 años del Gran Córdoba (Argentina). Se evaluaron modelos de manera exploratoria y confirmatoria (dos factores, tres factores, cuatro factores, segundo orden). La evidencia exploratoria no arrojó resultados satisfactorios. En los análisis confirmatorios el modelo de cuatro factores mostró un ajuste aceptable, con el siguiente agrupamiento de ítems: políticas focalizadas centradas en el beneficiario que tienden a la asistencia (7 ítems), políticas focalizadas centradas en el beneficiario que tienden a la promoción (6 ítems), políticas focalizadas centradas en el contribuyente (4 ítems) y políticas universales (7 ítems). Todos los ítems mostraron cargas factoriales superiores a .40. Los valores de consistencia interna fueron superiores a .70. Los resultados evidencian la posibilidad de considerar dimensiones latentes a las actitudes hacia políticas sociales. Se destaca la necesidad de desarrollar trabajos interdisciplinarios y con anclaje local en relación a la temática.

Palabras clave: políticas sociales; actitudes; propiedades psicométricas; confiabilidad y validez

O objetivo deste estudo foi avançar na identificação de dimensões latentes a partir de uma série de itens comumente utilizados na literatura sobre políticas sociais com relevância local. Especificamente, analisamos as evidências de validade estrutural e consistência interna de um conjunto de 24 itens sobre atitudes em relação às políticas sociais. Participaram 442 pessoas de 18 a 64 anos da Grande Córdoba (Argentina). Os modelos foram avaliados de forma exploratória e confirmatória (dois fatores, três fatores, quatro fatores, segunda ordem). Os resultados da evidência exploratória foram insatisfatórios. Em análises confirmatórias, o modelo de quatro fatores mostrou um ajuste aceitável. Esse modelo implica o agrupamento dos itens nas seguintes dimensões: políticas direcionadas ao beneficiário que tendem a cuidar (7 itens), políticas direcionadas ao beneficiário que tendem a promover (6 itens), políticas direcionadas ao contribuinte (4 itens) e políticas universais (7 itens). Todos os itens apresentaram cargas fatoriais superiores a 0,40. Os valores de consistência interna foram maiores que 0,70. Os resultados mostram a possibilidade de considerar dimensões latentes nas atitudes em relação às políticas sociais. Destacamos a necessidade de desenvolver um trabalho interdisciplinar e ancorado localmente.

Palavras-chave: políticas sociais; atitudes; propriedades psicométricas; confiabilidade e validade

Social inequality is one of the most important problems facing contemporary societies. Latin America is one of the most unequal regions on the planet (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2018). This situation has been exacerbated by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in Argentina (ECLAC, 2020). Latin American governments have implemented different social policies to reduce inequality in the region (Duryea, 2016).

Finding an unequivocal definition of social policies is as complex as the problems they seek to solve. According to De Sena (2014), social policies have a direct impact on the conditions for the production and reproduction of people's lives, and desirable models of society underlie them. Herein lies the difficulty in its conceptualization. There is some consensus, however, on the method to determine eligibility for social policies. There are three main criteria: need (targeted tools or targeting, Filgueira, 2014; targeting model or social welfare policies, Home Arias, 2012; targeted social policies, Ochman, 2014), contribution (contributory models, Filgueira, 2014) and citizenship (universalism or universal policies, Danani, 2017; non-contributory universal models, Filgueira, 2014; universalism or universal policies, Home Arias, 2012).

In Argentina, different types of social policies coexist. The basis of social policies has historically been the Argentine pension system, which is related to the formal salaried employment, i.e., the contributory system. There are also universal public institutions of education and health as well as particular interventions aimed at people in vulnerable situations or those who meet specific criteria (e.g., conditional cash transfers) (Boga, 2018).

The focus of this paper is the analysis of attitudes toward universal and targeted social policies, both types have advantages and disadvantages. The debate on universalism versus targeting became relevant in the 1990s, some authors state that it was a result of the country's impoverishment and the spread of neoliberal ideas supporting the allocation of resources only to those who needed them the most, thus challenging the universal models (Danani, 2017; Home Arias, 2012).

