Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.16 no.1 Montevideo 2022 Epub 01-Jun-2022

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i1.2364

Original Articles

The work of liberal health professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic context

1 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas, Brasil

2 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas, Brasil

3 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas, Brasil

4 Universidad Católica del Uruguay, Uruguay, jlabarth@ucu.edu.uy

As of March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic made an important impact on work on a global scale. In the absence of a vaccine, the most adopted measures were social distance and preference for remote work. The present study sought to understand the meanings that eight health professionals attributed to their practices in this context. Meetings held with a dentist, a physician, an occupational therapist, a nurse, a psychologist, a physiotherapist, a speech therapist, and a nutritionist, were registered through comprehensive narratives. Three categories of results were found: 1) the meaning of work, 2) the option for liberal practice, and 3) the implications of the pandemic. It was possible to see how the effects of the pandemic were peculiarly experienced by each of the participants, in some cases making them reconsider the meaning of work in their lives.

Keywords: labor psychology; health professionals; COVID-19 pandemic; phenomenology

A partir de março de 2020 a pandemia da COVID-19 gerou importantes impactos sobre o trabalho em escala mundial. Diante da inexistência de uma vacina, as medidas mais adotadas foram o distanciamento social e preferência pelo trabalho remoto. O presente estudo buscou compreender quais significados que oito profissionais liberais da área da saúde estavam atribuindo aos seus ofícios em meio a esse contexto. Foram realizados encontros dialógicos com um odontólogo, um médico, uma terapeuta ocupacional, uma enfermeira, um psicólogo, uma fisioterapeuta, uma fonoaudióloga e uma nutricionista registrados por meio de narrativas compreensivas. Três categorias de resultados foram encontradas: 1) o significado do trabalho, 2) a opção pela atuação liberal e 3) as implicações da pandemia. Foi possível constatar como os efeitos da pandemia foram sendo vividos de maneiras peculiares por cada um dos participantes e fazendo-os repensar, em alguns casos, o significado do trabalho em suas vidas.

Palavras-chave: psicologia organizacional; profissionais de saúde; pandemia do COVID-19; fenomenologia

A partir de marzo de 2020, la pandemia COVID-19 causó importantes impactos en el trabajo a escala global. A falta de una vacuna, las medidas más adoptadas fueron la distancia social y la preferencia por el trabajo a distancia. El presente estudio buscó comprender qué significados atribuían ocho profesionales de la salud a su trabajo en este contexto. Se realizaron encuentros en los que se dialogó con un dentista, un médico, una terapeuta ocupacional, una enfermera, un psicólogo, una fisioterapeuta, una logopeda y una nutricionista, registrados a través de relatos exhaustivos Se encontraron tres categorías de resultados: 1) el significado del trabajo, 2) la opción por la práctica liberal y 3) las implicaciones de la pandemia. Se pudo comprobar cómo los efectos de la pandemia estaban siendo vividos de forma peculiar por cada uno de los participantes y les hacía replantearse, en algunos casos, el significado del trabajo en sus vidas.

Palabras clave: psicología del trabajo; profesionales de la salud; fenomenología; pandemia de COVID-19

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) decreed that the outbreak of the disease caused by the Sars-Cov2 virus, thereupon called COVID-19, was an international public health emergency. Soon after, on March 11, its dissemination was classified as a pandemic. As a result, all countries began to adopt social distancing measures and restrictions to mitigate the spread of the disease. Control and prevention measures in Brazil were characterized by regulations directed by the federal government and carried out by mayors and governors according to the needs of each state. In the state of São Paulo, social distancing measures were adopted in March, as well as restrictions on services considered non-essential, schools, and public places, significantly impacting the current functioning of the social, educational, and labour fields, given the fact that at the time there were no vaccines to fight the virus.

Due to this sudden change, new ways of working had to be quickly adopted, including remote work. Although this way of work had been widespread and encouraged in several countries for some time, both by work-related organizations (Gaitskell, 2005) and by some universities (University of Strathclyde, 2012), until then it was only done by a few professionals.

In Brazil, remote work was adopted recently, primarily by information technology companies and multinationals. The on-site practice of many professions, such as health professions, had to be adapted to a new form of contact with the client or patient, that is, the remote form, having implications and challenges that had not been faced by these professionals until then. This is causing a migration of work to the internet and virtual environments, accelerating a process that was already taking place (Kniffin et al., 2021).

