Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.2 Montevideo dez. 2021 Epub 01-Dez-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2238

Original Articles

Children on the web: perceptions of parents of children on Internet use

1 Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Brazil

2 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil, fabio.scorsolini@usp.br

This study aimed to understand the perceptions and experiences of parents of Brazilian children from nine to eleven years old regarding Internet use by their children. This is a qualitative study in which twelve genitors aged from 35 to 52 years participated, with the average age of their children being 10.16 years. Two interview scripts were employed. There was no consensus among the parents regarding how to mediate Internet use by their children, nor whether or not their privacy must be preserved in this process. However, they seem to converge regarding the concerns with the time their children spend online. Communication was made evident as an indispensable instrument for digital education. The lack of obedience to the rules imposed by the parents and the absence of parameters to mark such mediations stand out as the most significant challenges.

Keywords: parenting; Internet; parent-child relationships

Este estudo teve por objetivo compreender quais as percepções e experiências de pais e mães de crianças brasileiras de 9 a 11 anos acerca do uso da internet por parte dos seus filhos. Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo do qual participaram 12 genitores com idades entre 35 a 52 anos, sendo de 10,16 anos a média de idade dos seus filhos. Foram empregados dois roteiros de entrevistas. Não houve um consenso entre os pais a respeito de como mediar o uso de internet dos filhos, bem como se suas privacidades devem ser preservadas ou não nesse processo. Porém, parecem convergir quanto às preocupações com o tempo que os filhos ficam conectados. A comunicação foi evidenciada como instrumento imprescindível para a educação digital. Destaca-se como maiores desafios a falta de obediência às regras impostas pelos pais e a ausência de parâmetros para balizar essas mediações.

Palavras-chave: parentalidade; internet; relações pai-criança

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo comprender las percepciones y experiencias de los padres de niños brasileños de 9 a 11 años sobre el uso de internet por parte de sus hijos. Se trata de un estudio cualitativo que involucró a 12 padres de 35 a 52 años de edad y 10.16 años de edad promedio de sus hijos. Se emplearon dos guiones de entrevistas. No hubo consenso entre los padres sobre cómo mediar en el uso de internet de los niños, así como si su privacidad debe conservarse o no en este proceso. Sin embargo, parecen converger las preocupaciones sobre el tiempo en que los niños están conectados. La comunicación se destacó como una herramienta indispensable para la educación digital. Se destaca como los mayores desafíos la falta de obediencia a las reglas impuestas por los padres y la falta de parámetros para marcar estas mediaciones.

Palabras clave: parentalidad; internet; relaciones entre padres e hijos

With the increase in technological devices connectable to the Internet, the access to World Wide Web has had significant growth since its popularization in the 1990s (Terres-Trindade & Mosmann, 2016). In this context, the dissemination of Digital Information and Communication Technology (DICT), especially the Internet, has brought with it multiple opportunities and challenges in both the individual and social levels, insofar as it provided new ways for people to get to know and relate to each other (Carochinho & Lopes, 2016; Núcleo de Informação e Coordenação do Ponto BR (NICBR), 2016; Scorsolini-Comin, 2014).

Although such circumstances create opportunities to involve people, including children, in an ever more connected world, on the other hand, they establish enormous challenges for parents and educators (Centro de Estudos sobre as Tecnologias da Informação e Comunicação (CETIC), 2017). Research has pointed out that children access the Internet from an early age. In 2016, about eight in every ten (82 %) Brazilian children and adolescents aged from nine to seventeen years old were Internet users, which corresponded to 24.3 million users in the country, with around seven in every ten (69 %) children and adolescents who were Internet users using it safely, according to statements from their parents or guardians (CETIC, 2017).

Obviously, such data must be revisited in the near future, especially from the deflagration of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and its short, medium, and long-term repercussions. It is thought that such numbers have increased precisely due to the new interactive scenario, with global repercussions. Among the most significant transformations that directly concern the theme at hand is the use of communication and information tools and the Internet for maintaining the teaching and learning processes in the most varied education levels (distance learning, remote learning, hybrid learning), directly affecting children given that this more accentuated role of such technologies requires appropriate mediation by parents and guardians, which has been discussed in a more accelerated manner nowadays. Such discussions are also not separate from those about the role of the school, the daily school day, academic performance, and the emotional conditions of the students (Oliveira, Gomes & Barcellos, 2020; Wu, 2020).

Beyond this current scenario - of transit through the pandemic and the necessary reflection on the educational repercussions of this context -, it must be emphasized that the Internet represents a universe of positive and negative opportunities, especially for children, and, with this, it is necessary to view such reality with criticality so that we do not understand this instrument merely as something genuinely harmful to development (Coll & Monereo, 2010). Together with the modernization of means of communication came the changes in the form of social interaction, especially related to playing (Dias & Costa, 2012), more and more in sync with the new online technologies. With this, some of the justifications for Internet use consented by parents take place in the discourse that there is a lack of time to accompany the children in outdoor playing, a lack of security in public spaces, and even that knowing how to use and handle equipment related to DICT is of utmost importance for a competitive life in the future (CETIC, 2017).

Although access to the Internet has increased, parents often have little control over what their children are accessing when they are online (CETIC, 2017). However, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations (UN), 1989) informs that the responsibility for the instruction, assistance, guidance, and monitoring of children and adolescents until they reach adulthood at eighteen years old is of the parents. In this context, parental moderation of Internet use by children is indispensable because interdictions and limits are essential for the affective development of children and adolescents in pre- and post-verbal phases. We must recall that human development is something that occurs continuously from the individual and group changes within a given context (Bronfenbrenner, 2011).