Advocates of targeting argue that this type of policy is cost-effective, as it allows rationalizing public spending (Filgueira, 2014; Home Arias, 2012; Ochman, 2014). On the other hand, those who are against, argue that the high administrative costs generated by determining who is the deserving group of the social policy neutralize such fiscal efficiency and, in turn, such determination is often inaccurate, resulting in inclusion/exclusion errors (Garriga & Rosales, 2013; Home Arias, 2012; Ochman, 2014). In sum, defining the need is a difficult task, but demonstrating it also entails a cost, particularly for poor people who must overcome symbolic (e.g., lack of skills and abilities) and bureaucratic (e.g., paperwork, travel) barriers in order to be beneficiaries of a given policy (Ochman, 2014). Another argument against this is the stigmatization produced by being singled out as a recipient of a certain policy, which promotes processes of inequality and even fraudulent behaviour or clientelism (Filgueira, 2014; Garriga & Rosales, 2013; Home Arias, 2012).

On the other hand, universal social policies mitigate many of the disadvantages of targeted policies since they contribute to the consolidation of a sense of equality and citizen solidarity (Home Arias, 2012), promoting the goal of social cohesion (Filgueira, 2014). In turn, universalism makes middle-class people beneficiaries, which generates the necessary political support for their sustainability (Garriga & Rosales, 2013). However, although they circumvent the high administrative burdens of defining the recipient group, universalism is costly and requires a strong tax resource base (Filgueira, 2014; Home Arias, 2012).

From the psychological perspective, there is evidence that contributes to a better understanding of the support that social policies receive from citizens. For example, theoretical models have been developed on the role of altruism and its relationship with preferences for redistributive policies (Dimick et al., 2018), and the role of beliefs about inequality and their impact on support for redistributive policies (e.g., García-Sánchez et al., 2020) as well as on attitudes towards redistribution (e.g., García-Castro et al., 2022).

The study of people's attitudes towards social policies is fundamental if we consider that citizen support is essential to grant legitimacy to political action (Castillo & Olivos, 2014). Attitudes can be understood as people's assessments of a given object (Albarracín et al., 2005). In general, attitudes towards social policies have been studied as a one-dimensional construct and measured through one or a few items (e.g., International Social Survey Programme, General Social Survey, and World Values Survey). However, a recent study has investigated a structure composed by different dimensions (Cavaillé & Trump, 2015).

According to Steele and Breznau (2019), a single-item measurement of attitudes toward social policies is unreliable because it overlooks latent dimensions of redistributive policies. Along these lines, Cavaillé and Trump (2015) point out that attitudes towards redistributive policies are not one-dimensional and comprise two broad dimensions: 1) redistribution from, linked to income maximization (self-oriented) whereby individuals perceive themselves as potential beneficiaries of redistribution from rich people, so they could receive material gains, and 2) redistribution to, linked to social affinity (other-oriented) whereby individuals perceive themselves as potential contributors to redistribution to poor people and their motives are oriented to consider others (e.g., empathy for the recipients of redistribution). In summary, these authors consider that these attitudes are empirically distinct from one another.

It should be noted that, even when social policies have been characterized as targeted or universal, centred on the contributor or the beneficiary, it is possible to observe certain targeted social policies in Argentina that promote welfare (e.g., conditional cash transfers; Bráncoli, 2021) or social advancement, improving certain living conditions (e.g., the ProHuerta food safety program; Vinocur & Halperin 2004). In this line, Home Arias (2012) points out that in Argentina the model of intervention on poverty has been built on the basis of social welfare and social advancement policies. Social welfare policies are considered as short-term, palliative measures, often associated with the delivery of material resources (in kind or cash). On the other hand, social advancement policies are characterized by generating changes at the subjective level of the recipients and are associated with non-material aspects of poverty.

In order to measure the attitudes towards these social policies, this paper recovers a series of items commonly used in the field on social policies, locally relevant, as a first approximation towards the identification of latent dimensions of the construct of interest. Therefore, we analyse evidence of structural validity and internal consistency of a set of items on attitudes towards social policies in a sample of citizens of Gran Córdoba (Argentina). This approach would be complementary to the traditional one-dimensional measurement of attitudes towards social policies.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 442 people of different genders (female = 333, 75.3 %; male = 106, 24 %; other = 3, 0.7 %) aged 18-64 (M = 38.61, SD = 14.23) from Gran Córdoba (Argentina). The socioeconomic status of the individuals was marginal and lower low = 32, 7.2 %; higher low = 76, 17.2 %; lower middle = 131, 29.6 %; middle = 139, 31.4 %, higher middle and high = 64, 14.5 %.

