Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.16 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2022 Epub 01-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2692

Original Articles

Being an early childhood educator in times of uncertainty: challenges for professional development in context COVID-19

1 Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación, Chile, ignacio.figueroa_c2018@umce.cl

2 Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez, Chile

3 Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación, Chile

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged teachers and educational institutions to continue developing their pedagogical work despite the closure of their facilities, seeking alternatives for it. This article seeks to understand how a group of Chilean nursery school teachers adapt their professional actions to the demands of the pandemic. This article is part of a broader qualitative study, of a narrative nature, and focuses on the experiences of six professional practicing educators, through semi-structured interviews, which were studied through a thematic analysis. Four main themes were found to constitute challenges for their professional learning: (1) uncertainty and coexistence of roles, (2) the mastery of technologies for remote learning, (3) the relationship with families and (4) pedagogical tensions around virtual teaching in early childhood contexts. These four categories are articulated around the need to train and accompany educators to provide better responses to teaching in contexts of uncertainty, while at the same time the need to recognize the work of early childhood educators for our society emerges.

Keywords: COVID-19; pandemic; early childhood education; teacher identity; professional development

La pandemia por la COVID-19 desafió a docentes e instituciones educativas a continuar desarrollando su trabajo a pesar del cierre de sus instalaciones, lo que los llevó a buscar alternativas pedagógicas. Este artículo busca comprender cómo un grupo de educadoras de párvulos chilenas han experimentado las demandas de la pandemia en su accionar profesional. Este artículo es parte de un estudio cualitativo más amplio, de corte narrativo, y focaliza en las experiencias de seis educadoras experimentadas en ejercicio, a través de entrevistas semiestructuradas estudiadas por un análisis temático. Se encontraron cuatro temas principales que constituyen desafíos para su aprendizaje profesional: (1) la incertidumbre y coexistencia de roles, (2) el dominio de las tecnologías para el aprendizaje remoto, (3) la relación con las familias, y (4) las tensiones pedagógicas en torno a la enseñanza virtual en contextos de primera infancia. Estas cuatro categorías se articulan en torno a la necesidad de formar y acompañar a las educadoras para dar mejores respuestas a la enseñanza en contextos de incertidumbre, al mismo tiempo que emerge la necesidad de reconocer el quehacer de las educadoras de párvulos para nuestra sociedad.

Palabras clave: COVID-19; pandemia; educación infantil; identidad docente; desarrollo profesional

A pandemia da COVID-19 desafiou professores e instituições educacionais a continuar a desenvolver seu trabalho pedagógico apesar do fechamento de suas instalações, buscando alternativas para seu trabalho pedagógico. Este artigo procura entender como um grupo de educadores chilenos da primeira infância adaptam suas ações profissionais às exigências da pandemia. Este artigo é parte de um estudo qualitativo mais amplo, de natureza narrativa, e enfoca as experiências de seis educadores praticantes experientes por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas, que foram estudadas através de uma análise temática. Quatro temas principais foram considerados como desafios para sua aprendizagem profissional: (1) incerteza e coexistência de papéis, (2) domínio de tecnologias para aprendizagem à distância; (3) relação com as famílias; e (4) tensões pedagógicas em torno do ensino virtual nos contextos da primeira infância. Estas quatro categorias são articuladas em torno da necessidade de treinar e acompanhar educadores a fim de oferecer melhores respostas ao ensino em contextos de incerteza, ao mesmo tempo em que emerge a necessidade de reconhecer o trabalho dos educadores da primeira infância para nossa sociedade.

Palavras-chave: COVID-19; pandemia; educação infantil; identidade do professor; desenvolvimento profissional

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all sectors of society, exposing limitations in our educational systems (Fullan et al., 2020). To reduce the risk of contagion, educational institutions closed, continuing their pedagogical work remotely, an approach that implies that students are not physically present in the institution (Muñoz & Lluch, 2020), carrying out the pedagogical activities from their homes.

In this context, the lockdown experience forced educational communities to rethink their practices and adapt to new environments (González et al., 2020). In this process, research shows a distressing experience from teachers, as they perceived a neglected attitude from the educational administration, with improvised responses, without resources, training or ways to develop their pedagogical work (Molina & Pulido, 2021). Remote teaching implied changes in teachers’ and students’ roles, intensifying families’ participation as nexus or spectators of the process (Muñoz & Lluch, 2020).