Medical care was one of the main examples in this regard, with a large-scale increase in the practice of telemedicine throughout the world, proving to be a feasible resource and initially possible to be adopted in situations such as the pandemic (Hong et al., 2020; Loeb et al., 2020). In Brazil, this resource has also been explored by several public and private institutions, with positive results both as a way of communicating with the population for preventive action, as well as in the detection of symptoms related to COVID-19 and in providing care for health conditions (Binda Filho & Zaganelli, 2020; Campos et al., 2020; Ohannessian et al., 2020).

In addition to medicine, other health sectors have also demonstrated that it is possible to act remotely, despite the limitations imposed by this type of health care. A recent article from the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul reports on the experience of remote speech therapy with 12 patients of different ages, and concludes that this type of care holds the same efficiency and quality as face-to-face care, thus being a possible way of practicing this profession when there is difficulty in accessing treatment centers (Dimer et al., 2020).

Although dental professionals’ practice requires direct contact with patients, the advent of teledentistry has been considered effective in providing preventive guidance to patients, leading clinical decision-making discussions, and increasing learning through contact with educational institutions (Carrer et al., 2020).

Nursing and pharmacy professionals have also experienced telehealth. In these fields, the aspects identified as beneficial are the possibility of reaching out to a bigger target audience (especially from the public sector), allowing nurses a quicker and easier access to monitoring, pre-clinical evaluation, and care support, as well as the help it entails for pharmacists when it comes to adequate medication control, dispensation, and guidance for patients (Balzer et al., 2020).

In the psychological field, professionals of different orientations have recognized the value of online care practices. Amador Sánchez et al. (2021) noted the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy delivered remotely for depression treatment of patients during the pandemic. Furthermore, Machado et al. (2020) also state that, despite some exceptions, psychodynamic psychotherapy delivered remotely can have effects very similar to those of a face-to-face setting.

Therefore, the present study sought to understand the experiences of health professionals in a particular context such as the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as how they found meaning in their work.

Method

The present study is qualitative and exploratory, mainly based on Edmund Husserl's phenomenology (1954/2012). This method is based on the observation of a phenomenon through its most essential features as experienced from one person’s point of view. According to Fadda and Cury (2019), the phenomenological method seeks to understand how a person perceives the facts around him, that is, the meanings that arise in his/her experiences. Focusing on the subjective aspects of a given phenomenon allows us to reflect on its structural features and reach its essence by eliminating or reducing prejudice and preconception about an event (Bezerra & Cury, 2020).

Comprehensive narratives (Brisola et al., 2017) were used as a resource of this research method. This strategy is based on empathic conversations with the participants, which guarantees genuine attention to the experience during the meeting. Consequently, meanings are elaborated together, in the intersubjective space facilitated by active and comprehensive listening. This chosen method, as well as its intervention approach, is aligned with the foundations of humanistic psychology, which seeks an authentic encounter with the participants in this research, fully respecting their point of view and speech, while delving into those aspects of the phenomenon that unfold throughout the time shared by the participant and the researcher (Fadda & Cury, 2019).

Procedure

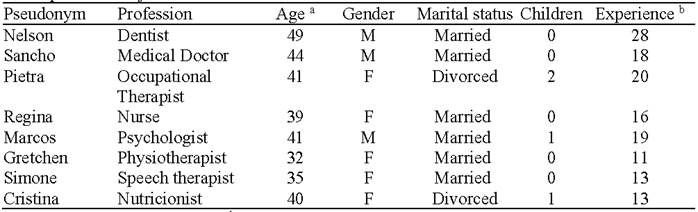

This research focused on liberal professionals from different sectors of the health area with at least 10 years of experience. A total number of 10 people were contacted and 8 participated in the meetings held by the researchers (Table 1). The aim was to delve into the meaning of work for these professionals in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study is part of a project aimed at discussing the sense and meaning of work, approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Beings (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa com Seres Humanos) from the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas and conducted by the group Psychology and Work: Experiential Approach (Psicologia e Trabalho: Abordagem Experiencial).