Instruments

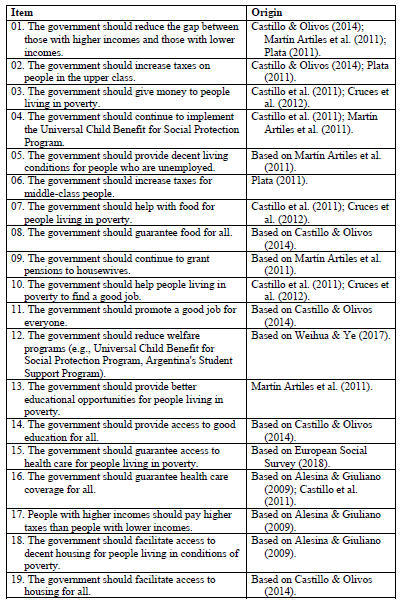

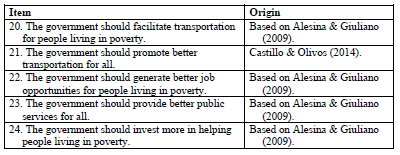

A set of 24 items addressing attitudes toward social policies employed in different previous studies (Alesina & Giuliano, 2009; Castillo & Olivos, 2014; Castillo et al., 2011; Cruces et al., 2013; ESS ERIC, 2018; Martín-Artiles et al., 2011; Plata, 2011; Weihua & Ye, 2017; see detail in Appendix A) was used. The items were tested among the team, particularly in terms of clarity and local relevance. The rating scale was unified. Specifically, a 5-point Likert-type response scale was used (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

In addition, socio-demographic information was collected. To calculate the socio-economic level, the following variables were taken into account: educational level, type of occupation, ratio between the number of contributors in the household and the number of inhabitants in the household, and health coverage (Comisión de Enlace Institucional (Argentine Institutional Liaison Commission), 2015).

Procedure

Data collection was performed within the framework of another study in which related variables not covered in this report were addressed. Participants were invited through social networks (Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp) and email. People responded to an online survey available on the LimeSurvey platform and were entered into a prize draw for cash prizes as a way of encouraging participation. The database, scripts, questionnaire, and appendix are available at <https://osf.io/5vhjd/?view_only=1b763e775dc0482eb72771541bd27bc5>.

Data analysis

In order to analyse the underlying structure, two strategies were employed: an exploratory one, to examine the latent constructs, and a confirmatory one, to evaluate the data fit to models defined from the literature. For this purpose, the sample was randomly divided into two halves (A and B). With each sample, descriptive statistics were calculated for the different items. Factor structure analyses were conducted with sample A (n = 221). The sedimentation plot was considered and two- to four-factor models were estimated. The weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) and also the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) method of estimation were employed. These are the methods suggested when working with ordinal variables that admit non-normal distributions (Rhemtulla et al., 2012; Schmitt et al., 2018). Geomin rotation was employed to facilitate the interpretation of the factors (Sass & Schmitt, 2010). Tucker-Lewis index (TLI > .95) and comparative fit index (CFI > .95), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.05, 90 % CI), and standardized root mean square error ratio (SRMR, < 0.05) (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Lloret et al., 2017).

A confirmatory analytical strategy was adopted for sample B (n = 221). The following models were evaluated using a confirmatory approach: 1) two factors: targeted policies and universal policies; 2) three factors: targeted beneficiary-centred policies, targeted contributor-centred policies, and universal policies; 3) four factors: beneficiary-centred targeted policies tending toward social welfare, beneficiary-centred targeted policies tending toward social advancement, contributor-centred targeted policies, universal policies; 4) second-order factory analysis: a second order dimension groups together targeted policy factors from model 3, which is linked to the universal policy factor. In the confirmatory analyses, the same estimation methods and overall fit indices were used as in the exploratory analyses. Covariance was admitted between errors of the same dimension after inspection of modification indices and residual analysis. The standardized regression coefficients of the best fitting model were interpreted. Finally, internal consistency was evaluated through Cronbach's alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951) and McDonald's omega coefficient (McDonald, 1970).

The programs MPlus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2011), R 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2018), and the MBESS package (v4.8, Kelley, 2007) were used.

Ethical aspects

The ethical guidelines for human research recommended by the American Psychological Association (2010) were followed. Individuals provided informed consent before completing the online survey and after receiving information about the conditions of anonymity, confidentiality, and voluntariness of participation.

