Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.2 Montevideo dez. 2021 Epub 01-Dez-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2484

Original Articles

Psychometric properties of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ) in college students from Venezuela

1Centro de Investigación y Evaluación Institucional (CIEI), Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB), Venezuela, dchaustr@ucab.edu.ve

The research had as primary objective to analyze the psychometric properties and the adequacy of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ) in a non-probability sample of college students (N = 159; 74 % women) from a private university in Caracas (Venezuela). Through a snowball procedure, the data were collected via application of an online questionnaire. Using an exploratory factor analysis, the proposed factorial solution was obtained; also, significant correlations were found between admiration and rivalry with self-esteem, extraversion, openness and agreeableness, just as stated in the literature. The NARQ presents evidence of validity and reliability, and therefore its use could be recommended in the Venezuelan population.

Keywords: narcissistic personality; narcissism; admiration; rivalry; adaptation

La investigación tuvo como objetivo analizar las propiedades psicométricas y la adecuación del Cuestionario de Admiración y Rivalidad Narcisista (NARQ) en una muestra no probabilística de estudiantes universitarios (N = 159; 74 % mujeres) de Caracas (Venezuela), pertenecientes a una universidad privada. A través del método bola de nieve se recabó la información por medio de la administración de un cuestionario en línea. Mediante el análisis factorial exploratorio se comprobó la solución factorial propuesta, también se hallaron relaciones significativas entre admiración y rivalidad con autoestima, extraversión, apertura y afabilidad, tal como se reporta en la literatura. Se concluye que el NARQ presenta evidencias de validez y confiabilidad, y por tanto se recomienda su uso en la población venezolana.

Palabras clave: personalidad narcisista; narcisismo; admiración; rivalidad; adaptación

O objetivo da pesquisa foi analisar as propriedades psicométricas e a adequação do Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ) em uma amostra não probabilística de estudantes universitários (N = 159; 74 % mulheres) de Caracas (Venezuela), pertencentes a uma universidade privada. Utilizando o método bola de neve, as informações foram coletadas por meio da aplicação de questionário online. Mediante análise fatorial exploratória, confirmou-se a solução fatorial proposta, também foram encontradas relações significativas entre admiração e rivalidade com autoestima, extroversão, franqueza e simpatia, assim como se descreve na literatura. Conclui-se que o NARQ apresenta evidências de validade e confiabilidade, portanto, seu uso é recomendado na população venezuelana.

Palavras-chave: personalidade narcisista; narcisismo; admiração; rivalidade; adaptação

Narcissism is a personality construct with a long history in psychology. In the 1980’s a series of events occurred related to research around this construct: an increase in the prevalence of narcissistic symptoms reported by psychologist and analysts (Tyler, 2007); also, the narcissistic personality was included as a personality disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 1980). From this decade emerged important innovations in the measuring process of narcissism. In addition to the clinical interview and observation, standardized self-report questionnaires began being a common practice. These have been studied and validated both in clinical and non-clinical populations (Emmons, 1987).

The systematization of these results, as a product of this new direction in narcissism research, brought new advances, especially those achieved by social and personality psychology, whose contributions allowed the verification or rejection of some of the assumptions sustained in the past derived from clinical research (Levy, Ellison & Reynoso, 2011). From this emerged a new form of understanding this heterogenous construct, whose characterization drastically changed from psychiatry, clinical psychology and social and personality psychology (Pincus & Roche, 2011), discrepancies that implied different social consequences for these traits. Conceptualizing the narcissism as a two-dimensional construct allowed to comprehend part of the reasons for the heterogeneity found in the research, given that both components shared nuclear characteristics, although their specific traits differ considerably (Wink, 1991).

In the 2010’s, new theoretical postures have emerged to contribute with more complete explanations, also including new ways of measuring narcissism. Although some widely used questionnaires already existed, as is the case of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Raskin & Hall, 1979; Raskin & Terry, 1988) and the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin & Cheek, 1997), some years ago new forms for measuring the construct appeared, in syntony with the subjacent advances in the theory (Rogoza, Zemojtel-Piotrowska & Campbell, 2019).