Most participants were selected from the researchers' contact network. Only on one occasion was the snowball technique used, when a participant was asked to refer another professional from her network, whose profile matched the one sought by the researchers. This technique consists of obtaining a chain-referral and non-probabilistic sampling, whereby the existing subjects recruit future subjects, thus increasing the sample size (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). Initial contact was made for a prior explanation about the research and invitation to participate. Subsequently, the informed consent form was sent by e-mail and after it was returned with due consent, the first meeting was scheduled online due to social distancing. On that occasion, a dialogue was fostered based on the guiding question “What is the meaning of work for you?”.

In total, 16 (sixteen) individual meetings were held, 2 (two) with each participant, through online platforms such as Zoom Meetings, Google Meet, WhatsApp, and Skype. A narrative was created by the researchers, based on the meetings held with each participant and seeking to capture their meanings and perceptions. After the narratives were validated by the research group for bias control, the researchers held a second meeting with each participant, who was invited to reread their narrative aloud, to reinforce the information captured and for further bias control. The participants could make any changes they deemed necessary, thus also obtaining their validation of the account. The next step consisted in preparing a narrative synthesis, seeking to condense the main significant elements of all the individual narratives as well as what had been discussed with the research group.

Results and Discussion

The researchers individually read and reread the narrative synthesis repeatedly, seeking to identify the significant cores, that is, the structure of the phenomenon beyond the merely expressed content. Afterward, they met to compare their observations, and as a result three structuring axes were identified.

The meaning of work for the healthcare professionals

In general, the participants believe that the meaning of the work they carry out is related to the help and improvement in the quality of life they can provide to people. On a more personal level, some held on to the ideal they had always had, while others reconsidered the meaning as they developed professionally and questioned idealizations. Despite experiencing several difficulties throughout their professional career (ranging from financial difficulties to situations of danger and life risk), they reported enjoying what they do, and some pointed out that they did not see themselves working in a different area.

After a study that included 8 countries carried out between 1981 and 1983, the Meaning of Work International Research Team (MOW) grouped the empirical data related to the meaning of work in 3 dimensions: centrality, societal norms, and work values. These dimensions are briefly characterized as (1) the centrality of work related to the level of importance that work has in a person’s life; (2) societal norms related to ethical and moral issues both of individuals and society, with their rights and duties; (3) valued results related to the motivations and purposes that work has for a person (Tolfo & Piccinini, 2007). When it comes to healthcare professionals, these dimensions are significantly expressed in their professional practice.

The centrality of work, as an element of great significance in work performance, was observed in a study with health professionals from intensive care units, who reported that the importance of their performance was on top of their financial income (Baasch & Laner, 2011). The centrality of work has often been considered a complex phenomenon (Mejía Reyes & Artiles, 2018) as it is not only linked to its results, but it also has great importance in social identity, as it also makes part of a person as a group member.

Likewise, engagement at work was directly related to the motivation and purpose of these professionals. Probably because they tend to focus on others, they point out their role in promoting the health and well-being of those who need through a holistic view of each person as such, with their sufferings, past experiences, and future perspectives (Röing et al., 2018). This fact strongly contrasts with the trend towards greater individualism and economic orientation observed in current generations by Sharabi et al. (2019).

Liberal practice as an option

Consolidating as self-employed professionals is a long and time-consuming process that requires a lot of effort for many. Previous work experiences as employees in organizations are considered important in building up what they currently do. This may be related to the acquisition of relevant skills, yet without the autonomy they would like to have to carry out what they consider ideal. The conflict between workers’ needs and organizational demands is widely discussed in studies regarding work-related diseases. These conflicts reveal a lack of balance in various aspects, either in discontent due to unmet needs linked to the meaning of work, or as a result of excessive demands, among other factors, causing harm to workers who consequently become ill (Moreira Cardoso, 2015).

Owning a business also appeared as an alternative to provide better childcare. Once their role as independent practitioners was assumed, they found out that they had to deal with administrative aspects unrelated to their professional education. In other words, they must deal with the entrepreneurial activities of those who own a business. Though aware that it is something necessary, some discomfort is expressed due to the fact that it is not within their main competencies.

While this situation brings about a conflict in terms of professional identity, it is also linked to work values, the third dimension described by the MOW group (Tolfo & Piccinini, 2007). Therefore, additional training had to be sought, as well as advice from specialized professionals and the creation of a significant network of contacts, which is essential for independent practice.