Results

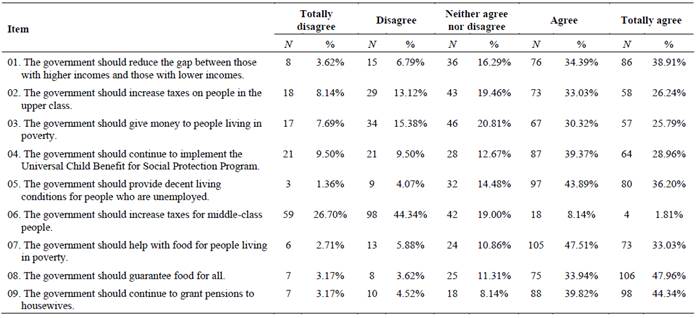

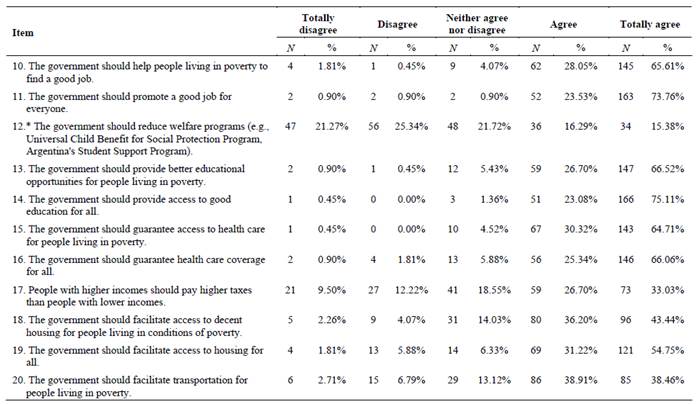

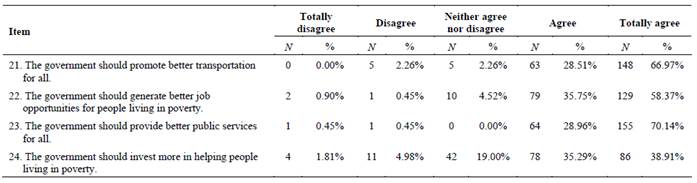

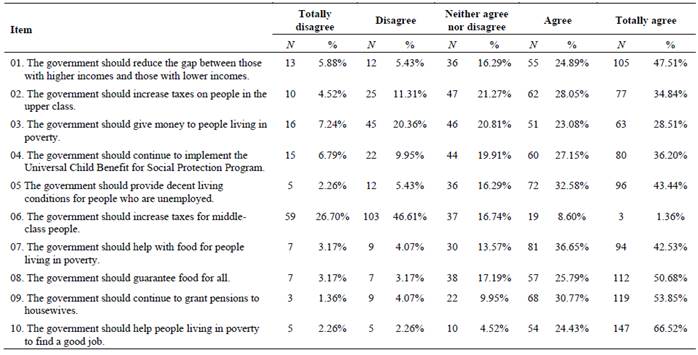

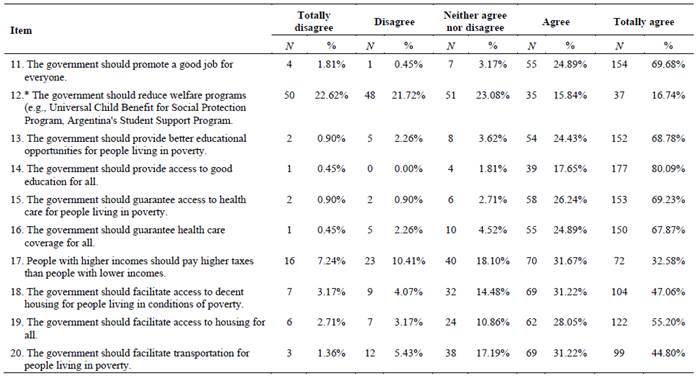

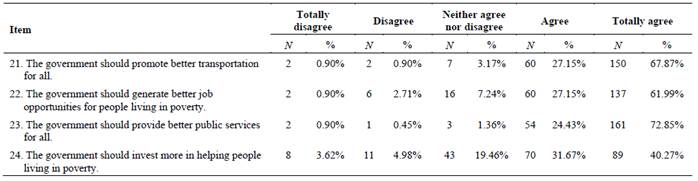

Descriptive analysis

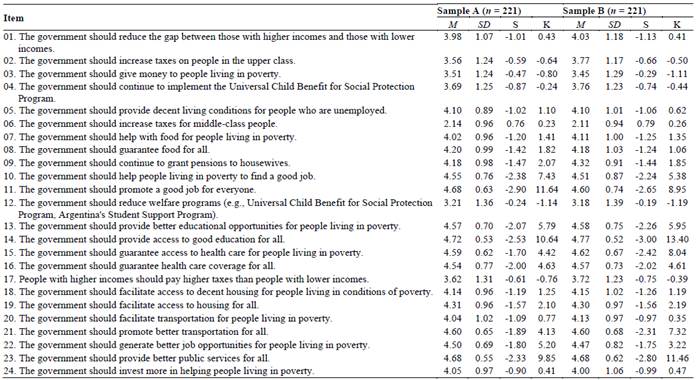

The items of each sample were analysed separately. Table 1 shows the values of M, SD, skewness, and kurtosis. Appendix B shows the frequencies. As can be seen in Table 1, almost all the items presented negative skewness, which indicates medium to high degrees of agreement with the different policies. Items 10, 11, 13, 14, 14, 15, 16, 19, 21, 22, and 23 showed high values of negative skewness and high kurtosis (higher by ± 1.5). Particularly, the items referring to a good job (item 11) and good education (item 14) for all showed a high degree of agreement. On the contrary, in both samples, item 6 referring to the increase in taxes for the middle class showed the lowest degree of agreement.

Factor analysis