One of the recent theoretical postures is denominated as Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Concept (NARC; Back et al., 2013). Its underlying assumption is that all individuals, categorized as narcissists, strive for a specific goal: to maintain a grandiose vision of themselves. The ways to achieve this goal are varied, NARC model specifically propose two general strategies, denominated narcissistic rivalry and admiration, respectively.

Initially, the predilect strategy used by narcissists is the admiration. This one is characterized by the tendency to promote a positive self-image, through social admiration obtained when standing out in front of others (Back, 2018). Other characteristics consists in showing themselves as talkative and constantly pointing out their positive qualities and achievements. The results associated with this approximation tend to be positive in the short-term; however, in the long-term, recognition and liking from other people tend to decay considerably (Wurst et al., 2017).

The second strategy used is the narcissistic rivalry. This one is characterized by the tendency to protect the individual from a negative self-view through the devaluation of others, also showing selfish, socially insensible, arrogant and hostile behaviors, in conjunction with a lack of empathy, interpersonal affect and forgiveness towards others (Wurst et al., 2017). In these cases, the individual chooses to denigrate and devaluate the people that compete for status and recognition. In this way, by publicly underappreciating the qualities of others, they boost their own. This strategy, unlike admiration, usually generates negative results both in short as in long-terms (Wurst et al., 2017).

The predilection or disposition of an individual to implement one specific strategy is also a current point of discussion. It seems that some personality characteristics tilt the balance in one direction or another, some social cues of the environment and the feedback that other people give to the implementation of a specific strategy also play a part (Back, 2018).

In regard to the relevance of the personality traits in this aspect, it has been found the following relationships (Back et al., 2013; Leckelt et al., 2017): extraversion often is associated with both strategies, although in opposite directions. More extroverted individuals tend to use the admiration strategy, while the rivalry is most often negatively associated with this trait. A similar situation is present with neuroticism, however, in this case, the one strategy that presents a negative association with the trait is the admiration, while the narcissistic rivalry shows a positive correlation. Another personal characteristic that has been associated in a specific pattern with these strategies is self-esteem. Specifically, it has been found that admiration presents a positive correlation with self-esteem; whereas rivalry presents a negative correlation (Geukes et al., 2017).

In addition, other determinant factor in the implementation of one particular strategy consists in the social consequences caused by the strategy. Positive social consequences reinforce the use of the admiration strategy; in the case that the expected recognition is not achieved, the individual often shifts to others denigration through rivalry (Back, 2018). This distinction in regard to the way in which a narcissist person behaves in a social environment is crucial. Even though the underlying traits remain stable, the way in which an individual behaves to achieve the same goal, social status, may change considerably, producing different results that may affect, on one side, his permanence within a group (Benson, Jeschke, Jordan, Bruner & Arnocky, 2018), and his relationships with other people, on the other side (Wurst et al., 2017). The questionnaire, developed in consonance with the NARC model (Back et al., 2013), allows to evaluate both aspects at the same time.

The Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (Back et al., 2013) is a test developed to evaluate the elements associated with the rivalry and admiration strategies. In both cases, it also assesses the cognitive, affective and behavioral elements associated with these strategies. For this reason, it can be considered an instrument of great utility in personality assessment. This short instrument also has demonstrated adequate psychometric results in different contexts and populations (Doroszuk et al., 2019).

In this sense, the NARQ is an instrument that allows the assessment of both dimensions of narcissism, including at the same time subjacent motivations, as well as the behavioral results and the interpersonal dynamics of both (Leckelt et al., 2017). This is one of the principal advantages of the questionnaire, especially in comparison to other instruments more frequently used, such as the NPI, which has showed a scarce coverage of the more maladaptive aspects of narcissism (Leckelt et al., 2017).

Recently, multiple language adaptations have been made to the questionnaire, showing in each case adequate psychometric properties. Within these versions the following can be mentioned: a) Polish, showing adequate indicators of reliability and factorial validity, this last one observed through a confirmatory factor analysis (Rogoza, Rogoza & Wyszynska, 2016); b) Italian, where once again, via a confirmatory factor analysis, the two-factor structure was obtained, as well as the reliability and the external validity, testing the differential association with self-esteem and the Big-Five (Vecchione et al., 2018); and finally; c) Spanish (Doroszuk et al., 2019).