Mediation is the term most used currently in the literature to designate the parental educational strategies directed towards the media (Grizólio & Scorsolini-Comin, 2020; Maidel & Vieira, 2015). In Brazil, the survey The Kids Online 2016 demonstrated that parental educational practices intended for Internet use, i.e., the mediations, oscillated from more permissive postures to disciplining and control. Besides, mediation of authoritarian nature was deemed cruel by the children because they ended up feeling disregarded as active agents of this new communication process. It was also possible to list the permissive mediations, in which the user themselves must decide for how long they will be on the Internet, and negligent mediation, in which there is a distancing of the parents relative to the children, who remain without any information about the risks of the Internet (CETIC, 2017).

Bronfenbrenner (2011) observed the phenomenon of the expansion of computers in family homes in the second half of the 20th century. To the author, the study of human behavior could only occur within a given context, criticizing investigations that aimed to understand how people related to each other and developed themselves in artificial environments, i.e., out-of-context. In the context of computers and new technologies, for example, he recommended understanding the family relationships within this interactive scenario, i.e., of an environment with the presence of such elements and in which people lived and interacted, producing development. Hence, it is not enough to know the environment in which a child or a family is placed; it is necessary to notice what goes on in this mean, its similarities and differences to other contexts, how the interactions take place, and how they repercuss in the development.

Starting from the assumption that each age range represents singularities that will require different postures from the parents for the mediation of the access to the Internet to be consistent with the demands placed, it is pressing to ask, as the guiding question of this study: how have parents been dealing with Internet access by their children from nine to eleven years old? In 2017, the ICT survey Kids Online pointed out that 70 % of parents or guardians believed that children and adolescents made safe use of the Internet in Brazil. On the other hand, 50 % of the children and adolescents who were Internet users reported that their parents or guardians know more or less or nothing about their Internet activities (CETIC, 2018). From this panorama, this study aims to understand the perceptions and experiences of parents of children from nine to eleven years old regarding Internet use by their children. Regarding the public addressed in this investigation, children, although the data collection narrated here took place in a pre-pandemic scenario, such notes may and must be appreciated from the ongoing transformations mobilized by the COVID-19 pandemic and may compose orientations to parents, guardians, teachers, and managers directly affected and considered in this new interactive and educational context.

Method

Study type and ethical considerations

This is an exploratory study supported by the qualitative research approach and based on the Bioecological Model of Human Development (Bronfenbrenner, 1996, 2011; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998), also known by the PPCT acronym: process, person, context, time. From the integration of these different vertices, the authors propose the study of human development from a systemic perspective, considering the need to not only describe the contexts in which development occurs but how the characteristics of such environments influence and are influenced by the interacting people. Under this perspective, development may be seized whenever there is a change in the environment and/or role, i.e., relative to the environments in which the people interact and/or relative to the roles they assume in such relationships, a concept that receives the name of ecological transition. In accordance with the Brazilian legislation (National Health Council Resolution No. 466 of December 12, 2012), this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro (CAAE 82380418.5.0000.5154 and Opinion No. 2.586.184).

Participants

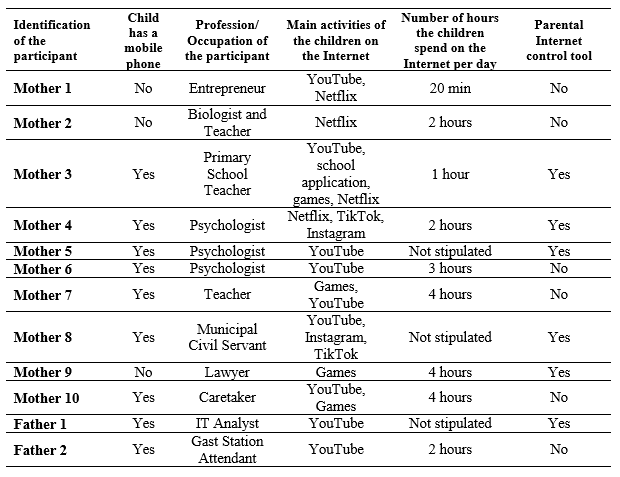

Twelve genitors (parents) with an average age of 40.33 years, varying from 35 to 52 years, participated in the study, with the average age of their children being 10.16 years. Such genitors are from a city in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The saturation criterion was employed in the sample composition, i.e., the number of participants was defined as the interviews responded to the study objectives sufficiently well and the data started repeating. The option for parents who lived with at least one child aged from nine years old to eleven years and eleven months old was because it allows a greater understanding of how family interactions take place, so to encompass the challenges of daily coexistence in the face of the parental practices. We also stress that the "child" terminology was adopted in this study to refer to those aged from nine years to eleven years and eleven months. Such a criterion is in line with the surveys The Kids Online Brazil, which have been carried out since 2012 (CETIC, 2017; 2018). Couples were not interviewed in this study, only one member of the dyad, given that the purpose was not to compare the parental experiences and practices within the same family. Table 1 presents the sample characterization.

As one may observe, most of the children (n = 9; 75 %) have their own mobile phones, concentrating their activities in the use of the YouTube and Netflix platforms, besides online games. Besides, the parents were divided regarding the issue of using instruments for monitoring the content accessed by the children, with half of the respondents using such a resource.

Instruments

The instruments used were the semistructured interview for parents of children and the structured interview, both developed by the researchers themselves. In the semistructured interview script, we addressed themes regarding the perceptions of Internet use by the children, attitudes in the face of Internet use, references used for mediating Internet access, and strategies for mediating Internet access. The structured interview script addressed more punctual questions regarding the manners and frequency of Internet use.