When educational centers closed, Rojas et al. (2021) describe a crisis of care, where women assumed exclusively the responsibility of childcare in their homes, amplifying gender inequality and the feeling of discomfort due to simultaneous development of productive and care activities.

In early childhood (EC) education, there are particularities that complicate the educational process. At this level, pedagogical work is difficult to address remotely (Ruiz et al., 2020) given that teacher-child interaction requires face-to-face contact to promote learning based on trust and emotional security (Zuloaga, 2019). This caused distress among teachers’ teams, who had to generate strategies to achieve requirements. In this sense, collaboration with families was essential, as children require support for the pedagogical activities proposed remotely (Quinones et al., 2021).

In addition, EC education is a highly feminized sector, associated with care and welfare (Olave, 2020; Poblete, 2018). Furthermore, teachers experience tensions with an early schooling process demanded by the accountability policy, which restricts their decision-making, limiting their actions to the classroom where they can maintain an education approach based on play and emotional bonding, but without influence from educational policies (Pardo & Opazo, 2019).

In regular contexts, the EC teacher’s work is highly emotional, which demands self-regulation to generate comfortable interactions with children (Fu, 2015). During the pandemic, this situation was accentuated as teachers perceived a devaluation of their professional work from families, threatening their emotional well-being (Quinones et al., 2021). This is a scenario in which, for EC teachers, a lack of work regulation, low salaries and a fragile professional status coexist (Arteaga et al., 2018; Pardo & Opazo, 2019; Poblete, 2018).

The interpretation that EC teachers make of their roles will depend on their own experiences and the ways they define themselves in a particular context. Consequently, their identities are constructed in a process of continuous negotiation between the subjectivity and objectivity of their work (Olave, 2020). For Poblete (2018), among the tensions EC educators experience are exploitation and admiration and representing themselves as altruistic, devoted and self-sacrificing women, which contradicts the professionalization of EC education.

This study seeks to know how a group of EC teachers developed their praxis in the disruption of their daily work (Sardí, 2013) in the context of the pandemic. That, according to Hanna et al. (2019), implies tensions, imbalances, crises or new elaborations, which generate conflicts between the perceived situation and the standard professional identity, promoted by teacher education and public policy. This is based on the understanding that professional identity implies a process that evolves, that is constructed and reconstructed in interaction with people, institutions, and cultural contexts (Rodgers & Scott, 2008) and that for Beijaard et al. (2004) implies a contextualized interpretation and reinterpretation of their experiences. The above implies, according to Sarceda (2017), a search for meaning in their work, linked to a conscious and systematic reflection to promote professional learning (Korthagen, 2017).

The educational impact of the pandemic has aroused academic interest, inspiring research on developing research about teaching in an emergency and remote education considering emotional aspects, institutional support or professional competencies required for these contexts (González et al., 2020; Molina & Pulido, 2021; Ramos et al., 2020; Ruiz et al., 2021; Quinones et al., 2021). However, there are few studies that address the issue at the EC level in Chile. The aim of this article is to understand how a group of EC educators experienced the complexities of their professional practice in the COVID-19 context.

Materials and methods

This study adopts a qualitative approach with a descriptive and interpretative scope (Aguirre & Jaramillo, 2015), which seeks to understand the experiences of a group of EC educators and their work in the context of the pandemic. The method corresponds to a multiple case study with narrative orientation (Riessman, 2008), since it seeks to explore the experience, facilitating the construction of meaning and addressing their memories considering the relationships with other aspects of their subjectivity (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The participants were selected by a purposive sampling based on specific criteria (Flick, 2015) that include: a degree as an EC teacher, experience as educators, i.e., having more than five years of work experience (Freeman, 2001) and working in EC education.