Regarding the validation made by Doroszuk et al. (2019) for the Spanish version, this was accomplished with Colombian, Chilean and Spanish samples, where the Cronbach’s Alpha (α) reliability coefficients were appropriate, both for admiration (median α = .81) and rivalry (median α = .81), as well as the validity indicators, observed through the differentiated associations patterns with variables such as envy and self-esteem. The instrument in their diverse language adaptions has showed appropriate psychometric properties; however, it is still necessary to carry out research to assess the instrument properties in Venezuelan populations.

For these reasons, the research objective focused on carrying out a first approximation to instrument validation, via studying the psychometric properties of the NARQ in a sample of Venezuelan college students, checking that the instrument has adequate reliability and validity indexes in order to being used in future researches. Also, it is an objective of this research to describe the differences between Venezuelan populations and other Spanish speaking countries.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 159 students from a private college in Caracas, Venezuela. From the total sample, 118 were women (74 %), and the rest were men. The average age of the participants was 20.92 years, with a standard deviation of 2.24 (CV= 10.7 %). Inclusion criteria consisted in being registered in any undergraduate career offered by the college in the then current academic period during the data collection process. The selection of subjects was achieved through a non-probabilistic process, using a snowball sampling (Peña, 2017).

The originally proposed sample size consisted in 180 students, following the recommendations from Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson (2009) of collecting 10 cases per variable in order to carry out a factorial analysis, given that the NARQ is conformed of 18 items. However, this number wasn’t achieved during the data collection; nonetheless, another criteria proposed by Hair et al. (2009) was achieved, that is having a sample of at least 100 cases and a minimum of 5 cases per variable. Participation was completely voluntary; the participants didn’t receive any type of compensation for their participation during the research.

Instruments

Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ)

It is an 18-item questionnaire, with a Likert type response scale, that goes from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). The instrument is divided into two general strategies, which also divide into three subcomponents, conformed of threes items each one. The general strategies are called admiration and rivalry. The first one is composed of: a) grandiosity (e. g. “I am great”), b) striving for uniqueness (e.g., “I show others how special I am”) and c) charmingness (e.g., “I manage to be the center of attention with my outstanding contributions”). In the case of rivalry, this one is composed of: a) devaluation (e.g., “most people won't achieve anything.”), b) striving for supremacy (e.g., “I secretly take pleasure in the failure of my rivals.”), and c) aggressiveness (e.g., “I often get annoyed when I am criticized”) (Back et al., 2013). The version used in this research was the one adapted in Spanish by Doroszuk et al. (2019), which presented adequate Cronbach’s Alpha (α) coefficients, both for admiration (minimum α = .78; maximum α = .84) and for rivalry (minimum α = .81; maximum α = .85).

Big Five Inventory (BFI)

This is a questionnaire composed of 44 self-reported items, with a Likert type response scale that goes from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The first Spanish version was introduced by Benet-Martínez and John (1998), which is the one used in this research. The items are distributed through five scales or factors denominated: extraversion (8 items; e.g., “is outgoing, sociable”), agreeableness (9 items; e.g., “is considerate and kind to almost everyone”), responsibility (9 items: e.g., “is a reliable worker”), neuroticism (8 items: e.g., “gets nervous easily”) and openness (10 items; e.g., “is original, comes up with new ideas”). In regard to the reliability of these five factors, these had presented adequate values for extraversion (α = .79), responsibility (α = .70), neuroticism (α = .74) and openness (α = .76); nonetheless, agreeableness was the scale with the lowest reliability (α = .62) (Domínguez-Lara, Merino-Soto, Zamudio & Guevara-Cordero 2018).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The scale consists in 10 items that refers to general self-esteem. The Spanish version was originally developed by Martín-Albo, Núñez, Navarro and Grijalvo (2007), with posterior modifications by Gómez-Lugo et al. (2016). This last one was used in this research and includes a Likert type answer scale of four points, from a minimum of 1 (totally disagree) to a maximum of 4 (totally agree). The total score of the scale is obtained through the simple sum of all the items, once the scores in the items 2, 6, 8 and 9 are reversed. For these reasons the minimum score is 10, while the maximum score is 40; higher scores represent a higher general self-esteem. Reliability Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for the scale go from .83 to .86 (Gómez-Lugo et al., 2016).