According to Różański et al. (2020) both the centrality of work and the primary importance of the family have remained unchanged and are relevant over the last decade. However, the value placed on flexible and more convenient working hours has increased. These data resonate with the experiences described by the participants of this study.

Most of them express a sense of accomplishment mainly due to the results observed with the treated patients, although some also highlight the increase in their wealth and the improvement of their living conditions as sources of satisfaction. Healthcare professions are known for being intensely demanding, both physically and emotionally. Excessive working hours, jobs in more than one location, continuous contact with human suffering, stress, as well as interpersonal and organizational conflicts in the work environment are some of the stressors pointed out, especially for those who work in public services. In this sense, independent practice can be beneficial in terms of avoiding such stressors, in addition to allowing greater freedom and autonomy in decision-making, and enabling control in the management of hours dedicated to work and personal life (Oliniski & Lacerda, 2004).

The pandemic’s implications

Each of these professionals was affected by the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, mostly due to the type of work that they do and the technical conditions necessary to carry it out. Among the most common first reactions, fear can be highlighted as one of the most prevalent, to a greater or lesser extent. Brooks et al. (2020) point out that these professionals deserve special attention under such circumstances, due to the stigmas and negative aspects that affected the health sector and consequently influenced the way these occupations were viewed at this time.

Though used to working in inhospitable conditions, the psychiatrist’s biggest fear was to infect his wife when he returned home. This same aspect is mentioned in the study by Enumo et al. (2020), which indicates that the fear of contracting a disease is one of the main stressors for these professionals, including the fear of transmission to loved ones. The dentist even thought that his profession would be doomed, since it is not possible to work remotely. Wu et al. (2020) also discussed the dilemmas that have become part of the life of independent and academic dental professionals, the impacts, and ways to reduce the risks for professionals and patients. In Brazil, the Associação Paulista de Cirurgiões-Dentistas drafted an article to guide the practice of professionals in the field, thus protecting both professionals and their patients (Franco et al., 2020).

Faced with the threat of financial loss, the nurse and the nutritionist sought employment in institutions again. Research shows that one of the factors of the pandemic that emerged as a worrying stressor is the economic difficulty that can affect people in the current period, which can cause psychological disorders and emotional changes such as anxiety and anger (Brooks et al., 2020).

Over time, the real impacts became more evident. Appointments for the nutritionist and speech therapist were drastically reduced, depending on the type of health care and collective agreement. Although the dentist and the occupational therapist suffered financial losses, they found ways to continue working by reinforcing the attention to biosafety practices, following their professional councils’ guidelines, and reducing the volume of appointments. These circumstances, as well as others previously mentioned, seem to differ from those of public health professionals, who see constantly increasing demands for care, leading to exhaustion and stressful situations (Brooks et al., 2020; Enumo et al., 2020; Faro et al., 2020).

On the other hand, although the nurse continued to see patients face-to-face, she had to use resources such as WhatsApp to respond to the growing demand for remote care. The use of technology and its advances have supported health professionals during the pandemic, transforming the way they relate to events. Certain ways of providing health care that didn’t use to be widely accepted began to be implemented in several contexts, including the private sector (Oliveira et al., 2020).

Some ambiguous situations were also observed. The psychologist had to dismiss an employee of his private practice due to the interruption of study groups and with the aggravating factor of having recently taken out a bank loan to make workspace improvements. On the other hand, he continued to see practically all his patients, and, like the psychiatrist, he observed an increase in the demand due to the mental suffering to which the population was being exposed. Several studies have described an increase in cases of mental disorders in the general population due to the pandemic, among which cases of anxiety and depression stand out (Faro et al., 2020; Lima et al., 2020).

To balance finances, the physiotherapist had to leave the premises that she rented and move to a smaller place, despite maintaining the most physically exhausting activity for her. This is in line with the problem-focused coping strategies described by Gerhold (2020) and the search for personal resources as a way to face the stresses generated by this unprecedented situation (Enumo et al., 2020). The decrease in revenue, as well as the fear of future financial losses, can also be observed in other studies that address the issue of liberal work in private practices, which were closed in some countries and/or sought financial support to continue in activity (Ferneini, 2020; Rubin, 2020).