Participants

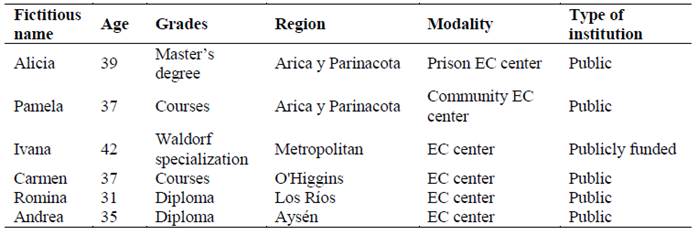

The study included six educators, between 31 and 42 years of age (M= 36.8) who work in different regions of Chile with children between three months and four years, five of which are publicly administered, and one is private but administered through the transfer of public funds. Two of the groups work in non-conventional modalities: a prison and a community EC center. In terms of professional development, one teacher has a master’s degree, two have diplomas, one has specialized courses in Waldorf pedagogy and the other two educators studied short courses. It was decided to give variability to the production of experiences, both in the institution and modality, as well as in the region, considering the different scenarios and otherness present (Table 1).

Instruments for the production of information

Semi-structured interviews of narrative nature were conducted between the second semester of 2020 and the first semester of 2021. The script was organized following Sarceda's (2017) proposal considering questions and interactions throughout the different life stages of each educator: childhood/adolescence, initial teacher education, work as a teacher and the present area on which this article focuses. The instrument was validated by three doctors in education who work as researchers, adjusting its questions and redaction. The interviews were remotely developed to each educator in three sessions of one hour each, in which the experience during the first year of the pandemic was mainly addressed. In all the cases, this first year of pedagogical work during the pandemic was carried out remotely, as required by the authorities.

Analysis of the information

After the transcription of the interviews, a thematic narrative analysis (Riessman, 2008) was carried out, based on the experiences reported by each educator. An open coding process was carried out for each case, identifying those situations and emotions experienced, as well as the actions performed. Subsequent inductive categories were generated, configuring the major themes addressed by the teachers in their narratives.

Following Braun’s and Clarke’s recommendations (2006), the next step was a revision of the pertinence of codes and categories, based on reading and validation of the research team, ensuring that the issues raised were appropriate. To support the categories, participants’ quotations were included. The qualitative data analysis software Atlas Ti. 8 © was used.

Ethical considerations

The research followed the ethical guidelines of negotiation, collaboration, confidentiality and anonymity, equity, impartiality and commitment to knowledge (Flick, 2015), respecting the integrity of the participants, who signed an informed consent validated by the ethics committee of the Universidad de Santiago. For anonymity purposes each teacher was assigned a pseudonym.

Results

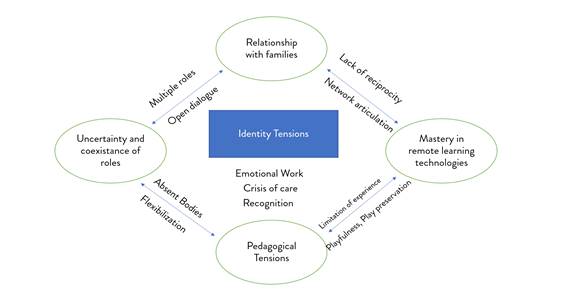

The analysis reveals four main themes in relation to the challenges of pedagogical practice in pandemic contexts: (a) Uncertainty and coexistence of roles, (b) Mastery of technologies for remote learning, (c) Relationship with families, (d) Pedagogical tensions.

Uncertainty and coexistence of roles

The educators described the restructuring process of their professional role, linked to the absence of their usual space: the classroom. The foundations and key principles of their practices were questioned, such as affection and physical contact. The experience of the pandemic was described as a strange and disturbing situation, to which the educators initially responded with disorientation and distress, which was especially evident in those teachers who did not know the children or their families, since they were beginning the educational year.

It happened that we started enthusiastically, then came this disorientation (…) what can we do and there I was more or less two weeks in limbo, I did not know what to do (…), whether to evaluate or not to evaluate, how to contact the families, how to communicate with them, I was just getting to know them, there was no connection, there was no trust, nothing, nothing (Andrea).

In this sense, isolation and the impossibility of "being there" with the children implied an important emotional loss as they were unable to support the children. The educators perceived that face-to-face work allowed them to make a difference in terms of the children's trajectories, so the condition of uncertainty affected them emotionally.