Sociodemographic Information

Sociodemographic characteristics of the students were collected through a self-administered questionnaire, where questions inquiring about age, sex and college career were included.

Procedure

The online version of the questionnaires was constructed via the Google Forms platform. This platform facilitates the elaboration and sharing of online questionnaires through links that can be sent in different ways (e.g., social media, e-mail and instant messaging services); this platform also allows to register the responses from participants, which can later be download as a specific file from the platform itself.

It was included in the questionnaire a welcome message, in a similar form as it would be the case before giving the instructions for a paper and pencil administration; this message included the research objectives, an estimated of the average time for completing the questionnaire, a clarification about the voluntary nature of the participation, and the confidentiality and anonymity of the answers given by the participants. Additionally, it was clarified that the research had only scientific purposes.

The method used for accessing the sample consisted in a snow-ball procedure, in which, via some members of the sample of interest, accessing other members is possible (Peña, 2017). In this case, students from different careers were contacted to complete the survey, and these also shared it with other students from the same university. This process was repeated until the recollection period finalized, seven days after the first survey was sent. Once this term passed, new entries were not allowed in the platform and the final entries were downloaded.

Results

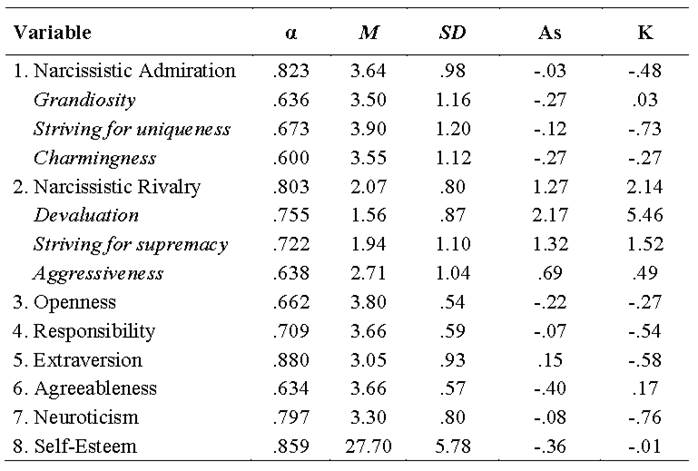

In regard to the NARQ reliability coefficients, the results were similar to the ones found in other Spanish speaking countries. In comparison with the results from Doroszuk et al. (2019) in Chile, Spain and Colombia, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for the complete scales were similar to the Venezuelan sample. Specifically, narcissistic admiration showed an Alpha value of .823 and narcissistic rivalry of .803. These values show that the measurements made with both scales have an adequate reliability, also, these results are similar to the ones reported by Doroszuk et al. (2019). Descriptive and reliability estimates for all instruments are included in Table 1.

Table 1: Reliability coefficients and descriptive statistics for general strategies and subcomponents of NARQ, Big-Five Personality and Self-Esteem

Notes: α = Cronbach’s Alpha; M = arithmetic mean; SD = standard deviation; As = asymmetry; K = kurtosis. All statistics were calculated with a N = 159 for all variables.