Procedure

Data collection

The participants were contacted from the social contacts of the researchers, being later suggested through the procedure known as snowball. The recruitment also took place through social networks such as Facebook. After selecting the participants, the terms of participation were explained, emphasizing the voluntary, confidential, and anonymous nature of the study. With these clarifications made, the participants were invited to read and sign the Free and Informed Consent Form. Later, the data collection was initiated in a reserved environment that guaranteed the privacy and material and psychological comfort of the participants. The two interviews were applied face-to-face in a single session, recorded, and later transcribed in full, composing the analytical corpus.

Data analysis

The interviews were thoroughly analyzed, highlighting, at first, the thematic axes found from the speeches of each of the respondents, i.e., a vertical analysis of the material was carried out. Second, a horizontal analysis of all the interviews was carried out, listing the points of similarities and differences among the speeches, also from the constructed thematic axes. For the qualitative analysis of the interviews, the procedures proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) were used, which aim to identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) in the obtained data, allowing the construction of thematic axes. The analysis and interpretation of the thematic axes were based on the Bioecological Model of Human Development (Bronfenbrenner, 1996, 2011; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) and the literature in the field.

Results and Discussion

From the thematic analysis, the results were grouped in four axes constructed a posteriori according to their recurrence in the reports (greater frequency of mentions) and greater signification by the participants: (a) How are the parents mediating?; (b) Changes and permanence in the quality of communication between parents and children; (c) Privacy: to have it or not to have it?; and (d) Greatest challenges.

(a) How are the parents mediating?

In this category, practices, thoughts, and rules exercised by parents with their children regarding how to use the Internet will be discussed. In advance, it is important to stress that parental educational practices are the ways parents and other guardians that assume the parental function guide the behavior of children (Silva & Pereira, 2018).

“It changed a lot, right? Nowadays, if the person doesn't want to have a hard time, they hand their mobile phone over, and the child stays the entire time with the phone at hand; if they want peace, they turn on the computer; it's easier to do this than to fight. In the past, we would give a toy; not today; nowadays, if the child doesn't want to play, we give them Internet Access” (Mother 2).

Given the excerpt presented, it is valid to understand that, in the face of the technological insertion within the family, various transformations occurred, highlighting those that curtailed the relationships among members. Although they connect people who are geographically distant, such transformations may also promote distancing between members of in-person relationships, especially regarding how we communicate due to the Internet and the new technologies. One of the striking points related to the change in communication when we think about children is the act of playing. The speech illustrated by Mother 2 marks this aspect upon revealing that, currently, playing boils down to using the Internet, a fact already pointed out by Dias and Costa (2012), who described the playing of the contemporary child as more and more in sync with new online technologies.

In the face of this scenario in which technology has been invading homes, with the permission of the parents, some health protection factors start to be reconsidered. According to the Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria (SBP, 2016), the new version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (CID-11) includes the abusive use of the technology of electronic games (the so-called gaming disorder) in the section of disorders that may cause addiction. In other words, the technological dependence on online and offline video games starts to be understood as a disorder. In this context, the role of the parents becomes even more important because they are the closest people and, therefore, those more capable of identifying in advance the symptoms stemming from the abusive use of such devices.

The literature has reported that the constant absence of parents in the daily routines of their children, albeit under the justification that there is a lack of time to accompany them in outdoor playing and a lack of security in public spaces (CETIC, 2017), may entail harm to the children. With this, nowadays, we see more and more the media such as the Internet and TV, in addition to school, dividing the space of family responsibility and socialization, previously delegated almost exclusively to the family (Levy & Jonathan, 2010; Junqueira, 2014).

Even though the role of the family in this process is being discussed constantly, mediation by the parents remains fundamental (Grizólio & Scorsolini-Comin, 2020). The way children interact on the Internet and use digital technologies often promotes, in parents, concerns regarding the risks possibly involved and even relative to the mediation necessary to regulate this use/access/frequency, as may be observed in the following speeches:

“I ask her to tell me who contacts her, who doesn't; she generally asks me: “Mom, someone like such called me”, and I say “No, block them if you don't know them”. I already taught her to block on Instagram; on WhatsApp, I taught her to block, and I talk to her” (Mother 4).

“For example, they may only play video games on weekends for two hours, so, when the video game time is up, we turn it off. There is the automatic programming; otherwise, they want to play all day” (Mother 2).

About these excerpts, it is necessary to understand that it is important for the child to receive an orientation from their parents regarding how and when to use the Internet, prioritizing the need for a routine that guides them. The child depends on their family to feel supported and, hence, needs domestic habits of reference to order their everyday life (Scholz, Scremin, Bottoli & Costa, 2015), which also spans how they relate with such technologies. As we were able to observe in the interviews, such routines and rules are defined within the family and may vary between more or less restrictive postures.

Such rules are built from particular experiences in the interaction between these subjects (parents and children) in the family microsystem but are also influenced by experiences that took place in other systems in which such people do not participate (exosystem), guided by how the macrosystem represents what such rules are, what family is, and what being a parent in this current context is (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). The systemic understanding of such vertices would allow accessing how this mediation takes place in each family, also marking orientations in the sense of establishing healthier relationships based on exchanges and dialogue.

In 2016, the Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria (SBP) launched an orientation manual for parents, children, adolescents, teachers, schools, and pediatricians. Among the suggestions present in the document, those that referenced screen time, i.e., the time that children spent using digital technology, stood out. The orientation is for this period to be limited and in accordance with the biopsychosocial development of the child, a concern made evident by the speech of Mother 2, who activates the automatic shutdown of the video game due to the need to impose a limit to this use. Besides establishing limits for the child, the effective presence of the parents in the orientation is indispensable, with there being a need to balance the hours spent online with outdoor activities, playing, exercising, or direct contact with nature (SBP, 2016).