I think it was a process of the pandemic, of not being able to work in person with the children, knowing that there are conditions that are very adverse in their lives, which one resents it a lot (Ivana).

During the first year of the pandemic, pedagogical work was done remotely from the teachers’ homes, through videoconferences or videos with pedagogical experiences. Working virtually, teachers had to adjust their professional roles with their family lives, implying emergent situations in which the educators had to coordinate personal and professional demands.

It was terrible because it was very difficult for me to reconcile everything. Being a mother, working, seeing to housework, and now all day long, I run from the moment I get up to the moment I go to bed (…). It has been really difficult for me (Carmen).

In addition, in the context of uncertainty during the first year of the pandemic, the educators experienced discomfort and emotional oscillation as a result of the need to adequately respond in a social context highly stressed by the pandemic and the potential risk of contagion of the population.

Going through different emotions, different sensations (…). There were prejudices, there was fear, from a professional and a personal point of view. There were many stages that I went through, first... like the emotional comedown (…) “Ah, I feel like I don’t want to do anything”. Then the activity: “Ah, I have to sanitize everything, because we are going to catch it, we are going to get COVID” (Andrea).

In this sense, sadness also emerged showing high expectations for a return that never materialized. In this sense, the educators are perplexed by the evolution of their educational tasks, questioning their educational function and at the same time disappointed by the working conditions in a context of uncertainty.

There is this discourse that the team members are very important, that we have to be well first so that the children can be well. But it turns out that (…), in practice, this was not carried out or respected, so, of course, many hearts were hurt and disappointed (Romina).

Mastering remote learning technologies

A primary challenge in the pandemic scenario was to adapt to the context of remote learning and to demonstrate mastery of information technologies. This was particularly important to keep contact with the children and their families to continue their pedagogical work. One of the educators refers to this situation:

In a certain way, all of us had to know and internalize the subject of ICTs or, for example, when we wanted to organize something with the parents, when we had to send them the strategies, the way we were going to approach the children, how we were going to send them the games we wanted to bring them (Romina).

The mastery of technologies refers to synchronous communication platforms that were not usual in their practice and required learning oriented to the development of their pedagogical experiences. An educator goes into more detail below:

Well, in the case of (…) knowing these types of platforms such as Zoom, Teams, it was not something that one uses daily, so it still requires learning (Alicia).

In this sense, the educators pointed out that initially they did not receive the necessary training from their institutions to approach online teaching. Faced with the lack of knowledge and education, teachers sought self-managed alternatives to develop their expertise in emergency contexts. In the case of Alicia, for example, there was a process of technological transfer from the children of another teacher, who already had experience and skill using their schools' platforms. This resource was extended to the rest of the teachers’ staff.

One of the teachers has a son, who is very young, and he was much more skilled in using this platform than we were. In fact, he taught us because he had classes, and he started much earlier. And he showed us the alternatives and how we could use it better (Alicia).

In terms of training in technologies, this process has implied a new professional learning, while it has provided opportunities to access new educational experiences.

I think that more time has also been given to read, to learn about other pedagogies. I am doing a seminar, and I have more time to study for that seminar, to connect to the classes... (Ivana).

Relationship with families

A third area described is the relationship with families. During the pandemic relationships changed in several ways. The teachers reported a more direct communication, mainly because formalities were abandoned to access the children’s lives and by extension their families. Due to remote teaching, the educators reported a main role of the families since they become “intermediaries” of their pedagogical action, by preparing the conditions for a synchronous interaction or sharing the audiovisual material sent by the teachers.

We also try to generate instances with the babies, the baby with the mother, and to be able to show them strategies, because children learn by playing direct interaction. So there was little we could do with the children, but with the mothers, to provide them with strategies, to make sense of the work and stimulation they are doing daily (Alicia).

Teachers reported that they would communicate with families through social networks, email, and phone calls. The main means of communication has been WhatsApp, given its accessibility and immediacy. To communicate with families, educators expanded the limits of the professional relationships, showing themselves as welcoming, close, and available. Notwithstanding, this experience was not easy because some families would not act reciprocally, not responding to their pedagogical requirements.