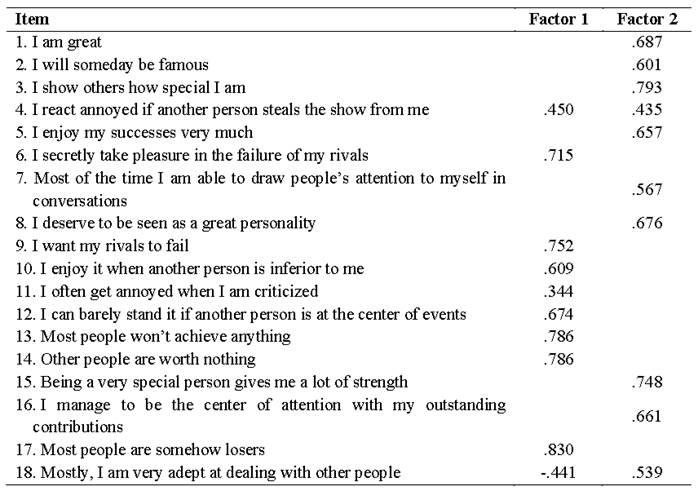

Subsequently, the Factor program (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2013) was used in order to carry out an exploratory factor analysis; specifically, a polychoric correlation matrix was used, given the ordinal level of measurement present in psychological tests with Likert type items (Lloret-Segura, Ferreres-Traver, Hernández-Baeza & Tomás-Marco, 2014). Including the 18 items from the questionnaire, both the KMO (0.858) and the Bartlett’s sphericity test (χ2 (153) = 1751.9; p < .001) pointed out the adequacy of the data to carry out a factorial analysis. The number of factors to be extracted was estimated through a parallel analysis (Horn, 1965), only two factors showed a percentage of explained variance superior to the 95th percentile of the average random explained variance, achieving between these two factors 54.8 % of total variance.

For extracting these factors, the robust unweighted least squares (RULS) method was used, in conjunction with a Robust Promin factor rotation method (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2018), following the recommendations from Lloret-Segura et al. (2014). The resulting factorial structure matched the expected results (see Table 2), given that the items 4, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 17 corresponded to the first factor, narcissistic rivalry; while the remaining items 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 15, 16 and 18 corresponded to the second factor, narcissistic admiration. It’s important to remark that two items showed high factorial loadings with both factors: item 4, from rivalry, and item 18, from admiration. The first one presented positive and very similar factorial loadings, although slightly higher in its proper factor; the second item presented opposed factorial loadings in each factor, although the positive correlation was maintained with its proper factor.

Table 2: Rotated factorial loadings matrix for NARQ

Note: Values equal to or below .30 were omitted.

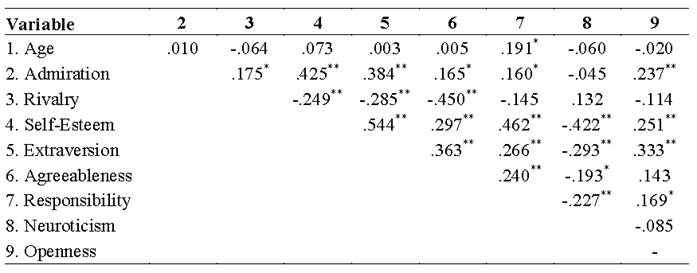

In regard to the correlation between variables, it was found that the rivalry strategy is negatively associated with the extraversion and agreeableness traits and self-esteem. In the case of the admiration strategy, this one showed positive associations with extraversion, openness, affability and responsibility traits and self-esteem. In most cases, these correlations were low, except the association between rivalry and affability (r = -.45), which is moderate (see Table 3).

Table 3: Pearson product-moment correlations for age, NARQ, Self-Esteem and Big-Five Personality

Notes: All correlations were calculated with N = 159. *The correlation is significant at the .05 level (two-tailed). ** The correlation is significant at the .01 level (one-tailed).

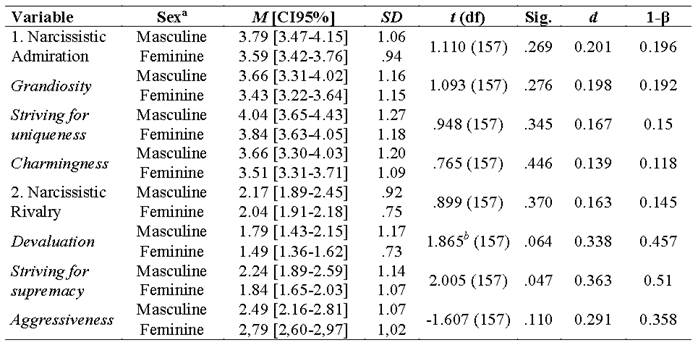

As to the differences generated by sex, there were not statistically significant variations in the general scales of rivalry and admiration; nonetheless, there were differences in the striving for supremacy and devaluation subscales, both which correspond to the general scale of narcissistic rivalry; the first one is significant at the 5 % level and the second one at the 10 % level (see Table 4). For both subscales, the men showed a higher average score, although, this difference size is low. It is important to remark that the statistical power of the test is also low (1-β < 0.8), due to the discrepancy between the number of participants from both sexes, so these results must be interpreted with caution, and expanded upon in balanced samples.