Such experiences made some of the participants rethink their values and beliefs. Crisis periods lead people to reflect, seeking to update their coping responses, in order to act resiliently in the face of new demands. These periods also involve personal identity transformation instances, as people’s narratives about themselves change (White & Epston, 1993).

At this point, two components of identity development are lost: distinctiveness and continuity (Van Doeselaar et al., 2018). In this case, they realized that they could live without working so much and that perhaps financial factors were not so crucial. There was a reaffirmation of what is considered essential, especially to personal life, as well as an acknowledgement of a general state of tiredness due to the previous rhythm, which could only be perceived as a result of the forced pause. These families were able to find adaptive processes that allowed them to stay together, amid a context in which many relationships deteriorated (Pietromonaco & Overall, 2022).

It is worth remembering the time interval of about a month between the first and second meeting with each participant. In this regard, the researchers observed an increased apprehension of those who had thought that the pandemic would not last long and that activities would soon return to normal. In contrast, the nutritionist seemed quite excited and hopeful, as she believed that there would be a great demand for her services after this period in which people’s eating habits were disrupted. The rest, on the contrary, seemed less anxious. Uncertainty about the future was another observed phenomenon in some research studies, which marked the impossibility of future prevention as an observed aspect (Brooks et al., 2020; Enumo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

Considering both present and future issues related to the pandemic, some participants seemed to experience an imbalance between very high demands (physical, social, psychological) and low resources to deal with the unprecedented context. However, others showed the ability to deal with the situation by looking for alternatives in their environment and reviewing their way of thinking in the face of the COVID-19 phenomenon. In these cases, it is possible to observe the presence of psychological and organizational resources to deal with the tensions arising from their current work realities. Bakker and Demerouti (2007) argue that although every situation entails demands and risks, a balance between the demanding situations and the resources to deal with them can help to better cope with circumstances and improve the life quality at work.

Final Considerations

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the experiences and meanings that health professionals attributed to their work during the COVID-19 pandemic. The way professionals see their jobs is strongly related to their quality of life at work, decision-making process, and protective factors against exhaustion. Therefore, this study offers qualitative elements that allow going in-depth in these matters, considering a group of self-employed workers in a very adverse and peculiar context.

It was possible to verify that, for them, working in the health area implies taking care of the other first, an ideal that confers fulfilment and makes them overcome obstacles. Autonomy and freedom are the results of a process that required the development of administrative skills that are not part of their technical training, but necessary for the sustainability of their professional performance. The advent of the pandemic brought new challenges and the opportunity to rethink values and priorities in life. Their experiences show achievements, exhaustion, stress, hope, resilience, and flexibility.

The present study, which used a qualitative design, has some limitations. To begin with, the number of participants does not allow a generalization of the results presented, since they do not come from statistical samples of the population. Likewise, the experiences portrayed may be subject to factors that have not been mentioned, such as religious values and beliefs, family history, or political convictions. However, we believe that these would have been addressed had they been relevant. It is understood that they would have been mentioned if they had been important, or at least they would have arisen in some way in the engagement with the researchers, thanks to the openness allowed by the methodological approach based on the empathic relationship developed.

Finally, future research could extend the current findings through different strategies, such as making use of the same approach undertaken in this study to address the lives of other kinds of liberal professionals during the pandemic. The same eight categories of professionals in the present work can be analysed through other qualitative approaches and different theoretical perspectives. Quantitative studies can explore objective elements related to the performance of these professionals during the pandemic, by evaluating levels of stress, burnout, locus of control, or conditions of demands and resources based on the JD-R model, among others, offering interesting counterpoints to the results presented.