The presence of rules that have meaning and a programmatic routine for the child is important because their development will naturally take place progressively, from a sequential process of steps throughout the life cycle, so that the developmental results that emerge at a given time are the base on which the following step is structured (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). Hence, the parents must be structuring bridges for the maturation of their children. One of the means to achieve such a proposal is mediation, enabling the developmental structuring necessary for the following phase.

The excerpt of the speech of Mother 4 points to an example of active mediation; it is an educational practice related to open conversations that aim at guidance regarding how to use the Internet safely. About this practice, it is pointed out that close communication with one's children is much more effective than strict rules regarding Internet use (Álvarez, Torres, Rodriguez, Padilla & Rodrigo, 2013).

“We have to have a measure, not to be too strict nor too permissive or liberal, because... they have to have that trust that, if something different shows up, they'll call us. Not call their friend or a classmate, but ask us” (Father 1).

“I try to see how her behavior is and assess the time because, at the same time that I work the matter of trust with her, what use will it have if I act like 24-hour police? It will be a disloyal exchange, right?” (Mother 5).

In these speech excerpts, we may clearly see the prioritization of a relationship of trust with one's children instead of implementing strict and controlling rules regarding Internet use. In this sense, we may notice that one of the main points of discussion when speaking of mediation is the quality of the communication established between parents and children. In the speech of Father 1, we observe the existence of a measure for this mediation, described by him in terms of a balance between strictness and permissiveness. However, we may problematize that this more balanced posture does not always occur in an ordered manner or without conflict. Hence, however much the parents make attempts regarding virtual education, they may often feel ambivalent in how to do so, demanding a more permanent posture of assessment relative to mediation. Therefore, there is no way to establish the same mediation model throughout the entire development of one's children.

Open communication has been pointed out as the best way when we think of risk control (CETIC, 2017). In the survey conducted by Li, Dang, Zhang, Zhang and Guo (2014), factors such as honest expression of respect and love were seen as protection instruments.

It is relevant to stress that excessive protection may limit the opportunities offered by the Internet, which could aid the growth, autonomy, responsibility, and resilience of the child. It is also important to be mindful of the environment surrounding one's children because parental mediation alone is not enough to protect and guide. Therefore, an interlocution with the school and considering peers as potential influencers are necessary (Shin & Lwin, 2017). From a bioecological perspective, we may understand that the interaction among the different systems (micro, meso, exo, and macrosystem) allows not only the construction of mediation practices but also of the perceptions of such subjects in the face of the characteristics of such environments.

(b) Changes and permanence in the quality of communication between parents and children

In this category, the parents reported some perceptions regarding the singularities of their own generations and that of their children, evincing communication and relationship difficulties with their parents. It becomes evident that, although the insertion of the Internet engendered new challenges for parents, there were also difficulties in their generations.

“I think like so, that we cannot start from a perspective that is just melancholic, of saying that, at that time, it was better, right. Because there were difficulties too, right. For example, in my relationship with my parents, eh, there was no Internet, but, affectively, it wasn't so close, and we didn't talk so openly as I talk with my daughters. (...) So I think that they are different places, different moments in history” (Mother 7).

As we may notice by the speech of Mother 7, the parental practices do not take place in a manner disconnected from the social-historical moment, highlighting the role of the macrosystem, responsible for the transmission of culture, but also of the historic time represented by the succession of generation (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). Before, the patriarchal model predominated, in which the authoritarian style caused parents to assume an unquestionable authority. With time, new forms of family consolidation emerged, with other ways to be a family. The relationships became less hierarchized and more participative (Silva & Pereira, 2018), albeit aspects considered more traditional are maintained.

The Internet occupies an important role in the changes that took place because there was a transformation of the way of communicating; the information was no longer frontal or linear of the emitter-receiver type. Now, the communication process takes place on the Internet as an ecosystem and, therefore, is subject to relationships with other ecosystems. This communication model connects people, territories, the environment, and nature (Di Felice, 2012). Hence, there was a need to adapt to and understand the new reality, a context that ended up requiring from society a resignification of the family roles (Scholz et al., 2015).

For the bioecological model, the context that surrounds us may determine our ways of handling each situation, but it also presumes a dynamism that allows us to react and produce in the face of the ecological environments of which we are part. As stated by Bronfenbrenner (1996), development takes place in a “progressive, mutual accommodation between an active human being and the mutating properties of the immediate environments in which the person lives as this process is affected by the relationships among these environments and the broader contexts in which the environments are inserted” (p. 18).

We may notice that, although the environments have changed, the communication between parents and children is still determinant when talking about education. Communication takes on a new look from the democratization of the Internet. However, when we think about the parental difficulties in dealing with the Internet, the bond that is established between parents and children seems to be more determinant than other justifications such as, for example, that the parents feel hostage to technology, or even that the world is dangerous or they have no time. Noting that the absence of protection of this public may entail permanent consequences (CETIC, 2017).

Bad experiences with educational practices of restrictive nature may promote in parents the attempt to educate their children differently from what they experienced with their own genitors. From this, the parents may be more flexible, pondering restrictions that would even be important to their children's development. In this movement, parents end up putting within reach everything their children wish for, delegating to therapists and teachers the task of educating them (Junqueira, 2014).