Table 4: Descriptive statistics for general strategies and subcomponents of NARQ, with a sex mean difference test

Notes: M (CI95 %) = arithmetic mean with confidence intervals at 95%; SD = standard deviation; t = independent samples Student’s t test; df= degrees of freedom; Sig. = statistical significance; d = Cohen’s d effect size coefficient; 1-β = statistical power. a Feminine n = 118, Masculine n = 41. b Equality of variance not assumed, by the Levene test.

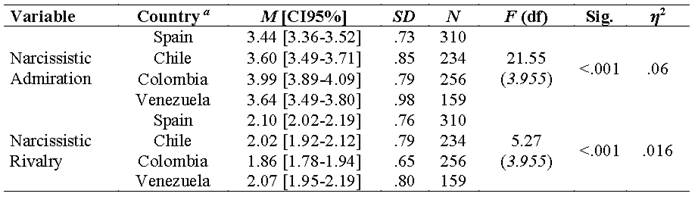

Comparing these results obtained from the Venezuelan sample with the ones from Spain, Chile and Colombia (Doroszuk et al., 2019), the following differences were found: in regard to narcissistic admiration, there were significant differences between these countries, although the effect size was low (η 2 = 0.06). Specifically, the Venezuelan sample showed higher levels of admiration than the Spanish one, but lower than the Colombian sample. In comparison with de Chilean results, there were no differences with the ones obtained in Venezuela (see Table 5).

For narcissistic rivalry, again significant differences were found, although these were low (η 2 = 0.016). Nonetheless, the pattern for this variable was different: the data from the Venezuelan sample only showed differences with the ones from Colombia, given that the Colombians presented lower levels of rivalry. With the Chilean and Spanish samples, there were no significant differences when compared with the Venezuelan one.

Table 5: Descriptive statistics and ANOVA test for narcissistic rivalry and admiration between Spanish, Chilean, Colombian and Venezuelan samples

Notes:M (CI95 %) = arithmetic mean with confidence intervals at 95 % level; SD = standard deviation; N = sample size; F = Fisher’s F test for independent samples; df = degrees of freedom (numerator/denominator); Sig. = two-tailed statistical significance; η 2 = etha-squared effect size coefficient. a The data from Spain, Chile and Colombia were obtained from Doroszuk et al. (2019).

Discussion

The principal research objective was to carry out a first approximation to prove the psychometric adequacy of the Spanish version of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ), developed by Doroszuk et al. (2019), applied to a sample of Venezuelan college students.

In regard to the reliability indexes of the questionnaire, it can be stated that both Rivalry and Admiration scales provide reliable measures, given .80 criteria for Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient; however, the majority of the subscales from the questionnaire didn’t achieve a minimum reliability of .70. These differences could be attributed to the reduced number of items in each subscale, that, when summed, allow for an increased reliability in each general scale (DeVon et al., 2007). Specifically, each subscale is composed of three items, for a combined total of nine items for each scale. Therefore, the results from Rivalry and Admiration scales can be considered reliable; although, the subscales should be analyzed with caution.

The factorial analyses carried out for Admiration and Rivalry scales adjusted to the results reported by Back et al. (2013), albeit the specific techniques used for the exploratory factor analysis were different, in order to adjust them to the recommended practices for this type of variables (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Despite these differences, all analyzed items charged in their respective factors of narcissistic rivalry and admiration.

When delving into the associations between the resulting scores and the variables that, according to the literature, have presented specific correlation patterns, these results can be considered adequate. Specifically, self-esteem has been a variable usually associated with narcissism (Geukes et al., 2017); despite this, there are contradictory results in regard to the direction of the association between these. In this particular research, the results obtained demonstrate that two narcissistic strategies showed opposed correlations with self-esteem: one positive, for narcissistic admiration, and another negative, for narcissistic rivalry, just as stated by Doroszuk et al. (2019) in their research.

The most remarkable difference was observed in the association between the big-five personality traits and the narcissistic strategies, according to the original reports of Back et al. (2013), given the correlation pattern between agreeableness and narcissistic admiration. Originally, these authors found that the relationship between both variables was not significant; however, in this research it was found a positive and significant association. Despite this particular discrepancy, the association patterns were similar to the ones expected, given that narcissistic rivalry correlated with introversion and antagonism, while the narcissistic admiration did it with extroversion and openness to the experience; similar results to the ones obtained by Leckelt et al. (2017).