I think that when they ignore you on WhatsApp it is like the worst thing that can happen, they ignore you and don't give you okay, nothing; you don't know, then, because you interpret (…) and I say: “Oh, he/she didn't like it, he/she got angry, he/she didn't have time to respond, he/she had an accident, what do I know... he/she dropped the phone and then forgot it” (Andrea).

To solve the lack of reciprocity, the teachers would take a position and act reflexively and collaboratively to understand the scenario and respond to the context. The answers given by the educators were collegial and implied the need to articulate a relevant proposal based on open and direct communication.

Then, after discussion about this situation and after a long time, it was like, what can we do, what strategy can we look for, how can we motivate, how can we encourage participation? (Andrea).

In this way, it was important for the educators to have access to the families’ lifeworld’, building a relationship of accompaniment and support. This close and concerned inquiry allowed them to bring the pedagogical process closer, giving its own meaning, by getting into the impact of the pandemic in families’ daily lives, although they perceived that virtual relationships were not comparable to the face-to-face experience.

We communicated a lot by email, by WhatsApp (…). Suddenly due to the evaluations, they had to send me evidence of the activities they did at home and the file size was heavy, the email did not work, they sent it to WhatsApp. So strategy changed, but it is different, it is different to connect with the family in person, to be with them, an email for me, at least, is colder (Romina).

The educators considered different innovations such as brief synchronous sessions with the children and their families or meetings designed flexibly to meet the needs of families. For example, in Pamela's case, there was an emerging space for reflection in a project called "virtual toy libraries", in which they addressed topics of interest with the families, becoming, in addition, an instance of emotional support.

So, in every session we talk about different topics that families and we propose (…) and it has been such a rich space. I think that the good thing about the pandemic has been that, and the families value it and say, “We never had this before, we could never talk at this level” (Pamela).

Pedagogical tensions

In relation to the implementation of remote pedagogy, tensions were reported regarding the adjusting of their teaching practices to this modality. There were a suspicion regarding the scope of an unknown teaching modality and the suppression of sensitive aspects of the concrete experience, which in the beginning led to questioning of the possibility of educating children this way. In addition, there was tension over the evaluations, since they were sometimes not returned by the families, which interrupted the pedagogical tracing. There was a need to work, in parallel to the learning objectives, on the emotional issue.

It did not bother me to do videos, for example, what was more complicated was the issue of evaluations and (…) time organization, and how this, in turn, was worked on in parallel because of how one feels emotionally in this pandemic (Romina).

To resolve these tensions, tools such as a playful attitude and histrionics emerged in remote pedagogical experiences. The mechanisms used included audiovisual capsules and synchronous meetings. These showed the need to operate pedagogically from a theatrical show to emulate the face-to-face experience and sustain the attention and interest of children.

How do I transmit this? First, I have to like what I am going to transmit in the capsule, I have to show that I am having a great time and that, I have to transmit it. Second, the children have to relate to me, they do not know me, how can they relate to me if I am very serious and talk to them in a very technical way, I have to be close and how, my face, smile, open my eyes, gesticulate. Third, I have to look at the camera, because they are there, I have to imagine that they are there, so I can no longer look to the side or down, I am looking at them. So, I practiced a little bit at a time and then it came naturally (Andrea).

This adaptation to virtual contexts implied in Ivana's case a transaction with the pedagogical principles that inspired her actions. She criticizes the use of screens at early ages and the impossibility of being with the other, together with the notion of experience that is at the basis of her pedagogy.

It is not the same as experiencing it, in this case it is felt, it is resented as not being next to the other, being able to listen, to be able to look at him/her, I think that in Waldorf pedagogy it is fundamental to be together and make community, to be able to look at each other, to be able to know how they are when we start a class (Ivana).

This tension implied, at the beginning, a negotiation of meanings in which an emergency situation was imposed, having to rescue central aspects of each pedagogy, such as the notion of autonomy and adult accompaniment as axes of teaching practice in virtual mode.