The lack of healthy communication within the family may harm the positive use of the Internet. The dialogue between parents and children may be a prevention strategy (Appel, Holtz, Stiglbauer & Batinic, 2012), especially considering that this is an intervention that takes place in the microsystem, i.e., in the mean in which the developing people have active participation, which promotes actions with more significant potential for change and implication on development. In the scientific literature, it is a consensus that family may be intimately related to the problems that children and adolescents may have of affective and behavioral nature (Bernal, 2012; Terres-Trindade & Mosmann, 2016). In this context, it is important to notice that among the main factors of problematic Internet use (PIU) are dysfunctional parenting styles, such as the lack of cohesion and communication (Patrão et al., 2016).

(c) Privacy: to have it or not to have it?

In this category, various viewpoints regarding the privacy that children should or should not have when accessing some Internet content will be discussed. The respondents highlighted two main positions: the first suggesting that, as parents, they must not invade the privacy of their children, respecting them, and the second that the preservation of such privacy may put their children in the face of danger.

“I think that this matter of the software is a complete invasion of privacy; I also think that such a great panic was established in society, and people want to be seeing the entire time it is happening, and it's not like that, whatever happens, will happen even if you have that software” (Mother 1).

In the excerpt of the speech of Mother 2, there is a repudiation of software for monitoring Internet use, with her expressing herself as against the insertion of monitoring of the content that the child accesses. Hence, she positions herself in defense of the privacy of children on the Internet without parental control. The programs for blocking and filtering websites either do not result in effective protection or prevent access to harmless and even educational content (Monteiro, 2008). To this author, it is worth much more to develop in the child a critical view regarding what the Internet is about so to guide and teach them how to deal with this new world, avoiding its threats but also enjoying its opportunities in the best way.

Internet use has become part of the everyday lives of families, and people must reformulate their meanings and values (Hintz, 2001). The goal is to know how to alert them to what may put their physical and psychological integrity or their educational process in check without preventing contact with this reality. Doing so would be like not allowing a child to go out on the street so that they were not in danger of being hit by a car or mugged. Nowadays, new Internet users have become an unavoidable reality, with information that allows achieving this knowledge being necessary (Monteiro, 2008).

While television generated a fuss similar to that of the Internet nowadays, at that time, the children were mere passive subjects receivers of all the uncontrollable information from TV. In turn, in the Internet age, users have the autonomy to change, stop, and repeat, opting to access content according to their tastes and preferences (Monteiro, 2008). What has been much discussed in contemporaneity is that even without ceasing the essential care that belongs to the guardians, more and more importance is given to the autonomy of the children. The child's opinion that used to be ignored became fundamental (Silva & Pereira, 2018).

“She is still very innocent, you know, like she doesn't have even a little bit of malice; I talk to her a lot, and I am worried about her with this issue of pedophilia, of abuse... so I care more about her safety than her privacy at this movement of her life; when she is a little older, the tendency is to become more relaxed gradually, but not for now” (Mother 4).

“Children can't have privacy. Like, passwords on their phones, they can't have that. Or posting on some app that has a password... doing things hidden from us or else they cannot have privacy. It's funny... the Internet is very dangerous” (Father 2).

The excerpts of the speeches of Mother 4 and Father 2 point to a recurring concern in access to the Internet by children, signaling that privacy at this age is not necessary because the priority would be protection and not autonomy. About this excerpt, it is known that the discerning ability of children to select the appropriate contents to visit on the Internet, as well as their ability to judge the safety of providing information online, must be lapidated by the parents from active parental mediation, i.e., maintain a good communication channel with one's children in the sense of offering a space of trust and guidance (Lwin, Stanaland & Miyazaki, 2008). However, dialogue alone may not be sufficiently effective for children, indicating a need for clear rules on Internet use.

Regarding the issue of surveillance and privacy, SBP (2016) pointed out that it is necessary to have a dialogue with children regarding the rules and what is safe for them to access, avoiding that there be exposure and sharing of personal information. There is an incentive for monitoring websites, programs, applications, and videos that children access. In a more technical language, the document guides the use of software or programs that work as security filters and word monitoring.

In contrast, studies point that content restriction software is more indicated for parents who are not being successful in their respective mediators, generally overly permissive or restrictive mediations. In turn, parents who use mediation that considers good communication are generally more shielded from possible personal data disclosure events and exposure on the Internet. Hence, the parenting style would be directly related to the risk that the child is at when accessing the Internet (Lwin et al., 2008).

(d) Greatest challenges

In this category, the parents report the most significant challenges when the theme in question is the education of their children in the Internet age. The most significant points of concern are concentrated on the unlimited extent of contents on the Internet, which hampers supervision, the lack of references of how and when to mediate Internet use, and the lack of obedience by the children.

“I think that we stay in a huge conflict between overprotecting and underprotecting; I think that the challenge for my generation in motherhood and fatherhood is precisely that of knowing up to when to protect and up to when to let them be, because we had experiences that protected too much and it didn't work out, and then they become adults that don't know how to do anything. (...) We keep trying to balance these two worlds, one of overprotecting that we know doesn't work and the other of a little less mediated protection” (Mother 4).

The speech of Mother 4 reports a challenge related to the mediation of the accessed contents, revealing that there is no way to establish very well delimited rules because the needs modify over time. Hence, parents are going to use various types of mediation throughout their exercise of parenting. In a study, the parents reported using, in general, active mediation through dialogue and more restrictive rules in specific situations such as, for example, when the family is having dinner or when the use of risky websites is detected. The parents deemed open communication the best way to be followed (Symons, Ponnet, Walrave & Heirman, 2017).

The parents are still trying to adapt to the new forms of behavior of their children, such as when they are surprised when their children claim to have hundreds of online friends or, yet, when they have to deal with their children's revolt with sanctions or restrictions relative to smartphone use. There is no clear understanding of what composes these new forms of relationship, nor an acceptance that they may modify themselves continuously. References are still sought in the old forms of playing, learning, and relating, even with the increase in knowledge production on digital natives (Monteiro, 2008).