Another difference found consisted in the role of sex in regard to rivalry and admiration; but it must be taken into consideration that even in the literature theses discrepancies appeared to be present. In their intercultural research, Doroszuk et al. (2019) analyzed the differences between men and women, both in rivalry and in narcissistic admiration. They found that in Chile, Colombia and Spain, men showed higher levels of rivalry than women. But only in Spain this pattern was repeated with admiration, given that men showed higher levels than women. In the other two countries no differences were found.

There are cultural differences in regard to the predominance of men and women in one particular narcissistic strategy, given that usually men show a higher use of the rivalry strategy (Doroszuk et al., 2019). In this Venezuelan sample, this particular pattern was no observed in the general strategies; however, delving in the subcomponents of rivalry, the usual pattern present in other countries was identified. Specifically, men presented a higher devaluation and striving for supremacy (both elements from narcissistic rivalry), when compared to women. It’s important to take into consideration that the test power for sex comparisons was below the ideal levels, so, it’s possible that the reduced sample size may be producing a false negative result (Peña, 2017). Therefore, the Venezuela pattern seems to be similar to the ones found in other countries, once the narcissistic rivalry components are analyzed; however it is necessary to expand on these results recurring to a bigger simple size and balancing the number of group members, achieving in this way an adequate test power, in order to identify possible differences produced by sex.

Conclusion

The Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire is a measurement instrument that is getting more present in the narcissistic personality research. Being a short instrument, it allows to obtain relevant information in a short time and with relative easiness. Its utility lies in the fact that it facilitates the simultaneous measurement of two narcissistic strategies present in the literature and which influences determine the type of relationships with other people and are usually associated with particular social consequences in short and long-terms.

As a sample of its actual relevance, there are multiple language adaptations of this questionnaire. This line of research has even reached Spanish speaking regions, which now have a Spanish adaptation. Despite this, some Latin-American countries do not have a specific study to assess the adequacy of the instrument to their population. This research aimed to contribute the Venezuelan population with a preliminary study that allowed the identification of the adequacy of the NARQ, in regard to reliability and validity standards for scientific and applied research. This objective is considered accomplished, therefore, this can be considered a starting point for the inclusion of the NARQ as an available tool for researchers and practitioners interested in the study of the narcissistic personality, as well as future research that further expand in the study of its psychometric properties in the Venezuelan population.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3ra ed.). Washington: American Psychiatric Association. [ Links ]

Back, M. D. (2018). The narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept. En A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell & J. D. Foster (Eds.), Handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 57-67). Cham: Springer. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_6 [ Links ]

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 1013-1037. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034431 [ Links ]

Benet-Martínez, V. & John, O. P. (1998). Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 729-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.729 [ Links ]

Benson, A. J., Jeschke, J., Jordan, C. H., Bruner, M. W., & Arnocky, S. (2018). Will they stay or will they go? Narcissistic admiration and rivalry predict ingroup affiliation and devaluation. Journal of Personality, 87(4), 871-888. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12441 [ Links ]

DeVon, H. A., Block, M. E., Moyle‐Wright, P., Ernst, D. M., Hayden, S. J., Lazzara, D. J., ... & Kostas‐Polston, E. (2007). A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 39(2), 155-164. [ Links ]

Domínguez-Lara, S., Merino-Soto, C., Zamudio, B., & Guevara-Cordero, C. (2018). Big Five Inventory en universitarios peruanos: Resultados preliminares de su validación. Psykhe, 27(2), 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.27.2.1052 [ Links ]

Doroszuk, M., Kwiatkowska, M. M., Torres‐Marín, J., Navarro‐Carrillo, G., Włodarczyk, A., Blasco‐Belled, A., ... & Rogoza, R. (2019). Construct validation of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire in Spanish‐speaking countries: Assessment of the reliability, structural and external validity and cross‐cultural equivalence. International Journal of Psychology, 55(3), 413-424. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12595 [ Links ]

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 11-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11 [ Links ]