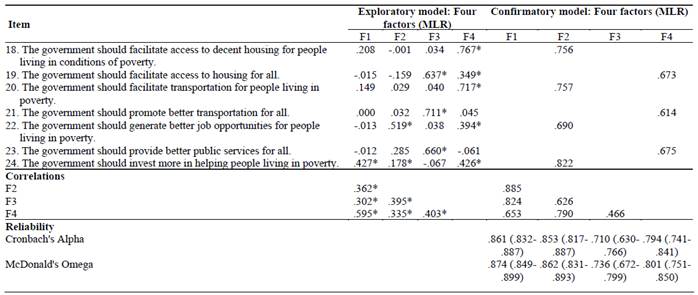

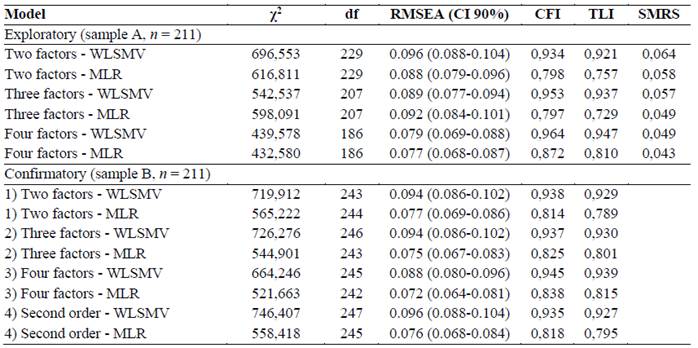

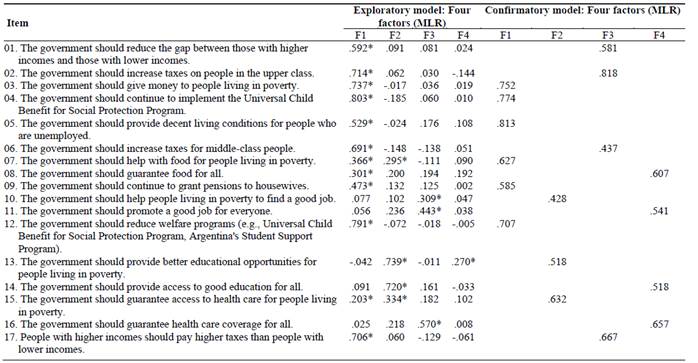

Table 2 shows the overall fit indices for the models evaluated in exploratory and confirmatory analyses. In the exploratory models, the sedimentation graph suggested the extraction of two factors. Two-to-four-factor models were evaluated. The four-factor model estimated with WLSMV showed an acceptable overall fit. However, inspection of the factor loadings revealed a complex matrix that was difficult to interpret in theoretical terms, and the second factor did not include items with high loadings. The three-factor model, which showed an acceptable overall fit only according to some overall indicators (CFI and TLI estimated with WLSMV), also presented a complex factorial matrix, with only one item with high loadings in the third factor. Table 3 T3b shows the factor loadings of the four-factor model with MLR estimator to demonstrate factorial complexity; similar results were obtained with WLSMV.