Given this context, nowadays, we experience a phenomenon entitled “fragilization of parental functions”, characterized by parents who feel guilt, doubt, and insecurity relative to how they position themselves in the face of what they may, must, or must not do with their children. Hence, it is necessary to understand what historical, sociocultural, and economic determinants contribute to this current behavior of parents (Zanetti & Gomes, 2011). This disruption present in the family caused parents to start to distrust their competencies to educate their children, given that their know-how is disqualified relative to that of specialists. Hence, these authors claim that the difficulty that parents have in saying "no" is more and more present since they expect social and media to do so.

“The most significant challenge, in my opinion, is obedience. It is a huge challenge because... it ends up that children, nowadays, because they watch many movies, series, cartoons, they create a superhero for themselves. They have an image that someone is a superhero. And sometimes this image steals the role of the parent, the image of the father and the mother, get it? In the past, one would ask: what do you want to be? Oh, my dad is a mechanic. What do you want to be? I want to be a mechanic when I grow up, right. Not nowadays; the child wants to be... they no longer see the father's profession, they don't understand, they don't want to follow the father's career. They want to follow the series that they watch on television, on the Internet, those things” (Father 2).

The technological transformations made it so that, inevitably, people had to adapt, acquiring new values, forming a generation of “digital natives” that are unable to imagine life without using technology (Cartaxo, 2018). Largely responsible for such changes, the Internet impacted primarily the quickness with which information circulates (Shimazaki & Pinto, 2011), inevitably affecting the children's world.

The generational gap seems to aggravate, and the shock between adults and youths has often been excessively evident. For the youths, this is already an unavoidable relationship, whereas, in the eyes of adults, it emerges almost as an obsession or extreme dependency, especially because, in this frame, the distinction between learning and having fun is still tenuous (Monteiro, 2008). To Zanetti and Gomes (2011), in contemporaneity, small children constantly challenge the authority of their parents, presenting a much more intense behavior regarding indiscipline than children from previous generations.

In their new context, the children grow in a world that appears unknown to their parents, a world in which, according to their interests, they themselves select the type of information to assimilate, constructing their models of knowledge, growth, and sociability. The autonomy that predominated in the way younger people appropriated new technologies, the way they learned on their own to make use of such tools, surpassing the adults, gave them a sense of independence and ended up conferring them a power that they do not seem minimally willing to lose (Monteiro, 2008). Understanding how the macrosystem (history, culture, global context) presents itself in family interactions proves to be a need, especially under a developmental perspective the focus of which is systemic, which entails overcoming discussions centered on individual psychological aspects of parents and their children (Bronfenbrenner, 2011).

Lastly, it must be highlighted that the possible emerging conflicts relative to this issue of Internet use also remit to other family experiences and the management of rules and guidelines that may vary from home to home and also suffer the influence of the different generations and socioeconomic markers. Allowing the construction of the autonomy of children without them being exposed to risks seems like a challenge narrated by most of the respondents regarding Internet access, composing a pressing theme in both Developmental Psychology and parenting.

The progressive development of autonomy in children must be accompanied by changes in the way the parents respond to this process, also allowing the children to take on new roles and amplify quantitatively and qualitatively their participation in the environments in which they interact and develop. According to Bronfenbrenner (2011), this continuous process would allow ecological transitions both as evidence that development occurred/is occurring and as invitations to new learnings and maturity.

Although this study was conducted before the pandemic period, it is thought that the reflections and parental concerns relative to the mediation of Internet use by their children are still a pressing issue. It is obvious that such discussions must also be addressed in future studies already considering the transit of the pandemic and its effect, given that all members of the family began to dialogue more profoundly with the Internet and new technologies, be it through remote work (home office), remote learning, or, primarily, the more significant coexistence among the family members, and the preponderant role of the Internet and virtual relationships in this context (Lemos, Barbosa & Monzato, 2020; Soto, Moreno & Rosales, 2020; Vila, 2020). In this sense, it is important for studies such as the one presented herein to be able to follow the changes in such families during the pandemic, and they may even allow resignifications surrounding parenting, mediation, and the relationship with the Internet and new technologies.

Final Considerations

This study aimed to understand the perceptions and experiences of parents of Brazilian children from nine to eleven years old regarding Internet use by their children. With that in mind, it was possible to observe that parents have concerned themselves with their children's Internet use, implementing rules, especially about the number of hours they may access it, and providing them with a routine to be followed.

In the interviews, many parents made some reflections about the changes in family communication in the face of the insertion of the Internet in everyday life. In this regard, we may ponder about the socioeconomic and cultural reality of families and the construction of the spaces for sociability and coexistence between parents and children in the face of new markers such as the Internet, dual-career couples, the role of schools, and the virtualization of relationships, among others. Discussing the changes observed from one generation to the next may bring essential elements for us to think not only of the effects of the Internet and new technologies but of how parenting transforms itself in response to new family contexts and challenges.

There was also an interesting counterpoint among the speeches of the participants regarding Internet access privacy. While some parents vehemently stressed that they thought invading their children's privacy to control what they access and how they access it is unacceptable, others stated that children must not have privacy but rather be protected from risks by the vigilant supervision of their parents. Lastly, the parents reported the most significant challenges relative to raising their children in the Internet age. Among the factors, we may highlight the uncertainty of such parents regarding how to mediate the access, whether dialoguing or imposing restrictions. The obedience difficulty of children nowadays, who give more credit to their media idols than their parents, was also made evident.