REFERENCES

Amador Sánchez, O. A., Trejos-Gil, C. A., Castro-Escobar, H. Y., & Angulo, E. J. (2021). Psicoterapia online en tiempos de pandemia: Intervención cognitivo- conductual en pacientes colombianos con depresión. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, XXVII(Especial 4), 49-60. [ Links ]

Baasch, D. & Laner, A. dos S. (2011). Os significados do trabalho em unidades de terapia intensiva de dois hospitais brasileiros. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 16(1), 1097-1105. [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309-328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115 [ Links ]

Balzer, E. R., Maria, P., Panazzolo, K., Gabriele, F., Barbosa, T., & Luiza, C. (2020). Novas Perspectivas para as Profissões de Enfermagem e Farmácia na Telessaúde. Revista Aproximação, 2(4), 29-32. [ Links ]

Bezerra, M. C. S. & Cury, V. E. (2020). A experiência de psicólogos em um programa de residência multiprofissional em saúde. Psicologia USP, 31, e190079. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6564e190079 [ Links ]

Biernacki, P. & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball Sampling Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2), 141-163. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483365817.n1278 [ Links ]

Binda Filho, D. L. & Zaganelli, M. (2020). Telemedicina Em Tempos De Pandemia: Serviços Remotos De Atenção À Saúde No Contexto Da Covid-19. Revista Multidisciplinar Humanidades e Tecnologias, 25. [ Links ]

Brisola, E., Cury, V. E., & Davidson, L. (2017). Building comprehensive narratives from dialogical encounters : A path in search of meanings. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 34(4), 467-475. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752017000400003 [ Links ]

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: a rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [ Links ]

Campos, B. H. de, Alfieri, D. F., Bueno, E. B. T., Kerbauy, G., & Ferreira, N. M. de A. (2020). Telessaúde e Telemedicina: Uma Ação de Extensão durante a Pandemia. Revista Aproximação, 2(4), 24-28. [ Links ]

Carrer, F. C. de A., Matuck, B., Lucena, E. H. G. de, Martins, F. C., Junior, G. A. P., Galante, M. L., Tricoli, M. F. de M., & Macedo, M. C. S. (2020). Teleodontologia e SUS: uma importante ferramenta para a retomada da Atenção Primária à Saúde no contexto da pandemia de COVID-19. Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada. https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.837 [ Links ]

Dimer, N. A., Canto-Soares, N. do, Santos-Teixeira, L. Dos, & Goulart, B. N. G. de. (2020). Pandemia do COVID-19 e implementação de telefonoaudiologia para pacientes em domicílio: relato de experiência. CoDAS, 32(3), e20200144. https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/20192020144 [ Links ]

Enumo, S. R. F., Weide, J. N., Vicentini, E. C. C., De Araujo, M. F., & Machado, W. de L. (2020). Coping with stress in times of pandemic: A booklet proposal. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202037e200065 [ Links ]

Fadda, G. M. & Cury, V. E. (2019). A Experiência de Mães e Pais no Relacionamento com o Filho Diagnosticado com Autismo. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 35(spe), e35nspe2. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e35nspe2 [ Links ]

Faro, A., Bahiano, M. de A., Nakano, T. de C., Reis, C., Silva, B. F. P. da, & Vitti, L. S. (2020). COVID-19 e saúde mental: a emergência do cuidado. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202037e200074 [ Links ]

Ferneini, E. M. (2020). The Financial Impact of COVID-19 on Our Practice. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 78(7), 1047-1048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2020.03.045 [ Links ]

Franco, J. B., Camargo, A. R. de, & Perres, M. P. S. de M. (2020). Cuidados Odontológicos na era do COVID-19: recomendações para procedimentos odontológicos e profissionais. Revista da Associação Paulista de Cirurgiões Dentistas, 74(1), 18-21. [ Links ]

Gaitskell, V. (2005). Working from home. Canadian Printer, 113(6), 62. [ Links ]

Gerhold, L. (2020). COVID-19 : Risk perception and Coping strategies. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xmpk4 [ Links ]

Hong, Z., Li, N., Li, D., Li, J., Li, B., Xiong, W., Lu, L., Li, W., & Zhou, D. (2020). Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences From Western China. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), e19577. https://doi.org/10.2196/19577 [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (2012). A crise das ciências europeias e a fenomenologia transcendental: uma introdução à filosofia fenomenológica. (D. F. Ferrer, Trad.). Forense. (Original work published in 1954). [ Links ]

Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., … & Vugt, M. V. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716 [ Links ]

Lima, C. K. T., Carvalho, P. M. de M., Lima, I. de A. A. S., Nunes, J. V. A. de O., Saraiva, J. S., de Souza, R. I., da Silva, C. G. L., & Neto, M. L. R. (2020). The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Research, 287, 112915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915 [ Links ]