Geukes, K., Nestler, R. H., Dufner, M., Küfner, A. C. P, Egloff, B., Denissen, J. J. A., & Back, M. D. (2017). Puffed-up but shaky selves: State self-esteem level and variability in narcissists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 769-786. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000093 [ Links ]

Gómez-Lugo, M., Espada, J. P., Morales, A., Marchal-Bertrand, L., Soler, F., & Vallejo-Medina, P. (2016). Adaptation, validation, reliability and factorial equivalence of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in Colombian and Spanish population. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 19: e66. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.67 [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data análisis (7ma ed.). Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Hendin, H. M. & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray's Narcism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588-599. doi: https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204 [ Links ]

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in a factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179-185. [ Links ]

Leckelt, M., Wetzel, E., Gerlach, T. M., Ackerman, R. A., Miller, J. D., Chopik, W. J., Penke, L., Geukes, K., Küfner, A. C. P., Hutteman, R., Richter, D., Renner, K.-H., Allroggen, M., Brecheen, C., Campbell, W. K., Grossmann, I., & Back, M. D. (2017). Validation of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire Short Scale (NARQ-S) in convenience and representative samples. Psychological Assessment, 30(1), 86-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000433 [ Links ]

Levy, K. N., Ellison, W. D., & Reynoso, J. S. (2011). A historical review of narcissism and narcissistic personality. En W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.). The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 1-13). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361 [ Links ]

Lorenzo-Serva, U. & Ferrando, P. J. (2018). Robust Promin: un método para la rotación de factores de diagonal ponderada. Liberabit, Revista Peruana de Psicología, 25(1), 99-106. doi: https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2019.v25n1.08 [ Links ]

Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Ferrando, P. J. (2013). FACTOR 9.2: A comprehensive program for fitting exploratory and semiconfirmatory factor analysis and IRT models. Applied Psychological Measurement, 37(6), 497-498. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621613487794 [ Links ]

Martín-Albo, J., Núñez, J. L., Navarro, J. G., & Grijalvo, F. (2007). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and validation in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 458-467. [ Links ]

Peña, G. (2017). Estadística inferencial: Una introducción para las ciencias del comportamiento (2da ed). Caracas: AB ediciones. [ Links ]

Pincus, A. L. & Roche, M. J. (2011). Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. En W. K. Campbell y J. D. Miller (Eds.). The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 31-40). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons . [ Links ]

Raskin, R. & Terry, H. (1988). A principal components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 890-902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890 [ Links ]

Raskin, R. N. & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590-590. doi: https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590 [ Links ]

Rogoza, R., Rogoza, M., & Wyszynska, P. (2016). Polish adaptation of the narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept. Pol. Forum Psychol. 21, 410-431. doi: https://doi.org/10.14656/PFP20160306 [ Links ]

Rogoza, R., Zemojtel-Piotrowska, M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Measure of narcissism: From classical applications to modern approaches. Studia Psychologica: Teoria et Praxis, 18(1), 27-48. doi: https://doi.org/10.21697/sp.2018.18.1.02 [ Links ]

Tyler, I. (2007). From “the me decade” to “the me millennium”: The cultural history of narcissism. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(3), 343-363. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877907080148 [ Links ]

Vecchione, M., Dentale, F., Graziano, M., Dufner, M., Wetzel, E., Leckelt, M., & Back, M. D. (2018). An Italian validation of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ): Further evidence for a two-dimensional model of grandiose narcissism. BPA-Applied Psychology Bulletin, 66(281), 29-37. [ Links ]

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590-597. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590 [ Links ]

Wurst, S. N., Gerlach, T. M., Dufner, M., Rauthmann, J. F., Grosz, M. P., Küfner, A. C. P., Denissen, J. J. A., & Back, M. D. (2017). Narcissism and romantic relationships: The differential impact of narcissistic admiration and rivalry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(2), 280-306. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000113 [ Links ]

Correspondence: Daniel Chaustre Jota, Centro de Investigación y Evaluación Institucional (CIEI) en la Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB), Venezuela. E-mail: dchaustr@ucab.edu.ve

How to cite: Chaustre Jota, D. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ) in college students from Venezuela. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(2), e-2484. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2484

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. D. C. J. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e.

Received: March 04, 2021; Accepted: August 31, 2021

texto em

texto em