As one could notice, there is no consensus when the theme in question involves parental educational practices intended for the mediation of Internet use by children. Since the studied phenomenon may still be considered recent, parents still feel helpless and with no references to educate their children in this regard, given that such challenges do not find resonance in their own life stories or the practices undertaken by their genitors in the past. For this reason, investigations that present the experiences of parents in this context are quite valid to compose the new references on the phenomenon.

Hence, this study enabled the discussion of perceptions of parents relative to Internet use by their children and may contribute to research on parenting, providing parameters for parents to benefit from the presented experiences. Nevertheless, the data herein cannot be generalized because they may also reflect socioeconomic elements of the respondents, besides aspects of parenting experienced in this cultural context, having the cutout of a medium-sized city in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Notwithstanding such limitations, the data signal the transition of these parents in the face of a complex phenomenon that spans parenting. This transition seems to be a group phenomenon in contemporaneity. If in the past new technologies did not emerge as an issue that mediated the relationship between parents and children, nowadays, they present as an element that composes the way such people, in family, interact, communicate, and produce practices of education and care.

Moreover, this reflection becomes even more pressing if we consider the recent modifications promoted by the COVID-19 pandemic of global reach. In this new interactive context, this mediation has become more and more important, as proven by the important markers such as the continuity of the remote teaching and learning processes, the more time children spend at home with their parents, and a need for a new family organization so that children keep being schooled and parents continue their work processes. The discussions about the socioeconomic markers of this period could and should also come to the table in future investigations, allowing new considerations about mediation.

There is a need for studies that carry out an interlocution with schools so to enable drawing a parallel between the main demands and needs of teachers and parents, broadening the intelligibility on the matter. Comparative studies on educational practices adopted by parents may also contribute to the theme, as well as studies exploiting families with divorced couples or even with children who live with only one of the genitors, allowing the collation of different mediation practices that affect the same child and their reflections on the development.

Deepening the dialogue with the bioecological model may be a guiding aspect in the sense of dealing with the complexity that involves the theme. In this model, the contexts are not static but precisely dynamic, allowing an apprehension of the process and the developmental changes. From the pandemic, for example, it is thought that parental mediation may have become more present in the family context given the emergency of remote and hybrid learning. Investigating this process is a recommendation for future studies.

Relative to the implications to the practice, this study revealed that the way parents have carried out the mediation of Internet use together with their children is permeated by doubts and may generate conflicts relative to the exercise of parenting and the future consequences of such mediation. We highlight that such models must dialogue with each context, keeping in mind the elements that span the understanding of the family system. From the bioecological model, we may emphasize the need for collating the four vertices - person, process, context, and time - in an articulated manner. This involves implicating more scenarios in this relationship beyond the family, such as school and the interactions established on the Internet in a dynamic manner deeply marked by the pandemic. This systemic perspective may be useful to reflections and clinical and educational interventions that surpass the focus on particular psychological aspects of each family, prioritizing the complex integration of the vertices in promoting development.

REFERENCES

Álvarez, M., Torres, A. E., Rodríguez, E., Padilla, S., & Rodrigo, M. J. (2013). Attitudes and parenting dimensions in parents’ regulation of Internet use by primary and secondary school children. Computers & Education, 67, 69-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.03.005 [ Links ]

Appel, M., Holtz, P., Stiglbauer, B., & Batinic, B. (2012). Parents as a resource: Communication quality affects the relationship between adolescents’ Internet use and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1641-1648. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.08.003 [ Links ]

Bernal, A. C. L. (2012). Funcionamiento familiar, conflictos con los padres y satisfacción con la vida de familia en adolescentes bachilleres. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 15(1), 77-85. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. Em W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Orgs.), Handbook of child psychology Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 993-1028). New York: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1996). A ecologia do desenvolvimento humano: experimentos naturais e planejados. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2011). Bioecologia do desenvolvimento humano: tornando os seres humanos mais humanos (A. Carvalho-Barreto, trad.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Carochinho, J. A. B., & Lopes, M. I. (2016). A dependência à Internet nos jovens de uma escola de cariz militar. Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente, 7(1), 489-507. [ Links ]

Cartaxo, V. (2018). Eu, minha família e a tecnologia. Revista Psique: uma multidão de solitários, 82(148), 44-51. [ Links ]

Centro de Estudos sobre as Tecnologias da Informação e Comunicação (CETIC). (2017). Pesquisa TIC Kids On-line Brasil. Recuperado de http://cetic.br/publicacao/pesquisa-sobre-o-uso-da-internet-por-criancas-e-adolescentes-no-brasil-tic-kids-online-brasil-2016/ [ Links ]

Centro de Estudos sobre as Tecnologias da Informação e Comunicação (CETIC). (2018). Pesquisa TIC Kids Online Brasil. Recuperado de https://www.cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/tic_kids_online_2017_livro_eletronico.pdf [ Links ]

Coll, C. & Monereo, C. (2010). Psicologia da educação virtual: aprender e ensinar com as tecnologias da informação e da comunicação. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Di Felice, M. (2012). Redes sociais digitais, epistemologias reticulares e a crise do antropomorfismo social. Revista USP, 92(1), 6-19. doi: https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9036.v0i92p6-19 [ Links ]

Dias, D. R. & Costa, A. M. N. (2012). O brincar e a realidade virtual. Cadernos de Psicanálise, 34(26), 85-101. [ Links ]

Grizólio, T. C. & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2020). How has parental mediation guided Internet use by children and adolescents? Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 24, e217310. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-35392020217310 [ Links ]

Hintz, H. C. (2001). Novos tempos, novas famílias? Da modernidade à pós-modernidade. Pensando Famílias, 3(1), 8-19. [ Links ]