Discussion

This research aimed to understand the experiences of a group of EC teachers in the COVID-19 context. The findings show four emerging themes that, in agreement with Ruiz et al. (2021), report the coexistence of educational and care work, the intensive work with families, as well as the adjustments to didactic planning including technologies during the lockdown period. In this sense, teachers experienced emotional fluctuations with disorientation, anguish, and sadness. The uncertainty of the situation implied the blurring of boundaries between personal and professional roles, since, as Durán (2020) points out, when the home is used as a workplace, potential conflicts are revealed. Among these overlapping roles are those of care in their own homes, given the rupture of support networks due to the lockdown processes (Rojas et al., 2021) and the role of care support to families (Ruiz et al., 2021). In addition, the narrative shows the fear of the pandemic's progress, the impossibility of being with the children in the classroom and the expectation of a return to the classroom, which did not materialize until the pandemic’s second year.

Regarding the mastery of technologies, educators responded by actively adapting to working remotely through self-management. In this sense, educators reported a lack of support from the educational system, which acted reactively, with pedagogical improvisation (Molina & Pulido, 2021). Despite the above, the pandemic was perceived by the educators as a scenario that allowed them to learn new pedagogical competencies that they had to integrate to their support and articulate network’s roles for the children’s benefit.

In the search to adapt to working remotely, it was necessary for the educators to extend their work to the family, who operated as “intermediaries” of the pedagogical function. In this sense, a series of problems were observed, which showed the need to re- culturing the educational community and promote learning in emergency contexts (Fullan et al., 2020), as well as to conduct a process of recognition of the teachers’ role (Quinones et al., 2021) and of the notion of care as a shared process (Rojas et al., 2021). This is especially important, considering the characteristics of the educational level, where the articulation between care and pedagogy is key, which required expanding and addressing the critical situation that implied the change in the habits and daily life of families and educators due to the pandemic.

In relation to the pedagogical tensions experienced by the educators, they were linked to the initial suspicion about the viability of screen-mediated education. Problems were reported regarding pedagogical evaluations and the approach to socioemotional issues without face-to-face contact and expressions of physical affection. Thus, in their remote interactions, educators had to display histrionics, theatricality and good humor, showing a playful attitude, favorable for children's learning (Singer, 2013). In the narrative of the educators, an adjustment and flexibility of their practice could be appreciated, re-elaborating beliefs about virtual teaching and the professional link with families, promoting an open dialogue, sensitive to contingencies. In this sense, more than just using sophisticated technology (Iriarte et al., 2021; Ruiz et al., 2021), educators have expanded the notion of innovation by developing a media competence, which was based on good communication, expression and management of shared knowledge.

Thus, in the COVID-19 context, teachers experienced identity tensions (Hanna et al., 2019) by resituating their teaching practice in an adverse context that contradicts key principles in EC education: the presence of the body and affection (“Being there”), well-being, play, progressive autonomy, and mediating accompaniment. In this sense, the areas of uncertainty (Sardí, 2013) experienced by the educators were addressed with actions that reaffirm the relevance of EC education for children's trajectories. The above is linked to the identity validation linked to the search for meaning (Sarceda, 2017) and the intention to preserve child-centered pedagogy as a central element in the teachers’ identity (Pardo & Opazo, 2019). This situation informs about the need to explore the construction of professional identity in the work context and how it is rearticulated according to contextual requirements and contemporary demands (Beijaard et al., 2004; Rodgers & Scott, 2008).

It is also relevant to identify the emotional work developed by educators (Fu, 2015), who had to regulate their emotions, giving up, on many occasions, their privacy and rest, to provide support to children and their families. This shows an identity construction that emerges from the postponement of their place in the world, to devote themselves to their mission of child protection (Poblete, 2018). In this sense, it is necessary for institutions to deploy strategies to mitigate the effects and emotional sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ramos et al., 2020), aiming to ensure conditions of well-being and recognition for educators (Arteaga et al., 2018; Quinones et al., 2021) and to strengthen spaces for reflection that allow for situated and collaborative professional learning (Korthagen, 2017).

The above can be seen in figure 1 , which summarizes the interconnections between the situations and the actions performed by the teachers.