Regarding the confirmatory models, the four-factor model showed an acceptable fit (CFI and TLI estimated with the WLSMV method, and RMSEA estimated with MLR). Table 3 T3b shows the factor loadings derived from the model estimated with MLR, which is very similar to that obtained with WLMSV. The model involves clustering the items into the following dimensions: targeted beneficiary-centred policies that tend toward social welfare (6 items), targeted beneficiary-centred policies that tend toward social advancement (7 items), targeted contributor-centred policies (4 items), and universal policies (7 items). The relationship between the dimensions was .47 to .89.

Table 2: Overall fit indices for exploratory and confirmatory models of the attitude toward social policy ítems

Note: Confirmatory models: 1) Two factors: targeted policies and universal policies; 2) Three factors: targeted beneficiary-centred policies, targeted contributor-centered policies, and universal policies; 3) Four factors: beneficiary-centred targeted policies tending toward social welfare, beneficiary-centred targeted policies tending toward social advancement, etc., contributor-centred targeted policies, universal policies; 4) Second order: a second order dimension groups together targeted policy factors from model 3 and is linked to the universal policy factor.

Table 3: Exploratory and confirmatory factor loadings of attitudes towards social policies items and internal consistency índices

Discussion and Conclusions

The study of attitudes towards social policies contributes to the understanding of their support by citizens and their continuity over time. This research builds on a set of items collected in the literature on social policies relevant to the context in order to move towards the identification of latent dimensions. Thus, this is a complementary approach to the classic study based on single items.

In descriptive analyses prior to exploring the underlying dimensionality, a high level of agreement towards the different social policies was observed. The lower degree of agreement shown by item 6 (“The government should increase taxes for middle-class people”) may be associated with the high percentage of participants of that socioeconomic level in conjunction with the perception of people belonging to the middle class (Centro Estratégico Latinoamericano de Geopolítica (Latin American Strategic Center for Geopolitics), 2020; Elbert et al., 2020). In turn, the high degree of agreement in relation to item 14 that alludes to educational policies (“The government should provide access to a good education for all”) is noteworthy, a policy that is constituted as a way par excellence to reduce inequality (Tedesco, 2017).

The exploratory analyses did not provide acceptable overall fits. For the confirmatory analyses, dimensions that are commonly used to characterize social policies (targeted and universal) were considered. Furthermore, dimensions that facilitated the distinction between targeted policies focused on the beneficiary or on the contributor (Cavaillé & Trump, 2015) were taken into account. The whole research was framed within the particularities of the local context (targeted policies focused on the beneficiary that tend toward social welfare or social advancement, Home Arias, 2012).

The four-dimensional confirmatory model yielded an acceptable fit in most of the overall indicators considered, with the WLSMV estimator in CFI and TLI, and with MLR in RMSEA. This model distinguishes the following dimensions: targeted beneficiary-centred policies tending toward social welfare, targeted beneficiary-centred policies tending toward social advancement, targeted contributor-centred policies, and universal policies. All dimension items showed factor loadings above .40. The evidence of internal consistency is adequate or acceptable (above .80 or .70, respectively).

The multidimensionality would allow the assessment of individual differences in relation to social policies (García-Muniesa, 2019). In this sense, a person could agree with social advancement targeted policies but not with targeted social welfare policies. This type of evaluation would be a complementary way of analysing people's attitudes towards particular policies.

This work is not exempt from limitations. The first and foremost is that items were retrieved from different surveys that do not respond to a single model or theoretical perspective. Future studies could advance in the development of an instrument that assesses attitudes towards social policies in multidimensional terms in order to achieve a more comprehensive conceptualization of the construct. The second limitation, of a methodological nature, refers to the type of sampling employed, given that, being non-probabilistic, it makes it difficult to generalize the results. Thirdly, the lack of interdisciplinarity in the field of social policy measurement adversely impacts this work. Psychology, Sociology or Political Science address its study, but exchanges between them have rarely been generated, which generates confusion or lack of coherence between theoretical and empirical advances (Steele & Breznau, 2019). The present study tackles attitudes towards social policies from a particular branch of psychology, psychometrics. Although considered a valuable contribution, interdisciplinary work will hopefully allow us to overcome the difficulties in each discipline and achieve a better understanding of the construct of interest.

Finally, it should be noted that the study on attitudes towards social policies should be conducted considering that they are relative and dependent on the political, economic, and social systems of each country (e.g., the attitudes of citizens towards social policies vary in societies such as the United States or those of the Nordic countries; Steele & Breznau, 2019). Therefore, the situated evaluation of this construct considering the particularities of each context is important. This point cannot be ignored in Latin American countries, where social policies have been implemented as a way to reduce historical inequality.