Junqueira, M. F. A. (2014). Parentalidade contemporânea: encontros e desencontros. Primórdios, 3(3), 33-44. [ Links ]

Lemos, A. H. C., Barbosa, A. O., & Monzato, P. P. (2020). Mulheres em home-office durante a pandemia da COVID-19 e as configurações do conflito trabalho-família. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 60(6), 388-399. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020200603 [ Links ]

Levy, L., & Jonathan, E. G. (2010). Minha família é legal? A família no imaginário infantil. Estudos de Psicologia, 27(1), 49-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2010000100006 [ Links ]

Li, C., Dang, J., Zhang, X., Zhang, Q., & Guo, J. (2014). Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: The effect of parental behavior and self-control. Computers in Human Behavior, 41(1), 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.001 [ Links ]

Lwin, M. O., Stanaland, A. J., & Miyazaki, A. D. (2008). Protecting children’s privacy online: how parental mediation strategies affect website safeguard effectiveness. Journal of Retailing, 84(2), 2015-2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.04.004 [ Links ]

Maidel, S. & Vieira, M. L. (2015). Mediação parental do uso da internet pelas crianças. Psicologia em Revista, 21(2), 293-313. doi: https://doi.org/10.5752/P.1678-9523.2015V21N2P292 [ Links ]

Monteiro, A. F. (2008). A internet na vida das crianças: como lidar com perigos e oportunidades. V Conferência Internacional de Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação na Educação. Recuperado de https://www.academia.edu/4537733/A_internet_na_vida_das_crian%C3%A7as_lidar_com_perigos_e_oportunidades [ Links ]

Nações Unidas. (1989). Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança. Reuperado de https://www.unicef.org/brazil/convencao-sobre-os-direitos-da-crianca [ Links ]

Núcleo de Informação e Coordenação do Ponto BR (NICBR). (2016). Um estudo de caso longitudinal sobre o uso das tecnologias de informação e comunicação em 12 escolas públicas. São Paulo: Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil. Recuperado de http://cetic.br/publicacoes/indice/estudos-setoriais/ [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. B. A., Gomes, M., & Barcellos, T. (2020). A Covid-19 e a volta às aulas: ouvindo as evidências. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 28(108), 555-578. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-40362020002802885 [ Links ]

Patrão, I., Reis, J., Madeira, L., Paulino, M. C. S., Barandas, R., Sampaio, D. ... & Carmenates, S. (2016). Avaliação e intervenção terapêutica na utilização problemática da internet (UPI) em jovens: revisão da literatura. Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente, 7(1-2), 221-243. [ Links ]

Scholz, A. L. T., Scremin, A. L. X., Bottoli, C., & Costa, V. F. D. (2015). O exercício da parentalidade no contexto atual e o lugar da criança como protagonista. Estudos de Psicanálise, (44), 15-22. [ Links ]

Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2014). Psicologia da educação e as tecnologias digitais de informação e comunicação. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 18(3), 447-455. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3539/2014/0183766 [ Links ]

Shimazaki, V. K., & Pinto, M. M. M. (2011). A influência das redes sociais na rotina dos seres humanos. FaSCi-Tech, 1(5), 171-179. [ Links ]

Shin, W. & Lwin, M. O. (2017). How does “talking about the Internet with others” affect teenagers’ experience of online risks? The role of active mediation by parents, peers, and school teachers. New Media & Society, 19(7), 1109-1126. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815626612 [ Links ]

Silva, E. R., & Pereira, M. C. (2018). A criança em foco: conversando sobre práticas parentais e estratégias de negociação. Revista Psicologia em Pesquisa, 12(3), 1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.24879/2018001200300478 [ Links ]

Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria (SBP). (2016). Saúde de Crianças e Adolescentes na Era Digital. Recuperado de http://www.sbp.com.br/fileadmin/user_upload/2016/11/19166d-MOrient-Saude-Crian-e-Adolesc.pdf [ Links ]

Soto, M. A. V., Moreno, W. T. B., & Rosales, L. Y. A. (2020). La educación fuera de la escuela en época de pandemia por Covid 19. Experiencias de alumnos y padres de familia. Revista Electrónica Sobre Cuerpos Académicos y Grupos de Investigación, 7(14), 111-134. [ Links ]

Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2017). A qualitative study into parental mediation of adolescents’ Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 423-432. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.004 [ Links ]

Terres-Trindade, M., & Mosmann, C. P. (2016). Conflitos familiares e práticas educativas parentais como preditores de dependência de internet. Psico-USF, 21(3), 623-633. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712016210315 [ Links ]

Vila, N. I. D. (2020). El teletrabajo y la conciliación con el entorno de convivencia familiar durante la pandemia COVID-19. Revista de Investigacion Psicologica, (n. spe.), 68-72. [ Links ]

Wu, D. (2020). Disentangling the effects of the school year from the school day: evidence from the TIMSS Assessments. Education Finance and Policy, 15(1), 104-135. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00265 [ Links ]

Zanetti, S. A. S., & Gomes, I. C. (2011). A “fragilização das funções parentais” na família contemporânea: determinantes e consequências. Temas em Psicologia, 19(2), 491-502. [ Links ]

Correspondence: Fabio Scorsolini-Comin, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. E-mail: fabio.scorsolini@usp.br

How to cite: Grizólio, T. C. & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2021). Children on the web: perceptions of parents of children on Internet use. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(2), e-2238. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2238

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. T. C. G. has contributed in a, b, c, d; F. S-C. in a, c, d, e.

Received: August 17, 2020; Accepted: September 28, 2021

texto em

texto em