Loeb, A. E., Rao, S. S., Ficke, J. R., Morris, C. D., Riley, L. H., & Levin, A. S. (2020). Departmental Experience and Lessons Learned With Accelerated Introduction of Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Crisis. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 28(11), e469-e476. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00380 [ Links ]

Machado, L. F, Feijó, L. P., & Serralta, F. B (2020). Prática da psicoterapia online por terapeutas psicodinâmicos. Psico, 51(3), e36529. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2020.3.36529 [ Links ]

Mejía Reyes, C. & Artiles, A. M. (2018). La centralidad del trabajo en Estados Unidos de América. Una exploración transversal 1995-2014. Sociedad y economía, (34), 185-209. [ Links ]

Moreira Cardoso, A. C. (2015). O trabalho como determinante do processo saúde-doença. Tempo Social, 27(1), 73-93. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-207020150110 [ Links ]

Ohannessian, R., Duong, T. A., & Odone, A. (2020). Global Telemedicine Implementation and Integration Within Health Systems to Fight the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call to Action. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e18810. https://doi.org/10.2196/18810 [ Links ]

Oliniski, S. R. & Lacerda, M. R. (2004). As Diferentes Faces Do Ambiente De Trabalho Em Saúde. Cogitare Enfermagem, 9(2), 43-52. https://doi.org/10.5380/ce.v9i2.1715 [ Links ]

Oliveira, W. A., de Oliveira-Cardoso, É. A., Da Silva, J. L., & Dos Santos, M. A. (2020). Psychological and occupational impacts of the recent successive pandemic waves on health workers: An integrative review and lessons learned. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202037e200066 [ Links ]

Pietromonaco, P. R. & Overall, N. C. (2022). Implications of social isolation, separation, and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic for couples’ relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 189-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.014 [ Links ]

Röing, M., Holmström, I. K., & Larsson, J. (2018). A Metasynthesis of Phenomenographic Articles on Understandings of Work Among Healthcare Professionals. Qualitative Health Research, 28(2), 273-291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317719433 [ Links ]

Różański, A., Ardichvili, A. & Byun, SW. (2020). Diez años después: cambios en el significado del trabajo entre los directivos polacos. European Journal of Training and Development, 44(8/9), 783-803. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-01-2020-0010 [ Links ]

Rubin, R. (2020). COVID-19’s crushing effects on medical practices, some of which might not survive. Journal of the American Medical Association, 324(4), 321-323. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.11254 [ Links ]

Sharabi, M., Polin, B., & Yanay-Ventura, G. (2019). The effect of social and economic transitions on the meaning of work. Employee Relations, 41(4), 724-739. https://doi.org/10.1108/er-04-2018-0111 [ Links ]

Tolfo, S. da R. & Piccinini, V. (2007). Sentidos e significados do trabalho: Explorando conceitos, variáveis e estudos empíricos brasileiros. Psicologia e Sociedade, 19 (spec), 38-46. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-71822007000400007 [ Links ]

University of Strathclyde. (2012). Homeworking: Guidelines for Homeworking. https://www.strath.ac.uk/professionalservices/media/ps/humanresources/policies/Guidelines_for_Home_Working.pdf [ Links ]

Van Doeselaar, L., Becht, A.I., Klimstra, T.A, Meeus, W.H. (2018). A Review and Integration of Three Key Components of Identity Development: Distinctiveness, Coherence, and Continuity. European Psychologist, 23(4), 278-288. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000334 [ Links ]

White, M. & Epston, D. (1993). Medios narrativos para fines terapéuticos. Paidós. [ Links ]

Wu, K. Y., Wu, D. T., Nguyen, T. T., & Tran, S. D. (2020). COVID‐19’s impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral Diseases, April, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13444 [ Links ]

How to cite: Messias, J. C. C., Borgonovi Silva Barbi, K., Tedeschi, E. H., & Labarthe-Carrara, J. (2022). The work of liberal health professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(1), e-2364. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i1.2364

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. J. C. C. M. has contributed in a, c, d, e; K. B. S. B. in b, c, d, e; E. H. T.in b, c, d, e; J. L-C. in c, d, e.

Received: December 07, 2020; Accepted: December 13, 2021

texto en

texto en