In summary, this paper advances the understanding of attitudes toward social policies by seeking to identify singular dimensions of a complex construct. Recognizing the strong dynamic component of this construct, linked to the spatio-temporal characteristic of social policies, this study contributes not only to the field of study of social policies, but also constitutes available evidence to guide the political actions of governments.

REFERENCES

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (2005). The Handbook of Attitudes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Alesina, A. & Giuliano, P. (2009). Preferences for redistribution (Discussion Paper Series n.° 4056). Institute of Labor Economics. http://ftp.iza.org/dp4056.pdf [ Links ]

American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical principles of psychology and code of conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code [ Links ]

Boga, D. J. (2018). Apuntes acerca de la intervención social del Estado. El caso de las políticas sociales en Argentina. Margen: Revista de Trabajo Social y Ciencias Sociales, (90), 1-18. [ Links ]

Bráncoli, J. A. (2021). Hacia un sistema público de asistencia y cuidado en la post-pandemia. En W. Uranga (Ed.), Políticas Sociales: estrategias para construir un nuevo horizonte de futuro (pp. 9-19). Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de la Nación, Argentina. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/6367_-_libro_politicas_sociales_vol_2-web.pdf [ Links ]

Castillo, J. A. M., Marqués Perales, I., & Martínez Cousinou, G. (2011). Percepción de la desigualdad y demanda de políticas redistributivas en Andalucía. Colección Actualidad (Centro de Estudios Andaluces), 61, 1-27. [ Links ]

Castillo, J. C. & Olivos, F. (2014). Redistribución e impuestos: un análisis desde la opinión pública. En J. Atria (Ed.), Tributación en sociedad: impuestos y redistribución en el Chile del siglo XXI (pp. 143-165). Uqbar. [ Links ]

Cavaillé, C. & Trump, K-S. (2015). The two facets of social policy preferences. The Journal of Politics, 77(1), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1086/678312 [ Links ]

Centro Estratégico Latinoamericano de Geopolítica. (2020). Encuestas CELAG: América Latina en tiempos de pandemia. https://www.celag.org/encuestas-celag-america-latina-en-tiempos-de-pandemia/ [ Links ]

Comisión de Enlace Institucional. (2015). Cuestionario NSE Simplificado Online. https://www.saimo.org.ar/archivos/observatorio-social/CUESTIONARIO-NSE-Simplificado-Online-jun15.docx [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. (2018). La ineficiencia de la desigualdad. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. (2020). El desafío social en tiempos del COVID-19. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/45527/S2000325_es.pdf [ Links ]

Cronbach, J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555 [ Links ]

Cruces, G., Pérez-Truglia, R., & Tetaz, M. (2013). Biased perceptions of income distribution and preferences for redistribution: Evidence from a survey experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 98, 100-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.10.009 [ Links ]

Danani, C. (2017). Políticas sociales universales: una buena idea sin sujeto Consideraciones sobre la pobreza y las políticas sociales. Revista Sociedad, 37, 77-93. [ Links ]

De Sena, A. (Ed.). (2014). Las políticas hechas cuerpo y lo social devenido emoción. Lecturas sociológicas de las políticas sociales. Estudios Sociológicos Universitas Libros. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Argentina/iigg-uba/20150331024555/Las_politicas_ebook.pdf [ Links ]

Dimick, M., Rueda, D., & Stegmueller, D. (2018). Models of Other-Regarding Preferences, Inequality, and Redistribution. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), 441-460. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-091515-030034 [ Links ]

Duryea, S. (2016). Desafíos para políticas sociales en un contexto macroeconómico menos favorable. En L. Bértola & J. Williamson (Eds.) La fractura, pasado y presente de la búsqueda de equidad social en América Latina (pp. 611-629). Fondo de Cultura Económica de Argentina. [ Links ]

Elbert, R., Leiva, M. M., & Morales, F. S. (2020). ¿Cómo medir la identidad de clase? Una evaluación de dos formas de preguntar sobre pertenencia de clase en un estudio por encuesta. En R. Sautu, P. Boniolo, P. Dalle & R. Elbert (Eds.), El análisis de clases sociales Book Subtitle: pensando la movilidad social, la residencia, los lazos sociales, la identidad y la agencia (pp. 377-386). Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani. [ Links ]