It is necessary to analyze these situations in the different communities of practice, addressing the care crisis from a gender perspective (Rojas et al., 2021), by promoting solidarity among educators and their teams (Quinones et al. 2021) and questioning professional postponement (Poblete, 2018). This implies coordinating collaborative efforts to promote harmonious, safe and stable interactions, which is a key factor for child development (Zuloaga, 2019). In this sense, the narrative approach to social situations (Riessman, 2008; Sardí, 2013; Sardí & Andino, 2013) constitutes a tool with high potential as it stimulates the incorporation of subjectivity in preservice and in-service teacher education, as a relevant aspect in the process of building teacher identity.

Conclusion

This research shows four themes for the group of EC teachers, which are (1) uncertainty and coexistence of roles, (2) the mastery of information technologies, (3) relationships with families, and (4) pedagogical tensions related to the adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

These results describe the need to address teachers' professional development the conditions for learning to live in times of uncertainty, with discontinuous time and in the disjunction of the relationship between the self and the other (Britzman, 2007). It is a priority to address what cannot be understood, placing at the center a humanitarian sense in which care and well-being are values that guide the pedagogical transformation of EC education. These findings are relevant to enrich the teachers’ professional by interweaving personal and professional biographies and academic and vital experiences (Sardí & Andino, 2013).

The above values the need to understand and reflect situatedly and consciously (Korthagen, 2017) the triad emotion-body-affectivity, showing the need to overcome individualism and desire for individual success present in the Chilean educational system (Muñoz, 2020), and educate flexible teachers who respond critically to changing contexts. At the same time, this study highlights the need for greater recognition of the teacher’s role in EC education (Arteaga et al., 2018; Pardo & Opazo, 2019; Poblete, 2018; Quinones et al., 2021; Sarceda, 2017; Scherr & Johnson, 2017).

It is expected that these findings will contribute to a better understanding of the experience of EC teachers in Chile, reporting the need to enhance, from educational institutions and policies, the conditions for teaching work in EC education.

REFERENCES

Aguirre, J. C. & Jaramillo, L. G. (2015). El papel de la descripción en la investigación cualitativa. Cinta de moebio, (53), 175-189. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-554X2015000200006 [ Links ]

Arteaga, P., Hermosilla, A., Mena, C., & Contreras, S. (2018). Una mirada a la calidad de vida y salud de las educadoras de párvulos. Ciencia y trabajo, 20(61), 42-47. [ Links ]

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and teacher education, 20(2), 107-128. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Britzman, D. P. (2007). Teacher education as uneven development: toward a psychology of uncertainty. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(1), 1-12. [ Links ]

Durán, N. I. (2020). El Teletrabajo y la conciliación con el entorno de convivencia familiar durante la Pandemia COVID-19. Revista de Investigación Psicológica , ( ESPECIAL), 68-72. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2015). El diseño de la investigación cualitativa. Morata. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (2001). Second language teacher education. En R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 72-79). Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fu, C. S. (2015). The effect of emotional labor on job involvement in preschool teachers: Verifying the Mediating Effect of Psychological Capital. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 14(3), 145-156. [ Links ]

Fullan, M., Quinn, J., Drummy, M., & Gardner, M. (2020). Educación reimaginada; El futuro del aprendizaje. New Pedagogies for Deep Learning y Microsoft Education. https://deep-learning.global/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TRADUCCION-Education-reimagined.-The-future-of-learning-NPDL-2020.pdf [ Links ]

González, G., Barba, R. A., Bores, D., & Gallego, V. (2020). Aprender a ser docente sin estar en las aulas: La covid-19 como amenaza al desarrollo profesional del futuro profesorado. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 152-177. https://doi.org/10.17583/rimcis.2020.5783 [ Links ]

Hanna, F., Oostdam, R., Severiens, S. E., & Zijlstra, B. J. (2019). Primary student teachers’ professional identity tensions: The construction and psychometric quality of the professional identity tensions scale. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 61, 21-33. [ Links ]

Iriarte, M., Rivera, D., & Celly, S. (2021). La competencia mediática en la educación infantil en Ecuador. GIGAPP Estudios Working Papers, 8(190-212), 50-63. [ Links ]

Korthagen, F. A. (2017). A foundation for effective teacher education: Teacher education pedagogy based on situated learning. En The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 528-544). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402042.n30 [ Links ]