European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure. (2018). ESS7 Data Documentation. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS7-2014 [ Links ]

Filgueira, F. (2014). Hacia un modelo de protección social universal en América Latina (Serie Políticas Sociales n.º 188). Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe y Gobierno de Noruega. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/35915 [ Links ]

García-Castro, J. D., González, R., Frigolett, C., Jiménez-Moya, G., Rodríguez-Bailón, R., & Willis, G. (2022). Changing attitudes toward redistribution: The role of perceived economic inequality in everyday life and intolerance of inequality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2021.2006126 [ Links ]

García-Muniesa, J. (2019). Preferences for redistribution in times of crisis: The role of fairness considerations and personal economic circumstances (Tesis de doctorado, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

García‐Sánchez, E., Osborne, D., Willis, G. B. & Rodríguez‐Bailón, R. (2020). Attitudes towards redistribution and the interplay between perceptions and beliefs about inequality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(1), 111-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12326 [ Links ]

Garriga, M. & Rosales, W. (2013). Finanzas públicas en la práctica. Selección de casos y aplicaciones. Dunken. http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/30300 [ Links ]

Home Arias, P. (2012). Caracterización del modelo de universalización y focalización utilizado en las políticas públicas. Revista Ciencias Humanas, 9(1), 97-111. [ Links ]

Hu, L. & Bentler (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 [ Links ]

Kelley, K. (2007). Methods for the Behavioral, Educational, and Social Sciences: An R Package. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 979-984. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192993 [ Links ]

Lloret, S., Ferreres, A., Hernández, A., & Tomás, I. (2017). The exploratory factor analysis of items: guided analysis based on empirical data and software. Anales de psicología, 33(2), 417-432. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.270211 [ Links ]

Martín-Artiles, A., Molina, O., & Meardi, G. (2011). Incertidumbre socioeconómica y actitudes hacia la inmigración en Europa. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 31(1), 167-194. https://doi.org/10.5209/revCRLA.2013.v31.n1.41645 [ Links ]

McDonald, R. P. (1970). Theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis and alpha factor analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 23, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1970.tb00432.x [ Links ]

Montero, I. & León, O. G. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7(3), 847-862. [ Links ]

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2011). Mplus User's Guide (6a ed.). [ Links ]

Ochman, M. (2014). Políticas sociales focalizadas y el dilema de la justicia. Andamios, 11(25), 147-169. [ Links ]

Plata, J. C. (2011). Perspectivas desde el Barómetro de las Américas: 2011. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/insights/I0861es.pdf [ Links ]

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org [ Links ]

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17, 354-373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315 [ Links ]

Sass, D. A. & Schmitt, T. A. (2010). A comparative investigation of rotation criteria within exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45(1), 73-103.https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170903504810 [ Links ]

Schmitt, T. A., Sass, D. A., Chappelle, W., & Thompson, W. (2018). Selecting the “best” factor structure and moving measurement validation forward: An illustration. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(4), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1449116 [ Links ]

Steele, L. G. & Breznau, N. (2019). Attitudes toward redistributive policy: An introduction. Societies, 9(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9030050 [ Links ]

Tedesco, J. C. (2017). Educación y desigualdad en América Latina y el Caribe. Aportes para la agenda post 2015. Perfiles educativos, 39(158), 206-224. [ Links ]

Vinocur, P. A. & Halperin, L. (2004). Pobreza y políticas sociales en Argentina de los años noventa. CEPAL. [ Links ]

Weihua, A. & Ye, M. (2017). Mind the gap: Disparity in redistributive preference between political elites and the public in China. European Journal of Political Economy, 50, 75-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.04.006 [ Links ]

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (National Agency for the Promotion of Research, Technological Development and Innovation) (# PICT2018-2980) and from the Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Secretariat of Science and Technology of the National University of Córdoba) (Consolidar 2018) awarded to the team coordinated by the first author.

Note: The authors Pablo Correa, Débora Jeanette Mola and María Victoria Ortiz contributed equally to this study and should be considered in second order of authorship, which is why they were ordered alphabetically by last name.

How to cite: Reyna, C., Correa, P., Mola, D. J., Ortiz, M. V. (2022). Attitudes towards social policies: from individual indicators to latent constructs. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2767. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2767

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. C. R. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; P. C. in b, c, d, e; D. J. M. in c, d, e; M. V. O. in c, d, e.

Received: December 21, 2021; Accepted: July 11, 2022

texto en

texto en