Molina, J. & Pulido, C. (2021). COVID-19 y digitalización “improvisada” en educación secundaria: Tensiones emocionales e identidad profesional cuestionada. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 10(1), 181-196. https://doi.org/10.15366/riejs2021.10.1.011 [ Links ]

Muñoz, G. (2020). Experiencia de educación emocional en la formación de las educadoras de párvulos. Revista de estudios y experiencias en educación, 19(39), 45-55. https://doi.org/10.21703/rexe.20201939munoz3 [ Links ]

Muñoz, J. & Lluch, L. (2020). Educación y Covid-19: Colaboración de las Familias y Tareas Escolares. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 9(3). [ Links ]

Olave, S. (2020). Revisión del concepto de identidad profesional docente. Revista Innova Educación, 2(3), 378-393. https://doi.org/10.35622/j.rie.2020.03.001 [ Links ]

Pardo, M. & Opazo, M. J. (2019). Resisting schoolification from the classroom. Exploring the professional identity of early childhood teachers in Chile. Cultura y Educación, 31, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2018.1559490 [ Links ]

Poblete, X. (2018). Performing the (religious) educator’s vocation. Becoming the “good” early childhood practitioner in Chile. Gender and Education, 32(8), 1072-1089. http://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1554180 [ Links ]

Quinones, G., Barnes, M., & Berger, E. (2021). Early childhood educators’ solidarity and struggles for recognition. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 46(4), 296-308. https://doi.org/10.1177/18369391211050165 [ Links ]

Ramos, V., García, H., Olea, C., Lobos, K., & Sáez, F. (2020). Percepción docente respecto al trabajo pedagógico durante la COVID-19. CienciAmérica, 9(2), 334-353. http://doi.org/10.33210/ca.v9i2.325 [ Links ]

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage. [ Links ]

Rodgers, C. R. & Scott, K. H. (2008). The development of the personal self and professional identity in learning to teach. En M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 732-755). Routledge. [ Links ]

Rojas, S, Energici, M., Schöngut, N., & Alarcón, S (2021). Im-posibilidades del cuidado: reconstrucciones del cuidar en la pandemia de la covid-19 a partir de la experiencia de mujeres en Chile. Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología, 45, 101-123. https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda45.2021.05 [ Links ]

Ruiz, A. M., Picazo, M., & Cotan, A. (2021). Docentes en remoto: Una investigación narrativa sobre la labor de escuelas infantiles durante el confinamiento. En B. Puebla-Martínez & R. Vinader-Segura (Coords.), Ecosistema de una pandemia: COVID 19, la transformación mundial (pp. 1771-1785). Dykinson. [ Links ]

Sarceda, C. (2017). La construcción de la identidad docente en educación infantil. Tendencias pedagógicas, (30), 281-300. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2017.30.016 [ Links ]

Sardí, V. & Andino, F. (2013). Marcas biográficas en la escritura de incidentes críticos En V. Sardí (Coord.). Relatos inesperados: La escritura de incidentes críticos en la formación docente en letras (pp. 56-75). Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata. [ Links ]

Sardí, V. (2013). La escritura de las prácticas en la formación docente en letras. En V. Sardí (Coord.), Relatos inesperados: La escritura de incidentes críticos en la formación docente en letras (pp. 10-32). Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata . [ Links ]

Scherr, M. & Johnson, T. G. (2017). The construction of preschool teacher identity in the public-school context. Early Child Development and Care, 189(3), 405-415. [ Links ]

Singer, E. (2013). Play and playfulness, basic features of early childhood education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21, 172-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2013.789198 [ Links ]

Zuloaga, M. L. (2019). Interacciones significativas para el desarrollo humano. Avances en Psicología, 27(2), 123-134. [ Links ]

How to cite: Figueroa-Céspedes, I., Guerra Zamora, P., & Madrid Zan, A. (2022). Being an early childhood educator in times of uncertainty: challenges for professional development in context COVID-19. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2692. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2692

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. I.F-C. has contributed in con a, b, c, d, e; P. G. Z. in d, e; A. M. Z. in e.

Received: October 04, 2021; Accepted: July 15, 2022

texto en

texto en